All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Parental Control over Child Video Game Use: A Systematic Review of Parental Opinions and their Impact on Family Relationships

Abstract

Introduction

Parents face challenges in their children’s education, including the use of video games. While offering benefits, concerns about mental and physical health and academic performance lead some parents to set usage rules, often causing conflicts. This study evaluates parental opinions, the extent of parental control, and its impact on family relationships.

Methods

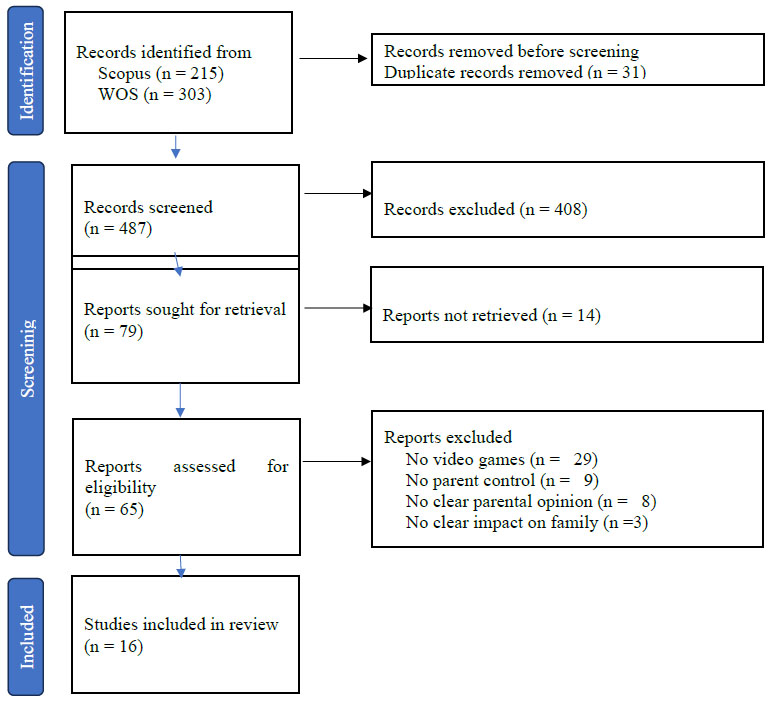

Using a systematic approach, 518 articles from Scopus and WOS databases (2000–April 2025) were screened for data quality, relevance, mediation strategies, parental opinions, and the impact of video games on families. Only 16 articles were analyzed after being selected using the PRISMA 2020 and CASP checklists to minimize bias.

Results

Parental control over children’s video game use mainly involves restrictive strategies like rule-setting and content bans, often due to concerns about addiction and violence, leading to reduced communication and increased parent-child conflict. Less common interactive methods, such as co-playing and active mediation, can enhance family cohesion. Parental perspectives vary; some recognize the social and cognitive benefits, promoting less restrictive and more engaging approaches. The impact of parental control on family dynamics depends on the quality of the relationship.

Discussion

The review highlights that strict parental controls, though common, often create family tension, particularly with teenagers, due to their authoritarian nature. Co-playing fosters better family bonding and communication. Parental perceptions, shaped by both cultural and individual factors, influence the control styles they employ. Positive perspectives encourage involvement. These findings challenge traditional mediation models and support autonomy-promoting approaches.

Conclusion

Parents should avoid overly restrictive control over video games, striking a balance between concerns about children’s vulnerability and interactive methods, such as gatekeeping, discursive mediation, and investigative efforts. Further research on the social, academic, and economic impacts of video games, children’s developmental stages, and their potential to strengthen family bonds will guide parents and families.

1. INTRODUCTION

Video games have become a ubiquitous aspect of contemporary childhood, profoundly influencing the entertainment and social lives of millions of young people globally [1]. While acknowledging the undeniable benefits of this leisure activity, such as its positive impact on cognitive, motivational, emotional, and social development [2], a balanced perspective is crucial, as parental concerns regarding potential adverse effects are inevitable. Adolescent gaming can present problematic aspects, including risks of exposure to violent or inappropriate content, excessive screen time, and addiction [3, 4]. It also contributes to physical health risks and sedentary lifestyles [5, 6] and can occasionally affect parents and family life, potentially leading to parental depression and anxiety [7]. Consequently, parental mediation is a vital practice for safeguarding teenagers, particularly concerning their online privacy, as parents serve as crucial role models in their children’s development [8, 9]. Parents employ a range of mediation strategies to regulate their children’s gaming, encompassing restrictive measures (e.g., limiting playtime or content), active engagement (e.g., discussing game narratives), and co-playing (e.g., participating alongside their children) [10, 11]. These efforts aim to protect children from harm, yet their broader implications extend to family dynamics, influencing communication patterns, trust, and emotional bonds within the household [12, 13]. As digital technologies become increasingly integrated into daily life, understanding the intersection of parental control and video game use is essential for fostering healthy family environments [14]. The stakes are significant; poorly managed gaming can exacerbate tensions and may be associated with poor social skills [15], whereas effective strategies can strengthen familial ties [16].

The landscape of parental mediation is multifaceted, reflecting diverse approaches that vary in their emphasis on restriction, engagement, or collaboration. Restrictive mediation, characterized by setting rules or limits on gaming time and content, is the most commonly reported strategy across studies [17, 18]. This approach often stems from parental apprehensions about the potential harms of gaming, such as addiction or exposure to violent content, as highlighted in studies from Turkey [19] and Peru [20]. However, this review also identifies a growing recognition of more interactive forms of mediation, such as active mediation, where parents engage in discussions about game content, and co-playing, which involves parents participating in gaming alongside their children. For instance, Singaporean parents utilize discursive strategies, involving discussions about video gaming content and potential risks, and investigative strategies, which entail information-seeking and skill acquisition activities to effectively mediate their children’s video gaming activities [21]. Similarly, Norwegian parents leverage co-playing to strengthen family bonds [22]. These participatory methods, though less prevalent, are associated with more positive relational outcomes, suggesting that the manner in which control is exercised significantly influences family dynamics.

Parental attitudes toward video games are frequently divided, influencing the types and extent of their mediation strategies. Many parents express concerns about negative outcomes, such as aggression, health risks, or social isolation, which drive them toward restrictive controls, as evidenced by Swedish parents of adolescents with gaming disorders reporting heightened worries about gaming’s impact [23], and rural Chinese parents citing fears of academic decline and weakened family ties [24]. Conversely, video games can enhance teenagers’ quick thinking and skill development [25], leading a subset of parents to acknowledge the potential benefits of gaming, such as cognitive development or opportunities for social connection [26, 27]. Such recognition leads them to adopt more permissive or collaborative approaches. A study reported that Dutch parents who perceive cognitive advantages in games are more likely to engage in co-playing [18], while another highlights how gamer-parents in Norway view gaming as a valuable social activity [22]. This divergence in perception underscores the subjective nature of parental attitudes, influenced by factors, such as personal gaming experience, cultural norms, and the specific characteristics of the child, including age and gender [17, 28].

The impact of parental control on family relationships is complex and contingent on both the type of mediation employed and the relational context. Restrictive strategies, while sometimes effective in curtailing problematic gaming behaviors, are frequently linked to adverse relational outcomes, such as increased parent-child conflict, reduced communication, and heightened secrecy or defiance, particularly among adolescents. Restrictive control is associated with lower openness and greater secrecy in Swedish teens with gaming disorders [23], while Peruvian families experience strained relationships due to gaming-related disputes [20]. In contrast, active mediation and co-playing often correlate with improved family cohesion, fostering open dialogue and mutual understanding. Active-emotional co-use among German families is associated with a positive family climate [29], while in Norwegian households, gaming is regarded as a practice that fosters unity [22]. However, the effectiveness of these strategies is not uniform; it varies based on factors, such as the child’s age, gender, and the overall family environment, with restrictive control potentially more beneficial for younger children [30] but provoking resistance in older ones [28]. Aggressive restriction can be harmful and may lead to child-to-parent violence; some studies correlate child-parent violence with early child abuse by parents [31-33].

Central to these dynamics is the quality of the parent-child relationship, which emerges as a crucial mediator in the effectiveness of control strategies. Studies [34, 35] demonstrated that strong parental bonds and clear communication about gaming expectations are more effective in protecting against gaming disorder and in reducing excessive or violent gaming than rigid rule enforcement alone. However, restrictive parental control strategies dominate video game mediation [36], yet their effectiveness is mediated by parent-child relationship quality. Authoritarian approaches correlate with family conflict and problematic gaming behaviors [21]. This raises a critical question: How can parental control reconcile child protection with family harmony when digital interactions increasingly define childhood [37]? Focusing on families with children/adolescents (0-18 years) engaged in video gaming, we examine parental control of children’s video game use, comparing strategies and approaches adopted by parents. Moreover, it also assesses their impact on family relationships, communication, and well-being. Our aim is to evaluate how parental control affects family relationships, with the goal of identifying effective practices and strategies for families. This will provide valuable insights into this important sociological issue [36].

2. METHODS

This systematic review was conducted following the PRISMA 2020 Fig. (1) process of selection to ensure a systematic, transparent, and replicable approach to the literature synthesis. Initial searches across Scopus (n=215) and WOS (n=303) yielded 518 records. After removing 31 duplicates, 487 unique records proceeded to the screening phase. This stage involved an independent review of titles, resulting in a total of 408 records being excluded. Subsequently, 79 reports were sought for full-text retrieval, with 14 not retrieved. The remaining 65 reports were assessed for eligibility, with a focus on the interplay between video games, parental opinions, parental control, and family relationships. This stringent process, guided by the PRISMA flowchart, ultimately included 16 studies for synthesis, with discrepancies resolved via consensus based on predefined inclusion criteria.

PRISMA flowchart of the selection process for articles included in the review.

2.1. Information Sources

The literature search was conducted using two highly regarded academic databases, Scopus and Web of Science (WOS). These databases were selected for their comprehensive coverage of peer-reviewed journals in the social sciences, particularly sociology and psychology, and for their reputation for indexing high-quality and impactful research. Scopus offers a broad interdisciplinary scope, while Web of Science ensures selectivity by including only journals meeting stringent quality criteria. Together, they provided a robust foundation for capturing relevant studies.

2.2. Search Strategy

A carefully designed search strategy was employed to identify studies addressing video games, parental control, and family relationships. The search utilized a combination of keywords and their synonyms, connected through Boolean operators, to maximize the retrieval of relevant articles. The following search string was applied consistently across both databases: “Video games” OR “esports” OR “electronic games” OR “gaming” AND “parents” OR “family” AND “mediation” OR “parental control” OR “control” OR “supervision” OR “family problems” OR “family conflicts”. To enhance precision, the search was refined by restricting the publication period to 2000–2025 to capture contemporary developments in video gaming and family dynamics, limiting the languages to English and French to ensure accessibility and relevance to the research team, and restricting the disciplines to sociology and psychology to align with the review’s theoretical framework. These parameters ensured that the retrieved studies were both current and directly pertinent to the sociological and psychological aspects of the research question.

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

To ensure the inclusion of relevant and high-quality studies, only peer-reviewed articles published in academic journals were included, ensuring rigorous evaluation by experts, while conference papers, book chapters, theses, and non-peer-reviewed sources were excluded. Studies published between 2000 and April 2025 were considered to capture contemporary developments in the field of video games and family dynamics while remaining relevant in current technological and social contexts. Additionally, articles written in English or French were included to ensure accessibility and comprehension by the research team. Furthermore, studies had to have a direct link to sociology or psychology, as these disciplines provide the theoretical framework for analyzing family relationships and parental control in the context of video games. Participants in the studies had to include children aged 0 to 18 years and their parents or families, so that the results were directly applicable to the review’s objective on parental control and family dynamics. Moreover, studies had to examine video games, including esports, electronic games, or gaming in general, and parental control measures, such as mediation, supervision, or restrictions, with studies not explicitly addressing these two elements being excluded. Included studies also had to report data on parents’ control strategies and opinions regarding video games and the impact of video games and parental control on family relationships, such as family cohesion, conflicts, or communication, while research focusing solely on gaming behaviors without reference to family dynamics or parental perspectives was excluded. Finally, no geographical restrictions were applied, allowing for a global perspective on the subject. These criteria ensured that the selected studies were both methodologically sound and directly relevant to the sociological and psychological dimensions of video games, parental control, and family relationships.

2.4. Data Extraction

Data were extracted from the selected studies using a standardized form to ensure consistency and completeness of the information. For each study, information included the study design (e.g., qualitative, quantitative, or mixed methods), sample characteristics (e.g., age range of children, family demographics, geographic context), variables of interest (e.g., forms of parental control, children’s gaming habits, family relationship outcomes), and key findings (e.g., parental opinions on video game mediation, observed impacts on family cohesion or conflict). The extraction process was conducted independently by reviewers for a subset of studies to verify inter-rater reliability, with any discrepancies resolved through discussions based on predefined criteria. This collaborative approach minimized bias and ensured data accuracy for synthesis.

2.5. Assessment of Study Methodology

The methodological quality of the included studies was rigorously evaluated to ensure the reliability and validity of the review’s findings. Each study was assessed based on the suitability of its study design for exploring the research question, such as whether it employed cross-sectional or longitudinal approaches, sample size and representativeness, particularly in reflecting diverse family and gaming contexts, the appropriateness of data collection methods for measuring key constructs, and the soundness of its analytical techniques, whether statistical or thematic.

Quantitative studies were evaluated using an adapted version of the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool, focusing on potential biases, such as selection, performance, and reporting biases [38]. Qualitative studies were appraised using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklist [39], which emphasizes the clarity of objectives, methodological coherence, and trustworthiness of findings (CASP Checklists - Critical Appraisal Skills Programme, 025). For mixed-methods studies, a combined approach was applied. This thorough evaluation ensured that only studies of high methodological quality contributed to the final analysis.

3. RESULTS

The systematic review encompassed a diverse range of studies; this section details 2 frameworks. The first one is dedicated to characteristics, and the second one to the synthesis of the 16 studies that the systematic review included after meeting the stringent eligibility criteria and reflecting a diverse array of methodologies.

As detailed in Tables 1 and 2, studies varied significantly in their geographical origin, participant demographics, methodological approaches, and the variables investigated. Studies originated from countries, such as the USA, China, Turkey, Peru, Spain, Canada, Singapore, Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, and Norway, reflecting a broad international perspective on parental control of video game use.

| Reference Number |

Title | Country | Participants | Methodology | Variables measured |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [35] | Parental Influence on Youth Violent Video Game Use | USA | High school students (n=3,115) and middle school students (n=2,989) from the Delaware Youth Risk Behavior Survey | Quantitative (cross-sectional survey analyzed with ordinal regression models) | Frequency of violent video game play Perceived parental opinion of violent video games |

| [24] | Chinese Rural Children's Video Game Disorder: Processes, Harms, and Causes | China | 21 sixth-grade students (15 boys, 6 girls), 7 parents, 7 teachers from 5 rural primary schools in Zhejiang Province | Qualitative (in-depth interviews, grounded theory with three-level coding) | Impact of playing video games Causes of video game disorder Interventions in video game disorder Parents’/teachers’ attitudes toward playing video games |

| [19] | Digital Games Pre-Schoolers Play: Parental Mediation and Examination of Educational Content | Turkey | 109 parents of 60–72-month-old children attending preschool in Kars, Turkey | Mixed-methods (convergent parallel design using surveys, interviews, document analysis) | Parental mediation strategies Content of games Parents’ knowledge and perceptions of games |

| [20] | Digital Gaming and the Arts of Parental Control in Southern Peru: Phatic Functionality and Networks of Socialization in Processes of Language Socialization | Peru | Parents of boys aged 13-19 who are avid gamers, from the Department of Puno, Peru | Qualitative (unstructured interviews with parents, observations of family interactions) | Parental control strategies Parents' perceptions of gaming Impact of gaming on family relationships |

| [28] | Gender Dynamics in Video Game Use: Usage Patterns, Parental Control Motivations, and Effects in Spanish Adolescents | Spain | 2,567 secondary school students (mean age 14.89, SD=1.90), 51% male, 48.1% female, 0.9% non-binary (excluded from analysis) | Quantitative (cross-sectional, descriptive observational study) | Video game use patterns (time, money, game mode, device, type), Parental control perceptions Problematic use Motivations, Passion levels (harmonious/obsessive) PEGI adherence |

| [41] | I Think He Is in His Room Playing a Video Game: Parental Supervision of Young Elementary-School Children at Home | Canada | 74 mother-child dyads (children aged 7-10 years, M = 8.49, SD = 1.52, 36 boys, 38 girls) | Mixed-methods (surveys, diaries) | Supervision patterns: direct, indirect, none, Child injury history (lifetime, 3 months prior, during study), Child risk-taking propensity (RPS), Parental permissiveness (PAQ-R), Child activities Home location. |

| [21] | Level Up! Refreshing Parental Mediation Theory for Our Digital Media Landscape | Singapore | 41 parent-child dyads (children aged 12-17 playing FPS or MMORPG) | Qualitative (interviews) | Parental mediation activities (gatekeeping, discursive, investigative, diversionary) |

| [43] | Playing by the Rules: Parental Mediation of Video Game Play | USA | 433 parents of children aged 5-18 years | Quantitative (survey) | Parental mediation (restrictive, active, coplaying) Parental involvement Child delinquency |

| [29] | Parental Mediation of Children’s Television and Video Game Use in Germany: Active and Embedded in Family Processes | Germany | 158 parent-child dyads (children aged 9-12, mean age 11.07, parents aged 30-55, mean age 42.66, 80% mothers, balanced child gender) | Quantitative (survey-based, questionnaires for parents and children, factor and regression analyses) | Parental mediation strategies (active-emotional co-use, restrictive, patronizing) for TV and video games Family climate (satisfaction, conflicts), Parental beliefs about media effects (positive, negative) |

| [10] | Parental Mediation of Teenagers' Video Game Playing: Antecedents and Consequences | United States | 1102 parent-adolescent dyads (adolescents aged 12-17, parents/guardians) | Quantitative (telephone survey) | Parental mediation (co-playing, game rating checking, stopping game playing) Presumed influence of video games (positive, negative, neutral) Teen gaming behaviors (frequency, prosocial, deceptive) Demographics (age, gender, income, education) |

| [18] | Parental Mediation of Children’s Videogame Playing: A Comparison of the Reports by Parents and Children | Netherlands | 536 parent-child dyads (parents: 51% fathers, mean age 41.7, children: 59% boys, mean age 12.4, aged 8-18) | Quantitative (online survey) | Parental mediation strategies (restrictive, active, co-playing) Parental perceptions of game effects (positive or negative on cognitive, social-emotional, learning, behavioral, and health) Demographics (parent/child age, gender, education, family size) |

| [42] | Parents' Interest in Videogame Ratings and Content Descriptors in Relation to Game Mediation | Netherlands | 765 Dutch parents (52% mothers, mean age 40.07, SD = 6.55) with children aged 4-18 (56% boys, mean age 10.67, SD = 4.18) | Quantitative (cross-sectional survey with LISREL modeling) | Interest in ratings (age, harmfulness) Interest in content descriptors (realistic gore, alcohol/drugs, fantasy violence, bad language, nudity) Gaming behavior (parent, child) Perceived game effects (positive, negative) Parental mediation (restrictive, active, social co-play) Demographics (parent/child age, gender, education) |

| [30] | Parents' Degree and Style of Restrictive Mediation of Young Children's Digital Gaming: Associations with Parental Attitudes and Perceived Child Adjustment | Belgium | 762 parents (82.6% mothers, mean age 35.27, SD = 5.65) of children aged 3-9 (mean age 5.52, SD = 1.86, 55.8% girls) | Quantitative (cross-sectional survey with SEM) | Degree of restrictive mediation Style of mediation Parental attitudes toward gaming Perceived child outcomes as defiance Problematic gaming Interest in social play Demographics (child/parent gender, age, education). |

| [40] | The Effectiveness of a Parental Guide for Prevention of Problematic Video Gaming in Children: A Public Health Randomized Controlled Intervention Study | Norway | 1657 guardians of children aged 8–12 years from 6000 (initial sample), 831 received the guide and were included after returning the questionnaire, and 826 received no intervention and were included after returning the questionnaire. | Quantitative (randomized controlled trial with a 4-month follow-up survey) | Problematic video gaming (IGD criteria) Sleep problems and bedtime resistance Parental mediation (restrictive, co-playing, active) Parental limit-setting efficacy Time spent gaming Guardian satisfaction with the guide |

| [22] | The Involved and Responsible Outsiders: Norwegian Gamer-Parents Expanding and Reinforcing Contemporary Norms of Parenthood | Norway | 29 gamer-parents (18 men, 11 women), aged 32–48, with children aged 0–17 | Qualitative (28 semi-structured interviews, face-to-face or via Skype, 30 min–2 hr, transcribed and anonymized) | Positioning of gamer-parents versus non-gamer parents Information and advice source Type of expertise in decision-making Perceptions of gaming risks/benefits Parenting norms (involvement, responsibility, balance) Mediation strategies |

| [17] | Video Games, Parental Mediation, and Gender Socialization | Spain | Quantitative: 186 parents (20.4% fathers, 79.6% mothers) of children aged 8–9 (3rd grade) and 12–13 (6th grade), 92 boys, 94 girls Qualitative: 44 parents (37 mothers, 7 fathers) in 4 discussion groups |

Mixed, quantitative by questionnaires, and qualitative by discussion groups | Use of video games (time, context, type) Parental mediation styles (instructive, co-playing, restrictive) Parental beliefs (positive/negative) Perceived difficulties Child’s sex and age |

Participants varied widely, including high school and middle school students, sixth-grade students, parents of preschoolers, parents of avid gamers, secondary school students, mother-child dyads, and parent-child dyads across different age ranges (from 3-9 years to 12-17 years).

Methodologies employed included quantitative cross-sectional surveys, qualitative in-depth interviews, grounded theory, mixed-methods designs (convergent parallel, surveys with diaries), and randomized controlled trials.

The variables measured were extensive, covering aspects, such as frequency of violent video game play, perceived parental opinion, causes and interventions for video game disorder, parental mediation strategies (restrictive, active, co-playing, gatekeeping, discursive, investigative, diversionary), content of games, parents' knowledge and perceptions, impact of gaming on family relationships, video game use patterns (time, money, game mode, device, type), problematic use, motivations, passion levels, PEGI adherence, supervision patterns, child injury history, risk-taking propensity, parental permissiveness, child activities, parental involvement, child delinquency, family climate, parental beliefs about media effects, presumed influence of video games, teen gaming behaviors, demographics (age, gender, income, education), parental perceptions of game effects (cognitive, social-emotional, learning, behavioral, health), interest in ratings and content descriptors, parental attitudes toward gaming, perceived child outcomes (defiance, problematic gaming, interest in social play), problematic video gaming (IGD criteria), sleep problems, bedtime resistance, parental limit-setting efficacy, time spent gaming, guardian satisfaction, positioning of gamer-parents versus non-gamer parents, information and advice sources, type of expertise in decision making, perceptions of gaming risks/benefits, parenting norms, and child's sex and age. This comprehensive scope allowed for a nuanced understanding of the complex interplay between parental control, video game use, and family dynamics.

This study reveals a nuanced landscape of parental control over children's video game use, deeply intertwined with parental perceptions and significant impacts on family dynamics. We observed a spectrum of control types, ranging from restrictive measures, such as setting time limits and content prohibitions, to more active and involved approaches, including co-playing and discursive mediation. Interestingly, restrictive mediation, while prevalent, often led to conflict and could even have unintended negative consequences, such as increased problematic gaming [40].

Parental opinions on video games are far from monolithic. While many parents express concerns about violent content, addiction, and academic neglect, a notable segment also acknowledges the potential educational and social benefits of gaming [18, 20]. This duality in perception directly influences the chosen mediation strategies. For instance, parents with negative views tend to employ more restrictive controls, whereas those who see positive aspects are more inclined towards active or co-playing strategies [19].

The impact on family life is a critical dimension. Excessive gaming and overly restrictive control often strain parent-child relationships, leading to increased conflict and communication breakdown [21, 41]. However, studies also highlighted the potential for positive family interactions. Co-playing, in particular, emerged as a powerful tool for fostering stronger bonds and enhancing rapport [22, 42]. A fascinating counter-narrative from Norway [40] showcased how gamer parents successfully integrated gaming into family life, viewing it as a constructive bonding activity that challenges the prevailing apprehensions often associated with video games.

| Reference Number | Type of parental control | Parent opinion | Impact on Family life | Key results | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [35] | Parental bond: A focus on attachment/relationship quality, Parental discipline, Rule enforcement. |

Measured via youth perception, when 68.5% of high school males and 45.5% high school females reported that their parents see it as “not wrong at all”. Middle school students reported slightly higher disapproval. |

Stronger parental bonds linked to less violent game play, Stronger disapproval linked to less play, Influencing gaming can foster stronger bonds and reduce tension. |

Stronger perceived parental disapproval reduces violent game play, Stronger parental bonds reduce play, Military parent increases the likelihood of playing violent video games, Effects are stronger in middle school than in high school. |

Parental opinions and bonds significantly shape youth violent video game play, with influence decreasing as children age, Parents can leverage strong bonds and clear opinions to guide gaming habits, Further research is needed on attachment, other influences, and direct parental opinions. |

| [24] | Inactive (material satisfaction without supervision), Low engagement, Restrictive (violent communication to halt gaming). |

Concerned about gaming but lack effective strategies, some use restrictions, others are permissive due to work or ignorance. | Negative: reduced parent-child interaction, Increased conflict (e.g., violence from children), Weakened family bonds, Communication breakdown. |

Gaming disorder follows four processes: entering, immersing, exiting, and re-entering, Harms include cognitive decline, health issues, poor academics, and strained relationships, Causes include equipment access, poor infrastructure, and guidance. |

Joint efforts from families, schools, communities, and society are needed, Balanced parenting, School prevention programs, community support, and gaming regulation are recommended. |

| [19] | Co-playing, Viewing, Restrictive, Active, Laissez-Faire. |

Parents express concern about violent content and online risks; some use mediation consciously, others, i.e., 49.5% believe games can be educational; others view games as harmful (e.g., causing aggression, addiction). |

Negative because it reduced parent-child interaction (children withdraw during gaming), and favours conflicts due to aggressive child behaviour when restricting access. It also increases parental stress over monitoring. Positive (educational games seen as supportive). |

Only 9% of parents use conscious mediation (e.g., co-playing, active), 74% of VG played are violent, 18% educational, 8% neutral, 78.8% of parents knew the objective of the digital game their children play, 50.4% of the parents thought that VG played by their children was safe, 86.2% of the parents stated that they observed their children playing VG, 45.0% of the parents played digital games with their children, 27.5% of the parents stated that their children behaved aggressively during VG, 49.5% of the parents thought that VG contributed to their children’s education. |

Parental education level influences mediation, need for expert guidance, and better educational game design, suggesting parental training on mediation strategies, Develop high-quality educational games with expert input, Collaborate with schools/governments to regulate game content and promote digital literacy. |

| [20] | Monitoring and disciplining face-to-face, Delegate monitoring in the absence of family members. |

Parents view control as necessary to prevent moral decline (e.g., neglect of schoolwork, deception), and control is seen as a way to maintain family and cultural values and obligations. | Negative (conflicts arise from excessive gaming and control efforts, strained parent-child relationships due to gaming's allure and peer influence). | Parents use strategies like physical monitoring, restricting access, and peer networks compete with parental authority, making control challenging. | Parental control must consider social and cultural contexts, Strategies should address peer influence and the social nature of gaming, Secommend a balanced approach that integrates control with an understanding of gaming's role in socialization. |

| [28] | Restrictive (time/money/game type control), Monitoring by PEGI recommendation, Ender-differentiated supervision. |

Adolescent-reported: Girls perceive higher parental control than boys, nearly half ignore PEGI recommendations. | Negative: Potential conflicts due to excessive use and lack of PEGI adherence, and gender differences in supervision. | Boys spend more time/money on games, with higher problematic use (64.4% versus 20.3% girls), Girls reported more parental control; 50% of adolescents ignored PEGI, especially girls. |

Address gender-specific needs in interventions, Enhance parental involvement to mitigate problematic use, Encourage collaborative play, Promote research into the impact of video games on different genders, Promote awareness of PEGI and healthy gaming habits. |

| [41] | Direct (constant watching), Indirect (intermittent checking), Inactive (no supervision). | Inferred via behavior (e.g., permissive mothers tend to supervise less; higher child risk-aversion ratings correlate with increased supervision), Parents view direct supervision as critical for safety. |

Negative: More indirect/no supervision linked to higher injury risk, Potential for conflict if unsupervised gaming leads to injuries. |

Children were alone 24% of the time mostly indirectly supervised, (41.67%) or unsupervised (54.17%). Children who were high in risk-taking correlated with no supervision, Time left unsupervised was influenced both by child attributes (i.e., risk-taking propensity) and parenting style (i.e., permissiveness), Direct supervision correlated with fewer injuries, Unsupervised time increased conflict over safety. |

Direct supervision is compensatory, reducing injury risk, Indirect/no supervision is a risk factor, Consider parenting style and child traits in supervision strategies. |

| [21] | Gatekeeping (regulating exposure), Discursive (discussions), Investigative (information-seeking), diversionary (encouraging alternatives). |

Parents view mediation as essential to balance gaming risks and benefits, Adapting strategies to child behavior and game evolution. |

Discursive activities may enhance parent-child dialogue, suggesting potential positive relational effects. Engagement via discursive activities improves rapport, Gatekeeping causes conflict. |

Parents employ a dynamic mix of gatekeeping, discursive, investigative, and diversionary activities, refining traditional restrictive, active, and co-use mediation. | Recommends updating parental mediation theory with four activities (gatekeeping, investigative, discursive, and diversionary) to reflect modern media complexities, suggests broader applicability, and further research across contexts. |

| [43] | Restrictive (rules on content, genre, ratings), Active (negative, neutral discussions), Co-playing (playing together). |

Parents view mediation as necessary to manage gaming’s risks and benefits. | Co-playing and neutral mediation may foster positive interactions, while negative mediation could lead to conflict, especially with older children. | Parents use restrictive, negative, neutral mediation, and co-playing, Parental involvement predicts mediation, except for negative mediation; restrictive and negative mediation relate to child delinquency. | Recommends further research on the valence of mediation and its effects on family dynamics, and suggests age- appropriate mediation strategies to avoid conflict. |

| [29] | Active-emotional co-use (AEC) by emotional discussions (e.g., empathy) and joint media use, Restrictive mediation as rules, restrictions, critical discussions (e.g., media versus reality), Patronizing mediation by monitoring, Shared use upon the child's request. |

Influenced by fear of negative effects (predicts AEC and restrictive) and belief in positive effects (predicts patronizing for VGs). | Positive family climate linked to more AEC, less restrictive mediation, High media use linked to family difficulties. |

Restrictive mediation is the most common for TV and VGs, AEC and patronizing more frequently for TV than VGs, Fear of negative effects drives AEC and restrictive mediation. Positive family climate boosts AEC, and it correlates with less media/video games use, Parent–child agreement on mediation reduces conflict. |

Active communication is key across all strategies, The role of cognitive beliefs about media effects in increasing children’s acceptance of rules and in preventing exposure to inappropriate video games, Promote media literacy for realistic parental views, Encourage AEC to enhance family connectedness. |

| [10] | Game rating checking, Stopping game playing, Co-playing. |

Parents with negative perceptions restrict more, Positive perceptions encourage co-playing. | Restrictive mediation may lead to conflict (boomerang effect). | Parental mediation decreases with teenagers, Negative influence perception linked to restrictive mediation, Game rating checking positively correlates with game frequency and deceptive behaviors. |

Restrictive mediation may have unintended negative effects (e.g., increased gaming), Recommend interactive, dialogue- based mediation over strict restrictions. |

| [18] | Restrictive by time and content control (e.g., monitoring, forbidding games), Active by discussing the pros/cons of games, Co-playing by joining a game with a child. |

Believe in both positive effects and negative effects, Mediation linked to these beliefs (e.g., restrictive/active for negative, and co-playing for positive). |

Restrictive/active mediation may reduce negative effects, but risks conflict, Co-playing fosters positive interaction. |

Three mediation types were identified: restrictive (most common), active, and co-playing (least common), Restrictive/active mediation was higher with negative effect concerns, and co-playing with positive social- emotional views, More mediation for younger children and girls. |

Mediation mirrors VG patterns but with a unique frequency (restrictive dominant), Tailor strategies to the child's age and perceived effects, Future research must study the relationship between children playing (inappropriate) games and the specific parental mediation strategies. |

| [42] | Restrictive by rules/prohibitions on game content, Active by critical discussion of games, Social co-play by playing with a child. |

Majority find ratings and content descriptors necessary, realistic gore most critical, nudity least, varies by demographics (e.g., younger child’s parents are more interested). | Restrictive/active mediation linked to negative effect concerns, potentially reducing conflict, and social co- play linked to positive effects, enhancing bonding. | 77% want age ratings, and 78% harmfulness ratings, Realistic gore is the top concern, and nudity is the least, Restrictive/active mediation is strongly tied to ratings interest and negative effect views, Co-playing correlates with parents’ own gaming and positive views of games. |

Ratings and content descriptors are key tools for restrictive/active mediation, whereas co-play is less associated with these factors, which are strongly tied to parents’ own gaming habits and views on the positive effects of games, PEGI should refine descriptors (e.g., separate realistic versus fantasy violence), Future research needs longitudinal data to establish causality between interest in a rating, perception of VG effects, and the application of parental mediation. |

| [30] | Restrictive by the degree of rules/restrictions, Autonomy-supportive by empathetic and explanatory style, Controlling in a punitive and coercive style. | Negative views linked to controlling style, suggesting concern over gaming’s harm. | Higher restrictive degree linked to less conflict (less defiance), Controlling style linked to more conflict (more defiance, problematic use), and autonomy- supportive neutral. | Negative attitudes predict parent controlling style, not degree or autonomy- supportive style, Higher restrictive degree linked to less defiance, less problematic use, and more interest in social play, Controlling style correlated with more defiance and problematic use perception. |

Clear rules are beneficial, but controlling style is counterproductive, promoting nuanced attitudes to reduce control, Longitudinal research is needed for causality and to explore cultural contexts and other mediation types (e.g., co-use). |

| [40] | Restrictive mediation by rules and limits on gaming time and content, Co-playing by playing games with the child, Active mediation by discussing game content and explaining fantasy versus reality. |

The guide with advice and strategies for regulating had a positive impact on their child. | Positive potential, guardians who followed the guide used more mediation strategies, possibly reducing gaming-related conflicts. | Guardians who read and followed the guide reported more video game problems and used more mediation strategies, 4.8% of children met IGD criteria, with most guardians of these children in the “read and followed” subgroup, compared to the two other subgroups, “read, not followed” and “did not read, did not follow.”, 32.6% (n = 197) of the guardians who received the guide agreed that the guidelines had a positive impact on their child. |

The parental guide did not prevent problematic gaming but was positively received by guardians, May be more effective for families already experiencing gaming issues rather than primary prevention, and beneficial for those in specific need of help regarding this issue. |

| [22] | Parental norms are flexible and can be assembled in many configurations, Participating in the game, Co-playing with children, Time control by being flexible. |

Gamer parents think gaming is a valuable, social, and enriching activity, Non-gaming parents lack knowledge and involvement, Gaming is necessary and a highly effective way of enacting good parenting and having positive bonding in families, but it is unfairly judged, Balance is key to responsible parenting. |

Positive: Most interviewees had multiple examples of how gaming gave a sense of community and belonging, and was an enrichment of their lives. Gaming can strengthen family cohesion by fostering closeness and future nostalgia. | Gamer-parents position themselves as involved and knowledgeable, contrasting with uninvolved non-gamer parents, Gaming is an enriching and meaningful hobby, and, within their families, games are constructed as a type of bonding tool, Non-gaming parents are considered to lack interest and knowledge about their children’s lives, Gaming is justified as a bonding tool but balanced with other activities, such as sports, to align with hegemonic norms, Assemblage theory reveals gaming’s meaning as relational, not inherently good or bad. |

Good parenting entails assembling good parenthood through involved, responsible, risk-managing, reflexive, and knowledgeable use of parental norms, Gaming can enhance family relationships when integrated thoughtfully, with the right games, activities, and social interactions, The flexibility of parental norms and how they are continually changing. |

| [17] | Restrictive, which is the most common (e.g., time control, content restriction), Instructive, e.g., advice, explaining functionality, Co-playing is the least used, And mixed with 21% combined styles. |

Negative beliefs with concerns about excessive time, violent content, physical/psychological risks, social isolation, positive beliefs that value learning, socialization, and cognitive skills. | Negative because excessive play linked to perceived risks (e.g., isolation, health issues), and potential parent- child conflict over time/content, Positive, even if co- playing is rare, but could enhance bonding; instructive mediation may foster understanding, Gendered conflict is potential because of more restrictions/co- playing with boys, suggesting tension over usage. |

Boys play more and online (21.7% versus, 10.6% girls). Restrictive style is dominant and exactly controls playing time, is more instructive by fathers, and co-playing is rare, Parents of 6th-grade boys restrict and co-play more than with girls, Parents tend to impose time restrictions more on sons than on daughters, Children's favourite types of video game, in order from most to least popular are: adventure (17.25%), sport (15.75%), and action/war (5.25%), Difficulties that parents face in relation to mediation are early access, social pressure, and the digital divide. |

Restrictive mediation prevails, reflecting control-oriented concerns, while co-playing is underutilized despite potential benefits, Gendered mediation (more control over boys) reflects socialization norms, Parents should improve and strengthen communication and trust between themselves and their children, Future research should expand the sample to generalize the data or to contrast with other contexts. |

Key results consistently pointed to the complexity of effective mediation. Gender differences were apparent, with some studies indicating higher perceived control over girls than boys [17]. The importance of clear communication and shared understanding between parents and children was a recurring theme, often reducing conflict and increasing compliance [29].

Ultimately, the findings underscore that a one-size-fits-all approach to parental control is ineffective. Recommendations frequently emphasize the need for tailored, age-appropriate strategies, promoting media literacy and encouraging dialogue-based mediation over strict prohibitions. Future research should delve deeper into the long-term effects of different mediation styles and explore cultural nuances to provide more comprehensive guidance for families navigating the digital gaming landscape.

4. DISCUSSION

The study reveals that parental control over children’s video game use is prevalent across diverse cultural and methodological contexts. For example, disapproving of violent games is a form of control [35], while time limits and content bans are key criteria for measuring Internet Gaming Disorder (IGD) in rural Chinese families [24]. Across numerous studies, parents commonly use strategies like rule-setting, monitoring, or prohibitions to regulate gaming behaviour. These restrictive approaches are often driven by concerns about potential risks, including addiction, exposure to violent content, academic decline, or social isolation. Nevertheless, this review also uncovers a variety of alternative strategies, such as active mediation, engaging children in discussions about game content, and co-playing, where parents join their children in gaming. Other strategies, such as discursive and investigative mediation by Singaporean parents, were identified [21], while Norwegian parents were found to play with their children to bolster family ties [22]. Though less common, these interactive methods are linked to more positive relational outcomes, indicating that the type of control exerted significantly shapes family dynamics.

Parental attitudes toward video games play a pivotal role in determining the nature and extent of control strategies. The studies collectively reveal a spectrum of perspectives; many parents voice concerns about negative effects, such as aggression or health risks, prompting them to favour restrictive measures. A study captured Turkish parents’ apprehensions about violent content [19], while a Peruvian one details parents’ fears of moral decline [20]. Conversely, some parents acknowledge potential benefits, including cognitive development, social connectivity, or family bonding opportunities, and thus adopt more permissive or participatory approaches. Dutch parents value the cognitive benefits of games [18], and Norwegian gamer-parents maintain a positive view of gaming as a social activity [22]. This variability underscores the subjective lens through which video games are perceived, shaped by factors like personal gaming experience, cultural norms, and child-specific traits (e.g., age, gender). For example, parents who see gaming as a threat tend to enforce stricter controls, whereas those who view it as a relational tool encourage shared play or dialogue, revealing a direct connection between perception and practice.

The impact of these control strategies on family life emerges as complex, affecting relational dimensions. Restrictive measures, while effective in certain contexts for curbing problematic gaming behaviours, are often associated with negative relational consequences, such as heightened parent-child conflict, diminished communication, and increased defiance in children or secrecy and openness, especially among adolescents with gaming disorders [24, 40]. Furthermore, relationships in Peruvian families are strained due to gaming-related disputes [20]. This effect is especially pronounced when restrictions are perceived as overly authoritarian or misaligned with children’s developmental needs, such as the pursuit of autonomy during adolescence. In contrast, active mediation and co-playing are frequently linked to improved family cohesion, promoting open dialogue and mutual understanding. Moreover, AEC (active-emotional co-use) in families correlates with a positive family climate and presents gaming as a unifying practice [29]. However, outcomes are not uniformly positive; the efficacy of these strategies depends on contextual factors, such as the child’s age and gender, as well as the broader family environment.

For instance, restrictive control may mitigate risks in younger children [30] but spark tensions with older ones [28], while gendered patterns, such as stricter oversight of boys [17], may reflect socialization norms that either ease or intensify relational strain. Key findings from the studies provide detailed insights into these dynamics. Overall, the quality of parent-child relationships emerges as a critical mediator; strong bonds and clear disapproval of harmful gaming behaviours consistently reduce excessive or violent play, suggesting that relational factors may outweigh the effects of stringent rule enforcement [35]. Additionally, the distinction between the degree of restriction (how much control is applied) and its style (how it is conveyed) reveals significant nuances. Autonomy-supportive styles, characterized by empathy and explanation, tend to foster better child adjustment and fewer conflicts [30], whereas punitive or coercive approaches are linked to defiance and problematic gaming. Other findings point to unintended consequences, such as restrictive mediation inadvertently increasing gaming frequency or deceptive behaviours among adolescents [10], as noted in the study, hinting at potential boomerang effects. Furthermore, gender differences in gaming patterns and control perceptions, alongside external influences like peer networks [20], further complicate the relational landscape.

Theoretically, these findings challenge traditional parental mediation models, which typically categorize strategies as restrictive, active, or co-use. The range of identified approaches, such as gatekeeping (regulating access), discursive mediation (critical discussions), and investigative efforts (seeking information), proposes a refreshed parental mediation framework [21]. The emphasis on relational quality over mere control aligns with self-determination theory, which posits that autonomy-supportive parenting enhances intrinsic motivation and well-being, while authoritarian styles may breed resistance. Moreover, integrating gaming into family life as a shared activity, rather than a source of conflict, calls for theories to consider its social and cultural dimensions, moving beyond a deficit-focused view to recognize its potential as a relational tool [22]. Practically, the review advocates for a balanced approach to parental control, blending clear boundaries with opportunities for engagement. Parents should be encouraged to transcend their regulatory role and embrace participatory strategies, such as playing age-appropriate games or discussing their content, to transform gaming into a conduit for family connection. Educational initiatives, such as media literacy programs, could equip parents with tools to navigate gaming’s risks and benefits, fostering informed decision-making over fear-driven restrictions [29].

Game developers and policymakers also have a role in enhancing rating systems and integrating parental oversight features, such as time management tools or content filters, to bolster mediation efforts [41, 42]. Moreover, we cannot deny that the role of interventions, like informational guides, may need tailoring to families already grappling with gaming-related issues, as broad preventive measures show limited effectiveness [40]. The studies’ conclusions and recommendations converge on several core themes. A consensus emerges on the need for nuanced, context-sensitive strategies that account for the child’s age, gender, and cultural context [17]. Many studies advocate promoting media literacy and parental training to shift from reactive control to proactive guidance [19], while others propose balancing gaming with other activities to preserve family harmony [22], and some caution against over-reliance on restrictive measures due to their potential to strain relationships and provoke conflicts in the familial climate [30]. Together, these insights suggest that effective mediation hinges not just on what parents do, but on how they do it, prioritizing communication and relational warmth over coercion.

Looking forward, future research should prioritize longitudinal designs to track the evolving impact of mediation strategies on family relationships over time [30, 42]. Exploring how these approaches adapt to developmental stages, particularly adolescence, could illuminate age-appropriate practices [28]. Cultural variations also merit deeper investigation; differences in control practices and relational outcomes between countries, such as restrictive tendencies in China [24] versus integrative approaches in Norway [22], indicate that global models must be locally adaptable. The role of external factors, like peer networks [20] or institutional policies (e.g., school regulations), also warrants exploration to situate parental efforts within wider social ecosystems. Finally, as proposed in a study, examining gaming’s potential to fortify family bonds, rather than merely disrupt them, could redefine its role as a space for negotiation and connection in the digital age [22]. In sum, this systematic review underscores the intricate interplay between video games, parental control, and family relationships. While restrictive measures dominate, their relational costs necessitate a shift toward interactive, autonomy-supportive strategies that leverage gaming’s potential to strengthen ties. By adopting a nuanced, relational approach, parents can navigate this digital landscape in ways that mitigate risks while fostering resilience and closeness within the family unit.

5. LIMITATIONS OF THE STUDY

This systematic review has some limitations. No studies from African or Arabic contexts were identified or included, which limits the cultural applicability of the findings. Additionally, the developmental stages of children, which can influence parental strategies, were not adequately considered. Finally, most studies failed to account for gender and cultural differences, reducing the depth and nuance of the analysis.

CONCLUSION

This systematic review highlights the complex interplay between parental control, children's video game use, and family relationships. While restrictive measures like time limits and content bans are prevalent, driven by concerns over addiction and harmful content, they often lead to negative relational outcomes, such as conflict and secrecy. Conversely, interactive strategies like active mediation and co-playing, though less common, foster improved family cohesion and communication. Parental attitudes significantly shape these approaches; those viewing gaming as a threat favor restriction, while those recognizing its potential for bonding adopt more participatory styles. The effectiveness of control is not by the actions themselves, but by the manner in which they are implemented, with autonomy-supportive styles yielding better child adjustment and fewer conflicts.

Practically, these findings advocate for a balanced parental approach that blends clear boundaries with active engagement. Parents should be encouraged to move beyond mere regulation, embracing participatory strategies like playing age-appropriate games or discussing game content to transform gaming into a conduit for family connection. Educational initiatives, such as media literacy programs, are crucial to empower parents with informed decision-making tools, shifting from fear-driven restrictions to proactive guidance. Furthermore, game developers and policymakers have a role in enhancing rating systems and integrating parental oversight features, like time management tools, to bolster mediation efforts. Tailored interventions are also vital for families already facing gaming-related issues.

Future research should prioritize longitudinal designs to track the evolving impact of mediation strategies on family relationships across developmental stages, particularly adolescence. A deeper investigation into cultural variations and gendered patterns in control practices is also warranted, acknowledging that global models require local adaptability and flexibility. Exploring the influence of external factors, such as peer networks and institutional policies, will further contextualize parental efforts within broader social ecosystems. Finally, examining gaming's potential to strengthen family bonds, rather than solely disrupt them, offers a promising avenue to redefine its role as a space for negotiation and connection in the digital age, promoting autonomy-supportive, relational mediation.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: conceptualization: NT; visualization: OBR; analysis and interpretation of results: MF. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| WOS | = Web of Science |

| CASP | = Critical Appraisal Skills Programme |

| IGD | = Internet Gaming Disorder |

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

All articles cited and discussed are publicly available online through open-access sources, author-provided full texts, or accessible databases.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the PhD director, the academic advisors, and colleagues for their valuable guidance throughout this research. They would also like to thank peer reviewers for their constructive feedback. This work was conducted as part of doctoral research in education, video games, and sports science.