All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

A Review of Non-Communicable Diseases (NCDs) Prescribed Medications Instructions to Promote Medication Adherence: A Document Analysis Study

Abstract

Background:

Health literacy is referred to as the individual’s ability to comprehend and follow medication instructions. The aim of the study was to investigate the prescribed medications instructions for user friendliness to enhance health literacy and promote medication adherence in patients with Non-Communicable Diseases (NCDs).

Methods:

A qualitative, descriptive design using checklist rubric was used to conduct the document analysis study. A convenient sampling was used to select 15 Non-Communicable Diseases’ drugs for review from 02 February to 30 April 2018 in Limpopo province, South Africa. Tesch’s eight steps for data analysis was used.

Results:

Fifteen drug leaflets, scripts and packages revealed that there were poor explanation of the frequency of taking the medications and poor information related to the prescribed medication instructions. The findings are however, limited to the study setting and could not be generalised.

Conclusion:

There is a need for further explanation of the medication instructions which includes the frequency of taking medications to be reflected so that patients may consume them at the exact time indicated. The use of symbols on the medication packages should be reviewed. This will assist in reducing mortalities and NCDs complications.

1. INTRODUCTION

Health literacy regarding prescribed medication instructions is important for individuals with Non-Communicable Diseases for proper control and management of these diseases. In this study, Health literacy is referred to as the individual’s ability to comprehend and follow medication instructions. There have been many studies conducted on the prevalence and contributing factors to the Non-Communicable Diseases [1-4]. The studies indicate that there is high prevalence, high risk of determinants and poor management of these diseases [1-4]. However, based on those studies, little is known regarding how patients with the Non-Communicable Diseases interpret prescribed medication instructions.

A study conducted by Koster, Blom, Winters, Hulten and Bouvy [5] indicated that misinterpretation of medication instructions due to health literacy is common in patients with Non-Communicable Diseases causing medication ineffectiveness. This is irrespective of them taking their medications on daily basis as instructed at their health facilities. Research has shown that medication non-adherence and treatment ineffectiveness may be negatively influenced by the inability to comprehend medication instructions; the problem is not with the individuals using the medications alone but also with the medication manufacturers, hence clearer instructions are a necessity to improve adherence to medications instructions [5].

Davis, Federman, Bass III, Jackson, Middlebrooks, et al. [6] indicate that although inadequate health literacy may hinder patients’ understanding of medication instructions, the instructions also may not be written in the most clear and specific way; hence they recommended that more specific wording should be used on prescription medication instructions to enhance patient’s comprehension.

Since poor health literacy related to medication instructions comprehension could lead to poor patient’s health outcomes, increased hospital admissions and readmissions, and consequently increased health cost, it is thus crucial to treat the matter as of urgency. Improving medication instructions give assurance to improve adherence and better clinical outcome. Zullig, Gellad, Moaddeb, Crowley, Shrank, et al. [7] have avowed that there are many health service interventions such as pharmacy driven interventions and educational interventions, which have been put in place to improve medication adherence. So far according to their study Zullig et al. [7] have found that these interventions are less effective due to poor implementation.

The study therefore, sought to investigate the prescribed medications instructions for user friendliness to enhance health literacy and promote medication adherence in patients with Non-Communicable Diseases. The study also is looking forward to identifying the gaps in the medication instructions which could lead to patients misinterpreting them.

2. METHODOLOGY

2.1. Research Design

A qualitative, explorative and descriptive research design was used to explore and describe the information contained in prescribed medication packages, doctor’s prescription, and medication leaflets of NCDs.

2.2. Study Setting

The study was conducted in four clinics (Dikgale clinic, Seobi-Dikgale clinic, Sebayeng clinic and Makotopong clinic) situated at Ga-Dikgale village of the Capricorn District in Limpopo Province, South Africa. Dikgale is an established Health and Demographic Surveillance System (HDSS) which is run by the University of Limpopo with a high prevalence of NCDs, hence it was chosen as a study site.

2.3. Population and Sampling Strategy

Fifteen (15) Non-Communicable Diseases drugs were conveniently sampled from the Twenty two which were available during the time of study. The study included leaflets, medication packages and doctor’s prescriptions for: 02 diabetic drugs, 03 psychiatric drugs, 02 Asthmatic drugs, and 08 anti-hypertensive drugs. These drugs were the only ones available during data collection.

2.4. Data Collection Procedures

Medicine instruction documents i.e., drug leaflets, medication packages and doctor’s prescriptions were reviewed using checklist rubric from 02 February 2018 to 30 April 2018. Any point of interest was jotted down. Data was collected until saturation was reached at drug fifteen.

2.5. Data Analysis

The study adopted Tesch’s eight steps of qualitative data analysis as outlined in Creswell [8]. This includes data preparation, coding, categorising and developing themes and subthemes. The field notes were also analysed to supplement data collected.

2.6. Measures to Ensure Trustworthiness

Trustworthiness was ensured by applying the criteria of Credibility, Dependability, Confirmability and Transferability as outlined by [9].

2.7. Ethical Clearance

Ethical clearance was obtained from the University of Limpopo’s Turfloop Research Ethics Committee (TREC) (TREC/373/2017/PG). Permission to conduct the study was obtained from the Department of Health Limpopo Province (approval number: LP_2017 11 016) and the Nursing managers of Dikgale village clinics.

3. RESULTS

The study results are presented below as reflected on the doctor’s prescriptions, medication leaflets and medication packages. Table 1 below shows the sample description.

| Disease | Number of drugs reviewed |

|---|---|

| Diabetes | 02 |

| Asthma | 02 |

| Psychiatric disorders | 03 |

| Cardiovascular | 08 |

| TOTAL | 15 |

A total number of fifteen (15) NCDs medications instructions were reviewed. This included the drugs leaflets, scripts and packages. During data analysis, two themes and four sub-themes emerged as shown in Table 2 below.

| Themes | Sub-themes |

|---|---|

| 1. Poor explanation of the frequency of taking the medications | 1.1 Lack of time specification for taking medication 1.2 Lack of time interval on the manner to be used when taking medications |

| 2. Poor information on instructions | 2.1 Insufficient explanation of medications instructions 2.2 An observation of usage of unclear symbols used on medication packages |

3.1. Poor Explanation of the Frequency of Taking the Medications

An observation made during critiquing of the doctor’s prescriptions, medication leaflets and medication packages is that medication instructions do not have the exact times for consuming the medications. Two sub-themes emerged from this theme:

3.1.1. Lack of Time Specification for Taking Medication

The reviewed medication’s instructions indicated that there is no exact time specification for taking the medication. e.g., “10 mg daily as a single dose in the evening”. Another one was written, “One tablet twice a day”. This can result in patients taking medication at different times as long as the medication was taken for the prescribed frequency or not at scheduled times consistently. However, the results indicated that all doctor’s prescriptions, medication leaflets and medication packages were clear on how many times the medications should be taken. i.e., “One tablet twice daily”.

3.1.2. Lack of Time Interval on the Manner to be Used When Taking Medications

Of all the medication instructions reviewed, only on medication instruction indicated the time interval for taking the medication. e.g., …preferably at the same time every day”. The other instructions indicated how many times the medications should be taken. i.e., “One tablet daily”.

3.2. Poor Information on Instructions

The study revealed that there is inadequate information on the medication instructions for patients to follow easily and properly. Two sub-themes emerged from this theme namely:

3.2.1. Insufficient Explanation of Medications Instructions

The results revealed deficiency in medication instructions explanation. All the reviewed medication instructions still need further explanation on how the medications should be taken. e.g., “One three times a day” and “One on alternative days”. For someone who is not health literate the said statements might be confusing. These statements need further explanation to give a clearer picture of the meaning of these instructions. The patients can take the medication at any time of the day as long as it was taken three times.

3.2.2. An Observation of Usage of Unclear Symbols Used on Medication Packages

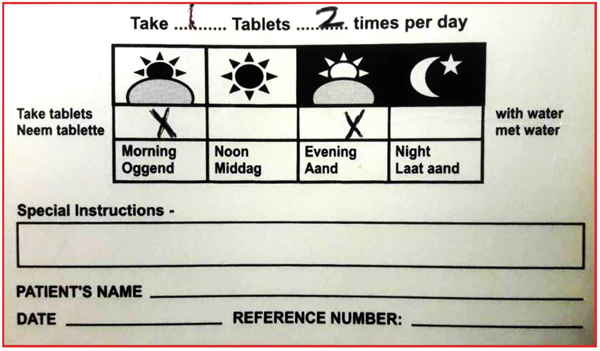

The symbols that are used on the medication packages do not give a clear depiction of how the medication should be taken. e.g., (Fig. 1) above summarises this sub-theme. The picture indicates that the medication should be taken when the sun rises in the morning and when it sets in the evening. This could result in inconsistencies in taking the medication as the sun do not rise and sets at the same time in all seasons and locations.

4. DISCUSSION

This study sought to investigate the prescribed medications instructions to enhance health literacy and promote medication adherence in patients with Non-Communicable Diseases (NCDs). The overall finding of the study revealed that there is poor medication instructions that create confusion about the doctor’s prescription, medication leaflets and medication packages. The study came up with four findings which are elaborated upon in the following sections.

Firstly, the study revealed that the medication instructions are unclear regarding time interval and the exact time for taking medication on the doctor’s prescriptions, medication leaflets and medication packaging, nonetheless there was only one medication that showed time interval for taking that medication. Safeer and Keenan [10] support the findings because they indicated that patients with poor health literacy are incapable of following medications prescription; e.g., “Take 1 tablet X times a day” where X represents a number, the patient might take the medication at incongruous times or intervals, or in the wrong quantities, consequently patients are more likely to understand medication prescription directions and follow them correctly when they are written in this manner; ‘Take 1 tablet every X hours”. If the medication instructions are to be written in a manner that indicates the exact times that the medication is to be taken, the patients are likely to comply. e.g., “Take one tablet at 06h00, 12h00, 14h00, 18h00 or 22h00”. Similar suggestion has been made by Berisa and Dedefo [11] recommending that medications instructions should incorporate the times at which the medications are to be consumed in order to promote adherence. The unfreezing stage of the change theory indicates that there should be a realisation that change is compulsory and preparation to let go of the present comfort zone [12]. The health professional dispensing medication should realise that change is necessary and be willing to further expand the medication instructions given to patients.

Secondly, the study found that the medication instructions could confuse patients because of poor wording, e.g., “10 mg daily as a single dose in the evening”. Another one is written as “3g daily”. The other instructions it reads thus “100 mg daily as a single dose or in divided doses”. These types of instructions still need further explanation as patient might not know what make up 10 mg and what a single dose mean. Hence, there is a need for further explanation on the medication instructions. Shirindi, Makhubele and Fraeyman [13] assert that inadequate health literacy can result in difficulty in following instructions from a doctor e.g., “One tablet BD”, and taking prescribed medication properly, nonetheless, Connelly [12] indicates that during the transition period, support is vital especially in the form of training, coaching, and expecting mistakes as part of the process and further affirms that this stage is yet hardest as the health professionals may be hesitant or fearful for the change. Therefore, the Department of Health could also combat medication non-adherence related to medication instructions misinterpretation through providing education to the health professionals on how they should explain the medication instructions to the patients.

Thirdly, as the results shows that the instructions on the medication leaflets, medication packaging and doctors’ prescriptions are not clear on how to consume the medications. Making the Limpopo Department of Health aware of the consequences of poor medication instructions on patients’ health could promote eagerness to learn what the instructions exactly mean at patient level; consequently, be influenced to approve the idea of motivating for improvement of the medication instructions. This is supported by the unfreezing stage of the change theory which urges that individuals involved need to feel that change is necessary, then change will become urgent and that will motivate the individuals to make the change [12].

Some of the medication packages had symbols which could further confuse the patients on how to take the medication. These symbols show the sunrise, midday full sun, sunset and evening with a moon and stars. The symbols do not say anything about the time and patient may interpret them differently. e.g., summer sunrise differs in time with winter sunrise and in locations. At times it might be cloudy, and the patient might fail to know what time it is. Additionally, the evening might mean 19h00 for one patient while for the other might mean 21h00 etc. This necessitate review of the medication packages as supported by Wolf [14] insisting that “To prevent medication errors; current medication labelling problems which lead to medication errors need to be reviewed and the patient-directed information need to be improved. The freezing stage of the change theory indicates the need for establishing stability after making a change, and individuals in this stage should accept the change and change is regarded as a norm. However, Lewin call this stage based on the argument that there is no time to confine to comfortable routines even after making change has taken place, due to the great flexibility demanded by chaotic processes of the days we live in [12]. Therefore, reviewing of the medication instructions comprehension by patients should always take place; this necessitates continuous research by health departments and health professionals.

5. LIMITATIONS

The study was conducted in four clinics in one village at Capricorn district of Limpopo, South Africa. Only 15 drugs were reviewed due to availability. The findings of the study could therefore not be generalized in other settings.

6. IMPLICATIONS OF THE FINDINGS

These findings confirm that medication instructions need to be reviewed and improved, and that the medication instructions need to be elaborated further and better. Patel, Khan, Ali, Kazmi and Riaz, et al. [15] aver that deficiency in knowledge regarding prescribed medication and medication labels among NCDs patients is a crucial concern.

6.1. Issuing Officers

Health professionals issuing medications need to state the exact times that the patients should take their medications. This can be reflected on the doctor’s prescription and the medication packages.

6.2. Limpopo Department of Health

The Limpopo department of health must request their medication supplying companies to review the medication packages and the symbols should include the exact time which go along with the symbol; e.g., sunrise = 06h00, full sun = 12h00 or14h00, sunset = 18h00, moon = 22h00 or 00h00.

CONCLUSION

The study indicated that information on prescribed medication instructions is unclear and can be confusing to patients. There is a need for further explanation of the medication instructions which includes exact times for medication consumption and the use of symbols on the medication packages need to be reviewed. The recommendations to improve the correct way of taking medications will assist in reducing mortalities and frequent hospitalisation of patients with non-communicable diseases due to complications.

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

Ethical clearance was obtained from the University of Limpopo’s Turfloop Research Ethics Committee (TREC) (TREC/373/2017/PG). Permission to conduct the study was given by the Department of Health Limpopo Province (approval number: LP_2017 11 016), Department of Health Capricorn District and the Nursing manager of the concerned clinics.

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

No animals/humans were used in the studies that is basis of this research.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by the Flemish Interuniversity Council (VLIR UOS Limpopo project), Grant Number: ZIUS2018AP021.