All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

The Effectiveness of Psychoeducation based on Social Support to Improve the Psychological Well-being of Stunted Adolescents

Abstract

Introduction

Unaddressed cases of stunting in childhood will affect future development, including adolescence. Adolescents who have a shorter height tend to get unfavorable treatment, which can affect their psychological well-being. One factor that can improve it is social support from family and peers. Researchers have developed a social support-based psychoeducation module to improve psychological well-being in stunted adolescents. This study aims to assess the effectiveness of psychoeducation in improving psychological well-being in stunted adolescents.

Materials and Methods

This research used a quasi-experiment with a pretest-posttest control group design. The research subjects consisted of 30 students from SMK PP Padang Mengatas, who were selected using purposive sampling, and were divided into an experimental group of 17 participants and a control group of 13 participants. Data were obtained using the Ryff Psychological Well-Being Scale and the Social Provision Scale, both of which had been modified by the researcher.

Results

The paired sample t-test results showed that the social support-based psychoeducation had a significant effect on stunted adolescents (p = 0.003; p < 0.05). The effect of treatment was proven to be significant, indicating an increase in the subject's psychological well-being who received social support-based psychoeducation.

Discussion

The provision of psychoeducation involving groups is considered appropriate for improving psychological well-being. In addition, providing social support-based tasks can help train adolescents to improve their psychological well-being across various dimensions.

Conclusion

Furthermore, this psychoeducation module can be an alternative to improve psychological well-being in adolescents.

1. INTRODUCTION

Indonesia continues to face widespread stunting. Data from the Indonesian Ministry of Health, based on the 2021 Indonesian Nutrition Status Survey (SSGI), reported that 24.4% of children under five were stunted. The provinces with the highest prevalence were East Nusa Tenggara (37.8%), West Sulawesi (33.8%), Aceh (33.2%), West Nusa Tenggara (31.4%), and Southeast Sulawesi (30.2%) [1]. In West Sumatra Province, the prevalence increased from 23.3% in 2021 to 25.2% in 2022, exceeding the WHO threshold of 15–20% (Anugrah & Qonita, 2021). West Sumatra ranks 14th nationally, with six districts above the provincial average: West Pasaman, Mentawai Islands, South Solok, Sijunjung, Pesisir Selatan, and Pasaman [2].

Stunting is a manifestation of growth faltering caused by prolonged nutritional deficiencies, typically from pregnancy until the first 24 months of life [3]. The WHO defines stunting as height-for-age more than two standard deviations below the international reference median [4]. Other scholars describe it as a growth problem linked to malnutrition and protein deficiency in children [5]. Beyond inadequate nutrition in children and pregnant women, stunting is also influenced by multidimensional factors such as poor parenting [6], limited access to health services, insufficient nutritious food, and lack of clean water [7, 8].

Stunting can begin as early as the second trimester of pregnancy and may result in impaired skeletal growth [9]. If left unresolved, childhood stunting carries consequences into adolescence and adulthood (Bharali et al., 2019; Soliman et al., 2021). Stunted adolescents often experience delayed growth, developmental impairments, poor cognitive functioning, and increased morbidity and mortality [9]. Malnutrition can hinder brain development, contributing to poor academic achievement and lower cognitive test scores [10-12].

In addition to physical and cognitive consequences, stunted adolescents are at heightened risk for psychosocial problems. They may experience internalizing symptoms (e.g., depression, withdrawal), externalizing behaviors, and attention difficulties [13]. Short stature outside perceived “ideal” body standards often exposes them to bullying, low self-efficacy, and difficulties in peer interaction [14]. Previous studies have also linked stunting to low self-esteem and family problems [15]. Low self-esteem reduces adolescents’ ability to maintain positive self-regard, especially when facing negative evaluations from others [16].

Psychological well-being, as conceptualized by a previous study [17], refers to optimal functioning across six dimensions: self-acceptance, positive relationships, autonomy, environmental mastery, purpose in life, and personal growth. It involves accepting strengths and weaknesses, establishing healthy social relationships, adapting to environmental demands, and maintaining a sense of meaning and purpose [18]. For adolescents, psychological well-being is crucial for emotional regulation, resilience, and successful transition to adulthood.

Among the key predictors of psychological well-being is social support [19, 20]. Perceived social support has been shown to influence well-being indirectly through self-esteem [21]. Social support encompasses emotional, informational, and instrumental assistance from trusted networks of family, peers, and teachers [22, 23]. Such support not only buffers stress but also promotes adaptability, prosocial behavior, and higher subjective well-being [24, 25].

While previous research has established a link between social support and adolescent psychological well-being, few studies have focused on stunted adolescents, who may face greater psychosocial challenges than their peers. Addressing this gap, the present study investigates the effectiveness of a social support-based psychoeducation program in enhancing the psychological well-being of stunted adolescents at SMK PP Padang Mengatas, Indonesia.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study involved 30 adolescents enrolled at SMK PP Padang Mengatas, with 13 assigned to the control group and 17 to the experimental group. The participants consisted of 18 males and 12 females. The inclusion criteria required participants to be male or female adolescents aged 11–18 years, with a height below 155 cm (5 ft) for males and below 149 cm (4.8 ft) for females, identified as adolescents indicated to be stunted, and willing to participate in the full series of intervention activities. The exclusion criteria included adolescents with chronic or severe medical conditions unrelated to stunting, those with diagnosed psychiatric disorders requiring clinical treatment, and participants who were unable to complete the intervention sessions. Additionally, adolescents whose guardians did not provide informed consent were excluded from the study.

Participants were recruited using purposive sampling to ensure they met the predetermined criteria. The relatively modest sample size reflects the intensive and structured nature of the intervention, which required participants’ availability and sustained commitment to complete the program. The independent variable was social support, while the dependent variable was psychological well-being. A quantitative approach was employed using a quasi-experimental design with a pretest-posttest control group [26]. The overall research design applied in this study is presented in Table 1.

| Group | - | Pre-test | Treatment | Post-test |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experiment | Random | O1 | X | O2 |

| Control | Random | O1 | - | O2 |

This study did not seek formal ethical approval from an institutional review board, as it was conducted within a school-based educational program considered to pose minimal risk. Nonetheless, all procedures adhered strictly to ethical principles for research involving human participants. Participation was voluntary, and written informed consent was obtained from the legal guardians of all adolescent participants prior to data collection, along with assent from the adolescents themselves. Confidentiality and participant anonymity were maintained throughout the study.

3. EXPERIMENTAL

In the experimental group, the first measurement (pretest) was conducted prior to the intervention, followed by a second measurement (posttest) after the intervention. The treatment consisted of psychoeducation and training sessions delivered over two weeks. The control group completed the pretest and posttest assessments without receiving the intervention.

Psychological well-being was measured using a modified version of Ryff’s Psychological Well-Being Scale [17], which contained 41 items. Content validity was assessed through expert judgment, and the instrument demonstrated high internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.923. Social support was measured using a modified Social Provision Scale [27] comprising 22 items. Content validity was also confirmed through expert review, and the instrument demonstrated high reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.900). The detailed steps of the psychoeducation program based on social support are outlined in Table 2.

Data were analyzed using both descriptive and inferential statistics. The paired-samples t-test, conducted with SPSS version 25, was used to examine differences in psychological well-being scores between the pretest and posttest. A p-value of <0.05 indicated a statistically significant difference. Prior to the t-test, data normality was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. A significance value greater than 0.05 (p > 0.05) indicated normally distributed data, while a value less than 0.05 (p < 0.05) indicated a non-normal distribution.

4. RESULTS

4.1. Descriptive Analysis

The descriptive analysis provides an overview of psychological well-being scores at pretest and posttest for both groups. The results, including mean values and standard deviations, are summarized in Table 3, which presents the comparative differences between the experimental and control groups.

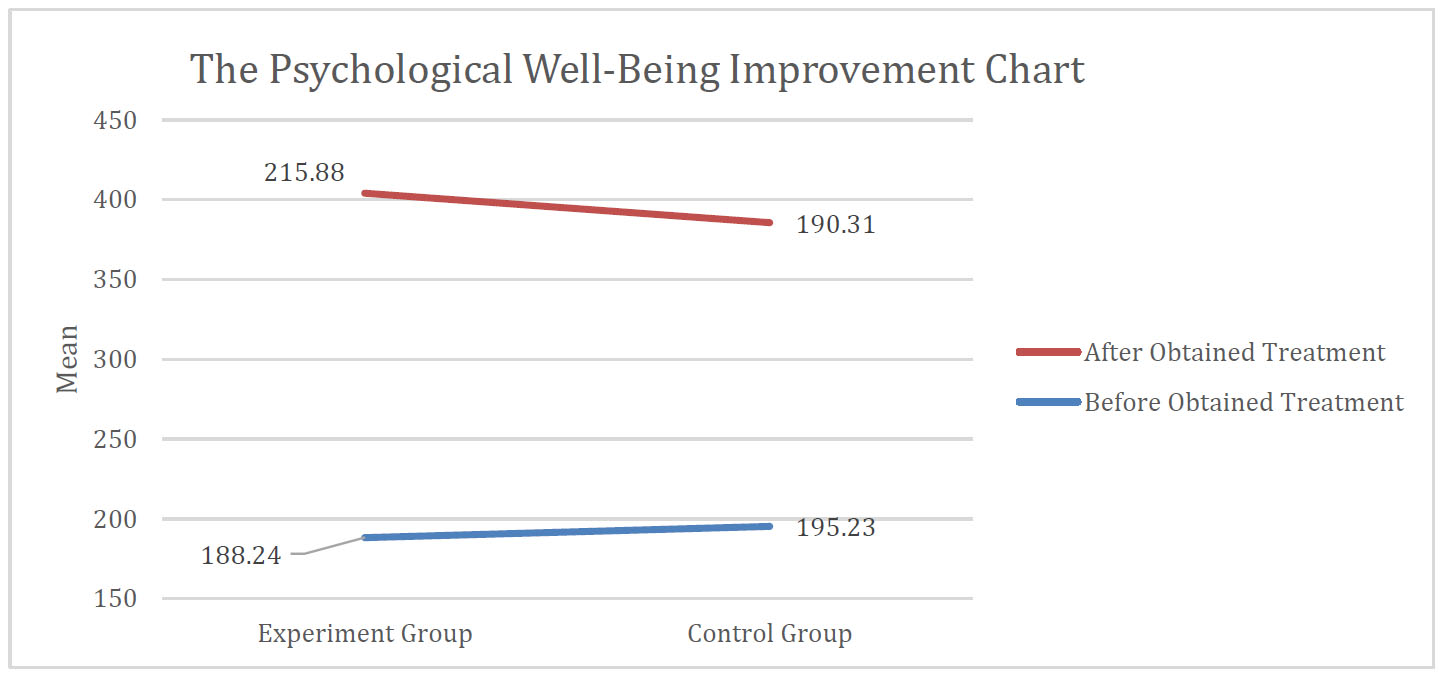

The psychological well-being results are presented in two stages: the initial measurement (O1) and the post-intervention measurement (O2). At the pretest, the experimental group had a lower mean score (188.24) than the control group (195.23). At posttest, the control group, which did not receive the intervention, showed a decline in mean psychological well-being to 190.31, whereas the experimental group demonstrated an increase to 215.88. In terms of change from baseline, the control group decreased by 4.92 points, while the experimental group improved by 27.64 points, indicating a substantial effect of the intervention (Fig. 1).

| Step | Main Activity |

|---|---|

| Step 1. Introduction and pre-test | Participants were introduced to the program and completed baseline measures of psychological well-being and social support. |

| Step 2. Self Acceptance | Participants explored physical, psychological, and social aspects of self-acceptance using the Johari Window. |

| Step 3. Relationships with others | Participants learned the value of positive relationships through cooperative group games. |

| Step 4. Autonomy | Participants engaged in the “Tree of Hope” activity to develop decision-making skills and future planning. |

| Step 5. Environmental mastery | Participants analyzed case studies using a contextualized teaching and learning (CTL) approach to improve problem-solving. |

| Step 6. Purpose in life | Participants analyzed case studies using a Contextualized Teaching and Learning (CTL) approach to improve problem-solving. |

| Step 7. Personal growth | Participants undertook a 40-day self-improvement challenge to enhance personal potential and quality of life. |

| Step 8. Evaluation and post-test | Participants evaluated the program and completed post-intervention measures. |

| Groups | n | Mean | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Test | - | - | - |

| Control Group | 13 | 195.23 | 24.345 |

| Experiment Group | 17 | 188.24 | 18.054 |

| Post-Test | - | - | - |

| Control Group | 13 | 190.31 | 19.315 |

| Experiment Group | 17 | 215.88 | 35.206 |

Improvement in psychological well-being scores between pretest and posttest for the control and experimental groups.

4.2. Normality Test

The normality of the data was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test in SPSS version 25. A significance value greater than 0.05 (p > 0.05) indicates normally distributed data, while values below 0.05 (p < 0.05) indicate non-normal distribution. The results of the Shapiro-Wilk normality test for psychological well-being scores are shown in Table 4.

| Groups | Shapiro-Wilk | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Statistics | N | p-value | |

| Pre-Test | - | - | - |

| Control group | 0.920 | 13 | 0.252 |

| Experiment group | 0.957 | 17 | 0.575 |

| Post-Test | - | - | - |

| Control group | 0.888 | 13 | 0.092 |

| Experiment group | 0.897 | 17 | 0.061 |

The results show that all p-values were greater than 0.05, confirming that the psychological well-being data in both groups at pretest and posttest were normally distributed. Therefore, the assumptions required for parametric testing were met.

4.3. Paired Sample T-Test

To test the research hypothesis, a paired-samples t-test was conducted in SPSS version 25 to compare pretest and posttest scores within groups. This test was selected because the data met the assumption of normality. A significance value of less than 0.05 (p < 0.05) indicates a statistically significant difference between the two measurements. The results of the paired sample t-test comparing pretest and posttest scores are presented in Table 5.

| Comparison | Sig. (2-tailed) |

|---|---|

| Pretest-Posttest | 0.003 |

As shown in Table 5, the significance value for the pretest-posttest comparison was 0.003, which is below the 0.05 threshold. This finding indicates a significant improvement in psychological well-being following the social support–based psychoeducation intervention.

5. DISCUSSION

Based on the results of the research, this research hypothesis is proven. The psychoeducation based on social support can effectively improve the psychological well-being of stunted adolescents. Several previous studies have also discussed ways to improve psychological well-being. Folk-Williams revealed that well-being therapy is a psychological treatment that strives to assist individuals by increasing their positive aspects and developing their strengths without emphasizing their negative aspects [28]. In the positive psychology approach, interventions for existing problems do not only focus on overcoming and eliminating the symptoms and the causes of problems, but also on improving well-being. Another study shows the benefit of group therapy as one of the successful interventions in improving the psychological well-being of the participants. Group therapy aims to solve emotional difficulties, build the character, and enhance the personal meaningfulness of the participants in the group. Fava and Ruini explained that by directly targeting interventions on the dimensions of well-being, the problems may indirectly be resolved, and the individuals are able to achieve psychological prosperity [29].

The first aspect of psychological well-being is self-acceptance. Individuals with good self-acceptance have a positive attitude towards themselves, recognize and accept both positive and negative traits, and view the past positively. However, individuals with poor self-acceptance feel dissatisfied with themselves and are often disappointed with their past [30]. Grinder explains that there are three aspects of self-acceptance: physical, psychological, and social.

The physical aspect relates to an individual's satisfaction with their body and physical appearance, reflecting their evaluation and self-assessment of how pleasant and satisfying their appearance is [31]. The view of the ideal body, which is attached to a certain culture, influences how positively or negatively adolescents perceive their appearance. The ideal body for adolescent girls is often perceived as tall and slim, while the ideal body for boys is a muscular body with a slim waist and hips. Negative body image may affect life satisfaction [32]. Several studies show that physical appearance is related to weight, height, skin color, and overall appearance. It is also associated with satisfaction or dissatisfaction with the body and self-esteem in adolescents, especially adolescent girls [33]. According to a previous study (Walker 2007), stunted adolescents are more likely to exhibit symptoms of anxiety, depression, and low self-esteem than normal adolescents. They frequently experience sadness, withdraw from social interactions, feel isolated among their peers, and have low self-esteem, which may lead to being teased by others [15]. When stunted adolescents find themselves in a new environment with unfamiliar people, they often experience feelings of sadness, embarrassment, inferiority, annoyance, and a sense of being different from others. It is common for stunted adolescents to cry due to bullying from their peers and juniors. Some of them often engage in daydreaming as a way to escape the teasing they receive from their peers. Additionally, stunted adolescents who are victims of bullying are more likely to experience anxiety, post-traumatic stress, depression, and in severe cases, suicide [34].

Psychoeducation was used to increase self-acceptance in stunted adolescents through the Johari Window. The Johari Window is a simple tool for illustrating and increasing self-awareness among individuals in a particular group. The main benefit of this psychological model is to help individuals better understand their mental state through a series of self-assessments and assessments from others. It is also effective in enhancing understanding and self-awareness [35]. In its implementation, participants give and receive feedback—whether in the form of information, praise, or criticism from others—for the purpose of developing their personality [36]. This may also include receiving feedback as part of the social support provided.

The second aspect of psychological well-being is relationships with others. One important component of mental health is having positive relationships with others. Self-actualization plays an important role in building good relationships with others through strengths such as empathy and compassion for others, the ability to love more deeply, close friendships, and deeper knowledge of others [30]. One of the benefits of establishing a positive relationship with others is receiving social support. Smet divided social support into four dimensions. They are emotional support, which includes expressions of empathy and caring for others; appreciation support, in the form of appreciating others; instrumental support, which provides assistance to others; and informational support, which provides advice, instructions, suggestions, and feedback [22]. Social support provided by close others can relieve negative emotions, help individuals feel that they are not alone and have companions in coping with difficulties, and provide motivation to overcome distress. The psychoeducational intervention aimed at enhancing positive interpersonal relationships was delivered through group cooperation games. These games involve collaborative activities where individuals work together to achieve shared goals [37]. Participation in such games facilitates the development of essential social competencies, including sharing, conflict resolution, and maintaining and fostering healthy relationships [38]. Moreover, group games have been shown to improve communication, social interaction, idea exchange, decision-making, active listening, and the willingness to engage in personal growth. These abilities are transferable to everyday life and can help individuals prepare for meaningful participation in society. The enhancement of communication and interpersonal skills, particularly the capacity to share ideas, listen actively, and strive for self-improvement, is closely linked to the development of social support networks.

The third aspect of psychological well-being is autonomy. Autonomy is the ability to determine one's own destiny, be independent, and regulate one's behavior from within. A person is said to have good autonomy if they are brave, able to make decisions independently, and think before acting. Meanwhile, someone with low autonomy is often worried about others’ opinions and is not confident in making decisions [30]. Several previous studies have found that stunted adolescents are more vulnerable to experience depressive symptoms, have lower self-esteem, and have higher levels of anxiety than adolescents in general. This is due to the bullying and mistreatment they receive. This could affect their decision-making skills. Stunted adolescents have less freedom and depend on the judgment of others when making decisions [39]. Family is the first and main pillar in shaping the children to be independent [40]. The greatest support at home, or in the domestic environment, comes from parents. Parents are expected to provide opportunities for their children to develop their abilities, take initiative, make decisions about what they want to do, and be responsible for their actions. Fischer states that one factor that plays an important role in cultivating independence in students is the support they receive from the community in which they belong, such as schools, friends, parents, teachers, and others [41].

Psychoeducation could increase autonomy through the Tree of Hope by helping people make choices in future planning, such as goals, desires, achievement strategies, and more. The function of the Tree of Hope is to develop individuals' personalities so they are more directed and aligned with their interests, enabling them to achieve short- and long-term plans. The general purpose of the Tree of Hope is to assist individuals in understanding themselves and their environment in decision making, planning, directing decisions on planning, and directing activities that lead to careers and hopes, and the ways of life that will provide a sense of satisfaction due to suitability, harmony, and balance with themselves and the environment where they belong. Adolescents who already have a vision of their future and the courage to express their ambitions will be more motivated to be diligent and more committed to realizing their goals [42]. In the context of this study, the participants may consider information and advice from others before planning for the future. This is part of social support.

The fourth aspect of psychological well-being is environmental mastery. Environmental mastery is the ability to manage the environment we are in and use it effectively to achieve our goals [17]. In short, individuals can face and control events outside themselves, allowing them to freely fulfill the needs and demands of life. Environmental mastery is a sign of individual mental health, evident in their ability to choose and create their psychological state and to control a complex environment. Therefore, they can take advantage of opportunities and benefit from their environment [30]. Stunted adolescents often suffer negative stigma from their social environment. As a result, they tend to have problems in social adaptation [34]. Problems in social adaptation prevent adolescents from mastering or surviving environmental changes in their lives.

The psychoeducation program used to improve environmental mastery was conducted through case studies. Utami recommends the case study method as an implementation of a Contextualized Teaching and Learning (CTL) approach because it narrows the gap between theory and practice [43]. Anggraeni states that to enhance an individual’s abilities beyond lecturing and explanation, efforts are needed to train and practice the skills they have. One of these efforts is developing the habit of analyzing and finding solutions to problems through the case study method. The case study method is used to develop critical thinking and to find new solutions to the problems being addressed. In practice, the solutions that the participants offer are discussed in small groups. A group discussion is one of the strategies used in learning methods, as it actively involves participants in discussing and finding alternative solutions to a topic considered problematic [44]. Furthermore, discussion teaches participants cooperation and collaboration [45]. This is related to social support.

The fifth aspect of psychological well-being is purpose in life. Purpose in life serves as a guide for individuals in living their lives. It is useful for guiding behavior, forming ideals, and finding meaning in life. In addition, it can help with decision-making on both small and large scales [17]. Individuals with good mental health have a clear understanding of the purpose and meaning of life, as well as a sense of order and intentionality in living their lives. A person with a clear purpose in life has goals, intentions, and direction, which contribute to a feeling that their life is meaningful. In contrast, individuals with a lower sense of purpose in life feel that their lives are not meaningful, have few goals or objectives, lack direction, and have no views or beliefs that give meaning to their lives [30]. Height affects many aspects of life. On average, stunted children experience a decrease in Intelligence Quotient (IQ), and malnutrition during the first year of life can result in lifelong cognitive impairment [46]– [49]. Research shows that cognitive decline due to stunting is caused by low protein intake [10, 50]. Essential amino acid levels in stunted children are lower than in children who are not stunted. Low levels of amino acids in the blood can impair a child's growth. Amino acids are crucial for protein synthesis and for activating the mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1), which plays an important role in myelination and the growth of various tissues [48, 51]. In stunted individuals, learning achievement tends to be low, and they may not be able to continue their studies [34]. In contrast, taller individuals are more likely to have high-status jobs and earn more than other workers [52]. Taller adolescents are considered to have faster cognitive development. According to Guo et al., adolescents' height can indicate their cognitive aptitude, with taller individuals having greater cognitive capacities. The findings of this study indicate that adolescents' cognitive capacities are influenced by their developmental pace. The cognitive capacities of adolescents who reach puberty earlier are higher. Individuals who begin their development early typically have a higher height during adolescence, indicating higher cognitive capacities. This is because height reflects the stage at which an individual begins a developmental phase [53]. This is supported by the research of Tran et al., which shows that short adolescents have lower Wide Range Achievement Test (WRAT) scores than normal adolescents with learning difficulties. Such a stereotype affects the selection of jobs for adolescents who are short, as they may feel insecure about their height, and consequently, their job choices are limited [54]. This limitation may negatively affect the sense of purpose in life for stunted adolescents.

There are various ways to increase the dimension of purpose in life. One of them is by doing self-reflection through writing notes (journaling). The journaling technique was adopted from Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy (REBT), a counseling technique pioneered by Albert Ellis. Bradley explained that journaling can be used for self-discovery, growth, and self-actualization by channeling feelings and emotions through creative expression and the writing process [55]. The benefits of writing include relieving stress, serving as a medium for planning and achieving goals, acting as a reminder of commitment, monitoring progress, formulating new ideas, storing inspiration, preserving memories, providing an alternative approach to problem-solving, and serving as a tool for reflection and wisdom. In practice, the friends' dimension of perceived social support contributes to the purpose-in-life dimension. A person’s sense of meaning in life and achievement of desired goals is closely related to hope. With hope, individuals are motivated to pursue their expectations and strive to achieve their life goals. Therefore, the method presented in this study is suitable for psychological interventions grounded in social support to enhance the psychological well-being of stunted adolescents.

The final aspect of psychological well-being is personal growth. Personal growth is an individual's ability to continue developing their potential and to improve their positive qualities [17]. To improve self-esteem, individuals need self-awareness and a willingness. Therefore, to become better people, individuals should be aware of self-development [56]. A person who has personal growth views themselves as an individual who is continually developing, open to new experiences, capable of realizing their own potential, able to perceive improvements in themselves through their behavior at any time, and able to become a more effective person with increased knowledge [57]. On the other hand, someone who has poor personal growth may feel they are experiencing stagnation, unable to see improvement or self-development, bored and losing interest in life, and unable to develop better attitudes and behaviors [57]. Fatmawaty states that stunted teenagers often feel inferior, embarrassed, sad, and annoyed, and that they feel different from other people, especially when in a new environment [34]. As a result, they hesitate to enter new environments, which prevents them from trying new things due to fear of receiving negative treatment from others. Consequently, these circumstances hinder their personal growth. Cai and Lian stated that social support from the surrounding environment influences individuals’ personal growth [58]. Social support provided by family, peers, and the environment may increase an individual's positive emotions, helping them feel appreciated and perceive their life as more meaningful.

The psychoeducation used in this study to increase personal growth was a 40-day self-improvement challenge. Participants were given examples of challenges, including learning new skills, joining communities of interest, taking free online courses aligned with their interests, developing their potential skills, and more. The purpose of this challenge was to encourage participants’ continuous motivation to develop their potential by fostering and improving their positive qualities. The challenges were given to promote personal growth closely related to social support.

Based on the explanation above, providing social support-based psychoeducation to short-statured students at SMK PP Padang Mengatas is effective in improving psychological well-being in the short term. However, this study cannot determine the long-term effects on students’ psychological well-being. Therefore, it is recommended that future research include assessments several weeks after the psychoeducation program. In addition, the program should be tested on a larger sample to obtain more comprehensive results.

6. STUDY LIMITATION

This study was conducted with a relatively small and homogenous sample from a single school, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to wider adolescent populations. Moreover, the short follow-up period restricted the ability to capture the long-term effects of the psychoeducation program. These limitations highlight the need for future studies to employ larger, more diverse samples, thereby increasing statistical power and broadening applicability across diverse cultural and social contexts. In addition, incorporating longitudinal follow-up assessments would enable researchers to evaluate whether the positive outcomes observed are sustained over time, thereby addressing the critical question of intervention durability. Beyond quantitative evaluations, the integration of mixed-method approaches, such as qualitative interviews or focus groups, would provide richer insights into participants' lived experiences and perceptions, complementing statistical findings with contextual depth. Together, these methodological improvements would not only validate and refine the psychoeducation intervention but also enhance its practical relevance for both research and implementation in real-world adolescent populations.

CONCLUSION

Adolescents with short stature are facing internal and external pressures that can affect their psychological well-being. Psychological well-being is important for adolescents to help them adapt to changes. One factor that affects psychological well-being is social support from family and peers. Providing social support-based psychoeducation has been proven effective in improving psychological well-being in stunted adolescents, as indicated by a significance value of 0.003 in the paired sample t-test and an increase in the average psychological well-being score of 27.64 in the experimental group. On the other hand, the average psychological well-being score in the control group decreased by 4.92. The provision of psychoeducation involving groups is considered appropriate for improving psychological well-being. In addition, providing social support-based tasks can help train adolescents to improve their psychological well-being in each dimension. Furthermore, this psychoeducation module can be an alternative approach to improve psychological well-being in adolescents.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: R.S.P.: Contributed to the study conception and design; R.S.R.: Responsible for the methodology; T.R.: Conducted the analysis and interpretation of results; M.P.A.: Handled writing, reviewing, and editing; F.A.: Contributed to writing the paper; A.C.P.: Carried out the validation. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| SSGI | = Indonesian Nutrition Status Survey |

| Kemenkes | = Ministry of Health, Republic of Indonesia |

| WHO | = World Health Organization |

| SMK | = Vocational High School |

| SPSS | = Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

| CTL | = Contextualized Teaching and Learning |

| IQ | = Intelligence Quotient |

| mTORC1 | = Mammalian Target of Rapamycin Complex 1 |

| WRAT | = Wide Range Achievement Test |

| REBT | = Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy |

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

This study did not require formal approval from an institutional review board, as it was conducted within a school-based educational program with minimal risk.

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

All human research procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the committee responsible for human experimentation (institutional and national), and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2013.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Participation in this study was voluntary, and written informed consent was obtained from all adolescent participants prior to data collection. Confidentiality and anonymity were strictly maintained throughout the research process.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

The data and supporting information are available in the article.

FUNDING

This work was partially supported by the Institute for Research and Community Service (LPPM), Andalas University, Indonesia.

ACKNOWLDEGEMENTS

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the Education Office of West Sumatra Province, Indonesia, for its support, and to SMK PP Padang Mengatas (Vocational School of PP Padang Mengatas), Limapuluh Kota Regency, for its valuable collaboration in this research.