All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Experiences of Primary Health Care Clients in Jordan: Qualitative Study

Abstract

Objective:

This paper aims to understand the experiences of clients in utilising primary health care services in Jordan.

Design:

A qualitative study.

Methods:

Three focus group interviews with 22 clients who sought medical advice at primary health care clinics. The data were analysed thematically.

Results:

Findings were summarized in three main themes: 1) Clients’ experiences with general practitioners; 2) Causes of not seeking advice at clinics; 3) Clients’ perceptions of the physicians’ capabilities and professionalism. There was comfort and full access to primary health care (PHC) service, although clients were not satisfied sometimes. This is due to the absence, inadequate, and poor quality of the service. This may lead to several visits without getting the service required.

Conclusion:

Listening to the experiences of the clients and users of PHC identifies what works and what does not work in the service and improves the quality. Measuring the experiences of the users and the satisfaction of the clients is an important aspect of quality.

1. INTRODUCTION

Healthcare is a high-contact practice, that demands great efforts to maintain credibility by providing high-quality service [1]. Service quality is a key measure of both client satisfaction and trustworthiness [2-4]. What contributes mainly to high-performing health services is the quality of PHC services [2, 4, 5].

There is an important role for PHC within the larger health system in any country. The health systems that are based on PHC are more effective in terms of clients’ outcomes at the population level [6-9]. They are more equitable, more efficient and satisfy their users. They play a key role in improving the performance of the system and responding to people’s health needs demands and expectations [7, 10, 11]. It works well in developed countries as well as in less developed with fewer resources.

This paper reports the experiences of primary health service users in Jordan. The objectives were to gain insight into clients’ perceptions of primary health services, clients’ attitudes toward accessing the primary health services and why they use or do not use this service in the designated centres rather than secondary health service providers.

1.1. Background

Service users of PHC express a variety of experiences and expectations when assessing it in different countries [1, 10, 12-15]. Take the access to health services as a measure of those experiences and expectations. e.g., in countries such as Nigeria, cost and income were the main determinants of access to primary care [2, 15]. A study from the United Kingdom (UK) showed that access to primary care was affected by non-practice-related factors such as age and ethnic group. These two factors alone were significant measures of a client’s satisfaction. The same study also highlighted the ability to make a quick appointment with a particular general practitioner (GP) was another important measure of access to primary care [13].

A recent systematic review of access to primary care included 20 qualitative studies with a total of 689 clients from 10 countries [16]. This review identified four main domains affecting access to primary care: i.e., communication; coordination; relationships; and personal value [16].

Studies from the Middle East on access to primary care are scarce and clients’ experiences are not the focus. A cross-sectional quantitative study was conducted in the city of Irbid, located north of Jordan, in 2014. It investigated patterns and factors associated with the utilisation of PHC among 190 elderly people. The PHC services were used by 68.4 per cent of the sample in the preceding six months, and by 73.8 per cent in the previous 12 months. The presence of chronic illnesses was the strongest predictor for PHC utilisation [17]. Although the participants did not give their experiences, the study was limited to one city and the elderly population.

Another study identified the main problems facing the Iraqi PHC and then prioritize the needed changes [18]. It was based on a qualitative survey of 46 primary care managers, public health professionals and academics in Erbil, north of Iraq. The study provided recommendations for improving the PHC system. e.g., reorganisation action of the services and leadership, regulation of public-private practice, improving prevention and health education, and provision of continuing professional training and development [18]. While this study resulted in the identification of structural improvements to the PHC delivery system, most improvements would probably not have been recognised by the clients.

In Jordan, there are a variety of potentially negative impacts on the delivery of PHC [19, 20]: a) non-aligned health care providers in PHC provision toward a common goal; b) new graduates work as general practitioners upon completion of one year of internship without receiving post-graduate training in family medicine or general practice. c) secondary healthcare services receive unnecessary referrals from primary care; d) significant delay in diagnosis of breast and colorectal cancer amongst symptomatic clients which leads to diagnoses at more advanced disease stages.

Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion [21] reported that PHC services are the foundation of healthcare, the first to deal with disease exposure and treatment, dealing with chronic diseases, and offering preventive care. However, the client’s access to PHC varies due to the cost of service, distance and travel to the service provider, the language of the service provider and managing time off work to receive the service. These measures probably do not give a clear picture of many Jordanian clients who seek PHC services in the hospitals. Hospital services compared to PHC centres are considered expensive, crowded and geographically far from the residents’ local area. The question that we seek to answer, is why some clients use PHC services and why others go to hospitals to receive this service or part of it?

Research is needed to inform health systems and policymakers about the gaps in health, the quality of the service and the performance of health services. Evidence from research is required to gain insights into these gaps and how to translate the evidence into policies and decisions. One of the key issues in PHC is the assessment of its quality and performance by asking the service users and exploring their experiences. Therefore, we ask here: what are the experiences of the clients (users) of PHC service in Jordan?

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. The Study Design And Methods

This study adopted a qualitative research design to investigate the experiences of PHC service users [22]. Focus groups were useful because they combined interviewing and group interaction especially when the researcher wanted to investigate clients’ opinions [23, 24]. During conduction, we found the interaction between participants produced data and ideas that could not be revealed in an individual interview.

2.2. Setting

The study took place in three Jordanian cities, Amman, Irbid, and Al-Karak. Recruitment was done from primary care attendants and purposeful selection of clients who refer to secondary care as PHC service providers from both the Ministry of Health (MoH) clinics and the private sector.

2.3. Study Population

The target clients selected to participate in focus groups were selected purposefully because the intention is not to make inferences about a larger population, but to understand how clients in the focus groups think and talk about their use of primary health services. Therefore, we set up focus groups to explore diversity and determine the range of views, instead of ascertaining representativeness. The focus group (FG) participants were similar because all were users of primary health services; this maximised the comfortable feeling to express their opinions. the interaction between participants during FG motivated explaining, scrutinising, and rationalising of their views.

The recommended size for FGs is six to eight participants to avoid limiting the extent and range of experience that can be drawn upon or silencing group members from revealing their views [24]. In total, 22 clients attended three FG interviews: The first FG was attended by seven participants from (Amman) in the central region; the second FG was attended by seven from the southern region, and the third FG was attended by eight from the northern region.

2.4. Data Collection

The FG interviews were moderated by one of the authors’ AN with two assistants trained in recording notes and observing participants. The interview started with a broad open question then all FG interviews with clients were conducted following specific instructions described in an interview guide. Probing questions were used when necessary to guide the discussion and focus the group members on understanding the phenomena involved. FG interviews were conducted in health centres’ meeting rooms and took an average of 60 minutes. All interviews were recorded digitally, and participants were informed about recording during the instructions and before signing the consent form.

At the beginning of each FG, the moderator AN sets ground rules for the participants that will be heard during the discussion and should be kept confidential. This was to confirm the protection of confidentiality which was not controlled by the researcher during the discussion. Pseudonyms were used for the quotations from the participant’s FGs to confirm confidentiality.

2.5. Trustworthiness

Three FGs conducted as those achieved segmentation and saturation of data particularly when the length of the interview was not restricted. Three categories were selected one from each region as a segment. However, after conducting the first FG the moderator AN noticed the repetition of data yielded during the second FG. There were no new insights gained during the third FG; this confirmed saturation. Scientific rigour for the qualitative data was achieved through procedures to ensure the trustworthiness of data, such as dependability audit, three researchers debriefing (credibility), dense description of the sample and peer review to assure transferability and confirmability [23].

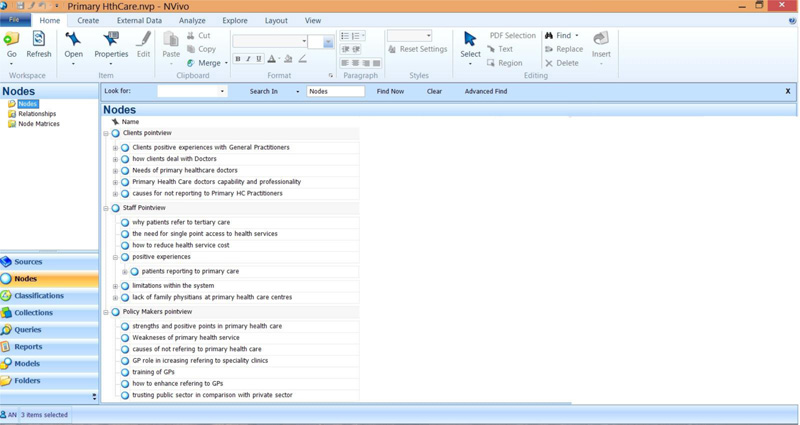

2.6. Data Analysis

The qualitative data analysis was conducted by thematic analysis using NVivo 9.0 (QSR International). Overall, one researcher AN was the primary analyst of the collected data and started the analysis immediately after the first FG. Thematic analysis of the respondents’ statements provided information that was used for the development of free codes. In a series of meetings, the project team discussed those codes, categorised them, and then agreed on final themes based on the data from FG interviews. Analysis was conducted by listening to the recordings of the FGs several times and then coding the voice-file sections that contained the subthemes. After collecting all codes for all FGs, two of the researchers categorised the codes independently. Afterwards, they agreed on a universal set of codes. This was followed by deriving final themes from the categories (Fig. 1).

The interview was recorded and coded by the AN. Double-checking for accuracy of the free codes performed by MA and GK both have qualitative research experience. Data analysis is conducted initially on the Arabic voice recordings of the interviews. The codes, categories and themes were extracted in English. During the writing of the findings section, all final identified free voice quotations were translated into English. Quotations were transcribed from the translated emerging themes into English. Confirmation of the translation is checked by giving the final English themes to a professional bilingual translator to do a back translation into Arabic. Complete congruence between the Arabic and English versions of the themes was obtained.

2.7. Ethical Consideration

The study was approved ethically by Mutah University Ethics Committee (Ref. No. 20162). The reported methodology and data conform with the ethical standards of the committee responsible for human experimentation at Mutah University, and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2013 (http://ethics.iit.edu/ecodes/node/3931). The Higher Council of Health Council also informed the Directors of Health and Directors of involved health centres and hospitals in Amman, Karak, and Irbid to facilitate the conduction of this study (Ref. No. HHC/General Study/317). All participants were volunteers and consented in writing for taking part in this project. Clients who participated in this study volunteered to take part in the FG discussions when invited by their physicians and after reading the information sheet and consenting to take part. The focus group discussion was voice recorded digitally. Their personal information was removed and given pseudo names during data analysis. Apart from the invitations introduced by the physicians and the support letters by health directors, no contribution from the public and the clients in the study design or conduct of the study, analysis, or interpretation of the data or preparation of this manuscript.

3. RESULTS

The three focus groups were conducted in Amman (middle region), Irbid (northern region) and Karak (southern region). The moderator of each FG did not interfere in the selection of the participants and did not determine the number of how many to attend. Invitations from directors of health in each region were sent to 15 to 20 clients, but those who volunteered for each FG were around ten and then only 7 or 8 attended. Most of the participants were females in southern and northern regions (see Table 1 for detailed demographic data). Few participants were not Jordanians, but residents within catchment areas of the health centres where we conducted the focus groups. Most were residents in urban areas. We noticed that rural residents have a long distance from health centres. The age groups of the participants represent middle age rather than elders probably some of them receive a health service and collect prescriptions for their relative elders. The females mostly refer to health centres to access women and child health services. Some females were accompanied by a child during the meeting.

The majority of participants positively perceived the short waiting time and availability of same-day care on most occasions when referring to health centres. However, the minority (those who seek primary health service at service providers classified as secondary) recognise the proximity of service to their residence area. On the other hand, most of the participants expressed dissatisfaction regarding the infrequent unavailability and incompleteness of the primary health services in health centres.

Key findings from the interview were categorised by three main themes: Client’s experience at the clinic; Causes of the client not seeking advice at the clinic; client’s assessment of primary-care physicians’ capability and professionalism at the clinic. Each theme was reported based on clients' perspectives (Table 2).

| Pseudo Name | Age (years) | Gender | Level of Education | Place of Residence | Urban/ Rural | Distance of Health Centre | Nationality |

| Nawal | 55 | F | Primary | Amman | Urban | 1km | Jordanian |

| Hadya | 32 | F | Secondary | Amman | Rural | 3km | Syrian |

| Maher | 38 | M | University | Amman | Urban | 0.3km | Jordanian |

| Mohammad | 41 | M | Secondary | Amman | Urban | 1.5Km | Yamani |

| Rami | 36 | M | University | Amman | Rural | 4km | Jordanian |

| Mamdouh | 53 | M | Secondary | Amman | Urban | 2Km | Jordanian |

| Wedad | 28 | F | University | Amman | Urban | 2.5km | Jordanian |

| Wesam | 37 | M | University | Irbid | Urban | 3Km | Jordanian |

| Wardah | 45 | F | Secondary | Irbid | Urban | 1km | Jordanian |

| Reham | 36 | F | Secondary | Irbid | Urban | 1.3Km | Jordanian |

| Arefa | 54 | F | Primary | Irbid | Rural | 5Km | Syrian |

| Yousra | 48 | F | Secondary | Irbid | Rural | 4Km | Jordanian |

| Hana | 33 | F | University | Irbid | Urban | 2Km | Jordanian |

| Adebah | 49 | F | Secondary | Irbid | Urban | 2.5Km | Jordanian |

| Sana | 46 | F | University | Irbid | Urban | 3Km | Syrian |

| Tyseer | 50 | M | Primary | Karak | Urban | 3Km | Jordanian |

| Rehab | 43 | F | Secondary | Karak | Urban | 2.5Km | Jordanian |

| Naser | 46 | M | Secondary | Karak | Rural | 3Km | Jordanian |

| Seham | 50 | F | Primary | Karak | Rural | 6Km | Jordanian |

| Asma | 43 | F | University | Karak | Rural | 7Km | Jordanian |

| Raeda | 38 | F | University | Karak | Urban | 2Km | Jordanian |

| Radi | 52 | M | Secondary | Karak | Urban | 3Km | Syrian |

| Theme | Theme Categories | Subthemes |

| Clients experiences with General practitioners Practitioners capability |

Professional behaviour of doctors | Know the case in advance |

| Appropriate follow up for clients | ||

| Doctor knows the social and economic background of the clients | ||

| Friendly communication with clients | ||

| Case management | Clients preferences in reporting to doctors | |

| Efficiently dealing with clients | ||

| Less time waiting to receive service | ||

| Time-savings | ||

| Need to get referral from health centre | ||

| Cost of treatment is less expensive | ||

| Primary healthcare doctors’ capability and professionalism | Inappropriate behaviour and limited communication skills | Lack of duty commitment (e.g. working hours) |

| Unprofessional reception for the patient | ||

| Ineffective treatment of patient’s case | Limited training on chronic diseases or for early detection of diseases such as cancer | |

| Past experience such as wrong diagnosis, or | ||

| not recommending appropriate referral | ||

| Causes for not seeking medical advice from clinic practitioners System services |

Doctors are not well enough trained to provide service | Inappropriate reception from staff |

| Lack of specialists or well-trained doctors to manage their case | ||

| Clients’ worries of complications or deterioration in their case because of delay in referral | ||

| Preventive medicine is not provided | ||

| System-related issues | Referred to private or public hospital | |

| ‘Moonlighting’ (Doctor works in MoH clinic but also has own private clinic) | ||

| Absence of control for the service | ||

| Dr is not available when client visits | ||

| Equipment failure or out-of-order | ||

| Service provided only if mediator* found | ||

| Limited trust in available medications | ||

| Insurance problems | ||

| Not all services are available | ||

| No availability of lab, X-ray or medications |

Source: study data from focus groups

3.1. Clients’ Experiences with GPs

One of the identified key positive factors about access to PHC in Jordan was the short waiting time and availability of same-day care on most occasions. The PHC centres provide a wide range of services to the community and are easily accessible to people in all regions and locations. Participants reported that the main advantage of PHC in Jordan was the quick access and comprehensive coverage. Reported services were treatment of acute conditions, the possibility of early detection of chronic diseases, mother-and-child care, and immunisation. Another advantage was providing services close to where the clients live, especially for residents in peripheral areas. Moreover, the clients reported the friendly relationship between PHC physicians and their clients and the trust they have built with their clients. One of the participants remarked on efficient dealing with clients, knowledge of their social and economic status, saving their time and resources, and finally emphasised the cooperation of physicians in the follow-up process.

“Some health professionals work with consciousness. I refer to one doctor who followed up on my son’s case and I prefer not to change this doctor. This is preferable because the doctor knew the treatment of my son.” (Male, Middle region)

Another client reported an interesting positive experience with a health centre in the southern region, she said:

“I have experience with primary health centre doctor who is always ready for his clients. He always prepares their prescriptions in advance, once the client visits him the prescription is ready in a bag [of medications] to pick up. He was in this health centre for 20 years and knew everyone well. If you ask him about any client, he will tell you the entire story and tell you the story of the client’s family members. …It is easy to deal with this doctor.” (Female, southern region)

3.2. Primary Healthcare Doctor’s Capability and Professionalism

Participants reported that there are major contributions for GPs at primary health services. They know the case in advance, deal efficiently with clients, know the social and economic background of their clients, communicate friendly with clients, save clients’ time and money, and provide appropriate follow-up for clients.

“In this health centre, the doctors deal friendly and respect clients, while in the hospital’s doctors have a load of duties and after midday get bored of providing service.” (Female, Northern region)

The GPs in the PHCs are in contact with their clients and know them usually personally. This leads to understanding their client’s behaviours and accepting their frustration professionally. A female participant recognised the compassion attribute for those GPs and stated:

“When clients visit the doctor, they are usually frustrated, tired, and nervous; doctors receive them calmly, in open heart and mind, and absorb their nervousness.” (Female, southern region)

Although there are positive attributes for the GPs in the PHCs, many clients choose not to refer to these primary health centres and go elsewhere. In the following theme, the study reports why clients seek health care in the secondary health system or the private sector.

3.3. Causes of not Seeking Advice at the Primary Health Level

Participants identified some potential barriers to access to PHC in Jordan. They reported some weaknesses and limitations are either related to the system, staff, or the service itself. The system-related factors included poor compliance with working hours, insurance causes, moonlighting (doctors have dual jobs; for example, work in health centres and have a private clinic at the same time), service provided only if a mediator is available, and limited available services.

Barriers related to staff included: inappropriate reception from staff, some doctors not complying with working hours, lack of speciality or well-trained doctors to manage their cases, and they have not assured the competency of some doctors who provide health care to them. A male participant stated:

“I visited a doctor in a health centre at 11:30, the nurse said we finished duty today, the doctor is not available now, then she asked me what is your complaint? Then she picked a medication from the pharmacy, and she gave it to me. That is all.” (Male, Southern region)

Participants also mentioned points related to service weakness including limited preventive medicine services, frequent equipment failure or being out of order, limited trust in the effectiveness of available medications, and delay in referrals. Some clients reported worries of deterioration in their case because of delays in referral to hospitals.

“I referred to an X health centre, my daughter was complaining of her ear, the doctor asked me; what shall I do for her. I said I do not know. She replied, shall I examine her? My daughter kept crying. Then the doctor said: as she would not stop crying no need to examine the baby.” (Female, southern region)

The clients emphasised “understaffing” as a key barrier to PHC improvement in Jordan. They hypothesised that understaffing at PHC is leading to inappropriate behaviour and limited communication skills, unprofessional reception for the client, ineffective treatment of the client’s case, and delayed or inappropriate referral.

Another major identified limitation of PHC services in Jordan was the lack of control over access to secondary care. Some clients visit different service points and receive similar treatment for the same complaints. The system fails in detecting those clients who get the same service several times for the same health problem.

3.4. How to Improve PHC Service in Jordan

Participants were also approached to get their opinion on methods of improving access and services at PHC in Jordan. Most indicated the need to focus on staffing issues and provide more training for PHC staff, mainly for GPs.

“There is a need to provide health centres with experienced doctors not the newly graduated, and to give them enough training.” (Male, southern region)

The three themes will be discussed in the following section in light of the previous literature.

4. DISCUSSION

In this qualitative study, we were able to understand how clients experience the access to PHC in Jordan through focus groups of clients attending governmental and private sectors: Clients’ experiences with PHC and mainly the GPs in Jordan, causes of not seeking advice at PHC services, and PHC doctors’ capability and professionalism. The findings are important at the micro level mainly (doctor-client relationship), however, the Meso-level (health facility management) and the macro level (governance) would find justification for areas of improving the PHC system.

Our findings are consistent with findings from a recent systematic review [16]. This review concluded that the main themes related to access to primary care are barriers to care, communication, coordination, relationships, and personal value.

Results related to areas of strength of PHC in Jordan such as quick access are consistent with a recent study from the UK, which concluded that the ability to make a quick appointment with a particular general practitioner was an important determinant of access to PHC [13].

Some clients visit different service points and receive the same treatment for the same complaints. This is probably one of the causes of overloading health services and increasing the budget for medications in primary care. Moreover, the lack of a control system in place justifies the reported finding that clients prefer going to hospitals without seeking medical advice from PHC centres. In Jordan, the electronic health system programme (HAKEEM) is progressing well in applying electronic databases at health care centres [25]. This would help in the future in the prevention of this weakness in the system.

Clients agreed on the fact that more training is needed for PHC staff, mainly physicians. In most western countries, new graduates cannot work as GPs without having at least a 3-year postgraduate training programme in general practice or family medicine. The same approach has been initiated in neighbouring countries to Jordan. We expect that such a programme would provide high-quality GPs leading to improving access to primary care and reduction of the load on secondary health care services.

4.1. System-related Issues

Providing primary health services in secondary health service centres is expensive for the government and the clients altogether. It is a core responsibility of the government to ensure the availability and accessibility of quality primary health services on an equitable basis. Health-care leadership, innovations, family practice, inter-sectoral collaboration, effectiveness and accountability are key steps toward achieving this goal [26].

In Jordan, PHC services are mainly delivered by general physicians who are not properly trained to deliver people-centred healthcare services. There is a persistent shortage of Family Doctors. To compensate for this, it is recommended that GPs undergo specific training to bridge the gap in family practice knowledge and skills and to actively participate in Continuous Professional Development (CPD) programmes.

Accountability mechanisms and a rigorous supervision system in place could motivate healthcare providers to commit to their work in terms of working hours, quality and quantity of healthcare services, provider-client encounters and continuity of care [26-29].

With the relatively high public health expenditure in Jordan, achieving universal health coverage (UHC) is not far. According to the 2015 census, 55% of the population was covered by any type of health insurance scheme [30]. However, given the fragmented health sector and the complex governance layout in Jordan, reforms are needed in healthcare financing mechanisms to achieve UHC. In addition, effectively allocating funds and applying health economics principles in healthcare financing, using different models of public-private partnership, and applying information technologies may as well support reaching this goal.

4.2. Limitations

The number of focus groups was limited because of budget, however, the researchers found it enough as no new data was generated after the 2nd one and number of participants in each group was suitable and one health system governing the service. Therefore, if the same study is applied elsewhere, consideration for the health system and social differences should be counted.

Although this study reports important information about the quality and experiences of patients regarding primary health care utilization, we indicate that the setting was public sector only because primary health care is mainly provided by it in Jordan. However, few participants from the private sector have already taken part, but it seems they utilise the public service at the same time. Therefore, it is recommended to consider conducting a study in a private sector setting and another one for welfare and not-for-profit organisations which provide services for a considerable proportion of refugees.

This study like all qualitative studies was difficult to obtain strict conclusions and generalise the findings in comparison to those following the quantitative paradigm. Although the sample was selected purposefully, the researchers did not interfere directly in selecting them, but the gatekeepers were informed of inviting participants who are informants and willing to give details as much as possible. The moderator AN was able to give every participant enough room to give his or her views freely and the researchers conducted a thorough check of the rigour. One point noticed during this check when revising the notes for the FG conduction in Irbid; the facilitator discovered after the session ended that one of the participants was an employee in the same health centre who was a client on the day of invitation to FG. The coding and analysis of the interview assure the other participants did not recognize her and she had no influence on the opinions of others during the discussion. We presume, that if they knew her previously, may affect the opinions of the participants during the discussion. Therefore, this should be considered in any future study locally or internationally.

CONCLUSION

While this qualitative study’s conclusions are applicable to Jordan’s PHC, other low-income countries may find it explains some aspects of their local situation. The clients’ experiences in utilising primary health services in Jordan shed a light on access to primary health services. It clarified how clients access the primary health services and why they used or do not use this service in the catchment area health centres. Primary health services in the public sector are widely used in Jordan because it’s the main service provider and there is an ease in access to those services including the low cost. However, clients expressed dissatisfaction because some of their health needs are not met. Therefore, most of them refer to more expensive secondary health services which accept them due to the absence of an enforced referral system. This dissatisfaction is due to the absence, inadequate, and poor quality of the primary health service. This is implied from the patient’s several visits without getting the service required. Hence, some clients prefer to get the service from the emergency room and outpatient department in the hospitals, which are also accessible without restriction or referral from PHC. Major revision for the design of the health systems based on primary health care is required. This should include enough recruitment of qualified health professionals and provision of training for them. Once, the quality of PHC service is improved, then establishing a system for referral to secondary service is required. Improving primary health services has a priority for any fully functioning and strong health system.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| GP | = General Practitioner |

| FG | = Focus Group |

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

The study was approved ethically by Mutah University Ethics Committee (Ref. No. 20162).

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

No animals were used that are the basis of this study. The reported methodology and data conform with the with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2013 (http://ethics.iit.edu/ecodes/node/3931).

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Informed consent was obtained from the participants.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIAL

The data supporting the finding of the study are available within the article.

STANDARDS OF REPORTING

COREQ guidelines have been followed

FUNDING

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest financial or otherwise.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.