All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

The Relationship between Quality of Work Life and Post-traumatic Stress Disorder in Nurses during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-sectional Study

Abstract

Introduction

In the midst of the global pandemic, nurses were confronted with numerous challenges that put them at risk of developing Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). These challenges arise from the high mortality rates among patients and the diminished quality of life caused by overwhelming workloads.

Aim

The researchers conducted a study aimed at determining the relationship between the quality of work life and PTSD nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted in Mashhad in 2021. The study sample consisted of 180 nurses working in hospitals admitting patients. The research instruments encompassed a demographic information form, the quality of work-life questionnaire with three sub-domains of compassion fatigue, burnout, and compassion satisfaction, and the post-traumatic stress disorder questionnaire. Data were analyzed using SPSS-25 software.

Results

Among the participating nurses, the mean and standard deviation of compassion fatigue, burnout, and compassion satisfaction scores in nurses were 24.16 ± 6.77, 25.26 ± 6.09, and 27.42 ± 6.51, respectively. Additionally, the mean score for stress following critical incidents was determined as 42.31 ± 8.71. Spearman's correlation test revealed a significant and positive relationship between the PTSD score and compassion fatigue within this sample.

Conclusion

The results indicated a positive correlation between the decrease in the quality of work life and PTSD. These findings contribute to a better understanding of effective strategies for promoting mental well-being and identifying key aspects to be measured in future interventions. Moreover, these results can guide the development of targeted mental health management interventions aimed at supporting nurses in their vital work during major health crises.

1. INTRODUCTION

Over the past few years, a surge of novel viral illnesses has emerged, posing significant risks to public health worldwide. Among these threats, the pandemic caused by the COVID-19 virus stands out as the most critical health crisis in recent times [1-3].

The healthcare community was confronted with unprecedented and distressing circumstances during this pandemic. Confronting an unknown disease like COVID-19 subjected these individuals to immense stress, resulting in adverse effects on their mental well-being [4, 5]. Throughout this crisis, healthcare workers faced constant pressures arising from heavy workloads, insufficient time for recovery, inadequate hospital resources, and sepa- ration from their loved ones [6, 7]. Such intense pressure not only impacts the decision-making capacity of the medical staff but also leaves lasting effects on their overall state of wellness [8, 9]. Additionally, these factors can occasionally compromise the quality of patient care and contribute to severe physical and mental exhaustion [10, 11]. Therefore, these challenges caused greater physical and psychological difficulties than previous public health crises [12, 13].

One crucial aspect of Quality of Work Life (QWL) is the sense of psychological, physical, and occupational safety within the workplace [14, 15], as it significantly influences employee satisfaction and their decision to stay or leave their jobs [16]. Quality of Work-Life (QWL) is the main requirement for the empowerment and performance of nursing professionals in healthcare systems [2, 17]. Lack of opportunities for professional advancement, inadequate salaries, poor communication with colleagues, and an unsuitable work environment are the main reasons for poor QWL in nursing [18-20]. During this prolonged crisis, medical personnel experienced varying degrees of job burnout, which directly impacted the quality of their work [21]. In other words, the quality of work-life also plays a vital role in patient care and nurse engagement, and factors, such as stress, fatigue, and high workload can severely undermine the overall well-being and resilience of nurses [22, 23]. Nanjundeswaraswamy et al. (2023) reported in their study that work conditions, work environment, work-life balance, compensation and reward, career development, job satisfaction and security, organizational culture, relationships among coworkers, and stress all affect the quality of work life of nursing staff [24]. The high quality of work-life is the basic ground for empowering the human resources needed by health systems; therefore, it is necessary and vital to pay attention to the quality of work-life of nurses, who are the largest part of health systems employees. Hence, under- standing and, as a result, improving the quality of work-life in nursing is an important factor in achieving high levels of quality of care [25].

Literature addressing attrition from the nursing workforce highlights the influence of the work environment on decisions to stay in the profession. Difficult work environments increase the likelihood of stress, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and burnout [26, 27]. Work conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic underwent significant change. A systematic review identified that psychological issues were prevalent in healthcare workers during the pandemic, with physicians and nurses in particular likely to suffer from depression, anxiety, insomnia, PTSD, and stress [28]. Pandemic-related work conditions, such as increased working hours, redeployment and caring for COVID-19 patients, were repeatedly associated with mental health disorders and intention to leave [29].

Nurses, due to their exposure to traumatic situations while caring for patients, are at risk of developing PTSD [30, 31]. The findings from the study conducted in Italy by Naldi et al. during the COVID-19 epidemic are concerning. They reported that one-third of the sampled individuals experienced severe anxiety and distress, with 60% of nurses reporting posttraumatic stress symptoms and approximately 41% experiencing severe emotional fatigue [32]. In the study of Andhavarapu et al. (2022), the findings showed that factors, such as working in the isolation ward and observing the death of patients, experiencing quarantine, and low level of nurse staffing had an effect on the level of PTSD of nurses caring for patients with COVID-19 [33]. Fateminia et al. (2022) reported that PTSD is common among nurses during a health crisis, such as Covid-19. PTSD can lead to long-term burnout [34]. Moreover, nurses run a high risk of PTSD as frontline personnel in the battle against COVID-19, who are exposed to stressful working conditions and constantly witness death and trauma with so many patients [35].

The interplay between compassion fatigue and PTSD during the pandemic is crucial to understand, as healthcare workers are vulnerable to both conditions. Researchers recognize the importance of investigating the relationship between these two components during the current health crisis, aiming to develop effective strategies for mitigating their impact. The quality of nursing work life provides direct and more useful feedback for leaders who are interested in managing employees and achieving organizational results. However, the literature review results showed that few studies had examined the quality of work-life of nurses during the outbreak of COVID-19. Therefore, the current researchers set out to determine the relationship between the quality of work life and PTSD in nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Study Design

This cross-sectional descriptive study was conducted from January to March 2021 among 180 COVID-19 ward nurses from three hospitals: Imam Reza (AS), Qaem (AS), and Shariati in Mashhad City, East Iran. In this study, nurses working in inpatient and special COVID-19 wards were included.

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

To be included in the study, participants had to meet specific criteria, including holding a bachelor's degree in nursing, having at least two months of experience in providing care to COVID-19 patients in inpatient settings, no history of traumatic incidents, such as the death of loved ones and accidents in the past six months, no history of psychological disorders and anxiety (In such a way that the participants expressed the above items by self-declaration and if they had, they were removed) [34], and giving consent to participate. Participants who had a history of COVID-19 infection were excluded from the research sample. It should be noted that any participants who did not complete the questionnaire were also excluded from the final analysis (more than 5% of questions).

2.3. Sample Size

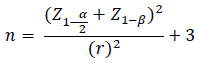

The current study aimed to examine the correlation between various factors among a sample of 180 nurses caring for COVID-19 patients in Mashhad in 2021. To ensure the validity of the research, a pilot study was conducted on 20 individuals before proceeding with the main study. The results of the pilot study helped estimate the appropriate sample size for the main study, which was determined to be 180 participants. Considering the correlation coefficient (r=0.22), the confidence percentage of 5%, and the Test power of 90%, the final sample size was calculated.

|

2.4. Data Collection

Upon receiving approval from the Ethics Committee at Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, the researchers proceeded to visit hospitals where COVID-19 patients were admitted. Following authorization from the hospital officials, the researchers visited the inpatient wards dedicated to COVID-19 cases. Initially, the study's objectives were explained to the nurses, and their verbal consent was obtained for their participation. Subse- quently, if the nurses met the inclusion criteria, they were provided with an informed consent form and questionnaires. A quota sampling method was employed to select participants from three hospitals: Imam Reza (AS), Qaem (AS), and Shariati. These hospitals were chosen as they provided specialized care for COVID-19 patients. Data collection in this study was done using a questionnaire.

2.5. Data Collection Tools

The measurement tools were a demographic information questionnaire, a quality of work-life question- naire, and a post-traumatic stress disorder questionnaire. A demographic information questionnaire was used to measure the basic information of nurses. This question- naire included information about nurses (age, gender, education level, marital status, work experience, number of shifts per month, working hours per month, department).

The professional Quality of Life Scale questionnaire (ProQOL) was used to measure compassion fatigue, burnout, and compassion satisfaction. It is a 30-item self-report scale that assesses the positive and negative aspects of auxiliary jobs. This scale consists of three subscales: compassion satisfaction (10 questions), burnout (10 questions), and compassion fatigue (10 questions). The options for each question are ordered according to the 6-part Likert scale from zero (never) to 5 (always). The range of items' scores is 0 to 50 in each of the subscales of compassion satisfaction, burnout, and compassion fatigue [36]. The total scores of the three subscales (compassion satisfaction, burnout, and compassion fatigue) are not summed to obtain a single total ProQOL score. Instead, they are used individually to assess the levels of each construct. The categorization of scores into low, moderate, and high levels is based on predetermined thresholds for each subscale. Compassion satisfaction, burnout, and compassion fatigue scores are grouped into three categories: low (22 points), moderate (23 to 41 points), and above (42 points). The validity of the questionnaire was previously confirmed, with a reported content validity index (CVI) of 0.84 [37]. The reliability of the questionnaire in the present study was obtained by calculating the internal consistency coefficient (Cronbach's alpha) with a value of 0.75.

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) was assessed using a 17-item questionnaire developed and validated by Weathers, Huska, and Keane (1991). The total PTSD score is derived from the sum of the 17 items, with scores ranging from 17 to 85. Higher scores indicate greater levels of PTSD. Each question is rated on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much). In a study conducted by Ebrahimpour et al. (2015), the validity of the PTSD questionnaire was established with a calculated value of 0.96 using the Content Validity Index (CVI) formula. Internal consistency was also determined, yielding a Cronbach's alpha coefficient of 0.86 for PTSD symptoms [38, 39]. In this study, the reliability of the questionnaire was calculated using the internal correlation coefficient (Cronbach's alpha) of 78%.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Data collected were analyzed using SPSS 25 software. Descriptive statistics, such as frequency, percentage, mean, and standard deviation, were employed to describe the data. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was utilized to assess the distribution of quantitative data. Spearman's correlation tests were conducted to explore the relationship between the two primary variables, while linear regression was employed to identify predictive factors. A significance level of less than 0.05 (p < 0.05) was considered statistically significant.

3. RESULTS

In this study, 180 nurses participated. The majority (56.7%) were women. The mean and standard deviation of the age and work experience of the nurses were 30.55 ± 6.23 and 6.60 ± 5.75 years, respectively. The mean and standard deviation of the number of duty shifts was 30.83 ± 6.89, and the duty hours per month were 168.89 ± 9.46 hours. Among the nurses, 109 (60.6%) worked in inpatient wards, 82.8% had a B.Sc., 74.4% worked rotating shifts, and 71 (39.4%) worked in special wards. Other demographic information is given in Table 1.

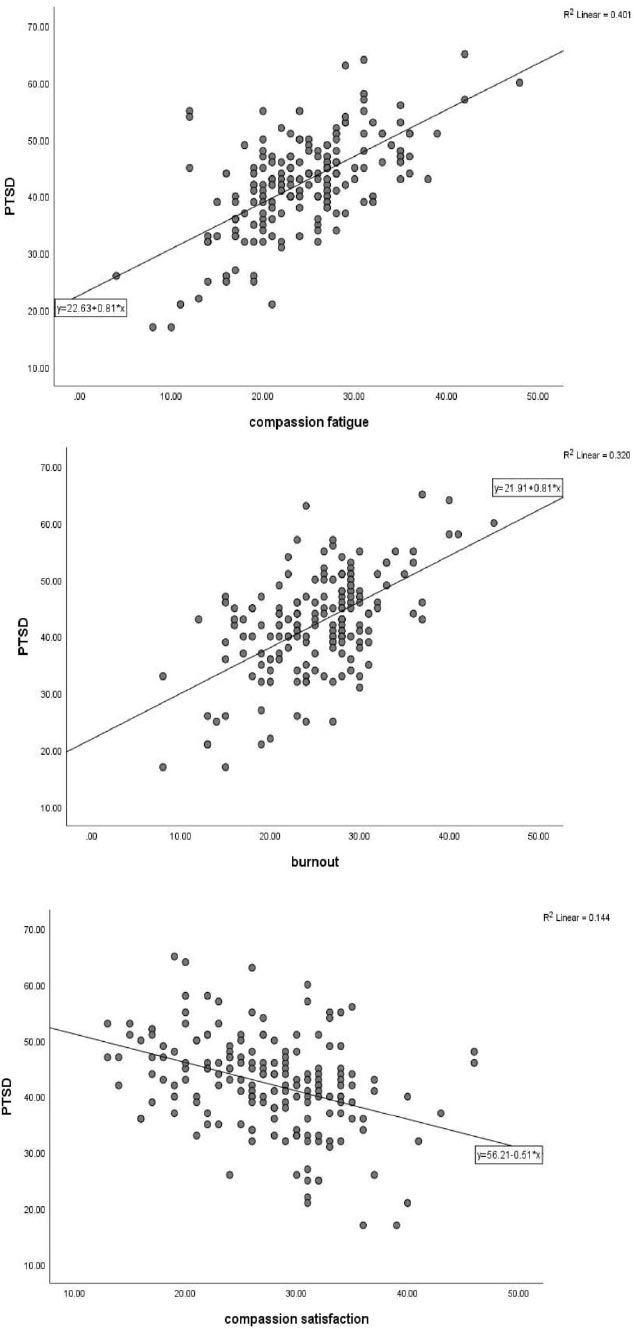

The mean and standard deviation of compassion fatigue, burnout, and compassion satisfaction in nurses were 24.16 ± 6.77, 25.26 ± 6.09, and 27.42 ± 6.51, respectively. Also, the mean and standard deviation of the PTSD score was 42.31 ± 8.71. Based on Spearman's correlation test, there was a direct and significant relationship between the PTSD score and compassion fatigue of this sample (Table 2 and Fig. 1).

| Variable | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | - | - |

| Male | 78 | 43.3 |

| Female | 102 | 56.7 |

| Level Of Education | - | - |

| B.Sc. | 149 | 82.8 |

| M.Sc. | 31 | 17.2 |

| Marital Status | - | - |

| Single | 99 | 55.0 |

| Marrried | 81 | 45.0 |

| Employment Status | - | - |

| Temporary | 87 | 48.3 |

| Contractual | 48 | 26.7 |

| Employment | 47 | 26.1 |

| Shift Type | - | - |

| Morning Shift | 10 | 5.6 |

| Afternoon Shift | 8 | 4.4 |

| Night Shift | 28 | 15.6 |

| Rotating Shift | 134 | 74.4 |

| Variable | Post-traumatic Stress Disorder | |

|---|---|---|

| r | P-value | |

| Compassion fatigue | 0.590 | <0.001 |

| Burnout | 0.482 | <0.001 |

| Compassion satisfaction | -0.377 | <0.001 |

| Model | Standard Coefficients Beta | t statistic | P-value | 95% Confidence Interval for B | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | ||||

| Compassion fatigue | 0.175 | 3.537 | 0.001 | 0.100 | 0.351 |

| Burnout | 0.204 | 4.581 | <0.001 | 0.166 | 0.416 |

| Compassion satisfaction | -0.164 | -4.054 | <0.001 | -0.325 | -0.112 |

| Gender | -0.202 | -4.523 | <0.001 | -5.075 | -1.991 |

| Age | 0.467 | 3.118 | 0.002 | 0.239 | 1.006 |

| Marital status | -0.064 | -1/615 | 0.108 | -2.467 | 0.246 |

| Work experience | -0.162 | -1.108 | 0.269 | -0.683 | 0.192 |

| Ward | 0.215 | 4.682 | <0.001 | 2.207 | 4.425 |

| Adjusted R2=0.735 | R2=0.747 | R=0.846 | |||

Through linear regression analysis, it was determined that factors, such as compassion fatigue, burnout, workplace environment, age, and gender significantly predicted PTSD. The model achieved a 74% accuracy rate in predicting PTSD (Table 3).

Examining the relationship between the quality of work life and PTSD.

4. DISCUSSION

The aim of this study was to determine PTSD and the quality of work-life in nurses involved in patient care during the COVID-19 crisis. The results showed a clear correlation between the experience of compassion fatigue and burnout in nurses who provide care for COVID-19 patients, along with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Conversely, there is an inverse relationship between compassion satisfaction and PTSD among these nurses. These psychological factors significantly impact the mental and physical well-being of nurses, as well as their job performance [40]. The results of the present study are consistent with some previous studies conducted on nurses [39, 41]. The psychological distress resulting from exposure to traumatic and stressful events can manifest in various ways, including symptoms, such as listlessness, distress, anger, dissociation, anxiety, and fear [42].

In Italy, a different study found that 60% of nurses experienced symptoms of PTSD, while nearly 41% suffered from severe emotional exhaustion [43]. Havaei et al. (2021) also reported high rates of PTSD (47%) and emotional exhaustion (60%) [44]. In line with our results, Hu et al. (2020) conducted a study with frontline nurses in China who were dealing with COVID-19. They found that these nurses experienced moderate burnout and a high level of fear. Additionally, half of them reported moderate to severe burnout, 60.5% experienced emotional exhaustion, and 42.3% reported depersonalization [45]. These findings align with previous studies conducted during the MERS and SARS epidemics [46]. Such cases can potentially develop into PTSD, leading to the emergence of PTSD symptoms in nurses [47]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, a sudden rise in the number of critically ill patients and the burden of decision-making affected stress and anxiety. Another study also found that nurses experienced higher levels of distress compared to physicians, possibly due to their closer and more frequent contact with COVID-19 patients [32]. Consistent with our findings, a systematic review conducted by D'ettorre et al. [48] recommended immediate interventions to safeguard healthcare workers from the traumatic effects of this pandemic. These symptoms of posttraumatic stress not only disrupt nurses' critical thinking abilities but also diminish their capacity for effective decision-making, ultimately impacting the quality of care they are able to provide [49]. These results clearly show the consequences of COVID-19 on HCWs’ health and efficiency. One of the most significant consequences of PTSD is its detrimental effect on other aspects related to the quality of work life. The quality of work life for healthcare personnel and nurses has been identified as a crucial factor in ensuring the sustainability of the healthcare system [50]. The levels of compassion fatigue, burnout, and compassion satisfaction were found to be moderate. Other studies have also highlighted the impact of the epidemic on increased burnout and compassion fatigue [36, 51]. These feelings in HCWs increase due to the nature of the work with patients with COVID-19, and the risk of infection while working in such departments, especially in ICUs, can cause burnout [52].

Only PTSD was found to have a positive and significant correlation with burnout, according to the results of the multivariate analysis. Previous research has consistently shown that PTSD can predict the occurrence of burnout [53, 54]. In addition to PTSD, other factors, such as long working hours, fear of infection, and perceived support, have also been identified as predictors of burnout components in various studies [55]. A study conducted by Zakeri et al. (2022) aligns with the present study, examining these variables during the COVID-19 pandemic [56]. Furthermore, it has been noted that the COVID-19 pandemic has heightened the risk and prevalence of nurses experiencing compassion fatigue, which can have adverse effects on patient care, the work environment, personal relationships, and overall mental health [57].

According to Restauri (2020), the heightened exposure to stress and trauma in different facets of life, such as the significant surge in workplace stress caused by the pandemic, could potentially amplify the occurrence of PTSD among physicians when coupled with burnout [58]. Prioritizing the quality of professional life for nurses can enhance their caregiving abilities, ultimately leading to improved and more effective nursing care. Therefore, the conditions of compassion fatigue, burnout, and compassion satisfaction serve as crucial components of professional life quality [59].

The COVID-19 pandemic had a moderate impact. Not only did the highly contagious disease raise concerns about physical health, but it also significantly affected the mental well-being of individuals in society, placing immense psychological pressure on various segments, particularly employees. According to Amiri et al. (2021), the COVID-19 pandemic had detrimental effects on both COVID-19 and burnout [60]. A report by Zeihar (2022) revealed that PTSD during the pandemic led to nearly 44% of nurses expressing a preference to leave their jobs [42]. Similarly, another study highlighted the negative influence of the pandemic on the PTSD of nurses, emphasizing the need for immediate measures and interventions [61]. Thus, a collaboration between nursing managers, healthcare organizations, policymakers, and researchers to comprehensively address compassion fatigue and PTSD is important. On the other hand, the need for continuous support systems and resources to promote mental well-being in nursing professionals is very significant.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the findings demonstrate a positive correlation between compassion fatigue and PTSD. This evaluation of nurses working during the COVID-19 pandemic can provide insights into future strategies for mental health support and stress management, ensuring the continuity of nursing services during major health crises. However, we believe that enhancing nursing managers' awareness of compassion fatigue, PTSD, their interconnection, and their impact on work quality can aid in developing more targeted strategies and preventing the onset and progression of these symptoms. While nurses strive to safeguard their own well-being and that of their colleagues, collaboration among various stakeholders is essential to devise innovative and beneficial solutions. By working together, any risks associated with compassion fatigue and PTSD within the nursing workforce can be identified and mitigated effectively. Recommendations for future studies involve incorporating qualitative methodologies to delve into the nuanced challenges faced by nurses and capturing their firsthand experiences during epidemic outbreaks to enrich the research findings.

LIMITATIONS OF THE STUDY

One of the limitations of this research was the inability to assess the psychological and physiological well-being of nurses prior to caring for COVID-19 patients due to the sudden onset of the pandemic. Additionally, PTSD is linked to various psychiatric and physical comorbidities, including depression, panic disorders, and other mental health issues, as well as challenges in marital, family, and social relationships. The use of cross-sectional correla- tional studies may constrain the ability to establish causality, especially in understanding outcomes like PTSD effectively. The incorporation of a mixed-methods approach could offer deeper insights into the personal experiences of nurses, potentially enhancing the research outcomes.

Another limitation of our study was the failure to account for confounding factors related to anxiety and perceived social support. Our research primarily focused on demographic and occupational factors in Iran. Furthermore, adopting qualitative methods would enable a comprehensive exploration of the challenges faced by nurses and the documentation of their experiences during epidemics, thereby enhancing the overall study.

We add this issue of “not using a control group” as one of the limitations of the research and recommend other researchers to consider this issue in similar studies in the future.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

It is hereby acknowledged that all authors have accepted responsibility for the manuscript's content and consented to its submission. They have meticulously reviewed all results and unanimously approved the final version of the manuscript.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| PTSD | = Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder |

| QWL | = Quality of Work Life |

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

This article reports the results of a research project approved by Mashhad University of Medical Sciences with the code of ethics IR.MUMS.REC.1399.450.

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

All procedures performed in the study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee and with the 1975 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author [S.G] upon reasonable request.