All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Primary Health Care: Introducing ‘Village Solidarity Group’ for Effective Operation of Community Clinic in Rural Bangladesh

Dear Editor,

Health, like education, is among the basic capabilities that value human life [1]. It, indeed, contributes to both social and economic prosperity [2]. Health systems are primarily ineffective in reaching the poor, generating less benefit for the poor than the rich and imposing a regressive cost burden on poor households [3]. Neglect, abuse, and marginalization are the issues of their normal experiences [4]. Based on experience, it can be said that poor people will be effectively excluded unless the services are geographically accessible, of decent quality, fairly financed, and responsive [5]. Community Clinic (CC) was introduced as a project in 1998, which was renamed in 2009 as “Revitalization of Community Healthcare Initiatives in Bangladesh” (RCHCIB), targeting about 6000 population at the lowest administrative tier, ward level. Currently (as of September 2017), 13,442 CCs are operational. From July 2015, all the activities of CCs were being carried out under an Operational Plan of the DGHS, Community-based Healthcare (CBHC), which is now being accomplished under the 4th HPNSP (Health Population and Nutrition Sector Programme) 2017-2022. Hundreds of thousands of villagers, particularly the poor and the underprivileged mothers and children, are the beneficiaries of the services from the nearby CCs. The average estimation reveals that about 9.5-10 million patient visits occur nationwide each month in the CCs [6].

It is a matter of irony that despite impressive infrastructural development, particularly in building CCs, the ineffectiveness of healthcare provision is vividly demonstrated in some of those facilities across the country. One of the foremost factors contributing to this situation is the under-utilization of community clinic services (CCS). Reasons for under-utilization of CCS have been attributed to distance of the facility from home, lack of awareness of the value of services, perceived poor quality of care, cultural and social belief systems, discrimination against those of low socio-economic status and perceived high access costs [7]. A significant range of impediments prevails on the side of demand for seeking care from those public facilities, which are evidenced as the use of formal health care is incredibly low (40%); about two-thirds (65%) of which is private health care and only one-fourth utilizes public sector facilities [8]. It was addressed that only 34.1% percent of rural people participate in health services [9].

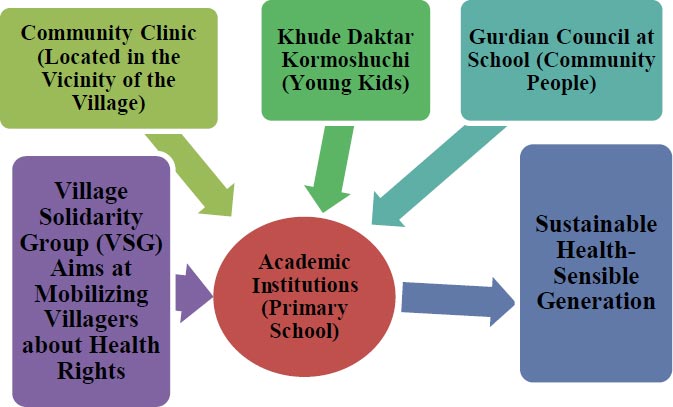

This write-up covers the issue of forming the ‘Village Solidarity Group’ for emboldening ‘Community Support Group’ to effectively tackle the impediments towards the functioning of the Community Clinic (CC). Particularly, there are two graves concerning issues; absenteeism of CHCP (Community Health Care Provider) and the availability of drugs. The idea generated during the period of investigation is that if the inclusive relationship among the academic institution, Community Clinic, Village Solidarity Group (VSG) and the community people; in terms of the village, the relationship among the primary school can be the optimum ground of creating a robust relationship between the health institutions and the community people. Significantly, “Khude Doctor Kormoshuchi” can be strengthened by bringing into the integrated ground. The Guardian Council is called by the school authority to develop a relationship with the guardians for education twice a year. Village Solidarity Group can fill the gap by raising the voice for functioning the CC well. This VSG comprising a group of villagers they selected may talk to the CHCP about the problems he is facing to running. They altogether can try to mitigate that problem. Significantly, this idea of VSG working at the village level as a unit can vigorously help the CSG to ensure the proper dissemination of the CCs.

The authors think that, like the relationship-building works done by the school authority for education, health can be incorporated into the policy table, which will help the villagers understand all the healthcare services available at the Community Clinic. Health providers and other responsible authorities can also listen to what the villagers desire and how to mitigate the misunderstanding about the CC. It is genuinely believed that these sorts of comprehensive approaches can mitigate the misunderstanding about public facilities, i.e., community clinics and figure out the possible ways of brainstorming by the villagers. At that time, they will start to think that CC is created for my and my family’s well-being. They need to contribute whatever they can from their position when the movement towards the pathways of the developed nation turns into reality.

Village Solidarity Group (VSG): ‘Village Solidarity Group’ is a proposed committee comprising 12 to 15 educated and respected members. The committee’s main task is to disseminate information about the available services at those facilities and consult with the members on how to reconcile and act against the barriers in those facilities. This is an idea of a concerted endeavor to resolve the barriers to utilizing health care from the Community Clinic designed for them by the government. A Community Group, composed of 13-17 members, is supposed to make the CC effective by acting on some responsibilities. A Community Support Group (CSG) has been formed to help the CG, each for 3 CG. On that ground, introducing VSG will help bridge the gap between the villagers’ expectations and the inefficiencies in the facility, CC (Fig. 1).

It is high time we realized the importance of emphasizing preventive health care and rigorous health awareness campaign, which can be achieved through bringing these stakeholders; community people (guardians), students (pupils of the primary school), HA (Health assistants who are responsible for Khude Daktar Kormoshuchi), CHCP (Community Health Care Provider who is responsible for running the CC); in the same platform. We are demanding this CC be pro-poor and owned by the community people. Still, community people cannot think as expected because the relationship between the CC and the community people is not smooth enough. What is missing on the ground is a monthly meeting is sufficient with the community so that people can know about the utilization rate, how many drugs are provided by the government, and what steps can help develop the CC. These sorts of discussions would help the community and the CC grow up, mitigating the challenges smoothly.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.