All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Conceptual Framework for the Psychosocial Management of Depression in Adolescents in the North West Province, South Africa

Abstract

Background

A conceptual framework is imperative in the understanding of the psychosocial management of depression in adolescents, owing to the ability to effectively present and demonstrate the linking of concepts for an in-depth understanding of the phenomenon.

Objectives

This study aims To develop and validate a conceptual framework for the psychosocial management of depression in adolescents in the North West Province, South Africa.

Methods

A qualitative, exploratory, descriptive, contextual research design was followed in two phases: the empirical phase (phase 1) and the development of a conceptual framework phase (phase 2). Phase 1 consisted of two steps: firstly, a systematic review (referred to as step 1), followed by qualitative, exploratory, descriptive, and contextual research (referred to as step 2). The outcomes from the empirical phase served as the foundation for developing a conceptual framework for the psychosocial management of depression in adolescents, North West Province, South Africa. In Phase 2, the development of this conceptual framework was guided by addressing the six crucial questions introduced by Dickoff et al. (1968) regarding Practical Orientation and validated by Chinn and Kramer’s five criteria questions.

Results

The conceptual framework focused on mental health practitioners, immediate and extended family members of adolescents, social workers, psychologists and peer groups of adolescents, adolescents diagnosed with depression, mental health institutions, homes of adolescents, schools, religious institutions, and communities.

Conclusion

The conceptual framework for the psychosocial management of depression in adolescents provides comprehensive insights capable of enhancing the recovery process for adolescents dealing with depression. Implementing this conceptual framework has the potential to enhance professional practice, elevate the quality of care provided, and contribute to expanding the body of knowledge within the field of mental health.

1. INTRODUCTION

A conceptual framework functions as a comprehensive system of interconnected concepts, promoting a more profound comprehension of a given phenomenon [1, 2]. These interlinked concepts not only support each other but also represent diverse phenomena, providing a broader perspective of the underlying ideology [3]. Various definitions of a conceptual framework converge on the idea that it constitutes a plan, network, or an interlink of concepts that help in comprehending the knowledge underlying a phenomenon [4, 5]. While denoting the linking of concepts, a conceptual framework is, in essence, a construct composed of consistent concepts that play pivotal roles in the overall understanding of a phenomenon [6]. Therefore, a well-constructed conceptual framework plays a crucial role in organizing and implementing interrelated concepts relevant to a phenomenon [7, 8]. The process of developing an effective conceptual framework entails careful integration of concepts related to the phenomenon, with a focus on explicating the connections between them [9]. In the context of this study, we utilize a conceptual framework to establish links among concepts derived from themes in previous studies concerning the psychosocial management of depression in adolescents. The aim is to foster effective mitigation of depression among this vulnerable group in the North West Province, South Africa. This conceptual framework forms an essential foundation for comprehensively understanding the psychosocial management of depression in adolescents [10], providing a clear presentation and demonstration of the interlinked concepts [1]. Psychosocial management encompasses psychological and social programs designed to offer problem-solving therapy, community support, and psychoeducation to mental health care users, including adolescents suffering from depression [11]. As a global public health concern, depression in adolescence poses significant challenges to mental health practitioners, especially nurses [12-14]. The prevalence rate of depression among adolescents aged 13 to 18 years stands at 5.6%, with an estimated 8 to 21% of adolescents affected before the age of 18 years [15, 16]. The 2018 report by the South African Depression and Anxiety Group [17] during Teen Suicide Prevention Week in February emphasized a significant link between depression and suicide, accounting for up to 9% of all deaths among adolescents in South Africa. Further, a previous study [18] highlighted the prevalence of depression among South African adolescents, ranging from 4 to 8 percent, with common symptoms such as poor self-esteem, sadness, mood, irritability, withdrawal, and poor concentration. Additionally, a Mercury survey in June 2018 focused on South African youth in grades 8 to 11 in Durban, revealing that approximately 21% of participants had experienced depression. Another survey in the metropolitan area of Cape Town indicated a higher percentage of 41% of young people aged 14 to 15 years suffering from depression. Notably, these findings exceed the report by Paruk and Karim, which noted that 21% of adolescents had attempted suicide due to depression at some point [19, 20]. Moreover, according to a previous study [21], a notable yearly occurrence of 20% of depression is documented in South African adolescents, as indicated by the national representative study conducted by the South African Stress and Health (SASH) survey. To provide more detailed insights, the Western Cape registers an approximate depression rate of 15-17% in adolescents. In contrast, the North West Province (NWP) shows prevalence figures of 7.45% within its rural communities and 18.6% among its urban population. These statistics underscore the urgent need for concerted efforts to provide evidence-based psychosocial management measures to address depression in this vulnerable population effectively.

In South Africa, the National Mental Health Policy Framework and Strategic Plan (2013 – 2020) addresses mental health for children and adolescents at various healthcare levels. However, it provides limited attention to the psychosocial management of depression among adolescents. Moreover, the South African Policy Guidelines for Child and Adolescent Mental Health focuses on general and specific mental health interventions but lacks a distinct emphasis on the psychosocial management of depression in adolescents [22, 23]. It is worth noting that mental health care providers, including mental health nurses, in the North West Province of South Africa must prioritize the use of evidence-based psychosocial interventions to address depression among adolescents [24]. In South Africa, mental health nurse practitioners encounter several obstacles, which encompass insufficient expertise and proficiency in managing mental health issues such as adolescent depression [25, 26]. As argued by [10], mental health nurses often lack sufficient psychosocial management approaches to effectively address depression in adolescents, leading them to rely on other professionals, such as clinical psychologists. Notwithstanding, a collaborative approach among healthcare professionals is essential in managing mental health conditions, making adequate psychosocial management of depression crucial for mental health nurses, particularly in the North West Province, South Africa [10]. The value of psychosocial management in the treatment of depression among adolescents is evident because mental health nurses usually serve as the primary point of contact for individuals seeking assistance in mental health facilities and departments [27]. However, the comprehensive search for available mental health frameworks for children and adolescents in South Africa conducted by [27] revealed major gaps, including the absence of a publicly available framework and significant shortcomings in psychosocial management policies. Consequently, providing mental health nurses with a comprehensive approach to managing depression among adolescents, especially in the North West Province, South Africa, becomes crucial. The need for evidence-based psychosocial management of depression in adolescents has been emphasized in the literature [28, 29]. Interestingly, the literature review conducted for this study unveiled the absence of an existing conceptual framework for the psychosocial management of depression in adolescents in the North West Province, South Africa. Recognizing this gap, the researchers determined the importance of developing and validating a conceptual framework for the psychosocial management of depression in adolescents, as undertaken in this study. Thus, the central question guiding this study is, “How can a conceptual framework for the psychosocial management of depression in adolescents be developed and validated?”

2. METHODS

2.1. Purpose of the Study

This study aimed to develop and validate a conceptual framework for the psychosocial management of depression in adolescents in the North West Province, South Africa.

2.2. Study Setting

The study was carried out at two outpatient units in two mental health care institutions in Dr. Kenneth Kaunda and Ngaka Modiri Molema districts of the North West Province of South Africa, as well as two mental health care facilities within two general hospitals in the Bojanala and Dr. Ruth Segomotsi Mompati districts. Adolescents, parents, and mental health nurses were the study's purposefully selected participants. The researchers selected adolescents in the age range of 14 to 17 years (both girls and boys) as the ideal participants for this study due to their ability to provide coherent responses and valuable data to address the research questions.

Additionally, the study encompassed individuals falling within the specified age category for adolescents as outlined in the Demographic Profile of Adolescents in South Africa (DPA). Furthermore, adolescents who had been diagnosed with depression but were in the period following their discharge, where they were not receiving active treatment, were included as they were less likely to experience symptoms that could interfere with their ability to answer the research questions. Non-psychotic adolescents who were receiving treatment for depression in mental health care institutions or units were also selected as they were more likely to provide meaningful responses to the research questions. English Language or Setswana-speaking ability was a requirement for participation. The research also included parents of adolescents who were either undergoing treatment for depression or accompanying the adolescents to outpatient appointments for mental health assessments. This inclusion was based on their crucial role as primary caregivers. Parents bear the responsibility of providing emotional support, food, shelter, guidance on behavior, and spiritual counseling to the adolescents. The study chose nurses who had been employed for at least five years in mental healthcare facilities and units and who were either male or female. English or Setswana-speaking nurses were included, and all were certified mental health (psychiatric) nurses registered with the South African Nursing Council (SANC).

2.3. Research Design and Methodology

This study comprised an empirical phase (phase 1) and the development of a conceptual framework phase (phase 2). A qualitative, exploratory, descriptive, contextual research design, as explained in previous studies [30, 31], was followed in developing a conceptual framework for the psychosocial management of depression in adolescents in the province. Phase 1 consisted of two steps, namely, a systematic review (step 1) and qualitative, exploratory, descriptive, and contextual research (step 2) [32, 33]. Step 2 was further divided into two stages, with participants purposefully sampled and data collected through interviews with parents and adolescents and focus group discussions with mental healthcare nurses. This research design allowed the researchers to collect in-depth information during phase 1 that was used for the development of the conceptual framework for the psychosocial management of depression in the study context. Phase 2, dedicated to the development of the conceptual framework, was facilitated by addressing the six crucial questions of a study [34], with Practical Orientation-

Who is the agent of the framework? Who is the recipient of the framework?

In which context will the framework be implemented? How will the framework be implemented (Procedure)? What are the dynamics of the framework, and what will be the endpoint of the framework?

2.3.1. Phase 1: The Empirical Phase

The empirical phase consisted of two steps: a systematic review followed by qualitative, exploratory, descriptive, and contextual research.

2.3.1.1. Step 1: Systematic Review

A systematic review was used to gather quality evidence about the psychosocial management of depression in adolescents, with special emphasis on resilience and help-seeking behaviours. With the assistance of a librarian at the North-West University (Mahikeng Campus), articles from January 2013 to June 2019 were searched in the following databases: “EBCOHOST”; “Emerald Insight”; “ScienceDirect”; “Sabinet Online”; and “Scopus” using the following keywords: “psychosocial or social and psychological management,” “adolescent or teenage depression,” “resilience” and “help-seeking behaviours.” The inclusion criteria included quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods research that was published between 2013 and 2019 on the psychosocial management of depression in adolescents with particular emphasis on resilience and help-seeking behaviours and studies published in the English Language. Studies excluded include those conducted before 2013 that do not focus on psychosocial management of depression in adolescents, including confirmatory, duplicates, replication studies, and newspaper articles. The search identified 1515 articles that were scrutinized based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria of the study, with six articles accepted for review. The critical appraisal developed and embedded in the Johns Hopkins Nursing Evidence-Based Practice Research Evidence Appraisal Checklist was used to ensure the authenticity of the search [35]. Furthermore, a critical appraisal of the findings was done by an independent person, ensuring the use of ethically validated articles that met the inclusion criteria of the systematic review and reached a consensus with the researchers. Two distinct themes emerged from the systematic review including protective factors relevant to managing depression in adolescents and support systems for resilience and help-seeking behaviours.

2.3.1.2. Step 2: Qualitative, Exploratory, Descriptive, and Contextual Research were Used in Two Separate Stages

Tech’s open coding approach was used to analyze the data collected at both stages of this step [31]. Stage 1: The purpose of this stage was to explore and describe the experiences of adolescents and parents with the current management of depression among adolescents. Semi-structured individual interviews were conducted with 18 purposively selected adolescents (14 females and 4 males) and 14 parents (13 females and 1 male). The adolescents were aged between 14 and 17 years. Two themes emerged from this stage, includng negative experiences regarding depression among adolescents and the management of depression in adolescents.

2.3.1.3. Stage 2

The purpose of this stage was to explore and describe the perceptions of mental health nurses regarding the psychosocial management of depression in adolescents. Participants were purposively selected. Four focus group discussions were conducted with 18 mental healthcare nurses. Three of the groups had five participants each, while one of the groups consisted of only three members because of the limited number of nurses working in the unit. The point of data saturation was observed in the 2 stages.

Two themes emerged from this stage, including comprehensive psychosocial management; and the involvement of different stakeholders.

2.4. Participants Recruitment

The recruitment of adolescents and parents was facilitated by professional nurses working in the study areas because they understand the signs and symptoms presented by adolescents visiting the outpatient department. The professional nurses identified the adolescents during their follow-up visits, excluding those with psychotic conditions. They then approached the parents of these adolescents, informed them about the study, and sought their permission to take part in the study and to approach the adolescents for them to also participate in the study. Permission was obtained from the parents before approaching the adolescents because they were in minority and a vulnerable group. Hence, permission was required from parents before they participated in this kind of research. The professional nurses referred the interested adolescents and parents to a negotiator who is a postgraduate student in nursing, to make an appointment for the signing of permission and the voluntary informed consent forms. Parents of adolescents signed a permission form permitting their children to take part in the study. Parents also signed voluntary informed consent forms, which permitted them to participate in the study. The mental healthcare nurses were recruited by the administrative officers working in each of the study areas because of issues of power relations, while the negotiators facilitated the signing of voluntary informed consent forms.

Permission was sought and obtained from the participants to use a tape recorder during the data collection sessions. Additionally, a translator was engaged during the data collection and signed a confidentiality agreement form. The data was collected in English, but a translator was used for one participant who responded to questions in the Setswana language. The recruiter thoroughly explained the study’s purpose, including the benefits and risks involved, to allow them to make informed decisions. The researcher who collected the data reminded the participants that they were free to withdraw from the study at any point without any penalty. Confidentiality and anonymity were maintained by assigning pseudonyms to participants. The principle of beneficence was adhered to during the focus group discussions and interviews by ensuring all participants were comfortable with the group rules and respect of persons. The collected data were analyzed by the researcher, and an independent coder, and an agreement was reached on the generated themes and categories. The money spent by the participants for calling the negotiator to declare their interest was reimbursed to them.

2.5. Trustworthiness

Trustworthiness in the study's empirical phase was ensured through credibility, dependability, confirmability, and transferability [35, 36]. Credibility was ensured by consulting relevant databases and validating the conceptual framework with stakeholders. The conceptual framework was developed and validated under the supervision of the promoters, who were experts in the development and validation of frameworks. Transferability was ensured through detailed descriptions of methods and results.

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The results of the study were presented and discussed according to the empirical and development phases.

3.1. Converging Results of the Empirical Phase

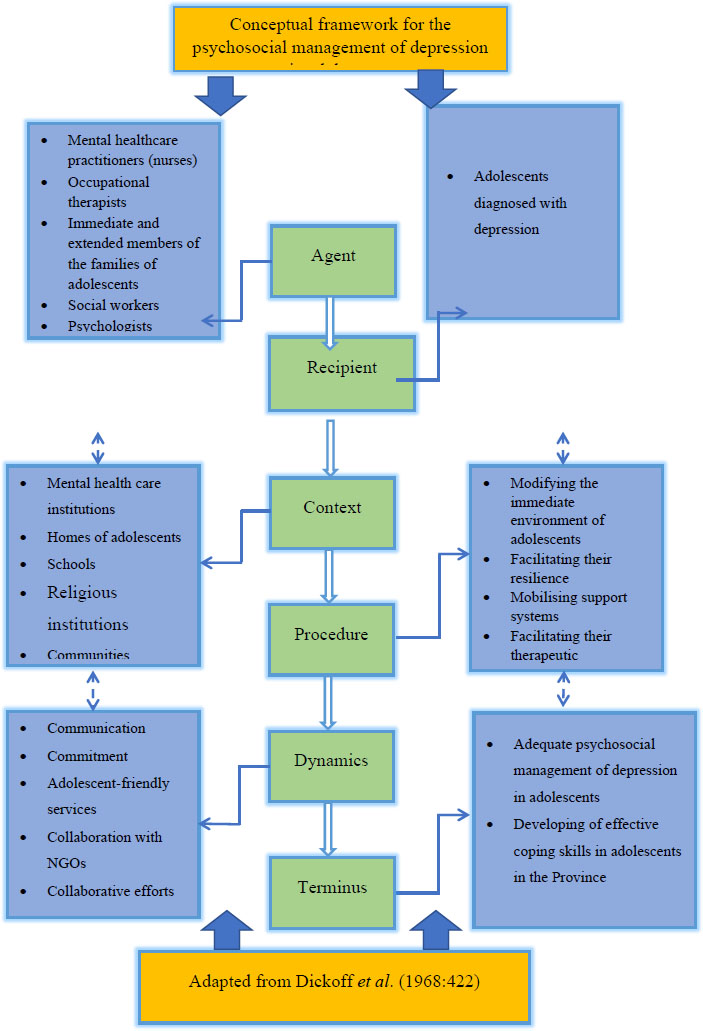

The empirical phase started with a systematic review of the psychosocial management of depression in adolescents, with an emphasis on resilience and help-seeking behaviours. Two themes emerged from the systematic review, including protective factors relevant to managing depression in adolescents and support systems for resilience and help-seeking behaviours [37]. Secondly, the experiences of adolescents and parents with the management of depression among this age group were explored and described (Fig. 1).

Two themes surfaced, namely, negative experiences regarding depression among adolescents; and methods of managing depression in adolescents [38]. Lastly, the empirical phase was used to explore and describe the perceptions of mental health nurses on the psychosocial management of depression in adolescents. Two themes emerged: comprehensive psychosocial management; and the involvement of different stakeholders [39]. The results of the empirical phase served as the basis for developing a conceptual framework for the management of depression in adolescents in the North West Province.

A conceptual framework for the psychosocial management of depression in adolescents, North West Province, South Africa.

3.2. Phase 2: Development of a Conceptual Framework

Results of the empirical phase were merged to develop and validate a conceptual framework for the psychosocial management of depression in adolescents in the province. As recommended by a previous study [2], the themes were organized in a precise manner to develop and validate the conceptual framework. Thus, concepts were deduced from the themes and categories of the empirical phase by answering the six Practical Orientation Theory questions proposed by [34]. The questions are as follows:

1) Who is the agent of the framework (Agent)?

2) Who is the recipient of the framework (Recipient)?

3) In which context will the framework be implemen-ted (Context)?

4) How will the framework be implemented (Proce-dure)?

5) What are the dynamics of the framework (Dyna-mics)? and

6) What will be the endpoint of the framework (Ter-minus)?

3.3. Description of the Structural Presentation of the Conceptual Framework

Fig. (1) provides a description of the conceptual framework for the psychosocial management of depression in adolescents in the NWP SA in accordance with the concepts provided by [33]. The process started with the “Agent”, which is the first small-sized rectangle with a green accent, and lighter colour, and down to the “Terminus”, which is the last among the six concepts [33]. There are various linking elbow arrows from each of the six concepts of [33] linked to blue square-shaped diagrams at each side of the conceptual framework, presenting the essential concepts of the conceptual framework.

Converging results of the empirical phase

3.4. Relevance and Objectives of the Conceptual Framework

The conceptual framework facilitates the under-standing of the psychosocial management of depression in adolescents in the province and provides clear information for the psychosocial management of depression in adoles-cents. The framework can improve professional practice and quality of care and benefit mental health care practitioners, families, secondary and high schools, peer groups of adolescents, religious institutions, governments and non-governmental organizations, stakeholders, policy-makers, and communities in general. Furthermore, the conceptual framework could be beneficial if included in the curriculum of undergraduate nursing students with broad and in-depth knowledge of the psychosocial management of depression in adolescents. In addition, adoption can improve professional practice and quality of care and add to the existing body of knowledge in mental health.

3.5. Assumptions of the Conceptual Framework

The assumption in this study refers to the perceived realities by which the conceptual framework is facilitated [40], which adds value to the conceptual framework. For effective psychosocial management of depression in adolescents, families (immediate and extended) of adolescents should understand the emotional difficulties associated with being an adolescent and be observant of the emotional challenges of the adolescents while providing the necessary support that could enhance their coping mechanisms. For families to understand depression, they need to pay attention to the emotional health of the adolescents and understand that every lived experience of an adolescent is unique. Furthermore, there should be positive support for adolescents, including their families, peer groups, communities, schools, religious institutions, mental healthcare institutions or mental healthcare practitioners, governments, and every non-governmental organization. The effective functioning of all these groups has the potential to influence the amelioration of symptoms of depression in adolescents and foster recovery. Considering the multifactorial causes of depression in adolescents, symptoms, and consequences to the adolescent, family, and society, the involvement of these groups is influential in the management of depression among this age group.

Responses to the six crucial questions proposed by [33] on Practical Orientation Theory are given below.

3.5.1. Agent: Who is the Agent of the Framework?

Agents of the framework [33], refer to persons who foster activities to ensure the effective psychosocial management of depression in adolescents. These agents have a direct impact on the mental health of adolescents by enabling adolescents suffering from depression to develop effective coping skills and relieve the mental health burden of depression on the individual, family, and society. Agents include mental healthcare practitioners, especially nurses, occupational therapists, social workers, psychologists, immediate and extended members of the families of adolescents, and peer groups of adolescents. Agents such as mental healthcare nurses, who are the first line of healthcare managers in different mental health institutions or units, should ensure user-friendly services for adolescents, prioritize the provision of adequate therapeutic environments, continuously monitor their mental health, and provide a comprehensive support system. Adolescents can easily feel disappointed when services do not favour them and feel judged by caregivers, leading to neglect in consulting or visiting healthcare facilities. Mental healthcare nurses should also implement follow-up measures for adolescents discharged from these facilities. The welfare of adolescents after discharge from mental health institutions should be prioritized through follow-up to continue adhering to health counseling or recovery guidelines, which will foster mitigation of relapse. Occupational therapists are expected to facilitate the development of coping skills for recovery. They can assist adolescents in incorporating sensory and movement to enhance attention and learning while working with mental healthcare nurses, schools, and other stakeholders.

Furthermore, agents, such as members of the family (parents, siblings, and relatives), are expected to understand the emotional challenges of adolescents and support them in every capacity, encourage them, and provide counseling, where necessary, and basic needs. A conducive family environment facilitates a reliable coping resource that can foster recovery from depression. Family involvement in the management of depression is crucial due to the motivational roles played by parents in the treatment process. Parents mostly motivate the treatment of children [41] and influence the degree to which adolescents respond to emotional challenges, balance, and recovery from mental health conditions, such as depression [42].

Psychologists should be readily available at mental healthcare institutions and units while working together with other mental healthcare practitioners in developing adequate coping skills that can facilitate their recovery from depression. Social workers should be actively involved in identifying depressed adolescents in families and communities, providing healthcare education to such adolescents and their families in order to foster effective coping skills. They should also provide emotional support to depressed adolescents and their families and carry out follow-up management of such adolescents. Social workers are important in providing psychosocial care for adolescents with depression [43].

Peers communicate in the language. They understand better, learn from each other, and support one another when necessary. The communication and support system from peers facilitates the development of coping skills in adolescents with depression. Thus, peers should be educated on depression by educators in schools, social workers in society, religious leaders, and knowledgeable family members and encouraged to actively participate in supporting one another, especially during depression, to foster recovery. An adolescent can have low esteem yet pretend to be confident. Hence, adolescents should be encouraged to speak out about their emotional challenges and be supportive of each other. Adolescents spend more of their time with their peers than parents, where they develop emotional socialization and become agents for the facilitating of supportive emotional socialization [44].

3.5.2. Recipient: Who is the Recipient of the Framework?

Recipients are adolescents diagnosed with depression. Adolescence is a vulnerable stage of development in an individual, characterized by changes in body image, emotions, initiation of relationships with peers, and many more [38, 45]. Hence, adolescents are predisposed to different psychological issues that can alter their coping threshold [39]. Depressed adolescents should be embraced and provided the necessary support to help mitigate relapse and foster recovery. Mental healthcare practitioners, families, and society should not stigmatize adolescents suffering from depression. They should be assisted in being resilient and coping with their recovery.

3.5.3. Context: In which Context will the Framework be Implemented?

Context is the environment in which all processes of the psychosocial management of depression in adolescents will occur in the North West Province. Psychosocial management will be implemented within a context by an agent and received by the recipient, that is, adolescents diagnosed with depression. The context includes the following: mental healthcare institutions, homes of adolescents, schools, religious institutions, and commu- nities. These contexts are the major role players on which other concepts are dependent for the psychosocial management of depression in adolescents.

3.5.4. Procedure: How will the framework be implemented (Procedure)?

The procedure in the development of a conceptual framework involves steps to be taken to ensure success in the psychosocial management of depression in adolescents. The procedure followed two steps:

3.5.4.1. Step 1: Modifying the Immediate Environment of Adolescents in Order to Foster Recovery and Develop Effective Coping Skills

Modifying the immediate environment of adolescents can be fostered through collaborative care in mental healthcare institutions or mental healthcare units, homes, schools, peer groups, religious institutions, and communities. The units in the immediate environment should understand the concept of the “adolescent stage,” challenges faced by adolescents, daily depression in adolescence, and the devastating consequences on the individual, family, and society. The units should endeavor to understand their various roles toward achieving the common goal focused on ameliorating symptoms of depression, fostering recovery, and enabling the adolescent to develop effective coping skills. Furthermore, training should be given to stakeholders regarding the management of depression in adolescents to ameliorate its symptoms and foster recovery. All collaborating units or stakeholders should work harmoniously to monitor and evaluate the progress of recovery through follow-up. In addition, there should be provision of necessary resources to concerned units to foster adequate delivery of mental health care to depressed adolescents.

3.5.4.2. Step 2: Facilitating Resilience in Order to Foster the Development of Effective Coping Skills

Facilitating resilience is important as depression in adolescents affects the emotional stability of the person, self-esteem, and coping skills. The process of facilitating resilience can be obtained through health talks at schools and the distribution of pamphlets with summarised information on resilience and counseling. Furthermore, educator training on managing depression in adolescents and the importance of resilience in religious institutions and communities can be beneficial. This requires health education for adolescents, encouraging positive help-seeking behaviours through radio and television broadcasts, and providing therapeutic environments for adolescents with depression. Social media can be used to disseminate information on the development of resilient attitudes. In addition, continuous monitoring of the recovery process by mental healthcare nurses and ensuring effective delivery of mental health services in primary healthcare settings could be helpful to adolescents with depression.

Facilitating resilience can be obtained through posters on subways, displaying information regarding overcoming depression in adolescents, and encouraging peer education. There is also a need to ensure an encouraging atmosphere in families where adolescents can air their opinions, parental role modeling, listen to adolescents’ emotional problems, and encouraging help-seeking behaviours. Physical exercise by adolescents, parental emotional support, social support, and healthy relationships enhance resilience to mental health conditions, such as depression in adolescents [46].

3.5.5. Dynamics: What are the Dynamics of the Framework?

Dynamics denotes the power sources, which can be agents, recipients, or part of the context that fosters the development of the conceptual framework. The power sources for the conceptual framework include communi- cation, commitment, friendly mental healthcare services for adolescents, collaboration with NGOs, collaborative efforts, and involvement of relevant stakeholders. Power sources are expected to engage adolescents suffering from depression appropriately and their families in a therapeutic communication milieu in order to facilitate the psychosocial management of depression. Thus, there is a need for adequate communication, commitment, friendly mental healthcare services for adolescents, and collaborative efforts of NGOs with religious leaders and necessary stakeholders in society, such as mental health policymakers, having a common goal and objectives directed towards enhancing the recovery of depressed adolescents. The collaborative efforts of these power sources are important in performing and sustaining the psychosocial management of depression in adolescents. The effective functioning of the various units of this power source is important in fostering positive help-seeking behaviours, mitigation of symptoms of depression in adolescents, enhancing recovery, and developing effective coping skills.

3.5.6. Terminus: What will be the Endpoint of the Framework?

The terminus denotes the end point of the conceptual framework that will enable adolescents to develop effective coping skills and ensure adequate psychosocial management of depression in adolescents. Implementation of the developed conceptual framework by agents or stakeholders can promote the management of depression in adolescents.

3.6. Validating the Conceptual Framework

Mental health care nurses, adolescents, parents, and experienced researchers participated in validating the conceptual framework by responding to the framework validation criteria questions proposed by [47]. The mental healthcare nurses had five years of work experience in the research setting. Adolescents who validated this conceptual framework were aged 14 to 17 years, diagnosed with depression and non-psychotics, and visited the hospitals three weeks after discharge for check-ups. Parents refer to the biological parents of the adolescent or any relative who accompanies the individual to the mental healthcare institution or mental healthcare units for check-ups. Research experts were professors in the School of Nursing Science.

The critical reflection questions proposed by [47] were:

1. How clear is the framework?

2. How simple is the framework?

3. Could the concept be generalised?

4. How accessible can the framework be? and

5. How important is the framework?

The conceptual framework and validation tool, containing the critical reflection questions proposed by Chinn and Kramer, were disseminated among mental healthcare experts (mental health nurses and psychologists), experienced researchers, parents, and adolescents containing the critical reflection questions proposed by [47]. The validators responded to the questions with recommendations. The recommendations were integrated into the framework for clarity.

3.7. How Clear is the Framework?

Participants found the framework clear and understandable due to its detailed elaboration and practical language. Mental health nurses, psychologists, parents, and adolescents all agreed on its clarity.

3.8. How Simple is the Framework?

The framework was deemed simple, featuring clear diagrams and straightforward language. Participants, particularly parents and mental health nurses, appreciated its ease of understanding.

3.9. Could the Conceptual Framework be Generalized?

Participants agreed that the framework could be generalized beyond the study area, given its relevance to various settings and populations.

CONCLUSION

The conceptual framework consists of vital information on the psychosocial management of depression in adole- scents, such as agents, recipients, context, procedures, dynamics, and terminus. Relevant stakeholders validated the conceptual framework. The validators confirmed the relevance of the framework. The conceptual framework contributes new and comprehensive knowledge that can improve professional practice and quality of care.

LIMITATIONS OF THE STUDY

While the study was limited to the North West Province, the development and validation of the conceptual framework were based on a qualitative approach to inquiry. Thus, its findings hold relevance for broader contexts. Additionally, the process of developing and validating the conceptual framework was described in detail with comprehensive information for the audience.

RECOMMENDATIONS

It is recommended that the framework be adopted and implemented by all stakeholders in different contexts, such as mental healthcare institutions, social workers, schools, religious institutions, and communities in the province. It is imperative to prioritize the mental health of adolescents because the future is in their hands.

DECLARATIONS

The Department of Health in the North West Province further gave permission for the study to be conducted. Permission was also obtained from the Chief Executive Officers (CEOs) of the two mental health care institutions in Dr. Kenneth Kaunda and Ngaka Modiri Molema districts in the NWP, SA, and two mental health care units attached to two general hospitals in Bojanala and Dr. Ruth Segomotsi Mompati districts in the province.

AUTHORS' CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors contributed equally to the manuscript to merit authorship.

ABBREVIATION

| DPA | = Demographic Profile of Adolescents in South Africa |

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

The study was approved by the Scientific Committee of the School of Nursing Science (SONS) and the North-West University (NWU) Faculty of Health Sciences Health Research Ethics Committee (NWU-HREC Reference Number: NWU-00448-19-A1).

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of institutional and/or research committees and with the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki, as revised in 2013.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Parents of adolescents signed a permission form giving permission for their children to participate in the study. Parents also signed voluntary informed consent forms, which permitted them to participate in the study.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

The data set used in the study is not in any repository, rather the data are available from the corresponding author [P.C] upon reasonable request.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors express their appreciation to the management of all study areas by approving the study's conduct in the facilities. They would also like to thank all adolescents, parents, and mental health nurses who participated in the study. Furthermore, the authors extend their gratitude to Dr. PN Nkamta for taking the time to edit the paper in a language appropriate to their own.