All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Emotional Intelligence of Primary Health Care Nurses: A Longitudinal Randomized Clinical Trial

Abstract

Objective

This study recorded, investigated, and evaluated the emotional intelligence of primary health care nurses by means of an educational intervention in Greece.

Methods

This randomized clinical trial was conducted using a longitudinal experimental design. After obtaining written informed consent from each participant, the total study sample consisted of 101 higher education nurses working in primary health care in Greece. Two groups were created: the control group (51 participants) and the intervention group (50 participants). Both groups initially completed the questionnaire (pre-test). This was immediately followed by an educational intervention where only the intervention group participated, while there was no educational intervention in the control group. Finally, all participants, regardless of group, completed again the same questionnaire (post-test). The data were analyzed using a Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, Pearson's x2 test, Fisher's exact test, Student's t-test, non-parametric Mann-Whitney test, and the repeated measurement ANOVA.

Results

The study results indicated that the educational intervention had a positive effect on the intervention group, as the levels of emotional intelligence showed significant changes between the first and second measurements. Specifically, in the intervention group, in the “self-emotion appraisal” dimension, there was an increase in emotional scores by 0.38 (p-value 0.001) between the two measurements. In the “emotion appraisal of others” dimension, there was an increase of 0.27 (p-value 0.011); for the dimension “use of emotion”, it was 0.26 (p-value 0.05), and for the dimension “regulation of emotion”, it was 0.37 (p-value 0.008).

Conclusion

The interventions aiming at developing emotional intelligence have a positive impact, as they improve nurses’ emotional skills. Emotional intelligence courses may be included in the nursing department curriculum, as well as in similar programs for nursing staff.

1. INTRODUCTION

Recently, the importance of Emotional Intelligence (EI) in the health field has been increasingly emphasized with relevant references in nursing literature [1-4]. EI refers to a person's ability to recognize both their own emotions and those of others, successfully control them, and encourage self-motivation [5]. EI is considered of particular interest and value to nurses, given that a large part of their work is of an emotional nature [6-8].

Several researchers have been engaged in investigating the relationship between work and emotions. In particular, the studies focused on the increased workload, the management of emotions in the work context, and finally, the effect that emotions have on the health of health professionals [9-11]. Due to the special working conditions, the use and development of emotional skills is deemed necessary. This can help employees do their jobs better while safeguarding them against stressful situations [12, 13].

Emotions influence the professional relationships of healthcare professionals, both intrapersonally and interpersonally, as well as the decisions regarding patients’ health. In the healthcare sector, it has been observed that comprehending diverse emotions and their impact on the organizational context of work and leadership poses a challenge [13].

According to Freshwater and Stickley [14], for the best possible delivery of health care, nurses are required to interact with patients, physicians, and other specialties of health professionals consistently. The interaction between nurses and patients is of particular importance to nursing practice. This relationship is described as a complex process that involves nurses' perception, comprehension, and application of the emotions that the patients experience in order to effectively manage those emotions.

Health professionals should ideally exhibit experiential skills in regard to empathy as an EI dimension. This skill is the ability to approach patients' inner lives and learn as much as possible while acknowledging the patients’ problems. Communication skills are then used by health professionals in order to achieve the necessary control, clarification, support, understanding, reconstruction, and reflection on patients' ideas, perceptions, and emotions. Finally, the capacity to establish a mutually trusting long-term relationship with a patient serves as a motivator for healthcare professionals to emotionally connect with their patients. These long-term relationships are important to therapeutic outcomes, as they can contribute to listening and telling patients' stories.

EI is not innate in people, but it can be learned. Emotional behavior can be learned and developed when appropriate learning experiences are provided. That is, it can be developed through emotional learning programs [15].

Programs designed to enhance EI are based on EI models and theories of social and emotional development. Their aim is to develop emotions and social skills in issues related to mental health in order to improve the regulation of emotions, interpersonal relationships, self-esteem, and communication [16]. Engaging in a certain set of social behaviors, like recognizing and addressing emotions or communicating with others in a way that demonstrates “empathy”, can help in developing social skills [17]. According to Nelis et al. [18], the goal of EI training is to enhance the mood of trainees.

For EI intervention programs to be more successful, Triliva and Giovanni [17] outline four stages. During the planning stage, the needs, motivation, and level of readiness of the team are evaluated. During the implementation stage, the program is put into practice, with a focus on goal-setting, cultivating strong relationships between the group and the coordinator, practicing, and receiving feedback. The application of newly gained information and capabilities to settings outside the group is taken into consideration during the acquisition stage. Finally, in the evaluation stage, the program is evaluated both on an individual and a group level.

1.1. Purpose

The aim of this study was to record, investigate, and evaluate the EI of primary health care (PHC) nurses before and after an educational intervention or without an educational intervention.

2. METHODS

2.1. Research Design and Participants

A sample of two points in time was used for a longitudinal experimental design. After obtaining written informed consent from each participant, a questionnaire was implemented, and nurses employed in Greek PHC facilities received an educational intervention. Regarding the research sample, two groups were created: the control group and the intervention group. The nurses in the intervention group initially completed the questionnaire (pre-test), then immediately after the educational intervention, within one week, they completed the questionnaire again (post-test). In contrast to the intervention group, the nurses who made up the control group completed the questionnaire in the first phase. There was no educational intervention, and immediately afterward, in the second phase, the questionnaire was completed again within one month.

Data was collected by convenience sampling, which involved PHC nurses from a wide variety of geographical areas in Greece. Participants were randomly assigned to either the control or the experimental group with a 1:1 allocation using a computerized random number generator by the researcher. The study was single-blind because only the researcher knew which intervention each participant was receiving.

The survey was conducted from May, 2022, to December, 2022. The study sample consisted of 101 higher education nurses, the heads of the nursing departments, and subordinate nursing staff from various types of PHC facilities, such as Health Centers, Local Health Groups, Mental Health Centers, etc. The intervention group included a sample of 50 people, while the control group sample was 51 people. According to the power analysis, for this particular survey design, it was estimated that the total number of participants should be at least 100 (50 per group), which provides 90% power with an effect size equal to 0.30 for the between-group comparison, 95% power with an effect size equal to 0.18 for the comparison between two-time points, and 95% power with an effect size equal to 0.18 to control for the interaction term.

Only the nurses in the intervention group participated in the educational interventions. These interventions were conducted in PHC facilities, and their themes, which were implemented utilizing recommendations, were awareness, significance, value, advantages, and concerns associated with EI. Case studies were discussed at the conclusion of the lecture, providing an opportunity for debate and introspection. The intervention lasted approximately one hour. Unfortunately, due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the associated restrictions in place at the time, it was not possible to conduct a systematic and comprehensive intervention aiming at EI development.

2.2. Sample Selection

2.2.1. Inclusion Criteria

The inclusion criteria were:

The nurses:

- Speak the Greek language,

- Have a tertiary education in nursing,

- Consent to their participation in this research,

- Work in PHC institutions.

2.2.2. Exclusion Criteria

The exclusion criteria were:

- Other paramedical staff or supervisors, who practice nursing work without holding a nursing diploma or degree (e.g., midwives),

- Nursing assistants who have had two years of nursing training,

- Individuals working in secondary and tertiary health institutions,

- People who do not consent to their participation in this research.

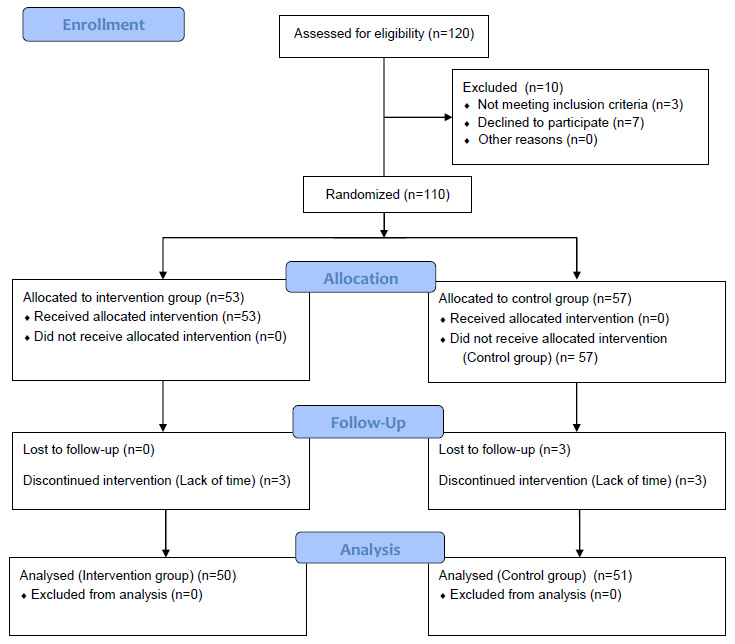

The CONSORT flowchart illustrates the progression of study participants through the phases of the randomized trial, from assessment of eligibility to analysis. Exclusions, allocations to intervention/control groups, follow-up, and final analysis numbers are detailed in the chart below (Fig. 1):

2.3. Questionnaire and Research Tools

The research was conducted using a questionnaire. The first part of the questionnaire asks for the filling in of demographic, social, and employment characteristics, as well as questions related to job satisfaction. The second part includes the Wong and Law Emotional Intelligence Scale.

2.4. Wong and Law Emotional Intelligence Scale (WLEIS)

It is considered one of the most reliable self-report psychometric research tools for assessing EI, as it is arguably one of the most widely used research tools worldwide. The scale is based on four dimensions according to the theory of Davies et al. [19] based on the model of Mayer and Salovey [20]. This scale examines both our own emotions and those of others, as well as the ability to manage and regulate them. The WLEIS has been translated and validated into the Greek language by Professor Kafetsios Konstantinos [21]. For the purposes of our research, permission has been requested and granted.

2.5. Research Ethics

Regarding our research study, upon request, the conduct of the research was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the University of West Attica (No. Prot: 12758 16/02/2022) and the scientific councils of all health districts of Greece. Furthermore, the study was registered in the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials, with registration reference: IRCT 20240126060816N1. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before their involvement in the study. The confidentiality and anonymity of participant data were rigorously observed throughout all stages of the research process, ensuring compliance with ethical standards and safeguarding the privacy and rights of the participants.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, the distributions of the quantitative variables were tested for normality. Those that were normally distributed were described using mean values and standard deviations (SD), while for those that were not normally distributed, medians and interquartile ranges were additionally used. Absolute (N) and relative (%) frequencies were used to describe qualitative variables. To compare proportions, Pearson's x2 test or Fisher's exact test was used where necessary. Student's t-test was used to compare quantitative variables between the two groups. The non-parametric Mann-Whitney test was used to compare ordinal variables between the two groups. Repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to test for differences in measurements between groups and over time. The assumptions of normality and sphericity of the model were checked and were not violated.

The CONSORT 2010 flowchart.

Moreover, with the above method, it was assessed whether the degree of change over time of the scales under study was different between the groups and whether it also depended on their demographic and employment data. To test the relationship between two quantitative variables, Pearson's correlation coefficient (r) was used. Significance levels were two-sided, and statistical significance was set at 0.05. The statistical program SPSS 26.0 was used for the analysis.

3. RESULTS

One hundred and one participants were entered in the study (50 in the intervention group and 51 in the control group). Their characteristics are presented in Table 1 by group. No significant differences were found between the two groups as far as their characteristics are concerned.

A significant difference was only noted in terms of good working conditions (logistical equipment), where participants in the control group were significantly more satisfied compared to participants in the intervention group (Table 2).

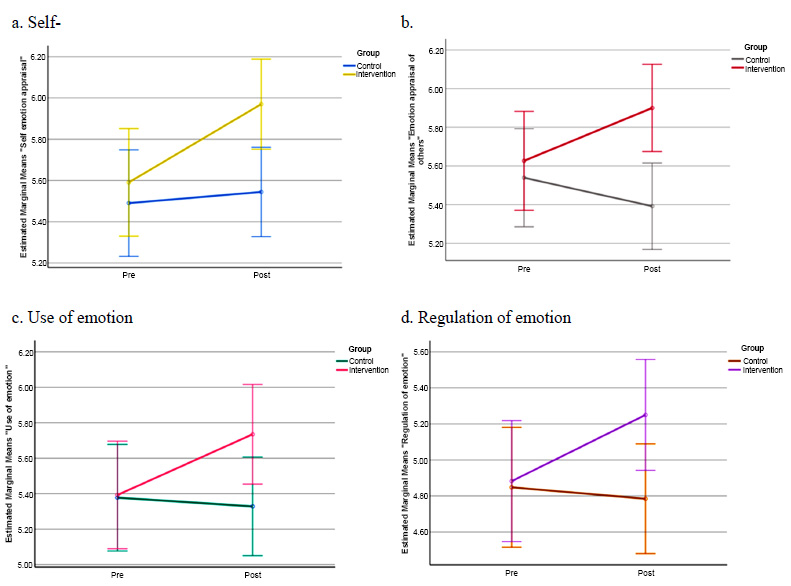

At baseline, emotional intelligence was similar in both groups. At follow-up, emotional intelligence was significantly greater in the intervention group regarding all subscales. The degree of change of all EI scores differed significantly between the two groups since significant increases were detected only in the intervention group (Table 3 and Fig. 2ad). The effect sizes of the change for the intervention group were 0.13 for self-emotion appraisal, 0.10 for emotional appraisal of others, 0.07 for the use of emotion, and 0.11 for regulation of emotion.

Changes in EI scores by group.

| - | Group | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (Ν=51; 50.5%) |

Intervention (Ν=50; 49.5%) |

|||

| N (%) | N (%) | |||

| Gender | - | - | - | |

| Men | 4 (7.8) | 7 (14.0) | 0.321+ | |

| Women | 47 (92.2) | 43 (86.0) | ||

| Age, mean (SD) | 41.2 (9.3) | 40.1 (6.4) | 0.478 ‡ | |

| Family status | - | - | - | |

| Unmarried | 16 (31.4) | 9 (18.0) | 0.313++ | |

| Married | 33 (64.7) | 37 (74.0) | ||

| Divorced | 1 (2.0) | 3 (6.0) | ||

| Widowed | 1 (2.0) | 1 (2.0) | ||

| Educational level | - | - | - | |

| Technological university | 23 (45.1) | 22 (44.0) | 0.939+ | |

| University | 6 (11.8) | 5 (10.0) | ||

| MSc | 22 (43.1) | 23 (46.0) | ||

| Specialty | 4 (7.8) | 6 (12.0) | 0.525++ | |

| Working position | - | - | - | |

| Employee | 41 (80.4) | 42 (84.0) | 0.636+ | |

| Supervisors | 10 (19.6) | 8 (16.0) | ||

| Primary care facility | - | - | - | |

| Health center | 41 (80.4) | 42 (84.0) | 0.715++ | |

| Local Health Groups | 8 (15.7) | 5 (10.0) | ||

| Other | 2 (3.9) | 3 (6.0) | ||

| Working status: | - | - | - | |

| Permanent employee | 31 (60.8) | 35 (70.0) | 0.331+ | |

| Contract employee | 20 (39.2) | 15 (30.0) | ||

| Working shift | - | - | - | |

| Morning | 13 (25.5) | 10 (20.0) | 0.063+ | |

| Morning and afternoon | 17 (33.3) | 28 (56.0) | ||

| 24h | 21 (41.2) | 12 (24.0) | ||

| Years of working experience as a nurse | - | - | - | |

| 1-10 | 19 (37.3) | 12 (24.0) | 0.082++ | |

| 11-20 | 16 (31.4) | 28 (56.0) | ||

| 21-30 | 11 (21.6) | 8 (16.0) | ||

| 31+ | 5 (9.8) | 2 (4.0) | ||

| Job satisfaction | - | - | - | |

| None | 2 (3.9) | 1 (2.0) | 0.383++ | |

| A little | 2 (3.9) | 7 (14.0) | ||

| Moderate | 22 (43.1) | 11 (22.0) | ||

| Much | 18 (35.3) | 21 (42.0) | ||

| Very much | 7 (13.7) | 10 (20.0) | ||

| - | Group | P+ | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Intervention | ||||||

| N | % | N | % | ||||

| Salary benefits | Not at all | 2 | 3.9 | 1 | 2.0 | 0,711 | |

| Slightly | 6 | 11.8 | 4 | 8.0 | |||

| Moderately | 10 | 19.6 | 11 | 22.0 | |||

| Very | 13 | 25.5 | 14 | 28.0 | |||

| Very much | 20 | 39.2 | 20 | 40.0 | |||

| Teamwork/collaboration between colleagues | Not at all | 2 | 3.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 0,514 | |

| Slightly | 2 | 3.9 | 1 | 2.0 | |||

| Moderately | 4 | 7.8 | 5 | 10.0 | |||

| Very | 21 | 41.2 | 20 | 40.0 | |||

| Very much | 22 | 43.1 | 24 | 48.0 | |||

| Collaborativeness/good interpersonal relationships | Not at all | 1 | 2.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0,495 | |

| Slightly | 2 | 3.9 | 2 | 4.0 | |||

| Moderately | 6 | 11.8 | 4 | 8.0 | |||

| Very | 19 | 37.3 | 19 | 38.0 | |||

| Very much | 23 | 45.1 | 25 | 50.0 | |||

| Project recognition/reward from management | Not at all | 6 | 11.8 | 3 | 6.0 | 0,668 | |

| Slightly | 5 | 9.8 | 5 | 10.0 | |||

| Moderately | 8 | 15.7 | 7 | 14.0 | |||

| Very | 12 | 23.5 | 16 | 32.0 | |||

| Very much | 20 | 39.2 | 19 | 38.0 | |||

| Project recognition/reward from patients | Not at all | 3 | 5.9 | 1 | 2,0 | 0,588 | |

| Slightly | 5 | 9.8 | 1 | 2,0 | |||

| Moderately | 3 | 5.9 | 11 | 22.0 | |||

| Very | 11 | 21.6 | 13 | 26.0 | |||

| Very much | 29 | 56.9 | 24 | 48.0 | |||

| Utilization of skills/qualifications | Not at all | 3 | 5.9 | 1 | 2.0 | 0,304 | |

| Slightly | 2 | 3.9 | 3 | 6.0 | |||

| Moderately | 13 | 25.5 | 8 | 16.0 | |||

| Very | 14 | 27.5 | 16 | 32.0 | |||

| Very much | 19 | 37.3 | 22 | 44.0 | |||

| Development opportunities/incentives | Not at all | 6 | 11.8 | 2 | 4.0 | 0,112 | |

| Slightly | 7 | 13.7 | 5 | 10.0 | |||

| Moderately | 14 | 27.5 | 12 | 24.0 | |||

| Very | 10 | 19.6 | 13 | 26.0 | |||

| Very much | 14 | 27.5 | 18 | 36.0 | |||

| Good working conditions (logistical equipment) | Not at all | 5 | 9.8 | 1 | 2.0 | 0,033 | |

| Slightly | 5 | 9.8 | 2 | 4.0 | |||

| Moderately | 9 | 17.6 | 9 | 18.0 | |||

| Very | 16 | 31.4 | 13 | 26.0 | |||

| Very much | 16 | 31.4 | 25 | 50.0 | |||

| Adequacy of staff | Not at all | 6 | 11.8 | 2 | 4.0 | 0.628 | |

| Slightly | 7 | 13.7 | 1 | 2.0 | |||

| Moderately | 5 | 9.8 | 11 | 22.0 | |||

| Very | 9 | 17.6 | 15 | 30.0 | |||

| Very much | 24 | 47.1 | 21 | 42.0 | |||

| Permanence in the public sector | Not at all | 10 | 19.6 | 3 | 6.0 | 0.464 | |

| Slightly | 2 | 3.9 | 4 | 8.0 | |||

| Moderately | 8 | 15.7 | 11 | 22.0 | |||

| Very | 16 | 31.4 | 16 | 32.0 | |||

| Very much | 15 | 29.4 | 16 | 32.0 | |||

Before the intervention, the scores of the participants in the “self-emotion appraisal” dimension did not differ significantly depending on the elements in the table above. After the intervention, the score did not differ significantly according to the elements in the table above. Over time, the score in the “self-emotion appraisal” dimension increased significantly in men and women, in participants who were under 40 years old, in those who had a university education or holders of a master's degree, in those who did not have a specialty, in those who worked in a health center, in permanent employees, in those who had rotating shifts, in those with 11-20 years of service, and in those who were not at all to moderately satisfied with their work in general (Table 4).

| - | Group | Pre | Post | Change | P2 | P3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||||

| Self emotion appraisal | Control | 5.49 (0.95) | 5.54 (0.87) | 0.05 (0.6) | 0.640 | 0.049 |

| Intervention | 5.59 (0.91) | 5.97 (0.67) | 0.38 (1.00) | 0.001 | - | |

| - | P1 | 0.588 | 0.007 | - | - | - |

| Emotion appraisal of others | Control | 5.54 (0.94) | 5.39 (0.92) | -0.15 (0.63) | 0.161 | 0.005 |

| Intervention | 5.63 (0.88) | 5.9 (0.67) | 0.27 (0.84) | 0.011 | - | |

| P1 | 0.631 | 0.002 | - | - | - | |

| Use of emotion | Control | 5.38 (1.14) | 5.33 (1.11) | 0.03 (0.67) | 0.679 | 0.022 |

| Intervention | 5.39 (1.02) | 5.74 (0.88) | 0.26 (1.01) | 0.005 | - | |

| P1 | 0.944 | 0.044 | - | - | - | |

| Regulation of emotion | Control | 4.85 (1.24) | 4.78 (1.22) | -0.06 (0.83) | 0.637 | 0.026 |

| Intervention | 4.88 (1.15) | 5.25 (0.96) | 0.37 (1.08) | 0.008 | - | |

| P1 | 0.886 | 0.035 | - | - | - |

| - | Self Emotion Appraisal | P2 | P3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Change | ||||

| Mean (SD) |

Mean (SD) |

Mean (SD) |

||||

| Gender |

Men | 5.15 (0.89) | 6.04 (0.6) | 0.89 (1.31) | 0.021 | 0.149 |

| Women | 5.66 (0.9) | 5.96 (0.68) | 0.3 (0.93) | 0.050 | - | |

| P1 | 0.167 | 0.782 | - | - | - | |

| Age |

<40 | 5.38 (0.92) | 5.92 (0.75) | 0.54 (1.08) | 0.009 | 0.264 |

| >=40 | 5.8 (0.86) | 6.02 (0.58) | 0.22 (0.91) | 0.275 | - | |

| P1 | 0.104 | 0.601 | - | - | - | |

| Educational level |

Τ.Ε. | 5.54 (1.1) | 5.91 (0.74) | 0.37 (1.12) | 0.089 | 0.970 |

| U.Ε./ Postgraduate | 5.63 (0.74) | 6.02 (0.62) | 0.38 (0.91) | 0.050 | - | |

| P1 | 0.709 | 0.573 | - | - | - | |

| Specialty |

No | 5.57 (0.94) | 5.99 (0.69) | 0.42 (1.02) | 0.008 | 0.435 |

| Yes | 5.76 (0.65) | 5.83 (0.52) | 0.08 (0.86) | 0.852 | - | |

| P1 | 0.638 | 0.598 | - | - | - | |

| Primary care facility | Health Center | 5.64 (0.9) | 5.96 (0.62) | 0.32 (0.92) | 0.043 | 0.346 |

| Other | 5.31 (0.97) | 6 (0.93) | 0.69 (1.38) | 0.058 | - | |

| P1 | 0.350 | 0.891 | - | - | - | |

| Working Status |

Permanent employee | 5.61 (0.87) | 5.98 (0.63) | 0.37 (0.95) | 0.035 | 0.924 |

| Contract employee | 5.55 (1.03) | 5.95 (0.78) | 0.4 (1.14) | 0.131 | - | |

| P1 | 0.838 | 0.891 | - | - | - | |

| Working Shift | Morning shift | 5.78 (0.83) | 5.9 (0.52) | 0.12 (0.5) | 0.695 | 0.374 |

| Rotating shift | 5.54 (0.93) | 5.99 (0.7) | 0.44 (1.08) | 0.007 | - | |

| P1 | 0.479 | 0.715 | - | - | - | |

| Years of working experience as a nurse | 1-10 | 5.58 (0.79) | 5.73 (0.7) | 0.15 (0.89) | 0.613 | 0.284 |

| 11-20 | 5.39 (0.95) | 5.97 (0.69) | 0.58 (1.09) | 0.003 | - | |

| >20 | 6.15 (0.75) | 6.25 (0.49) | 0.1 (0.77) | 0.752 | - | |

| P1 | 0.076 | 0.192 | - | - | - | |

| Job Satisfaction | Not at all to Moderately | 5.5 (0.91) | 5.97 (0.59) | 0.47 (1.07) | 0.005 | 0.213 |

| Very/ Very much | 5.95 (0.84) | 5.98 (0.95) | 0.03 (0.57) | 0.937 | - | |

| P1 | 0.165 | 0.979 | - | - | - | |

3p-value for repeated ANOVA measurements. T.Ε., technological education; U.E., university education.

The degrees of change in this dimension did not differ significantly according to the data in the table above. In the “emotion appraisal of others” dimension, the participants’ scores did not differ significantly before and after the intervention. Over time, the score in the “emotion appraisal of others” dimension increased significantly in men, in participants under 40 years old, in those without a specialty, in those working in other primary care facilities, in those who had rotating shifts, in those with 11-20 years of service, and in those who were not at all to moderately satisfied with their work in general (Table 5).

| - | Emotion Appraisal of Others | P2 | P3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Change | ||||

| Mean (SD) |

Mean (SD) |

Mean (SD) |

||||

| Gender | Men | 5.05 (0.85) | 5.71(0.64) | 0.67(0.95) | 0.040 | 0.186 |

| Women | 5.72 (0.85) | 5.93 (0.68) | 0.21 (0.82) | 0.108 | - | |

| P1 | 0.059 | 0.433 | - | - | - | |

| Age |

<40 | 5.59 (0.73) | 6.01 (0.54) | 0.42 (0.8) | 0.017 | 0.234 |

| >=40 | 5.66 (1.02) | 5.79 (0.77) | 0.13 (0.88) | 0.443 | - | |

| P1 | 0.791 | 0.248 | - | - | - | |

| Educational Level |

Τ.Ε. | 5.54 (0.98) | 5.77 (0.6) | 0.23 (1) | 0.202 | 0.778 |

| U.Ε./ Postgraduate | 5.7 (0.8) | 6 (0.71) | 0.3 (0.72) | 0.065 | - | |

| P1 | 0.531 | 0.236 | - | - | - | |

| Specialty |

No | 5.65 (0.9) | 5.94 (0.65) | 0.28 (0.82) | 0.032 | 0.810 |

| Yes | 5.43(0.76) | 5.63 (0.83) | 0.19 (1.08) | 0.579 | - | |

| P1 | 0.564 | 0.287 | - | - | - | |

| Primary Care Facility | Health Center | 5.65 (0.89) | 5.86 (0.71) | 0.21 (0.83) | 0.117 | 0.202 |

| Other | 5.5 (0.87) | 6.13 (0.35) | 0.63 (0.91) | 0.040 | - | |

| P1 | 0.660 | 0.304 | - | - | - | |

| Working Status |

Permanent employee | 5.59 (0.92) | 5.87 (0.72) | 0.28 (0.85) | 0.055 | 0.900 |

| Contract employee | 5.72 (0.79) | 5.97 (0.54) | 0.25 (0.85) | 0.262 | - | |

| P1 | 0.639 | 0.649 | - | - | - | |

| Working Shift |

Morning Shift | 5.7 (0.9) | 5.78(0.56) | 0.08(0.64) | 0.781 | 0.412 |

| Rotating shift | 5.61 (0.88) | 5.93 (0.7) | 0.32 (0.89) | 0.020 | - | |

| P1 | 0.771 | 0.514 | - | - | - | |

| Years of Working Experience as a Nurse | 1-10 | 5.73 (0.55) | 5.88 (0.66) | 0.15 (0.69) | 0.553 | 0.386 |

| 11-20 | 5.43 (1.01) | 5.85 (0.68) | 0.42 (0.87) | 0.012 | - | |

| >20 | 6.05(0.66) | 6.08 (0.68) | 0.02 (0.92) | 0.926 | - | |

| P1 | 0.144 | 0.656 | - | - | - | |

| Job Satisfaction |

Not at all to Moderately | 5.55 (0.87) | 5.87 (0.64) | 0.32 (0.92) | 0.020 | 0.412 |

| Very/ Very much | 5.95 (0.86) | 6.03 (0.8) | 0.08 (0.39) | 0.781 | - | |

| P1 | 0.195 | 0.514 | - | - | - | |

3p-value for repeated ANOVA measurements. T.Ε., technological education; U.E., university education.

The degrees of change in this dimension did not differ significantly according to the data in the table above. Before the intervention, the score in the “use of emotion” dimension did not differ significantly. After the intervention, participants with more than 20 years of service had a significantly lower score compared to those with a maximum of 10 years of service (p=0.028), as obtained after Bonferroni correction. The scores of the rest of the elements in the table did not differ significantly after the intervention. Over time, the score in the “use of emotion” dimension increased significantly in men, in participants who were at least 40 years old, in those who had a university education or a master's degree, in those without a specialty, in those working in other primary care facilities, in permanent employees, in those with 11-20 years of service, and in those who were not at all to moderately satisfied with their work in general (Table 6).

The degrees of change in this dimension differed significantly according to gender, and in particular, the greatest increase occurred in men. Before and after the intervention, the scores of the participants in the “regulation of emotion” dimension did not differ significantly (Table 7).

Over time, the score on the “regulation of emotion” dimension increased significantly in women, in participants under 40 years of age, in those who had a university education or a postgraduate degree, in those without a specialty, in those working in other primary care facilities, in those who had rotating shifts, in those with 11-20 years of service, and in those who were not at all to moderately satisfied with their work in general. The degrees of change in this dimension did not differ significantly according to the data in the table above.

Table 6.

| - | Use of Emotion | P2 | P3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Change | ||||

| Mean (SD) |

Mean (SD) |

Mean (SD) |

||||

| Gender | Men | 4.91 (0.8) | 5.96(0.68) | 1.05(0.92) | 0.006 | 0.044 |

| Women | 5.47 (1.04) | 5.7 (0.91) | 0.23(0.98) | 0.135 | - | |

| P1 | 0.182 | 0.464 | - | - | - | |

| Age |

<40 | 5.37 (0.77) | 5.6 (0.95) | 0.23 (1) | 0.253 | 0.456 |

| >=40 | 5.42 (1.24) | 5.87 (0.8) | 0.45(1.02) | 0.031 | - | |

| P1 | 0.852 | 0.283 | - | - | - | |

| Educational Level |

Τ.Ε. | 5.24 (1.08) | 5.49 (0.92) | 0.24 (1.2) | 0.266 | 0.546 |

| U.Ε./ Postgraduate | 5.51 (0.98) | 5.93 (0.81) | 0.42(0.85) | 0.034 | - | |

| P1 | 0.369 | 0.080 | - | - | - | |

| Specialty |

No | 5.44 (1.04) | 5.78 (0.88) | 0.34(1.06) | 0.031 | 0.979 |

| Yes | 5.02 (0.88) | 5.38 (0.9) | 0.35 (0.63) | 0.401 | - | |

| P1 | 0.349 | 0.291 | - | - | - | |

| Primary Care Facility | Health Center | 5.44 (1.06) | 5.69 (0.91) | 0.25(1.01) | 0.114 | 0.126 |

| Other | 5.13 (0.81) | 5.97 (0.71) | 0.84(0.93) | 0.020 | - | |

| P1 | 0.424 | 0.419 | - | - | - | |

| Working Status |

Permanent employee | 5.34 (1.1) | 5.85 (0.77) | 0.51 (0.9) | 0.004 | 0.071 |

| Contract employee | 5.52 (0.84) | 5.47 (1.09) | -0.05(1.16) | 0.845 | - | |

| P1 | 0.580 | 0.161 | - | - | - | |

| Working Shift |

Morning shift | 5.35 (1.12) | 5.8 (0.9) | 0.45 (0.76) | 0.169 | 0.710 |

| Rotating shift | 5.4 (1.01) | 5.72 (0.89) | 0.32(1.07) | 0.056 | - | |

| P1 | 0.884 | 0.797 | - | - | - | |

| Years of Working Experience as a Nurse | 1-10 | 5.42 (0.83) | 5.23 (1.09) | -0.19(1.07) | 0.508 | 0.070 |

| 11-20 | 5.18 (1.16) | 5.79 (0.74) | 0.6 (1.04) | 0.002 | - | |

| >20 | 5.95 (0.56) | 6.2 (0.73) | 0.25(0.55) | 0.421 | - | |

| P1 | 0.124 | 0.029 | - | - | - | |

| Job Satisfaction |

Not at all to Moderately | 5.27 (1.03) | 5.73 (0.77) | 0.46(0.94) | 0.005 | 0.102 |

| Very/ Very much | 5.9 (0.86) | 5.78 (1.29) | -0.13(1.18) | 0.692 | - | |

| P1 | 0.079 | 0.874 | - | - | - | |

3p-value for repeated ANOVA measurements. T.Ε., technological education; U.E., university education.

| - | Regulation of Emotion | P2 | P3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Change | ||||

| Mean (SD) |

Mean (SD) |

Mean (SD) |

||||

| Gender |

Men | 4.23 (1.31) | 4.75(1.55) | 0.52 (1.9) | 0.212 | 0.692 |

| Women | 4.99 (1.11) | 5.33(0.83) | 0.34 (0.91) | 0.044 | - | |

| P1 | 0.108 | 0.138 | - | - | - | |

| Age |

<40 | 4.66 (1.08) | 5.18(0.89) | 0.52 (1.12) | 0.021 | 0.337 |

| >=40 | 5.1 (1.2) | 5.32(1.04) | 0.22 (1.03) | 0.312 | - | |

| P1 | 0.185 | 0.611 | - | - | - | |

| Educational Level |

Τ.Ε. | 4.8 (1.3) | 5.09(1.12) | 0.29 (1.22) | 0.216 | 0.657 |

| U.Ε./ Postgraduate | 4.95 (1.04) | 5.38(0.81) | 0.43 (0.97) | 0.042 | - | |

| P1 | 0.662 | 0.303 | - | - | - | |

| Specialty |

No | 4.92 (1.12) | 5.29(0.94) | 0.37 (1.1) | 0.029 | 0.977 |

| Yes | 4.6 (1.44) | 4.96(1.16) | 0.36 (0.94) | 0.427 | - | |

| P1 | 0.532 | 0.432 | - | - | - | |

| Primary Care Facility | Health Center | 4.97 (1.18) | 5.21(1.01) | 0.25 (1.01) | 0.134 | 0.069 |

| Other | 4.44 (0.94) | 5.44(0.62) | 1 (1.25) | 0.010 | - | |

| P1 | 0.238 | 0.551 | - | - | - | |

| Working Status |

Permanent employee | 4.92 (1.18) | 5.27 (1) | 0.35 (1.03) | 0.065 | 0.836 |

| Contract employee | 4.78 (1.13) | 5.2 (0.87) | 0.42 (1.22) | 0.144 | - | |

| P1 | 0.695 | 0.812 | - | - | - | |

| Working Shift |

Morning shift | 5 (1.4) | 5.28(0.98) | 0.28 (0.61) | 0.427 | 0.764 |

| Rotating Shift | 4.85 (1.1) | 5.24(0.97) | 0.39 (1.17) | 0.027 | - | |

| P1 | 0.722 | 0.928 | - | - | - | |

| Years of Working Experience as a Nurse | 1-10 | 4.85 (1.02) | 4.9(0.99) | 0.04 (0.92) | 0.894 | 0.493 |

| 11-20 | 4.74 (1.3) | 5.21(0.98) | 0.48 (1.24) | 0.024 | - | |

| >20 | 5.33 (0.78) | 5.78(0.68) | 0.45 (0.7) | 0.195 | - | |

| - | P1 | 0.389 | 0.095 | - | - | - |

| Job Satisfaction |

Not at all to Moderately | 4.75 (1.15) | 5.19 (1) | 0.44 (1.13) | 0.013 | 0.342 |

| Very/ Very much | 5.4 (1.08) | 5.48(0.78) | 0.08 (0.81) | 0.827 | - | |

| P1 | 0.113 | 0.412 | - | - | - | |

3p-value for repeated ANOVA measurements. T.Ε., technological education; U.E., university education.

4. DISCUSSION

The current study aimed to record, investigate, and evaluate EI levels of PHC nurses using an educational intervention. The results of the current study are, nevertheless, promising because they indicate that the educational intervention had a positive effect on the intervention group, as the levels of EI showed significant changes between the first and second measurements. Individuals in the intervention group had higher EI levels, while there were no discernible changes between the two measures in the control group. Particularly, an incremental change was observed with a statistically significant difference between the two measures regarding the intervention group in the dimension of “self-emotion appraisal” on the EI scale, compared to the control group. In the dimension of “emotion appraisal of others”, for the control group, the value during the second measurement was found to be reduced. Regarding the dimension of “use of emotion” and “regulation of emotion”, the change was greater for the intervention group.

In Greece, the research on nursing has been mainly focused on EI in relation to work and psychological parameters and job satisfaction in nurses who work mostly in secondary or tertiary health units. The originality of this study comes from the lack of previous comprehensive research on the EI of nurses working in PHC facilities in Greece. In addition, the above research is a longitudinal experimental study with an educational intervention, where the sample has been separated into an intervention group and a control group. Compared to Greece, at the international level, a clearly greater volume of research and review work was found in relation to the subject of our study or related topics, but it was not at all sufficient for PHC. During the literature review, it was observed that there are many cross-sectional studies but not many longitudinal studies with educational intervention. Some longitudinal research papers with or without educational intervention were found, which had been conducted mainly in universities with a sample of nursing students [22].

The findings of the present study are in line with those of several similar studies [21-25]. Indicatively, the study by Fouad et al. [23] was conducted in Egypt with a sample of 58 students enrolled in the fourth year of study in the Department of Nursing at Damanhour University. The purpose of the research was to investigate the effect of an educational intervention regarding the levels of EI and empathy among students. Two groups were created, namely the intervention group, which consisted of 29 students enrolled in the psychiatric nursing/mental health course, and the control group, which consisted of 29 students enrolled in the community nursing course. The data collection process lasted one month, during which a total of four educational interventions took place, specifically one per week, lasting 90 minutes, on EI-related topics. The educational interventions were carried out only in the intervention group. The results of the survey showed that the mean score of EI in the intervention group increased significantly between the pre-test and post-test after the intervention. In addition, a noticeable difference was observed in the values between the two groups, as the intervention group showed a greater increase in the level of EI compared to the control group. Another longitudinal experimental study that agrees with our findings is the research conducted by Jiménez-Rodríguez et al. [24], which was conducted in Spain with a sample of 60 second-year nursing students of the University of Almeria for the period from October, 2019, to January, 2020. The study aimed to explore the effects of a non-technical skills training program in terms of EI without dividing the sample into intervention and control groups. The questionnaire comprised an EI scale, which the students initially answered. They then completed the questionnaire once more after the training session. The program included 12 courses, three small-group workshops, and several individual exercises. This training was part of the health promotion and safety course, and the content of the program concerned suggestions of general knowledge on topics related to the subject of the study, interspersed with the projection of audio-visual media, working in groups, role-playing, and solving case studies. After the end of the three months of training and after the research process was concluded by completing the questionnaire, it was found that the students during the second phase showed a clearly higher score in all dimensions of EI.

Similar encouraging outcomes were also discovered in the longitudinal study conducted by Budler et al. [25], with the exception that no intervention was used in this research. The survey was conducted among undergraduate nursing students in Slovenia for the periods from November, 2016, to November, 2017, and from November, 2018, to January, 2019. The study sample consisted of 77 students who completed the questionnaire twice, which included a scale measuring EI. The first measurement was carried out during the academic year 2016/2017, while the second measurement, with the same sample of students, was carried out during the academic year 2018/2019. The research findings showed that the levels of EI increased over time, as it was found that students' scores were higher in their 3rd year of the study compared to their 1st year. This is likely due to the fact that as age increases, so does EI. This conclusion is also made by numerous researchers in recent studies [26-32]. Moreover, many claim that persons of a higher level of education have higher EI [30, 33-35]. It has also been found that EI increases proportionally to work experience [33, 35, 36]. All of the above conclusions are confirmed by the findings of our research.

As is demonstrated by numerous studies, EI is characterized by a variety of benefits for both our working and personal lives. In terms of working life, it plays an important part in adopting and exercising effective management, positively correlating it with the adoption of transformational leadership [37]. Studies have shown that people with high EI have better performance at work and higher administrative and leadership skills [38, 39]. Moreover, EI has been associated, on the one hand, with leadership performance and effectiveness and, on the other hand, with good stress management, job satisfaction, prevention of occupational burnout, a good working climate [40], as well as positive forms of conflict [41]. Furthermore, it has been found that EI contributes to the proper management of people's emotional skills and quality of life since it has been positively correlated with well-being, life satisfaction, and resilience [42, 43].

In our study, it was found that job satisfaction was related to all dimensions of EI and that the more satisfied the participants were with their work, the higher levels of EI were observed. According to literature reports, a positive correlation has been found between job satisfaction and life satisfaction [44-47], as well as between work satisfaction and positive emotion [48, 49]. Regarding the research of Konstantinou and Prezerakos [50], the scores of overall and internal satisfaction showed moderate job satisfaction, while the score of external satisfaction was low. External satisfaction mainly concerns the issues of benefits, professional development, and salaries, while internal satisfaction is related to the tasks that employees have, the emotions they feel while performing their work, etc. According to another study by Taskiran et al. [51] in Turkey, in which a cross-sectional study was conducted on 353 nurses, it was found that nurses' intrinsic and overall satisfaction was high, extrinsic satisfaction was low, and their fatigue was intense during the pandemic. In cases where there is low job satisfaction, there is usually no desire to stay in the specific position, and the services provided are of a lower level [52-54]. Additionally, the research by Brofidi et al. [55] and Kanai-Pak et al. [56] found that individuals who had a higher level of education and more years of service while working in unsupportive workplaces expressed frustration and discomfort with their job satisfaction and extended concern for a decrease in the quality of services provided.

It has been demonstrated that the development of emotional regulation skills, a key component of EI, can increase stress tolerance and act protectively against the occurrence of detrimental effects, including depression and professional burnout. Thus, the emotional well-being of employees is enhanced through the satisfaction they receive from their life and work [9, 57]. Many reports concern nurse burnout, which negatively affects job satisfaction [58-62]. In our survey, participants were asked about the factors that contribute to their job satisfaction. Teamwork/collaboration among colleagues was found to be the most important factor, followed by camaraderie/good interpersonal relationships and recognition of the work by patients. The findings of the present study are in agreement with those of many researchers in which it was found that teamwork, cooperation between colleagues, and good interpersonal relationships create positive feelings among the members of a group and are a key factor in job satisfaction, as they are positively related to it [63-68]. At the same time, many researchers have highlighted salaried income as one of the strongest factors of job satisfaction. However, in our case, financial earnings were not included among the most important factors that contribute to the job satisfaction of nurses. Nevertheless, employee dissatisfaction due to low pay has been documented in many studies [69-77]. Contrarily, in a study by Tsounis et al. [78], the participants did not evaluate salary as a key satisfaction factor, as also in the study by Wild et al. [66], they reported being satisfied with their earnings, while in other studies these factors did not seem to be related to each other [63, 79].

4.1. Limitations

The survey was conducted at the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic, making it difficult to communicate in person, as at that time, the regional health authorities of Greece, which granted us permission to conduct the survey, were issuing strong recommendations regarding travel, gatherings, and personal contact. The meetings required for the educational intervention were held after notifying the management of each facility, receiving special permission, and, of course, observing all mandatory sanitary measures. Due to these circumstances, the educational intervention was carried out only once with a duration of one hour. Under other circumstances, it would have been possible to conduct a more systematic and comprehensive educational program for EI development with more materials and of a longer duration [80]. Oral training is one teaching method, but experiential exercises, or practical instruction, should also be prioritized in order to enhance social and emotional abilities through experiential exercises [81]. Additional methods may also be combined and applied in EI development programs, including lectures and group discussions, and individualized approaches to practice skills that incorporate role-playing, emotional experiences, and conversation [82]. Furthermore, it should be noted that the pandemic probably affected the psychological status, overall mood, stress, job satisfaction, and general working conditions of nurses; therefore, the findings for that time may vary [83, 84].

As a limitation of the study, it should be mentioned that the Wong and Law scale used to measure EI is a self-report psychometric instrument, i.e., participants subjectively rated EI dimensions according to their own personal beliefs. Someone with specialized knowledge of emotions may not do well on the actual ability assessed by the particular instrument. Moreover, the sample we analyzed had a favorable initial impression of the research process versus those who did not wish to participate. This assumption raises concerns about the generalizability of the findings, which in most studies can hardly be avoided since the consent of the research participants is required. Finally, the research could be conducted in a larger sample that would include more provincial cities where the results of EI may vary, while a 3rd EI measurement could be conducted after some time in order to determine whether the educational intervention has a permanent effect on nurses or not.

CONCLUSION

In the present study, we investigated whether a specifically created intervention could raise nurses' emotional intelligence levels to enhance their work performance and interpersonal interactions among nursing staff, ultimately leading to the provision of higher-quality healthcare services. The results were encouraging, as participants in the intervention group demonstrated significantly higher scores on all dimensions of the EI measure after the educational intervention. The results of the research demonstrate the necessity of developing nurses' EI, as well as the importance of incorporating the EI concept into nursing education. EI can lead to the improvement of nurses' interpersonal relationships and contribute actively and substantially to the improvement of the health services provided and, by extension, to better organization of the health system. Emotional intelligence courses may be included in the Nursing Department curriculum, as well as in similar programs for nursing staff.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

It is hereby acknowledged that all authors have accepted responsibility for the manuscript's content and consented to its submission. They have meticulously reviewed all results and unanimously approved the final version of the manuscript.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| EI | = Emotional Intelligence |

| PCH | = Primary Health Care |

| WLEIS | = Wong and Law Emotional Intelligence Scale |

| IRCT | = Iranian Registry of Clinical Trial |

| SD | = Standard Deviations |

| TE | = Technological Education |

| UE | = University Education |

| COVID-19 | = Corona virus |

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the University of West Attica (No. Prot: 12758-16/02/2022) and the scientific councils of all the health districts of Greece. In addition, the study was registered in the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trial (IRCT reference 20240126060816N1).

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or research committees and with the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki, as revised in 2013.