All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

The Effects of a Knowledge Management Skill Development Program (KMSDP) on the Holistic Health Promotion Knowledge Management Behaviors of Muslim Women Leaders

Abstract

Background:

Women have high average life spans and live longer than men. In Thai-Muslim society, women have the role of caring and promoting the health of everyone in their family, such as preparing food, raising the children, and taking care sick persons so they are required to be leaders for promoting health in the family.

Objectives:

To develop a KMSDP and to study the effects of using a KMSDP for knowledge management behaviors regarding holistic health promotion by Muslim women leaders

Methods:

This research is of an exploratory sequential mixed-methods design. The researcher analyzed the qualitative data and SECI concept to develop the KMSDP. The quantitative data were applied to test the program using a pre-test and post-test design. The participants were randomly assigned to the experimental group (n=35). Descriptive statistics and independent t-test were used for the data analyses.

Results:

The qualitative findings indicated three themes applied to create the program: 1) To be in accordance with the Muslim way of life; 2) To conform to rubric religious principle; and 3) To agree with family leaders. As for the effects of the KMSDP on the holistic health promotion knowledge management behaviors, it was found that the post-test mean scores for knowledge, management, and skills were higher than those for the pre-test mean scores at a statistical significance level of .001.

Conclusion:

Healthcare providers, proactively promoting health in the Muslim community, can apply this program to develop Muslim women leaders for holistic health promotion.

1. BACKGROUND

The Muslim community is prominently characterized by extended families with sound family relationships. Children and grandchildren that marry remain in their original families, which expand into a larger community with the features of a family-oriented society [1]. Additionally, in the Muslim family, women have the duty to care for the family’s health and prepare food for everyone in the family. From the previous study [2], it was found that Thai Muslims are becoming ill with inappropriate consumption behaviors and a lack of sufficient exercise. They have diseases, such as high blood pressure, high cholesterol, diabetes mellitus, and heart disease and obesity at higher rates than Thai Buddhists. These conditions are found to be more prevalent among females than in males. Additionally, Thai Muslims consume salty foods, fat-rich foods, and fried foods in the starch and sugar groups in daily life [2, 3]. These items have adversely impacted the health of Muslim people.

Women have high average life spans and live longer than men, and, in Thai society, women have the role of safeguarding and promoting the health of everyone in the family, the promotion of sound health thus requires the leader to build a health network that could be implemented as a strategically-important means of communication, conveying both knowledge and guidelines to women. They can then relay their experiences to one another for the promotion of their own holistic health.

The Thai nation’s policy has realized the importance of health problems and social equality for every age group. Health literacy is important for changing the behavior of people. Knowledge which is well-known as “tacit knowledge” or “explicit knowledge,” the former referring to the knowledge of the individual that develops from her accumulated experiences and behaviors [4]. It is characterized by specific attributes that emanate from inside. This tacit knowledge cannot be enhanced in any way, whether it is being exchanged, shared, or transferred for use by others. People contribute a mix of tacit knowledge blended with the explicit knowledge for which there are records in the form of documents, annals, and knowledge that can be distinguished from actual practice. Processes such as these are referred to as knowledge management (KM) or, alternatively, the “sprouting” of existing knowledge, outputting the desired product through a leader whose management brings it to the surface. This form of management helps a certain number of women that are in good health to help themselves, or to acquire experience in the promotion of health among themselves. It also helps them to develop themselves continually as leading figures in the area of holistic health promotion.

The researcher team developed a program based on the knowledge exchange concept and the SECI model [5] that stresses lifelong learning, practicing, and a learners’ center. The KMSDP emphasizes health-oriented research studies in personal lifestyles and acknowledges the need for developing leadership roles for Muslim women regarding their own health promotion. It applies qualitative data to develop the original program so that it may find acceptance and be implemented efficiently with good results, ultimately benefitting the women and people of the Muslim community. When Muslim women develop into health-promotion leaders, it can be expected that these women will build good states of family happiness that will help to connect to their communities.

2. RESEARCH OBJECTIVES

The objectives of the present research were to develop the KMSDP and to study the effects of using the KMSDP for knowledge-management behaviors regarding the holistic health promotion of Muslim women leaders.

3. RESEARCH HYPOTHESIS

The sample group under study demonstrated higher levels of health promotion knowledge-management behaviors after entering the program than before entering the program, with a statistical significance level of 0.5.

4. CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

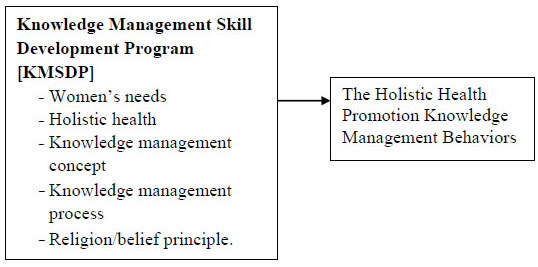

The SECI model of knowledge management and the qualitative data were applied to develop the KMSDP [5]. It consisted of five components: women’s needs, holistic health, the knowledge-management concept, the knowledge-management process, and the religion/belief principle. The researchers reviewed the relevant concepts, theories, and literature, and present a conceptual framework as follows (Fig. 1).

5. METHODS AND MATERIALS

This research is of an exploratory sequential mixed-methods design [6, 7]. The qualitative data were collected until saturation with 24 informants that were selected using the purposive and snowball sampling technique and analyzed using the content analysis. Then the researcher applied the qualitative data and SECI concept to develop the KMSDP. The effects of this program were examined regarding knowledge-management behaviors in relation to the holistic health promotion of Muslim women leaders in the Muslim community by comparing the pretest and posttest mean scores. Simple randomly assigned to the experimental group (n=35). Descriptive statistics and independent t-test were used for the data analyses.

5.1. Research Tools

1) An interview guideline was created by the researchers to be used as a guideline in interviewing the Muslim women and Muslim religious leaders. The interviews referred to the acceptance of Muslim women to be a health leader as a role and function in the lifestyles of people in the Muslim community and the appropriate conduct of women.

2) The holistic health questionnaire, Knowledge of KM questionnaire, and KM skill evaluation: The questionnaires were adapted by the researchers from the holistic health questionnaire of Othaganon and Kongvattananon (2018) [8], which has been used with leading figures among the elderly with a reliability of .79, .82, and .84. Further, after the participants received the questionnaires that were compatible and could be applied within the Muslim context, they tried them out and they showed a statistical Kuder-Richardson 20 of .81, .87, and .80 among a total of thirty questions, twenty-six questions, and seventeen questions respectively.

3) The KMSDP program: This program used in this research was developed from the SECI model (knowledge exchange theory). The program incorporated the religion/belief principle, and knowledge and desires that have relevance within a Muslim context. It consists of the following components: project name, objectives, program architecture, method, training topics, and training management concepts. The length of time devoted to the training was a total of 48 hours.

The KMSDP program was constructed according to the following steps:

1) The researchers interviewed the needs and beliefs of the Muslim population in the areas of health status, holistic health promotion, and health promotion knowledge-management awareness. We used the qualitative data to produce a training curriculum that incorporated both the substance and cultural sensitivity of Muslim beliefs and lifestyles.

2) A comprehensive training curriculum committee was formed comprising a total of five people: a physician, a professor in nursing, a nurse, a Muslim leader, and a community leader. The data under study were obtained from various contexts pertaining to the Muslim community and the environment in which the study took place, from the actual practice of Muslim religious principles, and women-centered learning and from their lifelong learning. Measurement tools were subsequently applied to conduct tests with other groups and other populations, numbering thirty people. The tools implemented were again adapted for compatibility. After adapting the tools and the program, it was tested with thirty participants in other Muslim communities, and the program features were as follows.

The KMSDP program for Muslim women leaders required 48 hours in 12 training sessions of 4 hours each. It consisted of 1) information content (Muslim community health promotion in the area of holistic health, information management, and a knowledge-management process); 2) a knowledge exchange process (extending tacit knowledge to explicit knowledge); 3) learning from actual practice (a community garbage management project); 4) learning from other people (a learning exchange with female leaders in other communities); and 5) a learning results summary and expanding upon it.

5.2. Voluntary Protection of Rights

The researchers requested certification of research ethics and received certification from the third convening of the Subcommittee of the Institutional Review Board, health science branch, Thammasat University, prior to qualitative data collecting and the program used in the research, code 211/3560. First certification was granted for the period of January 27, 2017 to January 26, 2018. The second certification was granted for the period of January 27, 2018 to January 26, 2019. The participants gave informed consent before interviewing, joining program, and the report was permitted for public.

5.3. The Population and Sample Size

The population consisted of Muslim women 20 years of age and older that resided in the Muslim community under the study area in Pathum Thani Province, Thailand.

In the qualitative study of the sample group, the major pieces of information were received from Muslim women aged between 25 and 71, who were willing to cooperate in this research, and community leaders/Islamic religious leaders in the community. Purposive sampling was employed in the selection of the major informants from the community population. The members of this population were open to conversation and provided information from the outset. They began by voluntarily entering into the group conversation and were gladly cooperative. Those supplying the information were selected using snowball sampling for the sake of diversity. Appointments were set for the convenience of the volunteers for the purpose of group conversation. The time expended was approximately one to two hours per group, supplying an ample amount of information and saturated data. Twenty-four informants comprised the total of 21 women and 3 community leaders.

The sample size for the quantitative study was calculated using the formula of Schlesselman (1982), which yielded a minimum group size of 28 people in order to forestall a complete diminution of respondents during the course of the study. According to the principle of Pholit and Hungler (2008) [9], the sample groups increased by 20%. Appropriate sample-group sizes were calculated, with a minimum group size of 35 people. Selective criteria in making the selections resulted in participants that were 20 years of age and older. Of particular interest were the health promotion leaders, who were Muslim women that had registered in the region of the Muslim community in the study area for at least three months and were capable of communicating in the Thai language.

6. RESULTS

6.1. Results of the Qualitative Research Study

The results pertained to the perception of health, lifestyles, and the desires of Muslim women regarding the promotion of holistic health. The informants included a total of 24 respondents, among whom 21 were women. They supplied information through the focus group method. Others were three men-a religious leader, an elderly member of the community, and a religious instructor-that confirmed the data. Data collection was done by focus group and in-depth interview. The main contributors of the data alluded to the confirmed accuracy of the data using the triangulation. The issue was to improve the program by designing it prior using it, keeping in view that it should harmonize with the lifestyles and principles of religious practice. Activities for women who are family leaders had to receive their approval. The sample groups defined health problems in the community, such as chronic disease, including obesity, diabetes, high blood pressure, and high blood cholesterol; the accumulations of garbage and other waste in the community creating a problem from the resulting filthy foul that spreads throughout the community.

The qualitative findings demonstrated three themes that the Muslim women perceived to be necessary for effective holistic health promotion leaders:

1) To be in accordance with the Muslim way of life, as can be seen in the following statements.

“Grooming for the researchers consisting of full suits of clothing, and putting an end to wearing shorts or sleeveless shirts each and every time when entering the Muslim community.”

“Carrying out the activities on time and leaving on time, by scheduling the activities in the afternoon after Muslim worship services and leaving before the evening worship.”

“In carrying out any activity, avoid any interference with Muslim worship practice, or simply stop whenever there is a community merit-making event in progress.”

2) To conform to rubric religious principle, as three of the participants indicated, one woman and two leaders.

“Be careful in carrying out any activity that conflicts with the practice of their religious principles. In particular, avoid foods that are forbidden for consumption. Likewise, be careful in your speech when conversing, and prepare foods which bear the Halal seal, or order foods from a Muslim store on the scheduled day of the activity.”

“Arranging group activities; putting a halt to activities that involve loud noises or any use of musical instruments and singing; setting up games that can be played within the space of a room, such as mind-stimulating game, project writing, and joint community activities.”

“If, during the course of an activity, the sound of an Al-Quran incantation can be heard, stop the activity and remain quiet. Be alert to this sound on any occasion of a community activity and put a complete halt to activities during the time of fasting in Ramadan.”

3) To agree with the family leader, as indicated by all of the women and the three leaders.

“Married Muslim women can go out of after her husband permitted her to join. Family leader permitted Unmarried Muslim women to join the activity.”

Modifying activities to harmonize with the needs of Muslim women so that they do not conflict with religious principles or community practice acceptance that has been in effect for some time already, and exercising caution in exhibiting behaviors to which Muslim groups might be sensitive, will help Muslim women and their community have a favorable attitude toward the activities. To do so will aid in the efficiency of the KMSDP program for holistic-health promotion and the women will be more knowledgeable as a result—they will possess good knowledge-management skills in the form of health promotion knowledge-management behaviors that will be at a higher level after joining the program.

6.2. Results of the Quantitative Research Study

Concerning the results of implementing the KMSDP program, this program can be applied to knowledge-management behaviors that are related to the holistic health promotion of Muslim women leaders in their Muslim communities.

Thirty-five participants willingly joined the research and underwent the training completely as specified. The ages of the sample group ranged between 23 and 72 years, while most were 60 years of age and older. Most of those in the age range of 41 to 50 years were married. Fifty-four point three percent lived in an extended family and the majority of them had only an elementary education. The occupation of 74.3% of them was found to be that of a housekeeper or housewife. Fifty percent of them had an income between 1,001 and 10,000 baht. Eighty percent, nearly one half of them, lived on an insufficient income. As many as 68.6% had membership in a community. Most of them were a housekeeping group and a public health volunteer.

As for the effects of the KMSDP program on the holistic health promotion knowledge-management behaviors, it was found that the post test mean score for knowledge of holistic health, knowledge of KM, and the KM skills of the Muslim women leaders was higher than the pretest mean score at a statistical-significance level of .001 as follows.

1) The mean score for the knowledge of holistic health, achieved prior to participation in the KMSDP program, was 18.57 (SD = 4.55). The mean score after participation in the program was 26.60 (SD = 3.17). After testing with the statistical t-test, the mean score for the knowledge of holistic health of Muslim women leaders was higher than it was prior to participation in the program, with a statistical significance (t = -9.98, p < .001).

2) The mean score for the knowledge of KM management, prior to participation in the KMSDP program, was 19.54 (SD = 3.10). The mean score after participation in the program was 23.69 (SD = 1.81). After testing using the t-test, it was found that the mean score after the participation of in the program for Muslim women leaders was higher than it was prior to their participation in the program, with a statistical significance (t = -7.63, p < .001).

3) The mean score for knowledge-management skills in the area of health promotion, achieved prior to participation in the KMSDP program was 3.63 (SD = 2.03). The mean score for knowledge-management skills, after participation in the program, was 14.89 (SD = 1.62). After application of the t-test, it was found that the mean score for knowledge-management skills after participation in the program was higher than it was prior to participation in the program, with a statistical significance (t = -23.77, p < .001).

7. DISCUSSION

The results of the study on the states of health of Muslim women showed that a majority of them have chronic diseases. In the Muslim family, women have the duty of caring for the family’s health and preparing food for everyone in the family. The prominent feature of the Muslim community is the extended family, with good family relationships. Even after marrying, children and grandchildren remain in their original families, which then expand into larger communities; these communities will accordingly show the features of a relative society [1]. Contrary to the study, however, was the discovery that the sample group contained single families alongside the extended families, probably because the communities under study were located in urban areas. Children and grandchildren are increasingly separated from their families to form single families, and some of them are finding work outside their communities. Additionally, from the previous study [2], it was found that Thai Muslims that are obese and that have chronic diseases derived from inappropriate consumption behaviors. Further, they are not getting enough exercise. As a result, they have high blood pressure, high blood cholesterol levels, diabetes, heart disease, and obesity at rates greater than Thai Buddhists [2]. These problems are more prevalent among females than males. In addition, it was found that Thai Muslims are fond of consuming salty foods, fat-rich foods, and fried foods in the starch and sugar categories [3]. Further, Thai Muslims are fond of eating sweets and fat-rich foods, in the mistaken belief that foods of this type are actually good for them [2, 3]. Yet, these things still affect the states of health of Thai Muslims, and not for the better. These findings are consistent with the results of the present research, where it was seen that 80% of Muslim people are obese, followed by those that have diabetes, high blood pressure, high blood fat, and asthma and allergies.

As regard the research results from the intervention section, the hypothesis can be accepted that Muslim women in their communities within the District of Khlong Luang exhibit higher-level “knowledge-management behaviors in the area of health promotion” following their training than they did prior to the training, with a statistical significance (P < .001). From these research results, it was found that their average knowledge scores in the areas of holistic health, knowledge management, and knowledge-management skills after participation in the KMSDP program were higher than they were prior to their entrance into the program, with a significance (P < .001). This result can be explained by the KMSDP program for Muslim women leaders, which was developed from the training curriculum for older adult leaders in the Province of Chonburi, and which has since been implemented in one of the communities in the District of Khlong Luang [8]. In the present research, the curriculum was modified in order to adapt it to a Muslim context and to conform it specifically to females. The curriculum was modified for these purposes by applying the behavioral principles of the Islamic religion that Muslims follow in their day-to-day lifestyles [10]. Activity management was modified in three ways: to be in accordance with the Muslim way of life, to conform to rubric religious principle, and to agree with the family leader [11, 13]. This program was accepted by Muslim women, their family, and the religious and community leader.

Adapting the activities to harmonize with the needs of Muslim women, avoiding any conflict with their religious principles or community lifestyle that they have thus far been following, and being careful of any display that a Muslim would find offensive will help Muslim women and their communities appreciate the positive aspects of the activities. The Muslim women leadership development program on holistic health promotion will, as a result, become more efficient. The women themselves will then have a greater store of knowledge, as well as good knowledge-management skills in the form of health promotion knowledge-management behaviors that will be at a higher level after joining the program. In this sense, it can be seen that the KMSDP program was effective in developing Muslim women leaders in terms of holistic health promotion.

Moreover, the key principles stemming from this research are being applied jointly to generate the acceptance of female leadership in Muslim group settings. Specifically, the acceptance issue involves what is called “gender sensitivity” [14, 15]. It especially applies to the authority relationship and role between men and women, which affects the way people act in their everyday life [16, 17]. The acceptance issue also involves what is known as “cultural sensitivity” [18, 19]. Planning curriculum activities to be compatible with the needs and desires of Muslim women enables Muslim women to join the training program with the permission of their husbands and family heads. In this way, women find a sense of contentment and become interested in what they are learning because there is no conflict with their religious practices and beliefs. In addition, everyone becomes more knowledgeable.

An atmosphere of learning, everyone is equal, and every comment is regarded as being equally important. The capacities of women are drawn out to lead their groups in joint activities. Examples of such activities include standing in front of the classroom as a group representative to express an opinion or to respond to any questions there may be; and campaigns to limit the amount of trash in the community [20, 21]. Participation of this sort causes every woman that joined the research group to see herself as a person of worth and to gain acceptance. She is benefitting her own community, and this takes place through the principle of instilling power and authority in the woman, or what is known as “empowerment.” This empowerment manifests a person’s inherent capabilities, a matter in which many women feel they are inferior [22, 23]. It draws out one’s embedded knowledge, or “tacit knowledge,” to become one’s overtly-discernible knowledge or “explicit knowledge” [5, 24]. It also induces Muslim women to develop a sense of pride in themselves, and ultimately it empowers this program to develop health promotion leadership behaviors.

SUGGESTIONS AND CONCLUSION

Proposals for applying the research results are as follows.

1. In the area of health promotion nursing, nurses are capable of applying the KMSDP program to develop Muslim-women leadership in other regions or if it is applied to the development of women leadership in other groups, consideration should be given to the context and similarities of the population. To do so will help increase the efficiency of the program.

2. As regard the research, the efficiency of the Muslim women leadership development program should be studied, modeled on a double-group comparison of the experimental group with the control group. This approach will be useful later.

3. The results derived from this study have shown that, in the development of any program, developing only from theory is not sufficient studying in some context or location, and incorporating an understanding gained from the opinions and needs of the involved individuals into the development, will promote increased efficiency in the use of the program.

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

The researchers received certification from the third convening of the Subcommittee of the Institutional Review Board, Health Science branch, Thammasat University, Thailand (code 211/3560).

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

No animals/ humans were used for the studies that are the basis of this research.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Informed consent was obtained from all the participants prior to data collection.

FUNDING

This research has received support funding from research funds of the Faculty of Nursing at Thammasat University (09/2016).

CONFLICT OF INTERSET

The authors declare no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Accordingly, the researchers wish to express their thanks at this point. Additionally, we are indebted to all the Muslim women leaders and community leaders that participated in this study.