SYSTEMATIC REVIEW

An Integrative Literature Review on Factors Affecting Breastfeeding in Public Spaces

Madimetja Nyaloko1, *, Welma Lubbe1, Karin Minnie1, 2

Article Information

Identifiers and Pagination:

Year: 2022Volume: 15

E-location ID: e187494452206274

Publisher ID: e187494452206274

DOI: 10.2174/18749445-v15-e2206274

Article History:

Received Date: 27/2/2022Revision Received Date: 31/3/2022

Acceptance Date: 22/4/2022

Electronic publication date: 22/08/2022

Collection year: 2022

open-access license: This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Public License (CC-BY 4.0), a copy of which is available at: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/legalcode. This license permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Background:

Breastfeeding in public spaces remains a challenge for mothers globally. This review aims to synthesise the available published evidence to understand factors that affect breastfeeding in public spaces globally.

Methods:

The current review was conducted using a systematic review methodology guided by Whittemore and Knafl's integrative literature review steps. The relevant studies were digitally searched on EBSCOhost, Google Scholar, and PubMed databases. The review included literature from 2013 to 2018 to ascertain the factors affecting breastfeeding in public spaces. The screening concerned three rounds, including studying topics, abstract scrutinising, and ultimately checking content. Included studies were critically appraised by two reviewers using the Critical Appraisal Skill Programme checklist. Data were pooled from included studies using a matrix. Finally, the data were synthesised and analysed to identify new themes relevant to the review topic.

Results:

There were 224 studies retrieved that discussed breastfeeding. However, only six research studies met the inclusion requirements and were subjected to the review procedure. The included studies were reviewed and integrated into four themes: lack of support, sexualisation of breasts, media, and culture.

Conclusion:

The findings indicated that mothers are unsupported to breastfeed in public spaces, posing a barrier to exclusive breastfeeding. Therefore, the main focus should be on educating community members regarding the advantages of breastfeeding to support, encourage, and promote breastfeeding whenever and wherever inclusive of public spaces.

1. INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND

Breastfeeding exclusively for the first six months of life significantly optimises the welfare of infants. Exclusive breastfeeding is a practice in which an infant receives only breast milk with no additional liquid or solids added except for the vitamins, minerals, or medicines [1]. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that infants be exclusively breastfed for at least six months [2].

Breastfeeding is advantageous to infants, mothers, and community members and is connected with positive health outcomes [3]. The breast milk components provide the infant with the required nutrients [4, 5]. Furthermore, the nutritional components of breast milk are more efficiently digested and absorbed than formula as it constitutes of living ingredients, hormones, and enzymes [6].

Breastfeeding is also a fundamental aspect of the reproductive process that directly impacts maternal health. Scientific evidence indicates that breastfeeding acts as a preventative measure against breast, ovarian, and endometrial cancers by suppressing the ovulation and ovulatory hormones associated with the development of these cancers in mothers [7, 8]. The evidence also indicates that optimal breastfeeding practice reduces the risk of developing postpartum depression [9].

Furthermore, through optimal breastfeeding practice, the government reduces spending on health care and hospitalisation by developing a healthy nation through breastfed infants who are less likely to become ill [10-12]. Breastfeeding conserves energy by reducing the manufacture, packaging, and distribution of breast milk alternatives [13]. Breastfeeding also has environmental benefits compared to breast milk substitutes, which consume resources and generate significant waste that clogs landfills [14].

Despite the benefits of breastfeeding and the WHO's recommendation, global breastfeeding rates remain low. According to the World Alliance for Breastfeeding Action [15] and UNICEF [16], only four in every ten infants aged less than six months are exclusively breastfed as per WHO's recommendations. The efforts are required to achieve Sustainable Development Goal [no. 3] to increase exclusive breastfeeding rates to the targeted 70% by 2030 [17].

Numerous studies have explored the variables contributing to low breastfeeding rates, including maternal age, education, knowledge, parity, and employment [18-21]. In addition, Perappadan [22] revealed that mothers also face difficulties breastfeeding in public areas. While previous research has been critical in advancing our understanding of the factors affecting breastfeeding, an integrated literature review on breastfeeding in public areas is lacking. Therefore, the current review will synthesise the extant literature on factors affecting breastfeeding in public spaces to formulate recommendations to alleviate the issues that breastfeeding mothers encounter in public spaces to scale up the breastfeeding rate to the recommended levels.

2. METHODS

An integrative literature review was systematically performed using a systematic review methodology guided by Whittemore and Knafl's [23] five steps (review question, search strategy, data evaluation/critical appraisal, data analysis, and presentation) to enhance transparency and minimise bias.

2.1. Review Question

The formulation of the review question in consultation with stakeholders serves as a point of departure for conducting an integrative literature review. The PICOTS framework components aided and steered the formulation of the research question. PICOTS is an acronym that stands for (P) Population of interest, (I) Issue of interest, (C) Comparison, (O) Outcomes of interest, (T) Time, and (S) Setting [24-26]. The reviewers applied PIOS variables from the PICOTS framework as follows:

- P-breastfeeding mothers

- I- breastfeeding in public spaces

- O-factors influencing breastfeeding in public spaces

- S-global

The current integrative literature review was guided by the following question: “What is the available published evidence on factors affecting mothers when breastfeeding in public spaces globally?”

2.2. Search Strategy

The search strategy began with a preliminary scoping search to avoid duplication of the review. The scoping search aided the development of keywords. Three reviewers developed and executed the comprehensive search strategy in conjunction with a librarian from North-West University. Furthermore, hand searching was conducted to ensure that diverse knowledge was incorporated, eliminating bias. Additionally, the reference list of all included articles was manually searched for additional potential studies. The reviewer explored three core databases (EBSCOhost, Google Scholar, and PubMed) within the realm of infant alimentation to spot primary breastfeeding studies and their related factors, particularly in public spaces. The searching process merged the following keywords: “breastfeeding OR nursing OR lactation” AND “factors affecting OR factors influencing OR factors impacting” AND “public space OR public area OR general space” to find relevant studies consistent with the review question. The PRISMA diagram substantiated the quality of reporting and the transparency of the study selection process, both of which contribute to the review's credibility [27].

Establishing inclusion and exclusion criteria ensures that the review is completed in a structured manner [28] and includes relevant documents from a significant body of literature discovered during the search [29]. The current review included studies if they were (a) published in English and all other languages if the abstract was in English, (b) posted from 2013 to 2018 to reflect a balance between incorporating as many studies as possible during this review and staying relevant to the current breastfeeding information, and (c) studies involving factors that affect breastfeeding in public spaces. Studies were excluded if (a) published before the year 2013, (b) abstracts were written in any language other than English, and (c) included special needs participants, such as disabled mothers.

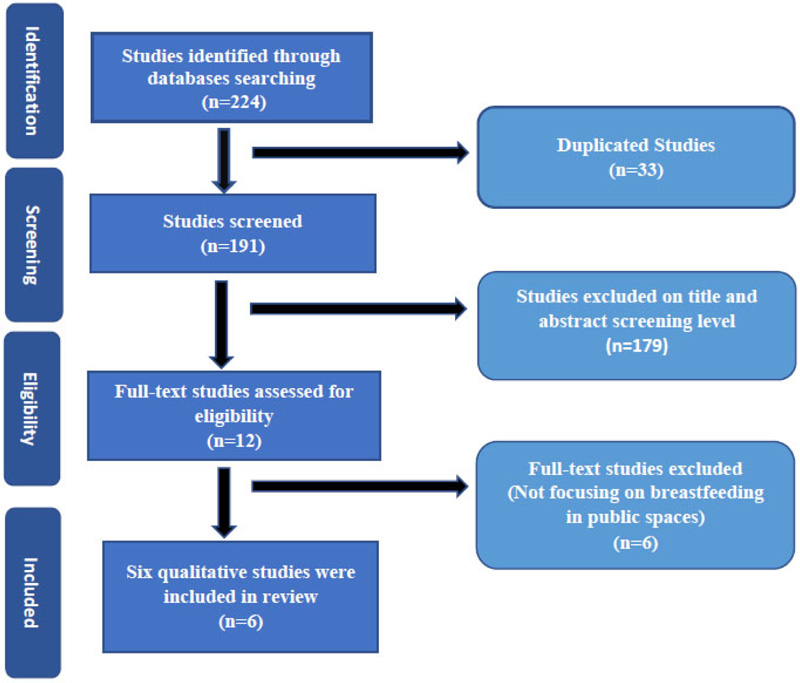

The screening process involved three stages: title selection and elimination of duplication, abstract analysis, and content analysis. The database search resulted in the identification of 224 studies. 33 duplicated studies were removed. Two reviewers screened 191 studies and included only 6 studies focused on breastfeeding in public spaces (Fig. 1).

2.3. Critical Appraisal

The methodological quality of the included studies was critically appraised by two independent reviewers using published Critical Appraisal Skill Programme tools [30]. The CASP tools were selected because of their capability to appraise a broad range of studies, including systematic reviews, randomised controlled trials, qualitative research, economic evaluation studies, cohort studies, case-control studies, and diagnostic test studies [30]. The CASP checklists covered three significant areas: validity, results, and clinical relevance, and provided an evidence of quality (Table 1). All six studies were assessed and graded as “good quality” and addressed the review question. No studies were excluded due to poor methodological quality. The appraisals of both reviewers were consistent.

|

Fig. (1). PRISMA flow diagram of included studies concerning factors affecting breastfeeding in public spaces (Moher et al. 2009:264). |

| Citation | CA Tool | Quality of Evidence | Level of Evidence |

| Bylaska-Davies, P., 2015, ‘Exploring the effect of mass media on perceptions of infant feeding,’ Health Care for Women International, 36, 1056-1017. | CASP qualitative checklist | Good | 9/10 |

| Cripe, E.T., 2017, ‘You can’t bring your cat to work. Challenges mothers face combining breastfeeding and working’, Qualitative Research Reports in Communication, 18(1), 36-44. | CASP qualitative checklist | Good | 8/10 |

| Giles, F., 2018, ‘Images of a woman breastfeeding in public: solitude and sociality in recent photographic portraiture,’ International Breastfeeding Journal, 13(52), 1-12. | CASP qualitative checklist | Acceptable | 6/10 |

| Grant, A., 2016, ‘I... don’t want to see you flashing your bits around: Exhibitionism, mothering and good motherhood in perceptions of public breastfeeding’, Geoforum, 71, 52-61. | CASP qualitative checklist | Good | 9/10 |

| Hohl, S., Thompson, B., Escareno, M. & Duggan M., 2016, ‘Cultural norms in conflict: Breastfeeding among Hispanic immigrants in rural Washington State,’ Maternal and Child Health Journal, 20, 1549-1557. | CASP qualitative checklist | Excellent | 10/10 |

| Nikaiin, B., Donnelly, T.T., Band N.N., Dorri R.A., Muhammad, A. & Patel, N., 2013, ‘Contextual factors influencing breastfeeding practices among Arab women in the State of Qatar,’ Qualitative Sociology Review, 7(3), 75-89. | CASP qualitative checklist | Good | 9/10 |

2.4. Data Extraction

Data were manually extracted from appraised six included studies using a standardised data extraction tool in an Excel tabular format to guarantee uniformity and definition of qualitative and quantitative summary [31, 32]. The Excel spreadsheet (Table 2) included authors, publication year, aim/purpose, design, sample size and characteristics, data collection, and instrument and findings [33]. The table allows the reader to judge the applicability of the findings (variances, similarities, and common themes) to the subject of breastfeeding in public spaces. The pooled data were synthesised and analysed to generate themes to address the review question.

Table 2. Characteristics of included studies-data extraction table.

| Author and Published Year | Aim/Purpose | Research Design | Sample Size (SZ) and Sample Characteristics (SC) | Data Collection and Instruments | Findings regarding factors that influence breastfeeding in public spaces. |

| 1. Bylaska-Davies, P., 2015. |

To explore the effect of mass media on perceptions and influence of a mother’s breastfeeding decision and other contributory factors associated with breastfeeding that could be incorporated in mass media images/messages. | Qualitative, descriptive design. | SZ- 32 respondents SC-pregnant and postpartum women |

Interview via text and visual Internet site | Respondents stated that media representations of infant feeding other than formula advertisement were scares, particularly breastfeeding representations. The cultural sexualization of breasts leads to a lack of support for breastfeeding in public spaces. Commercial interest in advertising and promoting formula feeding is a deterrent to breastfeeding. |

| 2. Cripe, E.T., 2017. |

To examine the challenges that mothers face combining breastfeeding and working. | Qualitative, exploratory design. | SZ-23 mothers. SC- two groups of mothers. Some worked at home, and others work outside their homes. |

Interview | Mothers reported a lack of support from employers and colleagues for breastfeeding purposes. |

| 3. Nikaiin, B. et al., 2013. | To find ways to effectively promote breastfeeding practices among Qatari women by investigating factors affecting how Qatari women decide to engage in breastfeeding practices and their overall breastfeeding knowledge. | Qualitative, exploratory design. | SZ- 32 respondents SC- Qatari women, natural and non-natural Arabic women |

Face to face interview | Knowledge of breastfeeding and professional support for learning breastfeeding techniques. Social support, including parental, spousal, cultural, and religious values regarding breastfeeding, encourages breastfeeding. |

| 4. Hohl, S. et al., 2016. | To examine breastfeeding perceptions, experiences, and attitudes | Qualitative, exploratory design. | SZ - 20 respondents SC – Parous Hispanic women of low acculturation aged 25-48 years residing in rural Washington State |

Face to face interview | Adapting to life in the US: Cultural norm in conflict. Hispanic culture promotes breastfeeding anywhere, including public spaces, while US citizens see it as ill behavior. |

| 5. Grant, A., 2016. | To understand the views of those who might observe public breastfeeding and to complement research on mothers’ breastfeeding experiences. | Qualitative descriptive |

884 comments from social media. | Online comments | Perceptions that mothers who were breastfeeding in public invite sexual contact with men. Mothers who are breastfeeding have no morals; they are stupid and practice deviant behavior Comments from media were anti-breastfeeding in public, labeling mother’s as undesirable |

| 6. Giles, F., 2018. | To provide a textual analysis of contemporary photographic portraiture to interpret the meaning of the keywords and their pattern of significance. | Qualitative, descriptive design | Various online media pictures | Online pictures | The media, in general, has continued to shy away from images of breastfeeding mothers. |

2.5. Data synthesis and Analysis

Data synthesis is a textual technique for assembling ideas and findings from various sources to reveal the whole body of knowledge [34]. The reviewers combined the data into a coherent whole and subjected it to thematic analysis to generate themes that addressed the review question. The reviewer used a matrix to classify and categorise the different arguments presented on an issue [35]. Furthermore, the matrix enabled the exploration of potential patterns of various findings between different studies.

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The four main factors affecting breastfeeding in public spaces were lack of support, culture, media, and sexualisation of breasts.

3.1. Lack of Support

Several studies have found that a lack of support negatively impacts breastfeeding in public spaces. Numerous authors [36-39] concurred that mothers opt to formula feed as a desire to escape offensive remarks, bad judgments, and glares towards them when breastfeeding in public places. Furthermore, Nikaiin et al. [40] supplemented that a lack of support also discourages and demotivates mothers from breastfeeding in public spaces and at home or in their private areas.

This finding supported the previous studies done in Canada [41, 42] and Ireland [43]. The similarities of these findings could be that no solid strategies and policies have been implemented to encourage and educate communities on the value of supporting breastfeeding in general, including in public spaces. Public health education programmes and outreach can serve as an information disseminating tool to encourage support for breastfeeding mothers.

3.2. Culture

Studies have demonstrated that culture has both detrimental and positive effects on breastfeeding in public areas. For instance, Nikaiin et al. [40] indicated that cultures, such as Muslims, consider breastfeeding a spiritual matter; therefore, they advocate and permit mothers to breastfeed anytime, including in public spaces. Demonstrating how cultural norms and values can impede breastfeeding in public spaces, Hohl et al. [37] described how U.S. communities display signs of disapproval, such as grimy looks and negative comments, towards mothers breastfeeding in public spaces.

Literature has also highlighted a similar trend where various cultures in countries, such as Mongolia [44] and Saudi Arabia [45], endorse breastfeeding in public spaces while others, such as Hong Kong [46], the U.K [47], Kenya [48], consider public breastfeeding as taboo and unacceptable. Cultural norms regarding breastfeeding in public spaces vary considerably between communities. The variation could be due to the fact that culture is context-bound. As a result, individual mothers should practice their customs and human rights when breastfeeding in public spaces.

3.3. Media

Media, identified in three articles, is one of the quickest and most efficient routes to disseminate information. Despite its ability to disseminate information quickly and extensively, the media is less concerned about breastfeeding. Several studies [38, 39, 49] report that media excludes breastfeeding content. For instance, Giles [49] noted that an Australian magazine was exclusively made available to those who paid for the subscription with images of the celebrity breastfeeding; however, the identical version was made available to the public without photographs of celebrity breastfeeding but instead depicted her and the child asleep. Therefore, the media is denying the general population the opportunity to view breastfeeding as an issue of public interest rather than a healthcare institution-based subject.

Consistently with the findings of the current review, a previous study noted that the media encompasses a tendency not to market breastfeeding to the general public [50]. Although Steward-Knox et al. [51] disagreed, the authors concurred that the media portrays breastfeeding as a non-public activity, discouraging breastfeeding in public spaces. To eradicate this barrier, the government should have a directive for the media to advertise breastfeeding (community outreach) as an amiable and convenient feeding method for indoor and outdoor settings.

3.4. Sexualisation of Breast

Studies [37, 39] have discussed the sexualisation of breasts as impacting breastfeeding in public spaces. People's perceptions regarding the breast differ according to cultural socialisation in varying constituencies. One study [37] reported that mothers who grow up exposed to breastfeeding perceive breasts as lactating organs, therefore breastfeeding in public for them is not an issue. On the contrary, another study [39] noted that mothers who perceive the breast as a sexual organ are reluctant to breastfeed in public spaces and exhibit negative sentiments toward those breastfeeding in public spaces.

The current review findings correlate with studies done in the U.K [52] and Ireland [43]. The rationale behind this could be that communities in these countries are socialised to relate breasts mainly with sexual connotations and activities instead of feeding/mammary gland. Therefore, there is a need for a socialisation paradigm shift to detach preconceived ideas of associating breasts with intimate activities.

4. LIMITATIONS

Limited information has been documented concerning factors affecting breastfeeding in public spaces locally (in South Africa) and globally. Although the review aimed to explore literature regarding factors affecting breastfeeding in public spaces, its sample size was small. A larger sample of studies might have revealed diverse viewpoints regarding breastfeeding in public spaces.

CONCLUSION

In various countries, community members do not accept breastfeeding in public spaces. The most reported factors that negatively affect and discourage breastfeeding in public spaces are lack of support from the general population, cultural norms and values, media fraternity, and sexualisation of breasts. According to a South African study, the better people are informed regarding the breastfeeding benefits, the higher they demonstrate supportive actions toward breastfeeding mothers in public spaces [53]. The authors advise that supportive actions towards breastfeeding mothers in public spaces, both outdoors and indoors, should be implemented along with the development of public education to deliver breastfeeding teaching in collaboration with private sectors, with exclusive breastfeeding rates targeted at 70% by 2030 [17].

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| CASP | = Critical Appraisal Skills Programme |

| HREC | = Health Research Ethics Committee |

| PRISMA | = Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| UK | = United Kingdom |

| USA | = United States of America |

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable.

STANDARDS OF REPORTING

Prisma guidelines were followed.

FUNDING

The review was partly aided financially by the North-West University, South Africa.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that no conflict of interest influenced this review regarding financial or relationship concerns.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank the NWU librarians for their expert guidance and assistance in identifying and obtaining the relevant literature sources.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

The supplementary material used during the current review are available from the corresponding author [M.N.] on request.

DISCLAIMER

The views displayed in this review are expressions of the authors' personal views and not those of any official institution or funder.

REFERENCES

| [1] | Elyas L, Mekasha A, Admasie A, Assefa E. Exclusive breastfeeding practice and associated factors among mothers attending private pediatric and child clinics, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. Int J Pediatr 2017; 2017(8546192): 1-9. |

| [2] | Infant and young child feeding: model chapter for textbooks for medical students and allied health professionals 2019. |

| [3] | Okafor IP, Olatona FA, Olufemi OA. Breastfeeding practices of mothers of young children in Lagos, Nigeria. Niger J Paediatr 2013; 41(1): 43-7. |

| [4] | Du Plessis D. Pocket guide to breastfeeding 2005. |

| [5] | Bührer C, Genzel-Boroviczény O, Jochum F, et al. Ernährung gesunder Säuglinge. Monatsschr Kinderheilkd 2014; 162(6): 527-38. |

| [6] | Mitch B, Sarah SB, Tony W. Child public health 2006. |

| [7] | Penny T, Kate B, Harriet E. Childcare and education 2nd ed. 2005. |

| [8] | Davis SK, Stichler JF, Poeltler DM. Increasing exclusive breastfeeding rates in the well-baby population: an evidence-based change project. Nurs Womens Health 2012; 16(6): 460-70. |

| [9] | Stuebe AM, Grewen K, Meltzer-Brody S. Association between maternal mood and oxytocin response to breastfeeding. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2013; 22(4): 352-61. |

| [10] | Kerac M, Blencowe H, Grijalva-Eternod C, et al. Prevalence of wasting among under 6-month-old infants in developing countries and implications of new case definitions using WHO growth standards: a secondary data analysis. Arch Dis Child 2011; 96(11): 1008-13. |

| [11] | Nutriinfo. Benefits of breastfeeding to child, mother, family, and community-World Breastfeeding Week 2016.http://nutriinfong. blogspot.co.za/2016/08/benefits-of- breastfeeding-to-child.html?m=1 |

| [12] | Virtue. The nation benefits from breastfeeding 2017.http://virtua.org/article/the- |

| [13] | GIFA. Green Feeding – climate action from birth https:// www.gifa.org/wp- content/uploads/2019/11/2019-Green-Feeding-Europe-Worldwide-Nov6.pdf2020. |

| [14] | Joffe N, Webster F, Shenker N. Support for breastfeeding is an environmental imperative. BMJ 2019; 367: l5646. |

| [15] | World Alliance for Breastfeeding Action. World Breastfeeding Week action folder 2012.http://worldbreastfeedingweek.org/downloads.shtml |

| [16] | UNICEF. WHO The extension of the 2025 maternal, infant, and young World Alliance for Breastfeeding Action World Breastfeeding Week action folder 2012.http://worldbreastfeedingweek.org/downloads. shtml |

| [17] | UNICEF. The state of food security and nutrition in the world 2019.http://www.fao.org/3/ca5162en/ca5162en.pdf |

| [18] | Seifu W, Assefa G, Egata G. Prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding and its predictors among infants aged six months in Jimma town, Southwest Ethiopia, 2013. J Pediatr Neonatal Care 2014; 1(3): 00017. |

| [19] | Lok KYW, Bai DL, Tarrant M. Predictors of breastfeeding initiation in Hong Kong and Mainland China born mothers. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2015; 15(1): 286. |

| [20] | Angadi M, Jawaregowda S. Gender discrimination in relation to breast feeding practices in rural areas of Bijapur district, Karnataka. Int J Contemp Pediatrics 2015; 2(4): 340-4. |

| [21] | Reddy S, Abuka T. Determinants of exclusive breastfeeding practice among mothers of children under two years old in Dilla Zuria District, Gedeo Zone, Snnpr, Ethiopia, 2014. J Pregnancy Child Health 2016; 3: 224. [https://doi:10.4172/2376- 127X.1000224]. |

| [22] | Perappadan BS. Delhi –Breastfeeding a challenge for over 70% of mothers 2018. https://www.thehindu.com/news/cities/Delhi/breastfeeding-a-challenge-for-over-70- of-mothers/article24618478.ece |

| [23] | Whittemore R, Knafl K. The integrative review: Updated methodology. J Adv Nurs 2005; 52(5): 546-53. |

| [24] | Khan KS, Kunz R, Kleijnen J, Antes G. Five steps to conducting a systematic review. J R Soc Med 2003; 96(3): 118-21. |

| [25] | Melnyk BM, Fineout-Overholt E. Evidence-based practice in nursing and healthcare: A guide to best practice 2014. |

| [26] | Cavalcanti Lira RP, Rocha EM. PICOT: Imprescriptible items in a clinical research question |

| [27] | Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med 2009; 151(4): 264-269, W64. |

| [28] | Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, et al. PRISMA-P Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev 2015; 4(1): 1. |

| [29] | Lubbe W, Ham-Baloyi W, Smit K. The integrative literature review as a research method: A demonstration review of research on neurodevelopmental supportive care in preterm infants. J Neonatal Nurs 2020; 26(6): 308-15. [doi:10.1016/j.jnn.2020.04.006]. |

| [30] | Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP quantitative checklist 2018.uk.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/CASP-Qualitative-Checklist-2018.pdf |

| [31] | Colquhoun HL, Levac D, O’Brien KK, et al. Scoping reviews: Time for clarity in definition, methods, and reporting. J Clin Epidemiol 2014; 67(12): 1291-4. |

| [32] | Munn Z, Moola S, Riitano D, Lisy K. The development of a critical appraisal tool for use in systematic reviews addressing questions of prevalence. Int J Health Policy Manag 2014; 3(3): 123-8. |

| [33] | Garrard J. Health sciences literature review made easy: the matrix method 2017. |

| [34] | McCombes S. How to synthesize written information from multiple sources: Simply Psychology 2020.www.simplypsychology.org/synthesising.html |

| [35] | Nowell LS, Norris JM, White DE, Moules NJ. Thematic Analysis. Int J Qual Methods 2017; 16(1): 1-13. |

| [36] | Cripe ET. You can’t bring your cat to work: Challenges mothers face combining breastfeeding and working. Qual Res Reports Commun 2017; 18(1): 36-44. |

| [37] | Hohl S, Thompson B, Escareño M, Duggan C. Cultural norms in conflict: Breastfeeding among Hispanic immigrants in rural Washington State. Matern Child Health J 2016; 20(7): 1549-57. |

| [38] | Grant A. “I…don’t want to see you flashing your bits around”: Exhibitionism, othering and good motherhood in perceptions of public breastfeeding. Geoforum 2016; 71: 52-61. |

| [39] | Bylaska-Davies P. Exploring the effect of mass media on perceptions of infant feeding. Health Care Women Int 2015; 36(9): 1056-70. |

| [40] | Nikaiin BB, Nazir N, Mohammad A, Donnelly T, Dorri RA, Petal N. Contextual factors influencing Breastfeeding Practices among Arabs women in the State of Qatar. Qualitative Sociology Review 2013; 9(3): 74-95. |

| [41] | Sheeshka J, Potter B, Norrie E, Valaitis R, Adams G, Kuczynski L. Women’s experiences breastfeeding in public places. J Hum Lact 2001; 17(1): 31-8. |

| [42] | Rempel LA, Rempel JK. The breastfeeding team: The role of involved fathers in the breastfeeding family. J Hum Lact 2011; 27(2): 115-21. |

| [43] | Sittlington J, Stewart-Knox B, Wright M, Bradbury I, Scott JA. Infant-feeding attitudes of expectant mothers in Northern Ireland. Health Educ Res 2006; 22(4): 561-70. |

| [44] | Kamnitzer R. In Culture Parents: Breastfeeding in the Land of Genghis Khan 2011. https://www.incultureparents.com/2011/02/breastfeeding-Land-Genghis-Khan/ |

| [45] | Riordan J. The cultural context of breastfeeding 2005; 718-9. |

| [46] | Ward LM, Merriwether A, Caruthers A. Breasts are for men: media, masculinity ideologies and men’s beliefs about women’s bodies. Sex Roles 2006; 55: 703-14. |

| [47] | Kong SKF, Leed F. Breastfeeding practices. Breastfeeding J Adv Nurs 2004; 46(4): 369-79. |

| [48] | Kimani-Murage EW, Wekesah F, Wanjohi M, et al. Factors affecting actualisation of the WHO breastfeeding recommendations in urban poor settings in K enya. Matern Child Nutr 2015; 11(3): 314-32. |

| [49] | Giles F. Images of women breastfeeding in public: Solitude and sociality in recent photographic portraiture. Int Breastfeed J 2018; 13(1): 52. |

| [50] | Henderson L, Kitzinger J, Green J. Representing infant feeding: Content analysis of British media portrayals of bottle feeding and breast feeding. BMJ 2000; 321(7270): 1196-8. |

| [51] | Stewart-Knox B, Gardiner K, Wright M. What is the problem with breast-feeding? A qualitative analysis of infant feeding perceptions. J Hum Nutr Diet 2003; 16(4): 265-73. |

| [52] | Wall G. Moral constructions of motherhood in breastfeeding discourse. Gend Soc 2001; 15(4): 592-610. |

| [53] | Nyaloko M, Lubbe W, Minnie K. Perceptions of mothers and community members regarding breastfeeding in public spaces in Alexandra, Gauteng Province, South Africa. Open Public Health J 2020; 13(1): 582-94. |