All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Experiences Leading to the Choice of Termination of Pregnancy Amongst Teenagers at a Regional Hospital in Mpumalanga Province, South Africa

Abstract

Background:

In order to promote women’s rights relating to their sexual and reproductive health, termination of pregnancy in South Africa was introduced. Health professionals are expected to assist women in realizing their wishes if they want to terminate unwanted pregnancies. Unfortunately, women still experience challenges relating to the Termination of Pregnancy, more specifically, pregnant teenagers.

Aim:

The purpose of this study was to describe and explore the occurrences leading to the termination of pregnancy amongst teenagers.

Methods:

The qualitative research method was adopted to determine occurrences related to the Choice of Termination of Pregnancy amongst teenagers in Mpumalanga Province. Data were collected by conducting semi-structured interviews with teenagers to gain insight into the phenomenon studied. Permission to conduct the study at the hospital was obtained from the Department of Health Mpumalanga Province and written informed consent was obtained from participants prior to the sessions. Teenagers between the ages of 13-19 years who opted for, or had already, terminated their pregnancy participated in the study.

Results

The study revealed that the termination of unplanned pregnancy amongst teenagers was influenced by different life experiences. Those experiences are 1) the concern of being rejected by parents and other family members, 2) fear of being ridiculed by peers and the entire community, 3) feelings of embarrassment and shame, and 4) how the teen’s parents are likely to react when they are made aware of the pregnancy.

Conclusions and Recommendations:

The study revealed different circumstances, which contributed to the decision of some pregnant teenagers to opt for the termination of their pregnancy. It is of vital importance that support services be available continuously for the teenagers who opted for termination of pregnancy. More importantly, the supportive environment created by family members and close friends is of the utmost importance, because they are better placed to see the changes or see how the teens are coping pre- and post-abortion. This will enable teenagers to feel that they are not alone and enable them to cope in both pre-and-post phases.

1. INTRODUCTION

Adolescent years are the most important and difficult time of life. During this time different individuals become independent, build new relationships, develop social skills and learn behaviours that might last the rest of their lives. It is the time when adolescents face sexual health issues such as sexually transmitted diseases, teenage pregnancy or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) (World Health Organization [1]. In developing countries, total 21 million girls are aged between 15 and 19 years and 2 million girls become pregnant annually, which exposes them to the risk of sexual and reproductive health problems. Teenagers between the ages of 15 and 19 years give birth every year, while they don’t want to have the children. They have different experiences, which lead them either to keep their babies or opt for Termination of Pregnancy (TOP) [2]. Globally between 2010 and 2014, it has been estimated that 56 million (safe and unsafe) abortions were performed each year [3].

In South Africa (SA), the Termination of Pregnancy (TOP) was legalised in 1996 based on the constitutional charter of Human Rights, which allows everyone freedom of choice, including, the right over procreation. The Termination of Pregnancy Act, no.92 of 1996 states, women can exercise their constitutional rights to reproductive choice and can request and give consent to abortion [4]. Since the passing of the Termination of Pregnancy Act, which legalised voluntary abortion, the ethical question around this issue has been the topic of much public and private debate [5]. Cultural beliefs were some of the reasons nurses chose not to provide these services to teenagers who requested CTOP, but they do refer them to other health care professionals [4, 6]. In the study conducted by Govender, the majority of nurses were not in favour of the legislation and provision of the abortion services to teenagers, yet their profession is built on the principles of care and empathy towards their patients [7]

It is essential to note that the decision to have children is fundamental to women’s physical, psychological and social health and what the person who is pregnant is experiencing [8]. The Democratic Nurses Organisation in South Africa (Denosa) has published a position paper on this issue, in which it affirms that every woman has the right to freedom of choice, appropriate referral systems, respect to the individuals' dignity as well as provision of supportive and neutral counselling before and after the termination of pregnancy [9].

In South Africa, Stampler and Flemmit (2017) reported that though there was a decline of 90% after the legalisation of the Choice of Termination of Pregnancy (CTOP) Act, there was still over 90 000 illegal TOP which were performed in this country by 2017 [10]. Although TOP was legalised in SA, there are still gaps observed for proper implementation of the activities such as lack of registered TOP clinics in certain areas. The stigma still associated with TOP could be the reason behind the high number of illegal termination of pregnancies in SA.

The decision about the termination of a pregnancy is considered to be urgent and might be made without any emotional conflict because once the teenager has become pregnant her unintended pregnancy develops rapidly whilst she has to come to terms with the situation and how to resolve it [11, 12]. Several issues could convince teenage girls and women to instead opt for illegal abortions. An illegal abortion could cause haemorrhaging, toxic shock, sepsis, scarring of the cervix and death. The danger to a woman's health due to an illegal abortion was one of the reasons that prompted a change in South African legislation concerning TOP [13].

Unwanted pregnancy has an impact on a teenager's life, which increases practices such as dumping of foetuses for example. Legislation permits TOP to protect the teenager's mental and physical health [14]. The psychological distress suffered by teenagers caused by social and or economic circumstances related to pregnancy demands might be worsened by keeping an unwanted pregnancy. Therefore, TOP might be an option [15]. The woman’s life may be threatened with serious or permanent injury due to illegal termination of her pregnancy. Socio-economic factors such as economic resources, the teenager’s age and marital status are all contributory factors towards deciding to terminate the pregnancy [16]. Termination of pregnancy in some countries is generally interpreted as being liberal. Numerous countries, including South Africa (SA), explicitly allows TOP on grounds such as rape, incest, and foetal impairment. In SA, the TOP Act No 1 of 1998 stipulates that a pregnant teenager is entitled to termination of pregnancy on request within the first 12 weeks of pregnancy [4].

Additionally, factors that influence TOP decision-making include cultural, psychosocial and economic situations [17]. A pregnant teenager is confronted with countless experiences of unplanned pregnancies from incest or sexual abuse that might influence her decision of either keeping or terminating the pregnancy. Educating the teenager first is an option so that an informed decision could be taken [12]. For many of the adolescents, teenage pregnancy and early childbirth means an end to their education, increased poverty and lack of options (Foundation for Women’s Health, Research, and Development & International Planned Parenthood Federation (IPPF) International Planned Parenthood Federation [18].

The primary researcher discovered that the teenagers seem to be having negative experiences such as stigmatization and name calling (outcast) by parents, peers and community members, this led them to request CTOP in the Mpumalanga hospital. The teenagers indicated during history taking that their pregnancies were unplanned. As such, they experience challenges and are embarrassed by the pregnancy. These are some of the reasons that contributed to the decision to opt to terminate their pregnancies. It was against this background that the researchers identified the need to conduct the study, aiming to achieve the following objectives:

- Determine the occurrences leading to the choice of termination of pregnancy amongst teenagers at Mpumalanga hospital.

- Explore the experiences to the choice of termination of pregnancy amongst teenagers at Mpumalanga hospital.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Study Design

A qualitative research method was applied in this study, which enabled the researchers to explore and describe the experiences leading to TOP amongst teenagers at Mpumalanga hospital. This research method embraced a flexible questioning approach during one-on-one interviews that enabled the researchers to gain a deeper understanding of the experiences leading to TOP amongst teenagers at Mpumalanga hospital. A phenomenological descriptive explorative qualitative research design was used. Through phenomenological design, the teenagers were able to describe their lived experiences at first hand that led them to TOP as experienced by them [19]. The descriptive research design enabled the researchers to discover the facts and gain insight into the experiences leading to TOP during the one-on-one interviews, as it was accurately described by the teenagers as they occurred in the real situation. Through exploratory design, the researchers were able to explore the circumstances which the teenagers were exposed to, which led them to TOP as well as the meaning they gave to their actions and their experiences and concerns during TOP [20]. Furthermore, clarity seeking and probing questions were asked.

2.2. Study Setting

The study was conducted in South Africa at a regional public hospital in Mpumalanga province in the Bushbuckridge Municipality under the Ehlanzeni District. The hospital is situated in the Northern part of the Ehlanzeni District towards the Limpopo province, about 70km from Hoedspruit and 100km from Mbombela (previously Nelspruit). The hospital renders level 1 and 2 health care services, including TOP. The hospital was chosen as a research site for the study because it is a regional hospital that provides services to patients referred from two district hospitals and 34 surrounding clinics. The hospital has two medical wards, one surgical ward, one orthopaedic ward, a tuberculosis ward, three wards under obstetrics and gynaecology where TOP is performed, a casualty, outpatient department, an intensive care unit, a paediatric ward, a neonatal unit, a dental unit, a pharmacy and allied health sections.

2.3. Study Population and Sampling Strategy

The eligible population consisted of all teenagers admitted to the regional public hospital in Mpumalanga province in the Bushbuckridge Municipality under the Ehlanzeni District. A non-probability, purposive sampling technique was used to select participants from the population. The justification for the purposive sampling strategy was based on the researchers' judgment to select the teenagers who have opted for TOP or have already terminated their pregnancy with the specific purpose to determine the reasons leading to TOP. A total of 30 participants aged between 13 to 19 years were selected to participate in the study. However, data saturation was reached at participant number 15. The semi-structured interviews were conducted during 1 month. The justification for including the respondents between 13 to 19 years was that it is the age group referred to as the “teen ages”. Bias was avoided during the selection of participants by using purposive sampling to select all the teenagers between ages 13 to 19 who opted for TOP and those who already terminated their pregnancy to achieve the objective of the study.

2.4. Data Collection

The researchers contacted the manager of the hospital intending to build rapport, to discuss the involvement of the participants in the study and planned dates for data collection. The researchers indicated the purpose of the study and gave the manager the approval letter from Medunsa Research Ethics Committee (MREC/HS/301/2014: PG) and the permission letter to collect data received from the Mpumalanga Provincial Department of Health office. Data was collected through one-on-one semi-structured interviews for 1 month. The interviews were conducted in Seswati and English, which is understood and spoken by the teenagers. The interviews were conducted in a private room with each interview lasting between 30 to 45 minutes. To understand the occurrences leading to CTOP amongst teenagers, one central question was asked in the same way to all the participants: “Could you please describe your experience as a teenager leading to the termination of your pregnancy?” Clarity seeking questions were asked to encourage free-flowing conversation regarding the problem studied. A voice recorder was used to capture all data collection proceedings. Field notes were also written as a backup and to provide the context of the interviews. Data collection continued until saturation was reached with 15 participants.

2.5. Data Analysis

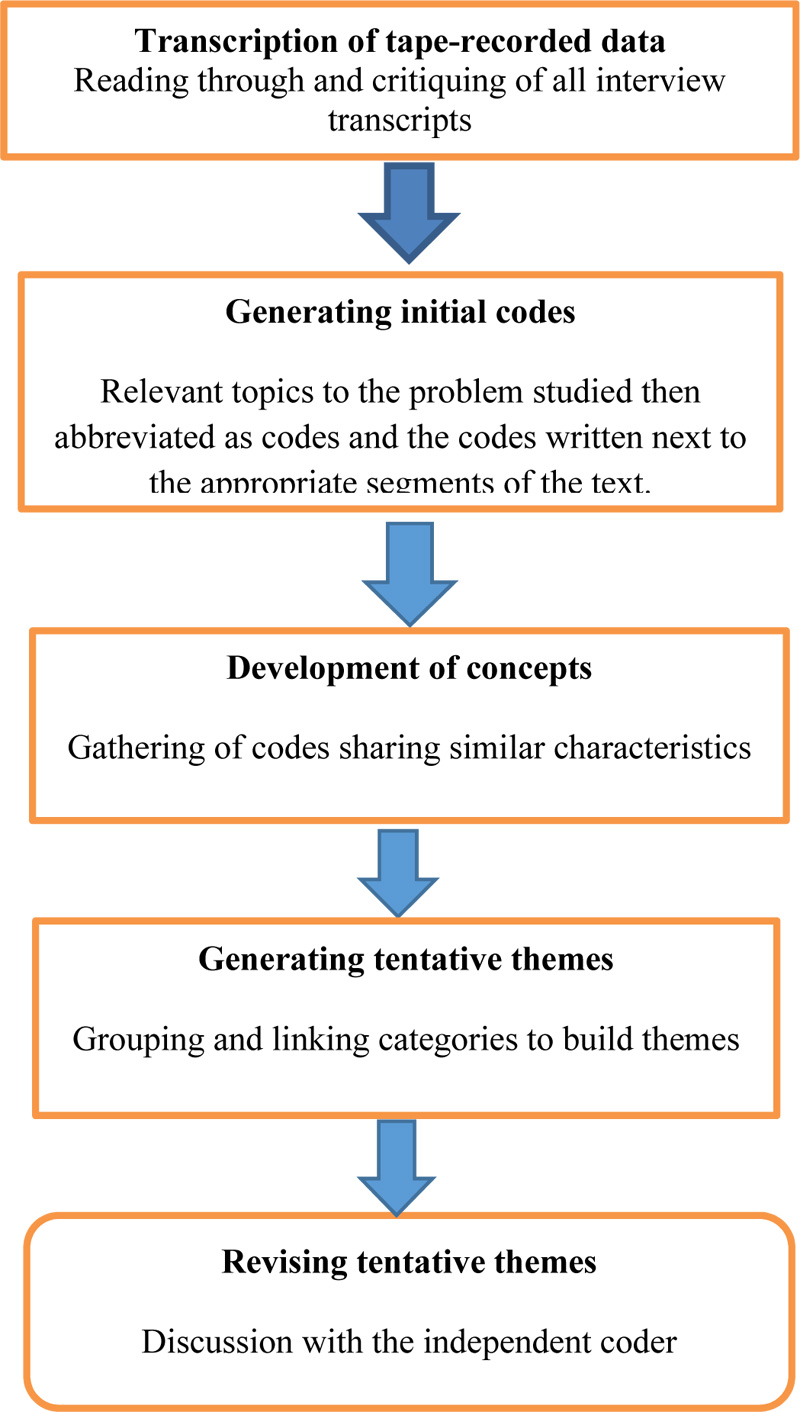

Thematic, descriptive coding technique, as cited by Creswell was used to analyse the data [21] that was collected. The primary researcher transcribed the interviews, which were verified by the project supervisor. Thereafter analysis was carried out by reading through all the interview transcripts. In order to extract the main ideas from each transcript, they were individually evaluated. The evaluation was done on all 15 transcripts. Topics were formulated from the ideas gathered and placed into columns based on their similarities - which were defined as the major topics, unique topics and leftovers. Relevant topics to the problem studied were then abbreviated as codes and the codes written next to the appropriate segments of the text. The themes and sub-themes emerged from this data analysis, the final report of these themes and sub-themes were written in columns [22]. The voice recorded data, copies of the transcribed data, and field notes were sent to an independent coder who was an experienced qualitative researcher. Thereafter a meeting was held by the research team and the supervisors where final themes and subthemes were identified and summarised. Study accuracy was enhanced through a member check of the emerging data with the participants (Fig. 1).

2.6. Credibility of the Study

The researchers ensured credibility through member checking by conducting follow-up interviews, which provided the opportunity for participants to provide additional information and to clarify errors [19]. To maintain dependability, the researcher-interviewer repeatedly listened to the tape during transcription and proofread the verbatim transcription for accuracy. Furthermore, the voice recorded data, copies of the transcribed data, and field notes were sent to an independent coder who was an experienced qualitative researcher [22]. Transferability was ensured by an explicit description of the research method that was used in this study.

3. RESULTS

Themes and sub-themes reflecting experiences leading to the Termination of Pregnancy (TOP) amongst teenagers emerged from the 15 interviews which were conducted. Four themes and sub-themes are summarised in Table 1.

The findings of the study revealed that teenagers had different experiences which led them to opt for CTOP, this emerged in the three sub-themes of this study namely: The feeling of fear and anxiety, the despair related to ending the life of the unborn baby and disclosure of the pregnancy to family members.

| Themes | Sub-Themes |

|---|---|

| 1. Circumstances leading to TOP amongst teenagers | 1.1 Feelings of fear and anxiety 1.2 Despair related to ending the life of the unborn baby. 1.3 Disclosure of pregnancy to family members |

| 2. Views related to health care professionals/service providers | 2.1 Acknowledgement of support provided by health care professionals 2.2 Provision of pre- and post-counselling following CTOP. |

| 3. The experiences of the teenagers after CTOP. | 3.1 Depression and self-blame after the procedure 3.2 Feeling of relief after CTOP. |

Sub-theme 1.1: The Feeling of Fear and Anxiety

The teenagers who opted for TOP mentioned that they experienced feelings of fear and they were also anxious about the pregnancy:

“Immediately I discovered that I was pregnant, it was a very sad and painful moment, I also started to have all the fears especially that my parents will disown me and also the anxiety of being laughed at by my friends and my neighbours, therefore, all these led me towards thinking and asking that I do abortion”.

Another participant with the same experiences indicated that:

“I was very emotional and could not cope at school, because of the pregnancy. This resulted in me becoming isolated from my peers because I was scared they will laugh at me that I am pregnant. This is an embarrassment to you as an individual when you compare yourself with your peers”.

Sub-theme 1.2: Despair Related to Ending the Life of the Unborn Baby

The findings revealed that teenagers experienced feelings of despair related to TOP because they had thoughts that they were doing wrong by thinking of ending the life of a living being. The participant who experienced depression indicated that:

“Thinking of abortion it was so sad and hurting to me, but I went to the clinic and tell the nurses that I was thinking of aborting the baby and also that it is painful for me as I feel like a murderer. The nurses indicated to me that I have signs of depression and also that it was normal. I was then referred to this hospital”.

Sub-theme 1.3: Disclosure of Pregnancy to Family Members which Led to TOP

The study findings revealed that some of the teenagers were able to disclose their pregnancy to their parents and family members; however, the reaction and the response of the family members towards the pregnancy contributed to their decision to opt for TOP. This was confirmed by the quote from the participant who said that:

“I decided to inform my mother about the pregnancy and she was very angry that I was pregnant. She even mentioned that she is raising me alone and struggling, so I don’t feel pity for her and she told me that I'm still very young and not married, I had no choice but to opt for the TOP.”

In addition, another participant said:

“I only told my older sister who scared me and tells me that if I tell our parents they will chase me away, that is when I opted for abortion because I was scared on how my parents will react”

Theme 2: Views Related to Health care Professionals’/Service Providers

The teenagers commended the care and support they received from the health care professionals during the difficulties related to TOP from the referral clinics to the hospital. Two sub-themes have emerged from this theme, namely: Acknowledgment of support provided by the health care professionals and the provision of pre and post-counselling following TOP.

Sub-theme 2.1: Acknowledgment of Support Provided by the Health Care Professionals

The teenagers who opted for TOP acknowledged the support they received from the healthcare providers. They further expressed that health care providers are playing an important role in the process of the TOP. The care is viewed as consistent and continuous. The care and support were confirmed by the participant who said:

“I felt being loved and supported by the nurses in the clinic, they gave me information and tell me to go and decide on my own, they did not judge me.”

Through probing she further said:

Even here at the hospital, they are so caring, they do not judge us, but they assist us and understand our situation and throughout our stay, they try by all means to provide the care we need at the time we need it.”

Sub-theme 2.2: Provision of Pre and Post Counselling following TOP

The healthcare providers provided continuous counselling to the teenagers who opted for TOP. This was evidenced by the participant who said:

“They provided us with pre-counselling regarding the TOP before booking us for the procedure and continuously during our stay, they continued giving support and provide us with everything we want.”

Another participant added by saying:

‘’I'm waiting for discharge but I feel better because I received the counselling even after abortion. One nurse even advised me that I must immediately use the contraceptives so that I do not fall pregnant again”

Theme 3: The Experiences of the Teenagers after TOP

The present study indicated that teenagers who had undergone TOP experienced different feelings and emotions after CTOP was performed. The following two sub-themes emerged from this theme: Depression and Self-blame after TOP and the feeling of relief after TOP.

Sub-theme 3.1: Depression and Self-blame after TOP

It was evident from the study findings that teenagers who opted for CTOP blame themselves for this and they always feel guilty about their actions. This was evident from the participant who said:

“I wish I did not fall pregnant again because the father of the baby left me for another woman and this made me sad. Emotionally I was down, after abortion. I didn't think that it will affect me like that. It was so painful and I cried a lot. I told one of my best friends who advised me to consult the doctor because I shouldn’t be depressed as this can affect mental health and my schooling.”

Another participant added by saying:

“I wish I did not listen to my boyfriend when he said he loved me and will marry me if I fell pregnant. This is the reason I opted for CTOP and this is all my fault listening to him. I should have used contraceptives and indicated to him to use condoms also”.

Sub-theme 3.2: Feeling of Relief after TOP

The participants indicated that they had feelings of relief after the termination of their pregnancy. The one participant outlined the feelings of relieve by saying:

“I felt very relieved after the termination of the pregnancy because my peers will never know I was pregnant and even my parents will never know of what I have done”.

Another participant added by saying:

“I had a feeling of being relieved, it was like a burden to me because even my boyfriend didn't want me anymore, now I am free.”

Through probing the teenager continued and said:

“I was afraid of raising a child alone, as I'm also still a child who depends on my mother's grant for living. It would have been proper to fall pregnant if I was already working like others, but for now, I couldn’t.”

4. DISCUSSION

The choice of TOP remains a controversial issue worldwide. In South Africa, the TOP Amendment Act 5(3) Act NO 92 of 1996 states that a minor as young as 12 years old do not need to have the consent of her parents to obtain an abortion. The current study aimed to determine the incidences leading to the choice of termination of pregnancy and to explore the experiences leading to the choice of termination of pregnancy amongst teenagers at Mpumalanga hospital.

The qualitative study findings revealed that several circumstances led to teenagers' decision to opt for TOP. The participants experienced mixed feelings such as the feeling of shame and embarrassment amongst their peers, within the community and also at school. Furthermore, some teenagers had a fear of being disowned by their parents and their peers, which resulted in them feeling isolated. Consistent with this finding the study conducted by Bhana, Morrell, Ngabaza, and Shefer on South African teachers' responses to teenage pregnancy and teenage mothers in schools, the study revealed that some pregnant teenagers displayed feelings of shame, embarrassment, humiliation, and fear of losing the respect of their parents [23]. In agreement with Bhana et al., Morake’s study in SA’s Limpopo Province outlined a variety of factors which led teenagers to consider a termination of pregnancy. These included poverty, the social stigma surrounding pregnancy in teenagers, or fear of their parents' reaction to premarital pregnancy, educational difficulties, fear of a broken engagement or abandonment, or a boyfriend’s denial of paternity [11]. It was further specified that the thought of termination of pregnancy amongst teenagers can be influenced by several factors such as religious beliefs, the living environment, how the teenager relates with her parents, peer group behaviour and accessibility of family planning services [24]. More importantly, the study conducted by Frederico, Michielsen, Arnaldo, and Decat indicated that in most instances the family members of the teenagers are the ones who usually influence the teenager's decision to opt for a termination of pregnancy either directly or indirectly, for instance, most parents threaten to chase them away from home [25].

The study’s findings show that the decision to terminate the pregnancy amongst teenagers was not easy, during the process, they experienced feelings of despair. The thought of wrongdoing by ending the life of a living being led to depression of some of the other participants. In a study done by Loke and Lam, it was revealed that the personal views on life influenced their decision on what to do about their pregnancy [26]. It was reported that the teenagers who opted to retain the pregnancy perceived the fetus as a living being and respected its right to live.

The study also revealed that some teenagers experienced feelings of despair and self-blame because emotionally, they felt that ending the life of a human being is wrong and they blamed themselves. On the contrary, post TOP other teenagers had a feeling of relief; they also reveal that they were coping well and they were free from the burden of an unwanted pregnancy. MacGill and Legg outlined that despite the reason behind TOP, the emotional response might differ from feelings of being happy and relieved to feelings of sadness, grieving, and regret. Different emotions might also be engendered in the situation faced by the teenager [27]. The American Pregnancy Association outlined that it is essential that different emotions experienced by women pre and post-abortion such as anger, shame, remorse or regret, loss of self-esteem, feelings of isolation and loneliness and relationship problems, be understood and recognized [28]. Additionally, from the psychologist's perspective self-blame is an ethical and socially acceptable behaviour that displays that the teenager accepts and understands the responsibility of wrongdoing. More importantly, moving forward, it helps the teenager to maintain self-integrity and honesty [27].

The health care professionals were receptive to teenagers regarding TOP and their services were applauded and recommended by the teenagers who opted for TOP, the services included pre-and post-counselling. Furthermore, the teenagers stated that the care and support they received from the health care professionals both from the referral clinic and the hospital, made them feel at ease during the abortion process. Some teenagers relayed how they were supported by the health care professionals who were not judgemental to their decision to terminate their pregnancy. In a contrary literature review study, which was done amongst health care providers in Sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia, it was revealed that health care professionals have moral, social- and gender-based uncertainties regarding the termination of pregnancy. Moreover, the uncertainties have affected their attitudes towards TOP and also affected their relationship with the pregnant woman who wishes to have an abortion [28]. In South Africa, a study by Stampler, and Flemmit, revealed that though the termination of pregnancy was legalised, most of the health care professionals are resistant to perform TOP due to moral reasons [10]. The lack of trained health care providers in public services was the main barrier for accessibility of TOP services in SA.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the study revealed that the teenagers who opted for TOP had different experiences related to TOP which affected how they coped. This was due to the support systems from family and health care providers. It is further concluded that consideration to opt for TOP is influenced by the community where a teenager lives, her relationship with the other parent and the behaviour of her peer group. Lack of a support system for teenagers during unplanned pregnancies does not only lead to feelings of despair and self-blame, but other negative health outcomes can affect teenagers, such as depression and suicidal thoughts. There is a need to support pregnant teenagers and assist them in their decision before and after TOP. Though TOP has been amended and legalised in South Africa, continuous awareness about TOP should be conducted in the communities and at schools.

LIMITATION OF THE STUDY

The study was limited to one hospital which is a weakness. Nevertheless, the selected hospital is a regional hospital receiving patients from 2 district hospitals and 34 clinics.

ETHICAL APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

Ethical clearance was sought and obtained from the University of Limpopo Medunsa Research Ethics Committee, South Africa (MREC/HS/301/2014: PG).

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

Not applicable.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Verbal and written informed consent was obtained by the researchers from the teenagers who participated in the study before data collection. The objectives of the study were outlined and also that the study will be published. Furthermore, they were assured that their identity will be protected.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

The data that support the findings of this research are available from the corresponding author [L.M] upon request.

FUNDING

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no financial or personal relationship that has inappropriately influenced them in writing the article.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank the Mpumalanga Department of Health for giving permission to conduct the study. All teenagers who participated in the study are acknowledged to in providing information which was relevant to the problem studied.

Mothiba TM was responsible for the conceptualisation of the research study, drafting and finalisation of the article; Mabaso K, was responsible for data collection, design and analysis of the research study; Muthelo L drafted, conceptualised and wrote up the article.