All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Early Newborn Bath and Associated Factors among Parturient Women Who Gave Birth in the Last Month in Harar Region, Eastern Ethiopia, 2017.

Abstract

Background:

Neonatal thermal care is a vital intervention as newborns are susceptible to hypothermia than adults for certain reasons such as having a large body surface area, thin skin, little insulating fat, and overwhelmed thermoregulation mechanisms. Many newborn complications develop because of hypothermia due to thermal care malpractices. The leading thermal practice by women of developing countries is early bathing which predisposes newborns for life-threatening situations, such as low blood sugar levels, respiratory distress, abnormal clotting, jaundice, pulmonary hemorrhage and increased risk of developing infections. Hence, this research is aimed to provide substantial evidence regarding the women’s practices of newborn bath and the factors that determine early (<24hr) bathing.

Objective:

The study aimed to assess the early newborn bath and its associated factors among parturient women who gave birth in the last month in the Harar region, Eastern Ethiopia, 2017.

Methods:

The study applied an institutional-based cross-sectional study design by recruiting 433 women. The data collectors interviewed study participants face to face at the baby immunization ward from two hospitals and four health centers. The author calculated the sample size using a double population proportion formula. A systematic sampling technique from the women’s medical registration frame was used to select the final study participants. The data collectors gathered the data using a structured questionnaire adapted from different literature, checking its consistency, reliability and validity by a pretest.

Results:

The response rate of this study was 99.8%. The early newborn bathing practice was found in 153 (35.4% with 95% (CI): (30.3%, 40.3%) women. Uneducated (AOR=3.12 95% CI: (2.12-5.3), no knowledge of hypothermia (AOR=4.95 95% CI: (3.10-12.2), being Primi para (AOR=3.5 95% CI: (2.5-5.6) and no utilization of newborn bed net (AOR=6.2 95% CI: (3.3-45) were statistically significant factors determining early newborn bathing practice.

Conclusion:

The study revealed that although the ministry implemented a good deal of awareness promotion activities, women still practice early newborn bathing. Maternal illiteracy, giving birth for the first time, knowledge deficiency related to hypothermia and newborn bed net application were among the factors which demand improvement to solve the problem.

1. INTRODUCTION

Neonatal thermal care is a vital intervention as newborns are susceptible to hypothermia, even in hot climates. For newborns, the warmth needs to be maintained immediately after birth to prevent heat loss. This is because newborns have a large body surface area, thin skin, little insulating fat, and overwhelmed thermoregulation mechanisms compared to adults. Thus, heat loss in newborns is four times more heat per unit body weight than adults [1, 2]. The provision of thermal protection permits the newborn to preserve their body warmth, particularly since the preterm babies are at higher risk of heat loss [3]. Hypothermia because of early bathing, therefore, causes potentially life-threatening situations, such as low blood sugar levels, respiratory distress, abnormal clotting, jaundice, pulmonary hemorrhage and increased risk of developing infections [4]. Hence, delaying bathing up to 24 hours has a significant benefit for the baby and the woman by promoting breastfeeding, facilitating skin to skin contact with the woman, and leaving the vernix intact used to prevent hypothermia. Early newborn bathing makes temperature regulation more difficult. Hence, washing the vernix enables newborns to maintain warmth throughout the first 24 hours of life. Therefore, postponed bathing to 24hr is one mechanism to reduce hypothermia in newborns from 29% to 14% [5, 6]. However, traditional beliefs are yet barriers to the intervention. A qualitative study of thermal care beliefs and practices in three African countries (Ethiopia, Nigeria &Tanzania) revealed that traditional beliefs are still contributing to the practice of early newborn bathing. In the study, the women’s belief that birth fluid causes body odor later in life, the desire to look at their baby clean and presentable to visitors and looking dirty were some reasons found for early bathing [7]. According to the World health organization (WHO) and save the children’s endorsement on newborn care interventions, bathing should be delayed to at least 24 hours after birth unless cultural reasons inhibiting the practice. However, when cultural reasons prohibit the intervention, women must postpone newborn bathing for at least 6 hours to minimize the risk of neonatal hypothermia. In addition, the newborn’s ambient temperature needs preservation using appropriate clothing like a hat [8]. Despite maintaining neonatal warmth being an initial point to reduce neonatal morbidity and mortality, the data shows that the problem is yet understudied so far especially in low resource and low awareness countries like Ethiopia. Hence, this research is aimed to provide substantial evidence regarding the women’s practices of newborn bath and the factors that determine early (<24hr) bathing.

2. METHODS AND MATERIALS

2.1. Study Setting, Period and Design

The study was conducted in the Harar regional state of the Eastern part of Ethiopia from March 1-30/2017. The regional infant (IMR) and neonatal mortality (NMR) rate of the town was 66 and 33 deaths per 1,000 live births, respectively [9]. The study applied an institutional-based cross-sectional study design by recruiting 433 women who presented during baby immunization in different health facilities (two hospitals and four health centers). Besides, the study allowed women from the immediate postnatal period to take part, aiming to minimize the risk of recall bias.

2.2. Sample Size Determination, Data Collection Method, and Tool

We calculated the sample size using double population proportion formula after reviewing some variables from different literature, assuming 80% power, the ratio of exposed to unexposed equivalent to 1. Thus, comparing prior exposure of women to primary education with that of not taking formal education yielded a sample size of 433 participants. The study used a structured questionnaire adapted from different literature and its consistency was checked through a pretest. The data was collected through face to face interview with each woman. The data collectors were ten diploma midwives organized into five groups (to minimize bias and errors during the data collection process). The authors provided training and information to the data collectors regarding the aim of the study, method of data collection, reliability, and validity of the tool.

2.3. Operational Definitions

Early bathing: - The immersion of all or part of the body of a newborn in water or some other liquids for cleansing or refreshment before 24hr after delivery [8]

Late bathing: - Delaying baby's first bath until 24 hours after birth or waiting at least 6 hours if a full day is not possible for cultural reasons [8].

Maternal knowledge: - Women’s capability of recalling 3 or more out of ten WHO recognized newborn danger signs without interviewer’s prompt-measured maternal knowledge about newborn danger signs [10].

Parity is the number of births the women had after fetal viability (>28 weeks) including stillbirth. But, operationally, it is defined as how many live births the women had, as only having live births provides with the opportunity to practice the intervention.

2.4. Data Processing and Analysis

The data were first coded, entered and cleaned using Epi data statistical software version 3.1 and then exported to SPSS statistical software version 20 for analysis. The data clerk ran bivariate analysis in the logistic regression to evaluate the association between each independent variable and the outcome variable by using binary logistic regression. All variables with p-value ≤ 0.25 were computed into the multivariate model to control the confounders. Finally, the adjusted odds ratio along with 95% CI was estimated to identify factors associated with early newborn bathing. The level of statistical significance was declared at p-value < 0.05.

2.5. Ethical Considerations

Before the initiation of the data collection process, an informed, written and signed consent was obtained from each participant requested by the head of the health facilities. The data collectors informed participants about the purpose and benefits of the study. Besides, parental consent was also obtained for participants aged under 16. The confidentiality of the study participants was also ensured.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Women’s Sociodemographic Factors

The response rate of this study was 99.8%. Most of the women 393(91%) were urban residents, 261(60.4%) housewives , 206 (47.7%) Muslim in religion and 199(46.1%) Oromo in ethnicity. The mean age of women was 26.13, with most 381(88.2%) of the women in the age group of 18-31 years. Regarding the women's education status, 314(80.6%) took formal education, out of whom 114(36.3%) had attended primary school, 111(35.4%) secondary school and 89(28.3%) attended college and above. Similarly, 333 (77%) husbands of the mothers under study were educated to different levels; 159(36.8%), 106(24.5%) and 92(21.3%) had primary, secondary education and above college, respectively.

3.2. Timing of a Newborn Bath

Our study revealed that the number of women who bathed their newborns within the first 24 hours was 153 (35.4% with 95% CI: (30.3%, 40.3%). Hence, this is an implication that many women are still practicing against the WHO and save the children's recommendation regarding the timing of newborn bath (Fig. 1).

3.3. Women’s knowledge about Newborn Danger Signs

Regarding the knowledge, 302(69.9%) women knew about the WHO recognized newborn danger signs without prior knowledge from the interviewer, whereas 130(30.1%) women never notified about newborn danger signs. Out of the 302 women, 90 (20.8%), 70(16.2%) and 142(32.9%) mentioned 1, 2 and ≥3 newborn danger signs, respectively. Meanwhile, 246(61.1%) women were aware of newborn danger signs and a few 162(37.5%) women mentioned hyperthermia and hypothermia as newborn danger signs, respectively.

3.4. Women’s health Service Factors

This study showed that most 352(81.5%) of the women gave birth to their last baby in the hospital. The remaining 61(14.1%), 17(3.9%) and 2(0.5%) gave birth in the health center, private hospital, and home, respectively. Besides, health professional assisted deliveries were 415 (96.1%). The remaining women 10(2.3%), 4(0.9%), 3(0.7%) were assisted by Traditional Birth Attendants (TBA), health extension workers (HEW) and family, respectively (Table 1).

| Variables | - | Frequency | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recent Antenatal care (ANC follow up) (N= 432) |

Yes (n=393) | One | 42 | 10.7 |

| Two | 94 | 23.9 | ||

| Three | 96 | 24.4 | ||

| Four and above | 161 | 41 | ||

| No (n=39) | - | 39 | 9 | |

| ANC attendant (n=393) |

Doctors | - | 87 | 22.1 |

| Health officer | - | 21 | 4.9 | |

| Nurse midwife | - | 285 | 72.5 | |

| ANC get counseled (n=393) |

Yes | 354 | 90.1 | |

| No | 39 | 9.9 | ||

| Counseled about baby hygiene (n=354) | Yes | 278 | 78 | |

| No | 76 | 21.5 | ||

| Counseled about baby immunization(n=354) | Yes | 241 | 68.1 | |

| No | 113 | 31.9 | ||

| Recent postnatal care (PNC follow up) (N= 432) |

Yes | 145 | 33.6 | |

| No | 287 | 66.4 | ||

3.5. Obstetric Factors of the Women

The results of the women regarding their previous obstetric history showed that 248 (57.4%) gave birth through spontaneous vaginal delivery (SVD), 148(34.3%), by cesarean section and only a few 36(8.3%) gave birth by instrumental assisted vaginal deliveries. Meanwhile, the total mean (number of live births women had including the latest baby) was 1.94. Hence, almost half of the women were Multi para 232(53.7%), 182(42.1%) Primi para and 18(4.2%) were grand multiparas.

3.6. Newborn Care-related Factors

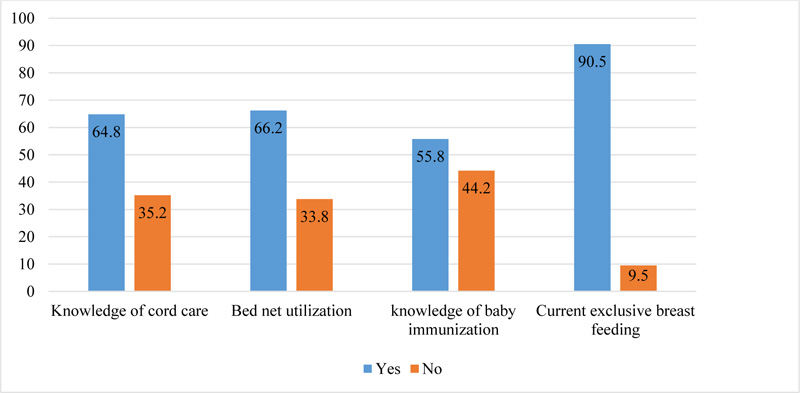

According to the women’s newborn care practice, from 280 women who knew about cord care, 165(58.9%) mentioned sterile cord clamp as a cord tie material whereas, few 13(4.6%) stated unsterile material as a clamp. But the remaining 102 (36.4%) women did not know what to use as cord tie material. Similarly, 219 (78.2%) women stated nothing should put on the cord, 41(14.6%) mothers stated butter is safe and few 20(7.1%) women mentioned antiseptic solutions. Regarding the time of breastfeeding initiation majority, 306(70.8%) women fed their babies within one hour of the delivery (Fig. 2).

3.7. Factors Associated with Timing of a Newborn Bath

3.7.1. Results of Bi-variable and Multivariate Logistic Regression Analysis

The study assumes early bathing (within 24hrs) as a predictive probability in the due process of analysis. Thus, the Bi-variate result showed that women educated at primary level were [(COR= 2, 95% (1.15, 3.7)] times more inclined to bathe their newborn baby <24hr after delivery compared with those educated to college and above. Similarly, women whose husbands had no education [(COR= 1.45, 95% (0.79, 2.6)] were more likely to bathe their newborns within 24hrs than those educated to college and above. The women who did not know about cord care [(COR= 1.5, 95% (1.04, 2.3)] were more likely to practice early bathing. Also, the multivariate analysis revealed that Primi para women, no knowledge about hypothermia, women’s illiteracy, and not using bed net for both the woman and baby were the most statically significant factors that determined early newborn bathing (Table 2).

4. DISCUSSION

Neonatal hypothermia is one of the definite causes of many newborn complications. Thus, the WHO recommended delaying newborn bathing up to 24hrs as an approach to tackle neonatal morbidity and mortality. In our study, the overall early bathing practice by women accounted for 153 (35.4% with 95% CI: (30.3%, 40.3%). This result is consistent with the study conducted in Bahir Dar city, Northwest Ethiopia, which was 36.2% [11], Damot pulasa Woreda, southern Ethiopia 35.7% [12]. This implicates that although the federal minister of Ethiopia (FMOH) is taking measures to reduce the problem through training health care providers, mobilizing campaigns of health education by establishing a special task force called health extension workers, many women are still bathing their babies earlier than 24 hours postpartum. Improved bathing practice computed from the study conducted in Dessie Referral Hospital in Ethiopia and Bangladesh was 24% and 13% respectively compared to our study [13-15]. The discrepancy may emerge due to the following reasons; 1) the first reference study was carried out in the early post-partum period excluding recall bias introduction during data collection. 2) Even though the sociocultural differences might cause newborn care practice differences, Ethiopia is still progressing lately to achieve the standard of basic and essential newborn care practices.

In contrast, studies from Awabel District, Amhara regional state of Ethiopia in [13], Mandura District, Northwest Ethiopia [16] and a study from Malawi [14] showed early bathing practice to be 65%, 62.2%, and 74% respectively, which was higher than the finding of our study. The high rate of malpractice may be due to the fact that all the studies have been conducted in the rural areas where women lack information regarding basic newborn care practice.

| Independent Variables | Frequency (%) | Time of Newborn Bath | COR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| >24hr | <24hr | ||||

| Age of the mother | - | ||||

| <18 | 7(1.6) | 2 | 5 | 3.3 (0.75, 18.8) | - |

| 18-31 | 381(88.2) | 252 | 129 | 0.67(0.36, 1.27) | - |

| >31 | 44 (10.2) | 12 | 38 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Time of breast feeding initiation | - | ||||

| <1 hour | 306 (70.8 | 188 | 118 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| >1 hour | 126 (29.2) | 91 | 35 | 1.63(1.04-2.6) | - |

| Maternal educational status | - | ||||

| Yes | 314 (72.7) | 233 | 81 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| No | 118 (27.3) | 46 | 72 | 4.5(2.87, 4.28) | 3.12(2.12, 5.3)* |

| Parity | - | ||||

| Primi para | 182(42.1) | 70 | 112 | 4.8(1.8, 13.2) | 3.5(2.5, 5.6)* |

| Multi para Grand multi para |

232 (53.7) 18(4.2) |

199 10 |

33 8 |

0.20(0.08, 0.56) 1.00 |

1.00 |

| ANC counseling about baby immunization | - | ||||

| Yes | 241 (68.1) | 145 | 96 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| No | 113 (31.9) | 79 | 34 | 1.5(0.95, 2.5) | - |

| Current PNC visit | - | ||||

| Yes | 145 (33.6) | 86 | 59 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| No | 287 (66.4) | 193 | 94 | 1.4(0.93, 2.1) | - |

| Knowledge of hypothermia | - | - | - | - | - |

| Yes | 162 (53.6) | 126 | 36 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| No | 140(46.4) | 64 | 76 | 4.2(2.5-6.8) | 4.95(3.10, 12.2)* |

| Current exclusive breast feeding | - | ||||

| Yes No |

391 (90.5) 41(9.5) |

249 30 |

142 11 |

1.00 1.6(0.76, 3.2) |

1.00 |

| Bed net utilization | - | ||||

| Yes | 286(66.2) | 211 | 75 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| No | 146(33.8) | 68 | 78 | 3.2(2.1, 4.9) | 6.2(3.3, 45)* |

| Knowledge on WHO recognized newborn danger signs | - | ||||

| One | 90(29.8) | 44 | 46 | 1.4(0.84, 2.4) | - |

| Two | 70(23.2) | 64 | 6 | 0.13(0.052, 0.32) | - |

| Three and above | 142(47) | 82 | 60 | 1.00 | - |

In our study, women who did not take formal education, lacked knowledge about hypothermia, had poor cord care practice and had not attended ANC visits were more likely to bathe their baby < 24 hours compared to their counterparts. This is in line with the study conducted in Awabel District, Amhara regional state of Ethiopia [13], Dessie Referral Hospital in Ethiopia [15] and Mandura District, Northwest of Ethiopia [16]. Hence, all studies revealed that educated women, those who know about thermal care and had ANC follow-ups were more likely to bathe their baby >24 hours. In our study, women who had childhood bed net utilization (66%) were less likely to bathe within 24hrs, which is in accordance with the study conducted in Bo, Sierra Leone which was 53.4% [17]. The study also introduced that Primi para (1 live birth) women were more likely to bathe their newborn baby within 24hrs compared to multiparas (2-4 live birth) and grand multipara (≥5 live births). This is because Primi women lack knowledge of birth experiences related to their newborn care practice.

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

This study presented issues related to the magnitude of early bathing practice and the factors that contribute to the malpractice. Although the Ethiopian minister of health implements awareness promotion activities by providing routine counseling and campaign about newborn care during antepartum and postpartum periods, women still practice early newborn bathing. Maternal illiteracy, giving birth for the first time, knowledge deficiency related to hypothermia and lack of bed net application to their newborns were among the factors that demand improvement to solve the problem. Thus, women need to empower academically; FMOH should introduce routine counseling about the danger of early newborn bathing by integrating the service into ANC and PNC besides providing training to birth attendants.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| WHO | = World Health Organization |

| IMR | = Infant Mortality Rate |

| NMR | = Newborn Mortality Rate |

| TBA | = Traditional Birth Attendant |

| HEW | = Health Extension Worker |

| ANC | = Antenatal Care |

| PNC | = Postnatal Care |

| SVD | = Spontaneous Vaginal Delivery |

| FMoH | = Federal Minister of Health |

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

Ethical clearance was secured by Haramaya University Institutional Health Research Ethics Review Committee, Ethiopia.

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

Not applicable.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

All the participants who participated were informed verbally about the study and those who gave written informed consent were enrolled.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA & MATERIALS

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author [F. T. W.], upon reasonable request.

FUNDING

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank the heads of each public health facility, Harar region health office and data collectors who invested undeserved effort by providing input in developing this research paper.