All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Mental Health of Healthcare Workers during COVID-19 Pandemic: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis

Abstract

Introduction

Outbreaks of infectious diseases, such as COVID-19, can lead to psychological distress and symptoms of mental illness, especially among healthcare workers (HCWs) who are at high risk of contracting the infection. This current crisis, in particular, adversely affects mental health due to the rapid spread of the infection from person to person and the uncertainty underlying the treatment guidelines, preventative measures, and the expected duration of its prevalence, which could affect the psychological, emotional, and behavioral symptoms. The purpose of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to identify, evaluate, summarize and analyze the findings of all relevant individual studies conducted to assess mental health symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, it aimed to identify any gaps in the literature, which could identify the potential for future research.

Methods

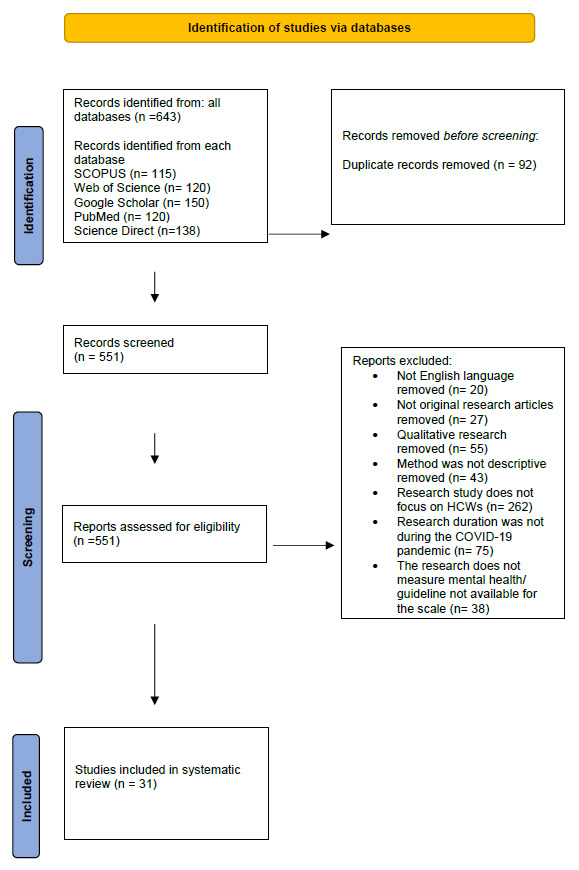

This PRISMA systematic review and meta-analysis on SCOPUS, Web of Science, Google Scholar, PubMed, and Science Direct stated from 11th Feb, 2021 to 11th March, 2022. Following the search to identify relevant literature, one author in the article evaluated the studies in relation to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The systematic review included 31 studies, the meta-analysis of anxiety prevalence analyzed 20 studies and the meta-analysis of severe anxiety prevalence assessed 13 studies.

Results

As per the results that were obtained, for HCW, the most prevalent mental health symptoms were sleep disturbance, depression and anxiety, with a prevalence level of 42.9%, 77.6% and 86.5%, respectively. As per the pooled analysis, anxiety prevalence was recorded as 49% (95%CI, 0.36- 0.62), while for severe anxiety, the number dropped to 8% (95%CI, 0.05–0.10). The highest pooled prevalence of anxiety was observed in Turkey at 60% (95%CI, 0.51- 0.70). Alternatively, the lowest pooled prevalence was observed in China, 36% (95%CI, 0.23–0.50) and India, 36% (95%CI, 0.13–0.62). Based on the review of the relevant articles, a few methodological gaps were identified (i.e., Population of the studies and countries).

Conclusion

This study’s review and meta-analysis provide relevant information pertaining to the mental health status of healthcare workers across the world in light of the COVID-19 pandemic. They experience and endure high levels of mental health symptoms, and thus, it is necessary to provide them with mental and psychological support in this context.

1. INTRODUCTION

The COVID-19 pandemic is a major health crisis that has affected the world population. The virus spread rapidly across the globe, and according to the WHO coronavirus dashboard, the recorded number of cases is over 759 million to date globally, with 6.8 million confirmed deaths. The pandemic has had a profound impact on people’s lives, with a positive correlation between widespread outbreaks and adverse mental health consequences [1, 2]. Healthcare workers (HCWs) are at a particularly high risk of exposure to the virus [3, 4].

Additionally, due to their role of serving patients and educating the public on the protective measures against this virus, they have reported increased workloads and unprecedented life changes [5-7]. The pandemic has also shed light upon the existing inequalities in healthcare systems around the world since vulnerable populations were disproportionately affected by the crisis [8-10]. It is pertinent to work together to address these challenges and support those who were most affected by the pandemic.

Studies conducted during the pandemic outbreak indicated that many participants perceived a deterioration of their mental health [11, 12]. This is not surprising, taking into account the unprecedented nature of the pandemic and the associated stressors, such as social isolation, financial insecurity, and fear of contracting the virus [13-15]. It is natural that the deterioration of the mental health of healthcare workers will be followed by a decrease in the quality of care provided to the patients [16, 17] and increased turnover rates in healthcare settings [18]. Hence, it is crucial to employ systematic review and meta-analysis to study the mental health status of populations during this pandemic, meticulously summarize the available primary research in line with the research question, and synthesize research conducted on a specific, relevant topic.

In general, the objectives of systematic reviews and meta-analyses are to identify, evaluate, summarize and analyze the findings of previous studies on a specific topic. Any existing gaps are then identified to provide direction for future research [19]. A Review published in 2021 summarizes the available evidence to convey how psychological support interventions can help healthcare providers and informal caregivers improve their mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic [20]. Another study analyzed existing evidence on the psychological implications of family caregivers during the COVID-19 pandemic and their mental health outcomes [19].

In previous studies that employed systematic review, the mental health of caregivers was evaluated at an earlier stage of the pandemic [21, 22]. However, the pandemic is advancing and evolving rapidly, and several studies were recently published. These statistics must be accumulated and studied in order to obtain a global picture of the mental health of healthcare professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The objective of this study is to answer the following questions - “what is known in the existing literature about the symptoms of mental health among HCWs during the COVID-19 pandemic?”, “What is the pooled prevalence level of anxiety and severe anxiety among healthcare workers?”, and “what are the existing gaps (i.e., missing elements) in the previous studies?”

2. METHODS

In this study, one author in the paper present a systematic literature review pertaining to the mental health of healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic in adherence to the PRISMA statement for systematic reviews [23]. The method follows a strict process of clarity to improve the study's reliability and reproducibility of the search technique. This study was not prospectively registered with any formal registry.

2.1. Search Strategy, Eligibility Criteria, Study Selection, and Data Extraction

Mental health is a pertinent consideration for all human beings because it covers the gamut of an individual’s behavioral, emotional, and psychological status. During the COVID-19 pandemic, HCWs reported multiple psychological symptoms that significantly altered their lifestyle [24, 25]. This can be attributed to the uncertainty surrounding the period of the pandemic, shortages of personal protective equipment PPE for HCWs, shortage of medical supply, high admission rate, and absence of approved treatments or vaccines [26-28]. Our systematic review focuses on the mental health symptoms experienced by HCWs during the COVID-19 pandemic.

As stated above, the research questions that will be addressed in the study include “what is known in the existing literature about the prevalence of mental health symptoms among HCWs during COVID-19 pandemic?”, “What is the prevalence level of anxiety and severe anxiety among healthcare workers?” and “What are the existing gaps (i.e., missing elements) in the previous studies?”

The literature search was conducted from 11th Feb, 2021 to 11th March, 2022 and involved 643 articles. This period was chosen to collect articles since it was conducive to teamwork and time management, which aided in saving time. It was essential to determine multiple keywords that would function as guidelines to find articles related to the research questions. Expert advice was leveraged to choose the keywords along with a brainstorming strategy and the thesauruses in the databases. Some of the keywords that were selected include “Anxiety”, “Depression”, “Psychological factors”, “Mental health”, “COVID-19”, “Mental disorder”, and “Pandemic”, wherein a few terms were distinct, and others were used in combination.

In order to work in an organized manner, it is crucial to determine the databases. In this study, all the articles were obtained from five different electronic bibliographic valid databases, including SCOPUS, Web of Science, Google Scholar, PubMed, and Science Direct, since they are considered to be primary sources of articles related to health.

A total of 643 articles were collected, with the number varying for each database: 115 articles from SCOPUS articles, 120 articles from Web of Science, 150 articles from Google Scholar, 120 articles from PubMed, and 138 articles from Science Direct (Fig. 1).

In this study,the studies that were eligible for inclusion met the following criteria: 1) Research study is measuring mental health; 2) the Study’s focus is on HCWs; 3) the Study’s time period was during the COVID-19 pandemic; 4) English language; 5) Quantitative research (descriptive, comparative and/or correlation studies); 6) Measurement scale used adheres to known guidelines and cut-offs. Studies were excluded if they met the following criteria: 1) Incomplete text or data not available; 2) Qualitative research; 3) duplicate articles; 4) Language used in the study was not English (Fig. 1).

Before screening the articles (n= 643), Mendeley App was employed to identify duplicate articles (n = 92). Four members were assigned to perform the screening of the articles by reviewing the title and the abstract for each article independently. They were then instructed to discuss the excluded articles and the outcomes of the included articles. This data were collated in one sheet.

To conduct the meta-analysis, a single proportion test using R software was performed to measure the pooled prevalence of anxiety and severe anxiety in HCWs during the COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, subgroup analysis (i.e., location-wise) was utilized to assess the pooled prevalence of anxiety in different geographical areas. Although prevalence meta-analyses frequently produce significant I2 values, this estimation is subject to bias and is not a measure of heterogeneity. High I2 values do not imply significant inter-study variability and may not be discriminative. For assessing heterogeneity in prevalence meta-analyses, prediction intervals are determined to be the optimal option. Sensitivity analyses were also performed in the study to address this heterogeneity, which was resolved in the subgroup Saudi Arabia [29].

2.2. Quality Assessment of the Reviewed Studies

In every review that analyzes different studies, a step is introduced to check how good the research is. This is to determine whether the study was conducted well and the extent of bias that was avoided in its plan, process and results. In order to check the quality of the articles, several tools can be employed [29]. The articles used in this study had one common factor, which is that they determined the prevalence of psychological symptoms. Thus, the JBI checklist was used to determine how good the articles were for this kind of data. Once the articles were checked, a meta-analysis was performed on 20 articles to find out the average rate of anxiety and on 13 other articles to find out the average rate of severe anxiety among HCWs (Tables 1 & 2).

| First Author Name/Ref. | Year | Country | Participants | Prevalence of Anxiety |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hong S [30] | 2021 | China | 4,692 | 379 |

| Zhu Z [31] | 2020 | China | 5062 | 1218 |

| Que J [32] | 2020 | china | 2285 | 1052 |

| Lai J [2] | 2020 | China | 1257 | 560 |

| Mattila E [33] | 2021 | Finland | 1995 | 1361 |

| Xiong H [34] | 2020 | China | 223 | 91 |

| Al Ammari M [5] | 2021 | Saudi Arabia | 720 | 357 |

| AlAteeq DA [35] | 2020 | Saudi Arabia | 502 | 258 |

| Skoda EM [36] | 2020 | Germany | 2224 | 1923 |

| Apisarnthanarak A [37] | 2020 | Thailand | 160 | 68 |

| Badahdah A [38] | 2021 | Oman | 509 | 329 |

| Cai Z [39] | 2020 | China | 709 | 333 |

| Juan Y [40] | 2020 | China | 456 | 144 |

| Mahendran K [41] | 2020 | China | 120 | 64 |

| Pouralizadeh M [42] | 2020 | Iran | 441 | 324 |

| Şahin MK [43] | 2020 | Turkey | 939 | 565 |

| Uyaroğlu OA [44] | 2020 | Turkey | 113 | 56 |

| Jambunathan P [45] | 2020 | India | 257 | 59 |

| Korkmaz S [46] | 2020 | Turkey | 140 | 99 |

| Gupta B [47] | 2020 | India | 368 | 181 |

| Total | - | - | 23,172 | 9421 |

| First Author Name/Ref. | Year | Country | Participants | Prevalence of Severe Anxiety |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lai J [2] | 2020 | China | 1257 | 66 |

| Mattila E [33] | 2021 | Finland | 1995 | 88 |

| Xiong H [34] | 2020 | China | 223 | 8 |

| Al Ammari M [5] | 2021 | Saudi Arabia | 720 | 60 |

| AlAteeq DA [35] | 2020 | Saudi Arabia | 502 | 77 |

| Apisarnthanarak A [37] | 2020 | Thailand | 160 | 8 |

| Badahdah A [38] | 2021 | Oman | 509 | 42 |

| Mahendran K [41] | 2020 | China | 120 | 20 |

| Pouralizadeh M [42] | 2020 | Iran | 441 | 84 |

| Şahin MK [43] | 2020 | Turkey | 939 | 72 |

| Uyaroğlu OA [44] | 2020 | Turkey | 113 | 9 |

| Jambunathan P [45] | 2020 | India | 257 | 2 |

| Gupta B [47] | 2020 | India | 368 | 27 |

| Total | - | - | 7604 | 563 |

3. RESULTS

3.1. Search results and Characteristics of the Studies

Initially, 643 articles were identified from different databases. Once the duplicates were eliminated and each paper was checked, 31 articles were chosen for our review (see Fig. 1 for the PRISMA flowchart). Overall, the 31 studies studied 31545 people, which is evident in Table 3. The majority of studies were conducted in China (15), India (4), Saudi Arabia (3), and Turkey (2). The rest of the studies were conducted in 7 different countries.

| S.NO | First Author Name/Ref. | Year | Country | Population | Dep. | Type of Study | Respondent | Scale | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Zhuo K [56] | 2020 | China | Physicians Nurses |

Children’s Hospital | Cross-sectional study | 26 | ISI. SRQ-20. |

ISI: Mean,7.69 (SD, 5.11), which indicates Subthreshold insomnia SRQ-20: Mean,4.19 (SD,3.47), low score as the Optimal SRQ-20 cut-off score is > = 6 points |

| 2 | Kang L [50] | 2019 | China | Physician Nurses | Hospitals in Wuhan | Cross-sectional study | 994 | PHQ-9. | PHQ-9: 36.9% had subthreshold mental health disturbances (mean PHQ-9: 2.4)/ 34.4% had mild disturbances (mean PHQ-9: 5.4)/ 22.4% had moderate disturbances (mean PHQ-9: 9.0)/ and 6.2% had severe disturbance (mean PHQ-9: 15.1) |

| 3 | Que J [32] | 2020 | China | Physicians Medical residents Nurses/ Technicians/ Public health professionals |

different regions throughout China (online) | Cross-sectional study | 2285 | GAD-7 PHQ-9 ISI |

GAD-7: No Anxiety (n= 1233, 53.96%)/ Mild Anxiety (n= 787, 34.44%)/ Moderate/severe (n= 265, 11.60%) PHQ-9: None (n= 1271, 55.62%)/ Mild (n= 721, 31.55%)/ Moderate-severe (n= 293, 12.82%) ISI: None (n= 1628, 71.25%)/ Subthreshold (n= 502, 21.97%)/ Moderate/severe (n= 155, 6.78%) |

| 4 | Cai Z [39] | 2020 | China | Nurses | pandemic center in Wuhan | Cross-sectional study | 709 | PHQ-9 GAD-7 ISI |

PHQ-9: Normal (n= 335, 47.2%)/ Mild (n= 265, 37.4%)/ Moderate-severe (n= 109 15.4) GAD-7: Normal (n= 376, 53.0%)/ Mild (n= 249, 35.1%)/ Moderate-severe (n= 84 11.8%) ISI: Normal (n= 436, 61.5%)/ Mild (n= 207, 29.2%)/ Moderate-severe (n= 66, 9.3%) |

| 5 | Lai J [2] | 2020 | China | Physicians or nurses. | hospitals in Wuhan | Cross-sectional study | 1257 | PHQ-9. GAD-7. ISI. IES-R. |

PHQ-9: Normal depression (n= 623, 49.6%)/ Mild depression (n= 448, 35.6%)/ Moderate depression (n=108, 8.6%)/ Severe depression (n= 78, 6.2%) GAD-7: Normal anxiety (n= 697, 55.4%)/ Mild anxiety (n= 406, 32.3%)/ Moderate anxiety (n=88, 7.0%)/ Severe anxiety (n= 66, 5.3%) ISI: Absence of insomnia symptoms (n= 830, 66.0%)/ Subthreshold of insomnia symptoms (n= 330, 26.2%)/ Moderate insomnia symptoms (n= 85, 6.8%)/ Severe of insomnia symptoms n= 12, 1.0%) IES-R: Normal distress symptoms (n= 358, 28.5%)/ Mild distress symptoms (n= 459, 36.5%)/ Moderate distress symptoms (n= 308, 24.5%)/ Severe distress symptoms (n= 132, 10.5%) |

| 6 | Hou T [57] | 2020 | China | HCWs | local hospitals, community health service centers and government departments in Jiangsu Province | Cross-sectional study | 1472 | SCL-90. |

SCL-90: (mean, 110.28 & SD, 28.89) no psychiatric symptoms SCL-90 < 160 points |

| 7 | Wang N [58] | 2021 | China | HCWs | N/A (1,967 healthcare workers) | Cross-sectional study | 431 | GHQ-12. | GHQ-12: Poor mental health (n= 81, 18.8%, GHQ-12 > 3)/ High mental health (350=n, 81.2%, GHQ-12 ≤ 3) |

| 8 | Liao C [59] | 2021 | China | Nurses | Zigong First People’s Hospital | Cross-sectional study | 1092 | SASRQ. | SASRQ: Stress (Mean: 33.15, SD: 25.551) |

| 9 | An Y [52] | 2020 | China | Nurses | Emergency Department | Cross-sectional study | 1103 | PHQ-9 | PHQ-9: Mild depression (n= 305, 27.7%)/ Moderate depression (n= 95, 8.6%)/ Moderate-to-severe depression (n= 58, 5.3%)/ Severe depression (n= 23, 2.1%) |

| 10 | Hong S [30] | 2021 | China | nurses | 42 hospitals in Chongqing. | Cross-sectional study | 4,692 | PHQ-9 GAD-7 |

PHQ-9: Depression prevalence (n = 442, 9.4%)/ GAD-7: Anxiety prevalence (n = 379, 8.1%) |

| 11 | Juan Y [40] | 2020 | China | Physicians Nurses |

five national COVID-19-designated hospitals in Chongqing |

Cross-sectional study | 456 | PHQ-9 GAD-7 IES-R |

IES-R: Sub-clinic (n= 259, 56.8%)/ Mild (n= 148, 32.5%)/ Moderate-severe (n= 49, 10.7%) GAD-7: None (n= 312, 68.4%)/ Mild (n= 123, 27.0%)/ Moderate-severe (n= 21, 4.6%) PHQ-9: None (n= 321, 70.4%)/ Mild (n= 106, 23.2%) /Moderate-severe (n= 29, 6.4%) |

| 12 | Xiong H [34] | 2020 | China | nurses | one of the public tertiary hospitals in Xiamen, Fujian Province | Cross-sectional study | 223 | GAD-7 PHQ-9 |

GAD-7: Mild Anxiety (n= 64, 28.7%)/ Moderate Anxiety(n= 19, 8.5%)/ Severe Anxiety (n= 8, 3.6%) PHQ-9: Mild Depression (n= 44, 19.7%)/ Moderate Depression (n= 11, 4.9%)/ Severe Depression (n= 3, 1.3%)/ Extremely severe Depression (n= 1, 0.5%) |

| 13 | Mahendran K [41] | 2020 | China | Dental Staff | Guy’s Hospital. | Cross-sectional study | 120 | GAD-7 |

GAD-7: Missing (N= 10, 8.3%)/ None (n= 46, 38.3%)/ Mild (n= 25, 20.8%)/ Moderate (n= 19, 15.8%)/ Severe (n= 20, 16.7%) |

| 14 | Zhu Z [31] | 2020 | China | Physicians / Nurses/ Clinical technicians |

Tongji Hospital | Cross-sectional study | 5062 | PHQ-9 GAD-7 IES-R |

PHQ-9: Depressive HWs (n = 681, 13.5%) / non-depressive ones (n = 4381, 86.5%) GAD-7: Anxious HWs (n = 1218, 24.1%) / non-anxious ones (n = 3844, 75.9%) IES-R: Psychological stress (n = 1509, 29.8%)/ non-psychological stress (n = 3553, 70.2%) |

| 15 | Gupta B [47] | 2020 | India | Physicians Nurses dentists paramedic staff |

Primary, Secondary, Tertiary and Not a health care facility | Cross-sectional study | 368 | GAD-7. SQS |

GAD-7: Severe anxiety (n= 27, 7.3%)/ Moderate anxiety (n= 46, 12.5%)/ Mild anxiety (n= 108, 29.3%)/ Minimal anxiety (n= 187, 50.8%) SQS: poor-to-fair sleep quality (116, 31.5%) |

| 16 | Suryavanshi N [51] | 2020 | India | HCWs. | N/A (online survey among HCPs) | Cross-sectional study | 197 | QoL PHQ-9. GAD-7 . |

QoL: Low Quality of life (n= 89, 45%, QoL <4)/ Average Quality of life (n= 53, 27%, QoL = 4)/ High Quality of life (n= 55, 28%, QoL >4) PHQ-9: Moderate to severe depression (n= 44, 22%, PHQ-9 ≥10) GAD-7: Moderate to severe anxiety (n= 56,29%,GAD-7 ≥8) |

| 17 | Zheng R [60] | 2021 | India | Pediatric Nurses | nurses working in Hubei province | Cross-sectional study | 617 | DASS-21 | DASS-21: Extremely severe Depression (n=7, 1.1%)/ Extremely severe anxiety (n= 30, 4.9%)/ Extremely severe stress (n= 6, 1%) |

| 18 | Jambunathan P [45] | 2020 | India | Doctors and nurses. | various tertiary care and secondary care hospitals across India | Cross-sectional study | 257 | GAD-7. | GAD-7: Mild anxiety level (n=40, 15.60%)/ Moderate anxiety level (n= 17, 6.70%)/ Severe anxiety level (n=2, 0.70%) |

| 19 | Korkmaz S [46] | 2020 | Turkey | Physicians/ Nurses/ Assistant healthcare staff |

Hospital OPD & or ED | Cross-sectional study | 140 | WHOQOL-BREF. BAI. |

BAI: Participants without anxiety (n= 41, 29%)/ Mild anxiety (n= 53, 38%)/ Significant anxiety (n= 46, 33%). WHOQOL-BREF: scores were found to be lower |

| 20 | Şahin MK [43] | 2020 | Turkey | Physicians Nurses |

N/A online questionnaire | Cross-sectional study | 939 | GAD-7 PHQ-9 ISI IES-R |

PHQ-9: Normal (n= 210, 22.4%)/ Mild (n= 376, 40.0%)/ Moderate (n= 205, 21.8%)/ Moderately severe (n= 90, 9.6%)/ Severe (n= 58, 6.2) GAD-7: Normal (n= 374, 39.8%)/ Mild (n= 387, 41.2)/ Moderate (n= 106, 11.3%)/ Severe (n= 72, 7.7%) ISI: Normal (n= 466, 49.6%)/ Sub-threshold (n= 335, 35.7%)/ Moderate (n= 117, 12.5%)/ Severe (n= 21, 2.2%) IES-R: Normal (n= 222, 23.6%)/ Mild (n= 416, 44.3%)/ Moderate (n= 171, 18.2%)/ Severe (n= 130, 13.8%) |

| 21 | Uyaroğlu OA [44] | 2020 | Turkey | Physicians | Online/ tertiary care university hospital | Cross-sectional study | 113 | GAD-7: | GAD-7: Minimal level / None (n= 57, 50.4%)/ Mild anxiety (n= 35, 31%)/ Moderate anxiety (n= 12, 10.6%)/ Severe anxiety (n= 9, 8%) |

| 22 | Al Ammari M [5] | 2021 | Saudi Arabia | Physicians, Nurses, Respiratory therapists, Pharmacists and Lab Technicians | tertiary care and Ministry of Health centers across the Central, Eastern, and Western regions of Saudi Arabia | Cross-sectional study | 720 | PHQ-9. GAD-7. ISI. |

GAD-7: Mild Anxiety (n= 205, 28.47%)/ Moderate Anxiety (n= 92, 12.77%)/ Severe Anxiety (n= 60, 8.33%) PHQ-9: no depression (n= 366, 50.83%)/ Mild depression (n= 188, 26.1%)/ Moderate depression (n= 94, 13%)/ Moderate Severe depression (n= 57, 7.91%)/ Severe Depression (n= 15, 2.08%) ISI: no insomnia (n= 411, 57.08%)/ Sub threshold insomnia (n= 207, 28.75%)/ Moderate Severe insomnia (n= 75, 10.41%)/ Severe insomnia (n= 27, 3.75%) |

| 23 | Zaki NF [61] | 2020 | Saudi Arabia | Nurses/ Allied health professionals/ Physicians/ pharmacists |

All hospital staff (those working in the medical, paramedical, administrative, and assistant services) | Cross-sectional study | 1460 | IES-R. | IES-R Total score (Mean 35.2, SD 17.1Min 1, Max 89) |

| 24 | AlAteeq DA [35] | 2020 | Saudi Arabia | Administrators/ Nurses/ Physicians/ non-physician specialists/ technicians/ pharmacists |

Ministry of Health | Cross-sectional study | 502 | PHQ-9. GAD-7. |

GAD-7: Mild Anxiety (n= 126, 25.1%)/ Moderate Anxiety (n= 55, 11%)/ Severe Anxiety (n= 77, 15.3%). PHQ-9: Mild depression (n= 105, 24.9%)/ Moderate depression (n= 73, 14.5%)/ Moderately severe depression (n= 50, 10%)/ Severe depression (n= 29, 5.8%). |

| 25 | Kim SC [53] | 2020 | USA | Nurses | Acute care hospital, Primary care clinic, Academic setting and Skilled nursing facility | Cross-sectional study | 320 | PSS. GAD-7. PHQ-9. |

PSS: Moderate/high Stress (n= 256, 80%, PSS ≥ 14) GAD-7: Moderate/Severe Anxiety (n= 138, 43%, GAD-7 ≥ 10) PHQ-9: Moderate/Severe Depression (n= 83, 26%, PHQ-9 ≥ 10) |

| 26 | Tahara M [62] | 2021 | Japan | Physicians, Nurses, Physical therapists, Occupational therapists, Speech therapist | N/A (healthcare workers in Japan) | Cross-sectional study | 661 | GHQ-12. | GHQ-12: Poor mental health (n= 440, 66.6%, GHQ-12 ≥ 4) |

| 27 | Mattila E [33] | 2021 | Finland | HCWs | all hospital staff working at two Finnish specialized medical care centers | Cross-sectional study | 1995 | GAD-7. | GAD-7: Mild anxiety (n = 1,079, 30%)/ Moderate anxiety (n= 194, 10%)/ Severe anxiety 5% (n = 88) |

| 28 | Apisarnthanarak A [37] | 2020 | Thailand | Physicians/ Nurses |

2 university hospitals | Cross-sectional study | 160 | GAD-7 |

GAD-7: Minimal anxiety (n= 51, 31.8%)/ Mild anxiety (n= 37, 23.1%)/ Moderate anxiety (n= 23, 14.4%)/ Severe anxiety (n= 8, 5%) |

| 29 | Badahdah A [38] | 2021 | Oman | Physicians/ nurses |

Several health facilities in Oman. | Cross-sectional study | 509 | GAD-7. PSS-10. |

GAD-7: Minimal anxiety (n= 181, 35.5%)/ Mild anxiety (n= 197, 38.7%)/ Moderate anxiety (n= 90, 17.7%)/ Severe anxiety (n= 42, 8.3%) PSS-10: low stress (n= 222, 43.6%, PSS-10<24)/ high stress (n= 287, 56.4%, PSS-10⩾24) |

| 30 | Pouralizadeh M [42] | 2020 | Iran | Nurses | 25 hospitals of Guilan University of Medical Sciences | Cross-sectional study | 441 | GAD-7. PHQ-9. |

GAD-7: Mild (n= 153, 34.7%)/ Moderate (n= 87, 19.7%)/ Severe (n= 84, 19.0%) PHQ-9: None-minimal (n= 128, 29.0%)/ Mild (n= 148, 33.6%)/ Moderate (n= 88, 20.0%)/ Moderately severe (n= 47, 10.7%)/ Severe (n= 30, 6.8%) |

| 31 | Skoda EM [36] | 2020 | Germany | Physicians/ Nursing staff/ Paramedics |

N/A online | Cross-sectional study | 2224 | GAD-7 | GAD-7: Generalized anxiety below cutoff (n= 10 940, 85%, GAD-7 < 10)/ Generalized anxiety above cutoff (n= 1923, 15%, GAD-7 ≥ 10) |

The 31 articles studied in this research were arranged in the following cross table, with the aim of summarizing the following information: First Author Name, Year, Country, Population, Department, Type of study, Measurement Scale, and results (Table 3).

Prior studies employed the Self-Report Questionnaire (SQS) to rate participants' sleep quality. This tool helps in gauging the quality of sleep of an individual across a seven-day recall period by directing the research participants to rate each of the following five categories with an integer score ranging from 0 to 10, wherein 0 is awful, and 10 is wonderful. Participants were instructed to consider the following fundamental aspects of sleep quality when using the SQS: the number of hours they slept, the ease with which they fell asleep, how frequently they woke up during the night (other than to use the bathroom), how frequently they woke up earlier than necessary in the morning, and how rejuvenating their sleep was.

The Insomnia Severity Index (ISI), a measure of sleep disruption, was also employed in various studies. The type, intensity, and effects of insomnia are evaluated using a 7-item self-report questionnaire. The questions measure the severity of sleep problems, such as trouble falling asleep, staying asleep, or waking up too early, how unhappy the person is with their sleep, the extent to which the sleep problems affect their daily life, how noticeable the sleep problems are to others, and how upset the person is about their sleep problems. The questions inquire specifically about the previous month. Each question has 5 possible answers (0 = no problem; 4 = very bad problem), and the total score ranges from 0 to 28 and determines the severity of insomnia: no insomnia (0–7), mild insomnia (8–14), moderate insomnia (15–21), and severe insomnia (22–28).

Six studies specifically assessed sleep disturbances, which reported a disturbance in 33.9%, 42.9%, 31.5%, 40.9%, 38.5%, and 28.8% of participants, respectively (2,5,32,39,45,47). The study concluded that 38.5% of study participants experience moderate to severe sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome [48], and another study found moderately severe to severe insomnia in 14.16% of the enrolled HCWs (5). Moreover, a significant decrease in sleep quality was associated with higher anxiety [47].

Previous studies utilized the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 scale (PHQ-9) to assess depression, which comprises nine questions that evaluate depressive symptoms that are consistent with the major depressive disorder diagnostic criteria. Higher scores indicate more severe depression. Each question is rated on a four-point Likert scale (0–3), with values ranging from 0 to 27. Scores exceeding 10 are indicators of the individual being in the depressed range [49]. Many studies measured depression among HCWs, and depression symptoms were reported by 63%, 22%, 50.4%, 49.1%, 51%, 43.6%, 52.8%, 9.4%, 29.6%, 70.9%, 44.4%, 77.6%, 26.4%, and 13.5% of their participants respectively [2, 5, 30-32, 34, 35, 39, 40, 42, 43, 50-52]. Furthermore, participants who experience social isolation reported depressive symptoms that are threefold higher [53].

The majority of the previous studies assessed anxiety levels using General Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7). It includes seven items for measuring signs of concern and anxiety. The total scores for each item range from 0 to 21, with higher numbers indicating more severe anxiety. Each item is assessed on a four-point Likert scale (0–3). Scores exceeding 10 are indicators that the patient is in the clinical range [54]. A total of 19 articles assessed the prevalence of anxiety among HCWs, with the three highest prevalence levels being 86.5%, 73.4% and 70.7% of their participants, respectively [36, 42, 46]. In one study, the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) was used to gauge how frequently a person experiences anxiety symptoms. It is a self-report evaluation tool with 21 items and a three-point Likert scale (0–3). Anxiety is measured with scores ranging from 0 to 7, mild anxiety between 8 and 15, moderate anxiety between 16 and 25, and severe anxiety between 26 and 63. The greater the score, the more anxiety the person is experiencing [55]. The results demonstrated anxiety was prevalent in 71% of the population [46].

Two research gaps were identified by the results of the study. Previous studies focused on assessing the healthcare specialists working in the hospitals (i.e., nurses and physicians) while neglecting to study the prevalence of symptoms among respiratory therapists who are at the highest risk of contracting COVID-19 infection. Even though the pandemic’s effects have spread globally, there is a notable limitation of literature conducted in some countries, particularly in the Arab countries (i.e., Jordan, Egypt, Yemen etc.).

3.2. Meta-analysis of Anxiety

A meta-analysis was performed on articles studying anxiety in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. The following pooled prevalences were estimated: 49% of anxiety (95%CI, 0.36- 0.62), out of 23,172 participants (Fig. 2); 8% of severe anxiety (95%CI, 0.05–0.10) out of 7604 participants (Fig. 3). Subgroup analyses were conducted for different geographical locations, and the result demonstrated that the highest prevalence of anxiety was 60% (95%CI, 0.51- 0.70) in Turkey and 50% (95%CI, 0.48–0.53) in Saudi Arabia. On the other hand, the lowest prevalence was 36% (95%CI, 0.23–0.50) in China and 36% (95%CI, 0.13–0.62) in India. (Fig. 4) The highest prevalence level of mental health symptoms among HCWs was 42.9%, 77.6% and 86.5% of sleep disturbance, depression and anxiety, respectively.

4. DISCUSSION

In this section, our findings will be summarized and conveyed to provide a clear overview of the results and draw attention to areas of prominent gaps in the literature.

4.1. Main Findings

HCWs render care and services to ill patients. Since they undertook an essential role in fighting the COVID-19 pandemic, all specialists who worked in hospitals played a valuable role in managing and guiding the treatment plan of patients diagnosed with COVID-19. However, some of them worked on the frontlines.

The articles in this systematic review encompassed a wide range of disciplines regardless of the nature of their workplaces, such as nurses, physicians, paramedics, pharmacists, nutritionists, occupational therapists, physiotherapists, speech and language pathologists, and clinicians. A few articles that were chosen performed studies on HCWs who worked at the hospital in general. Even though the role played by the respiratory care departments in hospitals through the COVID-19 pandemic was significant and honorable, a limited number of articles assessed the mental health of respiratory therapists who worked in the critical ICU during the pandemic (5). Thus, future researchers should focus on this area.

This systematic review covered studies conducted in different continents to assess the mental health of HCWs during the pandemic: Asia (India, China, Turkey, Japan, and Saudi Arabia), the USA, and Europe (Spain and Finland). There are some limitations concerning the countries covered, especially due to the absence of articles from the Arab countries (i.e., Jordan, Iraq, Lebanon, Syria). Thus, the result cannot be generalized for the worldwide population. This vast gap may help the researchers find a zone to focus on.

Additionally, meta-analysis is a study of many similar research types that helps provide a conclusion regarding the overall situation of the variable of interest (63,64). This study demonstrated extremely high pooled prevalences of anxiety among caregivers during the COVID-19 pandemic (49% (95%CI, 0.36- 0.62)). Other studies assessing how HCWs felt during the COVID-19 pandemic reported that they experienced high levels of anxiety (23.2% (95% CI, 17.8–29.1) (21); 26% (95% CI, 18%–34%) (65). Our results were similar to those of other studies, which is a testament to its reliability. Since there has been an abundance of publications on this topic in recent times, This review provides the most current and comprehensive information. The prevalence estimates may vary because of different factors, such as the endurance of the pandemic and its effects on the well-being of HCWs and their specific stressful experiences. Also, this study is different from previous studies due to its focus on determining the pooled prevalence of severe levels of anxiety (8% (95%CI, 0.05–0.10)).

CONCLUSION

In summary, this systematic review provides insights into the mental health symptoms of HCWs during the COVID-19 pandemic. This review has summarized relevant literature pertaining to the mental health of HCWs during a pandemic and suggests future research directions. It is now evident that COVID-19 has a viable impact on HCWs in terms of their mental health. In particular, researchers need to investigate the mental symptoms experienced by respiratory therapists. Furthermore, they must focus on HCWs working in overlooked countries (i.e., Jordan, Iraq, Lebanon, and Syria). Finally, management in healthcare settings (i.e., hospitals) should apply effective strategies to improve the psychological symptoms among their healthcare workers.

AVAIALABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

All the data and supportive information are provided within the article.