All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Predictors of Poor Self-rated Health in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: Insights from a Cross-sectional Survey

Abstract

Background:

The association between Self-Rated Health (SRH) and poor health outcomes is well established. Economically and socially marginalized individuals have been shown to be more likely to have poor SRH. There are few representative studies that assess the factors that influence SRH amongst individuals in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. This study assessed factors associated with poor self-rated health amongst individuals from KwaZulu-Natal using data from the 2012 South African national household survey.

Methods:

The 2012 South African population-based nationally representative household survey employed a multi-stage stratified cluster randomised crossectional design. Multivariate backward stepwise logistic regression models were used to determine whether SRH is significantly influenced by socio-demographic and health-related factors.

Results:

Out of a total of 5192 participants living in KZN, 18.1% reported having fair/poor SRH. In the multivariate logistic regression model the increased likelihood of reporting fair/poor was significantly associated with being older, HIV positive, being an excessive drinker, and not having medical aid. The decreased likelihood of reporting fair/poor was associated with being educated, not having a chronic condition, being physically active, being employed, and not accessing care regularly.

Conclusion:

This study has shown that marginalized individuals are more likely to have poorer SRH. Greater efforts need to be made to ensure that these individuals are brought into the fold through education, job opportunities, health insurance, social support services for poor living conditions, and poor well-being including services for substance abusers.

1. INTRODUCTION

Self-rated Health (SRH) is an assessment that has been extensively used in epidemiological, social science, and medical research as a proxy gauge of a population’s overall health status [1-3]. Its efficient assessment and its power predicting future morbidity are some of the main reasons for its widespread use. SRH is usually assessed through a single 3 to 5 point scale question asking participants to rate their health from excellent to poor. This simple assessment means that SRH questions can be embedded in larger surveys as measures of health and well-being [4-8].

Poor SRH is linked to waning health and mortality [9-11]. It is therefore theorised that poorer SRH can predict a wide range of adverse health outcomes [9, 11]. In addition, the association between social inequalities and SRH has been established [12-14]. Marginalized individuals in society often report having poorer health [13, 14]. The disparities in health are determined by the circumstances in which individuals are born, live, and work. These circumstances are often determined by factors such as socioeconomic status [13, 14], education [15, 16], employment [7], lifestyle [16, 17], and health status [18].

In South Africa and more specifically in KwaZulu-Natal (KZN), many of the studies that have looked at SRH and its associated factors have looked at specific populations [19]. In addition, there is a scarcity of representative provincial regional data dealing with SRH in South Africa. A study that has had a representative sample of South Africans has shown the importance of contextual factors in influencing SRH [3]. The current study seeks to add to this literature by assessing the contextual factors that predict poor SRH in a representative sample of individuals living in KZN.

2. METHODS

2.1. Data

The data that were used in this analysis were from a nationally representative household survey conducted in 2012. A multi-stage stratified cluster randomised cross-sectional design was employed [20]. A total of 15 Visiting Points (VPs) or households were randomly chosen from 1,000 Enumeration Areas (EAs) which were randomly selected from 86 000 EAs based on the 2001 census EAs. The sampling of EAs was stratified by province and locality type (urban formal, urban informal, rural formal - including commercial farms and rural informal localities).

All individuals living in the selected households were eligible to take part in the survey. Comprehensive and age-appropriate questionnaires were given to participants to solicit sociodemographic and health-related information. This current analysis focused on data collected in KZN from individuals aged 15 years and older who answered questions regarding perceptions about their health.

2.2. Ethical Consideration

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee of the Human Sciences Research Council, South Africa (REC: 5/17/11/10) as well as the Associate Director of Science of the National Center for HIV and AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD and TB Prevention at the USA’s Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in Atlanta, USA. Written informed consent was obtained from all those individuals who agreed to participate.

2.3. Measures

The dependent variable of interest was SRH. This variable was derived from a question that asked participants to rate their health as either excellent, good, fair, or poor. This was recoded into two levels, which were good (excellent/good) SRH (0) and fair/poor (fair/poor) SRH (1), making it a binary outcome.

The independent variables of interest in this study included sociodemographic and health- related variables. The sociodemographic variables of interest were age (15 to 24 years, 25 to 49 years, 50+ years), race (Black African/Other- White, Coloured, and Indians/Asians), sex (male/female) marital status (not married/married), educational level (no education/primary, secondary, tertiary), employment status (not employed /employed), asset-based socioeconomic status score (a composite measure based on availability essential services and ownership of a range of household assets [21] and locality type (urban formal, urban informal, rural informal rural formal).

Health-related variables included, whether individuals had medical aid (yes/no), last healthcare attendance (within the past six months/more than six months but not more than a year ago/more than one year ago/never), hospitalization within the past year (yes/no), physical activity (not active/moderate activity/vigorous activity), alcohol use risk score (non-excessive/excessive) based on a questionnaire for Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT) scale [22], presence of a chronic condition (yes/no), and HIV status (positive/negative).

2.4. Statistical Analysis

In order to describe the association between sociodemographic as well as health-related factors and SRH, frequency distributions and percentages were employed. The Chi-square test was used to test for differences between categorical variables. An adjusted multivariate binomial logistic regression model using backward stepwise selection method set at 0.1 was fitted to determine the sociodemographic and health-related factors that predict poor SRH. Adjusted Odds Ratios (AOR) derived from the coefficient -logit- with 95% Confidence Intervals (CI) was used as a measure of the effect of each variable on SRH. All statistical analyses were significant at a p-value ≤0.05. STATA Statistical Software Release 12.0 was used to conduct the analysis of the data (Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas, USA).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 shows the descriptive attributes of the study sample. A higher proportion of the study sample was aged 25 to 49 years old, were black African female, not married, had a secondary education, of a low SES, unemployed, from rural informal settlements, did not have medical aid, had accessed healthcare within the past six months, had not been hospitalized in the past year, not physically active, non-drinkers/non-excessive drinkers, did not have a chronic condition, and were HIV negative.

Out of a sample of 6192 participants living in KZN, 18.1 % reported having fair/poor SRH. Table 2 shows the sociodemographic characteristics associated with SRH. It shows that reported fair/poor SRH was significantly associated with age, sex, marital status, education, SES, and employment status.

Table 3 shows the health-related factors associated with SRH. It shows that reported fair/poor SRH was also significantly associated with whether or not individuals had medical aid, when they had last visited a healthcare facility, whether or not individuals had been hospitalized, whether or not individuals were physically active, whether or not individual had a chronic condition, alcohol use, and HIV status.

3.2. Multivariate Model

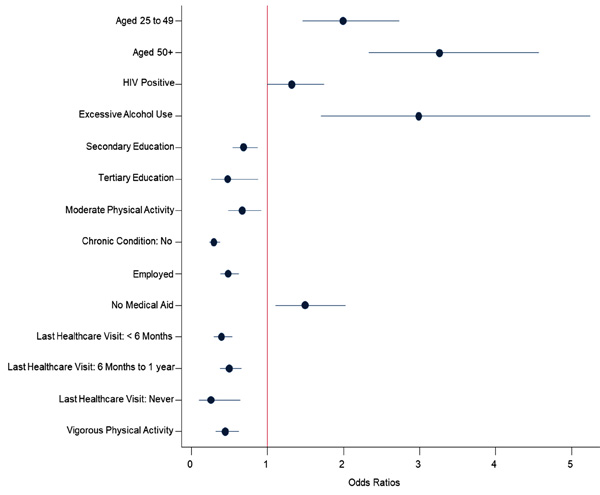

Those aged 25 to 49 [aOR = 2 (1.5-2.7), p < 0.001] and 50 years and older [aOR = 3.3 (2.3-4.6), p < 0.001] were more likely to report fair/poor SRH than those aged 15 to 24. Those who were HIV positive were more likely to have fair/poor SRH compared to those who were HIV negative [aOR = 1.3 (1-1.7), [p = 0.047]. Those who were excessive alcohol drinkers were more likely to have fair/poor SRH compared to those who did not drink excessively or abstained from alcohol [aOR = 2.9 (1.7-5.2), p < 0.001]. Those who completed secondary [aOR = 0.7 (0.5-0.9), p = 0.002] and tertiary education [aOR = 0.5 (0.3-0.9), p = 0.017] were less likely to have fair/poor SRH compared to those who had completed no education/primary education (Fig. 1).

Those who engaged in moderate [aOR = 0.7 (0.5-0.9), p = 0.013] and intense physical activity [aOR = 0.4 (0.3-0.6), p < 0.001] were less likely to have fair/poor SRH compared to those who were not physically active. Those who did not have a chronic condition were less likely to have fair/poor SRH compared to those who had a chronic condition [aOR = 0.3 (0.2-0.4), p < 0.001]. Those who were employed were less likely to have fair/poor SRH compared to those who were unemployed [aOR = 0.5 (0.4-0.6), p < 0.001]. Those who did not have medical aid were more likely to have fair/poor SRH compared to those who had medical aid [aOR = 2.1 (1.1-2), p = 0.009]. Those who last accessed healthcare 6 to 12 months prior [aOR = 0.4 (0.3-0.5), p < 0.001]; more than a year prior [aOR = 0.5 (0.4-0.7), p < 0.001]; or have never accessed healthcare [aOR = 0.3 (0.1-0.6), p = 0.004] were less likely to have fair/poor SRH compared to those who accessed care within the previous 6 months (Fig. 1).

| – | n | % | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Years) | |||

| 15 to 24 | 1706 | 31.9 | 30.1-33.6 |

| 25 to 49 | 2671 | 48.5 | 46.2-50.8 |

| 50+ | 1883 | 19.7 | 17.9-21.6 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 2612 | 45.6 | 43.2-48.1 |

| Female | 3649 | 54.4 | 51.9-56.8 |

| Race Group | |||

| Black African | 3231 | 88.5 | 84.3-91.8 |

| Other Race Groups | 3026 | 11.5 | 8.2-15.7 |

| Marital Status | |||

| Not Married | 3992 | 79.3 | 76.7-81.6 |

| Married | 2183 | 20.7 | 18.4-23.3 |

| Education Level | |||

| No education/Primary | 1011 | 21.8 | 19-25 |

| Secondary | 4110 | 71.8 | 69.1-74.4 |

| Tertiary | 413 | 6.3 | 4.7-8.5 |

| Asset-based SES | |||

| Low | 2318 | 64.2 | 55.5-72.1 |

| Middle | 1615 | 23.2 | 16.7-31.3 |

| High | 2258 | 12.6 | 9.3-16.9 |

| Employment Status | |||

| Employed | 2200 | 31.8 | 28.4-35.4 |

| Unemployed | 3659 | 68.2 | 64.6-71.6 |

| Locality type | |||

| Urban formal | 3773 | 31.2 | 21.2-43.2 |

| Urban informal | 533 | 9.4 | 5-16.9 |

| Rural informal | 1437 | 54.9 | 42.6-66.7 |

| Rural formal | 518 | 4.5 | 2.1-9.5 |

| Medical Aid | |||

| Yes | 1305 | 12.5 | 9.7-15.9 |

| No | 4858 | 87.5 | 84.1-90.3 |

| Last Healthcare Attendance | |||

| Within the past six months | 3219 | 45.5 | 42.7-48.4 |

| More than six months but not more than a year ago |

1253 | 21.1 | 18.6-24 |

| More than one year ago | 1474 | 28.1 | 25.1-31.4 |

| Never | 232 | 5.2 | 3.9-6.9 |

| Hospitalization | |||

| Yes | 396 | 5.1 | 4.1-6.5 |

| No | 5783 | 94.9 | 93.5-95.9 |

| Physical Activity | |||

| Not Active | 4046 | 68.5 | 65.5-71.3 |

| Moderate Activity | 849 | 7.5 | 6-9.5 |

| Vigorous Activity | 1291 | 24 | 21.3-26.9 |

| Alcohol Use | |||

| Non-drinkers/ Non-excessive drinkers |

5565 | 97.1 | 96-97.8 |

| Excessive drinkers | 131 | 2.9 | 2.2-4 |

| Chronic Condition | |||

| Yes | 1362 | 19.1 | 16.4-22 |

| No | 4816 | 80.9 | 78-83.6 |

| HIV Status | |||

| Negative | 4292 | 75.1 | 72.5-77.6 |

| Positive | 736 | 24.9 | 22.4-27.5 |

| – | n | Fair/Poor | – | – |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| – | – | % | 95% CI | p-value |

| Total | 6 192 | 18.1 | 15.3-20.8 | – |

| Age (Years) | ||||

| 15 to 24* | 1 688 | 7.2 | 5.1-10.1 | < 0.001 |

| 25 to 49 | 2 636 | 16.6 | 13.4-20.3 | |

| 50+ | 1 868 | 39.1 | 33.9-44.5 | – |

| Sex | ||||

| Male* | 2 582 | 15 | 11.7-19 | 0.003 |

| Females | 3 610 | 20.6 | 17.9-23.7 | – |

| Race Group | ||||

| Black African* | 3 189 | 18.2 | 15.3-21.6 | 0.575 |

| Other Race Group | 3 000 | 16.9 | 13.7-20.6 | – |

| Marital Status | ||||

| Not Married* | 3 965 | 17 | 14-20.3 | 0.009 |

| Married | 2 173 | 22.4 | 18.9-26.4 | – |

| Education Level | ||||

| No education/Primary* | 1 000 | 28.7 | 23-35.2 | < 0.001 |

| Secondary | 4 069 | 12.5 | 10.3-15.1 | – |

| Tertiary | 410 | 9.9 | 6.6-14.5 | – |

| Asset-based SES | ||||

| Low* | 2 288 | 19.9 | 16.3-24 | 0.046 |

| Middle | 1 593 | 14.5 | 11.1-18.8 | – |

| High | 2 246 | 15.3 | 12.4-18.8 | – |

| Employment Status | ||||

| Employed* | 3 633 | 9.9 | 7.3-13.4 | < 0.001 |

| Unemployed | 2 190 | 21 | 17.8-24.6 | – |

| Locality type | ||||

| Urban formal* | 3 737 | 16 | 12.9-19.8 | 0.155 |

| urban informal | 526 | 20.4 | 15.5-26.3 | – |

| rural informal | 1 423 | 19.4 | 15.3-24.3 | – |

| rural formal | 506 | 10.7 | 6.9-16 | – |

| n | Fair/Poor | – | – | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | 95% CI | p-value | ||

| Total | 6 192 | 18.1 | 15.3-20.8 | |

| Medical Aid | ||||

| Yes* | 1 305 | 13.8 | 10.3-18.2 | 0.052 |

| No | 4 851 | 18.5 | 15.7-21.8 | – |

| Last Healthcare Attendance | ||||

| Within the past six months* | 3 217 | 27.7 | 23.3-32.7 | < 0.001 |

| More than six months but not more than a year ago | 1 254 | 10 | 7.2-13.7 | – |

| More than one year ago | 1 472 | 10.8 | 8.1-14.2 | – |

| Never | 232 | 4.2 | 1.7-10.1 | – |

| Hospitalization | ||||

| Yes* | 395 | 31.1 | 20.9-43.4 | 0.008 |

| No | 5 778 | 17.3 | 14.7-20.4 | – |

| Physical Activity | ||||

| Not Active* | 4 042 | 22.7 | 19.3-26.5 | < 0.001 |

| Moderate Activity | 847 | 13.7 | 9.7-18.9 | – |

| Vigorous Activity | 1 290 | 6.2 | 4-9.4 | – |

| Alcohol Use | ||||

| Non-excessive drinkers* | 5 557 | 17.2 | 14.8-20 | 0.004 |

| Excessive drinkers | 131 | 29.9 | 19.5-42.9 | – |

| Chronic Condition | ||||

| Yes* | 1 360 | 47.3 | 41-53.8 | < 0.001 |

| No | 4 811 | 11.1 | 9.1-13.5 | – |

| HIV Status | ||||

| Negative* | 4 256 | 16.6 | 14-19.6 | 0.001 |

| Positive | 723 | 22.6 | 17.9-28.1 | – |

4. DISCUSSION

Although the current study focuses on the province of KwaZulu-Natal, the findings revealed that the proportion of individuals who reported fair/poor health is similar to previous findings from other South African studies, which were both provincially and nationally representative [3, 19]. Selected sociodemographic and health-related factors; such as age, HIV status, alcohol use, education, physical activity, whether or not individuals had a chronic condition, employment status, whether or not individuals had medical aid, and how recently they had last seen a healthcare practitioner were seen to predict poor SRH.

The finding that unemployment and lower education negatively affects SRH is similar to previous findings from a study conducted in South Africa [19]. Therefore, these findings suggest that interventions that decrease inequalities in employment and education would result in improved SRH and health in general.

This study also found that individuals who were less physically active and those who were excessive alcohol drinkers were more likely to report poor SRH is not surprising. Lifestyles have also been shown to influence SRH and health in general [16, 23]. Poor lifestyle choices are often related to the onset of disease, particularly cancers, diabetes, stroke, respiratory and digestive diseases [23].

The link between physical activity and SRH has been made previously while studies assessing the link between SRH and alcohol abuse have been more sparse, even though the link between objective measures of health and alcohol abuse is well established with poorer health related to alcohol abuse [16, 24-26]. The current findings reiterate the negative health consequences of physical inactivity and alcohol abuse [27, 28].

The link between SRH and more objective measures of health is well established [1]. It was therefore not surprising to find that those individuals afflicted with HIV and other chronic conditions reported poorer health. Even in the context widespread antiretroviral treatment use, those who are HIV positive are still more likely to view themselves as having poorer health [29]. The finding that individuals who are HIV positive are more likely to view themselves as having poorer health, even in the context of widespread antiretroviral treatment use, may also suggest that there is a mental component of SRH as those living with HIV have been shown to be more likely to experience depressive symptoms as a result of the stigma and anxiety that results from being HIV positive [30].

5. LIMITATIONS

The current study is based on data from a cross-sectional survey. This study can therefore not establish true cause and effect between the sociodemographic as well as health-related factors and SRH. Furthermore, the study relies on data that are self-reported and is therefore, limited by the recall and social desirability bias. Nevertheless, probability sampling ensures that the current findings can be generalized for those 15 years and older in the province of KwaZulu-Natal.

CONCLUSION

This study has shown that marginalized individuals are more likely to have poorer SRH. Greater efforts need to be made to ensure that these individuals are brought into the fold through education and job opportunities. Including social services for poor living conditions and poor well-being, provision of health insurance, incorporating health promotion initiatives as part of social support and public services for substance abusers.

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee of the Human Sciences Research Council, South Africa (REC: 5/17/11/10) as well as the Associate Director of Science of the National Center for HIV and AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD and TB Prevention at the USA’s Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in Atlanta, USA.

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

No animals/ humans were used for the studies that are the basis of this research.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to data collection.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

The dataset(s) could be available through the Human Sciences Research Council data research repository via access dataset http://www.hsrc.ac.za/en/research-data/ upon request.

FUNDING

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest. This study has been supported by the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) under the terms of 5U2GGH000570. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the CDC.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the fieldworkers and other Human Sciences Research Council staff who assisted in the collection of the data. LM analysed the data. LM, LM, MM, and KZ wrote the manuscript.