All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Lesson Learned: Developing Life Skills in Youth for Reducing Inequality and Elevating the Quality of Life in Highland Rural School Dormitories of Omkoi District, Chiang Mai, Thailand

Abstract

Background:

Youth dormitory management in Thailand’s education system reveals evidence of discrimination. This is due to the high deviation in educational policy in aspects such as high cost or budget of educational management with dormitory provision in some programmes, when compared to the lower number of youth who receive the benefits of these programmes. Moreover, some programmes are not fair in the selection criteria and had the objectives that responded only to a specific group of population.

Objective:

The objectives of the study were to implement a group intervention programme in life skills development for youth in highland rural school dormitories of Omkoi District, Chiang Mai Province, Thailand.

Methods:

This study used a qualitative research method to recruit and select 30 participants. Semi-structured interviews with open-ended questions were used to collect data from the participants. The thematic analysis method was used for analysing the collected data.

Results:

The findings revealed three themes: 1. The result of analysing and synthesising the context, 2. the result of developing the model, and 3. the result of the life skills development activity programme for youth who lived in the school dormitories.

Conclusion:

Further studies would be required in order to compare the situation between rural and urban areas. Furthermore, youth life skills development programmes should be developed in the appropriate contexts. Moreover, the researcher must pay more attention to the society and culture of the target audience in order to achieve development that would be consistent with the area.

1. INTRODUCTION

Educational situation in Thailand showed the highest number of rural poverty [1-3], which means more variety and more discrimination. Additionally, there are socio-cultural gaps between city and/or urban schools and those in the remote areas [4-7], in particular, the schools in the highland areas [8, 9]. However, a number of school administrators have managed to solve the problems by themselves, which might not correspond with the government policy as they might not be aware of the discrimination [10-17]. Sometimes they even thought that the school providing dormitories did not follow the policy of the central agency [18, 19]. For these reasons, the authors believed that providing suitable dormitories could improve the basic education in each area [1, 20], and this could become a government policy so as to receive support and a broader scope of operation as a means of reducing educational discrimination in the country [19, 21, 22].

As a working group on the Highland Educational System of Chiang Mai to reduce discrimination and enhance the potential of the community with a multidisciplinary approach [10-15], for brainstorming and exchanging data with the administrators and local leaders, the authors collected the data and developed socially responsible research to improve the life skills of the young people in the highland areas to promote their learning [10, 23-25]. The data and concepts exchange about the dormitory operation in each area was commented on by a team of experts and three experienced people, who had been residents or who had operated a dormitory in an educational institution, to obtain an appropriate model for applying in a specific area.

There was also an evaluation on the dormitory operation and success of using a dormitory for life skills development activities for young people through the lesson from the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [26-28]. This was conducted by comparing non-dormitory and dormitory youth under the working group of the project “Sustainable Quality of Life Improvement and Community Potential Promotion in Omkoi District Based on the Royal Initiative of HRH Princess Sirindhorn”, which proved that dormitory youth were distinctively more successful than their non-dormitory counterparts. The research outcome could be used as guidelines for recommendations and improvements of the operation in each area to benefit young people’s life skills improvement and the potential of the community in each area [10, 26, 29]. The conclusion for this research activity on youth dormitories showed that a good management system and dormitory provision could enhance the necessary life skills and experiences for young people and help improve the educational quality [13, 30, 31], as well as the life quality of young people in the highland areas in reducing discrimination in terms of the basic factors for educational management in many aspects [20, 32, 33]. Therefore, it was recommended that the policy section should allocate the budget more responsibly to distribute the resources without discrimination for better and more concrete basic education management.

2. METHODOLOGY

2.1. Research Design

This study used a qualitative research method to recruit and select 30 participants. The objectives of the study were to implement a group intervention programme in life skills development for youth in highland rural school dormitories of Omkoi district, Chiang Mai Province, Thailand. Semi-structured interviews with open-ended questions were used to collect the data from the participants.

2.2. Sample Size and Sampling Technique

Thirty youth in highland rural schools were recruited by a purposive sampling technique.

2.3. Data Collection and Procedure

The research procedure can be summarized, as follows:

Step 1 – Analysed and synthesised the context by means of reviewing the literature, interviewing the related individuals, conducting a field survey, and surveying the underlying problems and shortcomings that would limit the development of quality education in order to gain insights regarding the inequality within the context of youth who lived in school dormitories in the highland areas.

Step 2 – Developed the model by means of studying and analysing the model, and synthesizing and drafting significant dimensions of the development model in order to attain an appropriate guideline that would be practical for the implementation of the pilot model. This covered both the development of life skills and the support system of youth who lived in the school dormitories.

Step 3 – Testing and evaluation of the model by means of selecting two target areas for the experiment with activities developed using the model, as well as by monitoring the results after implementing the model, so to review and summarise the operation’s results, to understand the problems and issues of the development model found from the experimental areas, and present policy-based recommendations for implementing the development model as a pilot model. This was done in order to further expand the programme to other areas of a similar context in the vicinity, where the ultimate result would be the reduction of inequality and the elevation of the quality of education of youth who lived in the school dormitories in the highland areas, which comprised a population in a specialised context whose requirements were somewhat different from youth of general schools.

2.4. Data Analysis

A thematic analysis method was used for analysing the qualitative data. The authors used an audio tape recorder during the interview session and transcribed the data. The programme was of assistance to the authors in highlighting the significant quotes that provided a clearer understanding.

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The results of this study are presented in three main themes: 1. The result of analysing and synthesising the context, 2. the result of developing the model, and 3. the result of the life skills development activity programme for youth who lived in the school dormitories.

3.1. The Result of Analysing and Synthesising the Context

From the survey of the samples of 114 school dormitories in the highland areas of Chiang Mai Province, the authors found that those school dormitories were divided into male and female youth dormitories, respectively. In general, almost every dormitory reported a lack of several necessities, including a dormitory building, youth facilities, etc. Some dormitories faced the problem of overcrowding, lack of good environmental design, and maintenance-related activities [34]. Teachers also served the role of dormitory supervisors, who were assigned maintenance duty to the youth who lived in the school dormitory. Though some school dormitories received support from external organisations and communities, this support was insufficient to address the demands of the youth and parents, especially those youth who lived in areas that were far away from the school. Those youth required appropriate lodging services. Thus, the results of the analysis allowed the authors to categorise the school dormitories in the highland areas into three groups in terms of the difficulty involved with those dormitories. The first group comprised a total of 10 dormitories that experienced moderate difficulty (9%), the second group consisted of 54 dormitories that had high difficulty (47%), and the third group comprised 50 dormitories that had the most difficulty (44%).

3.2. The Result of Developing the Model

For the model of the life skills development activity programme for youth who lived in school dormitories, the authors designed a participatory model that was quite flexible for the implementation, in which the authors integrated the ideas regarding the development of the necessary skills for children and youth in the 21st century in accordance with the adaptation of adolescent teenagers, and created the adolescent adaptation skills development programme for youth who lived in the school dormitories in the highland areas of Chiang Mai Province. The development programme was divided into three steps, as follows:

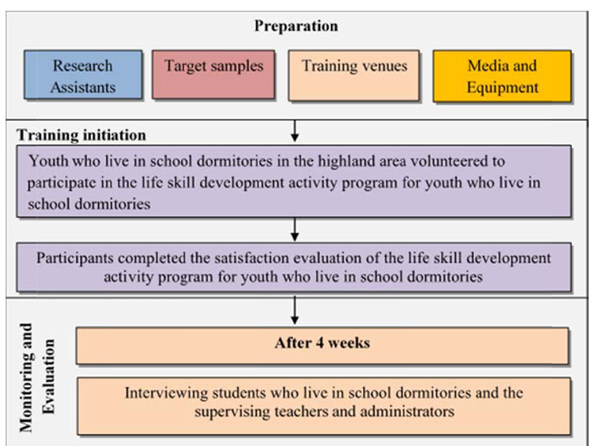

3.2.1. Preparation of the Research

The authors prepared a group of research assistants by explaining to them the details of the training course, the role and duty of the research assistants in the preparation, installation, and distribution of the instruments required for each stage of the activities, as well as their responsibility for gathering the documents or recording the events occurring during the activity in order to create the summary report. After preparing the targeted samples, the authors contacted the administrators of the educational institutions and other related entities in order to request their collaboration and to coordinate with them regarding the guidelines for conducting the training course and for gathering the information about the educational institutions and youth. The authors then worked with them to prepare the training venues for the training programme by collaborating with the related individuals of those educational institutions to provide rooms that were convenient for conducting the training activities. The authors also prepared a sufficient amount of media and equipment required for the training, in accordance with the number of youths that would participate in the training course. The authors placed those media and equipment at the locations that were convenient for the authors and research assistants to access and use, as well as did not block any training activities.

3.2.2. Initiation of the Training Course

The authors brought the targeted youth to the training course, explained to them the importance and the objective of the course, and conducted the course as per the set programme. The training course took half a day to complete with a total period of three hours.

3.2.3. Evaluation and Monitoring of the Results

Four weeks after the training course was completed, the authors evaluated the skills of the youth who participated in the course by conducting an interview with the youth, teachers, and administrators in order to gather information and to analyse the efficiency of the training programme.

3.3. Results of the Life Skills Development Activity Programme for Youth who Lived in School Dormitories

The model of the life skills development for youth who lived in school dormitories that the authors had developed under this research project can be summarized as a protocol (Fig. 1).

The life skills development activity programme for youth who lived in school dormitories contained important content that was necessary for life skills development. The content covered four learning units and four activities. The details and schedule of the programme are shown in Table 1.

| Activities | Duration (Minutes) |

|---|---|

| Unit 1. Orientation | |

| Activity 1. Experiencing the life of youth who lived in school dormitories. | 30 |

| Unit 2. Development of youth’s recognition and understanding of themselves and others |

|

| Activity 2. Know them, know yourself; the value of relationships. | 40 |

| Unit 3. Adolescent life skills development | |

| Activity 3. Immunity for teenagers. | 50 |

| Unit 4. Post training | |

| Activity 4. Lesson for the next steps. | 40 |

For the results of the objective-wise training of each activity of the training programme, the evaluation revealed that the results of those activities achieved the given objectives. The details of the results are as follows:

3.3.1. Activity 1. Experiencing the Life of Youth who Lived in School Dormitories

Aimed to educate the participants - youth who lived in school dormitories - about the objectives of the training course, the role and duty of the researchers and assistants, the schedule of training, and the agreement of training. The authors were responsible for explaining all of these aspects to the participants. From observation, during the explanation, the authors found that the participants were interested in the programme and remained focused for the entire time. Most of the participants reacted to the explanation by nodding, a gesture that reflected their acknowledgement of the subjects they were listening to. Some of the participants raised their hands to ask further questions, which the authors clarified. This activity allowed participants to have a clear picture of the programme and to be ready to participate in the training programme, as well as created familiarity and a good relationship between the participants and authors, and created a training environment that was friendly, safe, and relaxing. The authors started by introducing the team and asking participants to introduce themselves, in which the authors acquired positive collaboration from the participants, as the authors observed that participants paid solid attention to the authors when the research team was introduced. Participants also introduced themselves with great confidence. When the authors conducted an activity where participants must find the names of individuals who possessed the required 10 characteristics, participants actively stood up from their seats to find the list of names of those individuals. During this activity, there was laughing and teasing, as participants interacted with each other in a friendly and confident manner. This was because all of them lived in the same dormitory. Moreover, although there were signs of shyness between the participants of different genders, this did not hinder their ability to adapt to this activity; as a result, they had the opportunity to interact with each other. After checking their answers, the authors found that every participant was able to find the names of the individuals who possessed the required 10 characteristics. This confirmed that the participants were highly cooperative. The authors then randomly selected the answers and called on youth who possessed those characteristics to talk about them in front of everyone. This activity proved to be very amusing for participants, as they loudly clapped their hands and teased their representatives without hindering the overall atmosphere of the activity. Furthermore, their actions revealed their intimacy, feeling of security, safety, and relaxation during the training course. At the end of Activity 1, the authors explained to them the meaning, principle, and benefits of the experience of living with other people in the dormitory and of their adaptation with each other. Everyone seemed to be interested and focused on the subject, as the authors observed from their eye contact and constant nodding. From the aforementioned, it could be summarised that the evaluation of Activity 1 revealed that the objectives were achieved.

3.3.2. Activity 2. Know them, know Yourself; the Value of Relationships

Aimed to 1) allow participants to review and understand their self-images and 2) give participants the opportunity to listen to and learn about the self-images of other people in order to allow participants to adapt themselves in living with other people. For Activity 2, the authors started the session by asking the participants the question of ‘What have you done in your life that makes you feel valuable, or satisfied with yourself, or most proud of yourself?’ The question aimed to stimulate the participants to link and search their experience with the concept. The authors found that every participant easily recalled the experience that they were proud of, which was mainly stories about their lives. In terms of the participants’ reactions when they answered the question, the authors observed that they were all smiling, a gesture that reflected their feeling of happiness with the story they were telling. This activity gave participants the opportunity to draw the image of themselves, to tell their stories and the significance of those stories, and to explain the meaning of the events. For example, when they told their story with a smile on their faces, this could also imply that they were happy and friendly individuals, that they wanted to live with their friends, brothers and sisters, and teachers, and that they also wanted everyone to be happy. The participants’ ability to tell the stories that they were proud of and to assign the value to their lives of studying and to their living was in line with the subject that the authors wanted the youth to find. That is, the authors wanted the youth to recognise their value, to learn the method of recalling the things they were proud of, and to use those things to assure themselves of their value in the future. This method allowed people to live happily with both the past and the present. Simultaneously, defining a target for the future allowed the individuals to be hopeful and determined in their lives and studies. A youth confidently told us that “I intend to graduate and become a nurse. I’m sure that I can do that.” She told this to the authors with a firm voice and a sense of determination in her eyes. As she laid down the plan and target of her life, her action also positively influenced her present life. From the aforementioned, it could be summarised that the evaluation of Activity 2 revealed that the objectives were achieved.

3.3.3. Activity 3. Immunity for Teenagers

Aimed to 1) educate the participants, so they could learn and understand the skills that were necessary for teenagers and 2) allow the participants to apply the knowledge about life skills for teenagers in their daily lives. In Activity 3, the authors showed a video about adaptation during adolescence to the participants and then asked them to discuss the subject in an open debate, followed by answering the questions regarding the subject. The authors also provided further explanations on other subjects; for example, the sexual roles of males and females, physical, mental, and societal changes that occur during adolescence, how to take care of oneself against temptation, as well as how to respect each other. From the observation during the video presentation and further explanation, the authors found that all participants were interested and focused on the subjects they were watching or listening. During the group discussion, the participants formed five-six groups and wrote down their answers, summarised the subjects and ideas that they had gathered from the presentation then presented their summary in front of everyone; the authors observed that the participants worked together quite well during the discussion. They were able to answer the questions quite well, as well as precisely provided their understanding of the importance and the benefits. The authors found that most of the participants perceived that this activity was useful for them in terms of allowing them to learn the necessary skills. Simultaneously, they also perceived that this activity allowed them to learn while collaborating with their peers, those who lived in the same dormitory. They mentioned that ‘I feel more confident to do things and to express my opinion.’, ‘I feel better and more confident to express myself. I understand this subject much clearer.’, and ‘I have learnt many things from both the members of my group and from the presentation of other groups.’ From the aforementioned, it could be summarised that the evaluation of Activity 3 revealed that the objectives were achieved.

3.3.4. Activity 4. Lesson for the Next Steps

Aimed to 1) summarise the underlying subjects of the training programme and 2) allow participants to acknowledge the benefits of the programme and the guidelines for implementing the knowledge acquired from the programme. In Activity 4, the authors explained to the participants the underlying subjects of all these activities. The participants showed signs of their interest and seemed to pay full attention to the presentation. After the authors discussed with the participants; the benefits of the programme and the guidelines for applying the skills they had learnt, it was found that the participants were more actively involved with the activity, whether by answering the questions or expressing their opinions. All the youth reflected and provided their thoughts on the benefits of the programme, as well as the guidelines for applying the skills learnt to their daily lives. They intended to study harder, so they would have a brighter future and intended to avoid any temptation. They discussed and exchanged their opinions, whereas according to their discussion, it could be summarized that the youth who lived in school dormitories that participated in this training programme was able to fully acquire the benefits from the knowledge they had learnt and able to apply the knowledge in their daily life. From the aforementioned, it could be summarised that the evaluation of Activity 4 revealed that the objectives were achieved.

In terms of the evaluation and monitoring, at the fourth week after the training programme, the authors evaluated the skills of the youth who participated in the programme through interviewing those youth, as well as teachers and administrators. It was found that the youth were able to remember and recall the knowledge and experience they had acquired, and to recognise their value from what they had learnt, which they were now applying to their lives, as they lived together in the school dormitories. Additionally, the youth mentioned that they liked the life skills development activities that were conducted. In terms of their level of satisfaction with the provided activities, the youth expressed the highest level of satisfaction. In addition, the youth from these two schools wished that such activities should be held every semester in order to motivate the youth.

CONCLUSION

For the life skills development activity programme for youth who lived in school dormitories [10, 35, 36], it would be necessary to implement the development programme as part of the effort for taking care of youth who lived in school dormitories in order to stimulate them to learn and to adapt appropriately [10]. The implementation could be done by applying the programme developed by the authors as extracurricular activities [32]; for example, youth orientation and participatory activities arranged in the evening or during weekends [32, 37, 38]. Doing so would make youth feel that the dormitory was their second home, thus allowing them the opportunity to develop the necessary basic skills [10, 32-36]. This programme would also simultaneously prepare youth for classroom activities, and it could be applied for separate individual activities [39], as per the characteristics of the youth who lived in the school dormitories.

Private and/or non-profit organisations could provide support and resources to the schools [1, 8, 9]. The allocation of that support and resources would not have to be limited to the context of a classroom, but could also include the context of school dormitories in the highland areas, a specialised context where there are many difficulties and limitations that would need to be overcome [31, 39]. The support of the necessities provided by the private and/or charitable organisations would also assist the burden of the government and the local community. For example, in this research project, the Foundation for Educational Advancement went into the field with the authors and recognised the importance of the schools’ development [1, 5, 8]. Since the Foundation usually builds school buildings for schools that lack resources, they approved the construction of dormitories for schools that were in the targeted area of this research project [1, 31, 39]. Therefore, contributions from private and/or charitable organisations would help reduce educational inequality [4, 7, 19, 21, 22, 26], as well as develop the capacities of the youth’s education.

FUTURE RESEARCH

Additional research would be required to compare the situation between the rural and urban areas. Youth life skills development programmes should also be developed in the appropriate contexts [35, 40]. In particular, researchers would need to pay more attention to the socio-cultural environment of the target audience so to achieve development that would be consistent with the area.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

Priyanut Wutti Chupradit reviewed the literature, designed the research, collected and analyzed the data, and contributed to the publication of the manuscript. Supat Chupradit reviewed the literature, designed the research, collected and analyzed the data, and approved the manuscript. Chanakarn Kumkun collected and analyzed the data. Jedbordin Kumkronglek collected and analyzed the data. Natthanit Joompathong collected and analyzed the data.

ETHICAL STATEMENT

The principal investigator or data collectors briefed the aim of the study to the participants and signed informed consent was taken from all the participants prior to the data collection. During the data collection, confidentiality was ensured and for this reason, the name and the address of the participants were not recorded in the data collection checklist.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Written informed consent was obtained from all workers who voluntarily agreed to participate in the study.

AVAILABILITY OF THE DATA AND MATERIALS

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author [S.C] upon request.

FUNDING

This study was financed in part by the Socially-Engaged Scholarship, Chiang Mai University – Grant Number M000021128.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors gratefully acknowledge funding support from the Socially-Engaged Scholarship, Chiang Mai University, Thailand. The authors also appreciate the cooperation of all participants in this project.