All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Efficacy of a Mental Health Game-Board Intervention for Adolescents in Remote Areas: Reducing Stigma and Encouraging Peer Engagement

Abstract

Background

A good understanding of health-related information is crucial for people to make informed decisions about their well-being. Mental health disorders like depression and anxiety can have a significant impact on one's quality of life. Unfortunately, not everyone has equal access to resources and health education, hindering their health literacy. Adolescents in remote areas with mental health issues have more difficulties in addressing their disorder due to the limited resources available, which can have long-term consequences. Peer support interventions have successfully promoted behavioral changes and addressed mental health problems. Digital and online game-based learning has widely been used in mental health education. Board games have several advantages over digital game-based learning in improving the effectiveness of game-based learning in mental health education among adolescents in remote areas.

Objective

This study examined the effectiveness of game-based learning using a board game called “Carpe Diem” in adolescent mental health intervention. Our focus was to assess the effect of board games on awareness, peer involvement, and stigma about adolescent mental health.

Methods

We used a mixed-methods approach with an embedded experimental model involving 45 senior high-school students chosen using cluster random sampling to represent the variety of school characteristics in Kupang City, Indonesia, in January 2020. Quantitative data were collected through a non-control group quasi-experimental design using pre- and post-tests with open-ended and post-exposure questionnaires. Qualitative data were collected through a focus group discussion and further analyzed using content analysis.

Results

The quantitative pre-post test results showed an increased average score with significant differences in stigma and awareness of mental health problems. The content analysis showed that the Carpe Diem board game could help decrease stigma, increase awareness of mental health problems, and encourage peer engagement in health-seeking behavior. However, we also discovered that the board game needed improvements in its integration with the formal curriculum and real-life situations.

Conclusion

Adding adjuvant interventions, such as game-based learning, to conventional psychoeducation strategies can improve awareness, decreasing stigma and positive peer involvement in health-seeking behaviors for adolescents' mental health in similar characteristics regions. Further improvement is still needed to improve the efficacy of the Carpe Diem.

1. INTRODUCTION

Health literacy has emerged as one of the most significant determinants of health. [1] Health literacy is the cognitive and social skills determining an individual's motivation and capacity to access, comprehend, and apply health-promoting and health-maintaining information. Health literacy deficiencies can increase the prevalence of many diseases, including mental health issues. [2] Inequity and unequal access to adequate resources and health education pose significant barriers to enhancing health literacy. [3] Several strategies must be adopted and adapted to improve the marginalized populations' health literacy, considering their sociocultural and socio- demographic circumstances. [4]

The magnitude of impairment caused by mental health disorders has grown faster [5, 6]. Depressive and anxiety disorders were the two major mental disorders etiology with the most significant impact on the disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) and years lived with disability (YLDs) of adolescents and nearly all age groups. [5] Mental health disorders among adolescents have gained increasing attention due to their prevalence and potential long-term consequences [7]. Half of all mental health conditions begin by age 14, and most cases go undetected and untreated [8].

The situation is exacerbated in remote, periphery, or marginalized areas with limited resources and access to mental health services. Addressing mental health disorders among adolescents in this area becomes crucial due to their high prevalence and potential long-term consequences. The unique challenges adolescents face in such regions must be recognized and addressed through tailored interventions catering to their needs [9, 10].

The stigma surrounding mental health substantially hinders individuals seeking help and support [11]. Adolescents in peripheral areas often encounter even more significant challenges as they encounter social stigma and discrimination. Limited awareness and understanding of mental health issues contribute to this stigmatization [12]. As a result, individuals may internalize this stigma, leading to self-stigmatization, which hinders their willingness to seek professional help and impedes their path to recovery.

Peers play a significant role in adolescents ' lives and influence their behaviors, attitudes, and overall mental well-being. Peer support interventions have shown promising results in various contexts. Leveraging the power of peer relationships can profoundly impact adolescent mental health outcomes [13]. Through peer support, adolescents gain access to a network of individuals who can empathize with their struggles and provide valuable support throughout their mental health journey [14].

Game-based learning can be defined as educational games, a subset of serious games, in which a fully-fledged game is developed to deliver immersive and attractive learning experiences that give particular learning goals, experiences, and results [15–18]. Game-based learning offers challenges that match the player's ability, creating flow and engagement that motivates participants to make behavioral changes. It provides a space for independent decision-making, reflects real-life autonomy, and attenuates the effectiveness of the traditional health education method [19, 20].

Games also offer a safe environment for experi- mentation and learning from failure [16, 21]. These motivational aspects of games contribute to their effectiveness in promoting behavioral changes and can be valuable in addressing various health issues, including mental health [12, 22, 23]. Several studies revealed the effectiveness of using computers and online games in mental health education and intervention. One main issue arose: the game's engagement and specificity to meet the targeted users' needs. A board game tends to have higher engagement benefits and more flexibility to adapt to users' needs [24, 25].

The primary objective of this study is to evaluate the effectiveness of a board game developed explicitly for adolescents' mental health education called “carpe diem” in stigma reduction, awareness improvement, and the role of peer involvement in managing adolescent mental health disorders. By assessing the impact of the intervention on these various outcomes, this research aims to contribute valuable insights into the potential of game-based learning approaches as a practical tool in addressing mental health literacy issues among adolescents in peripheral or remote marginated areas.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study employed a mixed-methods approach with an embedded experimental model. The research design consisted of a quantitative phase using a non-control group pre-post-test quasi-experimental design and a qualitative phase to explore the usefulness, strengths, weaknesses, and areas for improvement of the “carpe diem” board game intervention. In the quantitative phase, a minimum sample of 45 students chosen by cluster random sampling from four different characteristics of senior high schools in Kupang, East Nusa Tenggara province, Indonesia, participated in the study. The inclusion criteria are adolescent age (10-18 years), active senior high school students, and Kupang native citizens. Informed consent agreements were obtained from the parents and school counselor teacher. The study was conducted in January 2020. All participants were exposed to the “Carpe Diem” game-based learning intervention. A possible bias arose from the design: the age range of adolescents that did not involve adolescents aged 10-14 due to sampling sites in senior high school students.

“Carpe Diem” is taken from a phrase put forward by Horace ( Quintus Horatius Flaccus ): “ longer carpe diem, quam minimum credula poste r,” which is a form of motivation or invitation always to do your best every day. Carpe Diem is a cooperative game for 4 to 8 groups of players (each group can contain 1-3 people, so Carpe Diem can be played by up to 24 people) where each player must work together to face their various challenges. In Carpe Diem, each group of players plays the role of an individual who must equip themselves with a healthy mental condition to be able to spend the day productively and avoid depression. At the same time, each player must also help other colleagues to have a good mental condition. Every day, there will be a challenge where a player experiences heavy mental pressure due to an event. These events are representative of the various causes of depression in adolescents. If there is one or several players who fail to equip themselves with adequate mental conditions, they have the potential to experience depression. Because the concept is a cooperative game, each player will win if they consistently maintain their mental condition to complete each challenge. Each player will lose if they cannot fulfill this.

To assess the effectiveness of the intervention, a pre-validated mental health stigma and perception questionnaire using a five-scale Likert score, collabora- tively developed by the research team, psychologist, and psychiatrist, was administered to participants. This questionnaire measures changes in stigma, awareness, perception, and knowledge regarding mental health before and after intervention. It provided quantitative data to evaluate the impact of the board-game intervention on these outcomes by measuring the total score from each variable measured. Additionally, another questionnaire was utilized to determine the impact of the game-board experience on health-seeking behavior toward mental health problems.

Quantitative data obtained from the student questionnaires before and after the exposure to the intervention were analyzed using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. The statistical test compares the average total scores of the variables before and after the intervention to determine if there are statistically significant changes. The hypothesis was accepted if the resulting p-value was less than 0.05, indicating statistically significant changes in the measured variables. The qualitative phase aimed to gather insights and perspectives on the “carpe diem” board game. Focus group discussions (FGDs) were conducted with the participating students to collect data. An open-ended questionnaire was used to allow students to provide more detailed responses. The qualitative data collected through FGDs and questionnaires were analyzed using content analysis, a systematic method for examining and interpreting qualitative data. To assist with qualitative data analysis, the researchers employed the atlas.Ti ver.23 software. This software supports qualitative data analysis by providing tools for organizing, coding, and analyzing textual data. It helps identify the qualitative data's themes, patterns, and relationships. It facilitates a deeper understanding of participant's perspectives and experiences.

By integrating quantitative and qualitative approaches, this research aimed to understand the effectiveness of the “carpe diem” board game intervention in reducing mental health stigma and improving mental health awareness and perception of peer involvement in dealing with mental health problems among adolescents. Integrating both approaches provided a more holistic understanding of the intervention's impact and insights for future improvements.

3. RESULTS

Forty-five senior high school students who met the inclusion criteria and obtained informed consent from their parents or counselor teacher participated voluntarily in this research. The characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 1.

Table 2. shows variables from pre- and post-exposure to the board game, with higher scores representing a better perception of the subject. Stigma and fear towards mental illness and beliefs and perspectives on the existence and environmental cause of mental disorders show significant results with p < 0,05. However, there are no significant differences from other variables (Fig. 1).

| Gender | Male | 20 |

| Female | 25 | |

| Age | Min | 15 |

| Max | 18 | |

| Mean | 15,9 |

| Variable | Intake | Mean | Min | Max | SD | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stigma and fear towards mental illness and individuals with mental disorders | Pre | 11,7 | 3 | 19 | 3,4 | 0,00398* |

| Post | 9,8 | 4 | 18 | 3,0 | ||

| Beliefs and perspectives on the existence and environmental cause of mental disorders | Pre | 6,1 | 0 | 12 | 2,8 | 0,00578* |

| Post | 7,7 | 0 | 14 | 3,2 | ||

| Perceptions of Recovery and Treatment for Mental Disorders | Pre | 12,5 | 0 | 16 | 2,6 | 0,34212 |

| Post | 13,0 | 5 | 16 | 2,4 | ||

| Attitudes and beliefs toward interacting with individuals with mental disorders | Pre | 7,1 | 2 | 12 | 2,1 | 0,23014 |

| Post | 7,6 | 3 | 11 | 1,9 | ||

| Non-environmental causal factors and perceived dangers of mental disorders | Pre | 4,9 | 0 | 9 | 1,8 | 0,93624 |

| Post | 4,8 | 1 | 9 | 1,8 | ||

| Uncertainty surrounding the behavior of individuals with mental disorders | Pre | 23,6 | 16 | 34 | 4,3 | 0,88076 |

| Post | 23,7 | 11 | 37 | 5,2 |

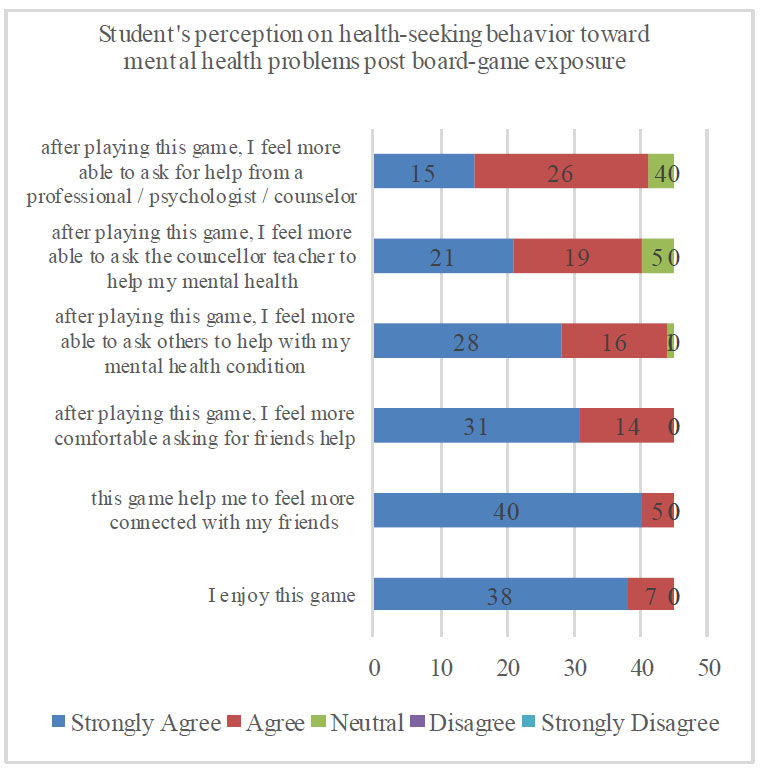

Student's perception of health-seeking behavior toward mental health problems after board-game exposure.

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. Stigma Reduction and “peer” Health-seeking Behavior

Analysis from the pre and post-test results of the stigma, perception, knowledge, and attitude toward the board game exposure questionnaire in Table 1. showed that only two variables showed significant differences, with all scores increasing. The first variable that exhibited a notable difference was related to the stigma and fear surrounding mental illness and those who suffer from mental disorders.

The findings in Table 1. were congruent with the Student's perception after exposure to the board game (Table 2). The perception of taking Professional and counselor help in mental health problems are the two components with the lowest proportion of strongly agree and agree answers. On the other hand, the perception of seeking peer help and engagement with peers had a higher proportion of strongly agree and agree on answers rather than the professional and counselor help in addressing mental health issues. These findings stated the advantage of the carpe diem board game in enhancing peer roles in adolescent mental health problems. Using board games, which facilitate simultaneous face-to-face interaction, could bring more engagement and emotional involvement between subjects.

| Theme | Sub-theme |

|---|---|

| Decreasing stigma | Better understanding of mental health problems. |

| Willingness to share a positive experience | |

| Increase awareness of the need for support. | |

| Increase awareness of mental health. | Know more about the solution to a problem. |

| Increase social sensitivity and awareness. | |

| Increase knowledge in mental health. | |

| Increase awareness of mental health. | |

| Targeted player Characteristic | Peer helper characteristics |

| Adolescents with mental health problems | |

| Effect of the game on the player's mental health conditions | Bring good change in life after playing the game |

| Adding a lot of lessons learned in life | |

| Better mental health condition | |

| Peer | Foster a cooperative nature and teamwork. |

| Realize the importance of social support. | |

| Teach a problem-solving skill. | |

| Stimulate supportive behaviour | |

| Foster a desire to help each other. | |

| Need for improvement of the game. | Need for integration with the formal curriculum. |

| Need for adjustment to meet life situation. | |

| The repeated visual motivational effect of the game | |

| Engagement of the player to the spirit of the game |

Social stigma was the fourth-highest-ranked barrier to help-seeking behavior in mental health problems [26]. Adolescents who face such stigma related to mental health issues may face negative consequences, including a reduced likelihood of seeking help and a lower quality of life. Various factors, including gender, can impact how adolescents perceive such stigma, as mentioned by the participant below:

“……… several factors influence depression itself, and it could be from family, society, the school environment, maybe like bullying; maybe it's also because he has his friends who he thinks can help him, but in reality, the sharing just makes his problems increase.” (M-17)

Findings from the content analysis in Table 3 showed that The Carpe Diem tends to reduce the stigma through a collaborative experience in facing many scenarios provided during the gameplay. Stigma and fear towards mental illness and individuals with mental disorders significantly differ in pre and post-test scores. These findings showed the possibility of the game-board intervention in reducing stigma. Stigma often consists of three components: stereotypes, which refer to negative preconceived notions about a specific individual or group; prejudice, which entails the presence of negative emotional responses; and discrimination, or the actions taken in response to it. Stigmas' primary consequence is deterring persons from pursuing treatment for mental health concerns [27, 28].

According to the previous research, gamification has been identified as a potential strategy for minimizing obstacles to participant engagement in interventions. It includes addressing participants' defensiveness and alleviating their suffering with destigmatizing as the outcome [29]. This board game also allows direct social contact with people with mental illness at the individual level at a similar time, and this direct interaction could decrease the stigma among players. This mechanism could explain why the stigma decreased in this study after the game-board exposure [30].

I learned that everyone is at risk of mental illness, and the causes and ways to deal with it are also different. When we run out of + cards, we will think that help from other people is also very important (F-17)

One contributing factor to stigma is the level of Mental Health Literacy (MHL) among individuals, which encompasses identifying mental health illnesses and knowing the appropriate avenues for seeking treatment [27]. Many children and adolescents experience mental health challenges that can impede their growth and overall well-being. Regrettably, most young people with mental illness do not actively seek or receive appropriate mental health services, a reluctance that can be attributed to the social stigma surrounding mental health issues [31].

From the health-seeking behavior post-exposure questionnaire results and the theme that emerged from the qualitative data (Table 3), most participants have a good mental health perception of seeking help with the most outstanding readiness: the willingness for friends or peer help. The health-seeking behavior findings are congruent with the pre-post test score Beliefs and perspectives on the existence and environmental cause of mental disorders, which significantly increase after the game-board exposure. Thus, a board game was reported to prevent illness-prone behaviors in young people effectively [32]. These points were mentioned by several participants, as represented in the quotes below:

Yes, this game made me think that no matter how great and capable I am, it turns out I still need other people to ask for help (M-17)

Because if there is stress and problems at home, they will come to share, share, and sometimes cry together. (F-16)

Using gamification techniques in board games can improve players' cognitive knowledge and generate a transformative shift in their attitudes and perspectives on a specific subject [32, 33]. Increased literacy increased awareness of this situation, resulting in a paradigm shift toward health-seeking behavior. Among other 'outside' people, peers or friends were the most preferred to be consulted in adolescent mental health difficulties. The involvement of peers with varying mental health statuses in board-game engagement could explain how peer preference outperformed other health-seeking activity preferences. Multiple studies demonstrating the benefit of peer support in reducing anxiety, decreasing effects, and increasing self-esteem in young people with mental illnesses could explain this conclusion [34].

The personality and characteristics of the peers involved can significantly impact the effectiveness of using the board game as a medium for peer support among adolescents with mental health issues. The qualitative analysis (Table 3) revealed that peer involvement could foster a cooperative nature and teamwork, help people realize the importance of social support, teach problem-solving skills, and stimulate supportive behavior. The board game can help them identify and start interactions with peers who experience similar problems. This peer interaction could also foster the experience of behavioral modeling and social learning in many studies [24, 35, 36].

4.2. Further Improvement of the “Carpe Diem”

A few adjustments need to be made to enhance the effectiveness of the game Carpe Diem and ensure that it fulfills its intended purposes. From the quantitative phase result of the pre-post test result in Table 1, the Carpe Diem board game tends to stimulate the change in subject perception toward stigma and general mental health awareness. Still, it needs improvement in mimicry role-playing the actual mental health problems in the local context. It includes perception regarding the risk factors, treatment or health-seeking behavior, how to deal with mental illness people, and the prognosis of the mental disorders.

Three significant improvements can be implemented based on the qualitative findings, as defined in Table 3. Firstly, integrating the game into the formal curriculum would provide a structured and educational context. Secondly, modifying the game rules to align with real-life situations would enhance its authenticity and practicality. The game development should capture the specific local context environmental determinants, including family dynamics, socioeconomic status, peer relationships, and exposure to adverse life events. Dysfunctional family environments, financial stressors, peer pressure, social relationships, and traumatic experiences have been demonstrated to contribute to the emergence of mental health challenges significantly [37, 38]. The board game has to fulfill the socio-dynamic and local context of mental health problem determinants, as mentioned by our participants below:

So, my parents had separated, and then when my mother remarried, it was like, Mom, you don't love me anymore; why did you have to remarry? But as time went on, I couldn't accept the depression, so what was the point of crying all the time? In the end, yeah, leave it alone (F-17)

For example, at home, our parents are angry, we think that our parents hate us, so we keep it in our minds and our hearts, that makes us have more and more burdens on ourselves, then outside our friends are like bullies, well that's basically where we keep the problems, so in the end they want more, he wants more, wants to be alone, quickly gives up, doesn't want to hang out with people that's what I know about the characteristics of depressed people (F-16)

Psychological factors, such as self-esteem, coping strategies, and emotional regulation skills, also play a pivotal role. Adolescents with inadequate coping mechanisms and difficulties in expressing and managing emotions are more susceptible to developing mental health disorders [39]. In conclusion, the intricate interplay of biological, environmental, and psychological factors collectively shapes the landscape of adolescent mental health problems. A comprehensive understanding of these determinants is imperative for formulating targeted interventions and preventative strategies using the board game Carpe Diem.

Thirdly, increasing the game's motivational impact could be achieved through repeated visual exposure to motivational stimuli, such as written quotes on the back of the cards that players need to emphasize verbally. Lastly, improving player engagement with the game's underlying message would be beneficial rather than solely focusing on winning. These last two enhancements are crucial since they are directly linked to the board game's objective [40].

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

The current research possessed some notable strengths. To the best of our understanding, this board game is a pioneering effort in the mental health field, and it is being used as a game-based education strategy, as it has been specifically designed to cater to the unique societal diversity found in Indonesia. Moreover, it possesses the potential for adaptation to other regions or countries with their distinct sociocultural contexts. In this study, we specifically focused on examining the potential benefits and areas for enhancement of a board game. Our investigation involved 45 adolescent participants residing in remote/periphery regions of the east part of Indonesia in a participatory design approach. This study makes a valuable contribution to the existing literature by examining the efficacy of incorporating games in mental health literacy, specifically the use of a board game, into the formal curriculum of secondary-level schools. The findings suggest that this approach can effectively enhance destigmatization by increasing awareness and encouraging adolescents with mental health problems to seek and or become peer helpers. Furthermore, the study highlights the potential of non-traditional psychoeducation methods, such as board games, in addressing mental health concerns within the formal school setting. These findings hold promise for the long-term sustainability of adolescent mental health interventions.

There were some limitations in this study. The sample of this study in the quantitative phase used the cluster of senior high schools and did not represent the whole age range of the adolescent population; therefore, during the qualitative phase, we used maximum variation sampling to select a sample that reflects the socioeconomic characteristics of adolescents in remote/periphery areas. Another strength of the study was the use of mixed methods, which contributed to an in-depth comprehension of how the proposed game was evaluated from a broader and more profound perspective in assessing and improving the board game for mental health in adolescents. Further studies that include junior high school adolescents and non-formal high school students will enhance the findings and insight regarding the variables of this study in the future.

CONCLUSION

The present study aimed to assess the efficacy of the board game “Carpe Diem.” It is an intervention in addressing mental health concerns among adolescents residing in a remote or peripheral region of Indonesia. This study posits that the mental health board games intervention has the potential to effectively address the specific needs and barriers to health-seeking behavior among adolescents in peripheral areas. It highlights the possibility of cooperative games in combating stigma, increasing awareness, and acknowledging the influence of peers in the management of adolescent mental health problems.However, further improvements are still needed to improve the efficacy of the Carpe Diem, especially in three areas: formal integration in the curriculum, adjustment of the reality mimicry of the game scenario, and the need for improving the motivational effects to the player.

The findings of this study have the potential to strengthen non-traditional tactics for promoting mental health and reducing stigma, improve health-seeking behavior, and eventually boost the overall well-being of adolescents in similar geographical areas. The board game intervention shows promise in fostering a supportive and inclusive atmosphere for adolescents to seek treatment and support for mental health illnesses voluntarily, which is achieved by reducing stigma, increasing awareness, and empowering peers to actively participate in managing these disorders. This study has provided significant findings on adolescents' mental health adjuvant intervention and laid the groundwork for subsequent interventions and initiatives in comparable settings.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

It is hereby acknowledged that all authors have accepted responsibility for the manuscript's content and consented to its submission. They have meticulously reviewed all results and unanimously approved the final version of the manuscript.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| MHL | = Mental Health Literacy |

| FGDs | = Focus Group Discussions |

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

Ethical approvals were obtained from Universitas Islam Bandung Health Research Ethics Committee Approval number 378/Komite Etik.FK/I/2019.

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of institutional and/or research committees and with the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki, as revised in 2013.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Informed consent agreements were obtained from the parents and school counselor teacher.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

The data and supportive information are available within the article.