All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Stroke Prevention: Exploring the Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices of CHWs and Healthcare Professionals in the North-West Province, South Africa.

Abstract

Background

Stroke is a major global health issue, often preventable with early intervention. Community health workers (CHWs) are vital in primary care and prevention, yet their role in cardiovascular care, particularly stroke prevention, in South Africa is under-researched. Further research is needed to understand their knowledge, attitudes, and practices towards stroke prevention.

Objectives

Objectives of this study included: (1) To explore and describe community health workers’ knowledge, attitudes and practices towards stroke prevention for individuals at risk of cardiovascular disease; (2) To explore and describe healthcare professionals’ perceptions of the knowledge, attitudes and practices community health workers should have to prevent strokes.

Methods

A qualitative, exploratory and descriptive design was followed. Purposive sampling of community health workers, healthcare professionals and community health centres was used. Eight World Café sessions with community health workers (n= 90) and eight focus group discussions with healthcare professionals (n = 49) were held. Cresswell’s six steps of thematic analysis were used.

Results

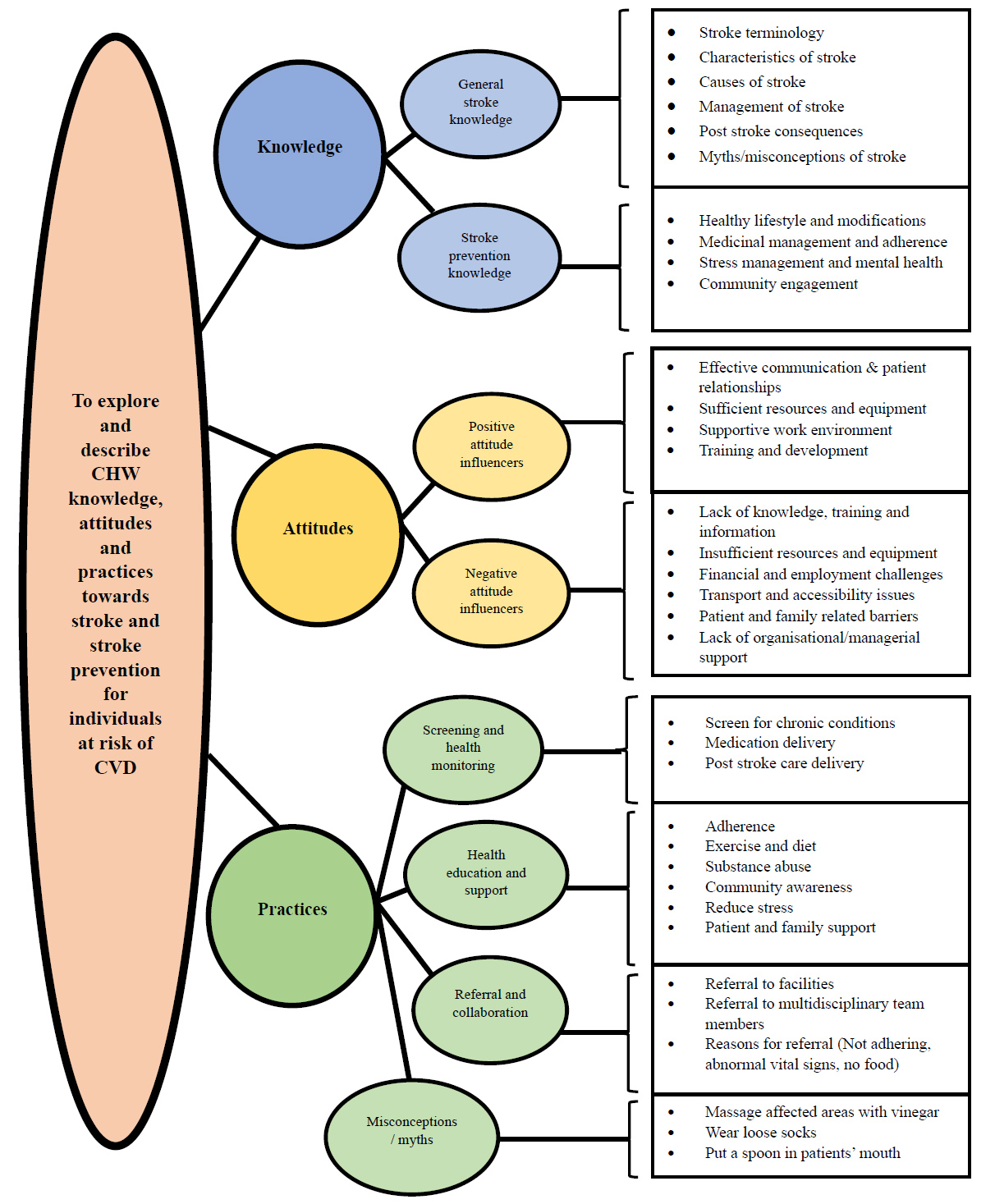

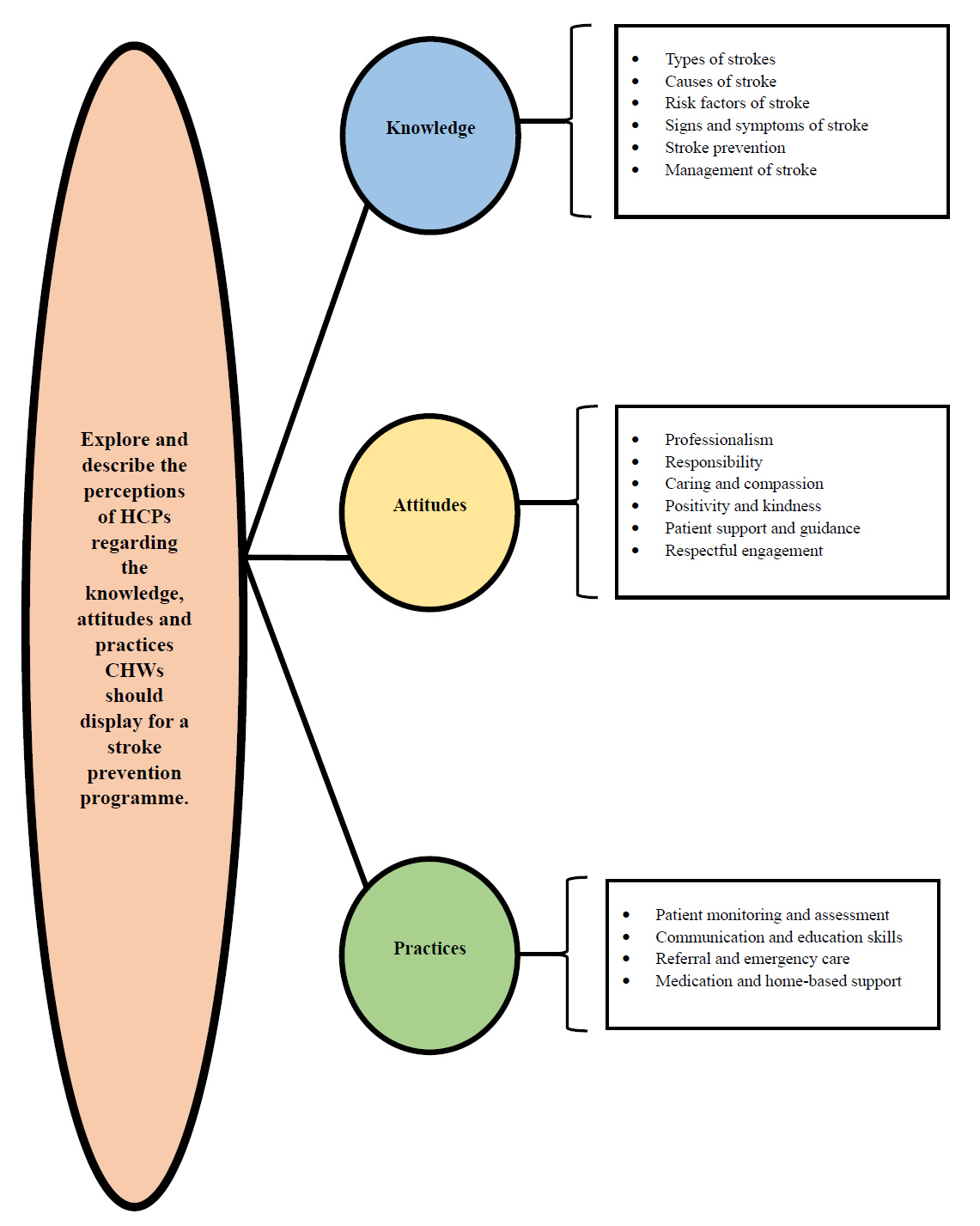

From the World Café sessions and the focus group discussions, three themes with respective subthemes emerged, namely (1) Knowledge, (2) Attitudes and (3) Practices, which mostly corresponded with each other. The data from the focus group discussions were more specific and clinical, owing to the nature of the healthcare professionals’ responses.

Discussion

Under the ‘knowledge’ theme, gaps/misconceptions were identified with regard to Community Health Workers' stroke prevention knowledge. The ‘attitude’ theme revealed that Community Health Workers displayed positive and negative attitude influencers, contributing to or hindering their ability to practice stroke prevention. The ‘practice’ theme revealed that stronger emphasis should be placed on identifying patients at risk and eliminating myths/misconceptions, stressing continued training.

Conclusion

Community health workers can play a significant role in stroke prevention if they are equipped with the needed knowledge, attitudes, and practices. A unique finding is that myths and misconceptions regarding stroke exist among community health workers and should be addressed to practise effective stroke prevention.

1. INTRODUCTION

Stroke remains a significant global health concern and is the second leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide [1]. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that over 15 million people experience a stroke annually, 5 million succumb to it and another 5 million are left permanently disabled [2].

Stroke prevalence in South Africa (SA) has also increased [3], which reflects the ever-growing burden of cardiovascular disease (CVD) in the country. It is well known that individuals with CVD have an increased risk of stroke because of the interconnected risk factors, which include hypertension, diabetes mellites, hyperlipidemia and lifestyle factors [4]. Cardiovascular disease contributes to the overall health burden in SA [5], which accounts for a significant number of non-communicable disease (NCD) morbidity and mortality in the country. Stroke, as one of the major consequences of unmanaged CVD [6], poses unique challenges, especially in regions where healthcare services and resources are limited and populations have decreased access to healthcare. Community health workers (CHWs) play an integral part in SA’s healthcare system, bridging the gap between the healthcare centres and the communities, especially in rural areas [7]. Community health workers deliver essential services such as health education, chronic disease monitoring and screening and work closely with the healthcare professionals (HCPs) in the clinics [8]. While their role in CVD prevention and management is acknowledged [9], a lack of information exists on their specific contributions to stroke prevention, with specific reference to their knowledge, attitudes and practices.

Effective stroke prevention strategies are needed to reduce mortality and morbidity and enhance patients’ quality of life [10]. At a community level, CHWs and HCPs serve as drivers in the primary health care (PHC) field and are essential in prevention strategies [11]. Community health workers and HCPs play a pivotal role in managing known CVD patients and patients at risk of CVD through health education, monitoring and medicinal management [12]. They should be able to identify, educate and manage patients at risk of stroke effectively [12], which largely depends on their level of knowledge, attitudes and practices with regard to stroke prevention [13]. This research focuses on CHWs and HCPs working at community health centres (CHCs) in the North-West Province (NWP) in SA, which has unique healthcare challenges, is resource-limited and has an increased prevalence of CVD [14].

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Study Aim

This research explored CHWs and HCPs’ knowledge, attitudes and practices with regard to stroke prevention with the overarching aim of developing a stroke prevention programme centred on CHWs.

2.2. Study Design

This study followed a qualitative approach, using an exploratory and descriptive design that is contextual in nature [15]. This research design was found appropriate as it enabled us to create a detailed picture and understanding of the CHWs and HCPs’ knowledge, attitudes and practices with regard to stroke prevention. The contextual design facilitated the author collecting data from the CHWs and the HCPs through World Café sessions and focused group discussions (FGDs), respectively, at their place of work, which guided the data collection process. A descriptive design was also followed in both the World Café sessions and FGDs to facilitate in-depth exploration of the prevalence and characteristics of stroke prevention amongst the population.

2.3. Study Setting

The study was conducted in the Dr Kenneth Kaunda district in the NWP and was purposefully selected due to the high prevalence of CVDs and incidences of stroke. The NWP is also one of the first provinces that adopted the Ward-Based Outreach Team Strategy (WBOTS) and is regarded as the province that made significant and sustained progress in terms of PHC outreach teams [16]. The Dr Kenneth Kaunda district consists of three subdistricts, namely Matlosana, Maquassi Hills and JB Marks. The sampling sites comprised all the CHCs in the subdistricts mentioned. Community health centres were purposefully chosen owing to the increased catchment population they serve. Eight CHCs in total were selected for this study.

2.4. Population and Sampling

2.4.1. Population

The target population included CHWs and HCPs working at a CHC in the Dr Kenneth Kaunda district. There are approximately 145 CHWs employed in the Dr Kenneth Kaunda district database. Healthcare professionals serve as an umbrella term in this study, which includes professional nurses (PNs), doctors, dieticians, and physiotherapists working at the CHCs. Determining the exact number of HCPs in the subdistrict is challenging; however, their numbers exceed those of the CHWs and are sufficient to meet the research study objectives.

2.4.2. Sampling

Community health workers and HCPs were purposefully selected and all-inclusive sampling was applied [17]. A total of 90 CHWs participated in the World Café sessions and 49 HCPs in the FGDs.

2.5. Potential Harm and Benefits of the Study

The authors conformed to the principle of distributive justice by ensuring a balance of risks and benefits in the study [18]. The study did not have a direct benefit on the participants but allowed for an opportunity to share their knowledge which could be used to develop a stroke prevention programme. Indirect benefits included CHWs, HCPs and the community’s increased cognisance of stroke prevention, awareness and risk factors. Participants’ identifiers were not revealed, and code names were used during data collection to ensure confidentiality and privacy. Each participant chose their own unique code name. Consequently, all answers cannot be linked to a specific participant or CHC. There were, therefore, no physical or psychological risks associated with participation in this study.

2.6. Informed Consent

Pamphlets and posters that explained the purpose and benefits of the study were distributed at the CHCs as recruitment material. The authors made use of an independent person when informed consent was obtained. The independent person provided and explained the consent forms in English, Afrikaans or Setswana to the potential participants (CHWs and HCPs). The potential participants were reminded that they could withdraw from the study at any time without any repercussions. Participants were reminded that the data gathered during the FGDs and the World Café sessions would be published in accredited journals or presented at national/ international conferences. However, the participants would not be exposed as the information would not be linked to them. The potential participants were allowed sufficient time to ask questions if they had uncertainties, after which they signed the consent forms. A total of 90 CHWs consented to participate in the World Café sessions and 49 HCPs in the FGDs.

2.7. Data Collection Method and Procedure

Data was collected in two phases during this study by the main author during May and June in 2024. In the first phase, the author collected data from the CHWs at the CHCs through World Café sessions. Participants received a standard demographic questionnaire form to complete, which included gender, age, race, home language and level of education. Table 1 provides a summary of the demographic characteristics of the CHWs and the HCPs. The World Café sessions continued with a research assistant explaining the aim of the day and the World Café questions in the participants’ native language. Participants were afterwards randomly allocated to one of five discussion tables, each with a different question regarding stroke. Two tables were allocated to determine the CHWs’ knowledge of stroke, two tables were allocated to determine their attitude, and one table was allocated to determine their current practices with regards to stroke prevention. Participants took part in five rounds of 10–15 minutes each. After each round was completed, the participants were allocated to the next table where another question was discussed. Each table had a table host who remained seated during the rounds. The table hosts represented one of the CHWs who were trained to be able to do the hosting duties. The host introduced the question, summarised previous groups’ thoughts and opinions and made new notes on paper. If the group agreed with an opinion already mentioned on the paper, the host made an asterisk (*) next to the answer. The World Café sessions were also recorded to ensure that no misunderstandings take place during data analysis. After completion of all the tables, the author asked two questions to the participants in the form of a focus group, which aimed at what should be included in a stroke prevention programme centred on CHWs. Table 2 for a summary of data collection questions.

|

CHWs (n = 90) World Café Sessions |

HCPs (n = 49) FGDs |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Gender | ||

| Male | 6 | Male | 7 |

| Female | 84 | Female | 42 |

| Age | Age | ||

| 18–29 | 1 | 18–29 | 10 |

| 30–39 | 21 | 30–39 | 12 |

| 40–49 | 43 | 40–49 | 17 |

| 50–59 | 24 | 50–59 | 8 |

| >60 | 1 | >60 | 2 |

| Race | Race | ||

| African | 87 | African | 46 |

| White | 0 | White | 1 |

| Indian | 0 | Indian | 0 |

| Coloured | 3 | Coloured | 2 |

| Other | 0 | Other | 0 |

| Home language | Home language | ||

| English | 7 | English | 3 |

| Afrikaans | 1 | Afrikaans | 2 |

| Setswana | 67 | Setswana | 29 |

| IsiXhosa | 7 | IsiXhosa | 2 |

| IsiZulu | 0 | IsiZulu | 2 |

| Sesotho | 8 | Sesotho | 6 |

| Tsivenda | 0 | Tsivenda | 6 |

| Xitsonga | 0 | Xitsonga | 1 |

| Level of education | Level of education | ||

| ≤Gr 8 | 1 | ≤Gr 8 | 0 |

| Gr 9–Gr 12 | 89 | Gr–Gr 12 | 0 |

| > Gr 12 | 0 | > Gr 12 | 49 |

| CHWs (World Café sessions) | HCPs (FGDs) | KAP | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Question 1 | What do you know about stroke? | Is stroke a health concern in the community you serve? | Knowledge |

| Question 2 | How do you prevent a stroke? | What skills should CHWs have to help prevent strokes in the community? | |

| Question 3 | What factors enable you to practise stroke prevention? | Describe the ideal attitude a CHW should display towards stroke prevention? | Attitudes |

| Question 4 | What factors hinder you from practising stroke prevention? | How do CHWs currently assist you with regards to stroke prevention? | |

| Question 5 | How do you currently manage patients at risk of stroke? | How could strokes be prevented by the CHWs in the community? | Practices |

In the second phase, the author collected data from the HCPs using semi-structured FGDs. This was chosen as the author aimed to obtain the perceptions, ideas, feelings and shared experiences of the HCPs with regards to stroke prevention strategies with CHWs as catalysts [19]. This allowed the author to understand how the HCPs experience a specific issue and added richness from the diversity of the group dynamics and the discussion regarding the required knowledge, attitudes and practices CHWs need for a stroke prevention programme to be successful [20]. The author envisaged that each FGD should comprise between 6–8 participants. This, however, was not possible at all the CHCs because of staff shortages. The HCPs also received a standard demographic questionnaire form to complete as mentioned above (Table 1 shows for a summary of the HCPs’ demographic characteristics). The FGD lasted between 30–45 minutes. Using semi-structured narrative guides, the author asked five questions (Table 2) to the HCPs in line with the study objective.

2.8. Data Analysis

Analysis of the World Café sessions and field notes was guided by open coding through content analysis, as discussed by Creswell [21]. The two audio recorded questions were transcribed and organised for analysis. The main purpose of open coding was to allow research findings to emerge from repeated, dominant or significant themes from the raw data [21]. The author recruited and made use of an independent co-coder who is regarded as an expert in qualitative data analysis. The author and the co-coder manually analysed the data independently and arranged a meeting afterwards whereby consensus was arrived at with themes, categories and codes that emerged from the data.

Analysis of the FGDs was guided by thematic analysis as proposed by Braun and Clarke [22]. The FGDs were also transcribed and organised for the analysis. This was conducted to identify from the HCPs the expected outcomes and CHWs need to reach the outcomes for a stroke prevention programme. The author used the same co-coder as mentioned above and followed the same process of independent co-coding, finalised by a consensus meeting (Figs. 1 and 2).

2.9. Trustworthiness of the Study Findings

The quality of the findings was ensured by using inductive logic [23], strengthened by the principles of trustworthiness by Guba and Lincoln’s criteria cited in Botma [19]. Confidence in the truth of the findings was established [24] as the author spent adequate time with the participants. Participants were asked to verify the data collected, and continuous observation of verbal and non-verbal communication occurred. This ensured that the author linked the findings with reality [25]. Transferability was ensured as the author used thick description to reach external validity by including satisfactory details when describing the phenomenon and data were collected until data saturation occurred [24]. The findings were formed by the participants and not through author bias (principle of conformability [24], as the findings were grounded by the data obtained and actual events. The author used multiple data sources for an integration of the findings combined with existing literature. To ensure dependability, the author used an independent co-coder, during data analysis, who also did consistency checks [24].

3. RESULTS

The findings are presented under two different objectives. The first objective explored and described CHWs’ knowledge, attitudes and practices toward stroke prevention for individuals at risk of CVD, whereas the second objective explored and described HCPs’ perceptions of the knowledge, attitudes and practices CHWs should have to prevent strokes in individuals at risk of CVD.

3.1. Community Health Workers’ World Café Session Results

A total of 90 CHWs (n = 90) participated in the World Café sessions. The majority were female (n = 84; 93%) and aged between 40–49 years (n = 43; 48%). Most of the CHWs were African (n = 87; 97%) and spoke Setswana as their home language (n = 67; 74%). Nearly all the CHWs’ level of education was between Grade 9–Grade 12 (n = 89; 99%). No participant refused to participate or drop out of the study.

A total of three main themes and eight subthemes emerged from the World Café sessions, aligned with the research objective of determining the knowledge, attitudes and practices CHWs have with regards to stroke prevention. Discussion of themes, subthemes, and categories for the World Café supported by participants’ quotes to provide deeper insights are presented in Table 3.

3.2. Healthcare Professionals’ FGD Results

A total of 49 HCPs (n = 49) participated in the FGDs. The majority were female (n = 42; 86%) and aged between 40–49 (n = 17; 35%). Most of the HCPs were African (n = 46; 94%) and spoke Setswana as a first language (n = 29; 59%).

Themes, subthemes and categories of CHW World Café sessions.

Themes, categories and codes of HCPs FGDs.

The aim of the FGDs with the HCPs was to explore and describe the perceptions of HCPs regarding the knowledge, attitudes and practices CHWs should display for a stroke prevention programme to be successful. A total of three themes emerged from the data. Discussion of themes, subthemes and categories for FGDs supported by participants’ quotes to provide deeper perspectives are presented in Table 4.

4. DISCUSSION

The findings in this study provided significant insights with regards to the current and needed knowledge, attitudes and practices CHWs should display for a stroke prevention programme to be successful. The discussion section is outlined under the main categories, Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices that were found in the World Café sessions and FGDs.

4.1. Current and Required Knowledge

The current and required knowledge of CHWs with regards to stroke prevention is discussed further below.

4.1.1. CHW Current Knowledge

With regards to knowledge, the World Café sessions identified two subthemes, namely general stroke knowledge and stroke prevention knowledge among the CHWs. The findings of the study proved that the CHWs had some knowledge with regards to stroke, highlighting

| Objective: To explore and describe CHW knowledge, attitudes and practices towards stroke and stroke prevention for individuals at risk of CVD | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Categories, themes, subthemes, participant responses and overview of results | |||

| Category | Themes | Subthemes | Participants’ responses and overview of results |

| 1. Knowledge | 1.1 General stroke knowledge | 1.1.1 Stroke terminology | Participant responses:‘stroke of the brain’ (WC 2) ‘brain attack’ (WC 4, 5) ‘damage to the brain’ (WC 3)Overview: Most of the CHWs demonstrated a basic knowledge of stroke terminology, with the majority agreeing to call it a ‘brain attack’. However, some CHWs were unfamiliar with the correct terminology, suggesting a need for training in the area. |

| 1.1.2 Characteristics of stroke | Participant responses:‘attack some parts of the body’ (WC 1, 3) ‘attacks regardless of age’, (WC 6) ‘attacks during sleep’ (WC 6) ‘attacks both male and female’ (WC 6) ‘severe headaches’ (WC 1) ‘loss of consciousness’ (WC 3) ‘silent killer’ (WC 4) ‘attacks the healthy’ (WC 6) ‘can repeat itself’ (WC 6) Overview: Varying levels of knowledge were demonstrated with regards to stroke characteristics. Many identified that stroke affects only specific parts of the body, referring to paralysis or weakness on a specific side. A significant amount also acknowledged that strokes could occur regardless of age and that a headache usually occurs with a stroke. | ||

| 1.1.3 Causes of stroke | Participant responses:‘high blood pressure’ (WC 1, 6, 7, 8) ‘blood vessels not flowing’ (WC 1, 2, 4, 8) ‘blood / damage in the brain’ (WC 3, 5, 7) ‘lack of oxygen to the brain’ (WC 7) ‘narrow veins’ (WC 5) ‘not taking chronic treatment’ (WC 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7) ‘defaulting treatment’ (WC 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7) ‘hypertension’ (WC 2, 4, 6, 7, 8, ‘diabetes’ / ‘high blood glucose’ (WC 2, 7, 8) ‘unhealthy lifestyle’ (WC 1, 5, 6, 8) ‘stress’(WC 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 8) ‘age’ (WC 5) ‘inherit from family’ (WC 5) Overview: The knowledge of causes of stroke was relatively acknowledged among the CHWs. Hypertension and not adhering to treatment were frequently mentioned as a prominent cause, and factors such as unhealthy habits and lifestyle were mentioned. Some CHWs agreed that physiological factors such as narrow veins and the blood vessels not working anymore could also cause a stroke. | ||

| 1.1.4 Management of stroke | Participant responses:‘seeking medical attention’ (WC 6) ‘call an ambulance’ (WC 6) Overview: Most CHWs were aware of the importance of immediate medical management should a stroke occur, by promptly seeking medical attention, and within their limit as CHWs, to call an ambulance. | ||

| 1.1.5 Post stroke consequences | Participant responses:‘parts of the body not working’, (WC 1, 2) ‘permanent or minor disabilities’ (WC 3, 6, 7) ‘terminal’ / ‘death’ (WC 1, 3, 7) ‘family support’ (WC 6) ‘movement affected’ (WC 1, 7) ‘some parts of the body gets paralysed, hand, leg, mouth’ (WC 1, 2, 7) ‘they can’t do anything for themselves’ (WC 7) Overview: CHWs showed some understanding of consequences after a stroke occurs. Many identified permanent or minor disabilities such as deformities or parts of the body not working. Some highlighted the importance of family support post stroke. The long-term impacts of a stroke, however, were not mentioned such as social isolation or financial loss, suggesting an area for further training or awareness. | ||

| 1.1.6 Myths/misconceptions of stroke | Participant responses:‘wearing tight clothes’ (WC 5) ‘witchcraft’ (WC 4) ‘we give vinegar’ (WC 5) ‘placing Disprin under the tongue’ (WC 5) ‘put a spoon in the mouth’ (WC 5) Overview: Interestingly, a considerable number of CHWs demonstrated misconceptions or myths regarding strokes. Many believed that a stroke could occur by wearing tight fitting clothing or even attributing strokes to witchcraft, most likely because of its acute nature. The prevalence of these myths suggests that these misconceptions remain prevalent within the communities they serve. | ||

| 1.2 Stroke prevention knowledge | 1.2.1 Healthy lifestyle and modifications | Participant responses:‘Exercise regularly’ (WC 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8) ‘healthy weight / lifestyle’ (WC 2, 4, 5) ‘eating healthy food’ (WC 1, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8) ‘reduce salt, oil, spices’ (WC 1, 2, 3, 4, 5) ‘avoid sugar’ (WC 2) ‘avoid junk food’ (WC 1, 2) ‘stop smoking’ (WC 1, 2, 3, 4, 5) ‘stop / limit alcohol’ (WC 1, 3, 5, 6) ‘stop drugs’ (WC 2) ‘lots of water’ (WC 1, 3, 4, 7, 8) Overview: CHWs demonstrated awareness of the role of a healthy lifestyle in stroke prevention. They noted the importance of physical activity, maintaining a balanced diet and avoiding bad habits such as smoking and alcohol abuse | |

| 1.2.2 Medicinal management and adherence | Participant responses:‘adhere to treatment’ (WC 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7) ‘regular blood pressure’ (WC 2, 6) ‘maintain cholesterol’ (WC 6) ‘health screenings’ (WC 3, 8) ‘attend doctor appointments’ / ‘regular check ups’ (WC 1, 3) Overview: The participants also recognised the importance of adhering to their prescribed medication, especially for chronic conditions such as hypertension and diabetes. They reported that consistent use of medication helps prevent complications that could lead to stroke. In addition, the CHWs emphasised the importance of attending clinic appointments and early identification of chronic diseases. | ||

| 1.2.3 Stress management and mental health | Participant responses:‘listen to music’ (WC 2) ‘read’ (WC 7) ‘sharing problems’ (WC 3, 6, 7) ‘sharing experiences’ (WC 6) ‘reverends’ (WC 5) ‘family’ (WC 3, 5) ‘friends’ (WC 3) ‘reduce stress’ (WC 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7) ‘rest’ (WC 4, 5) Overview: The CHWs highlighted the impact of stress and poor mental health as a stroke risk. Strategies that were mentioned included relaxation techniques counselling, promoting mental health by seeking help from friends, families and reverends. | ||

| 1.2.4 Community engagement | Participant responses:‘radios’(WC 6) ‘pamphlets’ (WC 6) ‘health education at schools’ (WC 6) ‘health education to community’ (WC 6, 8) ‘support groups’ (WC 1, 5) ‘vegetable gardens’ (WC 1, 4) Overview: The CHWs also reported the importance of community engagement and resources that can be used in stroke prevention. They noted that information should be shared in spaces like schools on community level, also noting the importance of establishing support groups for patients at risk. The use of media like radios was also noted. | ||

| 2. Attitudes | 2.1 Positive attitude influencers | 2.1.1 Effective communication & patient relationships |

Participant responses:‘good communication’ (WC 1, 3, 7) ‘support from family’ (WC 6) ‘cooperation with patients and family’ (WC 6) ‘respect for each other’ (WC 1, 6) ‘friendly’ (WC 2) ‘patients adhere- job easier’ (WC 3, 4, 6) ‘patients listen’ (WC 6) ‘willing to recover’ (WC 6) ‘able to educate patients’ (WC 1, 3, 6, 8) ‘Seeing patients recover’ (WC 1) ‘confidentiality in household’ (WC 6) Overview: CHWs expressed that maintaining open and effective communication with patients and their families promotes respect and trust, ultimately strengthening their working relationship which in turn positively influences their attitudes toward stroke prevention efforts. |

| 2.1.2 Sufficient resources and equipment |

Participant responses:‘pamphlets’ (WC 6) ‘working blood pressure machines / equipment’ (WC 1, 4, 6, 7, 8) ‘blood glucose machines’ (WC 7, 8) ‘measuring tape’ (WC 7) ‘availability of medication’ (WC 3) ‘able to check blood pressure’ (WC 4, 5) Overview: Access to adequate resources and equipment was identified as a significant factor for shaping a positive attitude. Community health workers noted that having the necessary tools such as educational materials and medical equipment medication enhanced their ability to educate, screen and support their patients. |

||

| 2.1.3 Supportive work environment |

Participant responses:‘refer to OTL if CHW can’t manage’ (WC 2, 5, 7, 8) ‘cooperation in workplace / facility managers’ (WC 1, 7, 8) ‘mentoring’ (WC 1) ‘building trust’ (WC 1, 6) ‘work hand in hand’ (WC 1) ‘staff support’ (WC 1, 3, 5) ‘teamwork / unity’ (WC 6) ‘visiting houses in pairs (safety reasons)’(WC 7) Overview: A supportive work environment, which includes collaboration with colleagues and supervisors, was seen as a motivator for the CHWs. They emphasised that teamwork and support from their supervisors contributed to a positive attitude in patient care. |

||

| 2.1.4 Training and development |

Participant responses:‘trainings’ (WC 1) ‘gain knowledge from workshops’ (WC 3) ‘increased knowledge’ (WC 6) Overview: Community health workers noted that regular training and opportunities for development were critical in maintaining a positive attitude. Community health workers appreciated the value of updated knowledge and skills, which empowered them to participate in stroke prevention effectively. |

||

| 2.2 Negative attitude influencers | 2.2.1 Lack of knowledge, training and information |

Participant responses:‘lack of stroke information’ (WC 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8) ‘lack of training on stroke’ (WC 2, 3, 6, 7, 8) ‘need for in-service training’ (WC 7) ‘outdated training-normal blood pressure’ ‘HIV gets priority’ (WC 3) Overview: CHWs reported that inadequate and limited access to up-to-date information negatively impacted their ability to effectively practise stroke prevention. This lack of knowledge created frustration and a sense of inadequacy in fulfilling their roles specifically in stroke prevention, as other conditions receive priority. |

|

| 2.2.2 Insufficient resources and equipment |

Participant responses:‘not working equipment / BP machines’ (WC 1, 2, 6, 7, 8) ‘lack of blood pressure machines’ (WC 1) ‘no batteries’ (WC 5, 6, 7, 8) ‘out of stock medication’ (WC 1, 3, 6) ‘no paper bags for medication’ (WC 1) Overview: The absence of essential resources and equipment, such as working screening equipment and medication, was frequently mentioned as a barrier. Working without the necessary materials prevented them from practising stroke prevention effectively and contributed to feeling demotivated. |

||

| 2.2.3 Financial and employment challenges |

Participant responses:‘salary too low, no benefits’ (WC 1, 3, 5, 6, 7) ‘cost of living too high’ (WC 6) ‘job insecurity’ (WC 3, 5) ‘permanent employment’ (WC 3) ‘one uniform’ (WC 3, 4, 6) ‘no protective shoes’ (WC 3, 7) ‘uniform don’t fit’(WC 6, 7) ‘no name tags’(4, WC 6) ‘no extra pay’ (WC 7) Overview: Low wages and job insecurity were a major challenge mentioned by all CHWs at the sites. Many raised concerns over the lack of financial recognition for their work and uniform issues which left them feeling undervalued and unsupported. |

||

| 2.2.4 Transport and accessibility issues |

Participant responses:‘lack of transport’ (WC 3, 8) ‘limited access’ (WC 7) ‘bad weather’ (WC 1, 2, 3) ‘dogs’ (WC 5, WC 7) Overview: Limited access to transport and long distances to reach patients in remote areas were reported as significant challenges. Accessibility issues such as bad weather and patients’ dogs often hindered their ability to provide timely education and support which led to low morale. |

||

| 2.2.5 Patient and family related barriers |

Participant responses:‘lack of awareness’ (WC 2, 4) ‘not checking blood pressure’ (WC 5) ‘patients refuse treatment’ (WC 1) ‘not adhering to treatment’ (WC 1, 3, 4, 5, 6) ‘patient relocation- don’t form a bond’ (WC 6) ‘patients giving wrong addresses’ (WC 7) ‘not attending doctor appointments due to transport’ (WC 1) ‘bad patient attitude’ (WC 2, 6, 7) ‘denial’ (WC 1, 6) ‘don’t answer door’ (WC 7) ‘not listening’ (WC 2, 5, 7) ‘not following advice / patients refuse’ (WC 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7) ‘family bad attitude / not supportive’ (WC 1, 5, 8) ‘negative’ ‘informal settlement too big’ (WC 6, 7) ‘poverty’ (WC 1, 5) ‘no food / food parcels’ (WC 1) ‘jobless’ (WC 5) ‘care-free lifestyle’ (WC 1) Overview: Resistance from patients and their families were overwhelmingly reported by the CHWs. This included denial of stroke risk, mistrust of CHWs, and non-adherence to advice. Community health workers reported feeling discouraged when their efforts were not well received or resistance from family members was present. |

||

| 2.2.6 Lack of organisational/managerial support |

Participant responses:‘lack – OTLs’ (WC 6) ‘no support- managers’ (WC 6) ‘not considering our problems’ (WC) ‘lack of supervision’ (WC 6) ‘no encouragement’ (WC 6) ‘laziness’ (WC 1) ‘staff attitude’ (WC 1, 2, 6) ‘bad attitude’ (WC 6) ‘no prayer meetings’ (WC 1) ‘lack of debriefing’ (WC 6) Overview: The CHWs also noted that the poor environment the patients live in also contributed to a negative attitude. Community health workers also expressed their dissatisfaction with the lack of support from their organisations or managers. Poor communication, inadequate supervision, limited acknowledgement for their efforts, and staff attitude acted as factors that prevent them from practising stroke prevention. |

||

| 3. Practices | 3.1 Screening and health monitoring | 3.1.1 Screen for chronic conditions |

Participant responses:‘take vital signs / hypertension’ (WC 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8) ‘weight’ (WC 2) ‘blood glucose’ (WC 6) ‘screen the patient’ (WC 3, 6, 8) Overview: Community health workers reported routinely screening patients for chronic conditions such as hypertension and diabetes. These screenings are conducted during home visits or community outreach programmes to ensure the early identification of at-risk individuals. Regular measurement of vital signs, including blood pressure and blood glucose were reported by the CHWs emphasising the importance in detecting abnormalities that could lead to an increased risk of stroke. |

| 3.1.2 Medication delivery |

Participant responses:‘deliver treatment’ (WC 2, 4, 5, 6, 7) ‘adherence’ (WC 3) Overview: Medication delivery was noted several times as practice, as CHWs deliver medication to patients in especially rural areas. |

||

| 3.1.3 Post stroke care delivery |

Participant responses:‘train to do things on their own’ (WC 6) ‘palliative’ (WC 6) Overview: It was noted that CHWs also play a supportive role in post stroke care delivery, as they attend to patients after a stroke occurred. |

||

| 3.2 Health education and support | 3.2.1 Adherence |

Participant responses:‘emphasise adherence’/’take medication regularly’ (WC 1, 2, 3, 4, 6) ‘take medication for stroke prevention’ (WC 2, 4, 5, 7) Overview: CHWs reported educating patients about the importance of medication adherence to manage their chronic conditions. |

|

| 3.2.2 Exercise and diet |

Participant responses:‘encourage exercise’ (WC 1, 2, 5, 6) ‘healthy weight’ (WC 5) ‘salt’ (WC 1, 3, 6) ‘oil’ (WC 1, 6) ‘healthy food’ (WC 2, 5, 6, 7) ‘ 8 glasses of water or more’ (WC 1, 2, 6) Overview: Another common practice was promoting regular physical activity to their patients. The CHWs also greatly emphasised the importance of maintaining a healthy diet for stroke prevention. |

||

| 3.2.3 Substance abuse |

Participant responses:‘avoid, reduce, stop’ (WC 1) ‘stop using tobacco’ (WC 1, 2, 3, 5, 6) ‘stop drinking alcohol’ (WC 1, 2, 3, 5) Overview: They also noted the need for raising awareness about the dangers of smoking and alcohol abuse. |

||

| 3.2.4 Community awareness |

Participant responses:‘old age homes’ (WC 6) ‘schools’ (WC 6) ‘raise awareness’ (WC 6, 8) ‘health talks’ (WC 5, 6, 8) ‘vegetable gardens’ (WC 6) ‘support groups’ (WC 4, 5, 7) Overview: CHWs reported that a common practice is to deliver health education on community level, especially at schools and old age homes, with the goal of raising awareness of chronic conditions. |

||

| 3.2.5 Reduce stress |

Participant responses:‘stop overthinking’ (WC 2, 3) ‘stop stress / reduce stress’ (WC 3, 4, 5, 6) ‘rest enough’ (WC 2, 5) ‘listen to music’ (WC 2) Overview: Stress management was mentioned in multiple World Café sessions, as they recognised the impact stress has on a patient’s overall health. |

||

| 3.2.6 Patient and family support |

Participant responses:‘not ashamed’ (WC 5) ‘jokes’ (WC 3) ‘feel free’ (WC 3) ‘make comfortable’ (WC 3, 5) ‘give family members health education’ (WC 1, 5, 8) ‘bath, feed, wash clothes’ (WC 5) Overview: Another key practice identified was individualised support to their patients and families. Community health workers noted they tell patients not to be ashamed and make regular jokes with them and their family to build rapport. |

||

| 3.3 Referral and collaboration |

3.3.1 Referral to facilities, members of the multidisciplinary team and reasons |

Participant responses:‘after identification you refer’ (WC 1, 3) ‘clinic’ (WC 2, 3, 4, 6) ‘OTLs’ (WC 1) ‘Refer for social grant / SASSA’ (WC 1, 5, 6) ‘physiotherapy /psychology’ (WC 4, 6, 8) ‘patients not adhering’ (WC 6) ‘abnormal vital signs’ (WC 2, 7, 8) Overview: A common CHW practice noted was referral of patients to facilities or to other members of the multidisciplinary team. Community health workers included reasons for usual referral as patients that do not have an income, in need of social support and abnormal vital signs. |

|

| 3.4 Misconceptions / myths |

3.4.1 CHW misconceptions/myths |

Participant responses:‘wear loose socks’ (WC 3) ‘don’t stand on affected side’ (WC 3) ‘massage affected area with vinegar’ (WC 5) ‘put a spoon in patients’ mouth’ (WC 5) ‘should not sleep all day, causes bed sores’ (WC 8) Overview: Interestingly, common stroke myths/misconceptions were found in the practices of CHWs towards stroke prevention. A lot of CHWs reported that a common practice is to advise patients to wear loose socks to prevent a stroke. Also, should a stroke occur, it is a common practice to massage the affected areas with vinegar and put a spoon in the patients’ mouth. |

|

| Objective: To explore and describe the perceptions of HCPs regarding the knowledge, attitudes and practices CHWs should display for a stroke prevention programme | ||

|---|---|---|

| Categories, themes, participant responses and overview of results | ||

| Category | Themes | Participants’ responses and overview of results |

| 1. Knowledge | 1.1 Types of strokes | Participants’ responses:‘I agree and also, to know the types of a stroke, the signs and symptoms of stroke so they can teach the community’. (Code name: Lesedi, FGD 2) ‘Uhm, Mr. Green, yes, I think they should be able to take blood pressures correctly for the hypertension clients and they should know the types of stroke, so that they will be able to diagnose them’. (Code name: Mr. Green, FGD 7) Overview: HCPs emphasised that CHWs should understand the different types of strokes as it is deemed essential for identifying and explaining the condition to the community. Also, recognising the early signs and symptoms to educating the community was deemed essential. |

| 1.2 Causes of stroke | Participant’s response:‘To add on that, they also need knowledge of things that can also cause stroke cause, they shouldn’t just have knowledge of just the elevated BP’s because there's also the obesity. There's also smoking. So, things like that, they should know which age group from this age to that age. This is what is happening so that when they go to patient, patients outside, they are able to educate them about the risk of having stroke with addition on saying this is because of maybe we are smoking. We are taking alcohol. We are doing this. So, in order to prevent getting that stroke, let's reduce on this and this and that. Say no, stop doing this, but in an acceptable way, maybe giving that health education can also assist’. (Code name: Thato, FGD 3)Overview: HCPs emphasised that CHWs should be knowledgeable on the different causes of stroke, and not just focus on elevated blood pressure. If CHWs know what the different causes of stroke are, they would be able to educate their patients more effectively. | |

| 1.3 Risk factors of stroke | Participant’s response:‘The conditions, the risk factors, like age, is the patient smoking. Things related to lifestyle. When they monitor the BP they should write it so we can see the pattern cause at some point the patient will come after 6 months, akere, like I said before then the BP is like elevated at that time and you haven’t seen the patient for a very long time’. (Code name: Atlegang, FGD 3)Overview: It was also expected that CHWs should be knowledgeable about the underlying causes and risk factors of stroke with the aim of raising awareness in the community. This knowledge, the HCPs believed, would enable the CHWs to identify the at-risk individuals and provide stroke prevention health education | |

| 1.4 Signs and symptoms of stroke | Participants’ responses:‘I’m Kea. I want to say the clinical manifestations you know, how can you identify, the signs and the symptoms. How is the patient feeling when they don’t have a BP machine to say this might be 1,2,3’. (Code name: Kea, FGD 4) ‘They should be able to identify the signs of stroke. I think also to monitor the vital signs. Be able to work with a Dinamap’. (Code name: Mrs. X, FGD 2) ‘I firstly think that they need to understand exactly what is a stroke, what causes a stroke, what is the signs of it and how can it be prevented. Those are the critical skills that they need to have you know. Because in order to inform our patients, you need to know, because if they ask questions, you need to understand that you know, this is what a stroke is. This is how you see the signs. These are the early signs. This is how you can prevent it. This is how you can manage it at the time. Ja’. (Code name: Purple Ice, FGD 5)Overview: Healthcare professionals expressed that CHWs should have the knowledge on identifying common signs and symptoms of stroke. This will enable them to identify a stroke if it occurs when they do home visits, and to be able to give correct health education to their patients. | |

| 1.5 Stroke prevention | Participants’ responses:‘Okay, um, I think one on one stroke prevention health education to the patients is important and also having, um, we do host campaigns, the community campaigns, whereby we expect a lot of people’. (Mr. Apple, FGD 6) ‘Knowledge about many things. Um, what is stroke, how to prevent it, what to do, what causes it, the complications, I think’. (Code name: Purple Ice, FGD 5) ‘Yes, they should focus on prevention. It will help them. Focus on the prevention of stroke. Exactly like Mrs. Purple and Mr. Apple said. This should be entertwined. What does stroke mean, how do you define stroke, the signs and symptoms, real life situation. Just add a little bit with regards to prevention, they should focus on stroke prevention’. (Code name: Mrs. S, FGD 6)Overview: Healthcare professionals highlighted on numerous occasions the importance of CHWs having the necessary knowledge with regards to stroke prevention strategies. | |

| 1.6 Management of stroke | Participant’s response:‘Also try to emphasise the importance of treatment and the importance of lifestyle modification and also educating them on how to manage stroke. And also to show some support for the family and to refer them if they need any assistance like if your husband is the breadwinner and you are taking care of him. There's no income, how could they be assisted, that social development, they can see that they get assistance from social development for grants’. (Code name: Mrs. Pink, FGD 7)Overview: Interestingly, the HCPs also highlighted the importance of basic knowledge with regards to stroke management, which includes the importance of early medical care, rehabilitation and providing support to the stroke survivors and their families. | |

| 2. Attitudes | 2.1 Professionalism | Participants’ responses:‘They must also be professional, because people are talking about their conditions to them. So, they should know their privacy, confidentiality, because imagine you are in bed being helpless and sometimes, I would be wearing a nappy and the next thing everyone will hear I was wearing a nappy and it will end up demoralising you as a person and giving attitude to them. So, confidentiality and privacy and also how they share the information’. (Code name: Mrs. Pink, FGD 8) ‘Yes, and then the confidentiality, they shouldn’t share the information to other people about their patients. The patients must trust them. They must know their patients and have trust amongst each other’. (Code name: Mrs. X, FGD 2)Overview: Community health workers were expected to demonstrate professionalism which included privacy and confidentiality when managing patients. |

| 2.2 Responsibility | Participants’ responses:‘Yes, I think it is also important to be able to be willing to learn or like, have a an open mind regarding what they can learn from you and to be able to respective toward what we ask them to do and like also, if they are stuck where they don’t know, to be willing to ask if they don’t understand if they don’t know rather than just ignoring the issue’. (Mrs. Pink, FGD 8) ‘Also, there’s a reminder to them if there's a follow up visits to remind them to come to the clinic for the visits’. (Code name: Monia, FGD 4)Overview: It was also made clear that CHWs should take ownership and responsibility for their roles in stroke prevention. This included identifying at-risk individuals, following up on patients and ensuring timely referrals. | |

| Participants’ responses:‘Just to add on, I also think in terms of they should not be judgemental, remember they are visiting the, the houses with different people, different cultures, different norms and standards. So what would they have been taught at home, should not be forced on the households they are visiting. It is also a respect thing. They should be respectful. It is different households with different people, the, the, they should respect that. Less judgemental or not judgemental at all. The very person they are looking after is a person in their own right. It may be their own family member. What comes around can go around’. (Code name: Mr. S, FGD 1) ‘I think they should be passionate and persistent as well, yeah, supporting, yeah and consistent’. (Code name: Mrs. S, FGD 2) ‘Somebody who's very caring, because if you don’t care, you will never do the right thing. If you don’t care, you won’t do anything and you need to be hands on, if someone is folding their hands, then what’s the use? You can see something is wrong, but they don’t do anything. They need to be hands on’. (Code name: Purple Ice, FGD 5) ‘Mrs. | ||

| 2.3 Caring and Compassion | X. They must also be empathetic and non-judgemental that will also help them with communication with this patient. Because when you are just empathetic then you just judge less at least advise, give help than just to be saying then it is because of what you did that you are here’. (Code name: Mrs. X, FGD 4)Overview: Compassion with a non-judgemental attitude was deemed essential as CHWs should display empathy and understanding towards their patients. | |

| 2.4 Positivity and kindness | Participants’ responses:‘They should be motivated, otherwise it is not going to work. They should have a positive attitude’. (Code name: Mrs. Brown, FGD 6) ‘I think they should just be kind and calm and they should be patient, patient towards the patients themselves. Um it would be like easier to work with the patients if they are kind and calm’. (Code name: Mrs. Blue, FGD 5) ‘Yes, yes. In terms of that positive and loving attitude like an example he said like must communicate with them like they are your family, like your sister or your mother, but so that you encourage adherence and encourage lifestyle modification so that we can prevent it from leading to stroke, so you don’t shout at the patient, you explain to them in a loving manner’. (Code name: Kea, FGD 4) ‘I agree, they should have positive attitude towards learning about stroke, and to, to, can support it’. (Code name: Mrs. S, FGD 6)Overview: Positivity and kindness in their work was deemed essential coupled with active listening and treating all patients with dignity. | |

| 2.5 Patient support and guidance | Participants’ responses:‘And to add on that, since that we have talked about the attitudes of the CHWs, they can be a cheer leader to the client. You know when you are a cheerleader, understand that the client is waiting for you, alright, that person is coming tomorrow. So, they are looking forward to the visits because now she's looking for someone who's always there support her and sharing information’. (Code name: Mrs. P, FGD 1) ‘Yeah, they should. If they come in the morning they do exercises and take their medication and go home. We have the space to do exercises with them and can then give health education. We need to support them more than that, emotionally. They need to look at the patients as a whole. Because I see other health facilities, they do that’. (Code name: Mr. X, FGD 1) ‘Yes, yes. In terms of that positive and loving attitude like an example he said like must communicate with them like they are your family, like your sister or your mother, but so that you encourage adherence and encourage lifestyle modification so that we can prevent it from leading to stroke, so you don’t shout at the patient, you explain to them in a loving manner’. (Code name: Kea, FGD 4)Overview: Healthcare professionals emphasised that the CHWs should focus on both physical and emotional support towards their patients. This in turn will help guide the patients in making better lifestyle choices and fosters trust. | |

| 2.6 Respectful engagement | Participants’ responses:‘I would say they also need, respect you know, it does not mean because you are sick you are getting no treatment, so the same treatment that you want to get, you should also apply it. So, they have to apply mutual respectfulness, so you know, when you respect someone, at least you have that same ground that we are going somewhere but if you want me to listen to you but you don’t listen to me then there is already the conflict so there won’t be a progress so there should be that respect’. (Code name: Apple, FGD 3) ‘I think someone who is a team player. If you are working with stroke patients, you have to be committed and when you see that the patient is weak, they can also communicate and say the last time I saw this person he was like this and then this patient is getting worse. They need to be empathetic with those patients and driven or passionate about their job’. (Code name: Kelebogile, FGD 8)Overview: Respectful engagement was seen as integral in building rapport and fostering respectful patient engagement. | |

| 3. Practices | 3.1 Patient monitoring and assessment | Participants’ responses:‘They do everything, they even take their blood pressure and if it is not normal, they refer immediately to us, and they phone us, saying there is someone who is coming with hypertension’. (Code name: Mrs. Blue, FGD 5) ‘They go to the households and do the vital signs and identify those elevated BPS and refer them to the clinic’. (Code name: Mrs. X, FGD 2) ‘Usually what they do at our facilities, they do take blood pressures, so also the CHWs are taking the treatment from the facility to the patients’ home, usually they are carrying their school bags, they are having their glucometers before giving the treatment to the patient they usually check the blood pressures. They have their carry books to record um, the blood pressure from the patient. If it is high, they usually call and say I am with a patient, I checked the blood pressure, and the BP is elevated. So usually then, I will be going to the patient, check the patient also, then book the patient for the doctor so the treatment can be increased or adjusted’. (Code name: Mrs. Purple, FGD 7)Overview: HCPs emphasised the importance of CHWs being able to do and interpret a blood pressure measurement accurately. Community health workers should also be able to identify early warning signs of a possible stroke. These practices were deemed crucial by the HCPs for stroke prevention. |

| 3.2 Communication and education skills | Participants’ responses:‘The communication skills ne, remember they need to communicate to, to, to communicate the patients. They must come to the client level, they must not use big terms and what what. They must just use basic English or language to communicate, especially those that are not schooled. They need to get to their level, or when they speak other languages. They must come to that level. It will not help if they speak a different language than the patient. They should be having a skill on, they should be able to speak the language of the community for them to help the community effectively’. (Code name: Mr. Apple, FGD 6) ‘Maybe we should teach and help with treatment and health educations. They must tell the patients why they are there, health education on what is stroke and how to drink treatment the correct way’. (Code name: Mrs. S, FGD 1) ‘They must also give health education to the patient telling them the importance of taking treatment especially the hypertensive treatment’. (Code name: Monia, FGD 4)Overview: Effective communication and giving health education was highlighted as a crucial practice for stroke prevention. Community health workers should be able to engage with patients on their level, preferably speaking in the patients’ own language to effectively convey the seriousness of stroke risks. Health education on adherence and how to properly take treatment was also mentioned as crucial practice. | |

| 3.3 Referral and emergency care | Participant’s response:‘Um, where I was working previously, they used to refer with a referral form that’s within the OTL whenever they see patients that they just go to check their vitals and they notice they're very, very abnormal and take the referral forms, state the BP, even if it is only a social problem, meaning a social worker or psychologist, then they just refer on that form to the facility. So, they, they do need one because it would really help them. It would reduce so many things also’. (Code name: Jeanette, FGD 4)Overview: CHWs were expected to be able to refer patients to the different healthcare services that were needed. This included referrals to the OTLs, to the hospital and included social assistance. Their role in early recognition in emergency cases and facilitating the referral process were seen as crucial practice. | |

| 3.4 Medication and home-based care | Participants’ responses:‘I think currently they help us by treating the patients who are not taking treatment especially hypertension treatment and it might lead to the patients’ ill health so, in that sense they are helping. It seems small, but I feel like it's, it's a very useful because if the patient continues years without taking it, it might lead to something bigger than that and some of them take some of the treatment to the patient for the convenience of the patient because sometimes the patient is working and they can’t come to the clinic every time, so it's very difficult for us from our side to give the patient with uncontrolled hypertension treatments. So you see the CHW comes and I don’t want to say are the middleman so this patient is having uncontrolled hypertension but the CHW can take treatment to the patient and treat the patient and when they are there at home they can take the BP as well’. (Code name: John, FGD 4) ‘They help with prevention. They go to the patients that default or have challenges, they do regular house visits so even in that sense, it’s also a prevention to ensure, to before this happens, take the BPs, they check it and see if there is any challenges’. (Code name: Kea, FGD 4) ‘Adherence, adhere to their treatment so that they can be ok. They need to give health education on adherence, it is important’. (Code name: Mrs. Blue, FGD 5)Overview: An essential and an already known practice of delivering treatment and conducting home visits was seen as an integral part of stroke prevention according to the HCPs. This ensures ongoing patient care, adhering to treatment and provision of support to patients who cannot visit the clinic. | |

different terminology, characteristics, causes, management and post-stroke consequences despite not receiving any specific stroke training. It is well documented that CHWs globally, including Africa and, more specifically, SA, do not formally receive stroke-specific training [26, 27]. Community health worker training commonly focuses on addressing non-communicable diseases such as Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and tuberculosis (TB), including addressing social issues such as teenage pregnancies [28-30]. While these are critical in public health, the lack of training on stroke limits their ability to identify, prevent and manage stroke-related issues in their communities [13, 31, 32]. Consequently, gaps in knowledge were identified regarding certain myths or misconceptions regarding stroke. Myths and misconceptions can hinder effective health education and prevention method efforts within the communities that CHWs serve as proved by a study done on the COVID-19 pandemic [33]. Analysis of data revealed that it is crucial to consider the cultural beliefs, traditions and myths that exist in the communities that CHWs serve [34]. As a representative of the communities, the CHWs often share the same culture, background and beliefs [34, 35]. Combined with a lack of formal training, their understanding and communication of conditions may be influenced by local beliefs which can include myths about the causes and management of conditions like stroke. This is especially true in the SA context, as SA is home to 11 official languages and a diverse collection of cultures, each with unique health related perceptions [36]. This was proven to be true in this study as CHWs attributed stroke to supernatural causes such as witchcraft. As CHWs are often seen as frontline workers [33, 37, 38], it is important to address these cultural nuances and debunk these misconceptions in a stroke prevention programme. It is important to note that CHWs should be empowered with the correct knowledge to provide culturally sensitive, yet correct health education and effectively dispel harmful myths to their communities. During the World Café sessions, the CHWs displayed some knowledge regarding stroke prevention specific strategies, highlighting the importance of healthy lifestyle and lifestyle modifications such as alcohol and smoking cessation, the need for regular physical activity and managing their chronic conditions. This links with existing literature that proves that CHWs can play a critical role in advocating behaviour change, emphasising the importance of maintaining a healthy diet, regular exercise and adherence to chronic medication [35, 39-42]. The CHWs consistently indicated that adherence to medication and taking medication as prescribed is needed to prevent strokes. In addition, managing stress and maintaining good mental health was seen as essential in stroke prevention. This finding correlates with a recent West African study proving that chronic stress can attribute to triggering a hemorrhagic stroke event [43], highlighting the importance stress and mental health can play in stroke prevention. This stresses the practical, community orientated approach of CHWs’ daily activities, which can play a key role in fostering preventive behaviours in patients at risk of stroke, if such approach consists of the needed knowledge to do so.

4.1.2. Required CHW Knowledge

Interestingly, the HCPs demonstrated a more specialised and clinically orientated approach regarding the knowledge CHWs should have regarding stroke. Healthcare professionals highlighted that the CHWs should not only know what a stroke is but also have knowledge about the types of strokes that can occur. Similarly, the HCPs indicated that CHWs should have the needed knowledge regarding the causes of stroke and characteristics of stroke. Healthcare professionals felt strongly that the CHWs should be knowledgeable about the signs and symptoms of stroke, as knowing this will enable early recognition and prompt management. Literature supports this finding; this knowledge is essential and allows the CHWs to make earlier referrals, enabling timely treatment, which in turn leads to improved health outcomes [44, 45]. Although not the aim of this study, both the CHWs and HCPs indicated the need for CHWs to have basic knowledge of the management of stroke, linking to the abovementioned of earlier referral and treatment. The findings of this study suggest that while CHWs have some foundational knowledge of stroke and stroke prevention, areas exist that require improvement to strengthen their ability to educate and support their communities more effectively with regards to stroke prevention.

4.2. Current and Required Attitudes

The current and required attitudes of CHWs with regards to stroke prevention are discussed further below.

4.2.1. Current CHW Attitudes

The findings of this study highlighted the complex relationship of factors that influence CHWs’ attitudes towards stroke prevention, as well as the ideal attitudes that HCPs believe CHWs should display in their role in stroke prevention. From the World Café sessions, two distinct subthemes emerged as positive attitude influencers and negative attitude influencers. Positive attitude influencers included factors such as effective communication and patient relationships, access to adequate resources and equipment, supportive work environments and opportunities for training and professional development. Effective communication between the CHWs and their patients was deemed crucial as it builds trust between them, ensuring effective buy-in when giving health advice, as proved by a study conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic [46]. Community health workers also reported in this study that if they had the necessary working equipment, like an automated blood pressure monitor, they could practise stroke prevention more effectively. It is well documented that CHWs could be more effective in their roles when they have access to adequate working equipment [47]. Tools such as blood pressure monitors, glucose meters and educational material are essential to perform their tasks more efficiently [48]. This however, as discussed, was only found at one data collection site, as working equipment remains a challenge in a resource stricken country such as SA [49]. The findings also proved that CHWs who work in a supportive environment were more committed to practising stroke prevention. Research corroborates this finding, which also states that when CHWs operate in a supportive work environment, they are more likely to go beyond their standard responsibilities and take on additional tasks such as stroke prevention [50, 51]. Some CHWs mentioned during the World Café sessions that opportunities for training and professional development were seen as a positive influencer towards stroke prevention. However, CHWs do not receive standard stroke prevention training; they expressed their interest in learning more about stroke prevention and recognised the increased knowledge as motivation to practise stroke prevention more adequately. Conversely, negative attitude influencers emerged from the data, such as a lack of knowledge and training and information on stroke. Community health workers expressed a dire need for more information with regards to stroke, as training on the subject is scanty and a lack of information exists, which demotivates them in practising stroke prevention. As found by a study by Johnson et al. [52], CHWs are more motivated to perform tasks if they are well trained and have sufficient knowledge related to the task. As previously mentioned, stroke prevention does not get preference in CHW training, as other conditions are prioritised, such as HIV and TB, which hinders CHWs from practising stroke prevention [53]. Limited resources were found prevalent at most of the data collection sites, with CHWs citing no batteries, no blood pressure monitors or even simple equipment such as a scale and measuring tape as barriers to practising stroke prevention. South Africa, known as a low-middle-income country (LMIC), faces significant financial constraints that affect various sectors, including the healthcare sector, which were well documented during the COVID-19 pandemic [54, 55].These economic challenges often affect primary healthcare services, which directly affect the resources available to CHWs. This lack of resources limits their motivation and ability to effectively practise stroke prevention in their communities, ultimately hindering efforts to reduce the burden of stroke. Financial constraints and employment challenges were highlighted as negative attitude influencers by the CHWs in this study. It is well known that CHWs work under precarious conditions, receiving low wages and often lacking formal employment benefits such as job security or career progression opportunities [56, 57]. Community health workers reported that they were reluctant to engage in additional responsibilities such as stroke prevention owing to inadequate compensation and a lack of motivation. Community health workers felt undervalued and overburdened [58], as their scanty remuneration does not reflect the role they play in community healthcare [58]. This lack of financial support can lead to decreased enthusiasm to partake in additional responsibilities such as stroke prevention. Lack of transportation and accessibility issues significantly hindered CHWs from practising stroke prevention in this study. It is well documented that CHWs are required to walk far distances to reach their patients, and some report that they are not receiving adequate footwear or uniforms while experiencing challenging weather conditions, which discourage their efforts [59, 60]. Additional barriers such as the patients’ pets, in particular dogs, can prevent CHWs gaining access to their patients’ households, further limiting their stroke prevention efforts. Community health workers reported that patients and their family related barriers also influenced their attitude towards stroke prevention. Patients often resist advice and refuse to adopt healthy behaviours [60]. Furthermore, families can be unsupportive with some being rude or even dismissive towards the CHWs, failing to assist their loved ones in making the necessary lifestyle changes. This lack of cooperation undermines the effectiveness of CHWs in their efforts [61]. A lack of organisational support also served as a negative attitude influencer towards stroke prevention. Outreach team leaders (OTLs) often fail to provide adequate guidance, are frequently unavailable and do not offer the supervision needed to address the challenges faced by CHWs, which is essential for good CHW work performance [62, 63]. In addition, negative clinic staff attitude further demotivated CHWs in practising stroke prevention as they felt undervalued and unsupported in their efforts.

4.2.2. Required CHW Attitudes

Conversely, the FGDs with the HCPs emphasised the ideal attitudes CHWs should display towards stroke prevention. The subthemes included professionalism, responsibility, caring and compassion, positivity and kindness, patient support and guidance and respectful engagement. The HCPs noted that these attitudes are essential to building rapport and trust, which foster effective communication and encourage behaviour change in patients. Importantly, HCPs emphasised that a positive and compassionate approach not only supports patient adherence but also reflects the CHWs’ commitment to their critical role in community-based care. The importance of following a compassionate approach is well documented [64-66]. The alignment between the perspectives of CHWs and HCPs underscores the importance of addressing systemic challenges that negatively influence CHWs’ attitudes. While CHWs have a clear understanding of the importance of effective patient relationships and a supportive work environment, the lack of resources, training and managerial support diminishes their ability to maintain an ideal attitude towards stroke prevention. This is particularly relevant in resource limited settings such as the NWP, where CHWs often work under challenging conditions. Strengthening their support systems, providing adequate resources and offering continuous training can enhance CHWs’ attitudes [35] and align them more closely with the ideal attributes identified by the HCPs, ultimately improving stroke prevention efforts for at risk CVD patients.

4.3. Current and Required Practices

The current and required practices of CHWs with regards to stroke prevention are discussed further below.

4.3.1. Current CHW Practices

From the World Café sessions, several key practices emerged from the data, including screening and health monitoring, health education and support, referral and collaboration and medication and home-based support. Community health workers reported that part of their daily activities was to deliver medication, screen for chronic conditions and measure vital signs, which is a common practice in literature [67]. These practices are essential for early detection of chronic diseases, prevention of complications and effective disease management [68]. Community health workers are doing their best to prevent strokes effectively; however, their effectiveness in performing tasks like measuring and interpreting blood pressure are hindered by self-acknowledged limited training and insufficient knowledge. Another essential practice CHWs reported was engaging in health education and patient support on a daily basis. Health education ranged from adherence counselling, promoting physical exercise, avoiding substance abuse and reducing stress as these are known risk factors of a stroke [69-71]. In addition, CHWs reported providing family support to their patients, especially in cases where a stroke has already occurred. A lot is known of the benefits of CHW support to patients and their families post stroke [32, 72], and this study proved no different. By encouraging family involvement, CHWs can help foster a supportive environment that may help patients adopt and maintain a healthy lifestyle [73], which in turn can decrease the incidence of stroke. Community health workers reported that referral and collaboration with other members of the multidisciplinary team also formed part of a key practice. Community health workers often refer patients to the clinics or other members of the multidisciplinary team, depending on the reason for the referral. Reasons for referral often include non-adherence, abnormal vital signs or patients that need social assistance because of poverty. The CHWs however, voiced their concerns as the referral process is often difficult, and they do not always have the assistance to do so. Shortage and long waiting times for South African emergency medical services are well documented [74, 75], and they often struggle to do a proper assessment and handover owing to a lack of training in this regard. Interestingly, similar to CHWs’ knowledge, another misconception or myth emerged from the CHWs’ practices. Community health workers reported common practices like massaging the affected areas with vinegar after a stroke, advising patients to wear loose socks to prevent a stroke and putting a spoon in patients’ mouths if they believed they had a stroke. These practices reflect the influence of cultural beliefs and traditional approaches to health that are deeply rooted in their communities and shaped by their educational backgrounds. It can be concluded, since a lack of evidence exists, that this phenomenon, which is unique to the South African context, highlights the intersection of cultural norms and healthcare practices. This emphasises the need for culturally sensitive education to dispel myths and provide best practice stroke prevention strategies.

4.3.2. Required CHW Practices

The HCPs, through the FGDs, highlighted practices they believed CHWs should prioritise to improve stroke prevention. Similarly to the CHWs, HCPs emphasised the importance of patient monitoring and assessment, communication and assessment and referral on collaboration. Both groups recognised the need to identify individuals at risk, providing good education to their patients and communities and performing timely and appropriate referrals. Healthcare professionals, however, felt that CHWs should also expand their role in medication delivery and home-based support. Some HCPs believed that CHWs should be trained to deliver a wider variety of medication, which in turn could help stroke prevention. This was explored in some studies [76, 77] providing promising results. An overwhelming number of HCPs emphasised the need for CHWs to be able to measure blood pressure correctly and interpret the results accurately, as this, in turn, will lead to improved patient outcomes. This corresponds with the CHWs’ self-reported lack of knowledge in this regard and should be kept in mind when developing a stroke prevention programme. The alignment between the CHWs and HCPs regarding the practices underscores the foundational role CHWs can ultimately play in stroke prevention. The persistence of myths/misconceptions in their knowledge and practices; however, highlights the need for ongoing training to align their practices with best evidence guidelines. In addition, the emphasis from HCPs on medication delivery and home-based care points to the need for a broader scope of practice for CHWs, supported by adequate resources, supervision and training.

The study had two main limitations that should be acknowledged. Firstly, the findings of this study are context-specific and qualitative in nature. This implies that the study is not generalisable to broader populations but can be used as a guide for similar contexts. Secondly, the study aimed to include a variety of HCPs, including PNs, doctors, dieticians and physiotherapists. However, participation from other members of the HCPs other than PNs was limited due to their unavailability. Consequently, the sample was mainly comprised of PNs. It is recommended that future research should specifically target each healthcare profession to obtain a comprehensive understanding of their knowledge, attitudes and practices towards stroke prevention [78].

CONCLUSION

The findings of this study emphasise the importance of equipping CHWs with the knowledge, attitudes and practices required for stroke prevention, while addressing cultural influences that may have an impact on their practices. A unique finding proved that myths and misconceptions surrounding stroke prevention significantly influence the knowledge and practices of CHWs. These myths can hinder stroke prevention efforts, underscoring the need for targeted education and awareness initiatives. It is crucial when designing stroke prevention programmes to address and correct these myths to ensure CHWs have accurate information that they convey to their patients and communities. It can also be deduced further that a collaborative approach between the CHWs and the HCPs, supported by adequate resource allocation and targeted training, is essential to optimise stroke prevention efforts in the NWP and similar resource limited settings.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

It is hereby acknowledged that all authors have accepted responsibility for the manuscript's content and consented to its submission. They have meticulously reviewed all results and unanimously approved the final version of the manuscript.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| CHC | = Community Health Centre |

| CHW | = Community Health Worker |

| CHU | = Centre Hospitalier Universitaire |

| COVID-19 | = Coronavirus Disease 2019 |

| CVD | = Cardiovascular Disease |

| DoH | = Department of Health |

| FGD | = Focus Group Discussion |

| HCP | = Health Care Professional |

| HIV | = Human Immunodeficiency Virus |

| HREC | = Health Research Ethics Committee |

| LMIC | = Low-Middle-Income Country |

| MCH | = Maternal and child health |

| NCD | = Non-Communicable Disease |

| NuMIQ | = Quality in Nursing and Midwifery |

| NWP | = North West Province |

| NWU | = North West University |

| OTL | = Outreach Team Leader |

| PHC | = Primary Health Care |

| PNs | = Professional nurses |

| SA | = South Africa |

| TB | = Tuberculosis |

| WBOTS | = Ward-Based Outreach Team Strategy |

| WHO | = World Health Organization |

| WSO | = World Stroke Organization |

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

The author obtained approval from the Quality in Nursing and Midwifery (NuMIQ) scientific committee and the North-West University (NWU) Health Research Ethics Committee (HREC), with ethics number NWU-00003-23-A1. The author also received permission from the North-West Department of Health (DoH).

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of institutional and/or research committee and with the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki, as revised in 2013.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

The author used the forms available from the NWU as a guideline to obtain the consent. Consent was needed from the North-West DoH as the author made use of their facilities and personnel during the data collection phase of the study. Final approval was only granted once approval from the DoH was obtained and the appropriate healthcare facilities had provided their goodwill permission letters.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

The data and supportive information are available within the article.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The manuscript is based on the PhD thesis of Ms. S Botha, a lecturer at the NWU. The authors wish to thank the NWU and the North West DoH for their permission to collect data and all the participants who agreed to participate in the study.