All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

A Narrative Review of the Disenfranchisement of Single Mothers in Highland Ecuador

Abstract

Background:

The Andean South American country of Ecuador presents social challenges that contribute to inequities. The social determinants of health have impacts on the physical, psychological and social health of individuals across all societies. Ecuador is an example of how the interactions of gender roles and social determinants of health impact the health of single mothers and their children.

Methods:

A retrospective historical literature review was conducted on gender role expectations within the rural context Ecuador to inform future public health strategies and health interventions.

Results:

Gender inequality contributes to higher rates of single parenting, child labour, and migration. Food insecurity and poverty are affected through the interface of economic hardships and rural agricultural livelihoods.

Conclusion:

The disenfranchisement of poor rural women in Ecuador is deeply rooted in historical gender discrimination, societal attitudes, and institutionalized gender bias that incur onto the society as a whole in terms of becoming less protectors and producers of human resources. The health of single mothers and children living in poverty and their ability to create a healthy family environment will not improve until women explore their productivity and creativity amid social tensions and livelihood struggles.

1. INTRODUCTION

Worldwide, 320 million children live in single-parent households headed by single mothers [1]. In Ecuador, of 4.3 million homes, 1.1 million (26.4%) are female-headed households [2]. Single mothers play important roles in caring for and feeding their children in impoverished rural areas where access to healthy food is not always available [3]. Additionally, mothers’ economic hardships impair access to quality foods, leading the most impoverished children to consume cheap industrial foods high in sugar, salt, and fat, but lower in nutritional value [4]. Mothers with a large number of children often find it economically necessary to have children take on more family work responsibilities, including working in the home or participating in the labour force outside of the home [5, 6]. Children who must work due to family size are denied their right of access to education which can lead to limited workforce diversification, beyond the farm, in the future.

It is estimated that 9% of Ecuadorian children and youth between the ages of 5 and 17 years are engaged in paid labour, with 62.8% being male compared to 37.2% female [7]. As a result, children as young as 10 years old acquire adult responsibilities which prevent them from studying or participating in play activities [5, 6]. Both education and play make important contributions to the quality of life and future health of children, and therefore, early engagement in unpaid and paid labour is a mechanism for perpetuating poverty in Ecuador. Cultural norms dictate that most single-parent families are led by women who struggle with food insecurity and poverty with limited access to avenues of empowerment in education and political involvement.

The important contributions of women to their rural communities are closely related to their unpaid work and are negatively affected by the lack of education and their occupation in paid roles [8]. Ideological positions placed women at home, limiting their educational foundations and labour force skills which prevents them from entering the paid workforce. The impact of gendered role expectations independently affects women in Ecuador. For example, the socio-economic status of women can be illustrated through the internal household consumption in the family:

A poor woman cooking barley and water and a rich woman whose cooking pot contains barley, mutton, carrots, and onions are utilizing the same structure in their cooking, one prepares a minimal and impoverished, the other a maximal, full-blown version of the same cultural correct dish [9].

The gender role expectation is a life dominated by household chores, as men are not expected to contribute to the home or childcare. These activities account for 17% of a woman’s work day, compared to only 1% of a man’s work day [10]. Nurturing and caring work define the experiences of single mothers in Ecuador. It is not uncommon for a woman between 20 and 30 years old to have two to four children with multiple fathers, none of whom live or interact with the woman or the children, as the societal attitudes do not foster the role of fathers to care for and feed their children [11]. Even in these situations, single mothers are expected to be nurturing and diligent women who provide food and care for their children. In fact, the size of the family amplifies the challenges that lead women to have insufficient means to ensure their children’s livelihood [12]. Inadequate income further hinders mothers’ ability to get enough food for their children, potentially leading to poor health outcomes because of nutritional deficiencies.

The life roles and challenges of single mothers are crucial factors that influence health and quality of life in all countries, with the cultural context further influencing determinants and outcomes. The historical context of how Ecuador became a middle-income country has contributed to societal values about the roles of women. Impoverished mothers dwelling in rural areas often suffered from the inequities of food insecurity and poverty experiences [13]. The impact of household tasks and childcare leaves little opportunity for Ecuadorian single mothers to participate in education and political processes that are not readily accessed in rural areas. This marginalization can be challenging as interventions to improve health or well-being are often less likely to reach those who are marginalized.

Public Health strategies have to consider the context in which individuals, families, and communities aim to achieve health. While much research focuses on the North American context, this knowledge is not always easily adaptable to other contexts. Understanding how context affects health behaviours and outcomes is important for adapting interventions and policies and creating those that uniquely address the needs of specific populations. In this view, a retrospective historical literature review was conducted to identify specific concepts underpinning the on-going disenfranchisement of poor rural Ecuadorian women in the global south. The goal of this narrative review is to explore how gender inequality and gender role expectations placed the majority of the burden of poverty in rural agricultural livelihoods in Ecuador on single mothers and children.

2. METHODS

Two types of knowledge sources were examined in this literature review: books and journal articles. Firstly, book-based resources were reviewed if they: (1) presented the historical and political processes of Ecuador; and (2) identified gender roles in rural agricultural livelihoods in Ecuador. Secondly, academic journal articles were selected with text written in English if they: (1) were based on gender and food poverty within the Andean South American context (Venezuela, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, and Bolivia); and (2) included single mothers and children. Studies outside the Andean context were excluded.

For the first round of reviews, a library search at the Western University encompassed a purposeful approach to identify physical books that investigated key social processes of the Ecuadorian context and the historical construction of gender roles during the late 19th century and early 20th century. Secondly, we performed a search in five electronic databases: Medline (Ovid), Embase, Web of Science, CINAHL, and Scopus from 1990 to 2020. A review of the grey literature was also conducted through the Google web engine in which we included Spanish online sources.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Historical Context and its Impact on Women

The historical perspective about how Ecuador evolved as a country informs the context in which women were situated in roles of nurturance in the late 19th century [14]. Gender roles and how they evolve over time contribute to current gendered expectations for women’s roles in relation to domestic duties and childcare. During the late 19th century (1860 - 1895), intensive work on the farms further affected the family environment through high rates of domestic violence [15]. The Ecuadorian government did not draw any attention to husbands’ abusive behaviour from court cases of domestic violence. In fact, state officials responded that women were the contributors to domestic violence rather than the victims [14]. This resulted in the continued abuse and impoverishment of women and forced others to flee or separate from their partners to better their disadvantaged status [14].

Ecuador is an illustration of dominant gender roles that shape the evolution of society. Highland landowners directly controlled agricultural labour through debt peonage in order to grant access to land [10]. Poor families who subsisted on agricultural farming had to work in large plantations while generating debt with landowners [10]. This colonial practice was abolished in 1857 and not only affected poor families, but also informed gender roles [14]. Although the bonded labour ended, landless families were powerless because fields belonged to others, and women were mainly responsible for feeding their families. Gender role expectations characterized women’s duties as belonging at home due to their nurturance [14]. Women’s obligations to the family became a woman’s identity, with primary responsibilities of food preparation and child-rearing. Women were unable to contribute to national discourse due to the burden of home and family responsibilities, which ultimately made them politically vulnerable and unable to promote empowerment. Thus, the evolution of infrastructure, social supports and social policy was primarily driven by men and continued to ignore the needs of women and their children.

The early 20th century (1895 - 1925) saw concentrated efforts to enhance children’s welfare in Ecuador. Institutionalized care, material support, and medical assistance were the priorities of state interventionists to secure the well-being of mothers and children. Three major institutions were opened in Quito, the capital of Ecuador: Junta Nacional de Beneficencia (1908) managed the birth and infant clinic; Sociedad Protectora de la Infancia (1914) assisted single mothers with insufficient means for children’s care; and Sociedad de Señoras de la Gota de Leche (1919) established hygiene centres for breastfeeding, sterilized milk, and medical control for babies [11]. The engagement in shaping national responses to child-rearing struggles among Ecuadorian single mothers mainly depended on political preferences [15]. Although the Ecuadorian government had implemented child protection programs in the past, they were not effective because of a lack of monitoring or the consideration of women’s actual daily lives, which represented a form of disenfranchisement.

The cycles of poverty and subjugation continued as priorities were set based on political interests through government rotations and there was significant political instability and turnover [16]. The government action to enable women to vote in 1929 was intended for men to retain their power in the government [17]. Thereafter, the government’s focus was to build an export economy based on plantations and the expropriation of land from the catholic church [9]. Inequalities continued throughout this period. By 1954, owners continued to hold land with only 6% of white families owning 80% of the land [10]. By 1964, there was a small transition of land ownership to poor families through the agrarian reform, but this government law transferred land from men to men and required laborers to dwell and farm on the same plot of land for at least ten years [14]. Women did not benefit from these changes as they were not identified for roles in land productivity nor seen as land owners. This historical context had long-lasting impacts on the status of women with a lack of power in society.

3.2. Political, Social, and Economic Factors

Ecuadorian society was shaped by the ever-evolving flux of governments that clearly influenced the concept of gender based on ideas and practices deeply embedded in assumptions about the roles of women in society [14]. One such assumption was that men dominate through dynamics of power [18]. Political standpoints highly influenced ideology on gender profiles: “ideology constructs what we can say about living, and hence how we experience our lives” [9, 19]. Within the political structure in Ecuador, male dominance was constructed to increase men’s visibility in state making, while undermining women in spite of their community roles. In this sense, the political structure of Ecuador creates structural debasement with respect to women and political life because their status in society is weak and powerless. This results in a continuous structure of corruption rooted in culture and historically based systems. The rotation of governments ultimately diminishes public health, children’s education, and the potential of women to become more competitive and productive in the society.

The Ecuadorian society failed to recognize corruption in peoples’ choices and policies that diminished the potential for humanity, resulting in the growth of impoverished people from 3.9 to 9.1 million between 1995 and 2000. This represented 34% to 71% of the total population, respectively [18]. As a result, the government introduced the U.S. dollar into the economy in the year 2000 which replaced the Sucre Ecuador’s national currency in 2000 with the goal to decrease transaction costs in international trades [18]. After this change, there was a great migratory wave — 1.5 million Ecuadorians were residing in Europe and the United States in which their remittances to Ecuador represented the second largest source of revenue for the government. As migration trends were concentrated mostly in males, it resulted in changes to family composition where men were less likely to participate in raising their children [18], which resulted in drastic changes to family composition. Furthermore, there was an increase in the number of single mothers heading households and caring for children, who were referred to as custodial mothers [19]. As such, Ecuador is characterized as a gender-based society where women are more likely to take accountability for caring and feeding their children.

After a long period of commodity exports, Ecuador became a middle-income country in 2008 [20]. The government revenues supported education for women through access to universities at no-cost in urban areas, which in turn were the main socioeconomic drivers for development, along with commercial agro-exports in the coastal region and oil exports in the Amazon region [14]. The new political and socioeconomic system developed in Ecuador was characterized by decentralization of the state, however, it was still subject to change according to government rotations and location [20]. The political structure showed a strong bias with respect to women’s issues, with few programs structured by the government to provide women the opportunity to access education in the midst of their tensions and rural livelihoods [15].

3.3. Food Insecurity and Poverty

Vargas and Penny [21] summarized the common approaches to quantifying food insecurity applied across the Andean South American context: 1) balancing household food consumption; 2) calculating income and expenditure surveys; 3) measuring energy intake based on the frequency of meals according to the recall method; 4) measuring the nutritional status of children; and 5) analyzing people’s perceptions about poverty, food insecurity and hunger. The role of gender is notably absent in these thematic areas. There is a lack of focus on how gender inequality affects food insecurity. This is remarkable given that risks and outcomes are clearly gendered.

Food insecurity is an on-going problem in Ecuador, which compromises the growth of children. The fact that food insecurity can lead to undergrowth illustrates the complexity and importance of this issue. To highlight this important relationship, stunted child growth and low weight have historically been recorded among children of women who are parenting alone in low-income rural households [22]. The lack of economic resources hinders a mother’s ability to make healthy choices, even if the mother has adequate knowledge about healthy behaviours [12]. In this view, the daily basic needs of mother-child are unfulfilled, evidenced by the growth of their children.

The US Agency for International Development (USAID) described food availability as the ability to obtain sufficient quantity and quality of food that meets nutritional requirements for all household members [23]. In rural households, poor nutritional outcomes were associated with low diversification of food quality. For example, potatoes and wheat are the primary food consumed [21, 24, 25]. Geographical barriers, such as long distances to reach markets, contributes to the low diversity of foods [6]. Poor access to healthy and safe food can negatively affect children’s physical, emotional, educational, and social development, leading to chronic malnutrition [5]. More specifically, children remain malnourished due to the inability to access nutritious foods that further their experiences of hunger.

Ecuador is a cash-based society where commodities of foods are acquired through local market systems [12]. However, the initial agrarian system in late 19th century Ecuador left conditions of grinding poverty, such as in Zumbagua where farmers had neither a market for economic profits nor economic means to invest [9]. The working conditions were poor, but farmers had no choice to work for survival to receive land resources and cash [9]. Cash was rarely paid since poor families held debts with wealthy highland landholding families who generally maintained ideological, economical, and political state domination [14]. In the same way land owners exercised subjugation over male farmers, male farmers practiced the same subjugation over their wives [14]. This historical system eventually led to the impoverishment of men and institutions as the result of women experiencing exploitation, marginalization, violence, and powerlessness.

3.4. Rural Agricultural Livelihoods

Women represent 25% of agricultural labour in South America and their interdependence with local biodiversity and food resources are widely recognized [26]. Women spend most of their time growing food in the fields while also cleaning, drying, winnowing, threshing, sorting, and storing the family crops. This can result in exhaustion because of the combined family role and farm work responsibilities. Additionally, this division in their time negatively impacts their children and families. Mothers described that carrying out agriculturally productive tasks resulted in less food preparation; with increases in the amount of cultivated land increasing the number of caregiving barriers related specifically to time constraints [27]. As such, it is noted that there is a necessary trade-off involved between time devoted to agricultural gains and food preparation.

As some families can only acquire small plots of land due to past government reforms, small-scale agriculture continues to be the main method to alleviate hunger among matriarchal Andean communities [28, 29]. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations [30] found that 50% of women are landowners in Ecuador. Moreover, sharecropping is an option for landless mothers to access land in exchange for sharing half of the crops [25]. Local foods encompassed pea flour, yellow carrots, radish, lupine seeds, fava beans, turnip, corn flour beverage, red onions, corn, zucchini leaves, lima bean flour, barley beverage, potatoes, and quinoa [28, 31]. Most of these foods are sold in the markets of urban areas, which highlights that quality foods do not remain in the rural communities of Ecuador.

Due to the focus and potential profits of urban markets, these traditional foods are not readily available in rural areas, and children often eat bread or snacks [32]. Family diets in rural areas in the Andean context are more often comprised of rice, potatoes and prepackaged processed foods instead of more nutritious foods, such as fruits and vegetables [31]. These easily accessible foods are most frequently consumed because of their affordability and due to the ability to be served in big quantities [27]. Quinoa, for example, is a traditional and nutritious food in the Ecuadorian highlands. However, families do not have access to quinoa as it is commonly exported, which furthers childhood malnutrition in the Ecuadorian context [29].

Along with less access to traditional quality foods, the use of plantations for growing non-traditional crops like flowers is prioritized and expanded for economic gain. Ecuadorian flower enterprises pushed the commercialization of non-traditional crops, exporting 50 million dollars of roses, carnations, and other flowers to the United States in 1994 [10]. However, agricultural exports have not necessarily improved the living conditions of women nor their children’s nutritional outcomes because wages remain low; therefore, mothers remained in poverty, lacking sufficient means to provide for their children. The use of plantations for growing non-traditional crops like flowers further reduces access to nutritious and readily available foods for consumption [29]. Changes in agricultural practices in rural areas of Ecuador impact the health and well-being of mothers and children.

4. DISCUSSION

Ecuador’s history of male dominant political and economic structures has contributed to the disenfranchisement of women and perpetuated poverty, particularly for single mothers and their children. In the late 19th century, various forms of subjugation were identified: agricultural exploitation from landowners to peasants and domestic violence. Women were marginalized not only at home but also in the larger society when they were neither identified as landowners nor involved in policy development. As such, their roles continued to be focused on domestic duties and childcare. In the early 20th century, social policies to enhance children’s well-being were instituted and subsequently failed because they were only driven by men. Nationalist gender norms maintained unequal rights and duties in Ecuador that weaken the economic and social spheres of the most vulnerable single mothers.

Women were absent from positions in the government which is a residual outcome of a long-standing patriarchal state hierarchy; a situation that is not easily changed. Gender equality in Ecuador was and still is underdeveloped due to single parenting, child labour, and migration. The political, economic and social structures hinder mother and child access to education, political power, maternal and child health services, entrepreneurial opportunities, adequate nutrition and opportunities for advancement. The results are measurable in terms of the health outcomes of women and children. Within these fissures, agricultural land reforms produced a significant gap for children’s nutritional, emotional and intellectual development in ways that perpetuate chronic malnutrition among children.

Food insecurity and poverty in rural areas are related to the commercialization of local products and the flower exports to North America. In fact, the shift in crops highlights how Ecuadorian flower enterprises sacrifice nutritional outcomes for large profits. Despite Ecuador moving from a low to middle-income country, single mothers and their children remained deprived of any benefits because they are paid low wages. Bolivia is an example of successful agricultural development that prioritizes the consumption of local foods as a key in reducing poverty, as well as the main method to alleviate hunger among rural communities [6]. Following this example, if food is readily available to children, it could tackle child poverty and improve mothers’ nutrition and the growth of their children. Empowering rural women in Ecuador through the reorganization of local food resources and access to loans will improve maternal-child health and hygiene. Additionally, investments in rural communities can provide opportunities for local entrepreneurships, which has gained the attention of other smaller communities that are willing to imitate these practices.

Despite calls for consciousness and change of mindsets, social disparities in Ecuador impede the successful empowerment of mother-child policy. Nationalist gender roles and other policies are historically characterized by corruption [29]. Corruption matters as it undermines the public expense for the privatization of wealth, normalizes inequities and diminishes the important roles of women in society. The higher the corruption, the more impoverished and less creative the society becomes to produce innovation that increases resources. Throughout the history of Ecuador and different government agendas, personal interests from privileged groups have distorted the productive capacities of those who are harder to reach, less valued by society, and working to their maximum abilities just to try and maintain a living. Political responsibility is required in Ecuador to advance women’s health, including children’s rights. To accomplish this, it is paramount to incorporate family education to break the cultural norm on how boys and men view girls and women, as well as prioritizing education on integrity, moral values, and the value of united families.

The size of the family and little opportunity to access health education in rural areas contribute to unique societal challenges to achieving a healthy family life. The path forward is to develop an approach to building trust by allocating health resources and infrastructure that prioritizes birth control, children’s growth monitoring, nutrition and sexual education, and food supplements for pregnant women. One key public health intervention is to build a healthy public policy that engages women in the community to ensure that what is expressed in their worlds of living in poverty far from urban areas is captured and considered [33]. In middle-income countries like Ecuador where resources are limited, health researchers and policymakers are called to create better governance structures by taking into account the local evidence of women’s realities. Their voices should be accounted for in the discourse about what the important health priorities are in their rural communities and how they should be addressed.

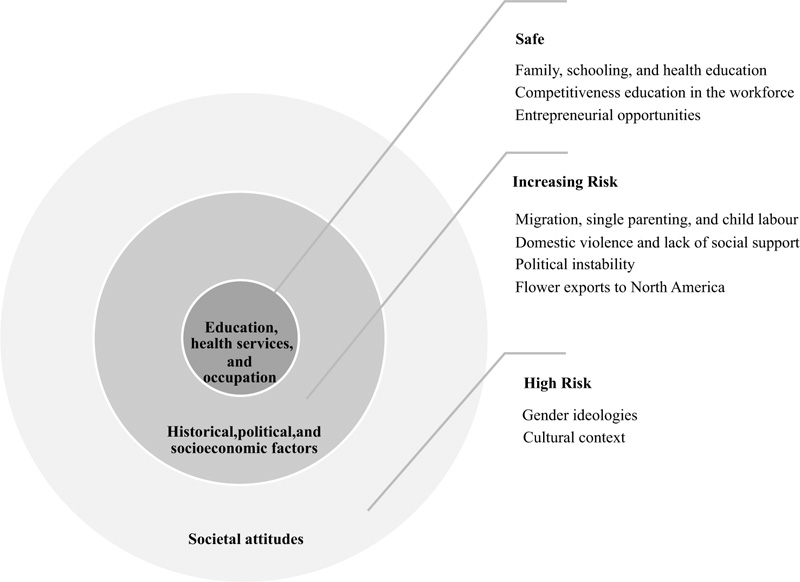

This narrative review has highlighted historical and social factors that have contributed to the disenfranchisement of women and the poor. Fig. (1) highlights the complexity inherent to single mothers and their children. The benefits of economic progress at a societal level do not necessarily reach the more marginalized members of the population. In fact, the very vehicles that improved Ecuador’s economic status have contributed to greater food insecurity, malnutrition and marginalization for single mothers and their children. The solutions must be grounded in greater political power for women, programs that target marginalized populations to improve their competitiveness in the workforce, income and food supplements to ensure adequate nutrition for women and their children across all aspects of society. Longer-term solutions must include the recognition of gender marginalization in Ecuadorian society, changes in societal attitudes and norms that foster greater responsibility for fathers in their role in caring for their children, and the need to be proactive about providing pathways to land ownership, entrepreneurship and advancement for women.

CONCLUSION

Single mothers in Highland Ecuador experience institutionalized gender bias, historical gender discrimination, and societal attitudes that lead to poor nutrition, limited education, and poverty resulting in poor health and quality of life for both women and children. Rurality and isolation present significant barriers to opportunities for political involvement and participation in the labour force. The contributors to gender poverty are complex and long-standing. Women’s empowerment is pivotal to address these challenges. This narrative review of the literature linked gender inequality to historical patterns of cultural gender norms in rural agricultural livelihoods that negatively impacted single mothers and children’s nutritional and health outcomes. Gender inequality in Ecuador is the main barrier that contributes to both food insecurity and poverty for a substantial proportion of the population. Future public policy in Ecuador should consider the status of women in society and their rural agricultural livelihoods and how gender roles and sociocultural factors can be barriers to improving the health and well-being of single mothers and children.

LIST OF ABBREVIATION

| USAID | = US Agency for International Development |

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable.

FUNDING

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.