All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

The Comparison of Physical Activity, Cognitive Function, and Depression between Older and Middle-Aged Adults

Abstract

Background:

Aging increased the risks of cognitive impairment and depression. Then, these conditions can lead to poor quality of life by reducing one’s ability to perform activities of daily living. Recently, it is established that physical activity can decrease the cognitive decline and the risk of depression in older adults. Moreover, regular physical activity can improve physical and mental functions in populations of all ages. However, level and speed of cognitive decline occurs varies greatly among individual especially the difference between middle-aged and older adults.

Objective:

This study aimed to focus on the comparison of physical activity, cognitive function and depression between older and middle-aged adults, which has never been done before. Moreover, the associations of physical activity with cognitive impairment and depression were also investigated in older and middle-aged adults. The information in this study will provide an understanding regarding the design of physical activity program for different age groups.

Methods:

All participants were divided into two groups of 50 middle-aged adults and 50 older adults. The assessments of physical activity, cognitive function, and level of depression were conducted for all participants.

Results:

The total level of physical activity and cognitive function in older adults was decreased when compared with middle-aged ones. Moreover, each work and transportation domain of physical activity in older adults also was decreased when compared with that in middle-aged ones. However, the leisure domain of physical activity in older adults was increased via a decreasing depression level. In addition, the level of physical activity associated with both cognitive function and depression and depression alone in middle-aged and older adults, respectively.

Conclusion:

We suggested that total level of physical activity in older adults can increase via stimulating work and transportation activities in physical activity program. Moreover, the level of physical activity associated with both cognitive function and depression and depression alone in middle-aged and older adults, respectively.

1. INTRODUCTION

The number of older people has increased worldwide [1]. There were almost one billion people aged 65 or older globally during 2020 [2]. That figure is expected to increase nearly double towards 2 billion by 2050 [1, 2]. Previous studies showed that aging increased the risk of several health problems, such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, dementia, obesity, and mental health issues [3-6]. These conditions can lead to poor quality of life (QOL) by reducing the ability to perform activities of daily living (ADLs) [3-6]. It has been established recently that aging also increases the risk of cognitive impairment, dementia [7-9] and depression [10-12]. Thus, researchers try to prevent health problems in older adults by decreasing cognitive impairment and mental health problems and maintaining QOL by increasing the ability to perform ADLs. Recent studies showed that one potential strategy for preventing and decreasing cognitive decline and mental health problems was physical activity [13-15], which is known to involve movements of the body that require energy expenditure [16]. The physical activity is categorized into three types: occupational, household and leisure [16]. The studies demonstrated that high levels of physical activity were associated with low incidence of dementia and mild cognitive impairment (MCI) [14, 17, 18]. Furthermore, it has been established that physical activity can also reduce the prevalence of depression [19-21]. Moreover, it was established that regular physical activity can improve physical and mental functions in populations of all ages [22-27]. However, it is known that the level and speed of cognitive decline vary greatly among individuals especially the difference of cognition between middle-aged and older adults [28, 29]. After that, the declining cognitive function with age can lead to the difference of ADLs performance between middle-aged and older adults. Therefore, this study aimed to focus on the comparison of physical activity, cognitive function and depression between older and middle-aged adults, which has never been done before. Moreover, the associations of physical activity with respect to cognitive impairment and depression were also investigated in older and middle-aged adults. This study's findings will help with the design of intervention programs for various age groups that promote physical exercise, cognitive development, and mental health.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.1.1. Study Design

We conducted the study on older and middle-aged adults living in the community. A cross-sectional study design was employed to explore the differences between physical activity, cognitive function, and depression in older and middle-aged adults. In addition, the associations of physical activity with cognitive impairment and depression between older and middle-aged adults were explored.

2.1.2. Setting

The older and middle-aged people living in the Nongpakhrang community in Chiang Mai province, Thailand, were invited to participate in the study via an electronic survey. After that, all of the participants gave written informed consent.

All the methods were performed as per the relevant guidelines and regulations. All data were collected through face-to-face interviews between the participant and the researcher.

2.1.3. Participants

The population of this study comprised Nongpakhrang community members in Chiang Mai province, Thailand. Moreover, we also studied the participant who had regular physical activity. It is established that the person's lifestyle is one of the essential factors in determining the level of physical activity and a predictor of long-term response to physical activity [30].

Thus, the inclusion criteria of this study were active adults who had participated in regular activities at least three times a week for at least six consecutive months. In this study, active adults who had participated in regular activities in the past six months from the center of activities and health services in the Nongpakhrang community in Chiang Mai province, Thailand, were randomly selected. After that, all participants were divided equally into two groups of 50 middle-aged (ages 36–59 years) and 50 older adults (aged 60 years or above). The assessments of physical activity, cognitive function, and level of depression were conducted for all participants on the same day. The eligibility criteria used in this study included lack of physical disability and ability to sit for 60 minutes for each study protocol.

2.2. The Assessment of Physical Activity

In this study, the Global Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPAQ), initially designed by the World Health Organization (WHO), was used to assess physical activity [31, 32]. The total physical activity score was classified into two groups, reflecting on whether or not they engage in weekly physical activity (sufficiently active or inactive) [33]. Participants achieving a minimum of at least 600 MET-minute per week were categorized as sufficiently active, while those with total physical activities scores of less than 600 MET-minute per week were categorized as inactive [32].

2.3. The Cognitive Function Assessment

In this study, the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) was used to assess mild cognitive impairments (MCI) [34]. MoCA includes seven items: executive functions, visuospatial abilities, language, attention, working memory, abstraction and orientation. MoCA test-retest reliability was 0.92 (P < .001) and internal consistency was 0.8334. The total score was 30 points, with a score of 25 or above considered normal.

2.4. The Assessment of Depression Level

In this study, depression was assessed using the Thai version of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) [35], which has good psychometric properties for screening for major depression [35]. The level of depression was classified into five levels depending on the total PHQ-9 score; normal level (0 to 4 points), mild depression (5 to 9 points), moderate level (10 to 14 points), moderately severe depression (15 to 19 points), and severe depression (20 to 27 points) [35]. The PHQ-9 was administered in this study by an occupational therapist, the time taken to administer the assessment ranged from 10 to 15 minutes.

2.5. Data Analysis

All data were presented as mean values ± SEM. The t-test was used to compare the difference in physical activity, depression, and MoCA scores between middle-aged and older adults. The Pearson χ2 test was used to analyze categorical variables. This study also studied categorical variables regarding health status, including the history of head injury and underlying disease. It is established that a history of head injury was associated with cognitive impairment [36]. Also, underlying diseases, including hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes, were associated with cognitive impairment [37, 38]. Thus, categorical variables regarding health status, including the history of head injury and underlying disease, were also studied in this study. The multicollinearity index was used to analyze the correlation between physical activity and associated factors. A P value < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

3. RESULTS

3.1. General Characteristics of the Middle-aged and Older Adults

General characteristics of middle-aged and older adults are shown in Table 1. The results showed that all parameters had no significant difference when comparing the two groups (the middle-aged and older adults).

3.2. The Physical Activity of the Middle-aged and Older Adults

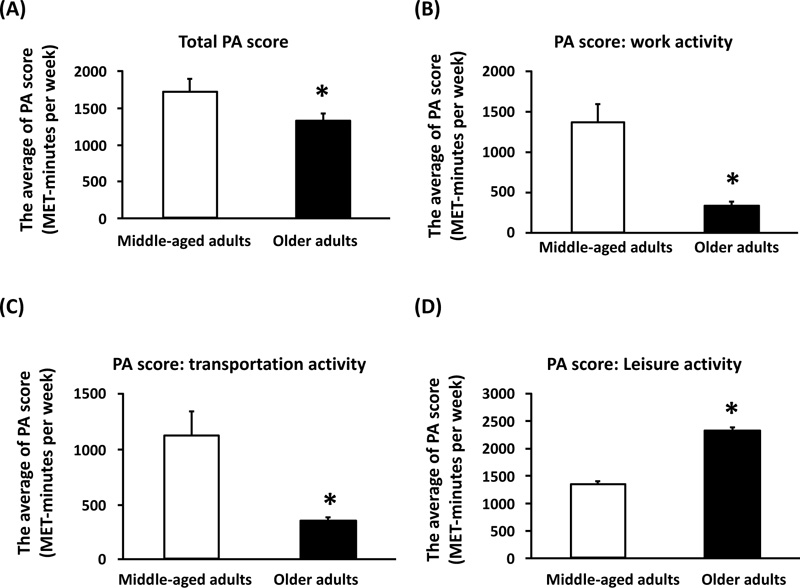

The ability of middle-aged and older adults to perform physical activity is shown in Fig. (1). In this study, the total physical activity (PA) score is shown in Fig. (1A). The results of this study showed that the average score for total physical activity was significantly lower in the older adults than in the middle-aged ones (Fig. 1A). It was established that the types of physical activity were divided into three activities, including work, transportation and leisure [31, 32]. The results demonstrated that the average scores for work and transportation activities were significantly lower for older adults than for middle-aged ones (Fig. 1B-C). However, it was found that the average scores for leisure activity were significantly higher for older adults than for middle-aged ones (Fig. 1D).

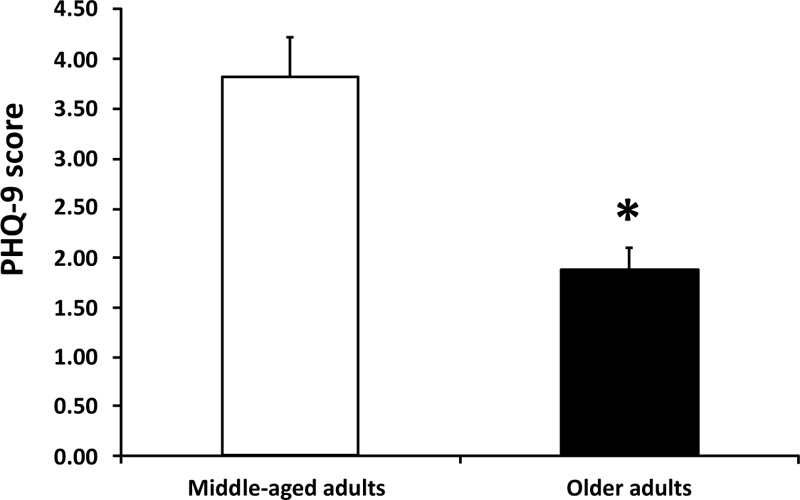

3.3. The Level of Depression in the Middle-aged and Older Adults

The level of depression in middle-aged and older adults is shown in Fig. (2). In this study, the depression score was determined using the PHQ-9. An increase in the PHQ-9 score is correlated with an increased severity of the depression level. The result of this study showed that the PHQ-9 score was significantly lower in older adults than in middle-aged ones. This result suggested that the level of depression was significantly reduced in the older adults when compared with the middle-aged ones (Fig. 2).

| General Characteristics | Middle-aged Adults |

| Gender (%) | - |

| Male | 28% |

| Female | 72% |

| Age (years) | - |

| Average (SE) | 48.64 ± 0.76 |

| Weight (kg) | - |

| (Average) | 62.26 ± 1.80 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | - |

| (Average) | 24.58 ± 0.64 |

| Education (%) | - |

| Uneducated | 0% |

| Educated | 100% |

| History of head injuries (%) | - |

| Yes | 0% |

| No | 100% |

| Underlying disease (%) | - |

| Yes | 16% |

| No | 84% |

* p < 0.05 vs. middle-aged adults.

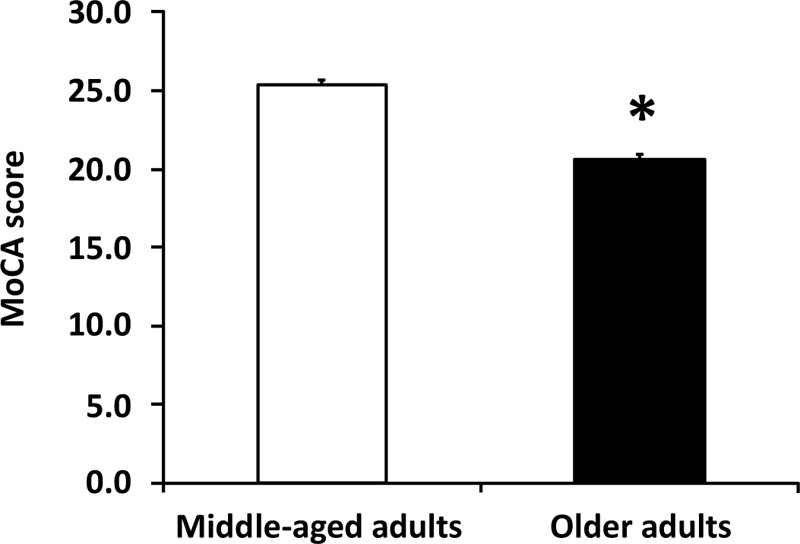

3.4. The Cognitive Function in the Middle-aged and Older Adults

Cognitive function levels are shown in Fig. (3). In this study, a decrease in MoCA score correlates with a decline in cognitive function. This study's results demonstrated that older adults' cognitive function was significantly lower than that of middle-aged ones (Fig. 3).

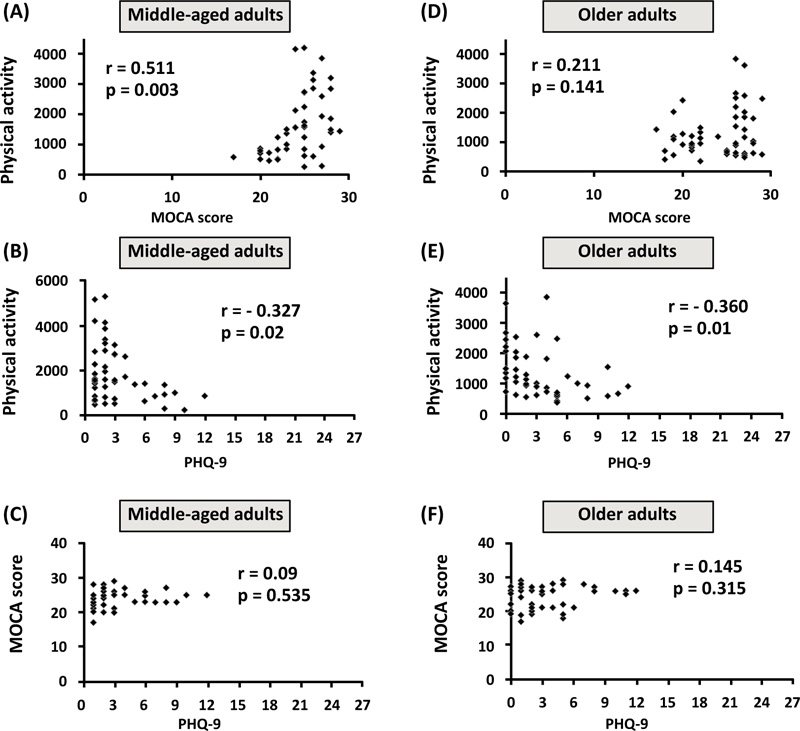

3.5. The Factors Associated with Physical Activity in the Middle-aged and Older Adults

Factors associated with physical activity in middle-aged and older adults are shown in Fig. (4). In middle-aged adults, the results showed that the MoCA score was associated positively with physical activity (r = 0.511, p = 0.003) (Fig. 4A). Moreover, the PHQ-9 score was associated negatively with physical activity in middle-aged adults (r = -0.327, p = 0.02 (Fig. 4B). However, it was found that the MoCA score showed no correlation with the PHQ-9 score in middle-aged adults (r = 0.09, p = 0.535) (Fig. 4C).

In the results, older adults showed that the PHQ-9 score was associated negatively with physical activity (r = -0.36, p = 0.01) (Fig. 4E). However, it was found that the MoCA score showed no correlation with physical activity in middle-aged adults (r = 0.211, p = 0.141) (Fig. 4D). Also, the MoCA score showed no correlation with the PHQ-9 score in older adults (r = 0.145, p = 0.315) (Fig. 4F).

4. DISCUSSION

The significant findings of this study are as follows:

(1) The total level of physical activity decreased in older adults compared with that in middle-aged ones.

(2) The level of physical activity in work and transportation domains decreased in older adults compared with that in middle-aged ones, while the leisure domain of physical activity in older adults was significantly higher than that of middle-aged ones.

(3) The level of depression in older adults significantly reduced compared with that of middle-aged ones.

(4) The cognitive function of older adults was significantly lower than that of middle-aged ones.

(5) The level of physical activity was associated with cognitive function and depression and only depression in middle-aged and older adults, respectively.

It was established that regular physical activity could improve physical and mental functions in populations of all ages [22-27]. The beneficial effects of physical activity were induced via decreasing body mass index, increasing cardiorespiratory and metabolic function, and reducing cognitive impairment [22, 27, 39]. This study found that the total level of physical activity decreased in older adults compared with middle-aged ones, which is consistent with a previous study that showed a decline in physical activity in older adults [40]. Moreover, the physical activity levels in transportation and work activities also were significantly lower in older adults than in middle-aged ones. It is possible that the age-associated changes in physical activity were caused by intensity and amount of physical activity and the incidence of obesity [40, 41]. However, it was found that active leisure activity, a type of physical activity, was significantly higher in older adults than in middle-aged ones. The psychological factor may cause an increase in the leisure activity in older adults. This hypothesis is consistent with previous studies showing that participating in leisure activities can decrease depression in older adults [42-44]. Furthermore, the depression result showed a significantly reduced level in the older adults compared with that in the middle-aged ones. Thus, this study suggested that increased active leisure activity in older adults was induced by an increased risk of mental health problems. In addition to total physical activity, the results of this study demonstrated that the cognitive function of older adults was significantly lower than that of middle-aged ones. This was consistent with a previous study that showed an increased cognitive decline in older adults [45]. In addition, a decrease in total physical activity in older adults may cause a decrease in cognitive impairment. Thus, this study found that cognitive function and total physical activity were lower in older adults than in middle-aged ones.

In this study, factors associated with physical activity in middle-aged adults were measured, and the results demonstrated that cognitive function was associated positively with physical activity. This finding is consistent with a study that showed that physical activity is associated with cognitive function in middle-aged adults [46].

Moreover, the results of this study first show that depression level was associated negatively with physical activity in middle-aged adults. In addition, factors associated with physical activity in older adults were measured, and the results showed that depression level was associated negatively with physical activity. This finding is consistent with studies that showed that adequate exercise was associated with depression in older adults [23, 47].

Thus, we suggested that the level of physical activity is associated with both cognitive function and depression and depression alone in middle-aged and older adults respectively. In the future, the mechanisms of factors associated with physical activity in middle-aged and older adults need to be investigated.

However, the level of physical activity may be associated with cognitive function and depression via activating Sirtuin 1. Recently, it has been established that Sirtuins (SIRTs) are seven nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+)-dependent protein deacetylases enzymes (SIRT1–7) that play an essential role in regulating cellular homeostasis [48]. In mammals, Sirtuins play key role during cell response, such as cell metabolism, cell cycle, apoptosis, and neuroprotection [49, 50]. The studies demonstrated that physical activity regulated glucose homeostasis and increased the autophagic process via activating Sirtuin 1 [48, 51, 52]. Thus, we suggested that Sirtuin 1 was activated through the induction of physical activity. The studies also showed that calorie restriction increased the autophagic process via activating Sirtuin 1 [53]. Autophagy is known as a cytoprotective process in mammalian tissues [53]. Inhibiting autophagy induced degenerative changes and increased pathological ageing in mammalian tissues [53]. The study showed that calorie restriction improved physical performance via increasing exercise energy efficiency and autophagic process [54]. It is consistent with a study that reported that both physical activity and calorie restriction could increase the autophagic process through activating Sirtuin 1 and lead to the attenuation of age-related disease [55].

Interestingly, the studies demonstrated that activation of Sirtuin 1 could attenuate cognitive impairment and depression [56-59]. Moreover, the study showed that Sirtuin 1 could be a critical biomarker of major depressive disorder [57]. Thus, the level of physical activity may be associated with both cognitive function and depression via activating Sirtuin 1. In the future, this hypothesis needs to be investigated.

For clinical application of this study, we suggested that the total level of physical activity in older adults can be increased via introducing work and transportation activities in physical activity programs. It is consistent with our results showing that the total physical activity level in older adults decreased compared with middle-aged ones. Moreover, each work and transportation domain of physical activity in older adults also decreased compared with that in middle-aged ones. Additionally, we suggested that the increase in physical activity level in middle-aged adults was associated with a decrease in cognitive impairment and depression. In contrast, an increase in physical activity level in older adults was associated with decreased depression. The information in this study can provide an understanding of factors associated with the change of physical activity levels in middle-aged and older adults, as well as an understanding regarding the design of physical activity programs for different age groups. For the limitations of this study, first, this study is a descriptive analysis, not analytical.

Second, we suggested that it is possible that the increase in active leisure activity in older adults was induced by decreasing the risk of mental health problem. However, this hypothesis has not been evaluated in this study. In the future, this hypothesis needs to be investigated. Thus, the covariables and confounders, which influence the level of physical activity, need to be studied in the future.

CONCLUSION

The significant findings of this study were that the total level of physical activity and cognitive function in older adults decreased when compared with middle-aged ones. Moreover, each work and transportation domain of physical activity in older adults also decreased compared with that in middle-aged ones. However, the leisure domain of physical activity in older adults increased. It is possible that the increase in active leisure activity in older adults was induced by decreasing the risk of mental health problem. In addition, physical activity is associated with cognitive function and depression and depression alone in middle-aged and older adults, respectively.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| QOL | = Quality of Life |

| MCI | = Mild Cognitive Impairment |

| MoCA | = Montreal Cognitive Assessment |

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Associated Medical Sciences, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai, Thailand (Ethic number: AMSEC-62EX-065).

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

The study on humans was conducted following the ethical standards of the Helsinki Declaration and Good Clinical Practice. No animals were used in this study. All methods were performed following the relevant guidelines and regulations.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

All participants gave written informed consent for participation in this study.

STANDARDS OF REPORTING

STROBE guidelines and methodologies were followed in this study.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

The data supporting the findings of the article are available within the article.

FUNDING

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by the Faculty of Associated Medical Sciences, Chiang Mai University, Thailand. Moreover, we would like to thank all staff and members of the Nongpakhrang Subdistrict Municipality in Chiang Mai province, Thailand, for their assistance throughout this study.