All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Impact of COVID-19 Infection on Incidence and Exacerbation of Overactive Bladder Symptoms: A Systematic Review

Abstract

Background

The COVID-19 pandemic continues to be a major global health concern. A key factor is the presence of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptors in various organs, including the lungs, heart, bladder, and testicles. These receptors allow the SARS-CoV-2 virus to enter cells, making these organs vulnerable to damage. This vulnerability may explain why some patients experience non-respiratory symptoms. Notably, overactive bladder (OAB) symptoms and a condition called COVID-associated cystitis (CAC) have been reported to negatively affect the quality of life of COVID-19 patients. A systematic review is needed to summarize the current understanding of these urological aspects of SARS-CoV-2 infection, considering both short- and long-term effects.

Methods

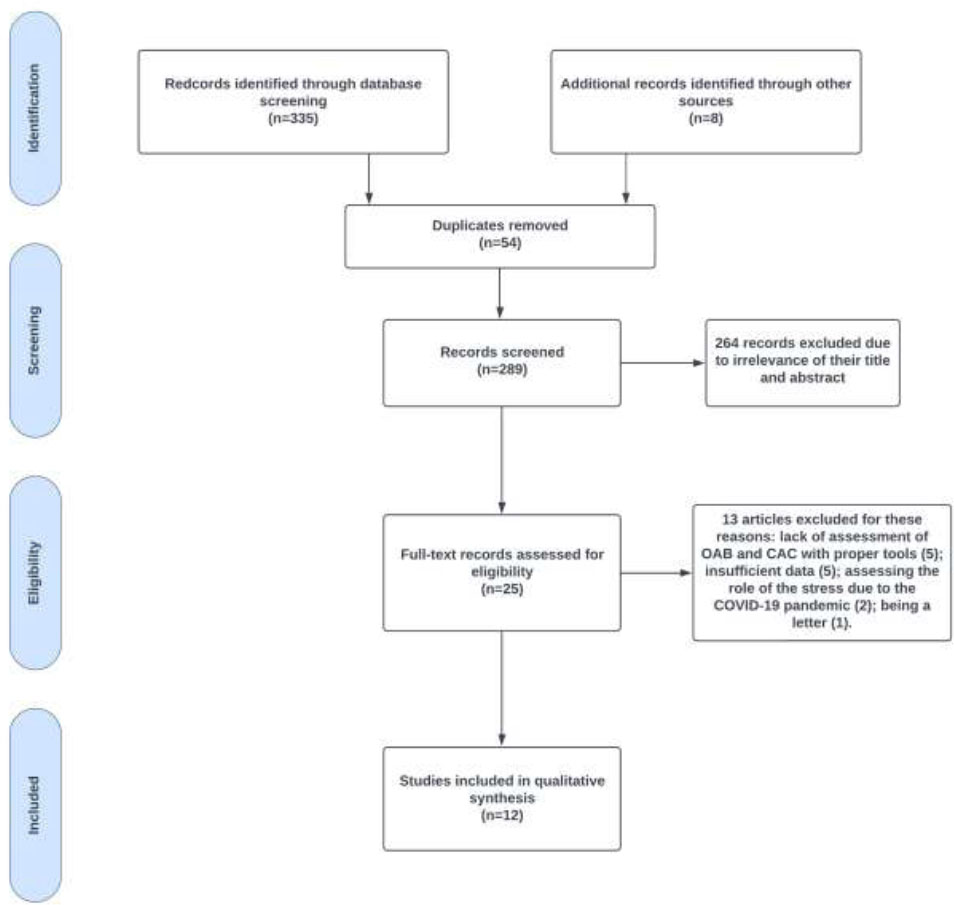

We conducted a systematic review in accordance with PRISMA guidelines to investigate urological complications of COVID-19, with a specific focus on OAB symptoms and CAC (characterized by frequent urination, urgency, and nocturia). We searched databases, including Medline (PubMed), Embase, and Scopus. Two reviewers independently screened the studies, and the quality of each study was assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS).

Results

Our search identified 343 articles published up to March 2024, of which 12 were included in this review. Many of the studies utilized scoring systems such as the International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) and OAB symptom scores. The evidence suggests that COVID-19 may trigger or worsen lower urinary tract symptoms, OAB, and cystitis in some patients, regardless of gender or age. However, these effects appear to be uncommon. Several studies reported an increase in IPSS scores, though it remains unclear whether this increase is temporary or long-lasting. A few studies found that symptoms resolved over several months.

Conclusion

This systematic review suggests that COVID-19 may affect the urinary system, leading to symptoms such as frequent urination, urgency, and nocturia. These symptoms can negatively impact the quality of life in COVID-19 patients.

1. INTRODUCTION

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic has significantly impacted global health. By March 2024, more than four years since its emergence, the virus had reached every continent, infecting an estimated 775 million people and causing approximately 7 million deaths [1, 2]. Healthcare systems have struggled to manage both COVID-19 patients and survivors, many of whom experience lingering symptoms affecting their quality of life. A report by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) indicates that recovered patients often exhibit shortness of breath, fatigue, cognitive problems, cough, chest and abdominal pain, headaches, and urological complications. Research by Bin Cao et al. suggests these complications can persist for at least six months [3]. Similarly, Carfi et al. found that over 87% of survivors experienced various symptoms beyond 60 days after their SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis [4]. Thus, understanding the acute and chronic effects of SARS-CoV-2 remains critical.

The virus enters cells through ACE2 receptors, similar to SARS-CoV. Additionally, it utilizes TMPRSS2 receptors for spike protein priming [5, 6]. RNA sequencing has revealed the presence of these receptors not only in lung cells (type II pneumocytes) but also in the heart, esophagus, kidney tubules, bladder cells, and testicular cells (spermatogonia, Leydig, and Sertoli cells) [7-9]. This widespread presence suggests these organs may be susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 damage, potentially explaining non-respiratory symptoms. While the exact cause of urinary problems in COVID-19 patients is unclear, recent evidence suggests abundant ACE2 expression in bladder cells, making the lower urinary tract a potential target for the virus [7]. There have been numerous reports of COVID-19 patients, including children [10], experiencing new or worsening urinary symptoms, particularly OAB, which has been termed COVID-19-associated cystitis (CAC) [11-13].

Recovery from COVID-19 can take anywhere from a week for mild cases to over six weeks for moderate to severe cases [14]. However, around 80% of recovered patients experience at least one lingering symptom [15]. CAC, considered a long-term COVID manifestation, presents as new or worsening urinary symptoms, primarily aligned with OAB [16]. Symptoms include urgency, frequency, nocturia, dysuria, and/or urge urinary incontinence. Several researchers recommend urological screening of COVID-19 cases, both during the initial infection and afterward, to monitor long-term consequences [5, 17-19].

Thus, a review of the main urological aspects of COVID-19 infection is necessary. This review could uncover new symptoms, raise awareness, and improve the accuracy of COVID-19 diagnosis, as well as identify patients at risk for severe complications. A clearer understanding of the impact on the urinary and urological systems can lead to more evidence-based medical decisions.

2. OBJECTIVE

The goal of this study is to assess the association between SARS-CoV-2 infection and the development or exacerbation of OAB symptoms.

3. METHODOLOGY

Following established methodological guidelines, this systematic review adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [20] to ensure transparent reporting. PRISMA provides a checklist and flow diagram specifically designed for systematic reviews. To enhance credibility, our study was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) (Registration No. CRD42024521011). We aimed to identify and include studies that documented overactive bladder (OAB) symptoms in individuals with either confirmed or ongoing COVID-19 infection. A two-step screening process was implemented to ensure the selection of relevant articles. To maintain methodological rigor, any dis- agreements identified during the search strategy, study selection, or data extraction were addressed through open discussions.

3.1. Search Strategy and Study Selection

A comprehensive search strategy was developed and executed in March 2024 across Medline (PubMed), Embase, and Scopus using the following terms:

(COVID-19 or COVID-19 or Coronavirus or 2019-nCOV or SARS-CoV-2 or post-COVID-19-syndrome or post-COVID-19-condition or post-COVID-syndrome or post-COVID-condition or post-acute-sequelae-of-COVID-19 or long-COVID or long-haul or post-acute-COVID or chronic-COVID or coronavirus-disease-2019 or severe-acute-respi- ratory-syndrome-coronavirus-2) and (COVID-associated-cystitis or overactive-bladder or urinary-frequency or (urinary and urgency) or nocturia or lower-urinary-tract-symptoms or LUTS or IPSS or International-Prostate-Symptom-Score). No language restrictions were applied to the search, and case reports were omitted from the search results.

We supplemented our search by examining the reference lists of the selected studies to identify potentially relevant articles not captured in the initial search. The search findings were imported into EndNote software version 20. Duplicates were removed both automatically and manually, with two reviewers inde- pendently assessing the articles by reviewing their titles and abstracts. Subsequently, the remaining articles were thoroughly evaluated through full-text screening, where disagreements were resolved through consultation with a third reviewer. No protocol was prepared for this review.

3.2. Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

We utilized the PICOS (Participants, Intervention/ Exposure, Comparisons, Outcomes, Study Design) frame- work to establish eligibility criteria for this systematic review. Participants (P) were COVID-19 patients. The focus of the review was on studies assessing the impact of COVID-19 infection (Exposure) on signs and symptoms related to lower urinary tract involvement (O), particularly overactive bladder (OAB) and COVID-associated cystitis (CAC). Studies were included if they reported relevant outcomes (O). All study designs (S) were considered, including prospective and retrospective studies, case series, cross-sectional studies, case-control studies, and cohort studies. However, studies primarily focused on nephrology, psychology, or oncology were excluded.

3.3. Data Extraction

From the selected studies, we extracted relevant data using a standardized data collection form. This data included characteristics of the studies (authors, publication year, study design, sample size, location, study timeframe), participant demographics (age and gender), tools used to assess OAB symptoms (questionnaires) and their corresponding scores, details of reported OAB signs and symptoms, symptom severity scores, the most frequent or bothersome symptoms, as well as information on participant eligibility criteria and comorbidities. Two reviewers independently extracted this information from the selected studies, and discrepancies were resolved through discussion with a third reviewer.

3.4. Quality Assessment

To assess the methodological quality of the included studies, two reviewers independently conducted a bias assessment using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) appropriate for each study design. The NOS assigns scores ranging from zero to nine, with higher scores indicating stronger methodology. Additionally, following the criteria established by Viswanathan et al. [21], we evaluated each study's risk of bias across several domains. Any discrepancies in the quality assessment were resolved through consultation with a third author.

PRISMA flowchart of OAB symptoms in COVID-19 patients and CAC studies.

3.5. Data Synthesis

Data synthesis in this systematic review involved stratification based on questionnaire scores, specifically utilizing the IPSS and OAB questionnaires to screen and monitor urological symptoms, as well as assess quality of life in relation to patient satisfaction with urinary habits. We collected and analyzed IPSS, QoL, and OAB-q scores from various time points (pre-COVID-19, during COVID-19, and post-COVID-19) across the included studies. Additionally, we identified and tabulated the most prevalent urological symptoms documented in each study. Our findings were presented descriptively without statistical analysis.

4. RESULTS

4.1. Study Selection

Our initial search identified 343 potential studies. After reviewing the titles and abstracts, we narrowed this down to 25 articles that appeared relevant based on our defined criteria. Following a full-text review of these articles, an additional thirteen were excluded. This resulted in a final selection of 12 studies for analysis (Fig. 1). These studies encompassed a total of 4100 patients diagnosed with COVID-19 who underwent evaluation for lower urinary tract involvement up to March 2024.

4.2. Overview of Studies’ Characteristics

Table 1 summarizes the demographic characteristics of the study participants. In total, 2284 patients were from the United States, 673 from Italy, 606 from Indonesia, 250 from Turkey, 204 from Jordan, 66 from Greece, and 58 from Mexico. A larger portion of the participants were in the post-acute phase of COVID-19 [16, 22-26]. Only one study reported the severity of COVID-19 infection among patients [27]. A small number of studies included children [27, 28]. The study carried out by Schiavi et al. considered only female patients [29]. Wittenberg et al. and Köse et al. followed up on the patients' symptoms for up to 12 months [24, 30], while Padmanabhan and Roberts et al. followed the patient's symptoms for 28 months [26]. Most of the study designs were cohort studies.

| Study/Ref. | Study Design | Location | N | Age (years) | Time Frame (W/O F/U) | Sex (M: F) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bani-Hani, M., et al. [22] | Prospective | Jordan | 204 | 51.1 ± 17.3 | March 2021 | 204:0 |

| Daryanto, B. et al. [27] | Cross-sectional | Indonesia | 606 | (11-92) | August 2021 | 305:301 |

| Dhar, N., et al. [11] | Case series | USA | 39 | 63.5 (56 - 68.75) | May to June 2020 | 32:7 |

| Jiménez-López, L.A., et al. [23] | prospective, cross-sectional, and analytical | Mexico | 58 | 29 (28–31) | April to December 2021 |

58:0 |

| Kaya, Y., et al. [31] | Retrospective | Turkey | 46 | Female: 32.3 ± 8.9 and Male: 38.9 ± 13 | May to June 2020 | 19:27 |

| Köse, O., et al. [24] | Prospective | Turkey | 42 | 54.76 ± 11.95 | June 2020 to April 2021 | 42:0 |

| Hoang Roberts, L., et al. [16, 26] | Retrospective cohort | USA | 1895 | ≥18 | January 2020 to May 2021 | 312:1548 |

| Schiavi, M.C., et al. [29] | Observational | Italy | 673 | 63.21 ± 10.24 | February 2017 to February 2020 | 0:673 |

| Sevim, M., et al. [32] | Prospective | Turkey | 142 | 72.42 ± 10.21 | June 2021 to December 2021 | 142:0 |

| Tiryaki, S. et al. [28] | Retrospective | Turkey | 20 | 11 ± 5 | November 2020 to May 2021 | 7:13 |

| Wittenberg, S., et al. [30] | Retrospective | USA | 350 | 64 (range 47-82) | May to December 2020 | 210:140 |

| Zachariou A Fau et al. [25] | Case-control | Greece | 66 | Cases: 59.5 (44 -72) Controls: 58.8 (46 – 71) |

December 2020 and May 2021 | 36:30 |

| Study/Ref. | Selection Bias | Performance Bias | Attrition Bias | Detection Bias | Reporting Bias | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| - | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | - |

| Bani-Hani, M., et al. [22] | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 7 |

| Daryanto, B. et al. [27] | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | 6 |

| Dhar, N., et al. [11] | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | 5 |

| Jiménez-López, L.A., et al. [23] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 8 |

| Kaya, Y., et al. [31] | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | 4 |

| Köse, O., et al. [24] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 8 |

| Hoang Roberts, L., et al. [16, 26] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 8 |

| Schiavi, M.C., et al. [29] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 8 |

| Sevim, M., et al. [32] | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 7 |

| Tiryaki, S. et al. [28] | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | 4 |

| Wittenberg, S., et al. [30] | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | 5 |

| Zachariou A Fau et al. [25] | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 7 |

4.3. Quality Assessment and Publication Bias

An assessment of methodological quality using a standardized tool revealed that two studies achieved a high rating [16, 23]. Three studies were rated as moderate quality [24, 29, 30], while the remaining studies received lower quality ratings. Within the selection domain, which comprised four subcategories, two studies received scores for the representativeness of cases [16, 30]. Two studies provided a clear definition of controls [16, 23]. Four articles matched participants based on age [16, 23, 24, 29], one study matched for both sex and age [16], and none matched for education. Additionally, all studies received scores in the exposure domain.

In bias analysis, all studies were deemed to have a low risk of bias in the attrition and reporting bias domains. However, three studies were identified as having a high risk for performance bias [11, 28, 31]. Tables 2-6 provide further details regarding the methodological quality assessment and publication bias.

| - | Selection | Comparability | Outcome | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Study First Author (year) |

Sample Size | Representativeness of the Sample | Non-included Subjects | Subtotal | Anthropometric Measures | Other Factors | Subtotal | Assessment of the Outcome | Statistical Test | Sub-total |

| Daryanto, B. et al. [27] | * | - | * | 2 | - | - | 0 | * | * | 2 |

| - | Selection | Confounder | Outcome | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Study First Author (year) |

Case Definition Adequacy | Representativeness of the Sample | Selection of Controls | Definition of Controls | Subtotal | Age and Sex | Subtotal | Ascertainment of Exposure | Non-response Rate | Sub-total |

| Dhar, N., et al. [11] | * | - | * | - | 2 | - | 0 | * | * | 2 |

| - | Selection | Comparability | Exposure | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| - | Case Definition Adequacy | Representativeness of Cases | Selection of Controls | Definition of Controls | Subtotal | Age | Subtotal | Same Method for Case and Control | Ascertainment of Exposure | Non-response Rate | Sub-total |

| Jimenez-Lopez, L.A., et al. [23] | * | - | * | * | 3 | * | 1 | * | * | * | 3 |

| - | Selection | Confounder | Outcome | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Study First Author (year) |

Outcome of Interest | Representativeness of the Exposed Cohort | Selection of the Non-exposed Cohort | Ascertainment of Exposure | Subtotal | Age and Sex | Subtotal | Assessment of Outcome | Adequate Duration of Follow-up | Adequacy of Follow-up of Cohorts | Sub-total |

| Bani-Hani, M., et al. [22] | * | - | - | * | 2 | - | 0 | * | - | * | 2 |

| Kaya, Y., et al. [31] | * | - | - | * | 2 | - | 0 | * | * | * | 3 |

| Köse, O., et al. [24] | * | - | - | * | 2 | * | 1 | * | * | * | 3 |

| Hoang Roberts, L., et al. [16, 26] | * | * | * | * | 4 | * | 1 | * | * | * | 3 |

| Schiavi, M.C., et al. [29] | * | - | - | * | 2 | * | 1 | * | * | * | 3 |

| Sevim, M., et al. [32] | * | - | - | * | 2 | - | 0 | * | * | * | 3 |

| Tiryaki, S. et al. [28] | * | - | - | * | 2 | - | 0 | * | * | * | 3 |

| Wittenberg, S., et al. [30] | * | * | - | * | 3 | - | 0 | * | * | * | 3 |

4.4. Urinary Symptoms in COVID-19 Patients

Table 7 summarizes different questionnaires adopted by studies, plus results, inclusion and exclusion criteria. In total, six studies used the IPSS form to assess OAB symptoms [22-24, 27, 31, 32]. Five studies used different OAB assessment questionnaires [11, 16, 25, 29, 30]. BBDQ was adopted to assess LUTS in Children [28] and Urinary Symptom Profile was used in one study [31] to assess urinary symptoms in women. Also, 5 studies evaluated QoL in patients [22, 25, 29, 30, 32] and 1 study reported the effects of different medical treatment approaches on urinary symptoms and QoL [29].

4.5. IPSS Questionnaire

The impact of COVID-19 on lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) remains inconclusive. While some studies observed a statistically significant increase in LUTS following COVID-19 infection (Bani-Hani et al. [22], Köse et al. [24], Sevim et al. (in BPH patients taking alpha-blockers) [32], others reported no significant changes (Jiménez-López et al. [23]) or isolated increases in storage symptoms (Kaya et al. [31]). Notably, Köse et al. [24] found that these worsened symptoms persisted in some patients at long-term (3 months and 12 months) follow-ups, with patients over 50 experiencing more severe LUTS during the acute infection. These findings suggest that COVID-19 may exacerbate LUTS in some individuals, particularly older adults, with the specific effects varying across studies.

4.6. OAB Questionnaire

Investigations into the potential association between COVID-19 infection and OAB symptoms have yielded conflicting findings. Several studies reported a rise in OAB symptoms among COVID-19 patients compared to control groups or their pre-infection baselines [11, 16, 25, 29, 30, 33]. These studies employed various OAB assessment tools, yielding findings that reflected a range of increases in symptom scores.

Other studies presented less definitive results. One investigation observed no significant changes in urinary flow rates for women following COVID-19 infection; however, stress incontinence and OAB scores showed significant differences between pre- and post-infection, with increases noted [31].

The persistence of OAB symptoms following COVID-19 infection remains uncertain. In one study [26], the authors suggest potential improvement over time, with scores returning to near baseline levels after 12 months. However, they reported a significant proportion of patients may continue to experience increased OAB symptoms compared to pre-pandemic times [26]. The cause of the potential link between COVID-19 and OAB remains unclear. One study found no correlation between changes in OAB symptomatology and antibody levels [16].

4.7. QoL Questionnaire

Sciavi et al. reported a significant decline in OAB-HRQL scores and patient satisfaction following COVID-19 [29], while Zachariou et al. and Sevim et al. observed an increase in total QOL scores (meaning less satisfaction) in patients after contracting COVID-19 [25, 32]. Also, the study by Wittenberg and Lamb et al. showed a median QOL score of 19 for both men and women with new-onset OAB symptoms post-COVID-19, compared to a lower pre-COVID-19 median score of 9 for patients with worsening OAB (post COVID patients had less satisfaction) and post-COVID-19 score of 20 [30, 33]. In contrast, a study by Bani-Hani et al. found a statistically significant reduction in median QOL scores after COVID-19 infection, which can be regarded as enhanced satisfaction according to the adopted questionnaire [22].

4.8. Most Common Signs

Urinary frequency was the most frequently reported urinary complaint [11, 16, 22, 27, 29, 32], although the reported prevalence varied across studies. Several studies also found that patients experienced increased nocturia [11, 25, 27, 29, 32]. A frequent urge to urinate (urgency) was another urological symptom noted in COVID-19 patients [16, 27, 29]. Dysuria and urinary retention were reported by one author [22]. Interestingly, the severity of these urinary complaints, including frequency, urgency, and nocturia, seemed to be linked to the severity of the infection itself [27]. However, Tiryaki et al. reported no significant relationship between infection severity and duration of urinary symptoms [28]. Overall, the body of research suggests that COVID-19 infection can lead to a variety of urinary issues, with frequent urination being the most common.

| Study [Ref.] | Scoring | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria | Symptom Score | Other Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bani-Hani, M., et al. [22] | IPSS | 1) Male patients confirmed by reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction 2) Able to complete the LUTS questionnaire |

1) ICU patients 2) Unstable patients 3) Urinary incontinence |

IPSS: Increase (P = 0.025) QOL: (P = 0.001) comparing before and during COVID-19 infection |

Increase in frequency of mild and severe symptoms The most common change: augmented urinary frequency (3.4%) followed by dysuria (1.0%), and acute urinary retention (1.0%). |

| Daryanto, B. et al. [27] | IPSS | 1) COVID-19 confirmed by RT-PCR and or by COVID-19 rapid antigen | 1) Patients with urological malignancies 2) A history of urological surgery 3) Patients taking drugs that affect urination patterns |

Greater in men and >50 years old patients (P = 0.000) Positive relationship between COVID-19 severity and IPSS score (R Square = 0,41) |

Positive correlation between comorbidities and degree of IPSS (P = 0.000) The most common change: urinary frequency |

| Dhar, N., et al. [11] | (Overactive Bladder (OAB) Assessment Tool | 1) Confirmed COVID-19 2) Outpatients post-hospital discharge |

1) Positive urine culture 2) Requiring inpatient care |

The median total OAB symptom score in men and women:18 (ranges 12 - 20 and 15 - 21, respectively) | The most common change: increased urinary frequency and nocturia |

| Jiménez-López, L.A., et al. [23] | IPSS | 1) Reproductive-age males 2.1) Confirmed diagnosis of COVID-19 2.2) Healthy participants without previous SARS-CoV-2 infection |

1) Testicular or endocrine diseases 2) Hormonal therapy 3) Previous urinary tract involvement with HBV, HCV, HIV, or former paramyxovirus infection. |

No statistically significant difference (P=0.743) between case and controls. | No correlation between sperm concentration and IPSS (P=0.46) scores of all patients. |

| Kaya, Y., et al. [31] | For men: IPSS For women: Urinary Symptom Profile |

1) COVID-19 patients | 1) Under 18 years old 2) had any type of chronic medical illness or any type of urinary cancer or history of urological operations | Male patients: no statistically significant differences in the total IPSS, the IPSS-V score, and QOL (p=0.148; p=0.933, p=0.079, respectively). Significant difference in IPSS-S scores (p=0.05). |

Female patients: similar low stream scores (p=0.368). Significant difference in the scores of stress incontinence and overactive bladder between the three periods (p=0.05 and p=0.05) |

| Köse, O., et al. [24] | IPSS | 1) PCR COVID-19 positive | 1) Individuals undergoing therapy for BPH or OAB 2) Past experience with urinary tract malignancy or infection 3) Prior surgical intervention on the urinary tract 4) Indwelling urinary catheter |

Increase in the median IPSS (p < 0.001) pre-COVID vs. during COVID-19 | Persistent LUTS developed due to COVID-19 in five patients (14.7%) |

| Hoang Roberts, L., et al. [16] | International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire-overactive bladder (ICIQ-OAB) |

1) Participation in the BLAST COVID study 2) Age 18 yr 3) Agreement to participate in future studies |

1) Decisional impairment 2) Those unable to complete the electronic survey |

Increase compared to before the pandemic (p < 0.001) |

Increase of ICIQ-OAB score in positive serology and PCR-positive patients, compared to uninfected patients (p = 0.0015 and p < 0.0001, respectively) The most common change: frequency (p < 0.0001) and urgency (p < 0.0001 |

| Schiavi, M.C., et al. [29] | OAB-Q, OAB-HRQL, PGI-I | 1) Signed informed consent 2)OAB treatment for 12 weeks or more 3) Answering the questionnaires with the ongoing treatment, within 6 months from the start of the social distancing measures |

1) Urinary incontinence 2) Neurogenic bladder 3) Gynecological tumors 4) Urological cancer 5) Urinary tract infection or chronic inflammation 6) Former pelvic radiotherapy 7) Pelvic organ prolapse grade 8) Interstitial cystitis 9) Bladder pain syndrome 10) Urinary retention 11) Neurologic abnormalities. |

Increase in The OAB symptom scores p < 0.0001), decrease in OAB-HRQL (p < 0.0001). decreased PGI-I during the COVID-19 (p < 0.0001). | Increase in frequency (p < 0.0001), urgent micturition (p < 0.0001), nocturia episodes (p < 0.0001) |

| Sevim, M., et al. [32] | IPSS | 1) Age over 45 2) Confirmed COVID‐19 between June and December 2021 3) Treated with alpha-blockers for BPH |

1) PSA more than 4 ng/dl 2) Former prostate and urethral surgery 3) Diabetes mellitus 4) Patients requiring intensive care monitoring 5) No pre-hospitalization data |

IPSS increased (p < 0.01). QoL scores increased (p < 0.01). | Increased frequency (p < 0.01), nocturia count (p < 0.01), and the mean voiding volume (p < 0.01) |

| Tiryaki, S. et al. [28] | Median bladder and bowel dysfunction questionnaire (BBDQ) | 1) Age under 18 2) COVID-19 or MIS-C at the current exam |

1) No answer 2) Urinary incontinence without any other symptoms 3) Positive urine culture |

Increased score (p < 0.001) pre-COVID- vs during symptoms. | Age and sex Not correlated with the incidence of symptoms The timing of onset and duration of symptoms not associated with symptom severity (p Z 0.306 and p Z 0.450 respectively). Total BBDQ scores correlated positively with age. |

| Wittenberg, S., et al. [30] | AUA Urology Care Foundation OAB Assessment Tool | - | - | Higher scores in new-onset post-COVID patients compared to pre-existing symptomatic patients pre-COVID Increased scores in pre-existing OAB patients after infection |

Most patients (new cases and pre-existing OAB cases) reported improvements in symptoms in follow-ups The most common symptom: nocturia |

| Zachariou A Fau et al. [25] | AUA-OAB-tool IPSS | 1) Patients suffering from post-acute COVID-19 syndrome (PACS) transferred to inpatient rehabilitation for long-term care after initial treatment for COVID-19 pathophysiology | 1) Active UTI 2) Bladder or pelvic tumors 3) Stress urinary incontinence 4) Bladder or kidney stones 5) Neurologic disorders affecting bladder function 6) Post-void residual volume over 100 mL |

Increased OAB and QOL scores after infection(P < 0.05 for both) | No significant change in the control group before and during the stay at the center The most common change: nocturia episodes |

4.9. Relationship with Demographics and Comorbidities

In the research by Daryanto et al., the incidence of urinary symptoms was higher in men and patients over 50 years of age [27]. However, Tiryaki et al. reported no significant relationship between age and sex and the severity or incidence of mentioned urinary symptoms in children [28]. Additionally, Daryanto et al. found a higher number of comorbidities is related to higher IPSS scores [27]. Similarly, Roberts et al. reported increased OAB severity in patients with comorbidities and higher body mass indices [16]. In contrast, Zachariou et al. found no significant difference in urinary symptoms between male and female patients in their study population [25].

4.10. Management

Schiavi et al. reported various approaches to managing overactive bladder (OAB) symptoms and the corres- ponding changes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Specifically, the changes in questionnaire scores were as follows: OAB Symptom increased, while HRQL scores decreased in rehabilitation, nutraceuticals, pharmaco- logical agents, and percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation groups compared to before the COVID-19 pandemic. On the contrary, patients undergoing the other two treatment methods (Sacral Neuromodulation and botulinum neurotoxin injection) showed no significant changes in OAB and HRQL scores. Overall, satisfaction with treatment was significantly reduced in the study population [29].

5. DISCUSSION

COVID-19 infection can significantly impact the urinary system in both men and women, leading to notable changes in urination patterns. Patients with COVID-19 often exhibit elevated values in the IPSS and OAB Questionnaire, particularly among those with severe illness. Symptoms such as urinary frequency increase, nocturia, urgency, and incontinence have been reported by several patients. Urinary symptoms, especially OAB symptoms such as urination more than 13 times a day and over 4 times at night, have seriously compromised the quality of life in COVID-19 patients [11]. SARS-CoV-2 infection may cause the incidence of urinary symptoms or worsen existing ones, especially storage symptoms. While some authors consider the pathogenesis of LUTS to be multifactorial [34-36], it remains incompletely understood. SARS-CoV-2 may reach the bladder tissue through the bloodstream or it may propagate from ACE2-expressing cells such as urethral cells [13]. Expression of ACE2 and TMPRSS2 receptors in urological system cells, along with the similarity between SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV has raised substantial concerns about urological complications of COVID-19 since the beginning of the pandemic. Variations in the expression of ACE2 and TMPRSS2 in human tissues result in different organ involvement in COVID-19 [2]. The presence of ACE2 and TMPRSS2 receptors in the urinary bladder suggests a potential mechanism for how the virus may alter cell function in this organ, potentially explaining findings such as increased IPSS and OAB symptoms. In addition to direct viral action, inflammatory responses induced by COVID-19, as evidenced by cytokine storms, may contribute to urological involvement [37]. This inflammatory response could lead to damage within the urinary system, exacerbating symptoms such as LUTS and urinary urgency [38]. The production of reactive oxygen species during SARS-CoV-2 infection could potentially trigger pathways leading to cytokine release and an exaggerated inflammatory response, as suggested by previous studies. This inflammatory cascade may result in cellular damage within the urinary system [39]. Kashi et al. reported the presence of SARS-CoV-2 in urine samples of only less than 5% of the patients across 14 studies [36]. This low rate of detection of the virus in urine samples suggests that the virus needs to utilize another pathway to infect the bladder, namely the urethral endothelial tissue [13, 40]. Also, the secretion of inflammatory cytokines into the urine or bladder tissue may cause CAC [12]. A recent study highlights COVID-19-associated cystitis (CAC) as a growing concern that is increasingly recognized but often overlooked within clinical settings [41]. Hence, the importance of considering new urinary symptoms in the complex symptomatology of COVID‐19 becomes apparent and healthcare providers dealing with COVID-19 patients should be vigilant about the possibility of CAC [42, 43]. Also, the existence of OAB symptoms along with fever may suggest urosepsis as a differential diagnosis of COVID-19 [13]. Concerning gender differences, Daryanto et al. observed that men over the age of 50 appear to be more vulnerable to developing OAB and CAC symptoms following a COVID-19 infection [27]. In contrast, the broader body of research suggests that there is little to no significant difference between male and female patients concerning the likelihood of developing these symptoms, as reflected by the IPSS and OAB-q scores. However, the interpretation of these findings is constrained by the limitations of the studies, such as the focus on single-gender groups and the small number of participants, making it difficult to draw definitive conclusions about potential gender differences in the manifestation of OAB and CAC symptoms after COVID-19 infection. Although the body of research regarding the impact of acute COVID-19 on the incidence and exacerbation of OAB symptoms is fairly conclusive, the long-term effects of the infection and possible therapeutic options require further investigation [30]. Wittenberg et al. demonstrated that a significant majority (87%) of patients with CAC experienced alleviation of symptoms with conservative treatment during a follow-up period of 21-28 months [30]. Correspondingly, Tiryaki et al. observed complete improvement of symptoms over a 6-month follow-up period in a population of patients under the age of 18 who reported suffering from CAC shortly after COVID-19 infection [28]. Despite the significance of this condition and the considerable impact on patients' quality of life, there is a lack of established treatment options and diagnostic tests. Although several treatment strategies have been tested by Schiavi et al., none of them proved effective in enhancing patient satisfaction with their condition and quality of life [29]. The main strategy for CAC management remains the symptom-based approach, focusing on the management of OAB. Recognizing that inflammatory processes may play a central role in the pathogenesis of CAC, treatments involving immuno- modulators that target the regulation of pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines may expedite the healing process [44], though novel treatment options have been proposed [45]. Management of urological patients can also be done through telemedicine to reduce contact and exposure to the virus [46]. Although the mortality rate due to COVID-19 infection has diminished significantly and the emergency regarding dealing with the disease has diminished, the morbidity caused by inflammatory responses, such as urinary symptoms, is still a concern and requires attention from patients and healthcare providers [47, 48]. Consequently, in this systematic review, we gathered the existing evidence regarding the symptoms, prognosis, and management of OAB caused or exacerbated by the SARS- CoV-2 virus and CAC.

The evidence regarding OAB symptoms in SARS-CoV-2-infected patients remains limited. According to bias analysis, seven articles exhibited a low risk of bias, while the remainder demonstrated a moderate risk of bias (refer to Table 2). A considerable number of studies had restricted study populations (specifically for pediatrics) and diverse characteristics in terms of disease severity, comorbidities, prognosis, and treatments received. Additionally, the absence of post-COVID-19 follow-up or extended follow-up intervals presents further limitations [49]. The variation in study methodologies and outcome measures precluded the possibility of conducting a meta-analysis due to the challenges of comparing studies with differing designs and measures. Thus, there is a pressing need for prospective studies characterized by robust methodological quality and extended follow-up periods to discern the enduring impact of long COVID-19 on the urinary system, particularly concerning overactive bladder (OAB) symptoms.

CONCLUSION

While further investigations are warranted, our systematic review revealed potential urological complications associated with COVID-19 and long COVID-19, including alterations in micturition patterns and urinary urgency, alongside other overactive bladder (OAB) symptoms. Significantly elevated International Prostate Symptom Scores (IPSS) and OAB-q scores were observed following COVID-19 infection, accompanied by a decline in patient satisfaction with urination habits as indicated by QOL questionnaires. Fortunately, these complications typically resolved over time and generally did not result in lasting sequelae.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

H.A.: Study conception and design; B.E.: Data collection; S.H.S.: Analysis and interpretation of results; E.N.: Methodology; K.H.: Conceptualization; M.R.: Draft manuscript.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| ACE2 | = Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 |

| OAB | = Overactive bladder |

| CAC | = COVID-associated cystitis |

| NOS | = Newcastle-Ottawa Scale |

| IPSS | = International Prostate Symptom Score |

| PRISMA | = Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| PICOS | = Participants, Intervention/Exposure, Comparisons, Outcomes, Study Design |

| LUTS | = Lower urinary tract symptoms |

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIAL

All the data and supportive information are provided within the article.