All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Alliance Model for Increasing Access to Sanitation and Improving Hygienic Practices in the Remote Community of Dhading District, Nepal

Abstract

Background

Access to adequate sanitation and hygiene is an important global health issue and remains a serious problem in Nepal.

Objective

This study aimed to apply the alliance model to manage a sanitation and hygiene project. The project sought to increase sanitation access and improve households’ basic knowledge of sanitation and hygiene, as well as the hygiene practices of household members, in Dhading District, a remote area of Nepal.

Methods

A mixed-method design was applied for data collection. The study sample included 18 alliance members and 492 household respondents. The alliance model consisted of three steps: (1) Preparation, including a situation assessment, formation of the alliance, and baseline measurement of study variables; (2) Action research using a one-group pre-test–post-test design to strengthen the management capacity of alliance members through planning, implementation, and evaluation of the sanitation and hygiene project; and (3) Reinforcement of capacity strengthening through a one-day review and reflection workshop with key alliance members and a final evaluation of post-alliance outcomes.

Results

Six months after implementing the model, the overall management capacity of alliance members increased significantly (p < 0.001). Households’ access to sanitation, basic knowledge of sanitation and hygiene, and hygiene practices also increased significantly (p < 0.001). The prevalence of diarrhea in the project area significantly decreased (p < 0.05) nine months after implementing the model.

Discussion

The model addressed key management issues within the alliance, fostered collaboration among major stakeholders, established a clear goal and action plan, mobilized resources, and secured the active participation of local residents in improving sanitation and hygiene in the Village Development Committee.

Conclusions

The model can be applied to strengthen alliance members' management capacity, thereby improving the effectiveness of rural sanitation and hygiene practices.

1. INTRODUCTION

People in Nepal have poor access to water, sanitation facilities, and materials for hygiene practices [1]. About 15% of households in the country lack toilet facilities (11% in urban areas and 21% in rural areas), and more than one million people practice open defecation [2, 3]. Around 20% of the population has no access to water, soap, or other materials for hand cleaning [2]. In 2022, only 16.12% of people in Nepal had access to clean water [4]. Several studies have found that drinking water is heavily contaminated with fecal matter [5-7]. Inadequate access to water, sanitation, and hygiene is a well-known risk factor for diarrheal diseases [8-10].

The people of Dhading District, one of the most underdeveloped and remote rural districts of Nepal, face poor access to sanitation and limited capacity to adopt proper hygienic practices. District sanitation statistics from 2011 show that 29% of the population does not use improved toilets [3]. Nearly 45% of the population belong to marginalized ethnic communities [11], which generally have poorer access to sanitation compared to the district average. The 2013 district health morbidity report, covering the previous five-year period, shows that three out of the ten most common diseases in the district are related to poor sanitation [12].

The “alliance” model of health promotion has been described as “collaborative working relationships of organizations and/or individuals that have a common purpose of enabling individuals or communities to increase control over and to improve their health” [13]. In Malawi, alliance models have been successfully applied for water management and sanitation, contributing to universal access and sustainability through partnerships among multiple stakeholders [14]. This approach has also been used in drinking water and sanitation projects in several other countries [15, 16].

In this study, the alliance model was implemented as a collaborative working framework at the community level in the Village Development Committee (VDC). It included representatives from government organizations, NGOs, community-based organizations, and individual community leaders, all working together on the agreed objectives of the sanitation and hygiene program. Shanti Nepal, an NGO, served as the lead agency, providing technical, financial, and human resource support to the alliance throughout the implementation of the model.

Strengthening the management capacity of alliance members is often essential in health projects aimed at achieving sustainable development goals on water supply, sanitation, and hygiene, including the elimination of open defecation [17]. Management capacity refers to competencies in planning, implementation, and evaluation of projects.

This study applied the alliance model to strengthen the management capacity of alliance members by launching a project to increase access to sanitation and improve the hygiene practices of household members in Thankre, a remote community in Dhading District, Nepal. The majority of the community members are poor and belong to marginalized or disadvantaged ethnic groups. The model also aimed to ensure the sustainability of the sanitation and hygiene project.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

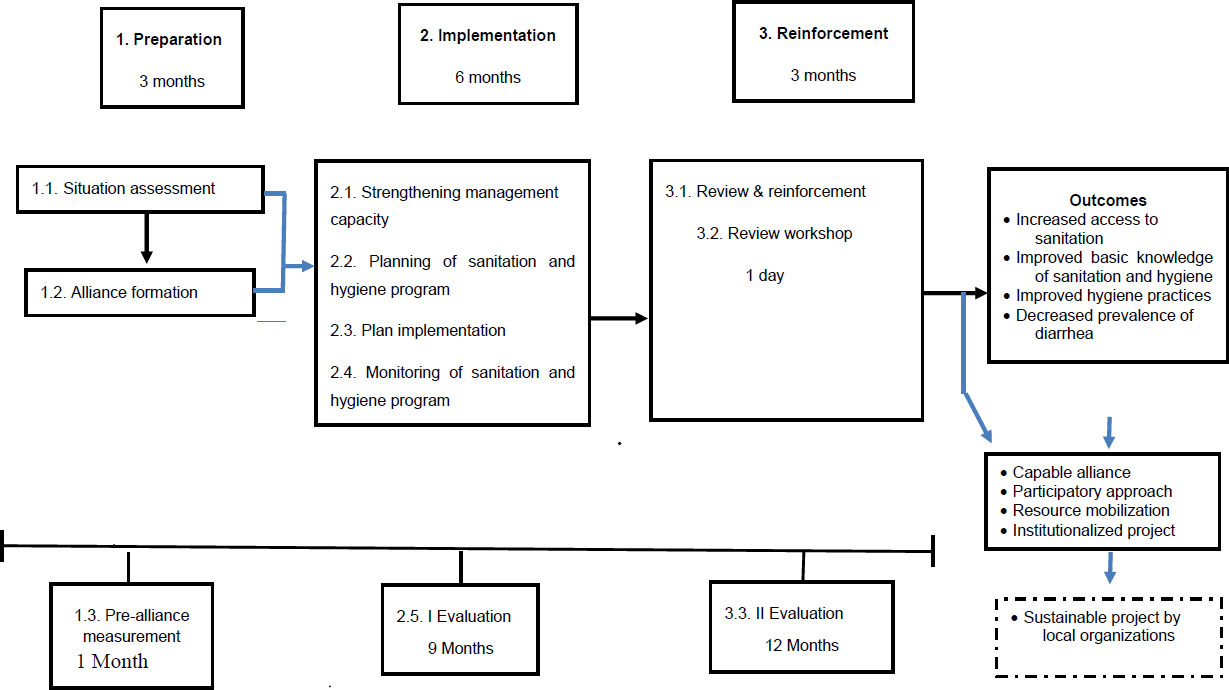

The conceptual framework of this study (Fig. 1) was based on Susman’s Action Research Process [18]. It comprised three steps: (1) Preparation, which included a situation assessment, formation of the alliance, and baseline measurement of study variables; (2) Action research, employing a one-group pre-test–post-test design [19] to strengthen the management capacity of alliance members through planning, implementation, and evaluation of the sanitation and hygiene project; and (3) Reinforcement of capacity strengthening through a one-day review and reflection workshop with key alliance members, followed by a final evaluation of post-alliance outcomes. Data were collected using a mixed-methods approach, as outlined in Table 1.

2.1. Study Population

The study was conducted in Thankre VDC, Dhading District, Nepal, a remote hilly area with altitudes ranging from lowlands to high hills. The term “Village Development Committee (VDC)” refers not only to the administrative committee but also to the area it governs. Thankre VDC comprises nine wards, which, at the time of the study, included a total of 2,141 households (9,838 people) [3]. According to the District Drinking Water and Sanitation Division Office (DWSO), toilet coverage in the VDC was estimated at 19.6%, the lowest in the region. In addition, nearly 45% of the VDC population belonged to various ethnic communities, including Tamangs, Chepangs, Dalits (scheduled castes), and others [11]. Thankre VDC was purposively selected from the 50 VDCs in Dhading District because it had the lowest sanitation coverage in the southern region, highlighting the highest need for improved access to sanitation and hygiene practices.

The conceptual framework of the proposed alliance model for increasing access to sanitation and hygienic practices.

| Step According to Susman’s Action Research Process | Activity/ Process | Data Collection from Alliance Members or Household Respondent Groups |

|---|---|---|

| Diagnosing the situation and identifying problems | Building rapport with key stakeholders to assess the sanitation and hygiene project. Identification of potential alliance members. Formation of an alliance. Pre-alliance measurement of study variables. | An observational checklist and self-assessment questionnaire were used to assess the management capacity of the eighteen alliance members, and a closed-ended interview questionnaire was used to assess household respondents’ basic knowledge of sanitation and hygiene. An informal interview was used to elicit the diarrhea prevalence of household members. |

| Planning action | Two workshops and one field visit for alliance members. | Sanitation and hygiene workshop & Management workshop, including planning, formulation of an action plan, and definition of the roles of alliance members. Exposure visits to a successful sanitation and hygiene project in Mauralibhanjyang VCD. |

| Taking action and collecting data | One sanitation and hygiene workshop for household members. | A closed-ended questionnaire was used to ask household respondents the same questions as the diagnosing the situation step. |

| Evaluating and studying the consequences of an action | Alliance periodically reviews the implemented project and evaluates it after implementation. | The final evaluates the level of access to sanitation and hygiene practices of the household respondents. Semi-structured interview with twenty-five key household respondents to probe some additional issues for improving the project. |

| Specifying learning- Identifying general findings | One-day review workshop for reviewing and identifying ways to improve the project. | Collecting the reviewed data and information from alliance members and the lead agency. |

The study population consisted of alliance members and household representatives. “Alliance member” refers to individuals representing local organizations or the community, selected by consensus within the alliance. These members included the VDC secretary, health post and sub-health post in-charges, NGO representatives working in the VDC, local school teachers, community leaders such as Female Community Health Volunteers (FCHVs), and local politicians. Alliance members were required to be at least 20 years old and willing to partici pate; those unable to read or write in Nepali were excluded.

“Household representative” refers to a male or female recognized by their household as the head or designated representative. Eligible participants were at least 18 years old, had lived in the community for more than six months, and were willing to participate. Exclusion criteria included inability to communicate verbally, temporary household membership, and age above 80 years.

2.2. Sample Size and Sampling

The total sample size was calculated using the formula for repeated measures [20]. Mean scores for access to sanitation and basic knowledge of sanitation and hygiene were obtained from a pilot study conducted in another VDC within the same district. It was projected that the intervention would lead to a 50% increase in the mean scores of these variables between baseline and post-intervention. The required sample size for a single group was calculated as 183 households. Since this study employed a pre-test–post-test design, the number was doubled. An additional 10% was added to account for potential household dropout, resulting in a final minimum required sample size of 402 households.

2.3. Quantitative Data Collection

The instruments used in this study were translated into Nepali and pre-tested with respondents from a nearby, similar household before data collection. Data were collected by the principal investigator and seven trained research assistants, all of whom had experience in community health and development work.

The pre-alliance self-assessment questionnaire for alliance members consisted of three parts. Part I included demographic information, such as sex, age, and educational level. Part II assessed basic knowledge of sanitation and hygiene and comprised 16 items with statements answered as “yes,” “no,” or “don’t know.” The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for this section was 0.690. Part III evaluated basic management competencies with 16 items, featuring a combination of response types, including single-response ordinal scale, multiple responses, and multiple-choice questions.

The closed-ended interview questionnaire for household respondents also comprised three parts. Part I contained seven items regarding general household and respondent characteristics, such as sex, age, and type of house. Part II included 23 items assessing basic knowledge of sanitation and hygiene. Respondents self-reported diarrhea symptoms in accordance with the WHO definition [21], with a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.682. Part III focused on hand-washing practices and diarrhea prevalence, containing four items with single and multiple-response formats.

The observational checklist had two parts. The checklist included yes/no or other related options for each item. Items were ticked after direct observation and/or confirmation by the household respondents.

Part I was on the availability and sanitary use of improved toilets and had 10 items. Part II was on practices related to the disposal of domestic waste and wastewater, disposal of domestic animal waste, and the safety of drinking water, and had 14 items with nominal scales. The total score for Part II was 14 for 14 items.

The total score for hygiene practices was calculated by summing the scores for basic knowledge of sanitation and hygiene, handwashing practices, household waste management, wastewater and domestic animal waste disposal, and the safety of drinking water at the point of use.

2.3.1. Workshops and Field Visits

Here’s a polished and consistent version of your list while keeping the content intact:

(1). A one-day workshop on sanitation and hygiene to provide alliance members with a basic understanding of sanitation and hygiene. The workshop was facilitated by the first author according to an organised schedule.

(2). A three-day workshop on project management for sanitation and hygiene, designed for alliance members to provide a basic understanding of management functions, followed by action planning for the first phase of the VDC sanitation and hygiene project.

(3). A one-day field visit to a successful sanitation and hygiene project, where alliance members reviewed and applied their learning to the project context.

(4). A one-day review workshop attended by alliance members and representatives from the lead agency to evaluate project activities and discuss lessons learned.

(5). A six-hour workshop for household members on sanitation and hygiene, focusing on basic knowledge and hygiene practices.

2.4. Qualitative Data Collection

For qualitative data, semi-structured interview guidelines were employed to interview eighteen alliance members to collect additional information on management competency and knowledge of sanitation and hygiene. Semi-structured interviews were also conducted with twenty-five key household informants, selected from the 492 household respondents, to gather supplementary data on access to sanitation, basic knowledge of sanitation and hygiene practices, prevalence of diarrhea, and other study variables. The semi-structured interviews with alliance members and household respondents were conducted by the principal investigator. Observation data were collected by the principal investigator and seven trained research assistants, all experienced in community health and development work.

2.5. Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarise all study variables and outcome measures. A paired t-test was applied to compare the management capacity of alliance members. Friedman's test was used to compare access to sanitation, basic knowledge of sanitation and hygiene, and hygiene practices among household respondents. In post-hoc analysis, Fisher's Least Significant Difference (LSD) test was used for pairwise comparisons to determine which ranges of access to sanitation, basic knowledge of sanitation and hygiene, and hygiene practices differed significantly. The chi-square test was employed to compare the prevalence of diarrhea before and nine months after the intervention. The significance level was set at α = 0.05. Qualitative data from semi-structured interviews and observations were analysed using content analysis and triangulation techniques.

2.6. Ethical Approval

This mixed-methods study, which combined qualitative research with a one-group pre-test–post-test design, received ethical approval from the Ethical Review Committee of the Faculty of Public Health, Mahidol University, Thailand (COA No. MUPH 2013-116), and the Nepal Health Research Council, Kathmandu, Nepal (Ref No. 2013-1469). Prior informed consent was obtained from all alliance members and household respondents aged 18 years and above after explaining the study objectives. Confidentiality of the data was strictly maintained. All research activities adhered to the approved protocol and the ethical guidelines of the Ethical Review Committee of the Faculty of Public Health, Mahidol University, Thailand.

3. RESULTS

3.1. The Conceptual Framework of the Proposed Alliance Model

The conceptual framework (Fig. 1) consisted of three steps.

Step 1: Preparation (three months)

1.1). Situation Assessment: Including identifying key stakeholders, such as representatives of local organizations, community group leaders, local schoolteachers, and local politicians.

1.2). Formation of the Alliance: Recruiting 18 members in the community to the alliance.

1.3): Baseline Measurement of the Study Variables: In the first month, a self-administered assessment questionnaire was used to assess the management capacity of the alliance members, and a semi-structured interview was conducted with four key alliance members to get qualitative data to complement the quantitative data. There was also a collection of household representative data regarding access to sanitation, basic knowledge of sanitation and hygiene, and hygiene practices. Prevalence of diarrhea from the 2012 Annual report, Department of Health Services [22]. In this study, diarrhea was defined as “the passage of 3 or more times of loose or liquid stools per day, or more frequently than normal for the individual” [21].

Step 2: Implementation (six months).

2.1) An Action Research Approach: The following activities were undertaken to strengthen the management capacity of the alliance members: 1) One-day workshop on sanitation and hygiene; 2) Two-day workshop on the management functions of the sanitation and hygiene project; 3) Action planning for the first phase of the project; 4) Exposure visit to Muralibhanjyang VDC in the same district to observe an a successful sanitation and hygiene project; 5) Visit review to apply learning to the project context; 6) Appreciative inquiry workshop to improve the motivation and positive thinking of the alliance.

2.2) Planning for the Sanitation and Hygiene Project. The planning workshop included: Analysis of the sanitation and hygiene situation in the VDC, stakeholders’ analysis, development of the project objectives and activities, formulation of an action plan, identification of resources, and definition of the roles of alliance members.

2.3) Implementation of the Sanitation and Hygiene Project: The key implementation roles the alliance played were: 1) Communication and coordination within the alliance and with the community; 2) Mobilization of FCHVs, sub-health post staff, and Ward Water Sanitation and Hygiene Coordination Committee for the sensitization of Mothers Groups; 3) Support for sanitation and hygiene awareness activities; 4) Organization of material and technical support to the households who built toilets; 5) Decision-making on important implementation issues; 6) Review of, reporting on, and monitoring of implementation; 7) Building of relationships with the District Drinking Water and Sanitation Division Office and the District Development Committee to obtain resources for the project.

2.4) Monitoring: The alliance periodically reviewed project implementation, conducted monitoring visits to communities, and submitted periodic progress reports to the Drinking Water and Sanitation Division Office and the alliance-facilitating organization.

2.5). Evaluation: After six months of implementation, the first evaluation of the study variables was done. The alliance made a decision for the evaluation. At this stage, the alliance also consolidated the lessons learnt from the alliance processes.

Step 3 Reinforcement (three months)

3.2. Review and Reinforcement

After six months of implementation, the project progress was reviewed. Following this review, the project placed greater focus on achieving Open Defecation Free (ODF) status in all nine wards of Thankre VDC within three to four months. This enhanced focus included: 1) continuing health awareness activities in community groups and schools; 2) frequent monitoring by the Ward Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene Coordination Committee; 3) providing material and technical support to households for toilet construction; 4) motivating households that had been resistant to the campaign; and 5) addressing key project management challenges, such as shortages of materials in the market.

3.3. Review Workshop

A one-day workshop, attended by alliance members and representatives from the lead agency, was conducted to review the project processes, assess project progress, identify strengths and weaknesses, and summarise lessons learned by the alliance.

3.4. Final Evaluation at Month 12

The final evaluation involved measuring the management capacity of the alliance members, households’ access to sanitation and hygiene, and the prevalence of diarrhea among household members. Semi-structured interviews were also conducted with 25 household representatives to explore additional issues related to sanitation and hygiene practices. Preliminary findings from the evaluation were shared during an alliance review meeting and used to identify strategies for improving the project in subsequent months.

3.5. Baseline Characteristics of Study Samples

3.5.1. Alliance Members

Of the 18 alliance members, 14 were male. The mean age was 40.7 years (SD ±10.9), ranging from 23 to 67 years. Approximately half (9/18) had completed primary or high school education, six were literate without formal schooling, and three had attained a bachelor's degree or higher.

3.5.2. Household Respondents

About 57% of the household respondents were female. The mean age was 41 years (SD ±16), with a range of 18 to 80 years. Around 38% were illiterate, and 17% had completed primary school. In terms of ethnicity, about 50% were Brahmin and 30% Chhetri. Approximately 75% were engaged in agriculture. Regarding housing, 81% lived in stone or brick houses, while 3% resided in temporary huts.

3.6. Management Capacity of the Alliance Members

Table 2 shows that six months after implementing the model, the overall mean score for management capacity of the alliance members increased significantly (p < 0.001). Both sub-domains, basic knowledge of sanitation and hygiene, and basic management function competencies, also showed significant improvement (p < 0.001).

Table 3 presents the changes in management capacity by level. The number of alliance members with a “high” level of management capacity increased from 4 at baseline to 10 after six months. No members remained at a “poor” level, and all members attained a “high” level of basic knowledge of sanitation and hygiene. Basic management function competencies increased from 1 member to 5 at a “high” level and from 11 to 13 at a “moderate” level.

3.7. Access to Sanitation, Basic Knowledge of Sanitation and Hygiene, and Hygiene Practices

Table 4 shows that six months after implementing the model, the overall median score for household access to sanitation increased significantly, from a baseline median of 0 (range 0–8) to a median of 7 (range 0–8) after nine months of implementation (p < 0.001). Similarly, basic knowledge of sanitation and hygiene improved significantly, from a total score of 14 (out of 22) at baseline to 19 after nine months (p < 0.001). Hygiene practice scores also increased significantly, from 7 (out of 19) at baseline to 11 after nine months (p < 0.001).

In post-hoc analysis, Fisher's Least Significant Difference (LSD) test was used for pairwise comparisons of access to sanitation, basic knowledge of sanitation and hygiene, and hygiene practices. Table 4 further shows that access to sanitation before implementation and after six months differed significantly (p < 0.001) from scores at nine months. Basic knowledge of sanitation and hygiene at baseline differed significantly (p < 0.001) from both six-month and nine-month scores, while the six-month score also differed from nine months (p < 0.001). Similarly, hygiene practices at baseline were significantly lower (p < 0.001) than at six and nine months, and scores at six months were also significantly different from those at nine months (p < 0.001).

| Variables | Before Alliance | After 6 Months | p* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Overall management capacity | 52.7 | 8.6 | 65.3 | 4.8 | <0.001 |

| Knowledge of sanitation and hygiene | 20.8 | 2.1 | 23.8 | 1.2 | <0.001 |

| Management competency | 31.9 | 7.7 | 41.5 | 4.1 | <0.001 |

Table 5 presents household access to sanitation and knowledge/practice levels. The proportion of households with “high” access to sanitation increased from 30.1% at baseline to 60.6% at nine months. Households with no access decreased from 55.7% at baseline to 27.2% at nine months. The proportion of household representatives with “good” basic knowledge of sanitation and hygiene rose from 0% at baseline to 75.0% at nine months, while those with “poor” knowledge decreased from 74.6% to 0.0%. Similarly, households with “poor” hygiene practices declined from 74.6% at baseline to 27.2% after nine months.

| Variables | Before Alliance | After Six Months | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Number | ||

| Overall management capacity | |||

| High | 4 | 10 | |

| Moderate | 13 | 8 | |

| Low | 1 | 0 | |

| Basic knowledge of sanitation and hygiene | |||

| Good | 15 | 18 | |

| Moderate | 3 | 0 | |

| Basic management function competency | |||

| High | 1 | 5 | |

| Moderate | 11 | 13 | |

| Low | 6 | 0 | |

| Variables | Total Score | Before Alliance | 6 Months | 9 Months | p * | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | R | M | R | M | R | |||

| Access sanitation | 8 | 0 a | 0-8 | 0 b | 0-8 | 7 a,b | 0-8 | < 0.001 |

| Basic knowledge | 22 | 14 a,c | 4-20 | 18 a,b | 10-22 | 19 b,c | 13-22 | < 0.001 |

| Hygienic practices | 19 | 7 a,c | 1-17 | 10 a,b | 3-18 | 11 b,c | 4-18 | < 0.001 |

a,b,c displayed paired different of each time point by Fisher's Least Square Difference (LSD) test.

| Variables | Before alliance | After 6 months | After 9 months | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Overall access | |||||||

| High | 148 | 30.1 | 165 | 33.5 | 298 | 60.6 | |

| Moderate | 66 | 13.4 | 55 | 11.2 | 56 | 11.4 | |

| Low | 4 | 0.8 | 6 | 1.2 | 4 | 0.8 | |

| No access | 274 | 55.7 | 267 | 54.3 | 134 | 27.2 | |

| Basic knowledge on sanitation and hygiene | |||||||

| Good | 2 | 0 | 254 | 51.6 | 369 | 75.0 | |

| Moderate | 123 | 25.0 | 237 | 48.2 | 123 | 25.0 | |

| Poor | 367 | 74.6 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Hygiene practices | |||||||

| Good | 2 | 0.4 | 9 | 1.8 | 11 | 2.2 | |

| Moderate | 123 | 25.0 | 280 | 56.9 | 347 | 70.5 | |

| Poor | 367 | 74.6 | 203 | 41.3 | 134 | 27.2 | |

Table 6 shows a significant decrease in the prevalence of diarrhea among children under five years of age after six and nine months of implementation (p < 0.05). Similarly, the prevalence of diarrhea among individuals aged five years and above also decreased significantly. Overall, the prevalence of diarrhea across all age groups decreased by 18.5% at six months and by 67.4% at nine months.

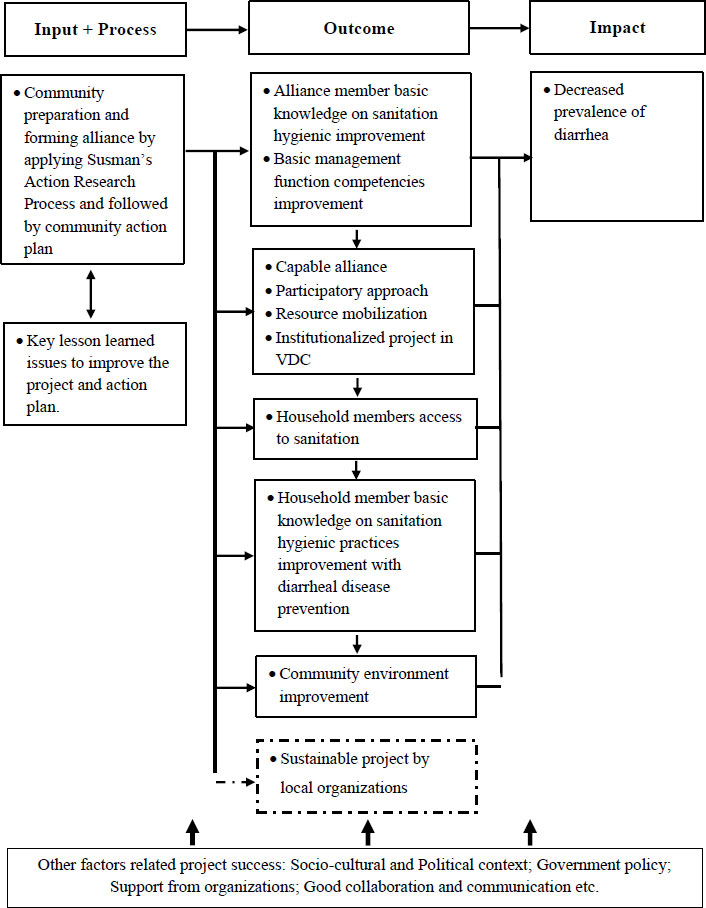

3.8. Summarized Alliance Model for Increasing Access to Sanitation and Hygienic Practices

The key lessons learned, along with other factors contributing to the success of the project, such as the socio-cultural and political context, government policies, and support from organizations, can be used to improve future sanitation and hygiene projects and action plans (Fig. 2) [23]. The alliance model may also be applied in other developing areas or countries.

Summarized alliance model for increasing access to sanitation and hygienic practices (modified from Kitphati et al., 2022 [24].

| Age group |

Before n |

P/100 |

6 Months n |

P/100 |

% change n (%) |

9 Months n |

P/100 |

% Change n (%) |

P* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <5 years | 25 | NA | 36 | NA | +11(+44.0) | 7 | NA | -18(-72.0) | 0.034 |

| 5 years + | 67 | NA | 39 | NA | -28(-41.8) | 23 | NA | -44(-65.7) | <0.001 |

| Overall | 92 | 2.5 | 75 | 2.1 | -17(-18.5) | 30 | 0.8 | -62(-67.4) | <0.001 |

4. DISCUSSION

In this study, the alliance model aimed to increase access to sanitation and improve hygienic practices among poor and marginalised people in remote areas, considering their original lifestyle and specific contexts, since there were significant population differences between rural and urban residents, as well as between rich and poor residents [24]. Therefore, the alliance model applied Susman’s Action Research Process concept to diagnose community sanitation and hygiene problems of household members before forming the alliance. The model was applied to address the multi-dimensional and multi-sectoral issues related to the management of sanitation and hygiene projects in the local VDC context. The study was conducted in Thankre VDC, which had one of the poorest sanitation and hygiene situations in the district [25], and the regular sanitation program approach was not effective in achieving the objectives.

The alliance model in this study was implemented in a challenging socio-political and cultural context to improve sanitation and hygiene management. At that time, there was no strong or organized administrative structure at the VDC due to the absence of an elected government for over a decade. The formation and implementation of the model began in an unstable and sensitive socio-political environment, just a few months before the national election, with community members divided based on their affiliations to different political parties. The socio-economic and cultural diversity of the communities also posed challenges. The alliance model has been adapted across various sectors, contexts, structural levels, and among different types of stakeholders.

Another hindrance to the project was an earthquake in the study area around four months after data collection, which caused the destruction of toilets and other sanitation and hygiene structures, reducing access to drinking water and sanitation facilities. The community had to rebuild the toilets and other facilities. As a result, the Ward and VDC WASH Committees could not declare the community an Open Defecation Free Zone as planned in the workshop.

4.1. Strengths and Limitations of the Study

The capacity building intervention was useful and exciting part of the project that made alliance members actively involved in the sanitation and hygiene project. In addition, their continuous involvement in planning, implementing, and monitoring of the project contributed to improving their management capacity. The clearly defined common goal and action plan gave them a direction and framework for involvement, which was helpful to unite them. The alliance was formed with the leadership of the VDC secretary who was the acting chair for the VDC which was the local government authority to oversee the development and administrative functions. The alliance was able to mobilize a large number of resources from different stakeholders. The alliance was effective in building a good level of trust among the project stakeholders which was lacking at the beginning due to the socio-political and cultural context of the VDC.

Our findings are similar to a report from a study in two districts in northern Karnataka, India [26], which improved the capacity of the Village Health and Sanitation Committee (VHSC), a local body involving stakeholders for planning and monitoring health and sanitation activities. Evaluation of the two-year program outcomes showed significant improvements in members' participation, provider-community interactions, and VHSC meetings. The action research intervention in our study increased the effectiveness of alliance members in implementing, managing, and sustaining the sanitation and hygiene project.

The current study has some limitations. The purposive selection of Thankre VDC, due to its lowest sanitation coverage, may introduce selection bias. Future research should involve a larger number of participants and include a control group to establish stronger evidence. In addition, the validity and reliability of diarrhea prevalence also rely on self-reports from household respondents and information from the Department of Health Services of Nepal. However, diarrhea is a common disease, and most household respondents were familiar with its symptoms, so this may cause only minor errors.

The decrease in diarrhea cases among children under 5 years was marginally significant. However, there were highly significant decreases in diarrhea for the overall population and for individuals above 5 years of age. Possible explanations include the fact that early childhood diarrhea is caused by multiple factors, such as children’s nutritional status, access to water and sanitation [9], caregivers’ hygiene practices [27, 28], and climate factors [29]. From the household survey, we found that several poorer households lacked soap, coal ash, or other local cleaning agents for handwashing, could not afford a water purification system, and kept domestic animals at home. These factors can contribute to childhood diarrhea. A study in Laos PDR [28] found that children in households with handwashing facilities, including both water and soap, were less likely to contract diarrhea compared to households with water alone. Adults may improve their hygienic practices more effectively after a behavior change campaign than children under 5 years, which may explain the higher number of diarrhea cases in this age group.

4.2. Sustainability of the Sanitation and Hygiene Project

Sustainability is a broad concept, and its definition and indicators depend on which aspects of sustainability are being focused on [17]. Various concepts of sustainability exist from different perspectives, focusing on the environment, communities, or project planning [30-33]. In this study, sustainability refers to the long-term expected impact on the management of the sanitation and hygiene project as a result of applying the healthy alliance. Several key indicators were identified at the end of the study that may contribute to the project’s sustainability.

4.3. Capacity of the Alliance

There was a functional alliance under the leadership of the VDC Secretary at the VDC. The study showed that their project management capacity had improved significantly. They had clearly defined project goals and basic management capacity to prepare the next phase plan involving all stakeholders. They also demonstrated competencies in fundamental management functions. A capable alliance has greater potential to continue the project in the future.

4.4. Participatory Approach

The alliance implemented the project by involving all stakeholders and community members. Every sector of the community participated in the project in different ways, creating momentum for the initiative. This participatory approach has been established as part of the project.

4.5. Resource Mobilization

The alliance was able to mobilize a large number of resources, including funds from different stakeholders. Partnerships and networks were established with key stakeholders, and local resources were effectively mobilized. Therefore, the alliance now has the network, capacity, and experience to secure the resources required to continue the project in the future.

4.6. Institutionalized Project in the VDC

According to government policy, the local VDC is responsible for leading sanitation and hygiene projects. The alliance was established under the leadership of the VDC, and all project plans were submitted to the VDC Council, the supreme body responsible for policy formation and budget allocation. The VDC has prioritised the sanitation and hygiene project, allocating increased budgets over the last two years, making it a regular and prioritized part of the VDC’s activities.

These key indicators suggest that the sanitation and hygiene project has potential for future sustainability and for achieving its goals and objectives.

CONCLUSION

The model was effective in strengthening the management capacity of alliance members, which led to more effective project management. The intervention addressed key management issues within the alliance, fostered collaboration among stakeholders, established a clear goal and action plan, mobilized resources, and ensured the active participation of local people in improving sanitation and hygiene in the VDC. As a result of the capacity-building intervention and the alliance model, the sanitation and hygiene project achieved the desired outcomes in terms of access to sanitation, knowledge of sanitation and hygiene, adoption of hygiene practices, and ultimately, a decreased prevalence of diarrhea in the remote community. Therefore, agencies implementing health alliances should consider strengthening management capacity as a critical first step after formation and maintain it as a continuous process.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: K.M.S., N.S., M.T. and N.H. Designed the study; K.M.S.: Conducted the data collection; K.M.S. and M.T.: Analysed the data; K.M.S., N.S., N.H. and M.T. Interpreted the findings and drafted and revised the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final version.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| VDC | = Village Development Committee |

| NGOs | = non-government organizations |

| DWSO | = District Drinking Water and Sanitation Division Office |

| FCHV | = Female Community Health Volunteers |

| VHSC | = Village Health and Sanitation Committee |

| WASHCCs | = Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene Coordinating Committees |

ETHICS APPROVAL PARTICIPATE AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

This study received ethical approval from the Ethical Review Committee of the Faculty of Public Health, Mahidol University, Thailand (COA No. MUPH 2013-116), and from the Nepal Health Research Council, Kathmandu, Nepal (Ref No. 2013-1469).

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

No animals were used in this research. All human research procedures were conducted in accordance with our protocol and the Ethical Review Committee of the Faculty of Public Health, Mahidol University. The study adhered to the ethical guidelines of the 2013 revision of the Declaration of Helsinki (1975).

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Verbal consent was obtained from each participant before participating in the study.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

The data and supportive information are available within the article.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors sincerely express their gratitude to the Finnish Evangelical Lutheran Mission and deeply appreciate the organization Shanti Nepal for providing the opportunity and support to undertake this course. The authors would also like to thank Thakre VDC, all members of the alliance, and the Ward Water Sanitation and Hygiene Coordinating Committees (WASHCCs) for their cooperation in conducting the research project.