All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Role Of Socioeconomics, Psychological State, and Attitude Toward Care Giving on Quality of Life of Dependent Patients’ Caregivers in the Northeast of Thailand

Abstract

Background

Caring for patients with dependency is a burden on primary caregivers, which impacts them economically, socially, and psychologically. The perception of caregiving and the psychological state associated with it further contribute to these effects.

Objectives

This cross-sectional analytical study aimed to study the socioeconomic and caregiving burden factors associated with the Quality of Life (QOL) of dependent patients’ caregivers in the Northeastern region of Thailand.

Methodology

A total of 1,335 dependent patients’ caregivers aged 18–59 years in the Northeastern Region of Thailand were selected by multistage random sampling to respond to a self-administered structured questionnaire. The Generalized Linear Mixed Model (GLMM) was performed to identify socioeconomic and caregiving burden factors associated with QOL while controlling the effects of covariates, presenting Adjusted Odds Ratio (AOR) and 95% Confidence Intervals (CI).

Results

Among 1,335 dependent patients’ caregivers, more than half of them had poor QOL (58.05%; 95% CI:39.28 - 44.65). Factors associated with poor QOL were age 46-59 years (AOR=4.30; 95% CI: 2.84-6.51, p-value<0.001), insufficient financial status with debt (AOR=5.89; 95% CI: 3.85-9.01, p-value<0.001), low caregiving knowledge level (AOR=2.43; 95% CI: 1.63-3.64, p-value<0.001), average to low attitude caregiving level (AOR=4.45; 95% CI: 3.30-5.99, p-value <0.001), and having depression (AOR = 3.57; 95% CI: 1.93-6.59, p-value<0.001).

Conclusion

The findings from this study have important implications for healthcare practice and policy—interventions aimed at improving the QOL of caregivers.

1. INTRODUCTION

The world is evolving toward a transitional society right now. The most prominent example of this pheno- menon has been seen in Thailand, which is anticipated to become “A completely aging society.” It has been in the top 10 Asian countries (Aged Society) since 2000, with 10% of the population being 60 years of age or older. By 2022, this percentage increased to 20% of the total population, and by 2037, it is expected to become a “super-aged society,” with 28% of the population being 60 years of age or older. Thailand's population aged sixty and over increased significantly from 2000 onwards. By 2022, twenty percent of the population was in this age bracket.It is expected to transform into a “super-aged society” by 2037, with 28% of its people being 60 years of age or older. The population of Thailand, which is 60 years of age and older, has increased significantly since 2000. The percentage of people in this age range by 2022 was 20%. Forecasts indicate that by 2037, 28% of Thais will be 60 years of age or older, making the country an aging society.

According to the Mahidol University Institute for Population and Social Research (2022), an increasing number of people worldwide are dealing with chronic health problems because of scientific developments and longer life expectancies. The emphasis on the family members and caregivers of dependent patients has grown because of this shift in the population. Conditions that last a year or more and require continuous medical care limit everyday activities, or both are referred to as chronic illnesses. The following ailments are categorized as chronic diseases by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC): arthritis, type 2 diabetes, cancer, heart disease, stroke, and obesity [1].

The World Health Organization (WHO) has released recommendations intended to help caregivers in their efforts to manage the requirements of people with chronic illnesses properly. The organization recognizes the urgency with which the healthcare system must be mobilized. In order to improve the general well-being and quality of life of people with chronic health issues, caregivers should make sure they have the necessary tools and methods to offer them high-quality care and support [2].

People who are chronically sick frequently have one or more chronic diseases that restrict their abilities, leading to functional reliance. As a result, people with disabilities typically require greater help with everyday tasks2. According to data from Thailand's National Statistical Office, 417,000 individuals were dependent in 2016, making up 3.8% of the country's aged population overall. It is projected that 1,336,000 senior people—or 6.7% of the entire elderly population—will be unable to carry out everyday tasks in 2037 due to chronic illness (The Thailand National Statistical Office, 2016). These dependent people require caregivers to help with both their daily life activities and medical needs. Informal carers, also known as informal caregivers, are unpaid family members who help people who require assistance with daily living tasks, support, and care. Family caregivers are the backbone of systems for providing long-term care and are essential in helping patients who are reliant on them [3].

It is generally accepted that the complex and multifaceted elements impacting caregiver strain are indicators of the need for Long-Term Care (LTC). As of 2019, the National Health Commission Office in Thailand identified the caregiving setting, social context, expec- tations, and resources as important factors.Due to the fact that family caregivers' experiences along the course of the disease and the needs of their care vary, the perception of burden is subjective. The time, energy, and effort demands placed on caregivers are complex and involve a multitude of tasks. These put a lot of strain on the family members, who seem to be the major informal caregivers at the moment. Caregiver load, according to earlier research, is the term used to describe the emotional, psychological, and financial difficulties associated with providing care for a loved one—typically a family member who is ill. Negative health effects, such as higher levels of anxiety and depression, less healthy behaviour, and stress, are directly linked to caregiver load. According to Katsarou, Intas, and Pierrakos [4], caregivers who live with chronically sick individuals feel stress in their personal lives, social isolation, financial hardship, and intrinsic reward. Moreover, international studies demonstrate the inter- dependence between caregivers and the patients they support, as well as the impact that the patient’s level of functioning and course has on the caregiver’s mental health [5-8]. The duration of the care is also an important factor for the caregiver’s burden, i.e., the longer the care, the greater the caregiver’s burden and burnout; all of these indicate a poor quality of life for the patient's caregivers.

To manage these challenges, Thailand's Ministry of Public Health has promoted home-based care, training family members to assist with daily activities and health management. Despite this, caregivers often face fatigue, stress, physical health issues, and mental health challenges exacerbated by the lack of a designated primary caregiver. Social capital, including social networks and perceived support, plays a crucial role in improving health outcomes and quality of life. However, there is limited research on the quality of life of caregivers in Thailand, particularly in the Northeast region. This study aimed to determine the prevalence of quality of life among caregivers and its related factors to fill this gap and provide insights for developing strategies to enhance caregiver well-being and improve hospital-community cooperation.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study Design and Population

This cross-sectional study was conducted among 1,335 Dependent Patients’ Caregivers aged 18–59 years in the Northeastern Region of Thailand. The survey used multi- stage random sampling to select participants from 4 health regions which represented the total population in the Northeastern region of Thailand. The inclusion criteria were caregivers who were the family members and had at least one year of experience in care. They had to communicate well, be proficient in Thai languages, and be willing to cooperate. Caregivers who did not reside in the area during data collection were excluded from this study.

2.2. Sample Size Calculation and Sampling Method

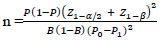

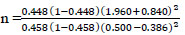

The sample size for this study was calculated using a formula for sample size determination in multivariable analysis, specifically using multiple logistic regression statistics. The data was derived from a study on previous literature on stroke caregiver (Narissara Wongsombat, 2016). The variable of interest was the quality of life of caregivers for patients with dependency. Using the Hsieh, Bloch and Larson (1998). Formula for multivariate analysis in multiple logistic regression:

|

|

n= 600.978

The influence of the relationship between independent variables must be adjusted with the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) value. The researcher selected ρ=0.55 as the minimum sample size for the study because it has a VIF value of 2.22, and the total sample size was 1,335.

Multistage sampling was used. Health regions were the primary sampling unit. Twenty provinces were randomly selected in the second step. Subsequently, district and subdistrict were randomly selected step by step to reach all of the samples.

2.3. Dependent Factors

The dependent variable in this study was the Quality of Life (QOL) of dependent patients’ caregivers (poor/good).

2.4. Operational Definition

Dependent patients are individuals who are unable to perform daily activities independently or are completely disabled, scoring between 0 and less than 11 on the Barthel ADL index as assessed by medical personnel in Northeastern Thailand in 2023. Their caregivers, who are usually family members aged 18-59, assume the primary responsibility of care without receiving any financial compensation from the government or private sector. The duration of care is measured in years, rounded up to one year if it is six months or more. Caregivers' perception of care encompasses their awareness of the challenges and time commitment involved.

The concept of social capital encompasses the strength and readiness of social relationships and roles built on trust and cooperation within the community, including both perceptual and structural aspects. The quality of life for dependent patients is evaluated based on the caregivers' views regarding economic, social, physical, and mental health factors, as well as the social environ- ment. Caregivers' mental health is influenced by their caregiving duties. Personal characteristics such as gender, age, education, religion, marital status, occupation, family size, income, living conditions, and healthcare entitle- ments also play a significant role in their ability to provide care.

2.5. Instrument and Data Collection

The questionnaire development process involved several steps. First, relevant documents, theories, and previous research were reviewed. Next, the content scope was defined to create questionnaires and questions that ensured consistency with research objectives and relevant variables. Then, the quality of life questionnaire used WHOQOL-BREF and the Mental health questionnaire used (CES-D) by Radloff (1977), and the questionnaires were created and reviewed by seven thesis advisors and experts for content validity. The questionnaires were then revised based on feedback and tested with 30 caregivers of dependent patients aged 18-59 to evaluate the quality of the tools before actual implementation.

The validity of the questionnaire was assessed through content validity and reliability. To assess the reliability of the questionnaires, the researcher conducted a try-out pilot study with 30 caregivers of dependent patients aged 18-59, who exhibited characteristics similar to those of the study sample. After the trial pilot study, the reliability was calculated using Cronbach’s Alpha Coefficient, with a reliability of 0.91

2.6. Statistical Analysis

All analyses were performed using Stata version 14.0 (Copyright of Khon Kaen University). Descriptive statistics such as frequency and percentage were used; however, for continuous data, mean, standard deviation, median, and maximum minimum were used. Simple logistic regression was performed to identify individual associations between each independent variable and weight loss product use. Independent factors with a P-value < 0.25 were processed for a Generalized Linear Mixed Model (GLMM) using multi-level analysis to identify the association between factors and QOL of dependent patients’ caregivers when controlling for the effects of other covariates. The 4 health regions were divided into 8 provinces, and provinces were selected as random effects. The magnitude of association was presented as Adjusted Odds Ratios (AORs) and 95% Confidence Intervals (CIs). The significance level was set at P < 0.05.

3. RESULTS

As shown in Table 1, demographic and socioeconomic distribution among dependent patients’ caregivers in the northeastern region of Thailand among 1,335 dependent patients’ caregivers, the majority of the respondents were female (73.26%), 46.44% of them aged between 31–45 years, 54.76% had Primary /equivalent education, 97.53% were Buddhist, 57.83% married, 44.12% were farmers, 44.12% of their average family size was 5 – 6 persons (Tables 1 and 2).

The prevalence of QOL among caregivers of dependent patients. The examination of data from 1,335 caregivers of dependent patients in Thailand's Northeastern area revealed that 58.05 percent of caregivers of dependent patients had a low quality of life (Table 3).

| Personal Characteristics Factors of Caregivers | Quantity | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | ||

| Male | 357 | 26.74 |

| Female | 978 | 73.26 |

| 2. Age Group (years) | ||

| 18 - 30 | 199 | 14.91 |

| 31 – 45 | 620 | 46.44 |

| 45 – 59 | 516 | 38.65 |

| Mean (S.D.) | 46.55 | (12.77) |

| Median (Min: Max) | 47 | (20: 59) |

| 3. Education Level | ||

| No formal education | 45 | 3.37 |

| Primary /equivalent | 731 | 54.76 |

| Secondary/equivalent | 192 | 14.38 |

| High school/equivalent | 219 | 16.40 |

| Bachelor's degree | 115 | 8.61 |

| Postgraduate degree | 33 | 2.47 |

| 4. Religion | ||

| Christian | 33 | 2.47 |

| Buddhist | 1,302 | 97.53 |

| 5. Marital Status | ||

| Marital Status | 31 | 2.32 |

| Married | 772 | 57.83 |

| Divorced | 163 | 12.21 |

| Widowed | 369 | 27.64 |

| 6. Occupation | ||

| Government officer/State enterprise employee | 72 | 5.39 |

| Employee/Freelance | 265 | 19.85 |

| Unemployed | 409 | 30.64 |

| Farmer/Fisherman | 589 | 44.12 |

| 7. Family Size (person) | ||

| < 3 | 203 | 15.21 |

| 3 - 4 | 443 | 33.18 |

| 5 - 6 | 535 | 40.07 |

| > 6 | 154 | 11.54 |

| 8. Average Monthly Income (THB) | ||

| < 5,000 | 127 | 9.51 |

| 5,000 - 15,000 | 861 | 64.49 |

| 15,001 - 30,000 | 240 | 17.98 |

| > 30,000 | 107 | 8.01 |

| Mean (S.D.) | 13,442.1 | (10,605.86) |

| Median (Min: Max) | 10,000 | (1,600: 50,000) |

| 9. Type of Residence | ||

| Rented house/room | 22 | 1.65 |

| Commercial building | 74 | 5.54 |

| Two story house | 608 | 45.54 |

| Single house | 631 | 47.27 |

| 10. Economic Status | ||

| Sufficient with saving | 34 | 2.55 |

| Sufficient without saving | 184 | 13.78 |

| Insufficient with no debt | 336 | 25.17 |

| Insufficient with debt | 781 | 58.50 |

| 11. Healthcare Coverage | ||

| CSMBS | 26 | 1.95 |

| Social security scheme | 39 | 2.92 |

| Universal health coverage | 1,270 | 95.13 |

| Factors Related to Providing Care | Quantity | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Duration of being a caregiver (years) | |||

| < 5 | 465 | 34.84 | |

| 5 - 10 | 600 | 44.95 | |

| 11 -20 | 199 | 14.91 | |

| > 20 | 71 | 5.32 | |

| Mean (S.D.) | 6.01 | (5.20) | |

| Median (Min: Max) | 4 | (1: 45) | |

| 2. Daily caregiving hours (hours) | |||

| < 4 | 277 | 20.75 | |

| 4 - 8 | 479 | 35.88 | |

| 9 - 12 | 186 | 13.93 | |

| > 13 | 393 | 29.44 | |

| Mean (S.D.) | 10.05 | (8.10) | |

| Median (Min: Max) | 6 | (2: 24) | |

| 3. Patient care activities in a day | |||

| 3.1 Feeding | |||

| Oral feeding | 757 | 56.70 | |

| NG tube feeding | 163 | 12.21 | |

| Oral feeding and NG tube feeding | 415 | 31.09 | |

| 3.2 Body cleaning | |||

| Changing diapers and Bathing | 633 | 47.42 | |

| Changing diapers | 440 | 32.96 | |

| Bathing | 213 | 15.96 | |

| None | 49 | 3.67 | |

| 3.3 Medication Administration | |||

| Oral | 1,052 | 78.80 | |

| Oral | 213 | 15.96 | |

| None | 70 | 5.24 | |

| 3.4. Physical Rehabilitation | |||

| Changing posture and rehabilitation | 521 | 39.03 | |

| movement assistant | 392 | 29.36 | |

| Changing posture | 375 | 28.09 | |

| None | 47 | 3.52 | |

| 3.5 Assisting with excretion | |||

| Urinary catheter care and fecal removal | 832 | 62.32 | |

| Urinary catheter care | 300 | 22.47 | |

| Fecal removal | 152 | 11.39 | |

| None | 51 | 3.82 | |

| 3.6 Pressure Ulcer Care | |||

| None | 1,208 | 90.49 | |

| Bedsore but no wound dressing | 54 | 4.04 | |

| Bedsore wound dressing sometimes | 51 | 3.82 | |

| Bedsore wound dressing daily | 22 | 1.65 | |

| 4. Safe Environment for Patient Care | |||

| 4.1 Bed Rails | |||

| None | 1,003 | 75.13 | |

| Has | 332 | 24.87 | |

| 4.2 Cleaning of Medical Equipment | |||

| None | 1,003 | 75.13 | |

| Cleaning with detergent | 233 | 17.45 | |

| Boiling/steaming | 99 | 7.42 | |

| 5. Impact of Being the Primary Caregiver | |||

| None | 972 | 72.81 | |

| Late for work | 227 | 17.00 | |

| Took leave/absent from work | 72 | 5.39 | |

| , Quit job | 64 | 4.79 | |

| 6. Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | |||

| Underweight (< 18.25) | 30 | 2.25 | |

| Normal (18.25 – 22.99) | 678 | 50.79 | |

| Overweight (23.00 – 24.99) | 214 | 16.03 | |

| Obesity level 1 (25.00 – 29.99) | 356 | 26.67 | |

| Obesity level 2 (> 30) | 57 | 4.27 | |

| Mean (S.D.) | 23.28 | (3.31) | |

| Median (Min: Max) | 22.51 | (17.31: 37.25) | |

| 7. Chronic Diseases | |||

| Had | 928 | 69.51 | |

| None | 407 | 30.49 | |

| 8. Illness in the Past Month | |||

| None | 1,177 | 88.16 | |

| Had | 158 | 11.84 | |

| 9. Hospitalization in the Past Year | |||

| None | 1,229 | 92.06 | |

| Hospitalized | 106 | 7.94 | |

| 10. Accidents in the Past 3 Months | |||

| None | 1,311 | 98.20 | |

| Had accidents | 24 | 1.80 | |

| 11. Perceived Health Status (points) | |||

| Poor- very poor (1-3) | 294 | 22.02 | |

| Moderate (4-6) | 792 | 59.33 | |

| Healthy - very healthy (7-10) | 249 | 18.65 | |

| Mean (S.D.) | 5.80 | (1.60) | |

| Median (Min: Max) | 6 | (3: 10) | |

| 12. Health Services Used | |||

| Sub-district Health Promoting Hospital | 743 | 55.66 | |

| Community hospital | 457 | 34.23 | |

| Private clinic | 96 | 7.19 | |

| General hospital / Regional hospital |

39 | 2.92 | |

| 13. Average Monthly Family Expenses (THB) | |||

| < 5,000 | 55 | 4.12 | |

| 5,000 – 15,000 | 57 | 4.27 | |

| 15,001 – 30,000 | 1,079 | 80.82 | |

| > 30,000 | 144 | 10.79 | |

| Mean (S.D.) | 9,989.21 | (10,523.79) | |

| Median (Min: Max) | 8,000 | (1,200: 60,000) | |

| 14. Average Monthly Family Expenses (THB) | |||

| < 3,000 | 415 | 31.09 | |

| 3,000 – 5,000 | 715 | 53.56 | |

| 5,001 – 10,000 | 93 | 6.97 | |

| > 10,000 | 112 | 8.39 | |

| Mean (S.D.) | 3,791.76 | (5,020.10) | |

| Median (Min: Max) | 3,000 | (500: 50,000) | |

| Level of Knowledge | |||

| Low | 1,170 | 87.64 | |

| Average to High | 165 | 12.36 | |

| Mean (S.D.) | 2.98 | (2.06) | |

| Median (Min: Max) | 3 | (0: 10) | |

| Attitude toward Care giving | |||

| Poor to average | 655 | 49.06 | |

| Good | 680 | 50.94 | |

| Mean (S.D.) | 19.08 | (3.46) | |

| Median (Min: Max) | 18 | (14: 25) | |

| Mental Health Status | |||

| No Depression | 84 | 6.29 | |

| Depression | 1,251 | 93.71 | |

| Mean (S.D.) | 35.51 | (11.50) | |

| Median (Min: Max) | 33 | (20: 63) | |

| Social Capital (Level) | |||

| Low | 594 | 44.49 | |

| Average | 715 | 53.56 | |

| High | 26 | 1.95 | |

| Mean (S.D.) | 197.32 | (46.04) | |

| Median (Min: Max) | 190 | (120: 275) | |

| QOL | n | % | 95%CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Good | 194 | 14.53 | 12.68 - 16.54 |

| Average | 366 | 27.42 | 25.04 - 29.89 |

| Poor | 775 | 58.05 | 39.28 - 44.65 |

4. DISCUSSION

The study identifies several critical factors that significantly affect the Quality Of Life (QOL) of caregivers for dependent patients in Northeastern Thailand. These factors include age, economic status, monthly caregiving expenses, caregiving knowledge level, caregiving perception level, and mental health status. Here is a detailed discussion of each factor (Tables 4-6):

| Personal Characteristics of Caregivers | n |

Percentage of poor QOL |

Crude OR | 95%CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | 0.075 | ||||

| Male | 357 | 54.06 | 1 | 1 | - |

| Female | 978 | 59.51 | 1.26 | 0.97-1.63 | - |

| 2. Age Group (years) | <0.001 | ||||

| 18 - 30 | 199 | 30.15 | 1 | 1 | - |

| 31 – 45 | 620 | 55.00 | 2.83 | 2.01-3.98 | - |

| 45 – 59 | 516 | 72.48 | 6.10 | 4.26-8.74 | - |

| 3. Education Level | 0.156 | ||||

| No formal education | 45 | 46.67 | 1 | 1 | - |

| Primary /equivalent | 731 | 58.41 | 1.60 | 0.87-2.94 | - |

| Secondary/equivalent | 192 | 61.98 | 1.86 | 0.97-3.58 | - |

| High school/equivalent | 219 | 53.42 | 1.31 | 0.69-2.49 | - |

| Bachelor's degree | 115 | 64.35 | 2.06 | 1.02-4.14 | - |

| Postgraduate degree | 33 | 51.52 | 1.21 | 0.49-2.98 | - |

| 4. Religion | 0.443 | ||||

| Christian | 33 | 51.52 | 1 | 1 | - |

| Buddhist | 1,302 | 97.53 | 1.31 | 0.65-2.61 | - |

| 5. Marital Status | 0.616 | ||||

| Single | 31 | 51.61 | 1 | 1 | - |

| Married | 772 | 57.25 | 1.25 | 0.61-2.58 | - |

| Divorced | 369 | 58.54 | 1.32 | 0.63-2.76 | - |

| Widowed | 163 | 61.96 | 1.53 | 0.70-3.30 | - |

| 6. Occupation | <0.001 | ||||

| Unemployed | 409 | 37.65 | 1 | 1 | - |

| Government officer/State enterprise employee |

72 | 58.33 | 2.32 | 1.39-3.86 | - |

| Employee/Freelance | 265 | 64.91 | 3.06 | 2.22-4.22 | - |

| Farmer/Fisherman | 589 | 69.10 | 3.70 | 2.84-4.83 | - |

| 7. Family Size (person) | <0.05 | ||||

| < 3 | 203 | 49.26 | 1 | 1 | - |

| 3 - 6 | 978 | 57.98 | 1.42 | 1.05-1.92 | - |

| > 6 | 154 | 70.13 | 2.42 | 1.55-3.76 | - |

| 8. Average Monthly Income (THB) | <0.001 | ||||

| > 30,000 | 107 | 36.45 | 1 | 1 | - |

| 15,001 – 30,000 | 240 | 51.67 | 1.86 | 1.67-2.97 | - |

| < 15,000 | 988 | 60.94 | 2.84 | 1.87-4.29 | - |

| 9. Type of Residence | 0.593 | ||||

| Commercial building | 74 | 52.70 | 1 | 1 | - |

| Rented house/room | 22 | 54.55 | 1.08 | 0.41-2.80 | - |

| Single and Two-story house | 1,239 | 59.43 | 1.26 | 0.78-2.02 | - |

| 10. Economic Status | <0.001 | ||||

| Sufficient with saving | 34 | 40.22 | 1 | 1 | - |

| Sufficient with out saving | 184 | 44.12 | 2.17 | 1.56-2.45 | - |

| Insufficient with no debt | 336 | 47.02 | 2.32 | 1.94-2.89 | - |

| Insufficient with debt | 781 | 67.61 | 3.10 | 2.23-4.31 | - |

| 11. Healthcare Coverage | 0.486 | ||||

| CSMBS | 26 | 57.72 | 1 | 1 | - |

| Social security scheme | 39 | 64.10 | 1.31 | 0.67-2.54 | - |

| Universal health coverage | 1,270 | 65.38 | 1.38 | 0.61-3.13 | - |

Table 5.

| Factors Related to Providing Care | n |

Percentage of poor QOL |

Crude OR | 95%CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Duration of being a caregiver (years) | 0.468 | ||||

| < 5 - 10 | 1,065 | 57.28 | 1 | 1 | - |

| 11 - 20 | 199 | 60.30 | 1.13 | 0.83 - 1.54 | - |

| > 20 | 71 | 63.38 | 1.29 | 0.78 - 2.12 | - |

| 2. Daily caregiving hours (hours) | <0.001 | ||||

| < 4 | 277 | 37.91 | 1 | 1 | - |

| 4 - 8 | 479 | 54.49 | 1.96 | 1.45-2.65 | - |

| 9 - 12 | 186 | 67.74 | 3.44 | 2.32-5.09 | - |

| > 13 | 393 | 72.01 | 4.21 | 3.04-5.49 | - |

| 3. Patient care activities in a day | - | ||||

| 3.1 Feeding | - | - | - | - | <0.001 |

| Oral feeding | 757 | 47.95 | 1 | 1 | - |

| NG tube feeding | 163 | 52.76 | 1.21 | 1.06-1.70 | - |

| Oral feeding and NG tube | 415 | 78.55 | 3.97 | 3.02-5.23 | - |

| 3.2 Body cleaning | <0.001 | ||||

| None | 49 | 30.61 | 1 | 1 | - |

| Bathing | 213 | 51.64 | 2.61 | 1.24-4.70 | - |

| Changing diapers and bathing | 1,073 | 62.58 | 3.95 | 1.87-6.47 | - |

| 3.3 Medication administration | - | - | - | - | <0.001 |

| None | 70 | 24.29 | 1 | 1 | - |

| Oral | 1,052 | 58.65 | 4.42 | 2.52-7.74 | - |

| NG Tube | 213 | 66.20 | 6.10 | 3.29-11.30 | - |

| 3.4. Physical Rehabilitation | <0.001 | ||||

| None and movement assistant | 422 | 48.10 | 1 | 1 | - |

| Changing posture | 392 | 58.35 | 1.67 | 1.12-1.96 | - |

| Changing posture and rehabilitation | 521 | 67.37 | 2.33 | 1.75-3.10 | - |

| 3.5 Assisting with excretion | <0.01 | ||||

| None | 51 | 50.33 | 1 | 1 | - |

| Urinary catheter care | 300 | 59.35 | 1.44 | 1.12-1.88 | - |

| Urinary catheter care and fecal removal |

984 | 78.43 | 3.59 | 1.77-7.26 | - |

| 3.6 Pressure Ulcer Care | <0.001 | ||||

| None | 1,208 | 55.38 | 1 | 1 | - |

| Bedsore but no wound dressing | 22 | 77.27 | 2.73 | 1.00-7.47 | - |

| Bedsore wound dressing sometimes |

51 | 81.48 | 3.54 | 1.77-7.11 | - |

| Bedsore wound dressing daily | 54 | 89.24 | 6.04 | 2.56-14.27 | - |

| 4. Safe Environment for Patient Care | - | ||||

| 4.1 Bed Rails | <0.05 | ||||

| Has | 332 | 44.28 | 1 | 1 | - |

| None | 1,003 | 62.61 | 2.11 | 1.64-2.71 | - |

| 4.2 Cleaning of Medical Equipment | <0.01 | ||||

| None | 1,003 | 54.24 | 1 | 1 | - |

| Cleaning with detergent | 233 | 66.95 | 1.71 | 1.27-2.31 | - |

| Boiling/steaming | 99 | 75.76 | 2.64 | 1.64-4.24 | - |

| 5. Impact of Being the Primary Caregiver | <0.001 | ||||

| None | 972 | 54.01 | 1 | 1 | - |

| Late for work | 227 | 65.64 | 1.63 | 1.20-2.20 | - |

| Took leave/absent from work, Quit job |

136 | 74.26 | 2.45 | 1.64-3.68 | - |

| 6. Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | < 0.05 | ||||

| Underweight (< 18.25) | 30 | 50.00 | 1 | 1 | - |

| Normal (18.25 – 22.99) | 678 | 56.05 | 1.27 | 0.61-2.65 | - |

| Overweight (23.00 – 24.99) | 214 | 57.01 | 1.33 | 0.62-2.85 | - |

| Obesity level 1 (25.00 – 29.99) | 356 | 59.27 | 1.45 | 0.69-3.07 | - |

| Obesity level 2 (> 30) | 57 | 82.46 | 4.70 | 1.75-12.63 | - |

| 7. Chronic Diseases | <0.01 | ||||

| None | 407 | 41.03 | 1 | 1 | - |

| Had | 928 | 65.52 | 2.73 | 2.15-3.47 | - |

| 8. Illness in the Past Month | 0.051 | ||||

| None | 1,177 | 57.09 | 1 | 1 | - |

| Had | 158 | 65.19 | 1.41 | 0.99-1.99 | - |

| 9. Hospitalization in the Past Year | 0.612 | ||||

| None | 1,229 | 58.85 | 1 | 1 | - |

| Hospitalized | 106 | 60.38 | 1.11 | 0.74-1.66 | - |

| 10. Accidents in the Past 3 Months | 0.191 | ||||

| None | 1,311 | 54.82 | 1 | 1 | - |

| Had accidents | 24 | 70.83 | 1.77 | 0.73-4.30 | - |

| 11. Perceived Health Status (points) | <0.001 | ||||

| Healthy - very healthy (7-10) | 249 | 39.80 | 1 | 1 | - |

| Moderate (4-6) | 792 | 58.84 | 2.16 | 1.64-2.84 | - |

| Poor- very poor (1-3) | 294 | 77.11 | 5.09 | 3.49-7.42 | - |

| 12. Health Services Used | <0.001 | ||||

| General hospital / Regional hospital | 39 | 31.95 | 1 | 1 | - |

| Community hospital | 457 | 67.71 | 4.47 | 2.79-7.15 | - |

| Private clinic | 96 | 69.23 | 4.79 | 2.36-9.73 | - |

| Sub-district Health Promoting Hospital |

743 | 72.27 | 5.55 | 4.31-7.16 | - |

| 13. Average Monthly Family Expenses (THB) | 0.597 | ||||

| < 5,000 | 55 | 53.73 | 1 | 1 | - |

| 5,000 – 15,000 | 57 | 54.39 | 1.07 | 0.51-2.25 | - |

| > 15,000 | 1,223 | 58.46 | 1.26 | 0.73-2.17 | - |

| 14. Average Monthly Family Expenses (THB) | <0.001 | ||||

| < 3,000 | 415 | 42.17 | 1 | 1 | - |

| 3,000 – 5,000 | 715 | 60.98 | 2.14 | 1.67-2.74 | - |

| 5,001 – 10,000 | 93 | 78.49 | 5.00 | 2.94-8.52 | - |

| > 10,000 | 112 | 81.25 | 5.94 | 3.59-9.92 | - |

| Level of Knowledge | <0.001 | ||||

| Average to High | 165 | 33.94 | 1 | 1 | - |

| Low | 1,170 | 61.45 | 3.10 | 2.20-4.37 | - |

| Attitude toward Caregiving | <0.001 | ||||

| Good | 680 | 45.59 | 1 | 1 | - |

| Poor to average | 655 | 70.99 | 2.92 | 2.32-3.66 | - |

| Mental Health Status | <0.001 | ||||

| No Depression | 84 | 22.62 | 1 | 1 | - |

| Depression | 1,251 | 60.43 | 5.22 | 3.09–8.82 | - |

| Social Capital (Level) | 0.059 | ||||

| High | 26 | 51.00 | 1 | 1 | - |

| Average | 715 | 60.98 | 1.56 | 0.71-3.42 | - |

| Low | 594 | 54.88 | 1.22 | 0.55–2.67 | - |

| Factors | n |

Percentage of poor QOL |

Crude OR |

GLMM Adj. OR |

95%CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age Group (years) | <0.001 | |||||

| 18 - 30 | 199 | 30.15 | 1 | 1 | 1 | - |

| 31 – 45 | 620 | 55.00 | 2.69 | 2.70 | 1.83-3.99 | - |

| 45 – 59 | 516 | 72.48 | 6.10 | 4.30 | 2.84-6.51 | - |

| 2. Economic Status | <0.001 | |||||

| Sufficient with saving | 34 | 40.22 | 1 | 1 | 1 | - |

| Sufficient without saving | 184 | 44.12 | 2.17 | 1.96 | 1.48-2.51 | - |

| Insufficient with no debt | 336 | 47.02 | 2.32 | 2.91 | 1.81-4.67 | - |

| Insufficient with debt | 781 | 67.61 | 3.10 | 5.89 | 3.85- 9.01 | - |

| 3. Caregiving Knowledge Level | <0.001 | |||||

| Average to High | 165 | 33.94 | 1 | 1 | 1 | - |

| Low | 1,170 | 61.45 | 3.10 | 2.43 | 1.63-3.64 | - |

| 4. Attitude Level | <0.001 | |||||

| High | 680 | 45.59 | 1 | 1 | 1 | - |

| Average | 655 | 70.99 | 2.92 | 4.45 | 3.30-5.99 | - |

| 5. Mental Health | <0.001 | |||||

| No Depression | 84 | 22.62 | 1 | 1 | 1 | - |

| Depression | 1,251 | 60.43 | 5.22 | 3.57 | 1.93-6.59 | - |

It has been found that caregivers aged 45-59 of dependent patients have a higher likelihood of experiencing poor quality of life compared to other age groups. This finding is consistent with previous studies, both internationally and in Thailand, which have identified age as a significant predictor of caregiver burden. According to Adelman et al. (2014) [9], age is a primary factor in predicting caregiver burden and related distress. Nearly half of the caregivers are working-age individuals whose health deteriorates with age. This aligns with Orem's (1991) [10] concept that age indicates maturity or the ability to manage the environment, mental state, and perception. Age influences a person's self-care ability, which increases until adulthood and may decline in old age. Similarly, a study by Prachuntaen (2018) [11] found that age significantly affects the physical quality of life of elderly caregivers. Factors considered include physical strength, daily caregiving capacity, and significant bodily changes at a 0.05 statistical significance level. The most impactful factor on physical quality of life is daily caregiving capacity. This research indicates that age is a crucial determinant of caregiving ability, decision-making, and overall caregiving capacity, which diminishes with age. Consequently, as caregivers age, their caregiving burden increases, leading to a decline in quality of life and increased difficulty in caregiving.

People with higher incomes are generally able to plan their lives better and choose the four basic necessities of life to meet their needs with higher quality compared to those with lower incomes. Economic and social issues, as well as financial problems or poverty, contribute to stress and anxiety, which in turn affect the quality of life. Moreover, income is an indicator of financial stability. Caregivers must be prepared to cover medical expenses and related activities for dependents. Those with higher incomes who can adequately meet necessary expenses will have a better quality of life compared to caregivers with lower and insufficient incomes. This is consistent with the study by Suttasri et al., which found a moderate positive correlation between income and the quality of life of caregivers of chronic patients with dependencies [12].

The knowledge in caregiving reveals that caregivers with a low level of knowledge tend to have a poor quality of life. The knowledge of patient health care negatively impacts the health care of those who are dependent on the caregiver’s health. This can be explained by the fact that caregivers who provide excellent care for those with health dependency have gained caregiving experience from various media, other individuals, and access to health care services related to patient care. This aligns with Green's concept, which states that knowledge is a fundamental factor that motivates an individual's actions and can lead to personal satisfaction derived from learning experiences. This is also consistent with studies by Ahmed and Ghaith (2018) [13]. which found that internal factors affecting the performance of caregivers for dependent elderly are knowledge of elderly care. This knowledge promotes efficient caregiving, enhances the self-help capacity of those with depen- dencies, and maintains a good quality of life for caregivers.

Perception in caregiving studies shows that moderate perception is associated with a poorer quality of life. This is consistent with the study by Turnbull et al., [14] which examined factors related to caregiving for homebound elderly. They found that perceptions and attitudes towards elderly care were at a moderate level. Additionally, it aligns with the study by Purimat et al. [15], which investigated factors influencing the quality of life of caregivers for dependent elderly in Chanthaburi Province. They found that per- ceptions of elderly care could predict 58.1% of the quality of life of caregivers for dependent elderly. However, this contrasts with the study by Promtingkarn et al.(2019) [16], which found that a positive attitude had the greatest impact on elderly care in the health service system. This study shows that perception in caregiving reflects gratitude and repayment of kindness towards parents, spouses, and others. Haley et al. (2009) [17] found that caregivers feel valued when caring for patients. Factors influencing and predicting the quality of life of caregivers for dependent elderly include the attitude towards elderly care, with self-esteem being the most significant predictor. This can be explained by the fact that caregivers' self-worth and gratitude contribute to their sense of value, and if they are confident in their capabilities and have strong motivation, they can face various challenges and achieve a good quality of life. This is consistent with the study by Saban et al., which found that the perception of self-worth was the most significant predictor of caregivers' quality of life [18].

Mental health of caregivers: Studies have found that depression is associated with a poorer quality of life, which studied the factors predicting stress coping in caregivers of spinal cord injury patients. It found that participants who received correct caregiving information were better able to make appropriate problem-solving decisions, leading to more effective stress coping. Additionally, previous studies have found that caregiver role stress and caregiver attitudes significantly explain the variance in caregiver readiness for caring for dependent elderly. Considering the weight and direction of caregiver role stress, it was found that lower caregiver role stress is associated with higher readiness to care for dependent elderly. Caregiver role stress is the most influential factor in predicting caregiver readiness to care for dependent elderly, leading to mental health problems, depression, and poor quality of life [19].

The burden on primary caregivers is related to the progression of psychiatric disorders and mental health. Common mental health problems in caregivers include anxiety (95%) and depression (45%). Symptoms of severe mental conditions (post-traumatic stress disorder) and psychological distress include feelings of helplessness, uncertainty, hopelessness, loss of dignity, guilt, and impaired quality of life [20].

CONCLUSION

The findings from this study have important implications for healthcare practice and policy. Interventions aimed at improving the QOL of caregivers should focus on:

1. Providing financial support or subsidies to alleviate the economic burden of caregiving.

2. Offering training and educational programs to enhance caregiving knowledge and skills.

3. Promoting positive perceptions of caregiving through counseling and support groups.

4. Ensuring access to mental health services to address and prevent depression among caregivers.

By addressing these factors, it is possible to improve the overall well-being and QOL of caregivers, which in turn can positively impact the care they provide to dependent patients. Future research should continue to understand the impact of diversity on caregivers’ needs for support. It should also continue to develop and evaluate alternative models of care. Family-centered care may be the way forward to optimize care systems’ abilities to meet the heterogeneous needs of family caregivers. Ultimately, caregivers must be supported as they are essential to the well-being of those they care for and to the QOL of them.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

J.P.: Contributed to the study’s concept and design; W.I.: Contributed to the validation; K.T. Wrote, reviewed, and edited the manuscript.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| WHO | = World Health Organization |

| CDC | = Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

| VIF | = Variance Inflation Factor |

| QOL | = Quality of Life |

| AORs | = Adjusted Odds Ratios |

| CIs | = Confidence Intervals |

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

Ethics approval was received from the Khon Kaen University Ethics Committee for Human Research, Thailand (Reference No. HE672057).

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

All human research procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the committee responsible for human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2013.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

All data generated or analyzed during this study are available on request from the corresponding author [T.M.].

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to express sincere appreciation to all dependent patients’ caregivers of eight provinces in Northeastern as well as the directors of each sub-districthealth-promoting hospital for the data collection. Special thanks to the Faculty of Public Health, Khon Kaen University, Thailand, for the academic support.