All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Assessment of Prevalence, Knowledge of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome and Health-related Practices among Female Nurses in Lebanon

Abstract

Introduction

In women of reproductive age, polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) is a prevalent endocrine illness that has detrimental effects on metabolism, reproduction, the endocrine system, and psychological health. The quality of life for women with PCOS is significantly impacted by its symptoms related to excess androgen and atypical menstruation.

Objective

There is a scarcity of data on female nurses' knowledge concerning PCOS and health-related practices. This study aimed to determine the prevalence, knowledge, and practices of PCOS among female nurses in Lebanon. In addition, we assessed whether these nurses have menstrual irregularities, obesity, hirsutism, extreme acne problems, and whether they are aware of the syndrome or not.

Methods

Using a self-administered questionnaire in Arabic and English languages, a descriptive cross-sectional study was carried out among Lebanese female nurses. Demographic characteristics were reported using descriptive statistics. The differentiating, associating, and correlating characteristics of the variables were reported using inferential statistics.

Results

The vast majority of respondents (91.5%) had good knowledge, and (39.6%) had good health-related practices. Nearly half (47.2%) were suspected to develop PCOS, and 8.5% were diagnosed based on signs and symptoms. According to the study's findings, nurses were unaware of the condition even though many exhibit its symptoms. The study also reported that 31.1% of participants were overweight, and eight (7.5%) were obese.

Conclusion

Despite having knowledge of the PCOS risk factors, females had considerably less practice in related fields of health. Female nurses with suspected or confirmed PCOS should seek immediate medical help since early diagnosis or treatment for PCOS is useful in enhancing their quality of life.

1. INTRODUCTION

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is an endocrine condition that inhibits the functioning of the ovaries due to an imbalance of female sex hormones, leading to the formation of cysts inside the ovarian sac. A few studies have detailed the origin of the phrase 'polycystic ovary syndrome' [1-3]. The presence of particular clinical, biochemical, and ultrasonography results allows for the diagnosis of this heterogeneous disease, whereas symptoms determine how a syndrome is managed [3-5]. Women who have PCOS are more likely to experience infertility, endometrial cancer, and late menopause, as well as metabolic problems such as insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes, and dyslipidaemia [3, 6].

Our daily lives have been greatly altered by the impact of modernization and technological advancement. Sugar, fast food, and soft drinks are increasingly dominating our diets. This improper eating and lack of exercise contribute to PCOS [7]. Clinical manifestations of PCOS include oligo-/amenorrhea, infertility, and pregnancy loss, in addition to obesity, acanthosis nigricans, hirsutism, acne, and male pattern baldness [4].

Globally, the geographic variations of PCOS prevalence have been investigated in recent years. The prevalence of PCOS is commonly reported to range between 2% and 26% [6]. PCOS is estimated to affect around 5 million reproductive-aged females in the United States [8]. Public awareness of the disorder's symptoms is crucial in identifying women who require therapy. PCOS awareness is more than just recognizing an illness; it is also about understanding the benefits of women's quality of life and life expectancy. The health risks linked with PCOS may negatively affect the quality of life and deteriorate the health of women.

The disease's symptoms arise throughout adolescence [9], where, at this age, girls are unable to recognize the signs of the disease, and the diagnosis is delayed due to a lack of awareness and knowledge about Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Late diagnosis raises the risk of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease and may impair women's ability to get pregnant [10]. Patients need health education to fully understand their condition and manage their symptoms. Health education is critical in assisting patients in understanding their illnesses and managing their symptoms. A recent survey found that over 25.0% of gynaecologists and reproductive endocrinologists were unfamiliar with the diagnostic criteria for PCOS. This suggests that many clinicians may fail to recognize the benefits of lifestyle changes, as well as the associated challenges and comorbidities faced by patients with PCOS [11]. Furthermore, women diagnosed with PCOS expressed discontentment with the care and assistance provided by medical practitioners [12].

Nurses play a crucial role in healthcare, especially for adolescents with PCOS, making PCOS knowledge essential. Lebanon has limited statistics on nurses' awareness of the syndrome. Given the particular circumstances of the COVID-19 pandemic and Lebanon's economic crisis, which resulted in broad disruptions and uncertainty, including potential implications for healthcare professionals, the primary objective was to conduct an exploratory assessment of the prevalence, knowledge, and health-related practices concerning PCOS among female nurses in Lebanon. The study sought to collect data and insights without making definitive predictions, acknowledging that the country and its healthcare system's unprecedented challenges during this period may have influenced various aspects of nurses' lives and professional practices in unanticipated manners. Furthermore, assessing the prevalence of PCOS among female nurses in Lebanon contributes to raising awareness about PCOS, promoting early detection, and implementing appropriate interventions to improve health outcomes.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study Design, Sampling, and Sample Size

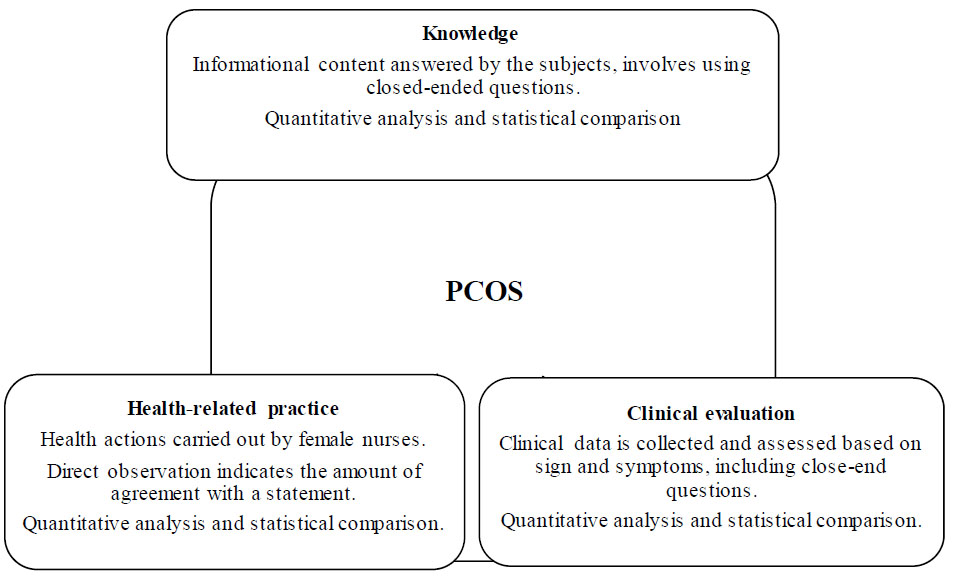

This descriptive cross-sectional survey among female nurses in Lebanon was conducted from June 2023 to September 2023. The sample size consisted of 106 female nurses. Inclusion criteria required respondents to be female nurses aged 17 to 45 who had not received a clinical diagnosis of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Exclusion criteria included individuals who refused to participate, did not fully complete the questionnaire, self-reported having PCOS, or were not part of the nursing field. Respondents were recruited through various social media platforms such as Facebook, WhatsApp, and Instagram. Data were collected using a pre-tested, self-administered, closed-ended, and structured questionnaire adapted from two prior studies [13, 14]. The questionnaire comprised four sections: the first documented respondents' characteristics and the second included 20 questions about PCOS knowledge and 1 question about the source of knowledge, the third contained 10 questions about health-related habits, and the fourth consisted of 12 clinical assessment questions about the prevalence of PCOS. Additionally, the questionnaire was translated into Arabic and included an English version of each question to ensure participants' understanding. Participants were informed about the study's objectives and assured of the confidentiality and privacy of their survey responses and personal information. They were assured that the information collected would be used for research purposes only. This study adhered to the STROBE guidelines for cross-sectional epidemiological studies in terms of design, setting, analysis, and reporting.

2.2. Questionnaire Validation

A group of professionals, including researchers, physicians, and academicians, assessed the questionnaire. They evaluated its content relevancy, clarity, simplicity, and ambiguity. The questionnaire was translated into Arabic and English. Participants were informed about the study's objectives and assured of the confidentiality and privacy of their survey responses and personal information. They were assured that the information gathered would be used for research purposes only. Cronbach's alpha coefficient was used to calculate internal consistency, resulting in a value of 0.762 for the knowledge section and 0.769 for the health-related practice section.

2.3. Scoring Criteria

Twenty questions related to knowledge were asked, and assessments were made using a mean cut-off point of 11. Respondents were considered as having poor knowledge or good knowledge depending on whether their knowledge score was less than 10 or more than 11, respectively. A total of 12 questions about the presence of PCOS symptoms and signs were asked in the clinical examination section. PCOS was not suspected in respondents with three or fewer symptoms but was in those with four to eight symptoms. However, if a response exhibits more than eight PCOS symptoms, a diagnosis of PCOS is considered [13]. In the last section, the questionnaire included ten questions about respondents' health-related practices. Each of these questions was rated using a 5-point Likert scale, indicating the amount of agreement with a statement. Depending on whether a respondent's practice score was less than or more than 30, the mean cut-off value of 31 was used to categorize them as having poor or good health practices.

2.4. Ethical Permission

The study was approved on May 5, 2023, by the LIU Institutional Review Board, with ethical authorization (LIUIRB-230503-SS-274). Informed consent was obtained from subjects participating in the research study, and privacy of information was guaranteed to them.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

The Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 26 and Microsoft Office Excel 2016 was used, respectively, for data collection and analysis. Categorical variable frequencies with percentages and continuous variable means were reported using descriptive statistical approaches. For inferential analysis, significant differences between variables were analysed using parametric tests such as cross-tabulation analysis.

3. RESULTS

This survey received 106 responses. Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics. The vast majority of respondents, 69 (65.1%), were between the ages of 22 and 26 years, with a mean age of 23.39 ± 0.811. Eighty respondents (75.5%) resided in urban areas. Most of the responders, 82 (77.4%), were single. Seventy-eight (73.6%) of the participants chose universities for their nursing studies, while 28 (26.4%) chose other institutions. The majority of them obtained Bachelor of Science (BS) degrees (62.3%), with only 11.3% holding master’s degrees in nursing. Furthermore, half of the nurses were employed (50.9%), with 91.1% of them working in hospitals.

| Description | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (Years) | - |

| 17-21 | 6(5.7%) |

| 22-26 | 69(65.1%) |

| 27-31 | 15(14.2%) |

| 32-36 | 16(15.1%) |

| BMI category | - |

| <18.5kg/m2 | 6(5.7%) |

| 18.5kg/m2 – 24.9kg/m2 | 59(55.7%) |

| 25.0kg/m2 – 29.9kg/m2 | 33(31.1%) |

| ≥30kg/m2 | 8(7.5%) |

| Marital status | - |

| Single | 82(77.4%) |

| Married | 21(19.8%) |

| Divorced | 3(2.8%) |

| Locality | - |

| Rural | 26(24.5%) |

| Urban | 80(75.5%) |

| Highest education degree | - |

| BP1 | 3(2.8%) |

| BP2 | 1(0.9%) |

| BP3 | 0(0%) |

| BT1 | 0(0%) |

| BT2 | 7(6.6%) |

| BT3 | 5(4.7%) |

| TS1 | 2(1.9%) |

| TS2 | 5(4.7%) |

| LT | 5(4.7%) |

| BS | 66(62.3%) |

| Master’s | 12(11.3%) |

| PhD | 0(0%) |

| University/Institution degree | - |

| Institution Degree | 28(26.4%) |

| University Degree | 78(73.6%) |

| Employment status | - |

| Employed | 54(50.9%) |

| Unemployed | 17(16%) |

| Self Employed | 3(2.8%) |

| Student | 30(28.3%) |

| Housewife | 2(1.9%) |

| Retired | 0(0%) |

| Designation/role | - |

| Staff nurse | 9(8.5%) |

| Nurse in charge | 16(15.1%) |

| Registered nurse | 48(45.3%) |

| Head of nursing | 3(2.8%) |

| Clinical nurse | 2(1.9%) |

| Others | 28(26.4%) |

| Do you work at the hospital | - |

| Yes | 45(42.5%) |

| No | 61(57.5%) |

| Mother education | - |

| Early childhood education | 5(4.7%) |

| Primary education | 33(31.1%) |

| Secondary education | 42(39.6%) |

| University graduate | 16(15.1%) |

| Postgraduate | 2(1.9%) |

| None | 8(7.5%) |

| Father education | - |

| Early childhood education | 6(5.7%) |

| Primary education | 37(34.9%) |

| Secondary education | 35(33%) |

| University graduate | 17(16%) |

| Postgraduate | 4(3.8%) |

| None | 7(6.6%) |

The mean ± SD of knowledge, clinical evaluation, and health-related practices scores in this study were 1.915 ± 0.2800, 1.641 ± 0.635, and 1.411 ± 0.494, respectively. In this study, 50 (47.2%) participants were suspected of having PCOS, while 47 (44.3%) did not have the condition. Of the respondents, 9 (8.5%) had PCOS based on signs and symptoms. Furthermore, nine (8.5%) of the respondents had weak knowledge, whereas 97 (91.5%) had strong knowledge. Sixty (56.6%) of the respondents had poor health-related habits, while 42 (39.6%) engaged in excellent health-related practices.

The questions shown in Table 2 evaluate the participant's basic knowledge. Based on the findings, it is clear that the participants have a good level of knowledge. A total of 100 respondents (94.3%) had heard about androgen hormone levels, and 76 (71.7%) knew that PCOS increased androgen levels. The presence of small multiple cysts in the ovaries of PCOS patients was known to 99 (93.4%) of them. Furthermore, 109 (98.1%) of those who responded were aware that irregular menstruation is a sign of PCOS. However, 12 of them (11.3%) were unaware that prediabetes can result in PCOS. Additionally, 18 (17%) answered that they were unaware that PCOS can lead to heart problems. 2.8% indicated that they were unaware that PCOS symptoms can be reduced by medications (like clomiphene and letrozole).

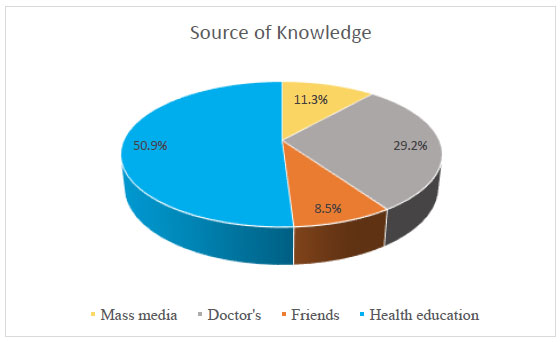

Regarding the source of knowledge, Fig. (1) shows how frequently each source of information was selected. According to the interpretation, health education (50.9%) was the most often selected source, followed by doctors (29.2%) and mass media (11.3%). Friends were the least preferred source of information, accounting for only 8.5% of the total.

| Description | N(%) |

|---|---|

| Have you heard about the term called “polycystic ovary syndrome” (PCOS)? |

- |

| Yes | 105(99.1%) |

| No | 0(0%) |

| I do not know | 1(0.9%) |

| Source of knowledge | - |

| Health education | 54(50.9%) |

| Doctor’s | 31(29.2%) |

| Mass media | 12(11.3%) |

| Friends | 9(8.5%) |

| Have you heard about androgen (male) hormone (e.g. testosterone and androstenedione)? |

- |

| Yes | 100(94.3%) |

| No | 6(5.7%) |

| I do not know | 0(0%) |

| In PCOS there is an increased level of androgen hormone? |

- |

| Yes | 76(71.7%) |

| No | 2(1.9%) |

| I do not know | 28(26.4%) |

| Patient suffering from PCOS have small multiple cysts in their ovaries. |

- |

| Yes | 99(93.4%) |

| No | 3(2.8%) |

| I do not know | 4(3.8%) |

| Obesity may cause PCOS. | - |

| Yes | 88(83%) |

| No | 6(5.7%) |

| I do not know | 12(11.3%) |

| Prediabetes condition (due to decreased insulin action in the body) may cause PCOS. |

- |

| Yes | 60(56.6%) |

| No | 12(11.3%) |

| I do not know | 34(32.1%) |

| Irregular or absence of menstrual (period) cycle is a symptom of PCOS. |

- |

| Yes | 104(98.1%) |

| No | 1(0.9%) |

| I do not know | 1(0.9%) |

| An unusual amount of hair growth on different body parts (upper lip, chin, abdomen, breast, thighs etc.) is a symptom of PCOS. |

- |

| Yes | 96(90.6%) |

| No | 3(2.8%) |

| I do not know | 7(6.6%) |

| Severe acne problems during the menstrual (periods) cycle are symptoms of PCOS. |

- |

| Yes | 74(69.8%) |

| No | 16(15.1%) |

| I do not know | 16(15.1%) |

| Hair loss from the scalp more than normal is a symptom of PCOS. |

- |

| Yes | 59(55.7%) |

| No | 13(12.3%) |

| I do not know | 34(32.1%) |

| PCOS diagnosis can be confirmed by vaginal ultrasound. | - |

| Yes | 76(71.7%) |

| No | 9(8.5%) |

| I do not know | 21(19.8%) |

| Specific blood tests can be used for the diagnosis of PCOS. | - |

| Yes | 47(44.3%) |

| No | 29(27.4%) |

| I do not know | 30(28.3%) |

| PCOS may lead to diabetes (sugar). | - |

| Yes | 39(36.8%) |

| No | 34(32.1%) |

| I do not know | 33(31.1%) |

| PCOS may lead to heart diseases. | - |

| Yes | 18(17%) |

| No | 37(34.9%) |

| I do not know | 51(48.1%) |

| PCOS may lead to infertility (inability to have children) or reduced fertility (reduced chance of getting pregnant) |

- |

| Yes | 96(90.6%) |

| No | 3(2.8) |

| I don’t know | 7(6.6%) |

| PCOS may lead to anxiety and depression. | - |

| Yes | 97(91.5%) |

| No | 0(0%) |

| I do not know | 9(8.5%) |

| Hormonal therapy (oral contraceptive, hormone intrauterine device etc.) may be used to treat PCOS. |

- |

| Yes | 89(84%) |

| No | 3(2.8%) |

| I do not know | 14(13.2%) |

| Anti-diabetic medications (metformin) may be used to treat diabetes. |

- |

| Yes | 67(63.2%) |

| No | 10(9.4%) |

| I do not know | 28(26.4%) |

| Missing | 1(0.9%) |

| Symptomatic treatment (clomiphene, letrozole, acne topical cream, spironolactone, etc...) may be given to relieve the symptoms of PCOS. |

- |

| Yes | 53(50%) |

| No | 18(17%) |

| I do not know | 35(33%) |

| Surgery may be used to remove the ovarian cyst. | - |

| Yes | 92(86.8%) |

| No | 7(6.6%) |

| I do not know | 7(6.6%) |

In Tables 3 and 4, a clinical evaluation of PCOS is provided. Out of 106 female nurses who responded to the study, 9 (8.5%) were diagnosed based on signs and symptoms, whereas 50 (47.2%) were suspected. According to the results, 56 (52.8%), 62 (58.5%), 49 (46.2%), 54 (50.9%), and 53 (50%) experienced extremely heavy periods, acne throughout the menstrual cycle, an unusual amount of hair loss from the scalp, excessive hair growth at different parts of the body, and a family history of diabetes, respectively. Twenty-four (22.6%) had dark colour patches on their skin and a family history of PCOS, while 38 (35.8%) had continuous abnormal weight and prolonged periods. Furthermore, 29 (27.4%) experienced a complete absence of periods, and 42 (39.6%) experienced partial absence of periods.

Responses related to health practices are depicted in Table 5. Forty-nine (46.2%) of the respondents sometimes included high-fiber foods in their diets, while 16 (15.1%) usually consumed high-fiber foods in their daily diets. Forty-eight (45.3%) claimed they sometimes read nutrition labels, 12 (11.3%) reported they usually do so, and 11 (10.4%) answered that they always read nutrition labels. Despite this, 14 (13.2%) of the respondents answered that they never read nutrition labels in their daily lives. Most respondents (38.7%) stated that they sometimes incorporate low-fat foods into their diets, and 9.4% always incorporated low-fat meals into their diets. Additionally, 25 (23.6%) of them rarely control their meals on weekends, and 34 (32.1%) never exercise for 30 minutes five days a week (Fig. 2).

| Description | N(%) |

|---|---|

| History of PCOS in your mother or sister? | - |

| Yes | 24(22.6%) |

| No | 77(72.6%) |

| I do not know | 4(3.8%) |

| Missing | 1(0.9%) |

| Very heavy periods (more than 2 pads per day)? | - |

| Yes | 56(52.8%) |

| No | 42(39.6%) |

| I do not know | 6(5.7%) |

| Missing | 2(1.9%) |

| Prolonged menses (more than 7 days)? | - |

| Yes | 38(35.8%) |

| No | 64(60.4%) |

| I do not know | 2(1.9%) |

| Missing | 2(1.9%) |

| Total absence of menses? | - |

| Yes | 29(27.4%) |

| No | 68(64.2%) |

| I do not know | 6(5.7%) |

| Missing | 3(2.8%) |

| Partial absence of menses (not after 28 days)? | - |

| Yes | 42(39.6%) |

| No | 53(50%) |

| I do not know | 9(8.5%) |

| Missing | 2(1.9%) |

| - | - |

| Acne problem during menstrual cycle? | - |

| Yes | 62(58.5%) |

| No | 36(34%) |

| I do not know | 5(4.7%) |

| Missing | 3(2.8%) |

| Does an unusual amount of hair growth occurs in different parts of your body (upper lip, chin, abdomen, breast, thighs, etc.)? |

- |

| Yes | 54(50.9%) |

| No | 45(42.5%) |

| I do not know | 5(4.7%) |

| Missing | 2(1.9%) |

| Unusual amount of hair loss from the scalp? | - |

| Yes | 49(46.2%) |

| No | 44(41.5%) |

| I do not know | 10(9.4%) |

| Missing | 3(2.8%) |

| Discoloration or dark color patches on skin. | - |

| Yes | 24(22.6%) |

| No | 68(64.2%) |

| I do not know | 11(10.4%) |

| Missing | 3(2.8%) |

| Continuous abnormal weight gain? | - |

| Yes | 38(35.8%) |

| No | 61(57.5%) |

| I do not know | 4(3.8%) |

| Missing | 3(2.8%) |

| Do you have diabetes? | - |

| Yes | 3(2.8%) |

| No | 100(94.3) |

| I do not know | 103(97.2%) |

| Missing | 3(2.8%) |

| Family history of diabetes? | - |

| Yes | 53(50%) |

| No | 49(46.2%) |

| I do not know | 1(0.9%) |

| Missing | 3(2.8%) |

| Clinical Evaluation | N(%) |

|---|---|

| Currently diagnosed | 9(8.5%) |

| Suspected | 50(47.2%) |

| Not diagnosed | 47(44.3%) |

| Description | N(%) |

|---|---|

| How often do you read nutrition labels? | - |

| Never | 14(13.2%) |

| Rarely | 19(17.9%) |

| Sometimes | 48(45.3%) |

| Usually | 12(11.3%) |

| Always | 11(10.4%) |

| Missing | 2(1.9%) |

| I incorporate low-fat foods into my diet. | - |

| Never | 12(11.3%) |

| Rarely | 21(19.8%) |

| Sometimes | 41(38.7%) |

| Usually | 20(18.9%) |

| Always | 10(9.4%) |

| Missing | 2(1.9%) |

| I incorporate low-salt foods into my diet. | - |

| Never | 21(19.8%) |

| Rarely | 22(20.8%) |

| Sometimes | 31(29.2%) |

| Usually | 20(18.9%) |

| Always | 10(9.4%) |

| Missing | 2(1.9%) |

| I eat 5 servings of fruits and vegetables per day. | - |

| Never | 19(17.9%) |

| Rarely | 33(31.1%) |

| Sometimes | 27(25.5%) |

| Usually | 16(15.1%) |

| Always | 9(8.5%) |

| Missing | 2(1.9%) |

| I decrease the amount of refined sugar in my diet. | - |

| Never | 14(13.2%) |

| Rarely | 23(21.7%) |

| Sometimes | 38(35.8%) |

| Usually | 18(17%) |

| Always | 11(10.4%) |

| Missing | 2(1.9%) |

| I eat more high-fiber foods. | - |

| Never | 7(6.6%) |

| Rarely | 14(13.2%) |

| Sometimes | 49(46.2%) |

| Usually | 18(17%) |

| Always | 16(15.1%) |

| Missing | 2(1.9%) |

| I eat smaller portions at dinner. | - |

| Never | 13(12.3%) |

| Rarely | 18(17%) |

| Sometimes | 30(28.3%) |

| Usually | 24(22.6%) |

| Always | 19(17.9%) |

| Missing | 2(1.9%) |

| I exercise 30 minutes 5 days a week. | - |

| Never | 34(32.1%) |

| Rarely | 21(19.8%) |

| Sometimes | 29(27.4%) |

| Usually | 9(8.5%) |

| Always | 10(9.4%) |

| Missing | 3(2.8%) |

| I control my eating on weekends. | - |

| Never | 29(27.4%) |

| Rarely | 25(23.6%) |

| Sometimes | 25(23.6%) |

| Usually | 19(17.9%) |

| Always | 5(4.7%) |

| Missing | 3(2.8%) |

| It is easy for me to eat a healthy diet. | - |

| Never | 17(16%) |

| Rarely | 19(17.9%) |

| Sometimes | 26(24.5%) |

| Usually | 25(23.6%) |

| Always | 17(16%) |

| Missing | 2(1.9%) |

4. DISCUSSION

In 2020, PCOS prevalence rates ranged from 2.2% to 48% in various countries [15, 16]. Our study found that the prevalence rate in Lebanon was 8.5%. Previous studies reported similar rates in South India (9.13%) [17], Omani women (7%) [18], and Bhopal, India (8.2%) [19]. However, no comparable previous prevalence study has been conducted on Lebanese nurses. Variations in prevalence were linked to different study populations [13] and the use of different diagnostic criteria, such as Rotterdam, National Institutes of Health Criteria (NIH), and Androgen Excess and PCOS (AE-PCOS) criteria [20].

Our clinical investigation regarding manifestations revealed that, based on signs and symptoms, 47.2% of patients were suspected of having PCOS. This indicates that many females do not consult gynecologists due to low wages in Lebanon. Even with health insurance, medical care avoidance still exists among nurses associated with the Orders of Nurses in Lebanon. According to two surveys conducted in Pakistan, 22% of adolescents consider discussing sexual organs or disorders with family members the most appropriate action, while the majority prefer obtaining medical advice [21]. Furthermore, the results of the second study showed that family members do not usually accompany women to hospitals unless there is an emergency, as taking a woman from her home to the hospital is considered disrespectful [22].

According to the current study, the majority of respondents were aware of PCOS and its signs and symptoms. This finding agrees with Sasikala et al. (2021), who investigated the knowledge and awareness of polycystic ovarian syndrome among nursing students in South India [23]. The current study's findings are also consistent with those of Al Bassam et al. (2018), who studied PCOS awareness among female students at Qassim University in Saudi Arabia [24]. However, the study's findings conflict with those of Salama et al. (2019), who examined PCOS knowledge among nursing students at Benha University in Egypt [25]. These discrepancies may be due to the smaller sample size and variations in communities and cultures, a lack of conversations about reproductive health in families, and difficult access to resources.

It was observed that the most common sources of information were educational health (50.9%) and doctors (29.2%). Similar studies, on the other hand, showed different findings in terms of the most common source of information. A cross-sectional study in UAE conducted among females revealed that the most common source of knowledge was friends and family [26].

Evidence from this study revealed that knowledge of PCOS was strongly influenced by age, education level, mother's education, and history of PCOS diagnosis. Age and knowledge score had a significant correlation in our study (Chi-square = 8.790, P-value = 0.032). Statistics revealed a strong correlation between educational level and knowledge score (Chi-square=19.280, P-value=0.013), as well as between mother's education and PCOS family history (Chi-square=10.185, P-value=0.070, Chi-square=2.879, P-value=0.090) respectively. Devi (2017) found a highly statistically significant association between student age and mother's education and the level of knowledge [27]. Additionally, these results were consistent with those of Sowmya and Anitha (2017), who conducted a clinical investigation of polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) in a tertiary care facility and demonstrated a relationship between ages and knowledge scores [28].

In comparison to the marital status of female students, female nurses were single in the vast majority of cases (77.4%). This outcome was consistent with the findings of El Sayed et al. (2020) in Egypt [29], Al Bassam et al. (2018) in Saudi Arabia [24], and Omagbemi et al. in Nigeria (2020) [30], who found that the majority of the participants were single.

The current study demonstrated that female nurses who attended universities had higher overall knowledge scores than those who attended nursing or health technical institutes. This outcome appears to be unexpected. Furthermore, after revising the literature review, we found no research addressing this subject. This variance may result from the varied curricula in universities and institutions as well as the difference in the sample size of female nurses who attend universities or institutions.

In terms of family residency, more than three-quarters of the nursing students were from urban regions, which corresponds with the results of Shrivastava et al. (2019) in India [31]. However, this finding contrasts with the findings of El Sayed et al. (2020), Memon et al. (2020), and Salama et al. (2019), who discovered that 61.1%, 64.3%, and 74.3% respectively were from rural areas [25, 29, 32].

Our findings suggest that respondents with a family history of PCOS are knowledgeable about the condition (100%). Once a family member is diagnosed with PCOS, they acquire knowledge and often transfer this knowledge to siblings. This result aligns with other studies reporting a higher level of PCOS knowledge in women after diagnosis than before [33].

Patients with PCOS are advised to follow a healthy diet and to exercise regularly to manage their condition. Lifestyle changes are considered the best treatment for PCOS. A balanced diet with appropriate food components can help prevent or control the disease. The Healthy Eating Index (HEI) is one of many techniques used to assess dietary patterns [34]. However, our study found that 16% of respondents find it difficult to follow a healthy diet, and only 4.7% control their eating during weekends. Additionally, 11.3% never incorporate low-fat food into their diet, which can contribute to obesity and the development of PCOS [11]. According to Sedighi et al. (2014), exercise may benefit women with PCOS by reducing insulin resistance and body fat, which serves as a hormonal storage site for estrogen and steroid hormones [35]. However, only 9.4% of respondents reported always exercising for 30 minutes five days a week.

Obesity is prevalent among women with PCOS, with estimates suggesting that 40-80% of them are overweight or obese [36]. In our study, 66.7% of responders diagnosed with PCOS, according to signs and symptoms, were overweight (BMI of 25 kg/m2–29.9 kg/m2), while 33.3% had a healthy weight (BMI 18.5 – 24.9 kg/m2).

Our study found no significant correlation between the health-related practices of female nurses and a family history of PCOS, nor between BMI and a family history of PCOS. Similarly, PCOS knowledge was not significantly associated with PCOS health-related practices. This suggests that women with PCOS may not have satisfactory health-related practices despite being educated about the condition, which is consistent with a study conducted in the United States [14]. These findings highlight the urgent need for educational programs targeting these vulnerable groups. It is worth mentioning that female nurses with varying levels of PCOS knowledge exhibited different health-related practices influenced by their attitudes toward PCOS. Those with a negative attitude may be less likely to adopt a healthy lifestyle to lower the risk of developing PCOS compared to those with a positive attitude.

Furthermore, our study underscores the importance of screening PCOS women for related endocrine disorders such as hypothyroidism and hyperprolactinemia, as recommended by previous research. While our study did not directly investigate the screening practices of female nurses in Lebanon, identifying common endocrine disorders associated with PCOS emphasizes the critical role of nurses in advocating for comprehensive screening strategies [37].

CONCLUSION

The results of the present study indicate that more than three-quarters of the female nurses had good knowledge, although more than half had poor health-related practices. The findings revealed an increasing prevalence of PCOS signs and symptoms, yet many nurses were unaware of PCOS despite its presence in many of them. Consequently, it is imperative to implement educational programs on PCOS symptoms and signs to raise awareness among females. Furthermore, it is advisable for females to consult a gynaecologist at least once a year to improve their health.

LIMITATIONS

Given that this study was limited to female nurses in Lebanon, a group that may directly experience PCOS, the findings and implications cannot necessarily be extrapolated to male nurses who do not contend with PCOS. Furthermore, a notable limitation of our study is the absence of exploration into the potential influence of parents' education on nurses' understanding of PCOS. Although the current research aimed to comprehensively evaluate various aspects of nurses' knowledge and practices related to PCOS, we did not specifically examine how the educational backgrounds of nurses' parents might contribute to their understanding of this condition.

AUTHORS' CONTRIBUTION

All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

ABBREVIATIONS

| SPSS | = Statistical Package for Social Services |

| BMI | = Body Mass Index |

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

The ethical committee of the Lebanese International University Institutional Review Board (IRB) reviewed and approved the study (Reference LIUIRB-230503-SS-274). Informed consent to participate was obtained from all the participants included in the study.

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of institutional and/or research committees and with the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki, as revised in 2013.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Informed consent was obtained from all participants of this study. The questionnaire included a consent form that highlighted the purpose of the study, guaranteed confidentiality and anonymity, and stated that participation by female nurses is voluntary.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

The data supporting the findings of our article can be found within the link provided, which was used to collect data: https://docs.google.com/forms/d/1UdOAW5wILp2aM ET_1lhfZXygWKl-Uv70elRm5rTFQUo/edit.