All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Public Attitudes in Asia Toward Stuttering: A Scoping Review

Abstract

Background/Objective:

Limited information is available about public attitudes towards stuttering across Asia. This review considers the key factors and approaches used to measure public attitudes towards stuttering across Asia that have previously been published in order to identify potential research gaps.

Methods:

A scoping review was conducted using the Arksey and O’Malley’s (2005) framework.

Results:

A total of nine relevant articles, published between 2001 to 2019, were selected for review. Most of the studies used the Public Opinion Survey of Human Attributes (POSHA) as a survey tool. This review yielded studies from Turkey, Kuwait, China/Hong Kong, and Japan. Asian public attitudes towards stuttering were less positive in general, except in Kuwait.

Conclusion:

Given that limited research has focused on examining the attitudes towards stuttering among the general public in the Asian region, we call for international collaboration to increase research about public attitudes. Such data could assist speech-language pathologists in developing awareness campaigns for better intervention and increased acceptance of individuals who stutter.

1. INTRODUCTION

Stuttering is a speech disorder characterized by repetitions of syllables, part or whole words, or phrases, prolongations of sounds, or blocking of sounds, as well as associated negative emotional responses, such as embarrassment and anxiety [1]. The incidence of stuttering is reported to range between 5% to 15% [2-4]. Prevalence studies have shown that stuttering occurs in approximately 1% to 1.5% of the population occurring more commonly among males than females by a ratio of 3:1 [5]. In the USA, the prevalence rate of stuttering is 2.52% in children aged 2 to 5 years old [6]. Meanwhile, in Belgium, the overall prevalence of stuttering in the regular and special education school population was 0.58% and 2.28%, respectively [7].

A study conducted in Bangalore, India, found 1.5% of stuttering in urban middle-class areas, urban slum areas, and rural areas [8]. In Iran, it was found that 1.13% of the bilingual student population stuttered [9, 10]. The similarities in prevalence data reported for these geographical areas, including 0.82% in Japan [11] to those reported in North America, Europe, and Australia, led us to deduce that the incidence of stuttering is generally similar across Western and Asian regions.

Knowing more about the public views about stuttering and the social environment of those who stutter could improve the lives of these people who stutter by leading to better public education and improved public reactions of stuttering events, reducing the impact of the condition and making it less debilitating [12]. Furthermore, in order to prepare public education campaigns, it is necessary to first understand current levels of public knowledge about stuttering to identify ways to create a more accepting society [13]. Identifying public opinions about various human conditions or attributes around the world could affect the quality of life for people who stutter and experience other stigmatized conditions.

1.1. Cultural Differences on Public Attitudes Towards Stuttering

Asian and Western countries might have different views and attitudes towards stuttering, as “crucial miscommunications” can result from cultural variations between communication partners [14]. In particular, cultural differences might contribute to different views and attitudes toward stuttering [15]. Using the Public Opinion Survey of Human Attributes POSHA [16], public attitudes have been shown to be more positive (i.e., less stigmatizing and less ostracizing) in Western cultures (e.g., North America, Western Europe, Australia) than in other parts of the world [17-20], although these results were inconsistent across studies [12]. An unpublished study [21] indicated that over 50% of individuals of Asian ethnicity (i.e., Asian individuals who live in the United States but were not born there) rejected the SLP services, while 43% had no exposure to people who stutter and showed no familiarity with speech-language pathologists. The variety in these backgrounds could influence the acceptance and perceptions of the public towards stuttering.

Clients from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds may experience difficulties in discussing personal matters with speech-language-pathologists (SLPs), particularly at the beginning of a relationship. Such differences may be increased if clients and SLPs differ in culture, gender, or age [22]. Asian Indians were found to believe that it is appropriate to hide a child with a disability from public view, because the disability is a reflection of the entire family [23]. In Greek, Arab, and Chinese cultures, people were found to have reduced expectations for children with disabilities to attend school, play with neighbourhood children, and be included in family activities [23]. In the Chinese culture, the sense of “loss of face” (incompletely translated to English as reputation or honor) occurs when certain events disrupt the harmony with nature and other people. This is a unique religious-cultural issue that has direct relevance to stuttering [24]. The concept of Face, which has been influenced by thousands of years of Chinese culture, threatens the personal psychological well-being and the social order when certain behaviours or disorders disrupt that harmony [25]. Even with the knowledge of these factors, however, an understanding of the attitudes of Asian cultures towards stuttering is incomplete, so further information is needed.

1.2. Aim of This Scoping Review

The purposes of this scoping review were (a) to consider attitudes towards stuttering among the public across Asia and (b) to find gaps in the published literature in order to encourage future research. The study involved identifying currently available studies that measure attitudes towards stuttering among the public across Asia.

2. METHODS

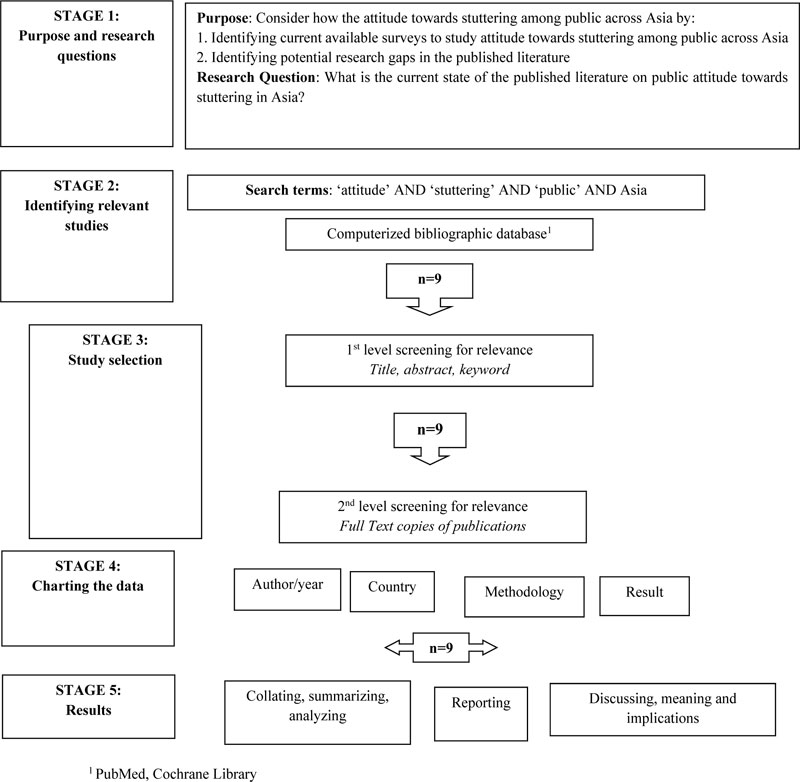

As suggested by Arksey & O’Malley (2005) [26], scoping reviews are useful for mapping an area of study which has not previously been reviewed comprehensively. This is the case for the study of public attitudes toward stuttering in Asia. Thus, Arksey and O’Malley’s (2005) framework was used as a guideline for this scoping review [26]. The following steps were included: 1) identification of the research question to be addressed; 2) identification of studies relevant to the research question; 3) selection of studies included in the review; 4) charting of information and data within the included studies; and 5) collating, summarizing, and reporting the results Fig. (1). The five stages of this scoping review are detailed as follows:

2.1. Identifying the Research Question

This scoping review considered the key approaches and factors associated with public attitudes among Asians in academic literature and identified potential gaps in the research. The central question guiding this review was: “What is the current state of the published literature on public attitude towards stuttering in Asia?” Thinking about future improvements for the quality of life among individuals who stutter and knowing that there are many considerations that could influence the management and treatment of this disorder worldwide, it is essential to know the published documentation for research about this topic. The desire to know more about the factors that influence public attitudes towards stuttering brings us to this research question. The goal is for this review to benefit individuals who stutter and their families as well as the clinicians who serve them, specifically in Asia, bearing in mind that research on this area is still limited in Asia compared to Western countries.

2.2. Identifying Relevant Studies

Prior to beginning the review, the search strategy was pilot-tested to establish its efficacy. Only English versions of articles were included in this review. The following search terms were used: “attitude” AND “stuttering” AND “public” AND “Asia.” These terms were selected after consultation with experts in the field and based on the results from our pilot-tested search. The following electronic databases were searched: Cochrane Library and MedLine (PubMed). These databases were chosen because they index a broad range of healthcare disciplines and are free to access. The phrase search in the Cochrane library database returned “no result.” A search using MedLine (PubMed) resulted in nine studies.

2.3. Study Selection

The inclusion criteria for this review were: a) published studies were in the Asian countries, and b) findings focused on attitudes toward stuttering. In the initial search of computerized bibliographic databases, nine results were retrieved. The first level of screening involved reviewing the title of articles. The nine articles were selected and included in the second level of screening. The abstracts and full texts of the nine articles were printed out, reviewed, and summarized.

2.4. Charting the Data

All nine articles were reviewed using the following organizational categories: authors, year of publication, country of origin, methodology, and results Table (1).

| Author/year | Country | Methodology | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Al-khaledi et al. [38] (2009) | Kuwait |

Subject sample: 424 (37%RR) Arab parents at preschool and school age of 18 schools across the 6 governorates. A survey POSHA-E |

General public is empathetic and sensitive towards PWS based on these result: - Age: significant difference in the score which is younger, more negative opinion (M=-.72, S.D.= 1.80) Gender: 43% male positive attitude towards PWS compared to females. Education level: Higher education (83%) more positive than lower education. Most parents seem aware of the disorders, their knowledge appeared to be generally limited with 33% they knew “a little” about stuttering. The overall majority had a positive attitude but held stereotypical beliefs about PWS (“fear and shy” and “should not work in the influential job”) but some inconsistency with the responses to statement. |

| Abdalla & Louis [47] (2012) | Kuwait |

Subject sample: 262 in service 209 pre service Teachers A survey used POSHA-S (Arabic version) |

31% teachers knew PWS and were sensitive in interactions. 15% of teachers believed virus or disease could lead stuttering and showed that they misinformed about the causes of stuttering and held stereotypical views on PWS. Some demonstrated that they were sensitive to PWS. Knowledge- reasonable Belief - unsubstantiated Attitude-3/4 teacher positive |

| Ozdemir et al. [32] (2011a) | Turkey |

Subject sample: 70.1% out of 150 responded 66.7% RR PROB1 74.3% RR PROB2 POSHA-S (Turkish version) Convenience sampling |

CONV vs PROB 1 PROB 2 Significant differences between convenience sampling (CONV) and either PROB1 or PROB2. |

| Ozdemir et al. [36] (2011b) | Turkey |

Subject sample: 2 sets (50 each in Eskesehir, Turkey) -children -parent, -grandparent/adult relatives - neighbour Cluster probability sampling scheme 3 stages POSHA-S (Turkish version) |

Attitudes toward stuttering, as measured by the POSHA-S, were very similar between two replicates of a school-based, representative probability sampling scheme. Dissimilar attitude toward obesity and mental illness. Attitudes toward stuttering were estimated less positive (negative) than attitude towards a wide range of samples (world). |

| St. Louis et al. [16] (2005) | Brazil, Bulgaria and Turkey |

Subject sample: 3 group adults according place of residence & survey language variable - Brazil (South America) - Bulgaria (Eastern Europe) Turkey (Middle East Asia) Pilot study Compare selected results POSHA |

Some attitudes different among respondents. -Brazil: stuttering is regarded as a serious handicap and the public has a great deal of misinformation and confusion about stuttering. -Bulgaria: some positive attitudes toward people with stuttering but also some misinformation about stuttering. -Turkey: religion and culture were influential factors in public opinion about stuttering. |

| Weidner et al. [42] (2017) | United State of America (USA) and Turkey |

Subject sample: 28 US + 31 non stuttering pre-schoolers Non-exp, comparative study POSHA-S/Child Watch video 2 stuttering Avatar Answer oral questions |

US children had more exposure to experience with stuttering than Turkey. Generally, negative stuttering attitudes in both countries. Attitude both similar positive: traits and personality negative: stuttering children’s potential |

| Iimura et al. [13] (2018) | Japan |

Subject sample: 303 respondents 156 males, 147 females 3 cities - Tokyo, Nagoya + Tsukuba Street sampling, survey Japanese Version (Van Borsel et al., 1999) |

Half of 303 respondents heard and met stutterer, but the majority lacked (limited) general knowledge of stuttering-prevalence estimated to high and half accurately reported the age of onset. Respondents tended to misunderstand the stuttering and their knowledge differed between age, gender, education level. If older, females and higher education-more knowledge - Different & similar previous study: Belgium, China + Brazil |

| Ip et al. [36] (2012) | Hong Kong and Mainland China |

Subject sample: 282 out of 431 China 182 out of 230 HK Convenience sampling POSHA-S |

Females more than males (both) Working more than students (Mainland) compared with HK. HK better attitude of “learning or habit” Mainland better attitude of “act of God”. Stuttering attitudes far more similar between HK and Mainland China. |

| Ming et al. [33] (2001) | Shanghai, China |

Subject sample: 10 out of 12 district in Shanghai 1968 respondents (2 groups - below 21y/o vs 21-55y/o) Use questionnaire by Van Borsel (1999) On street sampling |

Knowledge still limited (59% knew a stutterer; 40.3% accurate prevalence, 60.5% correctly answer age onset) although most of the respondents (85.4%) have met or heard a stutterer at one time. 98% convinced stuttering also occurs in other culture. Older (8.4%) indicated intelligence of stutterer higher than non-stutterer while younger found it equal (87.9%). Not hereditary (76.8%) |

2.5. Collating, Summarizing and Analysing the Data

In this stage, data extraction was done by developing tables and themes for summarizing our findings. This was based on the recommendations by Colquhoun et al. [27] for ensuring consistency in labelling and defining both descriptive and quantitative summaries. The discussion on findings related to the study’s purpose and implications for future research is summarized.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Organization of Articles by Year and Country of Origin

There were nine studies resulted from this scoping review. Two of the nine articles in this review were published between 2011 and 2012, and one article each was from the years 2001, 2005, 2009, 2017, and 2018. This indicates that there are few studies available on public attitudes towards stuttering in Asia. Of these, only four countries were represented in this review. The majority of articles involved Turkey (n=4, 44%), followed by China (n=2, 22%) and Kuwait (n=2, 22%); only one study (11%) involved Japan.

3.2. Distribution by Type of Methodology and Research Materials

Of the selected nine articles, 78% (n=7) utilized a qualitative survey and 22% (n=2) used a comparative study design. The use of survey methods may be due to surveys being a cost-effective, less time-consuming method of gathering information with high response rates [28]. The two studies using the comparative study design used questionnaires by Van Borsel, Verniers, and Bouvry [29] while the other 5 survey studies utilized the Public Opinion Survey Human Attributes (POSHA) questionnaire.

3.3. The Survey Tools/ Instrumental of Studies

All of the papers reviewed used survey methods to understand the knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs of the public towards stuttering. As noted, seven of these studies used the POSHA and two studies used Von Borsel [29] as their assessment tool. The POSHA is a comprehensive questionnaire that provides a reliable, valid, and translatable measure of public attitudes toward stuttering [30]. The Von Borsel [29] survey only investigates the public’s level of awareness and knowledge of stuttering.

3.4. Similarities and Difference of Awareness, Knowledge, Attitudes, and Belief Towards Stuttering in Asia

Two studies were conducted in Middle-Eastern Asian countries (Table 2). In Turkey, the public knowledge and opinions about stuttering were found to be similar to that in other regions among children, parents, grandparents/adult relatives, and neighbours [31]. These attitudes towards stuttering are generally less positive than attitudes seen in a wide range of populations in other areas around the world [12], but they are remarkably similar across subgroups (children, parents, grandparent/adult relatives, and neighbours). The beliefs about stuttering among Turkish respondents were uniformly low for children (1% and 13%), parents (5% and 6%), grandparents/adult relatives (6% and 3%) and neighbours (6% and 0%). For example, respondents indicated their belief that people who stutter are “nervous,” “excitable,” “shy,” or “fearful.” All of these characteristics are closely related to common “stuttering stereotypes” [32]. The findings among pre-school children in Turkey were similar to those for pre-school children from the USA, reflecting attitudes towards stuttering that are generally negative. This is due, in part, to preschool children expressing little knowledge about stuttering and a limited understanding of how to react appropriately to their stuttering peers. Meanwhile, the overall attitudes towards stuttering in Kuwait were positive, although knowledge about stuttering among Kuwaitis was limited (e.g., only 33% knew “a little” about stuttering). Parents in Kuwait were aware of stuttering, but they still held stereotypical beliefs about the disorders. Moreover, teachers also reported positive attitudes towards stuttering.

| Countries | n=9 | Awareness | Knowledge | Attitudes | Belief |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turkey | 4 | Yes | Little (Children) | Less positive (public) Negative (children) |

Low |

| Kuwait | 2 | Yes | Yes (Teachers) Limited (Parent) |

Positive (parent) Positive (teacher) |

Unsubstantiated/stereotypical |

| China/ Hong Kong | 2 | Yes | Limited (some aspects) | Unique (negative/positive) | Negative |

| Japan | 1 | Limited | Limited/lack | Negative | Low |

In terms of the East-Asian region, only studies from China/Hong Kong and Japan were found. The attitudes towards stuttering in China were found to be more negative than average compared to the POSHA-S database from around the world [33]. The limited research and anecdotal evidence available on public attitudes toward stuttering in China suggest that Chinese individuals might hold more negative beliefs and identify harsher self-reactions to stuttering than people in Western societies. Overall knowledge among this population was still limited, although awareness of the impairment exists. Attitudes about stuttering in Hong Kong (22.2%) were more positive than in China (19.6%). There was limited awareness and knowledge about stuttering among the public in Japan. For example, the prevalence was generally estimated too high, and only half of the respondents accurately reported the average age of onset. The public in Japan also believed that stuttering cannot be treated due to people who stutter, choosing to accept their stuttering and living with it [34].

3.5. Cultural and Religious Differences

Public attitudes in Western countries (North America, Western Europe, and Australia) were typically positive when compared with non-western countries (Middle East, South America, Asia and Africa) [12]. In this review, only Kuwait reflected similarities to Western countries in attitudes towards stuttering. Other Asian countries (Turkey, China/Hong Kong, and Japan) held a more negative attitude towards stuttering. [13, 31, 35, 36]. The negative attitudes toward stuttering in these countries indicated low acceptances of stuttering behaviors. The Arabic and East Asia culture have many beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors that are different from Western cultures. This reflects the reality of people’s attitudes and perceptions of physical handicaps and disorders being influenced by cultural and religious customs and beliefs [37].

3.6. Age, Gender and Education Level

Age, gender, and educational factors have been shown to influence public attitudes towards stuttering. In general, younger age group tends to report more negative opinions than the older age group [33, 38, 39]. For example, the younger age group (39 years old and under) reported more negative opinions in a study of attitudes in Kuwait. This could be due to cultural acceptance, experience with the people who stutter, or updated knowledge of options, solutions, and help for coping with stuttering.

In terms of gender, men showed more positive attitudes than women, where 43% of the males in Kuwait felt that they would not look away from the person who stutters while they were talking [38]. In China, men were more knowledgeable (71%) towards stuttering and reported a more realistic view towards stuttering, while women had a more optimistic view regarding the possible outcomes of treatment. The influence of gender on attitudes towards stuttering was not included in studies conducted in Turkey. In China, males in the family played the central role in decision-making for treatment-seeking rather than females, who are culturally less outspoken but remain more hopeful.

In Kuwait, those who have a higher education level reported more positive attitudes towards stuttering. Similar results were reported in Japan, where older adults, females, and respondents with higher education levels reported more positive attitudes towards stuttering. In Turkey, families and circles of friends were determining indicators of attitudes toward stuttering. This could be due to the broadening of perspectives through education or travel or to personal experiences with people who stutter. This finding is similar to findings from the USA and Poland, which revealed that the educational level is a factor for attitudes towards stuttering. Speech-language pathology students held more positive attitudes than non-SLP students in both countries, and graduate students in the USA also held more positive attitudes than undergraduate students [39].

4. DISCUSSION

The scoping review sought to describe the currently available literature related to public attitudes toward stuttering in Asia. In line with Arksey and O’Malley’s framework (2005) [26], we intend to provide a descriptive account of the current attitudes and potential factors that contribute to more positive attitudes towards stuttering. This is essential for developing programs for improving public education and attitudes. The quality of life of people who stutter will be enhanced if factors that affect the experience of stuttering can be identified and, ultimately, improved. Boyle [40] found that the self-esteem, self-efficacy, and life satisfaction of people who stutter are related to the level of stigma agreement and awareness. Features of the cultures and religions in a country could influence the stigmatization and beliefs about stuttering. It also could affect how people who stutter face their anxiety about speaking in public situations. It is essential for speech-language pathologists to be aware of potential cultural and religious influence attitudes towards speech disorders, including stuttering. Such awareness could reduce the culturally driven conflicts between clinicians and clients [41] and help to improve the use of helpful counselling techniques by clinicians to increase efficacy in treating people who stutter from different cultural backgrounds [21]. This scoping review can, therefore, help to educate professionals (SLPs, teachers, and counsellors), as well as individuals within the environment of the person who stutters (family, relatives, peers, and neighbours), in order to improve understanding of the condition.

Our scoping review intended to explore attitudes about stuttering in Asia. Due to more research being conducted in and available from Western countries, comparisons were also made between East and West. As a result, universal trends, with some cultural variation and progression in attitudes about stuttering, were noted regardless of geography. Negative attitudes about preschool stuttering reveal a lack of understanding about the causes of stuttering and its early development in young children [42]. The causes of these negative attitudes may differ depending on cultural factors, such as religion or traditional beliefs, but all reflect the lack of current knowledge and result in the young child and family receiving appropriate services. Improved education has a major effect on attitudes, and this can lead to better therapy options. Even though some research was conducted using convenience sampling, involving opinions from university students, the fact remains that accurate information about stuttering can result in improvements in public attitudes toward the disorder.

Gender differences in attitudes might also be linked to the amount of information the person has about stuttering. When gender was taken into consideration, as was the case in this investigation, it was clearly found that males perceived stuttering with more negativity when compared to females [43]. Culturally in China, females are viewed as more hopeful, while males are viewed as more realistic. Females held less outspoken ideas about action, because, in a Chinese family, men are viewed as decision-makers due to the Chinese Family planning policy, in which each parent or caregiver wants the best for the single child [33]. However, females are more likely to spend more time with children and take them for clinical services. From these experiences, females may gain more correct information, which positively shapes her attitudes. These differences in gender lead to more possible insights about family influences. As stuttering often runs in families [44], older family members may have more understanding and positive attitudes due to increased perspective and knowledge gained over years of experience with stuttering. Moreover, the impact of the amount of family collaboration again reflects the impact of education; the more the family is educated about stuttering, the more positive the attitudes toward and support for the person who stutters.

For East or West, the overall gains in positive attitudes about stuttering are education, and, through education, attitudes can change. Some Asian countries are still categorized as underdeveloped compared to Western countries, which have moved faster forward in technologies and infrastructure development. For instance, in China, the disparity between education and health services is very large [45]. This may be related to the fact that public attitudes towards stuttering are less positive and that stigmatization and discrimination still exist. Three studies found differences between Belgium, China, and Brazil on public attitudes toward stuttering [7, 29, 36]. These studies found that laypeople tended to report a lack of basic knowledge of stuttering. Given that similar prevalence rates were reported across developed countries, we expect that similar prevalence rates also occur in underdeveloped countries in the Asia region. Since countries in Asia shared a similar culture, language, beliefs, religions, healthcare delivery system, we believe that public attitude towards stuttering could be different than those reported in the Western countries. For this reason, further research is warranted.

5. LIMITATIONS

This review summarized the public attitudes toward stuttering that was conducted in the Asia region. It is important to note that most of the studies included in this review are not limited to the Asia region, but also compared the attitudes between the West and Asia regions. This scoping review only included English versions of articles. In addition, no follow-up studies have been conducted to determine whether these attitudes have changed over time.

6. RECOMMENDATIONS AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Based on our scoping review, limited research has focused on examining the attitudes towards stuttering among the general public in regions of Asia. The following research gaps were identified:

- There are still no studies available in exploring public attitudes toward stuttering in the region of Southeast Asia (i.e., Malaysia, Thailand, Indonesia). Most of the studies in this scoping review were completed in Middle East Asia (Turkey and Kuwait) and East Asia (China/Hong Kong and Japan), although speech-language pathologists have been practicing in Southeast Asia for over 30 years. There is a need to increase research on public attitudes towards stuttering in Asia and make comparisons across countries to understand the factors that contribute to different attitudes. Such data could assist speech-language pathologists in developing awareness of educational programs to improve intervention for people who stutter.

- A gap still exists in the literature since studies tend to focus on the closed-ended survey that was adapted from Western countries, with validation issues arising as a result. Future studies should include open-ended questions to gather a broader picture and deeper understanding of stuttering perception and management in Asia. Cheng [45] mentioned that research on speech-language pathology is not well-organized and information is not easily retrievable in China and Hong Kong.

- We call upon experts in stuttering to collaborate to conduct further research about public attitudes and opinions about stuttering across cultures and regions.

- We further call upon experts in stuttering to collaborate to develop culturally-appropriate educational programs for obstetricians, government health services, schools, public awareness campaigns, etc., and support programs for people who stutter and their families. After the implementation of these programs, follow-up studies to measure their impact should be conducted.

CONCLUSION

Given that limited research has focused on examining the attitudes towards stuttering among the general public in the Asian region, we call for international collaboration to increase research about public attitudes. Such data could assist speech-language pathologists in developing awareness campaigns for better intervention for and increased acceptance of individuals who stutter.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable.

FUNDING

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank my main supervisor and co-supervisor, for her expert advice and encouragement.