All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Village Health Workers’ Roles in Primary Health Care in Beitbridge District, Zimbabwe: A Quantitative Exploration of the Challenges and Strategies for Improvement

Abstract

Introduction

Village health workers play a crucial role in primary healthcare. Numerous challenges impact their effectiveness and efficiency in service delivery. The study aimed to determine the extent of the Village Health Workers’ roles, challenges, and strategies to improve service delivery in the Beitbridge district, Zimbabwe.

Methods

A cross-sectional survey was conducted to collect data from 129 rural and urban Village Health Workers on their socio-demographic characteristics, the extent of their roles, challenges, and strategies for improving service delivery. Descriptive and inferential statistics were used to analyse data.

Results

The weighted average for the roles was 3.32; health education was the most frequently conducted activity, with a mean rank of 4.03. Other activities carried out were patient referrals, disease surveillance, and child growth monitoring, with mean ranks of 3.98, 3.57, and 3.50, respectively. With a weighted mean of 3.67 on the challenges, Village Health Workers often receive inadequate allowances and medical equipment (mean scores of 4.29 and 421, respectively). They frequently cannot access remote areas and have limited knowledge on managing some common ailments (mean scores of 3.88 and 3.71, respectively). No significant differences were found in the challenges faced by urban and rural Village Health Workers (p-values > 0.05). However, the latter frequently encountered difficulties accessing remote areas (U = 154.5; p-value = 0.000*). Mobile health technology, integration into the healthcare system, and adequate resource provision (ranked 4.51, 4.45, and 4.31; weighted mean 4.27) were suggested for improving service delivery.

Discussion

Quantitative contextual insights on Village Health Workers’ roles and challenges are used to inform local policy programming.

Conclusion

The extent of Village Health Workers' roles, challenges, and strategies for improving service delivery was provided. This could provide valuable insights for policymakers, program managers, and stakeholders seeking to improve service delivery.

1. INTRODUCTION

As the Alma-Ata Declaration advocates, primary health care (PHC) is vital to achieving universal health coverage (UHC) [1]. However, inadequate resourcing and equipping of health systems, coupled with endemic shortages of healthcare workers, hamper essential healthcare services. African and Asian countries reportedly have a healthcare worker shortfall of over 4 million [2].

Countries were recommended to tap into the potential of Community Health Workers (CHWs) to bridge gaps in healthcare [3]. CHWs are lay healthcare workers selected by their local communities and receive standardised training outside the conventional medical curriculum, which helps them deliver HC services [4]. In Zimbabwe, CHWs are known as Village Health Workers (VHWs) and assist in providing PHC services in their local communities, including health promotion and education, diagnostic and treatment of minor health ailments, community-based disease surveillance, maternal and child health, and referral of complicated conditions to health facilities [5].

Globally, CHWs help foster collective, community-driven, collaborative approaches and promote local accountability [6]. Their role continues to evolve across different health systems, with tasks shifting and now dominating to include curative care and case management with professional nurses [7]. In high-income countries, their role has changed towards managing non-communicable diseases such as hypertension and diabetes [8]. However, in low-income countries, these are used to control infectious diseases. On the other hand, the double disease burden has compelled emerging economies such as Bangladesh, Brazil, Iran, Rwanda, and South Africa to have CHWs address both communicable and non-communicable diseases, after achieving satisfactory outcomes in maternal and child health and controlling TB and malaria [4, 6].

Community health workers in some African countries continue to face challenges in service delivery [7]. An unsustainable workload has contributed to CHWs' burnout [9]. A study in Tanzania revealed that one village had 289 households, which were covered by one CHW who was not even provided with a means of transportation. In some settings, CHWs are not paid any salaries/allowances, and subsidise community health activities with out-of-pocket funding [10]. In Malawi, poor quality of service delivery by CHWs has been reported as a result of inadequate training opportunities, while in Nigeria, they have been affected by a lack of equipment, which hinders the translation of theory to practice [11].

Globally, some innovative programs were applied to enhance community health programs. These include community engagement, fostering partnerships with local communities, and technology integration [12]. Based on continuous feedback mechanisms and evaluation, such programs should be designed to adapt to the ever-changing community health needs [12]. Such models were found to be successful in countries like Bangladesh, Brazil, Cuba, and Rwanda [13]. They had sustainability mechanisms for scaling up to the broader population through ongoing funding, community support, and policy integration, leveraging technology for real-time data transmission, telemedicine, and remote consultations [14]

The poor performance of the Zimbabwean economy has pushed many nurses and doctors to migrate to developed countries, notably the United Kingdom and Australia [15]. In 2015, the country had eight healthcare workers per 10,000 people, falling short of the World Health Organisation (WHO) standard of 23 per 10,000 [5, 16]. The shortage of health service providers, particularly nurses, has compelled the Zimbabwean health system to rely on VHWs to complement the existing staff in delivering Primary Health Care (PHC) services.

In the early 1980s, Zimbabwe sought to provide PHC services equitably among the populace as part of its egalitarian reforms. It trained many VHWs to deliver community health services with varying degrees of effectiveness [17]. The economic recession of the early 2000s has contributed to poor health outcomes, with the Infant Mortality Rate increasing from 53 to 56 per 1,000 live births between 1992 and 2016 [18]. The maternal mortality rate remains high at 443 per 100,000, exceeding the expected Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) target of 70 per 100,000 [19]. Beitbridge district, by its geographic location as the busiest inland port city and being along the transport corridor in the SADC region, has three-quarters of the Matabeleland South Province’s 21% HIV/ AIDS prevalence, which is co-morbid with TB [20-22]. To revitalise the VHW Program, the VHW Strengthening Plan of 2017 was developed but never operationalised due to role ambiguity, service duplication, and limited coordination [16]. This study seeks to quantitatively explore the VHWs' roles and challenges, and strategies that could be implemented to improve primary healthcare service delivery [16].

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Study Design

An exploratory sequential mixed-methods design, consisting of two stages, was employed. The first stage involved a qualitative study that explored the roles, challenges, and strategies for improving the effectiveness and efficiency of VHWs in service delivery within the Beitbridge district, Zimbabwe [47]. The second stage, reported here, involved a cross-sectional survey of 134 VHWs using a questionnaire, which was used to validate and generalise the findings from the qualitative first stage mentioned above. This study design is generally quick and easy to conduct, and there was no risk of loss to follow-up for the VHW participants since the questionnaire was only administered once [23].

2.2. Study Setting

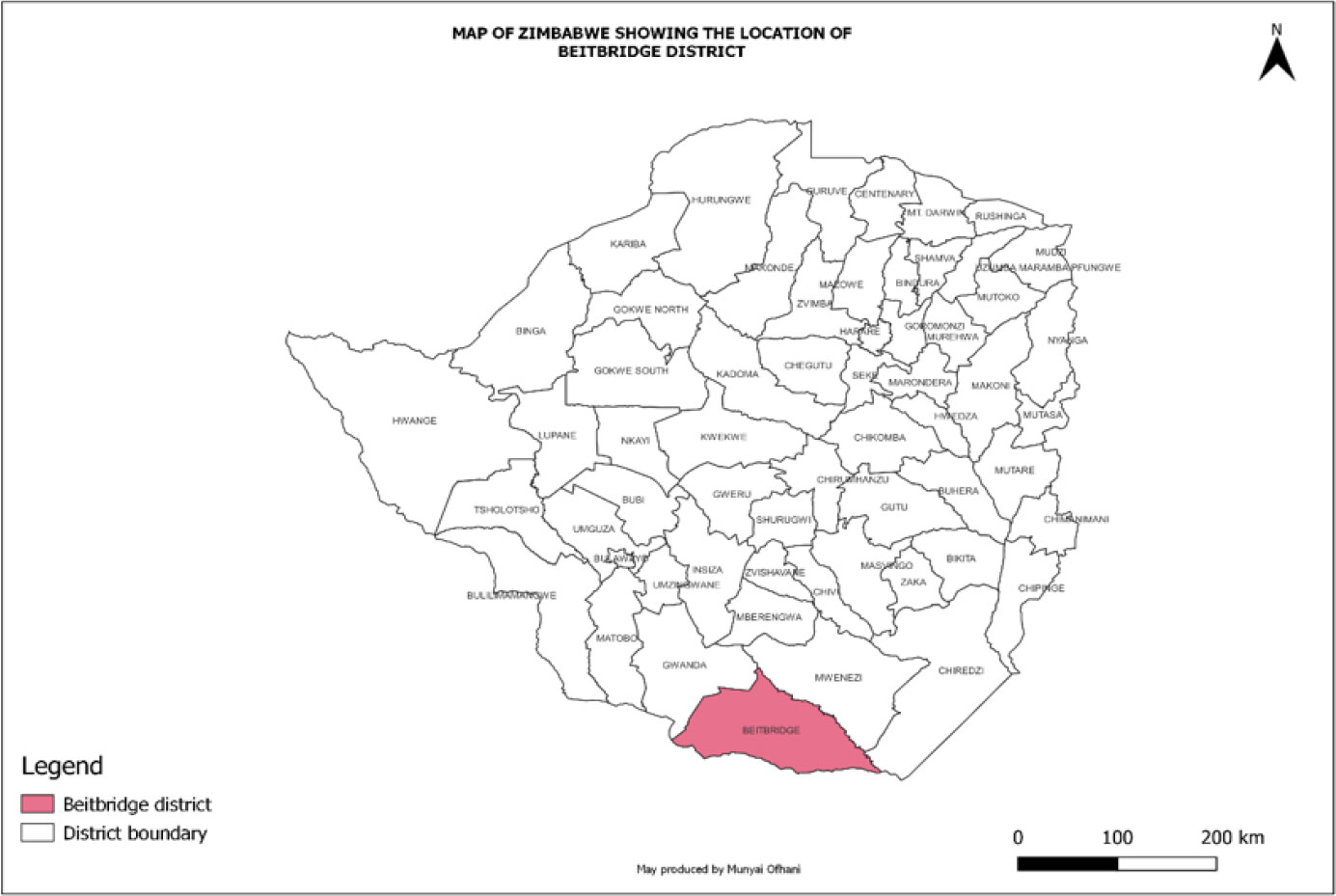

The study was conducted in Zimbabwe's Beitbridge, Matabeleland South province (Fig. 1). There are 15 Wards and 18 health centres in the rural area. The urban area has 6 Wards, one clinic, and a referral hospital [16]. According to the 2022 population census, the district had 152,574 inhabitants, of whom 94,000 resided in rural areas and 58,574 in urban areas [16]. The local languages spoken are Tshivenda, IsiNdebele, ChiShona, and Sesotho. The demographic age structure is bottom-heavy, with nearly 70% being 35 years and below [16], potentially presenting a high demand for PHC services. The study area was purposively selected, as there is a heavy reliance on VHWs to deliver essential healthcare services to the relatively young population, who are in dire need of maternal and reproductive health services, and have a high burden of infectious diseases [16].

The location of the Beitbridge district in Zimbabwe.

2.3. Study Population and Sampling

The target population was 286 VHWs in the Beitbridge district. A sample size of 134 (representing 46.9% of the target population of 286) was calculated using the EPI INFO (Version 7) software based on a 95% Confidence Interval, 80% Statistical Power, a 5% Margin of Error, a Design Effect of 1, and an Expected Frequency of 50%. This calculation increased the likelihood of detecting statistically significant effects in the sample [24]. A systematic review by White involving 1750 articles published in Scopus-indexed journals found that, while the size of the target population can constrain the sample size, a minimum sample size of 100 is adequate for statistical inference from that population. The same review found that 89% of the articles met the threshold [25]. All the VHWs in Beitbridge district who were listed in the health facility registers and had worked for at least 6 months in the same facility before data collection were eligible for selection to participate in the study. Systematic random sampling was preferred for selecting study respondents due to its suitability for highly dispersed populations and its ability to provide a generally accurate representation of the target population [26]. The sampling interval of 2.13 (i.e., rounded down to 2.0) was obtained by dividing the target population of 286 by the sample size of 134. The VHW register provided the sampling frame, and the first person on it was selected as the first respondent. Subsequently, sampling followed a pre-determined sample interval to select other respondents. The influence of specific confounders was controlled by restricting the study to VHWs only, rather than including other healthcare workers in the same survey, thereby minimising variability. Another control measure was random sampling, which assumed that random distribution effects across urban and rural groups [27, 28].

2.4. Data Collection

Data were collected using a structured questionnaire by two social science graduates after obtaining prior written informed consent from the participants. The instrument was pilot-tested on 13 VHWs from non-participating rural health centres with the questions adjusted until good internal consistency and reliability were achieved (Cronbach Alpha [α] = 0.82), having been measured by correlating the scores through a test-retest data collection and analysis process on the same respondents [29]. The questionnaire consisted of questions on the VHWs’ socio-demographic characteristics, a 5-point ordinal ranking scale for the frequency of occurrence of roles, challenges faced, and their perception of suggested strategies to improve effectiveness and efficiency in service delivery, from which the participants were to choose. The Likert scale for the role and challenges ranged from “Rarely”, “Occasionally”, “Frequently”, “Often”, and “Always”, while that for the strategy was “Not Important”, “Low”, “Medium”, “High”, and “Very High”. The average time taken to administer the questionnaire was 22 minutes. The study respondents were recruited from July 13, 2024, to August 29, 2024.

The study was conducted following the principles of the Helsinki Declaration on human subjects, as the protocol was approved by the University of Venda Research Ethics Committee and the Medical Research Council of Zimbabwe. All the study participants provided written informed consent. During the informed consent process, participants received a thorough verbal explanation of the research aims and what it entails, along with an opportunity to ask questions and seek clarification before the questionnaire was administered. We also documented the informed consent process and participants' understanding. We ensured comprehension of informed consent by assessing participants' knowledge through discussions and encouraged feedback to identify areas of confusion. Finally, we sought re-consent if changes could occur during data collection. Participants' rights were respected through autonomy and decision-making capacity, and confidentiality was ensured throughout the research.

2.5. Data Analysis

The data collected was captured and analysed using the IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) Version 24, with the assistance of a statistician. Socio-demographic characteristics such as sex, age group, level of education, distance from the VHWs’ residence to their local clinics, the distance to the furthest homesteads to be visited, and the number of households visited were presented in tables as frequency counts and percentages. Central tendency and dispersion measures, such as medians, interquartile range, and box-and-whisker plots, were used to compare the households visited in one month for both urban and rural VHWs. These measures provide a complete and nuanced understanding of the data sets for the two groups, helping to identify outliers and assess variability [30]. A non-parametric median test was applied to compare the households that the two independent groups visited. The VHWs’ perceptions of the extent of specific roles, challenges faced, and suggested strategies were compared using their ranked means against their weighted averages. A Mann-Whitney U test (Wilcoxon Rank Sum Test) was used to compare the medians of the challenges faced by urban and rural VHWs at the 95% confidence level. This test was preferred under the assumptions that the two groups were not normally distributed, that they came from the same population, and that the variables being compared were continuous and ranked [31].

3. RESULTS

3.1. Socio-demographic Characteristics (n=20 urban and 109 rural)

There were 129 (96.3%) out of the 134 expected VHW respondents, of which 84.5% were from rural Beitbridge. Females comprised the overwhelming majority of the respondents, with over 90%. The urban respondents were relatively young; the modal age group was 40-44 (40%). In contrast, the rural counterparts were generally older and had an almost bimodal age distribution, with the 45- to 49-year-old (33.0%) and over 50-year-old (33.9%) age groups being the most predominant. Nearly 70% of the respondents had secondary education, with only one person (from the rural areas) having no formal education. Most of the urban respondents stay within a 2 km radius of the places they serve. On the other hand, 50% of the rural VHW respondents cover a radius of at least 5 km and travel approximately the same distance to their nearest health facilities (Table 1).

3.2. The Extent Of Roles Played by VHWs

Table 2 shows that the weighted mean for the ranked roles of VHWs was 3.32, obtained by dividing the sum of the mean values across all roles by 7. This value was used as a benchmark to determine how the VHW practices each role, with values below the weighted mean interpreted as indicating a low extent, and vice versa for values above the mean, which is 3.32. Most respondents conduct health education more often than any other activity (mean rank: 4.03, weighted mean: 3.32). Village Health Workers also reportedly conduct disease surveillance and monitor child growth. They refer patients to health facilities when they cannot manage specific ailments (mean ranks 3.57, 3.50, and 3.50, respectively, against the weighted mean of 3.32). On the other hand, only a handful of respondents have also shown that they occasionally diagnose and treat minor ailments and offer family planning and immunisation services (mean ranks: 3.16, 2.72, and 2.3, respectively, against the weighted mean of 3.32).

In this study, a decision was made based on the respondents’ mean rank for each role compared to the weighted average value of 3.323, calculated by summing the mean values of the items and dividing by the total number of items.

3.3. Households Visited in a Month

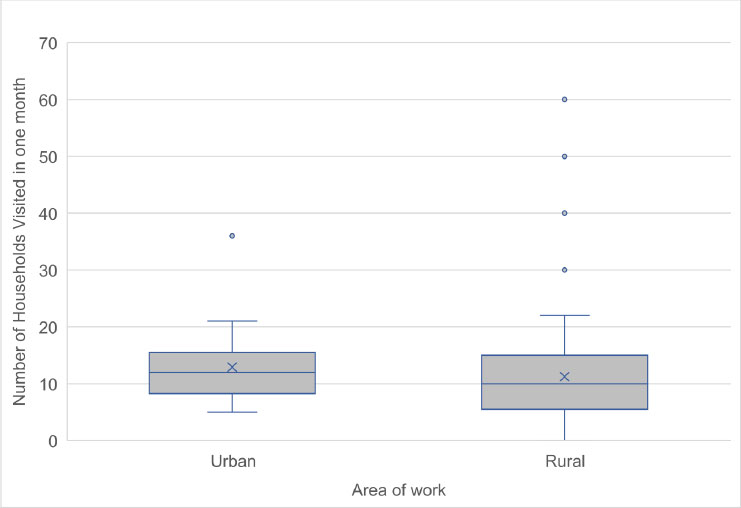

The median number of households visited per month in urban areas was 12 (interquartile range [IQR]: 5-21) and in rural areas, 10 (IQR: 0-22) (Fig. 2).

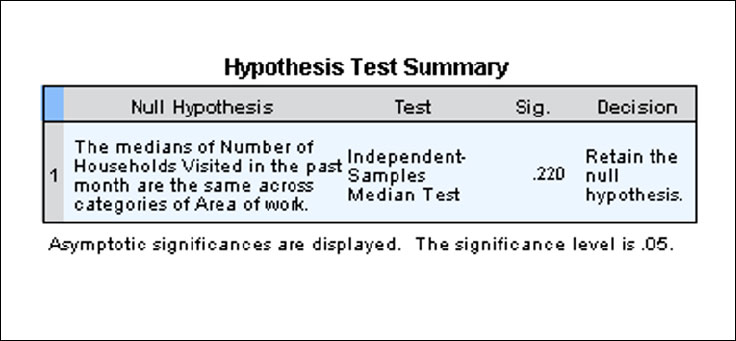

A nonparametric median test was conducted at the 95% confidence level to compare the median number of households visited by VHWs in urban and rural areas over one month. A p-value of 0.220 was obtained, indicating no significant difference (Fig. 3)

Table 1.

|

Urban n (%) |

Rural n (%) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 0 (0) | 6 (5.5) |

| Female | 20 (100) | 103 (94.5) | |

| Age in years | 25-29 | 1 (5.0) | 0 (0) |

| 30-34 | 0(0) | 0(0) | |

| 35-39 | 3 (15.0) | 11 (10.1) | |

| 40-44 | 8(40.0) | 25(22.9) | |

| 45-49 | 7(35.0) | 36 (33.0) | |

| 50+ | 1(5.0) | 37 (33.9) | |

| Level of education | None | 0 | 1(0.9) |

| Primary | 1(5.0) | 39 (35.8) | |

| Secondary | 19 (95.0) | 69 (63.3) | |

| Tertiary | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Duration of staying in the area of work | Less than 1 year | 0 (0.0) | 0(0.0) |

| 1 to 2 years | 1 (5.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| 2 to 3 years | 2(10.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| 3 to 4 years | 3(15.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Over 4 years | 12 (60.0) | 109 (100.0) | |

| Furthest homestead | Less than1 km | 0(0.0) | 1(0.9) |

| 1 to 2 km | 16(80.0) | 7(6.4) | |

| 2 to 3 km | 3(15.0) | 15(13.8) | |

| 3 to 4 km | 1(5.0) | 16(14.7) | |

| 4 to 5 km | 0(0.0) | 15(13.8) | |

| Over 5 km | 0(0.0) | 55(50.5) | |

| Distance to nearest health facility | Less than1 km | 2(10.0) | 3(2.8) |

| 1 to 2 km | 12(60.0) | 7(6.4) | |

| 2 to 3 km | 5(25.0) | 12(11.0) | |

| 3 to 4 km | 1(5.0) | 12(11.0) | |

| 4 to 5 km | 0(0.0) | 13(11.9) | |

| Over 5 km | 0(0.0) | 62(56.9) | |

| Role of VHW |

1. Rarely n (%) |

2. Occasionally n (%) |

3. Frequently n (%) | 4. Often n (%) | 5. Always n (%) | Mean Rank | Standard Deviation | Remark |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health education | 3(2.3) | 7(5.4) | 18(14.0) | 56(43.4) | 45(34.9) | 4.03 | 0.96 | High extent |

| Immunisation | 11(8.5) | 79(61.2) | 31(24.0) | 5(3.9) | 3(2.3) | 2.30 | 0.78 | Low extent |

| Family planning | 18(14.0) | 30(23.3) | 57(44.2) | 18(14.0) | 6(4.7) | 2.72 | 1.02 | Low extent |

| Diagnosing and curing minor ailments | 4(3.1) | 20(15.5) | 62(48.1) | 38(29.5) | 5(3.9) | 3.16 | 0.84 | Low extent |

| Disease surveillance | 2(1.6) | 5(3.9) | 49(38.0) | 64(49.6) | 9(7.0) | 3.57 | 0.748 | High extent |

| Child Growth Monitoring | 11(8.5) | 13(10.1) | 36(27.9) | 39(30.2) | 30(23.3) | 3.50 | 1.20 | High extent |

| Referrals | 3(2.3) | 8(6.2) | 25(19.4) | 45(34.9) | 48(37.2) | 3.98 | 1.015 | High extent |

Distribution of the measures of dispersion for urban and rural households visited by VHWs.

Median test used to compare households visited by VHWs in urban and rural Beitbridge.

3.4. The Magnitude of the Challenges Faced by VHWs in Service Delivery

Data analysis (Table 3) shows that the weighted average was 3.67 (mean values below 3.67 were considered low perception, and those above 3.67 were considered high perception). Most respondents reported a high level of concern about often facing challenges such as inadequate financial allowances and limited medical and equipment resources, which are essential to executing their roles effectively and efficiently (mean ranks: 4.29 and 4.21, respectively). Respondents also indicated that they frequently face challenges accessing remote areas and have limited knowledge and/or skills to diagnose and manage some ailments (mean ranks: 3.88 and 3.71, respectively). On the contrary, a few respondents reported occasionally encountering limited support from health facilities (mean rank: 2.28).

3.5. Comparison of the Challenges Faced by VHWs by Area of Work

The Mann-Whitney U-test was applied to the medians of the challenges faced by VHWs in urban and rural areas to determine whether there were significant differences between them. There were no significant differences by setting in the medians of the challenges (p-values > 0.05), except for rural VHWs, who reported more frequently accessing remote areas than their urban counterparts (U = 154.5; p-value = 0.000*; Pseudo R = 0.5722). Table 4 shows the test summary.

3.6. Ranking of the Proposed Strategies by VHWs

The weighted mean rank for the proposed strategies was 4.27. Mean values less than 4.27 are interpreted as a low regard, while values above 4.27 are interpreted as a high regard. Most respondents highly regarded mobile health technologies, VHW integration into the mainstream healthcare system, and timely provision of required resources (mean ranks: 4.51, 4.45, and 4.31, respectively) as strategies that could improve their effectiveness and efficiency in service delivery. Village Health Workers also advocated for improvements in transport for VHWs. A sustained community engagement program could enhance their effectiveness (mean ranks: 4.19 and 4.18, respectively) (Table 5).

| Challenge |

Rarely n (%) |

Occasionally n (%) |

Frequently n (%) | Often n (%) | Always n (%) | Mean rank | Standard Deviation | Remark |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Limited knowledge or skill | 4(3.1) | 10(7.8) | 39(30.2) | 43(33.3) | 33(25.6) | 3.71 | 1.034 | High perception |

| Limited resources | 2(1.6) | 8(6.2) | 14(10.9) | 42(3.6) | 63(48.8) | 4.21 | 0.974 | High perception |

| Accessing remote areas | 12(9.3) | 11(8.5) | 20(15.5) | 24(18.6) | 62(48.1) | 3.88 | 1.346 | High perception |

| Support from health facilities | 14(10.9) | 80(62.0) | 21(16.3) | 13(10.0) | 1(0.8) | 2.28 | 0.819 | Low perception |

| Inadequate allowances | 2(1.6) | 7(5.4) | 14(10.9) | 34(26.4) | 72(55.8) | 4.29 | 0.971 | High perception |

| Test Statisticsa | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| How often do you encounter limited knowledge or skill as a challenge? | How often do you encounter limited resources as a challenge? | How often is difficulty in accessing remote areas encountered as a challenge? | How often is limited support from healthcare facilities encountered as a challenge? | How often are inadequate allowances a | |

| Median | 4.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 2.0 | 5.0 |

| n | 129 | 129 | 129 | 129 | 129 |

| Mann-Whitney U | 1066.000 | 906.500 | 154.500 | 958.000 | 968.000 |

| Wilcoxon W | 7061.000 | 1116.500 | 364.500 | 1168.000 | 6963.000 |

| Z | -.163 | -1.297 | -6.499 | -.989 | -.884 |

| Asymp. Sig. (2-tailed) | .871 | .195 | .000 | .323 | .377 |

| R | 0.0145 | 0.1142 | 0.5722 | 0.0871 | 0.0332 |

| a. Grouping Variable: Area of Work | |||||

| Strategy suggested |

1. Not important n (%) |

2. Low Importance n (%) |

3. Medium Importance n (%) |

4. High Importance n (%) |

5. Very High Importance n (%) |

Mean Rank | Standard Deviation | Decision criteria |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Additional training | 1(0.8) | 3(2.3) | 15(11.6) | 67(51.9) | 43(33.3) | 4.15 | 0.772 | low regard |

| Adequate resources | 1(0.8) | 4(3.1) | 11(8.5) | 51(39.5) | 62(48.1) | 4.31 | 0818 | High regard |

| Improving means of transportation | 1(0.8) | 5(3.9) | 17(13.2) | 52(40.3) | 54(41.9) | 4.19 | 0.864 | low regard |

| Supportive supervision | 5(3.9) | 26(20.2) | 59(45.7) | 29(22.5) | 10(7.8) | 4.10 | 0.942 | low regard |

| Community engagement | 6(4.7) | 33(25.6) | 38(29.5) | 36(27.9) | 16(12.4) | 4.18 | 1.093 | low regard |

| Mobile technology | 1(0.8) | 3(2.3) | 12(9.3) | 26(20.2) | 87(67.4) | 4.51 | 0.678 | High regard |

| VHWs' integration into the mainstream healthcare system | 2(1.6) | 5(3.9) | 8(6.2) | 32(24.8) | 82(63.6) | 4.45 | 0.892 | High regard |

4. DISCUSSION

The study has revealed that more women are involved in community health services than their male counterparts. Perhaps this could be due to the voluntary nature of the work, as revealed by respondents in the first qualitative phase of this research, who demonstrated inadequate financial allowances [16]. Social constructs such as culture and stigma may have influenced male involvement in community health voluntary activities, as this gender is often perceived as the primary caregivers for their families; hence, they might not be willing to engage in these activities [32]. Studies in Mudzi and Mutoko Districts, Zimbabwe [5], and in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) have also revealed lower participation by women in community health activities [33]. Women seem to be generally considered better healthcare providers than men, as was revealed during the Ebola outbreaks, when Sierra Leone and Liberia enacted policies to promote more women's participation in community health services [33].

The majority of VHWs were found to have secondary education. Whilst there seems to be no policy in Zimbabwe regarding minimum formal education requirements, studies have revealed that potential VHWs are recruited on their ability to read and write [5]. Other countries like Ethiopia, India, and Pakistan require VHWs to have attained at least the 8th grade of formal education [34]. VHWS needs to be literate to cope with the ever-changing dynamics of community health services and adapt to task-shifting.

Health education seems to be the most practised role, followed by disease surveillance and child growth monitoring. Health education is central to the delivery of primary health care (PHC) by village health workers (VHWs). This is mainly carried out during household visits by urban and rural cadres to deliver health promotional messages on preventing and controlling endemic conditions, aiming to reach a target of 100 people per month [35]. This finding was consistent with a study in The Gambia. VHWs are also expected to conduct weekly visits to hold ‘health talks’ with residents on preventing and controlling endemic diarrhoea and malaria [36]. Since health education does not require many material resources, perhaps VHWs consider it the most straightforward role. Health education is the cornerstone of health service delivery as it promotes individual well-being and community and population health.

Community-based disease surveillance (CBS) is also highly practised by the VHWs. It was reported in the first stage of this sequential mixed methods research that Beitbridge was affected by a cholera outbreak in 2023 and has endemic conditions such as malaria and tuberculosis (TB). Our earlier findings from in-depth interactions with health service providers and VHWs revealed a heavy reliance on these cadres to carry out passive case finding for malaria, TB, and, more recently, COVID-19 during contact tracing. These cadres report the unusual occurrence of infirmities in their communities through ‘signals’ to the nurses in charge of their local clinics for further investigations [5]. Considering the health worker shortages in Zimbabwe and the reliance on VHWs for public health surveillance, this calls for improved capacity building of VHWs in public health surveillance. This observation was also validated by the relatively high ranking of additional training requirements as one of the strategies to improve VHW effectiveness. A scoping review of 25 low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) by Alhassan and Wills revealed the significant impact of continuous training on CBS in controlling communicable diseases, such as malaria, TB, Ebola, and COVID-19 [37].

This study revealed that VHWS occasionally diagnose and treat minor ailments and immunise against some child-killer diseases. As mentioned in the findings stage of this exploratory sequential mixed-methods research, VHWs face challenges such as a lack of timely replenishment of medical and equipment supplies. These findings can substantiate earlier findings from the qualitative component of this research, which showed that VHWs often had depleted therapeutic stocks in their medical kits. Gore et al. [5] reported that VHWs in Zimbabwe faced challenges due to the inconsistent supply of medicines like paracetamol, coartem, and malaria rapid diagnostic test (RDT) kits.

The inadequacy of resources has been cited as a challenge faced by VHWs, which could hinder their effectiveness and efficiency in service delivery. This validated our prior findings, which mentioned that two or three VHWs staying in different villages share specific basic equipment, such as baby weighing scales and mid-upper-arm circumference (MUAC) measuring tapes used in child growth monitoring. The proportion of the health service delivery against the national fiscus budget in Zimbabwe has always been less than 10%, making overall health financing a challenge [4], and this falls short of the Abuja Declaration of 2001, which had set a minimum of 15% of the total national budget for the improvement of the health delivery system [38]. Most Southern African Development Community (SADC) countries serving South Africa have struggled to meet this target, mainly relying on external donor funding [39]. On the contrary, Brazil's Unified Health System has contributed to improved community health outcomes related to MCH, as over 98% of the required resources are channelled towards basic healthcare to attain universal health coverage [8].

The study has shown that most rural VHWs have larger geographical areas to cover and frequently have to walk over 5 km to access remote areas, as their bicycles are often deemed obsolete due to a lack of routine maintenance. These findings were also consistent with a systematic literature review by Astale et al. [7] on the challenges faced by CHWs in LMICs, who reported that a lack of transport had contributed to the perceived high workload, which hinders the efficiency of service delivery.

It was also reported that VHWs received US$42 per quarter, which they considered inadequate. They typically received it several months after the end of the quarter, which could be contributing to their waning motivation. These assertions were consistent with findings by Gore et al. [5] and Kambarami et al. [35] in Zimbabwe, who reported high attrition rates and a lack of enthusiasm, hindering the program's progress. Perhaps as a consequence of this, VHWs are highly recommended for providing adequate resources to support the effective delivery of PHC services.

Most respondents highly recommended using mobile health (mHealth) as a potential strategy to enhance primary health care (PHC) service delivery by village health workers (VHWs). While only a handful of these cadres reported having been issued mobile health technology gadgets, they seem to appreciate the need to catch up with advancements in mobile health technology. A scoping review by Early et al. (40) revealed an increasing number of health systems globally incorporating mHealth technologies and applications, with no exception for LMICs [40]. Whilst acknowledging the potentially disruptive nature of digital technology, the World Health Organisation maintained that these technologies could improve the skills and knowledge of Community Health Workers (CHWs) through data capture, storage, and exchange, as well as remote monitoring, virtual diagnosis, and facilitating a continuum of care throughout the healthcare system. Mobile health tools are now being explored worldwide to enhance the VHW's ability to effectively diagnose specific ailments, communicate and share electronic resources, and improve community health surveillance, geospatial mapping, and real-time reporting [41]. In India, the incorporation of the ReMind mHealth into the maternal and child health program helped to reduce maternal and neonatal deaths by over 300 and nearly 150,000 (respectively). The program contributed to women's empowerment, as mHealth tools facilitated effective engagement with Community Health Workers (CHWs) to identify maternal and child health (MCH) danger signs and manage them before conditions deteriorated [40]. In Malawi, an application known as cStock enables Health Surveillance Assistants (HSAs) to maintain optimal stocking levels. They interact with an ICT dashboard at the district level through an enquiry via a short message service (SMS) to receive updates on when to replenish their medical stocks [42]. On the other hand, a study in Kampala, Uganda, identified high training costs, skill deficiencies, and limitations in infrastructure and data security as potential barriers to the successful implementation of mHealth technologies for VHWs [43].

The integration of community health into the healthcare delivery system could improve the provision of essential health services by VHWs. Perhaps this was suggested to improve the working conditions for the VHWs, who are often regarded as volunteers despite the evolution of their roles and the shifting of tasks. In Zimbabwe and other sub-Saharan African countries, there is high staff attrition, and having VHWs integrated into the healthcare system could help bridge the human resources gap, ensure the program's sustainability, and improve knowledge and skills on best practices [44] Mupara et al. [45] made the point that community health integration entails their incorporation into healthy public policies and the six building blocks of the WHO’s framework on health systems. The Unified Health System of Brazil integrated CHWs, enabling improved working conditions, boosting a sense of identity within the healthcare system, and providing supportive supervision and enhanced mentorship, contributing to improved community health outcomes [46].

5. LIMITATIONS

This study was conducted in the Beitbridge district of Zimbabwe and could have implications for generalisation across the country. Furthermore, the self-reported data could also introduce some bias.

CONCLUSION

Village Health Workers in Beitbridge are predominantly female and appear to be literate. These complement the healthcare system through frequently conducting health education, community-based disease surveillance, and monitoring of infant growth rates. There is a high perception among the VHWs that they are inadequately resourced, with limited knowledge and skills, which could be contributing to the role of diagnosing and curing of minor ailments, practised the least, leading to more frequent referrals to health facilities. The VHWs felt they were given inadequate allowances, which could hinder their motivation. Given their contribution to community health, VHWs strongly prefer integration into the health system and the use of mobile health technology to enhance service delivery effectiveness and efficiency.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: O.M.: Is a PhD student in the Department of Public Health at the University of Venda who conceptualised the study; A.G.M.: Conducted data collection and analysis, and presented the findings in partial fulfilment of the degree requirements; N.S.M.: Supervised the concept development and verified data collection and analysis. As the co-supervisor, guided the study's conceptualisation and ensured quality control.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| CBS | = Community-Based Disease Surveillance |

| CHW | = Community Health Workers |

| COVID-19 | = Coronavirus Disease 2019 |

| ICT | = Information and Communication Technology |

| MEAL | = Monitoring, Evaluation and Learning |

| MRCZ | = Medical Research Council of Zimbabwe |

| MUAC | = Mid Upper-Arm Circumference |

| NGO | = Non-Governmental Organisation |

| PHC | = Primary Health Care |

| RDT | = Rapid Diagnostic Test |

| SDG | = Sustainable Development Goals |

| SPSS | = Statistical Package for Social Sciences |

| UHC | = Universal Health Coverage |

| VHW | = Village Health Workers |

| WHO | = World Health Organisation |

| TB | = Tuberculosis |

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

The University of Venda Research Ethics Committee (Registration FHS/23/PH/11/0709) and the Medical Research Council of Zimbabwe (MRCZ A/3175) ethically approved the study. The Permanent Secretary of the Ministry of Health and Child Care in Zimbabwe granted final authority, with the Beitbridge District Medical Officer's permission.

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of institutional and/or research committee and with the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki, as revised in 2013.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

Data will be made available by email upon request to the corresponding author.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Appreciation is extended to Lovinah and Emerge Ndou for their assistance with data collection and statistical analysis.