All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

What Explains Country Differences in Covid Death Rates across the Europe? An Exploratory Analysis

1. INTRODUCTION: COVID DEATH RATES ACROSS THE EUROPE

The European Centre for Disease Control (ECDC) provides comparable data on the daily number of newly reported COVID-19 cases and deaths in countries within the European Union and the European Economic Area [1], covering a total of thirty countries. The ECDC’s Covid pandemic material goes back as far as February 2020. For this editorial, an artificial cut-off point of June 27 2022, was chosen and daily counts were summed up for each country for the full past time interval. Ratios were then calculated using population data supplied by the same source [1].

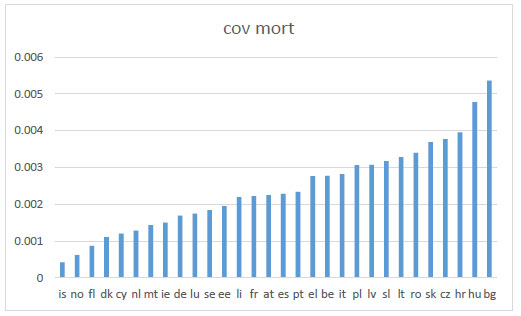

One of the most striking observations gleaned from this long set of Covid information is how much European countries have differed in terms of the Covid mortalities they experienced. Thus Covid mortalities were lowest in Iceland (is) with 0.00042 (or 153 deaths for a population of 364,134), while Bulgaria (bg) was highest with 0.00536 (or 37240 deaths for a population of 6,951,482). Germany (de) fell in the lower middle range with a Covid mortality rate of 0.00169 (or 141020 for a population of 83,166,711. These figures indicate that the experience of the Covid pandemic has been varied across Europe, with some countries being much more severely affected than others. If we were to take the extreme cases of Iceland and Bulgaria, Covid mortality rates would differ by a factor of more than twelve. Similarly, the chance of death from Covid in Bulgaria was thrice more than that in Germany. Suffice it to say that Bulgaria was not an isolated outlier in terms of Covid mortality. Other European countries with high Covid mortality rates included Hungary (hu, 0.004775), Croatia (hr, 003957), Romania (ro, 0.003399), Slovakia (sk, 0.003691), Czechia (cz, 0.00377), and Poland (pl, 0.003067). This was closely followed by Belgium (be, .002769) which had the highest Covid mortality rate among Western EU countries. Seen collectively, these figures are particularly puzzling, given the widespread availability of vaccines across Europe [2] which should have created more of a level playing field. They suggest that national healthcare systems and behaviours impacted significantly on Covid mortality levels (Fig. 1).

The causes and explanations are related to complex institutional, socio-economic, and political differences and dynamics, into which, despite being worthwhile and important, we can provide some tentative exploratory insights.

2. EXPLORATORY ANALYSIS

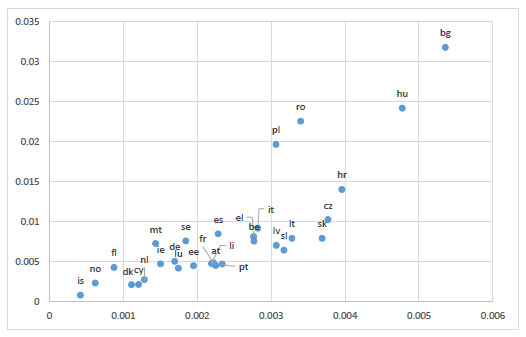

One question which has been widely debated in relation to Covid mortality concerns the significance of the severity of outbreaks, measured or at least approximated by the frequency of recorded Covid cases as compared to the ability of healthcare systems to cope with these pressures. The aforementioned ECDC source [1] lists figures for covid case numbers as well as deaths, and hence allows for proximate analysis of this issue. Put simply, a correlation of a high per capita number of recorded Covid (or case ratio) in a country with a high number of per capita Covid deaths (mortality ratio) would indicate that a national healthcare system experienced difficulties in coping with cases arising from the pandemic.

As shown in Fig. (2), a strong relationship is found between country case ratios and country mortality ratios, which indicates that high European Covid mortality ratios or differentials in relative levels of Covid deaths in Europe may have been driven at least in part by coping differentials within national healthcare systems.

This coping problem seems to be particularly pronounced for Bulgaria and Hungary, where we observe both high Covid case rates and high Covid mortality rates., (Fig. 2). Poland and Romania suffered from high Covid case rates, while mortality rates were in the higher middle end, falling below from those of Croatia, Czechia, Slovakia, Lithuania, and Slovenia.

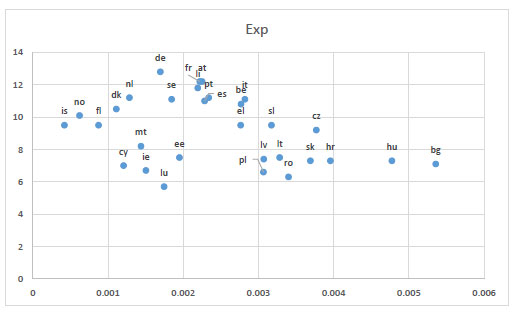

One seemingly simple issue to explore is the relationship between observed Covid mortality differentials and levels of healthcare resourcing. Complications for an exploratory analysis arise from the various choices of resourcing indicators or variables. The variable current expenditure on all levels for health care as a percentage of GDP has historically served as an indicator of health care systems resourcing. Current health expenditure as a share of GDP is assumed to provide a measure of the level of resources channelled to health relative to other uses. The significance of the health sector is evident economically and reflects how health is taken as a societal priority in the country measured in monetary terms. [3]. It also reflects how health spending is growing relative to economic growth [4]. Examining health care financing as a mix of financing arrangements including government spending and compulsory health insurance (“Government/compulsory”) as well as voluntary health insurance and private funds such as households’ out-of-pocket payments, NGOs and private corporations (“Voluntary”) [5], the OECD concluded that as a result of the substantial health spending growth due to Covid and the widespread economic downturn, health spending as a share of GDP jumped to 9.7% across OECD countries in 2020, up from 8.8% in 2019 [6]. Nonetheless, the OECD recorded a number of countries where this percentage fell below the average figure, including Bulgaria, Cyprus, Croatia, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Poland, Romania, and Slovakia.

Fig. (3) plots the relationship between this GDP-based resourcing variable and Covid mortality outcomes.

This exploratory scatterplot indicates the presence of a relationship where higher-spenders (or presumably better-resourced healthcare systems) are, as expected, at the lower end of the European Covid mortality spectrum. However, the relationship is not universal. Thus, some high-spenders countries such as Sweden, achieve only marginally better results than low-spenders like Estonia. However, the very low-spenders, Croatia, Hungary, and Bulgaria appear to be among the most pronounced underperformers among low-spenders, based on the GDP indicator.

Apart from the fact that very high spending does not necessarily produce commensurate returns in terms of healthcare outcomes, or pandemic fatality prevention, some distortions about using healthcare spending as a percentage of GDP arise due to the impact that foreign direct investment has on misrepresenting the true value of the economic activity when measured by GDP. Furthermore, it is not a measure of social or even economic well-being and therefore using it as a measure of health outcomes is unreliable [7].

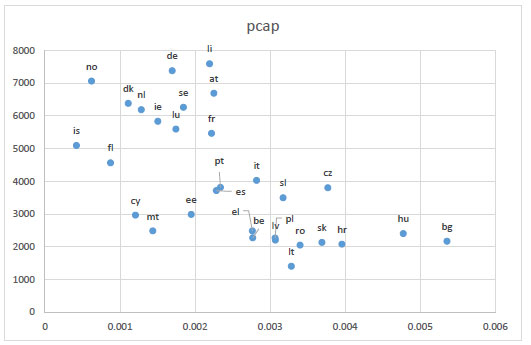

The exploratory analysis therefore also considered the alternative resourcing variable of per capita health care expenditure, which is depicted in Fig. (4). Technically the OECD defines this indicator as the per capita total expenditure on health, expressed at the average exchange rate for that year usually in US$. It shows the expenditure on health relative to the beneficiary population, expressed in US$ to facilitate international comparisons and is said to reflect government and total expenditure on health resources, access and services relative to the population [8].

Fig. (4) which is based on per capita health expenditure data does not differ greatly from Fig. (3) (which utilised health share as a percentage of GDP as a dependent resourcing variable). However, the negative correlation (greater spending relating to lower mortality rates) is more pronounced for Fig. (4), with the main underperformers (Bulgaria, Hungary, and Croatia) again forming the lower right end of the scatterplot, on account of relatively low per capita health spending levels and high Covid pandemic mortality rates.

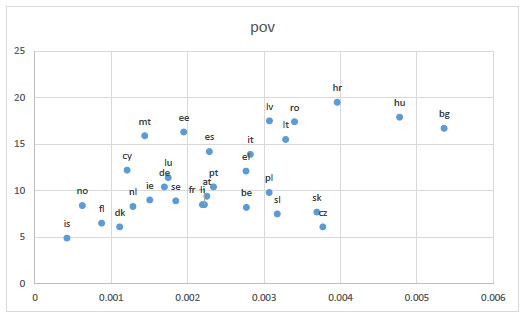

Following this analysis, we explored the relationship of poverty rate data of OECD-reported country with the country’s Covid mortality rates. The OECD defines this rate as the ratio of the number of people (in a given age group) whose income falls below the poverty line; taken as half the median household income of the total population [9, 10]. Such a relationship was considered, not only because European countries with high Covid mortalities were at the poorer spectrum, but also because research from other countries indicated a relationship between poverty and high Covid mortality rates [10]. As shown in Fig. (5), this relationship was not very strong, with only a mildly discernible upward slope.

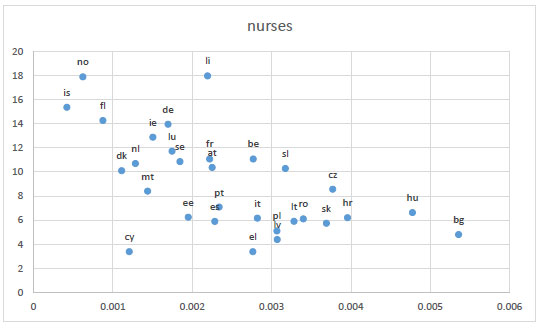

The penultimate variable examined here in relation to European country Covid mortality rates concerns the resourcing variable of nurses, per 1,000 inhabitants, which has again been collected by the OECD. The importance of the relative number of nurses in the Covid pandemic has been highlighted by other authors and we follow this lead [11]. Fig. (6) confirms these views by showing a high negative correlation between a high relative number of nursing staff in a national health system and a low country mortality rate.

| Country | Politician Name | Brief Description of Education | Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| Austria | Sebastian Kurz | Did not complete ug law degree | 0.5 |

| Belgium | Alexander De Croo | Eng degree and MBA | 2.5 |

| Bulgaria | Boyce Borisov | Lecturer police school | 2.5 |

| Croatia | Andrej Plenković | pg(Master) int law | 1.5 |

| Cyprus | Nicos Anastasiades | pg(Master) law | 1.5 |

| Czechia | Andrej Babiš | BA economics | 1 |

| Denmark | Mette Frederiksen | BA and Masters | 2.5 |

| Estonia | Jüri Ratas | D- | 2.5 |

| Finland | Sanna Marin | BA, MA admin | 2.5 |

| France | Emmanuel Macron | Masters Equiv, Doctorate, Acad editor | 3 |

| Germany | Angela Merkel | Dr. rer. nat., Lecturer | 3 |

| Greece | Kyriakos Mitsotakis | Masters, BA Harvard, MBA | 2.5 |

| Hungary | Viktor Orbán | Law degree, JD | 2.5 |

| Iceland | Katrín Jakobsdóttir | BA, MA+, Lecturer | 3 |

| Ireland | Micheál Martin | MA, Dip Ed | 2.5 |

| Italy | Giuseppe Conte | UgLaw, Doc, Professor | 3 |

| Latvia | Krišjānis Kariņš | BA, PhD | 3 |

| Liechtenstein | Prince Alois | Sandhurst, Master | 1.5 |

| Lithuania | Gitanas Nausėda | PHD, Professor | 3.5 |

| Luxembourg | Xavier Bettel | Masters | 1.5 |

| Malta | Robert Abela | Law degree | 1.5 |

| Netherlands | Mark Rutte | MA | 1.5 |

| Norway | Erna Solberg | Cand.mag. | 1.5 |

| Poland | Andrzej Duda | Law degree, LLD lecturer | 3.3 |

| Portugal | António Costa Costa | Law degree | 1.5 |

| Romania | Klaus Iohannis | Ug physics | 1 |

| Slovakia | Zuzana Čaputová | Ug mgmt., course | 1.5 |

| Slovenia | Janez Janša | Ug defence studies | 1 |

| Spain | Pedro Sánchez | Ug, licentate | 1.2 |

| Sweden | Stefan Löfven | Incomplete ug | .0.5 |

Like the broader resourcing variable discussed earlier, this seems to indicate that the resourcing of national health systems within Europe played a crucial role in their ability to cope with the pressure of the Covid Pandemic, whereby relatively well-resourced systems coped better than those which were comparably poor in terms of resources.

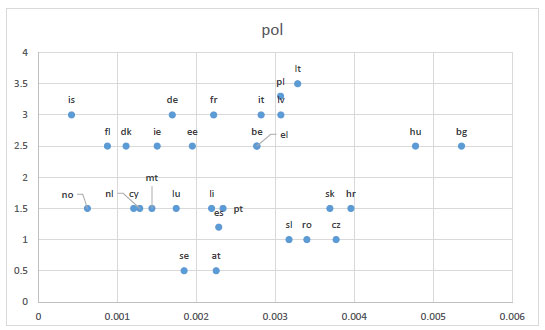

A slightly different tack has been taken by multiple researchers, who have argued that the ability to cope with the Covid Pandemic has depended particularly on political leaders’ willingness to accept scientific advice. In this context, a group of researchers has argued that ‘the countries governed by politicians with a stronger technocratic mentality, approximated by holding a PhD, adopted restrictive containment measures faster in the early, but not in the later, stages of the crisis [12]. While we would not wish to dispute the basic observation of this research, we would doubt that national Covid mortality rates were measurably affected by the education level of national leaders. We examine this in Fig. (7), which is based on a coding of the reported education level of European national leaders (see Table 1). As shown in Fig. (7), there is no discernible relationship between this variable and the Covid mortality rates of European states.

3. CONCLUSION

It can be concluded that the current and the preceding exploratory analysis lend strong support to the idea that the performance of EU and EEA countries in terms of Covid mortality rates during the recent period of more than two years of the pandemic, has been driven primarily by the resourcing aspect. In other words, well-financed healthcare systems, employing ample numbers of skilled healthcare personnel, were more likely to be able to cope with the challenges of covid and prevent high rates of covid mortality.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Matthias Beck is the EIC of the The Open Public Health Journal.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.