All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Factors Predicting the Holistic Health Status of Cambodian Migrant Workers in Thailand

Abstract

Purpose:

The overall health of Cambodian migrant workers is low. This study aims to describe the holistic-health status (HHS) of Cambodian migrant workers in Thailand.

Methods:

Three hundred four participants participated in this cross-sectional survey study. Participants completed the HHS questionnaire developed from the WHO Quality-Of-Life assessment and modified the Migrant Farmworker Stress Inventory. Descriptive statistics and multiple regression analyses were used.

Results:

The study identified that social value and adaptation, or how people interacted and adapted to their community, was a significant predictor of HHS (p = .003). Other factors such as financial status, living and working environment, healthcare service and accessibility, and migrant policies were insignificant in the model.

Conclusion:

Social value and adaptation predicted HHS in our sample of Cambodian migrant workers. Other factors such as financial status, the living and working environment, health care services and migrant policies did not contribute to HHS in this sample.

1. INTRODUCTION

The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) integration is changing this region's economic and cultural environment, particularly by developing the economy in each country. The ASEAN-Integration Agreement is focused on the free flow of products, services, capital investments and skilled workers through a single market. The Cambodian gross domestic product (GDP) is the lowest of any country in the Greater Mekong Subregion (GMS), as well as in the ASEAN, so there is a large flow of people seeking a new life and better income [1]. The International Organization for Migration (IOM), a part of the United Nations System working and leading as an inter-governmental organization, reported that there were about 4-to-5 million migrant workers in 2021 [2], which reflects an increase of 2 million workers from 2020 [3]. The previous studies indicate that low-skilled workers are entering Thailand due to international relations, government policies and memoranda of understanding related to the free flow of workers among countries. The increasing number of foreign migrants also increases problems related to health and incidences of abuse, violence and trafficking. Such large numbers of migrant workers may lead to violation and sometimes exploitation and trafficking of the workers [1].

Several authors have highlighted the workers' poor working conditions, healthcare needs, and human rights abuses [1, 4, 5]. The ILO normally refers to workers covered under the worker’s fundamental rights [3], in line with research this research [6]. These results showed that migrant Cambodian workers in Thailand had a poor quality of life and moderate-to-high levels of stress and symptoms of depression.

Sirgy and Lee [7] identified that work-life balance is an important factor in overall quality of life. Work-life balance was explained by Greenhaus et al. [8] and was cited in Sirgy and Lee [7] as a sense of satisfaction with the nature of one’s work, engagement and non-work roles, or personal effectiveness regarding work independence or dependence. This model explains how the nature of one’s working life affects life satisfaction or quality of life [7]. Quality of life is a response to the accelerating environmental problems and is the link between the person with an objective dimension, known as the concept of holistic quality of life [9].

Moreover, the importance of health-related quality of life and well-being are the goals of promoting quality of life, healthy development, and health behaviors [10]. The WHO states that quality of life is affected by an interaction of an individual's health, mental state, spirituality, relationships and environmental elements [11]. Previous studies [12] found that people's holistic-health status (HHS) depends on socioeconomic status, advanced information and technology, and attitudes toward their own social and cultural values.

1.1. Holistic Health

The Oxford Dictionary [13] defines the general meaning of holism as an interconnection of the body as a whole, consisting of more than just a single part. The terms ‘holism’ and ‘holistic’ consider that something consists of or is viewed as having many dimensions, and it sees those things as a whole rather than just a part. “Holism” and “holistic” define health in different ways; however, they all view health as a whole, which refers to the accumulation of many parts [14].

Health is defined by the WHO as a “state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity” [15]. The modern definition of health has been expanded accordingly regarding socialization and modernization. Health can be viewed according to many dimensions, such as the balance of the body, harmonizing and a system of the integration of body and mind, which has been extended as holistic health [16].

Jaheim et al. [17] addressed the related term ‘holistic care,’ indicating that it interacts with medicine and nursing purposely in patient-centered care; it is stated as ‘holistic care.’ In other words, holistic health is an approach to life usually characterized by many factors, such as socioeconomic status; different cultures; people’s perceptions, attitudes and beliefs; and their living and work environments [12].

1.2. Holistic-Health Definition and Models

1.2.1. Holistic Model

Robinson [18] stated that the holistic model is useful and used in healthcare services to understand and guide practice. This model consists of several dimensions: body, mind, spirit, emotions and society. This model's individuals are at the center, including those using healthcare services. For example, the experience of stress affects the whole individual. Likewise, physical problems may lead to emotional issues expressed by passive participation in society or other related issues. A holistic model considers health as a whole rather than just one part [18].

1.2.2. Theories of Holistic Health

Holistic health is a theoretical model developed by Proeschold-Bell et al. [19] aiming to capture the factors affecting the health of a specific group of people. The concept of this model is composed of three main aspects: 1) condition, which refers to the integration of the individual within their environment; 2) mediator, which relates self-care and coping responses to one’s stress, together with physical, mental and spiritual elements; and 3) outcomes, which are related to the quality of life, physical condition, spiritual well-being and mental health status [19].

1.2.3. Biopsychosocial Model

The biopsychosocial model of George Engle, 1977, aimed to show the relationship between one’s body and a person’s sense of well-being – that there is a strong relationship between biological and psychosocial factors [20]. The model plays an important role psychologically and provides a wide range of understanding of people’s interactions, especially regarding health-related issues or health policy development

1.2.4. Biopsychological-Spiritual Model

This model added the spiritual element from older models, which stated that spirituality was another important factor in terms of health. The author explained that the spiritual component differs from the sociological aspect and involves practices such as prayer or meditation to achieve health and health-related effects from the body-mind-mental, social and spiritual aspects of one’s existence [21].

1.3. HHS of the Foreign Migrant Workers

1.3.1. Working Conditions and Health Service Accessibility

Recent research has indicated that the health of migrant workers is affected by social integration and that this integration influences their health behaviors [22]. Foreign migrant workers may face many problems regarding their health conditions and seek health services after migrating to Thailand. Usually, this group reports abuses and violations against them. The victims are often physically and psychologically abused. Also, the study found that they lack access to medical treatment, seek healthcare services only with difficulty and experience social-service inequality. Healthcare service accessibility became an issue to protect international migrant workers. Thus, there have been reports on the inequality of care and treatment of local Thai people and migrant workers. The Thai government, as well as private agencies and organizations, have been working to improve the health status of migrant workers. In addition, these same spokesmen have also reported unequal treatment of Thai people and migrant workers residing within the same community [22].

Therefore, the definition of HHS in this study refers to the condition of the physical health, psychological and emotional health, social relationship and spiritual health, and environmental health of the Cambodian migrant worker.

1.4. Factors Influencing Holistic Health Status

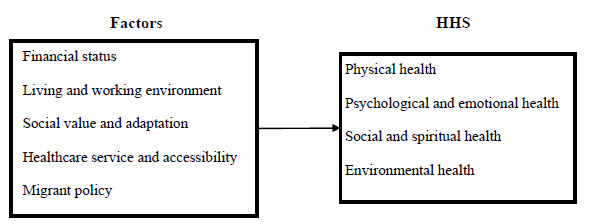

Factors affecting the holistic health status were identified through a literature review and include five major variables: financial status, living and working environment, social value and adaptation, healthcare service and accessibility, and legally established labor law and migrant policy. Financial status is defined as the perception of the income of Cambodian migrant workers for their daily living. The living and working environment is where people live and work, which plays an important role in their lives [23]. The living and working environment of the Cambodian migrant is another essential factor in promoting healthy life. Most of the low-skilled workers work in bad weather, perform hard physical work that is both risky and dirty, and work for less pay than skilled workers. Understanding the living conditions and working environments of low-skilled workers, particularly Cambodian migrant workers, is very important to employers and the Nation’s policymakers. Social status, cultural disparities and environmental issues all have a significant impact on the HHS of people [24, 25].

1.4.1. Social Value and Adaptation

Social value is an aspect of human well-being. There is the social value of a place where people are exposed to their surrounding environment [26, 27]. Terziev 2017 [27] stated that social adaptation is composed of how people interact with others in their community. Leaving their home country or migrating from their home to their local rural areas and moving to a city like Bangkok or an entirely new workplace is not easy for workers.

1.4.2. Healthcare Services and Accessibility

People must have access to a place where they may receive the healthcare and comfort they need for their physical and psychological well-being [13]. Currently, there are legal mandates for healthcare services and accessibility for international migrant workers; however, there are still inequalities. Thailand’s government policy and private agencies organizations have been working to improve the health of foreign migrant workers, but they also reported on the inequality of treatment between Thai people and foreign migrant workers in community healthcare services. Accessibility for the workers is another crucial factor in predicting the HHS of Cambodian migrant workers.

1.4.3. Migrant Policy

This policy is defined as how people are expected to go through the process or complete their paperwork per the Country’s law on migration. The migrant policy is a factor that may influence the holistic health of Cambodian migrant workers and is defined in the Legal Labor Law and Migrant Policy.

According to the literature above, the conceptual framework is shown in Fig. (1).

2. RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

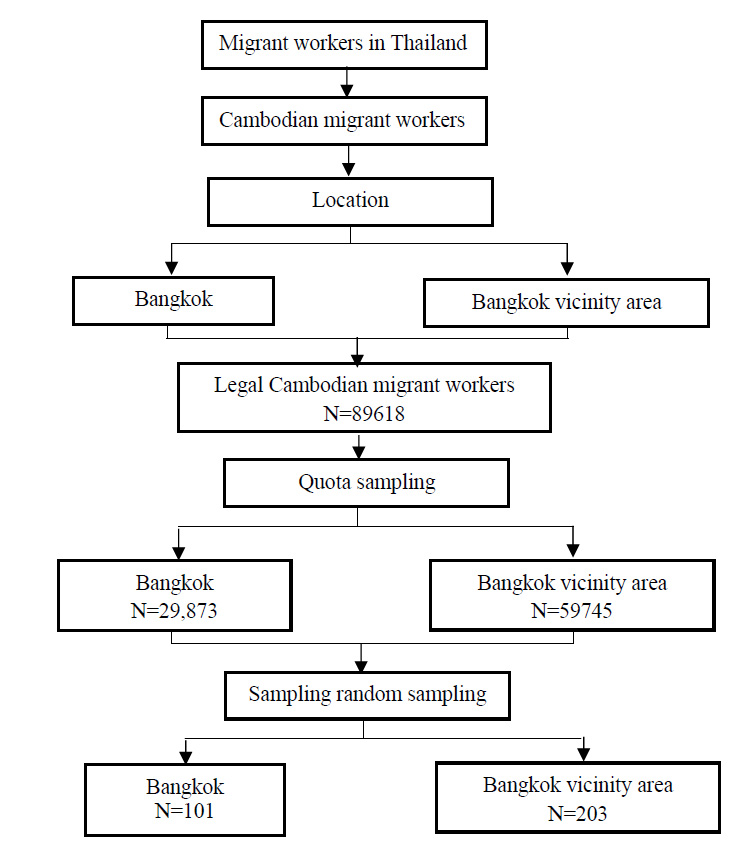

This cross-sectional survey study was designed to explore and identify the health-related quality of life and HHS of Cambodian migrant workers. G*Power version 3.1.9.2 analysis and a multiple-regression statistical test were used to calculate the sample size. The sample size calculation used the same effect size reference as the previous study, with R2 = 0.14 [12, 28, 29]. A confidence interval of 0.95 and effect size = 0.10 were used in the calculation. There was a total of 10 predictors with alpha level = 0.05. The G*Power calculation resulted in a sample size of 254 workers. An additional 20%, or 50 participants, were added to account for participation refusal and missing data or errors. The final sample size was 304 workers. After collecting data from June 2021 to September 2021 from the 304 participants, the missing and incorrect data and outliers were handled using list-wise deletion. In total, there were 290 participants with complete data.

The multistage sampling method was used to select the number of samples from Cambodian migrant workers working in Thailand. Step one was to define the group as legal Cambodian migrant workers; step two was the quota sampling from each group for the study: Bangkok and Bangkok vicinity area; and step three was random sampling from stage two to self-administer the questionnaires by a Google form (N=304), as detailed in the following (Fig. 2).

2.1. Instrument Development

The instrument used in this study was derived from the conceptual framework to construct the domain and content from existing theoretical definitions. Items were generated using the concept of health [15], the WHO quality-of-life assessment (WHOQOL) by Group [30] and a modification of the Migrant Farmworker Stress Inventory (MFWSI) by Joseph [31]. Using multiple instruments ensured that this instrument would capture every aspect of holistic health and health-related quality of life.

The questionnaire was developed using the forward-backward method from the Khmer language back to English to verify the meaning and accuracy. Cognitive interviews were conducted with five Cambodian workers, respectively, to ensure the questions were being understood. The index of item objective congruence (IOC) was used to indicate content validity. The IOC indices for each item were reported to be between 0.60 and 1.00. Appropriate modifications to the questions were made. Cronbach’s alpha was used to measure internal consistency reliability and was found as .98.

2.2. Instrument Structure and Data Collection

2.2.1. Three Instruments were used in this Study

The first instrument was a demographic form. Standard demographic information such as age, gender and salary were collected. The Migrant Worker Stress Inventory (MWSI) consists of 28 items and measures the stress associated with individual items. The response format ranges from 1 to 5, with 1 indicating that the individual has not experienced stress and 5 indicating that the item was severely stressful. The third instrument developed from the WHO Quality-Of-Life assessment is the HHS of the migrant workers. This instrument measures holistic health and is comprised of 34 items. The response format ranges from 1 to 5, indicating accordingly reposed to the question. Data collection was completed using a Google form encrypted for every single entry with the label “No Duplicates” in the Google form builder. Each participant was permitted to submit only one answer on any one of the devices. Data collection was completed within the 3 months from June 2021 to September 2021.

2.3. Data Analysis

This study used different types of analyses for different purposes: SPSS Version 22 was used to analyze the data. Descriptive statistics, such as means and standard deviation, were used to analyze the level of the HHS of Cambodian migrant workers. Stepwise multiple regression analysis was used to explore which factors could predict the HHS of the Cambodian migrant workers used in a similar paper by Ruchiwit [12].

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Twenty-four participants were in the agriculture/fishery group, 66 were in the manufacturing/construction group, and 200 were in the services and sales group. The average age of the participants was 32.70 years (SD=7.55 (range= 18 and 60 years). Their average monthly net salary was 353.26 USD (SD=86.34) (range = 150 and 650 USD). Their average time worked in Thailand was 4.23 years (SD=2.23).

Participants rated financial status, living and working environment, and social value and adaptation as somewhat stressful, with the mean scores ranging from 3.04 to 3.13. The domains of healthcare service and accessibility and migrant worker policy were rated as moderately stressful, with the mean scores ranging from 3.57 to 3.74, as shown in Table 1.

| Variables | Min | Max | Mean | SD | Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent Variables | |||||

| Financial status | 1.00 | 5.00 | 3.04 | 0.89 | Somewhat stressful |

| Living and working environment | 1.33 | 3.78 | 3.07 | 0.44 | Somewhat stressful |

| Social value and adaptation | 1.00 | 4.43 | 3.13 | 0.53 | Somewhat stressful |

| Healthcare service and accessibility | 1.00 | 5.00 | 3.74 | 1.23 | Moderately stressful |

| Migrant policy | 1.00 | 5.00 | 3.57 | 1.21 | Moderately stressful |

| Dependent Variables | |||||

| HHS | 2.21 | 3.88 | 3.09 | 0.29 | Normal |

| Physical health | 2.27 | 4.00 | 3.22 | 0.31 | Normal |

| Psychological and emotional health | 2.14 | 4.71 | 3.30 | 0.32 | Normal |

| Social and spiritual health | 1.43 | 4.43 | 3.23 | .47 | Normal |

| Environmental Health | 1.78 | 4.33 | 2.66 | .45 | Normal |

Using stepwise multiple regression analysis, age, sex, education, job type, monthly income, financial status, living and working environment, social value and adaptation, healthcare service and accessibility, and migrant policy were predictors of HHS. These factors predicted 8% of the variance of HHS (R2=0.08). The correlation coefficient (r) was 0.28, with a statistical significance level of .05. The coefficients in the raw score form (B) and the standardized form)Beta) of social value and adaptation were 0.12 and 0.22, respectively, with a statistical significance level of .05. The constant was 3.08, with a statistical significance level of .05. The other variables affected HHS with no statistical significance, as shown in Tables 2 and 3.

| Variable | R | R Square | Adjusted R Square | Std. Error of the Estimate | F | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social value and adaptation | 0.19 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.28 | 10.48 | <.001 |

| Variable | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Std. Error | Beta | |||

| Constant | 2.77 | 0.10 | 27.74 | <.001 | |

| Social value and adaptation | 0.10 | 0.03 | 0.19 | 3.24 | <.001 |

The enter method of multiple regression analysis using a block forced entry of financial status, living and working environment, social value and adaptation, health-care service and accessibility and migrant policy as predictors of HHS was completed. The statistical results indicated the presence of a statistically significant difference in social value and adaptation p = .003, shown in Table 4.

| Model |

Unstandardized Coefficients |

Standardized Coefficients |

t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Std. error | Beta | |||

| Constant | 2.95 | 0.14 | - | 21.23 | <.001 |

| Financial status | -0.03 | 0.02 | -0.08 | -1.06 | .29 |

| Living and working environment | -0.09 | 0.05 | -0.14 | -1.90 | .06 |

| Social value and adaptation | 0.12 | 0.04 | 0.22 | 2.97 | .003 |

| Healthcare service and accessibility | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.19 | 1.49 | .14 |

| Migrant policy | -0.01 | 0.03 | -0.03 | -0.20 | .84 |

The major finding of this study was that social value and adaptation is the only significant factor predictor of HHS in Cambodian migrant workers. Additionally, financial concerns are at least somewhat stressful for them. Many report that they have been sending money back to their home country. Cambodian migrant workers report that their financial status is critical and requires them to leave their home country to seek a better life with possibly better pay in Thailand [1]. For some reason, their monthly income is not subsidized with an allowance to cover their daily living expenses in Thailand’s modern society.

Study participants reported that social value, adaptation and relationships are major problems that increase stress levels. Statistics presented in this study show that the migrants are stressed in terms of their social value, adaptation and relationships (p=.003). Mills [32] reported that migrant workers have had to learn a new lifestyle and adapt to a new culture and unfamiliar people in the city. Social value and adaptation distress have threatened the well-being of migrant workers and have resulted in them developing psychological symptoms. The social value, adaptation and relationships mentioned in this study refer to the difficulties in their relationships and understanding of life in Thailand, as well as the benefits and personal value, reputations and interactions between the native Thai and Cambodian migrant workers.

Cambodian migrant workers experienced moderate levels of stress related to healthcare services. Although legal mandates for health-care services and accessibility for international migrant workers exist, inequalities still exist. The Thai Government's policies and private agencies/organizations have been directed toward uplifting the health and well-being of foreign migrant workers. There have also been reports from these public and private-sector agencies on the inequality of treatment of Thai people and foreign migrant workers residing within the same community [23].

The results from this study revealed that the significant differences among the independent variables are based only on the social value and adaptation differences in HHS among the five independent variables (financial status, living and work environment, social value and adaptation, health-care services and accessibility and migrant policy). It has been shown that social value and adaptation play an important role for Cambodian migrant workers. This conclusion was established with a statistical significance at p= 0.01 on the model created through multiple regression analysis. The meaning of this finding is that the acceptance level of equality in Thailand is well-regarded among Cambodian migrant workers in Thailand, in line with the previous study in Thailand [31]. It could also be that since this study was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic that social value and adaptation were valued as more important by the migrant workers. Kosiyaporn et al. [33] mentioned that both the private and public sectors in Thailand are trying hard to provide fair treatment for all migrant workers by helping them in their participatory roles of ensuring that they receive services on an equal basis. The International Organization for Migration(IOM) [2] agreed that there are improving signs of inter-cooperation between the Cambodians and the Thai government in solving problems related to Thai migration policy and other legalities to form a standardized migration policy, as required by the ILO and IOM. The International Labor Organization [3], in its 2019-2023 plan, stated that the Cambodian government, under the MOU with the Thai government, is committed to elevating the benefits of Cambodian migrant workers through long-term cooperation and development.

The remaining three independent variables were not statistically significant in this prediction-equation multiple-regression analysis indicating that these independent variables did not significantly affect the HHS of Cambodian migrant workers in this study.

3.1. The Financial Status

The literature review showed that Cambodian migrant workers were moving out of their own country to seek new stable incomes to supplement their financial well-being [1]. Having relocated, the Cambodian migrant workers are receiving better payment for their services than they did in their previous workplace in their home country. It may be that because their financial status is better than it was, they do not perceive it as contributing to their HHS.

3.2. Healthcare Services and Accessibility

As indicated by the study results, the provision of healthcare services and accessibility was not a significant factor in predicting the holistic health status of Cambodian migrant workers. It does not follow sequentially that Thailand is now a medical-tourism country. At the same time, medical services and accessibility are available to all patients at affordable cost and with good quality. Kosiyaporn et al. [33] mentioned that health services and accessibility have now become a “migrant-friendly health service” that has essentially lessened the problem of healthcare access for all migrant workers who have relocated to Thailand since the Thailand policy was first implemented in 2003. There were still reports that migrant workers have difficulty accessing healthcare due to their language and race.

This model predicted only a small percentage of the variance in HHS. There may be factors influencing HHS that were not measured in this study. As mentioned earlier, this study was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic. Perceptions of HHS may have been different during this time than they would have been at other times.

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

This study aimed to examine the HHS of Cambodian migrants in Thailand and to explore key factors affecting their HHS while in that Country. Social value and adaption were significant predictors of the HHS of Cambodian migrant workers. Financial status, healthcare services, accessibility and migrant policy, did not significantly predict the HHS of the Cambodian migrant workers in this study.

LIMITATIONS

The sample size was not representative of the entire number of Cambodian migrant workers presently working in Thailand. The sample does not consider the country's undocumented or illegal migrant workers, which may have biased the results.

RESEARCH RECOMMENDATIONS

More research is needed to explore HHS in migrant workers. Including undocumented and illegal workers in the sample may provide a more realistic view of HHS amongst migrant workers. Although a difficult population to access, their perspective is important. Qualitative interviews focused on HHS would help ascertain specific factors that contribute to HHS.

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

The study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of Thammasat University (Science) (HREC-TUSC) # COA No. 027/2564 following approval by the committee.

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

No animals were used for studies that are the basis of this research. All the humans were used per the ethical standards of the committee responsible for human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2013 (http://ethics.iit.edu/ecodes/node/ 3931).

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Informed consent was obtained from all participants of this study.

STANDARDS OF REPORTING

STROBE guidelines were followed.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

Not applicable.

FUNDING

None.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest of any sort.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thanks to Thammasat University, which has given me a golden opportunity to become a Ph.D. holder with a full scholarship granted under the wise and smart management and administration of Professor Dr. Somkit Lertpaithoon, rector of TU. Special thanks also go to Professor Dr. Manyat Ruchiwit, former dean of the Faculty of Nursing, for her loving guidance and support. In addition, I would like to extend my thanks to the professors and staff of the Faculty of Nursing at Thammasat University for their hard work in fulfilling students' educational needs. They have done so much to help this student become a doctorate-level scholar. Special thanks are extended to the Center for Nursing Research and Innovation at Thammasat University for its support, and sincere thanks are also given to the Thammasat International Affairs Committee for being so supportive and bringing me to TU.