All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Risk Factors for Gender-Based Violence among Female Students of Gonder Teacher’ Training College, Gonder, Northwest Ethiopia: A Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

Background:

Violence against women is the world's most prevalent, pervasive and enduring problem. Sexual violence appears to be particularly great among adolescent girls of Sub-Saharan African countries, including Ethiopia.

Methods:

A cross-sectional survey was conducted from January to February 2018, and 322 participants were selected via a stratified sampling technique. Data were entered using Epi-data version 3.1 and exported to SPSS version 21 for analysis, then bivariate and multivariate logistic regression was employed to see statistically significant factors.

Results:

Lifetime prevalence of Gender-based violence was found to be 35.1% (95% CI: 29.9 - 40.3). Risk factors significantly associated with sexual violence were living alone (AOR = 4.3 95% CI: 1.03, 18.09), having two or more number of sexual partner in life (AOR = 11.5 95% CI: 2.80, 47.16), lack of open discussion between parents and daughters about reproductive health issues (AOR= 5.05 95% CI: 1.37, 18.55), being third year student 9.06(1.96, 41.94), strict parenting style over the girls behavior (AOR = 3.4 (1.04,10.72), alcohol consumption (AOR = 8.3 95% CI: 2.57, 27.00), use of khat (AOR = 11.05 95% CI: 3.53, 34.60), and monthly financial support to the girls from family (AOR= 0.1, 95% CI: (0.03, 0.73).

Conclusion:

The prevalence of Gender-based violence among female college students in Gonder town was high. Attention should be paid to the reduction of the prevalence and those risk factors of Gender-based violence.

1. INTRODUCTION

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), Sexual and Gender-Based Violence (SGBV) refers to any act that is perpetrated against a person’s will and is based on gender norms and unequal power relationships [1]. Violence against women is the world's most prevalent, pervasive, and systematic problem. It is a universal scourge on women and their families that affects every society with no geographical boundaries, culture or wealth [2]. Worldwide, one in three women will be physically or sexually harmed, and one in five will experience rape or attempted rape in their lifetime [3].

In developing countries, gender-based violence is a serious problem, as the rate of violence is high and takes place in the context where the risk of HIV is high [4]. There have been reports of gender-based violence in educational settings worldwide [4].

The risk of experiencing gender-based violence appears to be particularly high among adolescent girls of Sub-Saharan Africa [2]. In Sub-Saharan African countries, the prevalence of forced first sexual intercourse among adolescent girls aged 12-19 years ranges from 15 to 38% [2, 5].

A study has shown that the prevalence of intimate partner violence and gender-based violence against women is high [6]. A recent study conducted in south-central Ethiopia reported that 49% and 59% of women were physically and sexually abused by their partners at some point in their life, respectively [6].

World Health Organization and other stakeholders are fighting for the rights of women to be reproductively and sexually healthy. However, this goal remains a dream to women as their sexual rights are dishonored. It is a cause for concern to note that gender-based violence is increasing as in Zimbabwe, an average increase of 78% in the reported cases at three institutions over the 2 years, 2009 and 2010 have been observed [7].

Gender-Based Violence (GBV) is widely recognized as an important public health problem, both because of the acute morbidity and mortality associated with assault and because of its longer-term impact on women’s health, including chronic pain, gynecologic problems, sexually transmitted diseases, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and suicide [8].

In Africa, especially in Ethiopia, like any other third world country, scientifically documented information regarding gender-based violence is scarce. In general, evidence related to gender-based violence in our country, especially in college setup, is scarce. Studies related to gender-based violence had not been conducted in the study area. Thus, these studies have assessed the prevalence and associated factors of Gender-based violence.

2. METHODS AND MATERIALS

2.1. Study Design and Setting

An institution-based cross-sectional study was conducted at Gonder Teachers’ Training College (GTTC), in Gonder City, northwest Ethiopia. GTTC is one of several regional Teachers’ Training Colleges in Ethiopia established specifically to yield competent teachers for primary schools (grades 1-8). Data were collected from January to February 2018.

2.2. Participants

There were a total of 1268 regular female students registered for the academic year of 2018 in the college. A total of 322 GTTC college female students were involved in the study. The stratified random sampling method was employed, where each year of study was considered stratum. The year of the study was used in the sampling process for the selection of the study subjects. We excluded students with visual impairment, as they couldnot complete the self-administered questionnaire, and extension students.

2.3. Measurements

The dependent variable was gender-based violence ” (it includes rape and harassment in their lifetime). The independent variable included socio-demographic characteristics, such as age, marital status, place of origin, income, religion, ethnicity, living condition, number of sexual partners in their life, substance use like chat, alcohol, and other drugs (shisha and marijuana); Family backgrounds like income, educational status, parenting style, intimacy and living condition.

2.4. Data Collection Procedure and Instrument

A structured self-administered questionnaire was used. Gender-based violence was assessed using a sexual abuse history questionnaire, which has 6 items. A total score ranging between 0-6 to measure Gender-based violence and the cut of the score has > 1; it has sensitivity and specificity 88% and 91%, respectively [9]. Alcohol misuse was assessed using CAGE, which has 4 items. A total score ranging between 0-4 to screen for alcohol dependence and abuse. The cut of the score has > 2; it has sensitivity and specificity (0.71 and 0.90, respectively [10]. The questionnaire was translated into the Amharic language, and then back-translation was done by another expert to check the consistency of meanings. Data were collected by four BSc health workers after trained them. The questionnaire was pre-tested on 5% of female students' in another college, which is not included in the study before the actual study. The data collectors were trained on the data collection tools and data collection procedures. To check for completeness of the collected data,we did regular supervision of the data collection process, like and checked the collected data at the end of each data collection day.

2.5. Data Processing and Analysis

The quantitative data were entered into Epi-data version 3.1 and then exported to SPSS version 21 for analysis. The data were presented in tables and figures. We did bivariate logistic regression analysis to see the association between explanatory and outcome variables. To control the effect of confounding factors and to get independently associated variables, each variable that has a p-value of < 0.25 in the bivariate analysis was entered into a backward stepwise multiple logistic regression model. In multiple analyses, associations with p-values < 0.05 in Wald's test model were considered to be statistically significant. Finally, the result was displayed using figures and tables.

2.6. Ethical Considerations

Ethical approval was received from the institutional review board of Tseda Health Science College. Verbal consent was obtained from the study participants. The participants’ confidentiality was ensured, and their identity was not revealed. The data given by the participants was used only for research purposes.

| Characters | Frequency (n=299) | Percent (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 15-19 20-24 25-29 30-34 |

159 92 35 13 |

53.2 30.8 11.7 4.3 |

| Current living condition | Living alone Living with parents Living with husband/boy friend Living with a female friend Living with relatives |

124 29 27 104 15 |

41.5 9.7 9 34.8 5 |

| Marital status of the respondent | Single married divorced widowed separated |

187 33 56 12 11 |

62.5 11 18.7 4 3.7 |

| Ethnicity | Amhara Oromo Gurage Tigre |

8 262 22 7 |

2.7 87.6 7.4 2.3 |

| Year of study | First Second Third |

99 101 99 |

33.1 33.8 33.1 |

| Place of origin | Urban Rural |

74 225 |

24.7 75.3 |

| Source of financial support | Parents relative husband boy friend others |

242 20 22 11 4 |

80.9 6.7 7.4 3.7 1.3 |

| The frequency of financial support | Monthly every semester once in year not at all others |

88 131 32 39 9 |

29.4 43.8 10.7 13 3 |

| Income per year in ETB | 0-549 550-1199 1200-1999 >=2000 |

73 76 42 108 |

24.4 25.4 14 36.1 |

| Having boy friend | Yes No |

95 160 |

37.3 53.5 |

3. RESULTS

3.1. Socio-Demographic Characteristics of Study Subjects

From 322 students, complete data were obtained from 299, making a response rate of 92.9%. The remaining 7.1% were incomplete, while others did not return to the data collectors at all. Among the total respondent, almost all students from each year of studies were equally represented, i.e., 2nd year (33.8%), 1st and 3rd-year students 33.1% each (Table 1).

The mean age of the respondents was 21 years old,(standard deviation (SD) ± 3.683). Most of the participants were Ethiopian Orthodox Christians; 90 (30.1%). Most of the particpants were Oromos; 262 (87.6%). The majority of the participants were single;187(62.5%) While 225 (75.3%) of them were born and brought up in rural areas. Most of the students (80.9%) were supported by their families. Likewise, most of the respondents were receiving money on a semester basis (43.8%). Most of 108 (36.1%) having more than or equal to 2000 annual income in ETB. Among the total respondents, the majority of 116(38.8%) of them had only one sexual partner in their lifetime (Table 1).

3.2. Parental Characteristics of Study Participant’s

One hundred twenty-three (41.1%) of the respondents had a habit of discussing reproductive health issues with their parents. Most of the respondents (58.9%) had literate mothers and 76.9% of the respondents had literate fathers . The mean family annual income of the respondents was 36,395.57 ± 61,547.6 birr, with the range from 1,980 to 720,000.00 birr. The leading parenting style was reported to be strict, i.e, 40 (13.4%) (Table 2).

3.3. Forms of Gender-based Violence and Sexual Related History of the Respondent

Among the total respondents, the majority;116(38.8%) of them have experienced only one sexual partner in their lifetime. Ninety-four (31.4%) of students had no sexual partner in their lifetime. For discussing reproductive health with parents, 123(41.1%) discuss their sexual issues with their parents. Mechanisms used by the perpetrator to have forced sex are bing physical 7 (2.3%), threaten with a knife and gun 10 (3.3%), threaten with words 33(11.0%), by income support 7 (2.3%), due to drunken 13 (4.3%), to pass the exam/for mark 9 (3%) and by giving drugs 3 (1.0%).

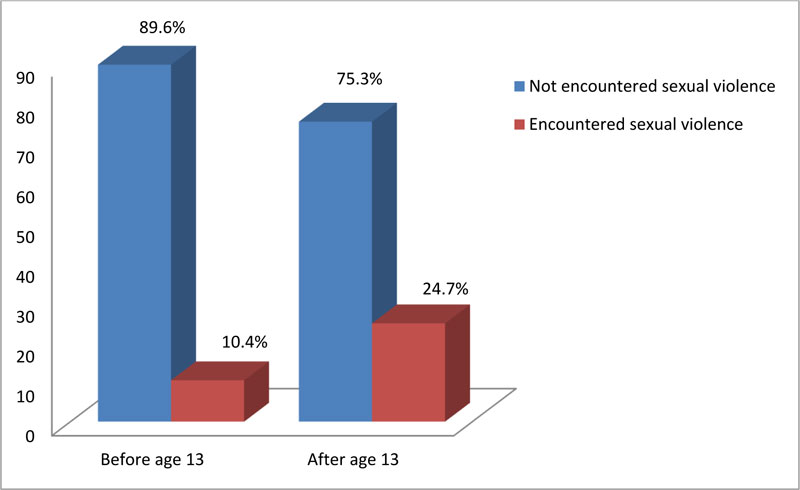

From a total of 105 respondents who encountered Gender-based violence majority, 15 (5%) ever exposed to the sex organs of the perpetrator before 13 years, while 37 (12.4%) were forced to have sex after age 13. The majority (24.7%) of participants reported that they had been sexually violated after the age of 13 (Table 3 & Fig. 1).

| Character | Frequency (n=299) | Percent (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parents living condition | Living together divorced/separated only mother alive only father alive both of them not alive |

234 21 24 10 10 |

78.3 7.0 8.0 3.3 3.3 |

| Educational status of a father | Illiterate 1-4_grade 5-8_grade 9-12_grade above_12 grade I don't know |

40 75 71 44 40 29 |

13.4 25.1 23.7 14.7 13.4 9.7 |

| Educational status of a mother | Illiterate 1-4 grade 5-8 grade 9-12 grade Above 12 I don't know |

99 92 54 17 13 24 |

33.1 30.8 18.1 5.7 4.3 8.0 |

| Family annual income in ETB | 0-13199 13200-23999 24000-35999 >=36000 |

69 61 84 85 |

23.1 20.4 28.1 28.4 |

| Parenting style | Restrict Average Loose |

157 102 40 |

52.5 34.1 13.4 |

| Character | Number (%) Before 13 year |

Number (%) After 13year |

Number (%) Life time sexual violence |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Forms of sexual violence Ever exposed the sex organs of their body to the victim Ever threatened to have sex with the victim Ever touched the sex organs of the victim |

Yes 15(5) 7(2.3) 5(1.7) |

No 284(95) 292(97.7) 294(98.3) |

Yes 29(9.7) 35(11.7) 36(12) |

No 270(90.3) 264(88.3) 263(88) |

Yes 105(35.1) |

No 194(64.9) |

| Ever made you touch the sex organs of their body | 4(1.3) | 295(98.7) | 31(10.4) | 268(89.6) | ||

| Ever forced the victim to have sex | 11(3.7) | 288(96.3) | 37(12.4) | 262(87.6) | ||

| had any other unwanted sexual experiences not mentioned above | 3(1) | 296(99) | 2(0.7) | 297(99.3) | ||

| Sexual related history of the respondent | ||||||

| Character | N (%) | N (%) | ||||

| Yes | No | |||||

| Discussing reproductive health with parents | 123(41.1) | 176(58.9) | ||||

| Number of sexual partner in life | ||||||

| One two three four and above I haven’t |

116(38.8) 45(15.1) 34(11.4) 10(3.3) 94(31.4) |

|||||

3.4. Substance use History of the Respondents

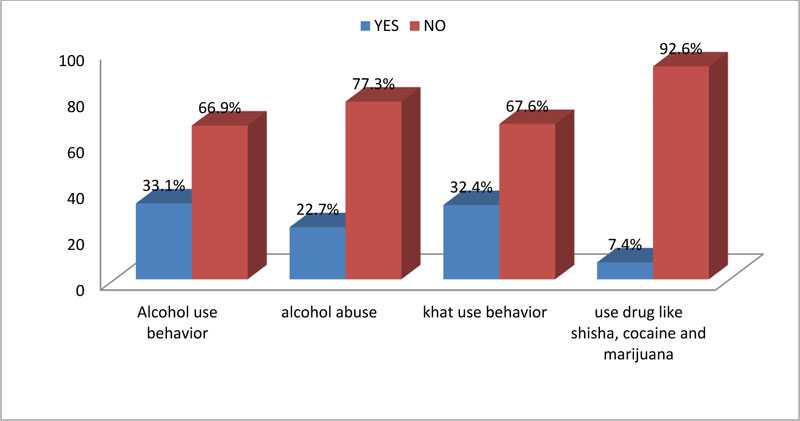

Of the total respondents, 99(33.1%) used alcohol, and of these, 68 (22.7%) scored > 2 on a four-item alcohol abuse identification test, which indicates they abused alcohol. Twenty-two (7.4%) and 97 (32.4%) of the respondents used drugs and chewed Khat in their lifetime, respectively (Fig. 2).

3.5. Factors Associated with Gender-based Violence

Students who were in the third year had a higher risk of lifetime gender-based violence (AOR = 9.06 95% CI: 1.96, 41.95) than second-year students. The same is true in the case of a strict parenting style as the ratio of the likelihood of having gender-based violence was 3.34 times higher (AOR =3.35,95% CI: 1.04, 10.72) than in those with the average family control system (Table 4).

In those who had a history of alcohol consumption and khat chewing, the likelihood of lifetime gender-based violence is around 14 times (AOR =13.8 95%CI: 4.51, 42.45) and 12 times (AOR = 11.5 95% CI: 3.88, 34.47) more likely than those who did not have a history of alcohol consumption and khat chewing, respectively. The likelihood of experiencing lifetime gender-based violence was 90% less likely among those students who had a chance to discuss personal affairs with parents than students who had no chance to discuss personal affairs, especially on sexual issues with parents (AOR= 0.1 95%CI: 0.05,0.54). Lastly, having one or number of sexual partners in life was around three times (AOR 2.9 95%CI: 0.10, 9.79), more likely to experience Gender-based violence than those who had no one or more number of the sexual partner in their life (Table 4).

Variables having association in the final model analysis such as all attributes of substance use (chat chewing, drinking of alcohol, use drug), place of origin in rural areas, tender (age group > or = 25) age, lack of discussing personal affairs with parents, having more than one sexual partner in life, income per year (550-1199, and 1200-1999), living alone, students receiving money on a semester base, the third year students. Regarding family history, those who reported that their mother's educational status was 1-4 grades, annual income of a family in ETB and parenting style over the respondent's behavior were found to be strong covariates of Gender-based violence in their lifetime on crude OR (Table 4 ).

| Character | COR(95% CI) | AOR(95%CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||

| 15-19 | Reference | |||

| 20-24 | 1.5(0.89, 2.65) | 1.7(0.33, 8.77) | ||

| >=25 | 3.3(1.72, 6.55) | 3.9(0.54, 28.59) | ||

| Current living condition | ||||

| living alone | 3.8 (2.009, 7.25) | 1.09(0.24, 5.22) | ||

| with female friend | 0. 5 (0.27, 1.21) | 5.4(0.97, 33.17) | ||

| Others | Reference | Reference | ||

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | Reference | Reference | ||

| Divorced | 1.8(0.99, 3.37) | 1.4(0.20, 10.10) | ||

| Others | 1.08(0.57, 2.04) | 1.2 (0.23, 6.49) | ||

| Study year | ||||

| First | 0.3(0.17, 0.70) | 1.3(0.34, 5.55) | ||

| Second | Reference | Reference | ||

| Third | 3.6(2.02, 6.51) | 9.06(1.96, 41.94)* | ||

| Place of origin | ||||

| Urban | Reference | Reference | ||

| Rural | 2.3(1.28, 4.39) | 0.3(0.06, 1.90) | ||

| Frequency of financial support | ||||

| Monthly | 0.4(0.27, 0.88) | 0.2(0.05, 1.22) | ||

| every semester | Reference | Reference | ||

| Others | 0.7(0.39,1.26) | 1.1 (0.21, 6.25) | ||

| Student’s annual income per year in ETB | ||||

| 0-549 | 0.5(0.25, 1.05) | 0.5(0.04, 7.40) | ||

| 550-1199 | 1.9(1.01, 3.4) | 1.2(0.16, 10.10) | ||

| 1200-1999 | 2.4(1.15, 4.96) | 0.3(0.02, 6.03) | ||

| >=2000 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Family annual income in ETB | ||||

| 0-13199 | 2.1(1.03, 4.25) | 3.2(0.74, 14.15) | ||

| 13200-23999 | 2.4(1.17, 4.96) | 2.2(0.47,10.43) | ||

| 24000-35999 | 2.4(1.27, 4.84) | 0.5(0.11, 2.54) | ||

| >=36000 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Discussing reproductive health issue with parents | ||||

| Yes | Reference | Reference | ||

| No | 20.8(9.18, 47.21) 0.1 (0.05, 0.54)* | |||

| Number of sexual partner in life | ||||

| >=one | 8.3(3.97, 17.43) | 2.9(0.10, 0.98)* | ||

| I haven’t Reference | Reference | |||

| Parents living condition | ||||

| living together | Reference Referee | |||

| divorced/separated | 1.09(0.44, 2.76) | 0.9(0.11,8.006) | ||

| Others | 0.7(0.37, 1.51) | 0.6(0.09, 3.92) | ||

| Continuation of Table 4: Multiple logistic regression: Factors associated independently with sexual violence among college female students in GTTC, North-east Ethiopia, 2018(n=299) | ||||

| Educational status of father | ||||

| Illiterate | 1.02(0.45, 2.32) | 6.8(0.63, 75.31) | ||

| 1-4 grade | Reference | Reference | ||

| 5-8 grade | 0.9(0.47, 1.92) | 0.9(0.12,7.56) | ||

| 9-12 grade | 1.3(0.62, 2.91) | 0.7(0.08, 6.19) | ||

| Above 12 | 1.9(0.88, 4.23) | 0.7 (0.05, 12.60) | ||

| I don’t know | 1.1(0.45, 2.77) | 2.1(0.17, 26.69) | ||

| Educational status of mother | ||||

| Illiterate | Reference | |||

| 1-4 grade | 0.4(0.25, 0.85) | 0.3(0.05, 1.99) | ||

| 5-8 grade | 1.1(0.58, 2.18) | 1.2(0.13, 12.12) | ||

| >= 9 grade | 0.4(0.19, 1.17) | 1.7(0.09, 34.39) | ||

| I didn't know | 0.3(0.12, 0.99) | 0 .7(0.04, 12.47) | ||

| Parenting style | ||||

| Restrict | 6.4(3.00,13.61) | 3.4(1.04,10.72)* | ||

| Average | Reference | Reference | ||

| Loose | 93(26.90,321.06) | 7.1(0.82, 61.90) | ||

| Alcohol use behavior | ||||

| Yes | 54.6(26.33, 113.39) | 13.8(4.5, 42.45)* | ||

| No | Reference | Reference | ||

| Alcohol abuse | ||||

| Yes | 26.3(12.18, 57.06) | 0.7(0.05, 9.97) | ||

| No | Reference | Reference | ||

| khat use behavior | ||||

| No | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 50.8(24.82, 104.05) | 11.5(3.87,34.47)* | ||

| Use drug like shisha, cocaine, and marijuana | ||||

| Yes | 4.4(2.04, 9.51) | 4.3(0.47, 44.70) | ||

| No | Reference | Reference | ||

4. DISCUSSION

In this study, an attempt was made to assess the prevalence and associated factors of gender-based violence. The prevalence of gender-based violence was high, i.e, 35.1% (95% CI: 29.9 - 40.3). Similarly, the study conducted in Mekelle reported a lifetime prevalence of gender-based violence to be 45.4% [11]. The difference in tools used, sample size determined, and characteristics of involved study participants could be some of the reasons. However, this finding is consistent with findings of studies conducted in Namibia, Zambia, and Malawi, which range from 29.4% to 36.4% [12]. Likewise, the current finding is consistent with the random international surveys conducted in Australia, i.e., 35% [13]. However, it is higher than studies conducted in Botswana, Mozambique, South Africa, and Swaziland, ranging from 14.7% to 21.5% [12]. This might be explained by the difference in the study setting, socio-cultural contexts, and sample size between the study populations.

Of the strongly associated factors in this study, a living condition is one of the findings as living alone increased Gender-based violence more than 4 times compared to those living with others (parents, relative, husband), (AOR= 4.3 95%CI: 1.03, 18.09). This is consistent with the findings in the study conducted in Addis Ababa and Mekele [11, 14]. The number of sexual partners in life is another strongly associated factor with Gender-based violence as those who had two or more sexual partners in life had more than 11 times (AOR =11.5 95%CI: 2.80, 47.16) chance of enduring Gender-based violence than those who had one sexual partner in life. This is again consistent with a study conducted at Addis Ababa University among female students [15].

The likelihood of experiencing Gender-based violence among those who had no chance to discuss personal affairs with their parents was five-time (AOR= 5.0 95%CI: 1.37, 18.55) higher than those who had a chance to discuss reproductive health issues with their parents. This is consistent with the study conducted in Bahirdar (AOR = 4.36, 95%CI: 1.40, 13.56) [16]. The reason might be a lack of adequate knowledge of how to deal with sexual issues with perpetrators.

The likelihood of experiencing lifetime Gender-based violence was 3.4 times (AOR= 3.4, 95%CI:(1.04,10.72) more likely among respondents who had a strict parenting style on their behavior than those who had an average parenting style. The reason could be that the average parenting style will provide directions as well as the freedom to decide on personal issues. This fosters their confidence in self-leadership.

Gender-based violence was 90% less likely among those who had monthly financial support (AOR= 0.1, 95%CI: (0.03, 0.73) than those with semester-based financial support. The possible reason could be since they get income timely, as a result, they may not approach male to gain money. Lastly, alcohol use and khat use behaviors were found to be significantly associated with Gender-based violence (AOR = 8.3 95%CI: 2.57, 27.00) and (AOR = 11.05 95% CI: 3.53, 34.60), respectively. Similar findings were documented by studies conducted in Mekelle and Chile [11, 17]. It is difficult from this study to judge which one is causing the other because it is also known that sexual abuse can predispose the victim to increased substance use [18].

The study is internally valid for the following major reasons: The study is done on a population that comes from all zones of the Amhara region, and the result can be generalized to all female college students of the region. A standard tool (sexual abuse history questionnaire) was used to assess Gender-based violence.

However, the study was not without limitations; the magnitude of Gender-based violence might be underestimated because the information was collected only from the survivors during the data collection time. Students could probably be dropped out or remain absent from college because of the violence victimization. In addition, since the study deals with a sensitive issue, underreporting is inevitable. Moreover, it is difficult to show cause and effect relationships as it is a cross-sectional study. Lack of nationally representative figures on the prevalence of Gender-based violence is also another shortcoming. Some other limitations include, the perpetrator/sex offenders related factors were not assessed, the tool (sexual abuse history questionnaire) is not validated in Ethiopia, and males are not included in this study even if they were ever a victim.

CONCLUSION

The prevalence of Gender-based violence among female students in Gonder Teacher Training College was high. Factors found to be significantly associated with Gender-based violence include living alone, lack of the trend of discussing reproductive health issues with their parents, having multiple sexual partners in life and being a third-year student; tight parenting style, and lastly, alcohol and khat use behaviors had positive associations with Gender-based violence. However, earning financial support monthly was a protective factor.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| SGBV | = Sexual and Gender-Based Violence |

| AIDS | = Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome |

| ETB | = Ethiopian Birr |

| HIV | = Human Immune Deficiency Virus |

| IVAWS | = International Violence against Women Survey |

| SPSS | = Statistical Package for Social Sciences |

| SRS | = Simple Random Sampling |

| GTTC | = Gonder Teacher Training College |

| UN | = United Nation |

| WHO | = World Health Organization |

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

MB contributed to the design, conduct, and analyses of the research and in the manuscript preparation. YZ, GB, and MG contributed to the review of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

All procedures followed were by the ethical standards of the responsible committee from the institutional review board of Tseda Health Sciences College , Ethiopia.

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

Not applicable.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Verbal consent was obtained from all study participants for being included in the study.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

FUNDING

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

We all authors announce that we have no competing interests.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

First of all, I would like to thank Tseda health science college for arranging this opportunity to carry out this research thesis. Next, my sincere and deepest thanks go to the college education office for providing me the necessary information and all my friends who have encouraged and helped me during the development of this thesis.