All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Universal Health Coverage in Morocco: The Way to Reduce Inequalities: A Cross-sectional Study

Abstract

Background:

Morocco launched an appeal in 2002 to develop a fundamental law on Basic Medical Coverage. Two systems have been put in place: Compulsory Health Insurance (AMO) based on solidarity and social security contributions; and a Medical Assistance Scheme based on the principle of social protection. The objective of these systems is to achieve Universal Health Coverage (UHC) to attain equity and equality in access to health care.

In the international trend, access to economic and social rights has become a significant concern in public policies. This concept, based on the value of “equity” is now essential in evaluating equal opportunities in social and health systems. More importantly, there is a need to clarify the difference between the terms equality and equity in health. In most cases, reference is made to the definition used in Anglo-Saxon literature (equity, equality, fairness). Therefore, not all inequalities are inequities. The difference between equality and equity lies in that the first term gives the result of comparison without value judgment, while the second makes a judgment that qualifies the result as fair or unfair.

Our study aims to analyze the specific problems related to the healthcare policy focused on allocating the supply of care, and efforts to improve financial accessibility specifically by developing medical coverage. We will present results that reflect the availability and quality of care in Morocco and shed light on the problem of not seeking healthcare for financial, geographical, and other reasons. In addition, we will discuss the difficulties related to the use of care by Moroccan citizens.

The findings of this paper can potentially inform national healthcare policy and add to the small but growing literature on this subject in Morocco.

Methodology:

The methodology is based on research & data taken from official institutional publications from Morocco & United Nations organizations (gray literature) and data derived from articles published in scientific journals.

Results:

Morocco continues to suffer from disparities in the distribution of health practitioners due to an imbalanced distribution of health infrastructure and human resources between rural and urban areas. The Health Map developed by the Ministry of Health and Social Protection in 2016 is a very good tool to monitor the distribution of public health needs in each region, plan the delivery of care, regulate spending, and consolidate regionalization policy to ensure equity in supply and access to health care. At the end of 2021, the national average ratios were 7.3 physicians and 10 beds per 10000 inhabitants. In 2018, more than 60% of the Moroccan population enjoyed basic medical coverage and the Moroccan Government is committed to reaching 100% of Universal Health Coverage (UHC) by 2030.

Conclusion:

The health map will make it possible to control health expenditure by allocating human and financial resources according to needs and will determine the future location of health facilities to establish equity in the offer and access to health care.

1. INTRODUCTION

Access to health care refers to the processes related to the entry of individuals and population groups into the health care delivery system [1]. It is a multi-faceted concept involving five dimensions: affordability (costs of using health care), acceptability (compliance with and satisfaction with health services), availability (adequacy of the provision of health), geographical accessibility (spatial distribution of health structures and services), and accommodation (relevance and adequacy of health services). These five dimensions show us that access to health care can be measured and integrated into the design and monitoring of a country's government policy [1].

The medical coverage of the Moroccan population has increased considerably in less than 15 years, but there is still a long way to go to achieve Universal Health Coverage (UHC) [2].

According to the main findings of the evaluation of the Medical Assistance Scheme (RAMED) carried out by the National Observatory for Human Development (ONDH) in 2017: 1) RAMED is a relevant instrument for the reduction of social inequalities in access to care. (2) The generalization of RAMED has indirectly put the public hospital service under great strain. (3) The financing of RAMED is still problematic, and (4) The targeting of RAMED, unfortunately, does not cover the poorest [3].

To assess inequity, we must look at health both from the perspective of demand and the supply of care. In other words, it is necessary to explore not only the difficulties of internalization by individuals of the requirements of good health but also the degree of coverage of the population by the existing healthcare offer.

The Moroccan Ministry of Health and Social Protection (MSPS: Ministère de la Santé et de la Protection Sociale) has adopted a multitude of strategies and interventions, which consist of acting on the Social Determinants of Health (DSS) to improve the health of the Moroccan population in general, while reducing regional disparities and health inequities (extension of medical coverage, reduction of maternal mortality and infant mortality with a focus on rural areas, etc.).

However, continued and optimal efforts are needed to: (1) further improve indicators (such as national averages) of health to catch up with other countries and (2) reduce inequities related to socio-demographic factors to improve the health of the entire Moroccan population and to ensure the well-being of all, without leaving anyone behind.

In a quantitative survey on access to care carried out between 2010 and 2011, 1200 questionnaires were distributed in three contrasting geographical zones: an urban area, a mountainous area, and an arid zone sparsely populated and far from decision centers. The results of this survey showed that more than 80% of the surveyed population said that access to care facilities is perceived as difficult to very difficult and that the quality of care is poor or inadequate. This proportion rises to more than 90% in the arid zone. The financial barrier is the main reason for 67.2% of the population waives private medical consultations. This proportion rises to 81.3% in the arid zone [4].

2. METHODOLOGY

2.1. Study Design

In this paper, we are particularly interested in non-genetic and non-biological inequalities, which are considered avoidable and unfair. As an immediate corollary to this, we can take the example of biological inequalities between men and women or between young and old, which are not considered inequities. On the other hand, the fact that a child born in a developed country like Japan can expect to live to 85 years or more while in an African country like Sierra Leone, the life expectancy is less than 55 years constitutes a flagrant inequity [5].

2.2. Data Sources

Our study aims to analyze the specific issues related to the Moroccan health policy centered on the allocation of the healthcare offer, and the efforts to improve financial accessibility, specifically by developing medical coverage.

As such, to analyze Morocco's specific situation, our methodology is based on research and data taken from official institutional publications in Morocco. The main source is the Ministry of Health and Social Protection (MSPS), which is responsible for developing and implementing government policy pertaining to national health. They are also behind the creation and implementation of The Moroccan Health Map. The second source is the National Agency for Health Insurance (ANAM) which is responsible for providing technical support for Compulsory Health Insurance (AMO) and ensuring the implementation of system regulation tools.

These national data sources and academic research on the subject provide a well-rounded view of the healthcare offered in Morocco. The specific data for this cross-sectional study were obtained from the analysis of documents such as:

- Moroccan administrative law specific to healthcare.

- Publications of certain public institutions: the Ministry of Health and Social Protection & the Agency National Insurance & Sickness.

- The content of the websites of the above public institutions.

- The Moroccan Health Map

- Relevant research on health inequities.

- An institutional analysis of the departments likely to act on a given Determinants Social Health (DSS).

- A review of the existing coordination mechanisms which are supposed to promote joint or at least concerted actions between the different actors mobilized for human development.

2.3. Data Management and Analysis

The data was analyzed with Microsoft Office Excel 2019 and summary statistics were used to estimate the ratio of inhabitants per hospital bed and inhabitant per doctor. This is a secondary study that used data extracted from existing Ministry of Health and Social Protection data. Thus, no ethical approval and no consent to participate were necessary.

3. RESULTS

3.1. The National Health System

Health equity in Morocco is well underlined by the Dahir n° 1-11-83 of July 2nd, 2011 promulgating the framework law n°34-09 relating to the health system and the supply of care (published in the Official Bulletin n°5962-19 of July 21, 2011). Indeed, Article 2 of this framework law indicates that “The health system is made up of all the institutions, resources and actions organized to achieve the fundamental health objectives based on the following principles: - The equal access to health care and services; - The solidarity & responsibility of the population, in the prevention, conservation and restoration of health; - Equity in the geographical distribution of health resources; - Intersectoral complementarity; - The adoption of the gender approach in health services. The implementation of these principles is primarily the responsibility of the State”.

The National Health System is made up of:

- A public sector comprising the structures of the Ministry of Health and Social Protection and the health service of the Royal Armed Forces,

- A private non-profit sector comprising the establishments of the National Social Security Fund (CNSS) and mutualist establishments,

- A private for-profit sector made up of clinics, medical consultation offices, radiological examination offices, medical analysis laboratories, dental surgery offices, nursing care offices, midwives, and pharmacies.

In practice, the health policy of the Moroccan government is implemented by the Ministry of Health and Social Protection, mainly through two networks: the network of primary health care establishments and the hospital network.

3.2. Coverage Indicators

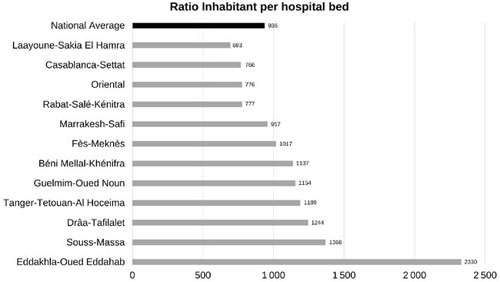

The figures given by the 2021 health map indicate that the public infrastructure includes 861 urban health centers, 2,124 rural health centers, 165 hospitals with 23,786 functional beds, 10 psychiatric hospitals with 1,374 functional beds, and 128 hemodialysis centers equipped with 2,613 dialysis machines. As for the private infrastructure, it includes 384 clinics with 12,534 beds and 234 hemodialysis centers. The national average ratio is 936 inhabitants per hospital bed. This ratio varies from 693 to 2330, which is a multiple of 2.48x the national average at its maximum. Of the 12 regions of Morocco, 8 regions have a ratio higher than the national average. Fig. (1) shows that this ratio can be expressed as an average of 10 beds per 10000 inhabitants.

Regarding human resources, especially physicians, Morocco has 27,881 physicians (public & private combined) in 2021, of which 50.9% are in the private sector and 65.2% are medical specialists.

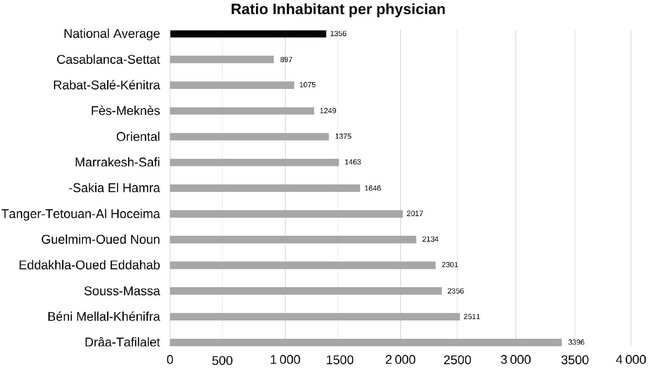

The shortage of health personnel is a major problem for the Moroccan health system. The health map set the density per 10,000 inhabitants to 7.3 for physicians (public and private). This density is very far from the critical threshold recommended by the WHO for the achievement of the SDGs, namely 17.5 doctors and 39.0 nurses per 10,000 inhabitants [6]. An inequitable distribution between the regions of Morocco exacerbates the deficit in medical personnel. This same data analyzed according to the ratio of inhabitants per physician (public and private), reveals that the regions of Rabat-Salé-Kenitra, Fes-Meknes, and Casablanca-Settat have a coverage higher than the national average, which is one physician for 1,356 inhabitants. In fact, the region of Casablanca-Settat holds the first rank with a physician for 897 inhabitants, followed in the second position by the region of Rabat-Salé-Kenitra with a physician for 1,075 inhabitants. On the other hand, the region of Beni Mellal-Khénifra and that of Drâa-Tafilalet have the lowest ratio, with a physician for 2,511 inhabitants and a physician for 3,396 inhabitants, respectively.

Regarding the distribution of public physicians in the different regions, there is a high concentration of physicians in the regions of Casablanca-Settat, Marrakesh-Safi, and Fez-Meknes. These three regions count 7,857 public physicians, representing 57.4% of all physicians.

As presented in Fig. (2), the data taken from the Health Map show us that in Morocco, the supply of health care is weak at the level of health facilities, that the human resources are not sufficient and that there is a great disparity between the twelve regions of the country.

3.3. Reasons for not Seeking Health Care

The decision to use a healthcare worker is made in most cases when symptoms persist, especially for patients away from health centers. The decision to use a physician is made collectively; generational hierarchy, gender relations, and economic dependency relationships are key factors [4].

The constraints to accessing the health center are often important. They range from transportation costs, difficulties in finding a vehicle in isolated areas (sometimes including urban areas), expenses related to housing and meals with accompanying persons, and specific expenses associated with medical care (laboratory tests, medications, etc.) [4].

Once the decision has been made and the route is taken, patients often face new barriers at the reception of the healthcare facility that may increase the length of care. For instance, baksheesh and/or intervention of interconnections constitute the factors favoring access to the provider. The objective displayed by the patients is to reach the physician, and preferably, the medical specialist; the unavailability or absence of the physician is quickly perceived as a failure in the face of all the efforts made to access care [4].

The interactions with the physician will be all the more facilitated and appreciated if he speaks the patient's language, understands his daily practices, and knows his living conditions and the pathologies of his context; the physician who hails from the region where he practices is then presented as the ideal practitioner. The specialist physician practicing in large cities) and his own region is also particularly sought after [4].

3.4. Sources of Health Care Expenditures in Morocco

Health financing in Morocco is characterized by a multiplicity of funding actors. These consist of public sources through state tax revenues, health insurance contributions (including various forms of private insurance), and private sources through direct household payments. The ratio of direct household expenditure relative to the Total Health Expenditure (THE) indicates the level of financial protection a country provides to its people. One of the objectives of Universal Health Coverage (UHC) is to reduce this ratio to less than 25%. The goal is to ensure that collective health financing is based on national solidarity and ensure a maximized pooling of health risks.

| Funding Sources | 103 USD** | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Contribution to the AMO | Households | 861 731.5 | 14.1% |

| Public Enterprises and institutions | 40 825.6 | 0.7% | |

| State | 203 341.8 | 3.3% | |

| Private enterprises | 665 642.3 | 10.9% | |

| Territorial Communities | 25 364.7 | 0.4% | |

| Subtotal | 1 796 905.9 | 29.5% | |

| Direct contributions to health services (excluding AMO) | Households | 2 777 133.4 | 45.6% |

| State (Budget) | 1 356 007.2 | 22.3% | |

| Territorial Communities | 95 423.0 | 1.6% | |

| Employers | 23 692.6 | 0.4% | |

| International Cooperation | 13 155.9 | 0.2% | |

| Other (ONGs,…) | 30 434.7 | 0.5% | |

| Subtotal | 4 295 846.8 | 70.5% | |

| Total | 6 092 752.7 | 100% | |

**Estimated costs after conversion of the Moroccan Dirham (MAD) into USD with an exchange rate of 1 USD =10 MAD.

AMO: Assurance Maladie Obligatoire (Compulsory Health Insurance)

Since 1997, we note that several efforts have been made to improve health financing in Morocco.

In 2018, the direct household expenditure constituted 45.6% of THE versus 50.7% in 2013. Thus, the drop of around 5% constitutes a positive element for the health financing system in Morocco [7, 8]. In addition, the country's contribution to health financing remains almost unchanged at 24% in comparison to that of 2013. The share of health insurance in the financing of health expenditure is 29.3%, which is an increase of 6.9 points compared to that of 2013. The respective contribution shares of public enterprises and institutions and international cooperation are 0.4% and 0.2% [7, 8].

It should be noted that collective and solidarity/mutual financing reached 53.3% in 2018 versus 46.8% in 2013. The improvement of solidarity financing constitutes a positive trend toward financial protection of the population and especially the most vulnerable segments.

The evolution of health financing should in principle, tend towards an increase in the share of health insurance for more solidarity and risk pooling. In 2018, Morocco spent 60.9 billion dirhams on health, an increase of 8.9 billion MAD since 2013. Taking into account an exchange rate of 1 USD for 10 Moroccan Dirhams (MAD), this represents a little more than 6.76 billion USD; which represents 5.5% of GDP compared to 5.8% in 2013. The average annual expenditure per inhabitant is 186.3 USD [7, 8].

Household participation in health expenditure is estimated at 2.78 billion Dollars in the form of direct expenditure in 2018, which represents 45.6% of THE. When we add to the direct contribution of households the contributions to health insurance, which they make on an annual basis, this percentage rises to 59.7% of the THE [7, 8].

The breakdown of funding sources for health costs is given in Table 1.

Analysis of the sources of financing shows that households remain the main financiers of health, with 27.8 billion dirhams as direct payment (OOP: Out of Pocket) and 8.6 billion in the form of contributions to health insurance.

From 2013 to 2018, the share of the country's health financing stagnated at around 25%, while that of households fell from 63.1% to 59.7%. The share of Private Enterprises. is 1.1%, thus registering a decrease of 3% compared to that of 2013. This reduction is explained by the evolution of the share of health insurance, which has evolved to reach 29.3% of the DTS in 2018 [7, 8].

In value, direct household expenditure increased from 1.75 billion dollars in 2006 to 2.78 billion dollars in 2018. Relative to the population size, direct household expenditure per capita fell slightly between 2010 and 2018 (USD80.2 per inhabitant in 2010 versus 78.9 USD per inhabitant in 2018), while it was USD57.4 per inhabitant in 2006. In addition, we note that the financial protection provided by medical coverage (AMO, RAMED, internal and mutual funds, and private insurance companies) substantially reduces direct payments by households. Since 2006, the share of direct payments by households has continued to fall, falling from 57.3% in 2006 to 53.6% in 2010 and 50.7% in 2013 [7, 8].

The implementation of the code of the CMB has made it possible to increase the level of funding of the health system in significant proportions and to promote its collective and solidarity financing. Moreover, it is not only a question of the solvency of demand and reconsidering the field of solidarity but also of strengthening the effectiveness of the entire national health system and in particular its public component. Indeed, the establishment of the AMO and the RAMED made it possible to improve the financial situation of the establishments of health care, in particular the public hospitals, which represent 80% of the bed capacity of the country.

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. Supply, Availability, and Quality of Care

Regarding access to care, the analysis shows that none of the indicators point to a clear priority for action. However, more equitable access to health care could be obtained mainly by reducing regional disparity. The lack of financial means as a reason for not seeking care, as an indicator, seems to show a moderate degree of inequity. The well-being score, urban environment, and high school level or higher are the socioeconomic factors that contribute the most to the inequities exhibited by the indicators related to access to care.

Under the principle of availability, the provision of care must be distributed throughout the national territory in a balanced and equitable manner. Public and private sector institutions, whether for-profit or not, need to be synergistically organized to respond effectively to health needs through complementary, integrated, and coordinated healthcare services.

In Morocco, there is a great lack of availability of care services that lies in the configuration of its offer. In addition, the malfunctioning of healthcare facilities makes it difficult to implement equitable funding. They also complicate the development and application of medical supervision to ensure the quality of care [9, 10].

Inequity in the allocation of financial resources manifests itself at several levels and mainly affects the use of care services.

The supply of care contributes to producing a growing demand for health. From this demand emerged a system with actors with rights and responsibilities. In fact, medicine, medical procedures, and other care services have a social cost and a price that are both defined in a healthcare market funded by several stakeholders [11, 12].

From an economic perspective, it will be the role of the state to control the cost of public health so that it is covered by public health expenditures while applying the principles of the right to health [13].

The organization of the care supply obeys several rules throughout its process of integration into the health care system. In Morocco, to respect the principles of Article 2 of Framework Law N° 34-09 [14], the provision of care must be spread throughout the national territory in a balanced and equitable manner. However, this is a challenge because even with the significant growth in supply and distribution, it remains unbalanced in terms of infrastructure [15, 16].

The four main objectives of the provision of care are (i) To anticipate and bring about the necessary evolutions of the supply of care (public and private); (ii) optimally satisfy the health care and services needs of the population; (iii) Achieving harmony and equity in the spatial distribution of material and human resources; and (iv) Correcting regional and intra-regional imbalances and managing supply growth.

The supply of care is established according to three criteria: (i) the types of infrastructure and sanitary facilities; (ii) the norms and the modalities of their territorial implantation; and (iii) the basis of the global analysis of existing healthcare provision, geo-demographic and epidemiological data, and medical technological progress [14].

The supply of care is defined, therefore, according to a process that aims at ensuring the full employment of human resources and health infrastructures to satisfy the needs of the population. At this level, the care system integrates several actors, each of which participates through its unique and indispensable role.

The itineraries, the difficulties experienced and the perceptions of quality of care make it possible to identify the multiple constraints that influence the decisions of the population to resort to a healthcare provider.

The Health Map developed by the Ministry of Health and Social Protection was used as the main tool to examine the distribution and availability of healthcare, information on financing, and the use of budgetary and human resources [17].

4.2. Basic Medical Coverage in Morocco

The development of Basic Medical Coverage (CMB) was a key step in realizing the principle of the right to health for all and the involvement of various stakeholders in the improvement of the healthcare system. The CMB was established by Law N° 65-00 published in 2002 and entered into force on August 18, 2005, by decree of application [9, 10, 18].

Law N° 65-00 on Basic Health Insurance Code introduced Compulsory Health Insurance (AMO) and the Medical Assistance Scheme (Régime d’Assistance Médicale; RAMED). The AMO is based on the principles and techniques of social insurance for the benefit of persons in remunerative employment, pensioners, former resistance fighters and members of the Liberation Army, and students. In addition, RAMED is based on the principles of social assistance and national solidarity for the benefit of the poor. This code is the foundation of social protection in health [18].

The purpose of setting up RAMED is to provide poor populations not covered by Compulsory Health Insurance with access to quality health services. RAMED seeks to address the need for equity and social justice in access to health care while reducing the stigma and barriers associated with the former system of exemption from payment based on the neediness (“poverty”) certificate issued by the local administrative authorities.

RAMED medical coverage contributes to the explanation of the inequities induced by the access to places of consultation. But it should be noted in this case that people with general medical coverage consult more than those without it.

4.3. Covered Populations and Access to Care

Above all, it is necessary to recall that social inequalities, health inequity, and territorial disparities in Morocco constitute a persistent phenomenon recognized at the highest level of the State. Indeed, several Royal speeches have drawn attention to this bane which hinders the development of the country, in particular the Royal speech of August 20, 2019, in which the King of Morocco set up the special commission on the development model (CSMD), which published its general report in May 2021 and in which it is pointed out, among other things, that in terms of citizen impact, “All citizens, regardless of their socio-professional status and their place of residence, are equal in front of health, with access to protective health coverage and a quality care offer” [19].

To achieve coverage for 90% of the population, in 2017 the legal and regulatory framework for medical coverage of professionals, self-employed workers, and self-employed persons was promulgated.

In 2005, the rate of medical coverage of the population of Morocco; all medical coverage plans combined, was 16%.

In 2019, this rate reached 70% (AMO: 30%, RAMED: 30%, special schemes: 5%, categories benefiting from article 14 of law 65-00: 4% and students: 1%) [2].

In April 2021, his Majesty King Mohammed VI kicked off the project to extend social protection to all Moroccans with the generalization of Mandatory Health Insurance (AMO) before the end of 2022.

According to the national barometer on access to care and medical follow-up of the insured persons of the National Fund of Social Welfare Organizations (CNOPS) and the National Social Security Fund (CNSS), carried out between the end of 2010 and the beginning of 2011, the use of AMO beneficiaries' care has been characterized by situations of dissatisfaction which must be corrected [20]. First, the complexity of the administrative procedures for opening rights to health insurance or agreements for organizations managing the treatment in third-party payment mode, in addition to the list of reimbursable medicines which is considered limited by the insured. Adding to that, the delay of reimbursement of sickness records was judged by 52% of dissatisfied insureds as too long [20]. In other words, the intervention process regarding the rights of the insured and meeting the needs expressed by the beneficiaries of the AMO remains long and provokes conflicts.

On the other hand, more than half of the insured through AMO state that accesses to care in general is satisfactory, with good coverage of expensive care (Chronic Disease, Hospitalization, and Surgery), and with a quality reception at the counter and information of the rights and benefits is provided [20].

For poor people, the management framework suffers from bureaucracy, non-standardization, and the subjectivity of RAMED's eligibility criteria. Although the price of consultations in public facilities is the lowest on the market, it did not significantly improve RAMEDists' access to care [9, 10].

CONCLUSION

Since the organization of the first national health conference in 1959, Morocco has had a National Health System (SNS) capable of responding to international challenges.

It should be remembered that the use of care is based on two essential principles, namely equity and equality in access to care.

The portion of a patient's direct payments has a serious health impact because people who cannot pay for care are discouraged from seeking care. As a result, they do not receive early treatment despite a much higher healing potential. Therefore, the Moroccan government is seeking to promote health insurance through AMO and RAMED due to its ability to reduce the burden of household spending on health.

The move towards universal health coverage faces challenges such as:

1. Extending coverage to populations not covered, including the liberal sector and the self-employed.

2. The reduction of direct household expenditure (OOP: Out of Pocket) and the financial protection of the population against catastrophic expenditure

3. The request for increased funding and its sustainability

4. The equitable availability of essential services and the quality of these services

However, continued, and optimal efforts are needed to: (1) further improve indicators (such as national averages) of health to catch up with other countries and (2) reduce inequities related to socio-demographic factors to improve the health of the entire Moroccan population and to ensure the well-being of all, without leaving anyone behind.

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS

This paper relies heavily on the Health Map developed by the Ministry of Health and Social Protection in 2016. It is a quite powerful reporting tool that makes the data used in this paper very reliable as they are officially sanctioned data, and it is made available to the wider public. This is however also the limitation of this paper. If there are any internal data discrepancies, however unlikely, within the Ministry’s dataset; then it would impact the reliability of our findings. To account for this possibility, future studies can focus on a randomized verification study to validate the data.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| For some abbreviations | = We have adopted in the manuscript the French abbreviations commonly used in Morocco. |

| AMO | = Health Insurance Compulsory (Assurance Maladie Obligatoire) |

| ANAM | = Agency National Insurance & Sickness (Agence Nationale de l'Assurance Maladie) |

| CMB | = Basic Medical Coverage (Couverture Médicale de Base) |

| CNOPS | = National Fund of Social Welfare organizations (Caisse Nationale Des Organismes De Prévoyance Sociale) |

| CNSS | = National Social Security Fund (Caisse Nationale de Sécurité Sociale) |

| DSS | = Determinants Social Health (Déterminant Social de santé) |

| GDP | = Gross Domestic Product |

| MAD | = Moroccan Dirham (code of the official monetary currency of Morocco) |

| MSPS | = Ministry of Health and Social Protection (Ministère de la Santé et de la Protection Sociale) |

| ONDH | = National Development Observatory Human (Observatoire National du Développement Humain) |

| OOP | = Out of Pocket |

| RAMED | = Assistance Scheme Medical (Régime d'Assistance Médicale) |

| SDGs | = Sustainable Development Goals |

| SNS | = National Health System (Système National de Santé) |

| THE | = Total Health Expenditure |

| UHC | = Universal Health Coverage |

| UN | = United Nations |

| USD | = US dollar |

| WHO | = World Health Organization. |

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

Not applicable.

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

Not applicable.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

All data reported in the manuscript are from published and referenced articles and reports.

FUNDING

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.