All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Regimen Switching After Initial Haart By Race in a Military Cohort

Abstract

Background:

Prior studies have suggested that HAART switching may vary by ethnicity, but these associations may be confounded by socioeconomic differences between ethnic groups. Utilizing the U.S. military healthcare system, which minimizes many socioeconomic confounders, we analyzed whether HAART switching varies by race/ethnicity.

Methods:

HAART-naïve participants in the U.S. Military HIV Natural History Study who initiated HAART between 1996-2012 and had at least 12-months of follow-up were assessed for factors associated with HAART regimen change (e.g. NNRTI to PI) within one year of initiation. Multiple logistic regression was used to compare those who switched versus those who did not switch regimens.

Results:

2457 participants were evaluated; 91.4% male, 42.3% Caucasian, 42.8% African-American, and 9% Hispanic. In a multivariate analysis, African-Americans had lower odds (OR 0.76, 95% CI 0.65, 0.98) while Hispanics had no significant difference with respect to HAART switching compared to Caucasians; however, Other race was noted to have higher odds (OR 1.77, 95% CI 1.11, 2.83). Additional significantly associated factors included CD4 <200 cells/uL at HAART initiation, higher viral load, prior ARV use, and history of depression.

Conclusion:

In this cohort with open access to healthcare, African-American and Hispanic races were not associated with increased odds of switching HAART regimen at 12 months, but Other race was. The lack of association between race/ethnicity and regimen change suggest that associations previously demonstrated in the literature may be due to socioeconomic or other confounders which are minimized in the military setting.

1. BACKGROUND

Since its introduction in the mid-1990s, highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) for the treatment of HIV infection has proved efficacious in reducing morbidity and mortality and suppressing viral replication [1, 2]. However, virologic or immunological failure, drug toxicities, drug interactions, and problems with adherence, often lead to discontinuing, interrupting, or switching HAART regimens. These changes, particularly early modification of initial HAART medications within the first year of therapy, have been associated with poor clinical outcomes [3]. Also, exposure to the finite number of treatment medications available can diminish the effectiveness of related drugs in future therapeutic regimens [4]. Both the International AIDS Society-USA Panel [5] and the Department of Health and Human Services [6] have cautioned against prematurely switching antiretroviral regimens because of limitations placed on future treatment alternatives due to potential or actual development of viral resistance.

The reasons for switching HAART medication regimens are multifactorial and include failure of current therapy, drug toxicity and drug interactions, as well as non-compliance [7]. Studies have shown that patients with lower mean CD4+ count and higher HIV RNA levels are more likely to switch HAART [4, 8]. Marital status as well as time from HIV diagnosis to HAART initiation has also been associated with HAART treatment modification [9, 10].

Many individuals infected with HIV and treated with HAART are from U.S. minority race/ethnicity groups [1] and although reports have suggested that race/ethnicity is a risk factor for changing/switching the HAART regimen, few studies have investigated regimen switching in minority populations; however, African-American race has been associated with switching, interrupting [2], and discontinuing HAART [7, 11-14]. The effect size of African American race on discontinuation (HR 1.26) was similar to that of higher pill burden in one report [7] and the adjusted odds of interruption for African Americans (OR 1.77) was similar to the effect of depression in another [12]. Hispanics have been less well studied, but one report that grouped Hispanics with African Americans and Others showed a 2-fold hazard for discontinuation of HAART [13]. Additionally, studies have shown possible differences between races/ethnicities in adherence and ability to manage drug toxicities [15-17]. In these studies, potential confounding due to the association of race/ethnicity with social factors, such as and access to healthcare and medications, has been challenging to address.

The U.S. Military HIV Natural History Study cohort minimizes many of the confounding social factors and so, we sought to address this question. If race/ethnicity is not itself a risk factor for early HAART switching, which is associated with poor clinical outcomes [3], then clinical and public health efforts to improve HAART outcomes can be focused toward access to healthcare and medications, as well as other related factors. The U.S. Military HIV Natural History Study (NHS) provides the ability to evaluate associations between race/ethnicity and clinical outcomes without many of the socioeconomic confounders in other cohort studies. Within the military healthcare system there is free cost and equal access to healthcare and medications, and military members have steady income and a minimum of a high school education or equivalent. Previous studies in the NHS have shown that despite this, African Americans were less likely to achieve viral suppression after initiating HAART [18-19]. However, clinical outcomes after HAART initiation were similar among races/ethnicities in other studies in our cohort [20, 21], although risk factors for adverse outcomes may differ by race/ethnicity.

We sought to test the hypothesis that in a U.S. military cohort, non-Caucasian race/ethnicity HIV-positive patients are no more likely to switch initial HAART regimens within a one-year period of time than Caucasian subjects while also exploring other factors related to HAART switching.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study Population

The U.S. Military HIV Natural History Study (NHS) is a prospective cohort study consisting of HIV+ Department of Defense (DoD) beneficiaries including active duty military personnel, retirees and dependents [20]. Since 2000, active duty members undergo routine biannual HIV screening, therefore disease is frequently diagnosed early in its progression. Active duty HIV+ individuals seen for care at one of the six NHS sites are offered participation in the study. NHS subjects have study visits approximately every 6 months where data including demographics, medical history, medications, and lab tests are collected. All participants provide signed informed consent and the NHS protocol has been approved by the central institutional review board (IRB) at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences (USU) for all participating sites.

2.2. Study Design

HAART naïve subjects from the NHS initiating HAART from 1996 through 2012 were included for analysis. Baseline was defined as time of HAART initiation. As the NHS is an observational study, therapy was initiated by individual providers based on treatment guidelines and patient preferences. Initial combination regimens for the treatment-naïve were generally prescribed in accordance with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents [6].

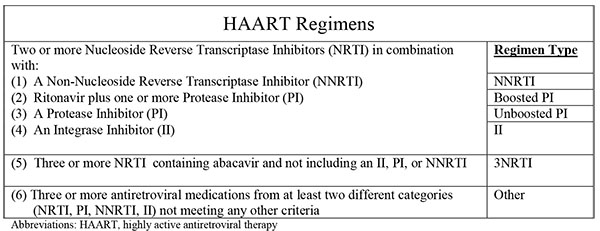

For this study, HAART regimen is defined by the schematic in Fig. (1). Any regimen not meeting the definitions for HAART was deemed a ‘non-HAART’ regimen. A ‘switch’ was defined as a change in prescribed HAART regimen from one of the six defined classes (referred to hereafter as ‘regimens’) to any another HAART or non-HAART regimen within the first year of HAART initiation. Because early modification of initial HAART medications have been associated with poor clinical outcome in HIV patients, we chose to focus on this question and limited the analysis to the first year after HAART initiation. For individuals who switched multiple times during the first year of therapy, the first new regimen was deemed the ‘switched to’ regimen. Discontinuations were also noted. Analyses were stratified by year of HAART initiation grouped into three periods (1996-2001, 2002-2007, 2008-2012), roughly corresponding to eras of changes in first-line HAART regimens and/or DHHS guidelines.

Factors analyzed for association with regimen switching included: demographics, baseline HIV related factors, prevalent chronic medical conditions at HAART initiation including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), coronary artery disease, malignancy other than basal cell carcinoma, active tuberculosis, anxiety disorder, major depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, and prior suicide attempt, as well as nine serum markers measured at baseline (ALT, AST, creatinine, hemoglobin, total bilirubin, HDL, LDL, triglycerides, and glucose). Data regarding reasons for switching regimens were not captured in the database, so were not available for analysis. Race was captured as single, mutually exclusive categories; because of small numbers, those self reporting race as Asian/Pacific Islander, Native American/Alaskan Native, or Other (specify) were grouped in a single category, ‘Other race.’

2.3. Statistical Methods

Student t tests and chi-square tests were used to compare differences in demographic characteristics and HIV related measures between HAART switching and non-switching groups. The odds of switching HAART between ethnicity groups were calculated using logistic regression with 95% confidence intervals. Univariate models were used to test associations of demographic characteristics, HIV related measures, and HAART initiation era with switching. All univariate factors were initially included in the multivariate models and removed in a backward stepwise fashion based on an alpha of 0.05. All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4 (Cary, NC).

3. RESULTS

2457 subjects met the inclusion criteria. The population studied was predominantly male (91%) with a median age of 34 years (Table 1). 42% of the cohort were Caucasian, 43% African-American, 9% Hispanic and 6% were Other race. 65% of the subjects initiated HAART during 1996-2001, 19% during 2002-2007 and 15% during 2008-2012. Overall, the most common regimen initiated was unboosted PI (51%) followed by NNRTI (34%) and boosted PI (7%). At the time of HAART initiation 84% were active duty.

There were significant differences in HIV viral load, but not CD4 count at HAART initiation between race/ethnicity groups (Table 1); however, the largest proportion of subjects in each group had viral loads greater than 10,000 log10 copies/ml and CD4 counts above 350 cells/ml. Those in the Hispanic and other groups had a significantly shorter time between HIV diagnosis and HAART initiation and significantly more individuals in these groups started HAART in the 2008-2012 era than the 1996-2001 era compared to Caucasians and African Americans (Table 1).

Caucasians were significantly more likely to have malignancies other than basal cell carcinoma, and coronary artery disease at HAART initiation. Major depression was diagnosed in 24.2% and anxiety disorder in 8.8% of the total population, but each were significantly lower in African-Americans compared with Caucasians, Hispanic or Other racial groups. There were several baseline lab values that were statistically different between ethnicities (AST, total bilirubin, HDL, LDL, triglycerides, creatinine and hemoglobin), but these were not felt to be clinically significant. (Table 1 and Supplementary Table S1).

| TOTAL COHORT N(%) or Median(IQR) N=2457 |

CAUCASIAN N(%) or Median(IQR) N=1040 |

AFRICAN-AMERICAN N(%) or Median (IQR) N=1052 |

HISPANIC N(%) or Median(IQR) N=231 |

OTHER N(%) or Median(IQR) N=134 |

P-VALUE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prior Medical Illnesses | ||||||

| Cerebrovascular Disease | 15 (0.6%) | 8 (0.8%) | 4 (0.4%) | 2 (0.9%) | 1 (0.7%) | 0.6504 |

| Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease | 27 (1.1%) | 18 (1.7%) | 6 (0.6%) | 1 (0.4%) | 2 (1.5%) | 0.0536 |

| Chronic Viral Hepatitis Disease | 274 (11.2%) | 104 (10.0%) | 134 (12.7%) | 24 (10.4%) | 12 (9.0%) | 0.1831 |

| Cirrhosis | 25 (1.0%) | 13 (1.3%) | 7 (0.7%) | 4 (1.7%) | 1 (0.7%) | 0.3734 |

| Coronary Artery Disease | 71 (2.9%) | 46 (4.4%) | 16 (1.5%) | 7 (3.0%) | 2 (1.5%) | 0.0008 |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 201 (8.2%) | 82 (7.9%) | 92 (8.7%) | 19 (8.2%) | 8 (6.0%) | 0.6962 |

| Malignancy other than Basal Cell Carcinoma | 273 (11.1%) | 171 (16.4%) | 81 (7.7%) | 12 (5.2%) | 9 (6.7%) | <.0001 |

| Tuberculosis other than latent infection | 37 (1.5%) | 8 (0.8%) | 19 (1.8%) | 6 (2.6%) | 4 (3.0%) | 0.0406 |

| Prior Mental Health Illnesses | ||||||

| Anxiety Disorder | 215 (8.8%) | 128 (12.3%) | 50 (4.8%) | 24 (10.4%) | 13 (9.7%) | <.0001 |

| Bipolar Disorder | 48 (2.0%) | 22 (2.1%) | 21 (2.0%) | 3 (1.3%) | 2 (1.5%) | 0.8451 |

| Major Depression | 594 (24.2%) | 274 (26.3%) | 225 (21.4%) | 56 (24.2%) | 39 (29.1%) | 0.0305 |

| Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder | 3 (0.1%) | 1 (0.1%) | 1 (0.4%) | 1 (0.7%) | 0.0588 | |

| Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder | 37 (1.5%) | 13 (1.3%) | 13 (1.2%) | 6 (2.6%) | 5 (3.7%) | 0.0627 |

| Prior Suicide Attempt | 23 (0.9%) | 7 (0.7%) | 5 (0.5%) | 7 (3.0%) | 4 (3.0%) | 0.0002 |

| Schizophrenia | 5 (0.2%) | 2 (0.2%) | 2 (0.2%) | 1 (0.7%) | 0.488 | |

| Substance Abuse | 283 (11.5%) | 135 (13.0%) | 104 (9.9%) | 31 (13.4%) | 13 (9.7%) | 0.1029 |

| Serum Levels at Initiation | ||||||

| ALT(U/L) | 32 (25) | 32 (25) | 32 (23) | 35 (28) | 32 (23) | 0.0001 |

| AST(U/L) | 30 (16) | 28 (13) | 32 (18) | 31 (18) | 29 (14) | <.0001 |

| Total Bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.6 (0.4) | 0.6 (0.4) | 0.6 (0.3) | 0.6 (0.4) | 0.6 (0.4) | <.0001 |

| HDL (mg/dL) | 39 (15) | 37 (14) | 43 (14) | 37 (15) | 37 (12) | 0.0389 |

| LDL (mg/dL) | 100 (39) | 99 (41) | 105 (41) | 97 (32) | 100 (44) | <.0001 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 114 (98) | 135 (119) | 98 (75) | 132 (114) | 110.5 (68) | 0.4518 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 87 (17) | 87 (18) | 86 (16) | 87 (15) | 87 (13) | <.0001 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.0 (0.2) | 1.0 (0.2) | 1.0 (0.3) | 0.9 (0.3) | 0.9 (0.3) | <.0001 |

| Hemoglobin(g/dL) | 14.3 (1.9) | 14.6 (1.8) | 13.9 (1.8) | 14.7 (1.7) | 14.8 (1.8) | 0.0001 |

3.1. Trends in Initial HAART Regimens and Switching

Of the 2457 subjects, 24.8% switched HAART regimens within the first year of initiation, 23.1% continuing on another regimen and 1.8% discontinuing therapy. Reflecting the regimens used at the time, most subjects initiating HAART from 1996-2001 started unboosted PI regimens (n=1,215, most were indinavir or nelfinavir) followed by NNRTI (n= 245) and had a 30.2% and 22.5% switch rate in the first year, respectively. For those beginning HAART during the periods 2002-2007 and 2008-2012, the most common initial regimens were NNRTI, however the highest switching rates occurred among those starting on unboosted PI regimens and other non-standard regimens. 29% of subjects initiating HAART between 1996-2001 switched, compared to 19% between 2008-2012 (Table 2).

| Class | 1996-2001 | 2002-2007 | 2008-2012 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % of regimen switched |

#switched/ #initiated (%) |

% of regimen switched |

#switched/ #initiated (%) |

% of regimen switched |

#switched/ #initiated (%) |

|

| NNRTI | 11.80% | 55/245 (22.45%) | 49.45% | 45/330 (13.64%) | 50.94% | 27/262 (10.31%) |

| Boosted PI | 2.58% | 12/25 (48.00%) | 19.78% | 18/80 (22.50%) | 35.85% | 19/64 (29.69%) |

| Unboosted PI | 78.76% | 367/1215 (30.21%) | 10.99% | 10/24 (41.67%) | 7.55% | 4/8 (50.00%) |

| Integrase Inhibitor | 0.00% | 0/0 | 0.00% | 0/0 | 3.77% | 2/33 (6.06%) |

| 3NRTI | 1.29% | 6/37 (16.22%) | 12.09% | 11/30 (36.67%) | 0.00% | 0/0 |

| Other | 5.58% | 26/86 (30.23%) | 6.59% | 6/11 (54.55%) | 1.89% | 1/4 (20.00%) |

| Non-HAART | 0.00% | 0/0 | 1.10% | 1/2 (50.00%) | 0.00% | 0/1 (0.00%) |

3.2. Factors Associated with HAART Switching

Of the total study population, 26.1% of Caucasians, 22% of African Americans, 27.2% of Hispanic and 33.6% of the Other race group switched HAART regimens within one year of HAART initiation. In multivariate analyses, the odds of switching HAART regimens at one year were significantly lower for African-American race (aOR 0.76, 95% CI 0.65, 0.98) and significantly higher for Other race (aOR 1.77, 95% CI 1.11, 2.83) compared with Caucasian race. There was no difference in odds of switching between Hispanic and Caucasian race (aOR 1.22, 95% CI 0.84, 1.77). Additionally, dependent status had a higher odds ratio of regimen switch compared with active duty (OR 1.66, 95% CI 1.15, 2.41). Other demographics such as gender, marital status and rank were not significantly associated with regimen switching.

HIV related factors including low CD4, high viral load, and earlier HAART initiation era were associated with increased odds of switching (Table 3). Initiating HAART at CD4 <200 cells/ml compared to >350 cells/ml was associated with a two-fold higher risk of switching HAART in multivariate analysis (aOR 1.94, 95% CI 1.43, 2.63). Similarly viral load >1,000 copies/ml significantly increased the odds of switching HAART compared to <400 copies/ml (aOR 1.82, 95% CI 1.13, 2.94 for viral load 1000-10,000 copies/mL and aOR 1.67, 95% CI 1.07, 2.6 for viral load >10,000 copies/mL). ARV use prior to HAART initiation was associated with increased odds of switching HAART in both univariate and multivariate analyses (aOR 2.06, 95% CI 1.63, 2.62) (Table 3).

|

REGIMEN SWITCH N=610 (24.8%) N(%) or Median(IQR) |

NO REGIMEN SWITCH N=1847 (75.2%) N(%) or Median(IQR) |

UNIVARIATE ODDS RATIO (95% CI) |

P- VALUE |

MULTIVARIATE ODDS RATIO (95% CI) |

P- VALUE |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||||

| Age(years) | 34 (10.0) | 34 (11.0) | 1.00 (0.99,1.01) | 0.444 | 0.98 (0.96,0.99) | 0.0006 |

| Gender(%Female) | 64 (10.5%) | 158 (8.1%) | 1.35 (0.99,1.83) | 0.0594 | ||

| Marital Status(%Married) |

156 (30.6%) | 182 (29.8%) | 0.93 (0.76,1.13) | 0.4685 | ||

| Race/Ethnicity | 0.0012 | |||||

| Caucasian | 271 (44.4%) | 769 (41.6%) | referent | referent | ||

| African-American | 231 (37.9%) | 821 (44.5%) | 0.80 (0.65,0.98) | 0.0283 | 0.76 (0.6,0.98) | 0.0332 |

| Hispanic | 63 (10.3%) | 168 (9.1%) | 1.06 (0.77,1.47) | 0.7043 | 1.22 (0.84,1.77) | 0.3018 |

| Other | 45 (7.4%) | 89 (4.8%) | 1.44 (0.98,2.11) | 0.0654 | 1.77 (1.11,2.83) | 0.0165 |

| Rank Status | ||||||

| Officer/Warrant | 53 (8.7%) | 185 (10.0%) | 0.92 (0.66,1.26) | 0.5873 | ||

| Enlisted | 468 (76.7%) | 1494 (80.9%) | referent | |||

| Duty Status | ||||||

| Active | 495 (81.1%) | 1573 (85.2%) | referent | |||

| Retired | 29 (4.8%) | 88 (4.8%) | 1.05 (0.68,1.61) | 0.834 | ||

| Dependent | 46 (7.5%) | 88 (4.8%) | 1.66 (1.15,2.41) | 0.0072 | ||

| Other | 40 (6.6%) | 98 (5.3%) | 1.3 (0.89,1.9) | 0.1813 | ||

| Site | ||||||

| NMCP | 37 (6.1%) | 140 (7.6%) | 0.76 (0.52,1.12) | 0.1711 | ||

| NMCSD | 92 (15.1%) | 264 (14.3%) | 1.01 (0.77,1.32) | 0.9607 | ||

| SAMMC | 183 (30.0%) | 553 (29.9%) | 0.96 (0.77,1.18) | 0.6812 | ||

| TAMC | 9 (1.5%) | 55 (3.0%) | 0.47 (0.23,0.97) | 0.0407 | ||

| WRNMMC | 289 (47.4%) | 835 (45.2%) | referent | |||

| HIV Related | ||||||

| HIV Diagnosis to HAART initiation (months) | 52 (98.2) | 29 (75.6) | 1.003 (1.001,1.005) | <.0001 | ||

| Viral load at HAART Initiation (log copies/ml) | 0.0271 | |||||

| <400 | 34 (5.6%) | 188 (10.2%) | referent | referent | ||

| 400-<1000 | 47 (7.7%) | 189 (10.2%) | 1.38 (0.85,2.23) | 0.1983 | 1.06 (0.61,1.86) | 0.8287 |

| 1000-<10000 | 131 (21.5%) | 343 (18.6%) | 2.11 (1.39,3.21) | 0.0004 | 1.82 (1.13,2.94) | 0.0138 |

| >=10000 | 381 (62.5%) | 1047 (56.7%) | 2.01 (1.37,2.95) | 0.0004 | 1.67 (1.07,2.6) | 0.0241 |

| Missing | 17 (2.8%) | 80 (4.3%) | ||||

| CD4 Cell Count at HAART initiation (cells/ml) | 0.0001 | |||||

| <200 | 203 (33.3%) | 306 (16.6%) | 2.65 (2.1,3.34) | <.0001 | 1.94 (1.43,2.63) | <.0001 |

| 200-<350 | 165 (27.0%) | 567 (30.7%) | 1.16 (0.93,1.46) | 0.1964 | 1.14 (0.88,1.49) | 0.3289 |

| >=350 | 216 (35.4%) | 863 (46.7%) | referent | referent | ||

| Missing | 26 (4.3%) | 111 (6.0%) | ||||

| ARV Prior to HAART (%) | 365 (59.8%) | 748 (40.5%) | 2.19 (1.82,2.64) | <.0001 | 2.06 (1.63,2.62) | <.0001 |

| Period of HAART Initiation | ||||||

| 1996-2001 | 466 (76.4%) | 1142 (61.8%) | 2.46 (1.8,3.35) | <.0001 | ||

| 2002-2007 | 91 (14.9%) | 386 (20.9%) | 1.42 (0.98,2.05) | 0.0636 | ||

| 2008-2012 | 53 (8.7%) | 319 (17.3%) | referent | |||

| Comorbidities | ||||||

| Malignancy other than Basal Cell Carcinoma | 100 (16.4%) | 173 (9.4%) | 1.90 (1.46,2.47) | <.0001 | ||

| Diabetes Mellitus | 68 (11.1%) | 133 (7.2%) | 1.62 (1.19,2.20) | 0.0022 | ||

| Anxiety Disorder | 71 (11.6%) | 144 (7.8%) | 1.56 (1.15,2.10) | 0.0038 | ||

| Major Depression | 196 (32.1%) | 398 (21.5%) | 1.72 (1.41,2.11) | <.0001 | 1.48 (1.15,1.9) | 0.0023 |

| Substance Abuse | 85 (13.9%) | 198 (10.7%) | 1.35 (1.03,1.77) | 0.0315 | ||

| Serum Levels at HAART Initiation | ||||||

| ALT(U/L) | 34 (26.0) | 32 (23.0) | 1.00 (1.00,1.00) | 0.1366 | ||

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | 0.79 (0.50,1.24) | 0.3023 | ||

| Hemoglobin(g/dL) | 14 (2.1) | 14 (1.7) | 0.85 (0.79,0.91) | <.0001 | 0.9 (0.83,0.97) | 0.0048 |

Prevalent comorbidities including diabetes, malignancies, anxiety disorder, bipolar disorder, major depression, and prior suicide attempt were all independently associated with increased odds of HAART switching. In multivariate analyses, major depression remained significantly associated with switching (aOR 1.48, 95% CI 1.15, 1.9) (Table S2).

|

SWITCH REGIMEN N=610 (24.8%) N(%) or Median(IQR) |

NO SWITCH REGIMEN N=1847 (75.2%) N(%) or Median(IQR) |

UNIVARIATE ODDS RATIO (95% CI) |

P- VALUE |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medical Illnesses | ||||

| Cerebrovascular Disease | 6 (1.0%) | 9 (0.5%) | 2.03 (0.72,5.73) | 0.1806 |

| Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease | 11 (1.8%) | 16 (0.9%) | 2.10 (0.97,4.56) | 0.0594 |

| Chronic Viral Hepatitis Disease | 80 (13.1%) | 194 (10.5%) | 1.29 (0.97,1.70) | 0.0762 |

| Cirrhosis | 5 (0.8%) | 20 (1.1%) | 0.76 (0.28,2.02) | 0.5758 |

| Coronary Artery Disease | 22 (3.6%) | 49 (2.7%) | 1.37 (0.82,2.29) | 0.2245 |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 68 (11.1%) | 133 (7.2%) | 1.62 (1.19,2.20) | 0.0022 |

| Malignancy other than Basal Cell Carcinoma | 100 (16.4%) | 173 (9.4%) | 1.90 (1.46,2.47) | <.0001 |

| Tuberculosis other than latent infection | 12 (2.0%) | 25 (1.4%) | 1.46 (0.73,2.93) | 0.2831 |

| Mental Health Illnesses | ||||

| Anxiety Disorder | 71 (11.6%) | 144 (7.8%) | 1.56 (1.15,2.10) | 0.0038 |

| Bipolar Disorder | 21 (3.4%) | 27 (1.5%) | 2.41 (1.35,4.29) | 0.0029 |

| Major Depression | 196 (32.1%) | 398 (21.5%) | 1.72 (1.41,2.11) | <.0001 |

| Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder | 11 (1.8%) | 26 (1.4%) | 1.29 (0.63,2.62) | 0.4877 |

| Prior Suicide Attempt | 10 (1.6%) | 13 (0.7%) | 2.35 (1.03,5.39) | 0.0431 |

| Substance Abuse | 85 (13.9%) | 198 (10.7%) | 1.35 (1.03,1.77) | 0.0315 |

| Serum Levels at Initiation | ||||

| ALT(U/L) | 33.5 (26) | 32 (23) | 1.00 (1.00,1.00) | 0.1366 |

| AST(U/L) | 31 (17) | 29 (15) | 1.00 (1.00,1.00) | 0.0945 |

| Total Bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.6 (0.35) | 0.6 (0.4) | 1.25 (1.03,1.51) | 0.0207 |

| HDL (mg/dL) | 37 (15) | 39 (15) | 0.97 (0.96,0.99) | 0.0007 |

| LDL (mg/dL) | 97 (38) | 101 (41) | 1.00 (0.99,1.00) | 0.1451 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 133 (122) | 110 (92) | 1.00 (1.00,1.00) | 0.0927 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 87 (20) | 87 (16) | 1.00 (1.00,1.01) | 0.4271 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | 0.79 (0.50,1.24) | 0.3023 |

| Hemoglobin(g/dL) | 14 (2.1) | 14.4 (1.7) | 0.85 (0.79,0.91) | <.0001 |

When comparing factors significantly associated with regimen switching by race just among patients that had a regimen switch, Caucasians were slightly older (p=<0.001) and had more prior ARV use (p=0.05). CD4 count, HIV viral load, and history of depression were not statistically different (Table S3).

|

TOTAL COHORT N(%) or Median(IQR) N=610 |

CAUCASIAN N(%) or Median(IQR) N=271 |

AFRICAN-AMERICAN N(%) or Median (IQR) N=231 |

HISPANIC N(%) or Median(IQR) N=63 |

OTHER N(%) or Median(IQR) N=45 |

P-VALUE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age(years) | 34 (10.0) | 35 (10.0) | 33 (12.0) | 32 (12.0) | 33 (11.0) | <0.0001 |

| Viral load at HAART Initiation (log copies/ml) |

0.8210 | |||||

| <400 | 34 (5.6%) | 19 (7.01%) | 12 (5.2%) | 2 (3.2%) | 1 (2.2%) | |

| 400-<1000 | 47 (7.7%) | 24 (8.9%) | 16 (6.9%) | 4 (6.4%) | 3 (6.7%) | |

| 1000-<10000 | 131 (21.5%) | 63 (23.3%) | 44 (19.1%) | 13 (20.3%) | 11 (24.4%) | |

| >=10000 | 381 (62.5%) | 156 (57.6%) | 154 (66.7%) | 43 (68.3%) | 28 (62.2%) | |

| Missing | 17 (2.8%) | 9 (3.3%) | 5 (2.2%) | 1 (1.6%) | 2 (4.4%) | |

| CD4 Cell Count at HAART initiation (cells/ml) |

0.3764 | |||||

| <200 | 203 (33.3%) | 89 (32.8%) | 78 (33.8%) | 24 (38.1%) | 12 (26.7%) | |

| 200-<350 | 165 (27.1%) | 70 (25.8%) | 71 (30.7%) | 13 (20.6%) | 11 (24.4%) | |

| >=350 | 216 (35.4%) | 100 (36.9%) | 71 (30.7%) | 26 (41.3%) | 19 (42.2%) | |

| Missing | 26 (4.3%) | 12 (4.4%) | 11 (4.8%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (6.7%) | |

| ARV Prior to HAART (%) | 365 (59.8%) | 172 (63.5%) | 139 (60.2%) | 35 (55.6%) | 19 (42.2%) | 0.0506 |

| Major Depression | 196 (32.1%) | 87 (32.1%) | 73 (31.6%) | 20 (31.8%) | 16 (35.6%) | 0.9645 |

| Hemoglobin(g/dL) | 14 (2.1) | 14.4 (2.4) | 13.6 (1.9) | 14.7 (1.7) | 14.8 (1.8) | <0.0001 |

4. DISCUSSION

This study showed lower odds of switching HAART medication regimens in African-Americans and no greater odds in Hispanics compared to Caucasians at one year after initiating HAART, however other races were more likely to switch, but constituted a small proportion of studied subjects. It is important to characterize the frequencies of switching specific HAART regimens as this provides an estimation of the rate at which the regimens may be failing or intolerable. We used the U.S. Military HIV Natural History Study to evaluate the frequency and type of HAART regimen switching over a 15-year period focusing on differences among race/ethnicity groups in a setting with minimal socioeconomic confounding. The proportion of subjects who switched regimens in this study is lower than that generally reported in the literature possibly related to fewer socioeconomic and healthcare availability factors in the military setting. However, elements known to be associated with HAART medication (HIV viral load and CD4 count) demonstrated statistically significant relationships in this study to odds of switching at 12 months [4, 22].

While studies have described frequencies [8, 23, 24], probabilities [25, 26] and risk [27] of discontinuing or switching HAART regimens as well as proportions of subjects changing [28], interrupting [29], or stopping/discontinuing [30] medications, few studies have documented trends in discontinuing or switching HAART medications in minority populations. Data from the Women’s Interagency HIV Study [11] showed that compared to those who did not switch from their initial regimen, those who did switch were significantly more likely to be African American (65% vs 50%). In studies that did not specify HAART-naïve subjects, Li et al. [12] found that Black race was an independent predictor for short interruption of HAART for </= 7 days (OR 2.42, 95% CI 1.23, 4.74); also, Yuan et al. [7]described that Black race was predictive of discontinuation (RR=1.28, 95% CI 1.13, 1.45) while Robison et al. [14] illustrated Black race was associated with discontinuation (OR 1.68, 95% CI 1.80, 2.60) for virologic failure/ non-adherence. In our study, there was a lower odds of switching HAART regimens in African-American compared to Caucasian race in both univariate and multivariate analyses. This may be explained by equal access and lower barriers to medical care seen in the military healthcare system.

There have been few studies that have further stratified other races and thus few data are available on HAART switching among Hispanic populations. In our study they were noted to have no higher rate of discontinuation when compared with Caucasians. Finally, there were increased odds of switching HAART among the Other race group compared to Caucasians even in multivariate analyses that may be related to the relatively small numbers in this group. All of the above differences were noted to be despite similar breakdown by CD4 and viral load and an increased proportion of the group starting HAART in later periods.

In this NHS cohort, while 24.8% of the study subjects switched regimens, the vast majority of those patients switched in the earliest time period of 1996-2001 (76.4%). This finding makes sense as most of the subjects in our cohort initiated HAART in the earliest period, marked by higher pill burden and regimen toxicity, as well as lower potency. Mocroft et al. [28] found the incidence of any discontinuation of HAART was significantly lower after 1999 compared to before [incidence rate ratio 0.43, 95% CI 0.35, 0.53]. Also, Cicconi et al. [26] illustrated that patients who started HAART during a 'recent' period of 2003-2007 were less likely to change their initial regimen because of intolerance/toxicity [adjusted relative hazard 0.67, 95% CI 0.51, 0.89] compared to an ‘early’ period (1997-1999). Similarly, in our study, HAART initiation during the later period 2008-2012 had a much lower rate of regimen switching of 14.2%, suggesting the use of those regimens currently recommended by the DHHS may decrease the risk of switching.

This study demonstrated clear, significant associations between HIV viral load, CD4 count, as well as having depression, and odds of switching HAART regimens. These associations are reassuring as indicators of internal study validity. The association with depression is particularly interesting given associations previously described between depression and HAART uptake and adherence. Depressed patients with HIV infection are an important group receiving HAART prescriptions and this association may suggest this population would benefit from additional provider/clinic-based interventions, including enhanced adherence counseling, support, or closer monitoring after HAART initiation. Furthermore, the significant association between higher viral load at initiation and switching in multivariate analysis is consistent with prior studies demonstrating higher likelihood of discontinuing, interrupting, and modifying HAART regimens compared to lower values [12, 31, 32]. Prior antiretroviral use was associated with a two-fold increased risk of regimen switching (adjusted OR 2.06, 95% CI 1.63, 2.62)) suggesting possible HIV resistance. Van Roon [23] has described non-naiveté for ART as a determinant for discontinuation of initial HAART and Mocroft [31] showed that previously-treatment naïve patients are less likely to modify HAART. This finding also suggests that this population might benefit from closer monitoring after HAART initiation.

There are some study limitations. As the cohort is predominantly male, findings may not be fully reflective of HAART switching among women; additionally, while the cohort is derived from geographically and racially/ethnically diverse individuals from the U.S. population and is likely representative of those with open access to healthcare and medications, unmeasured differences may exist that could limit generalizability, especially to those who are socioeconomically disadvantaged. This was a retrospective analysis covering a broad timeframe and involved multiple sites (sites were not significantly associated with switching in the multivariate analysis) among which practice patterns may have varied. Additionally this was a cross-sectional study at twelve months. We chose this approach to reflect similar analyses in the literature.

CONCLUSION

This observational, cross-sectional study showed that there was a lower odds of switching HAART at one year between African-American race compared with Caucasian race. There was no significant difference between Hispanic and Caucasian race. Other race/ethnicity had significant effect on switching HAART regimen at 12 months; however, this group only represented a small proportion of the study cohort. Associations previously demonstrated in the literature may be due to socioeconomic or other confounders which are minimized in this cohort [32]. This study reinforces that clinical factors should be noted by providers when prescribing HAART, including low CD4 count, high HIV viral load, and depression, as these were associated with switching the initial regimen; closer monitoring and management of initial HAART may be warranted in these higher risk patients with HIV infection.

DISCLAIMER

The views expressed are those of the author(s) and do not reflect the official policy or position of the US Army Medical Department, Department of the Army, Department of Defense or the U.S. Government. The investigators have adhered to the policies for protection of human subjects as prescribed in 45CFR46.

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

This study was approved by the ID-IRB at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences.

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

No animals were used in this research. All research procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the committee responsible for human experimentation (institutional and national), and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008 (http://www.wma.net/en/20activities/10ethics/10helsinki/).

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Grace Macalino, PhD and Mr. William Bradley from IDCRP for their contributions. Support for this work (IDCRP-000-03) was provided by the Infectious Disease Clinical Research Program (IDCRP), a Department of Defense (DoD) program executed through the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences. This project has been funded in whole, or in part, with federal funds from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health (NIH), under Inter-Agency Agreement Y1-AI-5072.

Members of the Infectious Disease Clinical Research Program HIV Working Group include the following:

Madigan Army Medical Center, Tacoma, WA: S. Chambers; COL (Ret) M. Fairchok; LTC A. Kunz; C. Schofield

National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Bethesda, MD: J. Powers; COL (Ret) E. Tramont

Naval Medical Center, Portsmouth, VA: S. Banks; CDR K. Kronmann; T. Lalani; R. Tant

Naval Medical Center, San Diego, CA: CAPT M. Bavaro; R. Deiss; A. Diem; N. Kirkland; CDR R. Maves

San Antonio Military Medical Center, San Antonio, TX: S. Merritt; T. O'Bryan; LtCol J. Okulicz; C. Rhodes; J. Wessely

Tripler Army Medical Center, Honolulu, HI: E. Dunn; COL T. Ferguson; LTC J. Hawley-Molloy

Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, MD: B. Agan; X. Chu; T. Fuller; M. Glancey; G. Macalino; O. Mesner; COL S. Miller; E. Parmelee; X. Wang; S. Won

Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, Silver Spring, MD: N. Johnson; S. Peel

Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda, MD: MAJ J. Blaylock; H. Burris; C. Decker; A. Ganesan; LTC R. Ressner; D. Wallace; CDR T. Whitman