All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Effectiveness of the Health Literacy Promotion Program on Health Behaviors and Health Outcomes among Pre-aging Individuals with Overweight and Obesity

Abstract

Introduction

According to the existing studies, there are relatively few studies about the effectiveness of the health literacy promotion program on health behaviours and health outcomes among pre-aging individuals with overweight and obesity. According to the aforementioned problems and reviewed data, this study aimed to address the need for accessible health knowledge. Particularly, older adults with obesity should aim to lose weight and prevent chronic diseases caused by obesity, thereby preparing them to handle age-related health conditions.

Methods

This study employed a pretest-posttest Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT) conducted between February and June 2024 among pre-aging individuals with overweight and obesity in Thailand. The total sample size was 136 (the control arm had 68 samples, the experimental arm had 68 samples).

Results

The study assessed the health behaviors and outcomes of an older adult group with overweight and obesity, following their participation in a health literacy development program. Post-intervention, the experimental arm exhibited significantly higher health literacy scores (p < 0.001) and health behavior scores related to overweight and obesity (p < 0.001) compared to the control arm. Furthermore, the overall health outcomes of the experimental arm were also significantly better than those of the control arm (p-values ranging from 0.001 to 0.004).

Discussion

This study shows that a health literacy promotion program can significantly improve health behaviors and outcomes in pre-aging individuals with overweight and obesity. Compared to the control arm, participants in the experimental arm received better clinical scores and effectively improved their own health conditions, indicating that the program is conducive to promoting a healthy lifestyle and preparing for aging.

Conclusions

These findings provide evidence to support the health literacy concepts as guidelines for developing a health-promoting program for the pre-aging group with overweight and obesity.

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1. Background/Rationale

The World Health Organization (WHO) indicated that over a billion people around the world are living with obesity. WHO estimated that about 167 million people, including adults and children, will experience deteriorating health by 2025 because of overweight or obesity [1]. Obesity leads to chronic diseases that affect the quality of life. These diseases, in turn, result in substantial economic losses due to increased healthcare costs and contribute to a significant burden of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), which measure years lost due to disability and premature deaths. Obesity causes pain, discomfort, and lowers the quality of life through mental problems such as negative self-perception, low self-esteem, stress, and depression [2]. Being overweight increases the risks of high blood pressure, type 2 diabetes, coronary artery disease, stroke, gallbladder disease, knee osteoarthritis, obstructive sleep apnea, respiratory problems, endometrial cancer, breast cancer, prostate cancer, and colorectal cancer [3].

According to the 6th Thai National Health Examination Survey, conducted from 2018 to 2020, the Thai people aged 15 years or older had an average BMI of 24.7 kg/m2. However, 42.2% of this population met the criteria for obesity (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2). The highest prevalence of obesity was found in the group of people aged 45–59 years (Mean BMI = 25 kg/m2). In contrast, a lower prevalence was observed in the elderly population. The lowest prevalence was found in the group of people who were 80 years or older [4]. The pre-aging population (45-59 years) was a group of people with changing health conditions, as their hormone levels were declining and they were experiencing physical declines. Consequently, their health problems differed from those of other groups [5]. Therefore, preparation for pre-aging was important, and all people had to be aware of and adapt to it [6].

A review of the literature on health literacy revealed that the WHO began focusing on health literacy in 1998, launching campaigns to encourage member countries to provide health knowledge to their populations [7]. Health literacy refers to the cognitive and social skills that determine an individual's motivation and ability to access, understand, and use information in ways that promote and maintain good health [8]. The Department of Health stated that individuals with health literacy possess all six components, as follows: 1) Access to information; 2) Understanding; 3) Interaction, Questioning, and Exchange; 4) Decision-making; 5) Behavior change; and 6) Communication skills [9]. The systematic review by Michou et al. [10] found that inadequate health knowledge was related to increased BMI, overweight, and obesity. The study by Cheng et al. [11] found that people who had physical checkups at Taipei Veterans General Hospital had high BMIs and also demonstrated lower health literacy scores. The study by Erdogdu et al. [12] found that BMI and health literacy were related, as high scores in health literacy were associated with successful weight loss after surgery for treating patients with obesity. The study by Lassetter et al. [13] on native Hawaiian and Pacific islanders in the United States found that low health literacy was associated with higher BMI and older age. Moreover, Lin et al. [14] examined the effects of a community-based participatory health literacy program on health behaviors and health empowerment among community-dwelling older adults in a quasi-experimental study. The findings showed that the group with the intervention had significantly improved health behaviors, including controlling weight, regularly working out, and accessing health information.

According to the existing studies, there are relatively few studies about the effectiveness of the health literacy promotion program on health behaviors and health outcomes among pre-aging individuals who are overweight and obesity. According to the aforementioned problems and the reviewed data, this study aims to address the need for health knowledge among the general population. Particularly, the pre-aging people with obesity should be able to lose weight and prevent chronic diseases caused by obesity in order to prepare them to handle conditions caused by being old people. Additionally, the data from this study should serve as guidelines for conducting activities and developing health promotions, enabling individuals to select practices and adopt behavioral changes that have a positive impact on their health and well-being.

1.2. Purpose of the Study

To study the effectiveness of the health literacy promotion program on the health behaviors and the health outcomes of the pre-aging group with overweight and obesity.

1.3. Research Hypotheses

Following participation in the health literacy promotion program, the experimental arm (comprising older adults with overweight and obesity) demonstrated notable improvements. Specifically, their scores in health literacy and health behaviors related to overweight and obesity were significantly higher than pre-program levels. Furthermore, the overall health outcomes for this group also improved compared to their baseline.

Following participation in the health literacy promotion program, the experimental arm (comprising older adults with overweight and obesity) demonstrated significant improvements compared to the control arm. Specifically, they showed better scores in both health literacy and health behaviors concerning overweight and obesity. Additionally, their overall health outcomes were superior to those of the control arm.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Study Design and Settings

This study employed a baseline and follow-up Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT) design, conducted between February and June 2024, among older adults who are overweight or obese in Thailand.

2.2. Study Sample and Data Collection

This study was conducted by dividing into 2 experimental groups: 1) The control arm that received standard care, and 2) The experimental arm that attended the program. Inclusion criteria are as follows: 1) Overweight and obese pre- aging people with BMI ≥ 23 and are aged 45–59, 2) Be capable of understanding and speaking Thai, 3) Not having a chronic illness that necessitates medicine, such as cancer, AIDS, diabetes, high blood pressure, renal failure, or high blood sugar, and 4) Not a disabled individual. Exclusion criteria are as follows: 1) Suffering from an urgent disease that needs treatment or an acute infection, 2) exhibiting signs of a potentially communicable, severe, contagious illness, and 3) being unable to finish the 12-week course. The criteria determination for termination of participation in the sample study is as follows: 1) The sample groups have to be hospitalized or undergo surgery during the research which prevented them from participating in the planned activities, 2) the sample groups have an accident or injury that prevented them from participating in the planned activities, and 3) the sample groups request to withdraw from the research after participating in the program.

Sampling procedure for the selection of experimental and control groups.

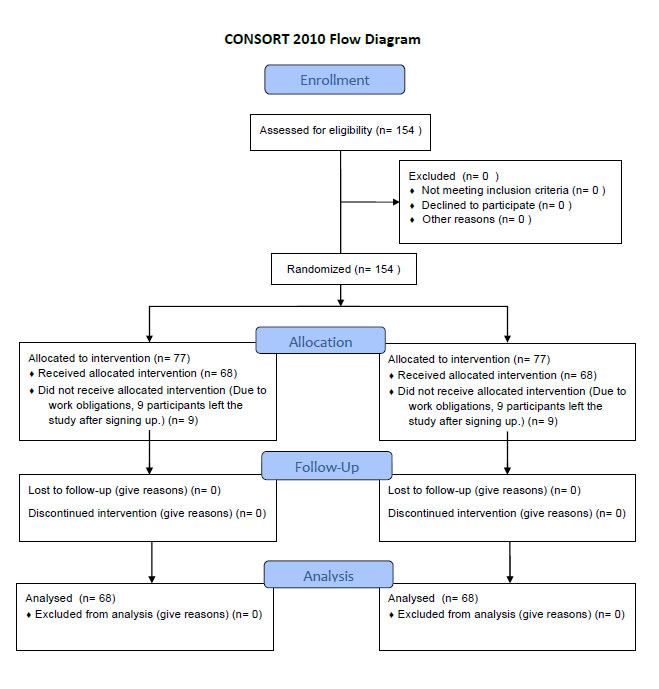

A test was conducted before the program activity, and a post-test was administered 12 weeks after the program concluded. In the 16th week (Intervention: 12 weeks, follow-up at the 16th week), the sample groups consisted of pre-aging individuals (aged 45–59) in Mueang Lamphun District, Lamphun Province, who were overweight and obese (BMI ≥ 23). For this study, the sample size was calculated using G*Power software. A power analysis was conducted for a statistical test of means (difference between two independent means for two groups). The parameters used were a test power of 0.8, a significance level of 0.05, and a medium effect size of 0.5. The sample size had been calculated to consist of 64 subjects in each group. However, to mitigate the effect of participant withdrawal, the researcher increased the sample size by twenty percent. Consequently, the experimental arm consisted of 77 participants, while the control arm also had 77 participants. However, 9 participants from each group had withdrawn from the study after enrolling in the program due to work commitments, leaving 68 subjects in the control arm and 68 in the experimental arm, for a total of 136 subjects. The control arm consists of samples from 5 villages, using cluster randomization. The experimental arm is derived from samples collected in 5 villages, using cluster randomization. Chosen samples for research studies on both the experimental arm and the control arm, using a random village area's selection of names from the population record in accordance with the preliminary inclusion criteria, are shown in Fig. (1).

The sample group is informed about their rights during participation in the research study, which includes the right to confidentiality when sharing or exchanging information. The researcher was study is summarized in the report. The sample group was not mentioned personally, and there were no searchable references for the sample group. Information received from this study will not be disclosed; it will be used for educational benefits only. The information was presented as n overview without specifying the name of the person providing the information. The sample group can leave or cancel the provision of information at any time. If they do not wish to provide further information, the sample group will not lose any benefits at all.

2.3. Instruments and Measurements

2.3.1. Intervention Design

Health Literacy Promotion Program on Health Behaviors and Health Outcomes among Pre-aging Individuals with Overweight and Obesity (Intervention design was created and modified by the researcher from the literature review, with improvement based on advice from 3 experts).

2.3.2. Tools Used in Conducting Research

A number of tools were utilized, including communication, documentation, and participant engagement materials, to assist with the intervention. Health information was presented using tools such as Power Point slides. Key messages and tasks to be completed by participants were included in a series of reminder notes. Forms to record telephone calls also helped track interactions and follow-ups. To increase participant awareness and motivation, letters containing information on healthcare and obesity were issued to subjects in the intervention group. Verbal responses and participant interactions during activities were captured using audio recording devices (voice recorders, mobile phones). Analogously, we used image-recording devices, including digital cameras and mobile phones, to photograph and document the activities and tasks performed by participants. The monitoring system included brief telephone interventions and follow-up calls. In addition, a range of supplementary materials, including but not limited to toys, games, pens, colored paper, flipchart paper, and Post-it Notes, were employed to support engagement and interaction during the program's hands-on and interactive elements.

2.3.3. Data Collection Tools

Variables: demographic characteristics, health literacy, health behavior, BMI, waist circumference, blood pressure, total cholesterol, LDL-cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol, triglyceride, fasting plasma glucose.

- The questionnaire was created and modified by the researcher from the literature review, with improvement based on advice from 3 experts, measuring health literacy and health behavior using the questionnaire comprised three parts: Part 1 – general information; Part 2 – health literacy about overweight and obesity; and Part 3 – health behaviors regarding overweight and obesity. This index of Item-Objective Congruence (IOC) was calculated according to the average of three experts’ congruence scores for each item. An acceptable IOC value was defined as ≥ 0.66. The experts' comments and recommendations were used to modify and improve the questionnaire. Its reliability was assessed using Cronbach's alpha coefficient, which yielded a score of ≥ 0.80, indicating that the questionnaire is suitable for data collection. A pre-test was conducted before the program activity, and the post-test was administered in the 12th week after the program concluded, as well as in the 16th week.

- Assessment of weight, height, waist circumference, and blood pressure: The weight assessment will be carried out using a numeric standing scale with a measurement accuracy of 0.1 kg, and the scale will be standardized against the standard weight. The height assessment is to be conducted with a height measuring device. Meanwhile, waist circumference would be assessed using a tape measure, and blood pressure would also be measured. Blood pressure assessment would be conducted using a machine from the Subdistrict Health Promotion Hospital, which has undergone standard testing. A pre-test was conducted before the program activity, and the post-test was administered in the 12th week after the program concluded, as well as in the 16th week.

- Blood test to check for total cholesterol, LDL-cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol, triglyceride, and fasting plasma glucose: Standard laboratory procedures were followed while obtaining blood from the certified agency. A pre-test was conducted prior to the program activity, and a post-test was administered at follow-up in the 16th week.

2.3.4. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS). Both descriptive and inferential statistics were applied in this study.

- A descriptive statistical analysis of personal factors, health literacy and health behaviors concerning overweight and obesity, and the sample groups’ health outcomes was conducted. Frequencies, percentages, means, standard deviations, maximums, minimums, and medians were used to describe the data

- Inferential statistics were used to measure intervention efficacy. An independent t-test and a Fisher’s exact test were performed to analyze the differences in demographic characteristics between the control and experimental arms. Repeated-measures ANOVA (Analysis of Variance) was conducted to compare within-group health literacy, health behaviors related to overweight and obesity, Body Mass Index (BMI), waist circumference, systolic blood pressure, and diastolic blood pressure across three time points (pre-intervention, week 12, and week 16). For between-group comparisons of these same variables for the defined time points, the Mann-Whitney U test was used. Moreover, the Mann–Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare between experimental and control arms concerning total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL–C), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL–C), triglycerides, and FPG in the pre-intervention and 16th week time points. Statistical analysis was conducted to compare these biochemical markers at baseline and post-intervention using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test within the groups.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Demographic Data of the Participants

The present study included a pretest-posttest RCT of 136 individuals with pre-aging, overweight, or obesity who took part in an experimental intervention program. Participants were randomly allocated into one of two groups: an experimental arm (n = 68) that received a health literacy promotion program targeting health behaviors and outcomes, or a control arm (n = 68) that received standard care.

Regarding gender, most participants were female in both the experimental arm (75.00%) and the control arm (64.71%). The mean age of participants in the experimental arm was 53.75 years (SD = 3.85), with nearly half (47.06%) of them in the 55–59 year age range. The control arm mean age was 53.46±3.98 years (44.12% in this age range).

Table 1 shows that the majority of participants in both groups had a primary school education or lower (69.12% for the experimental arm and 57.36% for the control arm). Concerning matrimonial status, the maximum percentage of the study sample in both groups was living with their spouses (75.00% & 76.47%, respectively).

Most participants from the experimental arm worked as general contractors (45.59%), while the leading occupation for participants in the control arm was agricultural and farming work, including gardening (35.29%). Regarding monthly income, most people in both groups earned an income not exceeding 10,000 baht/month (75.00% in the experimental arm, 73.53% in the control arm). The mean monthly income of the experimental and control arms was 9,855.88 baht (SD = 6,990.32) and 9,773.53 baht (SD = 6,276.79), respectively.

Differences in demographic characteristics between control and experimental arms were examined using independent t-tests and Fisher’s Exact tests. There were no statistically significant differences, confirming that the 2 groups were similar regarding demographic variables.

3.2. Comparisons of Health Literacy, Health Behaviors about Obesity Scores, and the first health outcomes between the Control and the Experimental Arms at Each Point of Measurement

Multiple pairwise comparisons were performed between each measurement point using the Bonferroni test. In the experimental arm, significant differences in total health literacy scores related to obesity were observed between the pre-test (baseline) (Median = 98.00, IQR = 12) and the post-test at 12 weeks (program completion) (Median = 125.50, IQR = 20), between the pre-test and the post-test at 16 weeks (follow-up) (Median = 133.00, IQR = 10), and between the post-tests at 12 and 16 weeks. In contrast, the control arm showed no significant differences in total health literacy scores between any of the measurement points: pre-test (Median = 102.50, IQR = 24), post-test at 12 weeks (Median = 103.50, IQR = 27), and post-test at 16 weeks (Median = 103.50, IQR = 23), as shown in Table 2.

Multiple pairwise comparisons were performed using the Bonferroni test. In the experimental arm, significant differences in total health behavior scores related to obesity were observed between the pre-test (baseline) and the post-test.(Median = 52, IQR = 7) and post-test at 12 weeks (program ended) (Median = 65, IQR = 8), between pre-test (baseline) and post-test at 16 weeks (follow-up) (Median = 65, IQR = 3), and between the post-tests at 12 and 16 weeks. In contrast, the control arm showed no significant differences in total health behaviors scores between any of the measurement points: pre-test (Median = 51, IQR = 7), post-test at 12 weeks (Median = 51, IQR = 6), and post-test at 16 weeks (Median = 50, IQR = 4), as shown in Table 2.

Table 1.

|

Demographic Characteristics |

Control (n = 68) | Experimental (n = 68) | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |||

| Gender | 0.241 | |||||

| - Male | 24 | 35.29 | 17 | 25.00 | ||

| - Female | 44 | 64.71 | 51 | 75.00 | ||

| Age (years) | 0.187 | |||||

| Min - Max | (45 - 59) | (45 - 59) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 53.46 (3.98) | 53.75 (3.85) | ||||

| - 45 – 49 - 50 – 54 - 55 – 59 |

14 24 30 |

20.59 35.29 44.12 |

8 28 32 |

11.76 41.18 47.06 |

||

| Education Level | 0.807 | |||||

| - Primary school and lower | 39 | 57.36 | 47 | 69.12 | ||

| - Secondary school | 17 | 25.00 | 12 | 17.65 | ||

| - Diploma | 7 | 10.29 | 7 | 10.29 | ||

| - Graduate and above | 5 | 7.35 | 2 | 2.94 | ||

| Marital Status | 0.754 | |||||

| - Single | 7 | 10.29 | 6 | 8.82 | ||

| - Lived with their spouse | 52 | 76.47 | 51 | 75.00 | ||

| - Separated from their spouses | 4 | 5.88 | 4 | 5.88 | ||

| - Widowed/ Divorced | ||||||

| Occupational Status | 0.398 | |||||

| - Agriculture | 24 | 35.29 | 11 | 16.18 | ||

| - Merchant/ Self-employed | 20 | 29.41 | 14 | 20.59 | ||

| - Government service / Factory worker / Private sector employee | 4 | 5.88 | 12 | 17.65 | ||

| - General contractor | 20 | 29.41 | 31 | 45.59 | ||

| Monthly Income (Baht/Month) | 0.847 | |||||

| Min - Max | (3,000 - 35,000) | (3,000 - 45,000) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 9,773.53 (6276.79) | 9,855.88 (6990.32) | ||||

| - ≤ 10,000 | 50 | 73.53 | 51 | 75.00 | ||

| - 10,001 – 20,000 | 15 | 22.06 | 13 | 19.12 | ||

| - 20,001 – 30,000 | 2 | 2.94 | 3 | 4.41 | ||

| - ≥ 30,001 | 1 | 1.47 | 1 | 1.47 | ||

| Comparison Median |

Pre-test (Baseline) |

Post-test at 12 weeks (Program ended) |

Post-test at 16 weeks (follow-up) |

p-value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

(1) Median (IQR) |

(2) Median (IQR) |

(3) Median (IQR) |

(1) VS (2) | (1) VS (3) | (2) VS (3) | ||||

| Total Health Literacy | |||||||||

| Control arm |

102.50 (24) |

103.50 (27) |

103.50 (23) |

0.559 | 0.108 | 1.000 | |||

| Experimental arm | 98.00 (12) |

125.50 (20) |

133.00 (10) |

< 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |||

| Total Health Behaviors | |||||||||

| Control arm |

51.00 (7) |

51.00 (6) |

50.00 (4) |

1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | |||

| Experimental arm | 52.00 (7) |

65.00 (8) |

65.00 (3) |

< 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |||

| Body Mass Index | |||||||||

| Control arm |

25.37 (2.91) |

25.31 (3.23) |

25.10 (3.19) |

0.867 | 0.318 | 0.223 | |||

| Experimental arm | 25.81 (2.32) |

24.39 (1.84) |

24.12 (1.34) |

< 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |||

| Waist Circumference | |||||||||

| Control arm |

90.25 (6.9) |

90.25 (5.9) |

90.00 (6.0) |

1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | |||

| Experimental arm | 88.75 (8) |

85.50 (7.5) |

84.25 (7.4) |

< 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |||

| Systolic Blood Pressure | |||||||||

| Control arm |

142.00 (14) |

138.00 (8) |

137.00 (20) |

1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | |||

| Experimental arm | 140.00 (16) |

134.00 (15) |

131.00 (20) |

< 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.002 | |||

| Diastolic Blood Pressure | |||||||||

| Control arm |

87.00 (14) |

87.00 (7) |

86.00 (8) |

1.000 | 1.000 | 0.794 | |||

| Experimental arm | 86.00 (9) |

85.00 (8) |

83.00 (6) |

< 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |||

The first health outcome has 4 components: 1) body mass index behaviors, 2) waist circumference, 3) systolic blood pressure, and 4) diastolic blood pressure.

Multiple pairwise comparisons were performed between each measurement point using the Bonferroni test. In the experimental arm, significant differences in body mass index, waist circumference, systolic blood pressure, and diastolic blood pressure level related to obesity were observed between the pre-test (baseline) (Median = 25.81, IQR = 2.32), (Median = 88.75, IQR = 8), (Median = 140.00, IQR = 16), (Median = 86.00, IQR = 9) and post-test at 12 weeks (program ended) (Median = 24.39, IQR = 1.84), (Median = 85.50, IQR = 7.5), (Median = 134.00, IQR = 15), (Median = 85.00, IQR = 8) respectively, between the pre-test and the post-test at 16 weeks (follow-up) (Median = 24.12, IQR = 1.34), (Median = 84.25, IQR = 7.4), (Median = 131.00, IQR = 20), (Median = 83.00, IQR = 6) respectively, and between the post-tests at 12 and 16 weeks. In contrast, the control arm showed no significant differences in body mass index, waist circumference, systolic blood pressure, and diastolic blood pressure level between any of the measurement points: pre-test (Median = 25.37, IQR = 2.91), (Median = 90.25, IQR = 6.9), (Median = 142.00, IQR = 14), (Median = 87.00, IQR = 14), post-test at 12 weeks (Median = 25.31, IQR = 3.23), (Median = 90.25, IQR = 5.9), (Median = 138.00, IQR = 8), (Median = 87.00, IQR = 7), and post-test at 16 weeks (Median = 25.10, IQR = 3.19), (Median = 90.00, IQR = 6), (Median = 137.00, IQR = 20), (Median = 86.00, IQR = 8) respectively, as shown in Table 2.

Subsequently, total health literacy scores at each measurement point were compared between the control and experimental arms using the Mann–Whitney U test. The results showed no significant difference between the two groups at the pre-test (baseline) (p = 0.250). However, significant differences were found at the post-test conducted at 12 weeks (program completion) (p < 0.001) and at 16 weeks (follow-up) (p < 0.001), with higher scores observed in the experimental arm, as shown in Table 3.

Subsequently, total health behaviors scores at each measurement point were compared between the control and experimental arm using the Mann–Whitney U test. The results showed no significant difference between the two groups at the pre-test (baseline) (p = 0.611). However, significant differences were found at the post-test conducted at 12 weeks (program completion) (p < 0.001) and at 16 weeks (follow-up) (p < 0.001), with higher scores observed in the experimental arm, as shown in Table 3.

Furthermore, body mass index, waist circumference, systolic blood pressure, and diastolic blood pressure level at each measurement point were compared between the control and experimental arms using the Mann–Whitney U test. The results showed no significant difference between the two groups at the pre-test (baseline) (p = 0.180), (p = 0.681), (p = 0.941), and (p = 0.880), respectively. However, significant differences were found at the post-test conducted at 12 weeks (program completion) (p = 0.003), (p = 0.002), (p = 0.002), and (p = 0.002), respectively. At 16 weeks (follow-up) (p = < 0.001), (p = < 0.001), (p = < 0.001), and (p = < 0.001), respectively, with higher scores observed in the experimental arm, as shown in Table 3.

| Comparison Median |

Control Arm (n = 68) |

Experimental Arm (n = 68) |

p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | ||||

| Total Health Literacy | |||||

| Pre-test | 102.5 (24) | 98.00 (12) | 0.250 | ||

| Post-test at 12 weeks | 103.50 (27) | 125.50 (20) | <0.001 | ||

| Post-test at 16 weeks | 103.50 (23) | 133.00 (10) | < 0.001 | ||

| Total Health Behaviors | |||||

| Pre-test | 51.00 (7) | 52.00 (7) | 0.611 | ||

| Post-test at 12 weeks | 51.00 (6) | 65.00 (8) | <0.001 | ||

| Post-test at 16 weeks | 50.00 (4) | 65.00 (3) | <0.001 | ||

| Body Mass Index | |||||

| Pre-test | 25.37 (2.91) | 25.81 (2.32) | 0.180 | ||

| Post-test at 12 weeks | 25.31 (3.23) | 24.39 (1.84) | 0.003 | ||

| Post-test at 16 weeks | 25.10 (3.19) | 24.12 (1.34) | < 0.001 | ||

| Waist Circumference | |||||

| Pre-test | 90.25 (6.9) | 88.75 (8) | 0.681 | ||

| Post-test at 12 weeks | 90.25 (5.9) | 85.50 (7.5) | 0.002 | ||

| Post-test at 16 weeks | 90.00 (6.0) | 84.25 (7.4) | < 0.001 | ||

| Systolic Blood Pressure | |||||

| Pre-test | 142.00 (14) | 140.00 (16) | 0.941 | ||

| Post-test at 12 weeks | 138.00 (8) | 134.00 (15) | 0.002 | ||

| Post-test at 16 weeks | 137.00 (20) | 131.00 (20) | < 0.001 | ||

| Diastolic Blood Pressure | |||||

| Pre-test | 87.00 (14) | 86.00 (9) | 0.880 | ||

| Post-test at 12 weeks | 87.00 (7) | 85.00 (8) | 0.002 | ||

| Post-test at 16 weeks | 86.00 (8) | 83.00 (6) | < 0.001 | ||

3.3. Comparisons of the Second Health Outcomes between the Control and the Experimental Arms at Each Point of Measurement

The second health outcome has 5 components: 1) total cholesterol, 2) LDL-cholesterol, 3) HDL-cholesterol, 4) triglyceride, and 5) fasting plasma glucose.

The scores of total cholesterol, LDL-cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol, triglycerides, and fasting plasma glucose levels at each point of measurement between the control and experimental arms were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test. The results showed no significant difference in total cholesterol, LDL- cholesterol, HDL- cholesterol, triglyceride and fasting plasma glucose levels between the experimental and control arms at pre-test (baseline) (p = 0.939), (p = 0.836), (p = 0.904), (p = 0.649), (p = 0.915) respectively. However, the scores were significantly different between the experimental and control arms at the post-test at 16 weeks (follow-up) (p < 0.001), (p < 0.001), (p = 0.004), (p = 0.047), and (p < 0.001), respectively.

When comparing total cholesterol, LDL-cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol, triglyceride and fasting plasma glucose level within the same groups before and after the experiment using Wilcoxon signed rank test, the findings showed no significant difference in the control arm between pre-test (baseline) and post-test at 16 weeks (follow-up) (p = 0.117), (p = 0.667), (p = 0.611), (p = 0.184), (p = 0.378) respectively. However, in the experimental arm, the scores were significantly different between pre-test (baseline) and post-test at 16 weeks (follow-up) (p = < 0.001), (p = < 0.001), (p = < 0.001), (p = < 0.001), (p = < 0.001) respectively as shown in Table 4.

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. Effect of the Program on Health Literacy About Obesity

The findings indicated that after participating in the program, the health literacy regarding overweight and obesity among participants in the experimental arm who were pre-aging and overweight or obese was significantly higher than before the intervention and higher than in the control arm. This finding supported the research hypothesis.

| Comparison Median |

Control Arm (n = 68) |

Experimental Arm (n = 68) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | ||

| Total Cholesterol | |||

| Pre-test | 216.00 (53) | 218.00 (44) | 0.939 |

| Post-test at 16 weeks | 215.00 (52) | 197.00 (22) | <0.001 |

| p = 0.117 | p = < 0.001 | ||

| LDL- Cholesterol | |||

| Pre-test | 145.50 (46) | 147.50 (41) | 0.836 |

| Post-test at 16 weeks | 139.00 (43) | 117.50 (51) | < 0.001 |

| p = 0.667 | p = < 0.001 | ||

| HDL- Cholesterol | |||

| Pre-test | 50.50 (8) | 51.00 (11) | 0.904 |

| Post-test at 16 weeks | 48.50 (10) | 53.00 (13) | 0.004 |

| p = 0.611 | p = < 0.001 | ||

| Triglyceride | |||

| Pre-test | 128.00 (82) | 132.50 (75) | 0.649 |

| Post-test at 16 weeks | 129.00 (85) | 117.50 (50) | 0.047 |

| p = 0.184 | p = < 0.001 | ||

| Fasting Plasma Glucose | |||

| Pre-test | 96.50 (26) | 96.00 (28) | 0.915 |

| Post-test at 16 weeks | 97.00 (27) | 91.00 (11) | 0.001 |

| p = 0.378 | p = < 0.001 |

The participants in the experimental arm were given a learning experience designed to enhance each individual’s ability to search for and comprehend health information, engage in interaction and inquiry, make informed decisions to change certain behaviors, and manage their own health. This program also aimed to empower participants to share their knowledge with others. According to the Department of Health's concept, a health-literate person comprises six key components: 1) access; 2) understanding; 3) interaction, questioning, and exchange; 4) decision-making; 5) behavior change; and 6) communication skills [9]. Moreover, this program had designed relevant materials to support its activities. These included PowerPoint slides, novel instruments for fostering nutrition education, as well as yearly calendars, worksheets, documents on color-coded dietary recommendations, stretching and breathing exercises to relieve stress, and, most importantly, knowledge exchange with health role models. Contact measures were also employed, such as letters and phone calls. Furthermore, the World Health Organization has emphasized the importance of health literacy and encouraged its member states to mobilize efforts to strengthen the health literacy of their populations [7].

Moreover, during this period of unprecedented sociocultural change and vast information availability, a framework for the effective use of health information must be established. Therefore, it was considered essential that health literacy receive the requisite attention [15]. The average health literacy score among Thai respondents was 88.72 out of a maximum of 136, accounting for 65% of the total possible score. On the other hand, more than 19% of the Thai population was reported to have insufficient health literacy [16].

The present study revealed that the implementation of a health literacy promotion program targeting health behaviors and outcomes among pre-elderly individuals who were overweight or obese, in the form of a health literate bulletin, demonstrated the highest potential for mastery. This discovery was in line with other health literacy improvement techniques in which health team members also participated, contributing to significant improvements in the targeted outcomes and overall health literacy levels [17]. Furthermore, previous studies have reported similar trends. For example, among participants who identified as Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islanders in the United States, the use of the Newest Vital Sign (NVS) health literacy tool revealed that 45.3% achieved high scores. Low NVS scores were more prevalent among individuals with higher BMI and increasing age [13]. A systematic review further confirmed that in 17 out of 22 studies, subjects with low health literacy were significantly associated with being overweight, obese, or having a high BMI [10]. Furthermore, research conducted in Taipei demonstrated that among individuals undergoing health check-ups, higher BMIs are associated with lower health literacy [11]. In addition, a study from Albania also found a strong positive association between BMI and health literacy: the odds of being overweight/obesity were twice as high among individuals with insufficient health literacy compared to participants with very good health literacy [18].

After receiving the health literacy enhancement program targeting health behaviors and health outcomes in pre-elderly individuals who were overweight and obese, the health literacy scores regarding overweight and obesity of the participants in the experimental arm were better than those of the control arm. This finding aligned with a health literacy and behavior improvement program implemented among working-age individuals living in rural areas of northeastern Thailand. The program resulted in a significantly higher average health literacy score compared to their baseline scores and those of the control arms [19]. Similarly, this outcome aligns with another health literacy promotion strategy, which involved a tuberculosis case study as its target. Patients with dyslipidemia attending the outpatient department of a hospital in eastern Thailand participated in this study. The experimental arm achieved significantly higher average health literacy scores compared to both their pre-intervention scores and those of the control arm post-intervention [20].

However, these findings contrast with an earlier investigation on Black women residing in the United States, who had a body mass index ranging between 25 kg/m2 and 34.9 kg/m2. The patients enrolled in the Shape Program Intervention attended the 18-month evaluation visit and completed health literacy assessments; the Newest Vital Sign (NVS) was assessed orally. It was observed from the investigation that in the event of low health literacy, the prevention of substantial weight gain was still successfully achieved [21]. Another study, titled *Effect of a community-based participatory health literacy program on health behaviors and health empowerment among community-dwelling older adults: A quasi-experimental in nature*, indicated that the health literacy intervention had no significant long-term effects on health behaviors. The literature review suggested that most interventions of this sort may be effective in producing short-term behavioral changes in participants; however, maintaining those changes over time remains a challenge [14]. Certainly, health literacy is crucial in managing chronic diseases. To cope with chronic or long-term conditions on a daily basis, people must be able to analyze and evaluate health information in the form of complex treatment schemes, adjust their lifestyles, and make informed decisions when seeking healthcare [22].

4.2. Effect of the Program on Health Behaviors about Obesity

The findings showed that after receiving the program, the health behaviors about overweight and obesity among pre-aging individuals with overweight and obesity were higher than before receiving the program and higher than in the control arm. This finding supported the research hypothesis.

The participants were the pre-aging individuals aged 45–59 years, a group experiencing physiological changes due to declining hormone levels and physical deterioration. Consequently, their health problems differ from those of other groups. For example, pre-aging women have hyperlipidemia, urinary incontinence, and irritation [5]. Therefore, preparation for pre-aging is important, and all people must be aware of and adapt to it [23]. By considering obesity, defined as the excessive accumulation of body fat that adversely affects health, obesity results from an energy imbalance that leads to excessive fat accumulation [24].

This scientific research discovered that participants in the experimental arm received instruction in health-related behaviors, including actions to take or avoid in order to influence their health. The health practices were the observable ones, and the unobservable ones involve measurable changes, encompassing the four dimensions of health: physical, mental, emotional, and social health behaviors, which are interconnected in a balanced manner. Failure to adhere to healthcare practices, such as selection of good food, regular exercise, and mood management, has been identified as a significant contributor to obesity or overweight [25]. In addition, the successful outcome of weight loss and waist circumference reduction was attributed to three key factors: dietary changes, exercise, and emotional and psychological control [26].

This research study demonstrated that participants in the experimental arm, who had followed the health literacy program focused on improving health behaviors and outcomes among pre-aging individuals with overweight and obesity, could, for the first time, experience an improvement in their health behavior scores related to overweight and obesity. A survey conducted in Bangladesh, involving a large number of household heads living in selected suburban areas (with an average age of 51 years), provided evidence that a higher magnitude of health literacy could indeed lead to a decrease in overweight and obesity. Health literacy indicators such as information sharing and health behaviors were found to influence BMI [27].

Furthermore, this study also found that after receiving the health literacy program, participants in the experimental arm showed improved health behavior scores related to overweight and obesity were better than those in the control arm. This result was consistent with previous health promotion programs, in which the average health behavior scores of the experimental arm, after 4, 8, and 12 weeks, were significantly higher than those of the control arm [28]. Additionally, a study among overweight employees in the workplace found that the mean scores for eating behaviors and physical activity behaviors in the experimental arm were also significantly higher than those of the control arm [29].

4.3. Effect of the Program on Health Outcomes

The findings showed that after receiving the program, the health outcomes among pre-aging individuals with overweight and obesity were better than before receiving the program and better than the control arm. This finding supported the research hypothesis.

Obesity is related to several adverse outcomes, including physical pain, discomfort, and reduced quality of life, as well as psychological conditions, including body image dissatisfaction, low self-esteem, elevated stress levels, and depressive symptoms [2]. Additionally, obesity dramatically increases the risk of developing cardiovascular and vascular diseases, hypertension, insulin resistance that may lead to type 2 diabetes, and dyslipidemia characterized by elevated triglycerides and Low-Density Lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol levels along with decreased High-Density Lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol levels [30]. The health outcomes indicators assessed in this study included the following: 1) body mass index, 2) waist circumference, 3) systolic blood pressure, 4) diastolic blood pressure, 5) total cholesterol, 6) LDL-cholesterol, 7) HDL-cholesterol, 8) triglyceride, and 9) fasting plasma glucose.

This study revealed that, following participation in the health literacy enhancement program, participants in the intervention group demonstrated improvements in health behaviors and outcomes compared to their baseline levels, exceeding those observed in the control arm. This is consistent with a study involving hotel staff with high blood lipids, which showed a significant decrease in cholesterol levels after participating in the course [31]. A survey conducted among obese adults in the United States demonstrated reductions in BMI, fasting plasma glucose, and the triglyceride/HDL cholesterol ratio [32]. Moreover, a study of individuals at risk of chronic diseases found that active participation in the program resulted in significant decreases in body weight, waist circumference, and blood lipid levels [33]. Another study among medical school faculty members showed that BMI, waist circumference, blood glucose levels, triglyceride levels, total cholesterol, and LDL-cholesterol levels decreased, while HDL-cholesterol levels increased [34]. Individuals should set health goals for themselves to avoid overweight and obesity, which cause most of the chronic diseases. People should reflect on the underlying causes of their overweight and obesity in order to identify suitable strategies for change and develop a personalized plan to prevent this condition in an approach that fits their lifestyle [35].

4.4. The Implications of the Findings

- These findings were the evidence supporting the health literacy concepts as the guidelines for developing the health-promoting program for the pre-aging group with overweight and obesity.

- The health literacy development program for the health behaviors and results of the pre-aging group with overweight and obesity could be used by nurses and public health officers in everyday care or integrated with local health programs in order to plan activities for the pre-aging group with overweight and obesity.

- To use this program, the target group not only joins the activities of the program created by the researcher, but the group can also mutually learn from the health role models.

- The policy makers could apply the findings to developing the health literacy and planning the health promotion activities for the pre-aging group with overweight and obesity. Contents or concepts could also be included in the anti-NCDs program for Thai people that might be created in the future.

4.5. Limitations

- The budget limitation included the body component analysis tools not being used for analyzing the body fat percentage.

- The difficulties in conducting the activities of the program might be a burden on the researcher/officer. The number of research assistants should be increased.

- The variable relationship limitations were the knowledge about overweight and obesity, as well as the health behaviors associated with overweight and obesity.

4.6. Recommendations for Further Research

- Further research studies should develop and examine the effectiveness of the health literacy promotion programs on health behaviors and health outcomes among pre-aging groups with overweight and obesity in different settings that including urban and rural communities.

- Further research studies should use Participatory Action Research (PAR) and Research and Development (R&D) to develop the health literacy promotion programs on health behaviors and health outcomes among pre-aging individuals with overweight and obesity, as well as modern applications such as TikTok, in order to shorten the programs’ periods.

- The pre-aging group with overweight and obesity should be followed up for at least six months.

CONCLUSIONS

- After taking the health literacy development program for the health behaviors and the health outcomes of the pre-aging group individuals with overweight and obesity, the health literacy score for the overweight and the obese as well as the behavior scores for the overweight and the obesity of the experimental arm was higher than that before taking the program, the health outcomes of the experimental arm were better than that before taking the program.

- After taking the health literacy development program for the health behaviors and the health outcomes of the pre-aging group with overweight and obesity, the health literacy scores and the health behaviors scores about the overweight and the obesity of the experimental arm were higher than that of the controlled arm, the health outcomes of the experimental arm were better than that of the controlled arm.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: J.W.: Study conception and design; E.C.: Conceptualization; P.S.: Data collection; P.O.: Data analysis and interpretation; All of the authors have reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| BMI | = Body Mass Index |

| LDL-cholesterol | = Low-Density Lipoprotein cholesterol |

| HDL-cholesterol | = High-Density Lipoprotein cholesterol |

| WHO | = World Health Organization |

| DALYs | = Disability Adjusted Life Years |

| IOC | = Item-Objective Congruence |

| SPSS | = Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

| NVS | = Newest Vital Sign |

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

The study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Ethical Review Board of the Faculty of Public Health, Chiang Mai University,Thailand (Approval No. ET046/2566). This study was not registered in a public clinical trial registry prior to participant enrollment due to the institutional requirement at the time not mandating trial registration for academic RCTs without external funding.

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or research committee and with the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki, as revised in 2013.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Informed consent was waived for this retrospective study, as the exclusive use of de-identified patient data posed no potential harm or impact on patient care.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIAL

The data supporting the findings of the article are available from the corresponding author [J.W] upon reasonable request and will be considered on a case-by-case basis as appropriate.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank the participants among Pre-aging Individuals with Overweight and Obesity who participated in this study. Additionally, the authors gratefully acknowledge the Faculty of Public Health, Chiang Mai University, which played a vital role in supporting the successful completion of this research.