All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Challenges of Conducting a Critical Ethnographic Breastfeeding Study in the Post-Disaster Settings: Lessons Learned

Abstract

Post-disaster settings are the most vulnerable settings where researchers may face challenges specific to their safety, research logistics, and maintenance of ethical integrity in a high-stress context. This paper presents the researcher’s reflections on undertaking a critical ethnographic breastfeeding study in the post-disaster settings of rural Pakistan, where displaced women with young children were under extreme stress due to recurrent natural disasters, displacement, disruption to life, and homelessness. This paper identifies encountered challenges by the researcher during fieldwork in that post-disaster settings, presents the strategies utilized during the fieldwork, and shares recommendations for future researchers on maintaining research integrity in this challenging context.

1. INTRODUCTION

Displaced families are forced to flee their homes and resettle in post-disaster settings during natural disasters. Pakistan is one of the lower-middle-income South Asian countries that are susceptible to natural disasters, such as earthquakes, hurricanes, drought, heat waves, and floods bought by monsoon rains each year between July and September [1]. Since 2010, Pakistan has experienced more frequent and intense natural disasters linked largely to global climate change [1]. These disasters not only damaged roads, houses, livestock, crops, telecommunication systems, and the infrastructure of various social institutions (including healthcare settings) [2] but also resulted in increased child mortality and morbidity rates [3]. Pakistan has the second-highest younger-than-five-years child mortality rate (86 per 1000 live births) in South Asia due to suboptimal breastfeeding practices and malnutrition [4-6]. During disasters, affected communities and families are temporarily resettled in post-disaster settings (disaster relief camps) established by the government and non-governmental-based humanitarian relief agencies. In post-disaster settings, child mortality often increases by approximately 10% because of a further decline in breastfeeding prevalence, subsequent rise in childhood malnutrition, and outbreaks of contagious and infectious diseases such as diarrhea and dysentery [3, 7-9]. A limited number of studies in Pakistan focus on the breastfeeding experiences of internally displaced mothers and the way forward to support their breastfeeding practices in post-disaster settings. To overcome this knowledge gap, a critical ethnographic study was undertaken in rural Pakistan's post-disaster settings where the displaced population was under extreme stress due to recurrent natural disasters, displacement, disruption to life, and homelessness. Before the commencement of the fieldwork, the researcher sought ethical approval from the University of Alberta Research Ethics Board and relief agency working actively in the post-disaster settings in Pakistan. The researcher’s experiences in that post-disaster setting raised questions about personal safety, logistics challenges, and maintaining ethical integrity in a high-stress context. This paper identifies encountered challenges by the researcher during fieldwork in that post-disaster settings, presents the strategies utilized during the fieldwork, and shares recommendations for future researchers on maintaining research integrity in this challenging context. Note that this paper will not discuss details of the study method or research findings.

1.1. Background of the Post-disaster setting

Being a critical ethnographer, I undertook my fieldwork in Chitral, situated in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province of Pakistan with an approximate population of over 479,000 people [10]. Chitral is a mountainous region located in the extreme north of Pakistan (lies at an average elevation of 1500 meters above sea level). The altitude of the mountains in Chitral ranges from a minimum of 4000 feet to over 20,000 feet [11]. This region shares borders with Afghanistan on its north, south, and west border and China on its north and northeast border [10]. This region has many snowy peaks, green valleys, glaciers, rivers, and lakes. Chitral has warm summers (ranging between 25 to 40°C) and cold winters (below-freezing temperatures ranging between -7 to -15°C). During the past few years, this region has had heavy snowfall ranging from two feet (in general) to up to 70 feet, mainly at higher elevations [10]. There are approximately 100 small villages in the mountainous region of Chitral, with an average population ranging from 2000 to 5000 people in each village [11]. Although Urdu is the national language of Pakistan and is understood and spoken by many people in Chitral, the commonly spoken local language is Khowar. Due to ethnic diversity, various other local languages are spoken in this region. Chitral's predominant religious groups include Sunni Muslims, Ismaili, and Kalash [11]. In many sub-cultures of Chitral, women are required to observe the strict veil (pardah) and do not have mobility rights unless they have permission from the male members or household heads or unless any male member accompanies them [10].

During the past decade, this region has experienced a sudden drop in tourism due to political instability at the Afghan border, tribal disputes (concerning land, forestry, and water), and recurrent natural disasters (mainly earthquakes, landslides, glacial lake outburst flooding, and flash flooding). The region has many villages in the mountainous region of Chitral that are underserved due to the isolated nature of their geographic location, political instability, tribal disputes, or inaccessibility during humanitarian emergencies.

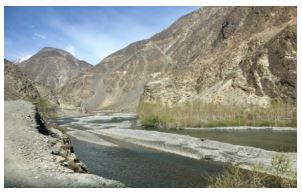

Many villages in Chitral are remote and have non-availability of basic facilities, such as clean drinking water, health care units, schools, proper roads, public transportation, electricity, sanitation facilities, and waste disposal systems [10]. The recurrent disasters in this region resulted in many families living in temporary settlements, where people are housed in tents, transitional shelters allocated by the disaster relief agency, or makeshift huts built out of mud and brick (locally known as katcha houses). In 2015, thousands of families in Chitral were affected by the Glacial Lake Outburst Flooding and subsequent earthquake. The glacial outburst flooding and subsequent earthquake have accumulated a large number of debris on the residential and agricultural land of the affected villages. Many of the disaster relief camps (mainly shelters and tents) are placed at the top of the hill and mountain, mainly due to the unavailability of residential land, the immovable nature of the debris, the unavailability of manpower to move the debris from the residential land, and to prevent the possibility of the drowning of the affected families in the case of a subsequent glacial lake outburst flooding.

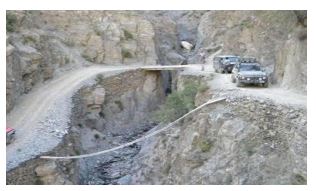

Refer to Figs. (1 and 2), showing the accumulated hard-to-move debris on the residential and agricultural land and the location of angle iron green transitional shelters at the top of the hill, respectively.

1.2. Encountered Challenges During Fieldwork

Before entering the field, based on the mass media’s presentation of the post-disaster settings in Pakistan, I assumed that the displaced people would be living in a single geographic location in tents allocated by the disaster relief agency where there are privacy and availability of healthcare/social services. However, on entering the field, I came to know that displaced families are residing in a variety of temporary housing, mainly transitional shelters, tents, or mud-brick-based houses at higher altitude places (top of the hills) to prevent drowning during flooding. Moreover, in view of the media’s portrayal of services made available to the disaster-affected communities in Pakistan, I assumed displaced families would have been receiving continued humanitarian aid and healthcare/social services. However, my fieldwork uncovered a different reality about inequality surrounding the distribution of humanitarian aid and shed light on the false presentation of services made available in post-disaster settings. The encountered challenges by me during fieldwork in the post-disaster settings were specific to safety, ethics, and logistics, mainly due to the unpredictable nature of the environmental risks, cultural diversity and language differences, and limited privacy during in-depth interviews with breastfeeding mothers. Each of these challenges is discussed below.

1.3. Safety

I undertook my fieldwork in the four different disaster-affected villages of Lower Chitral, including Shali, Bumburate (Kalash valley), Zhitoor (Garam Chashma valley), and Beshqair (Garam Chashma valley). Each of these villages was located far from each other and travelling to these villages required approximately 1.5 to 2.5 hours of one-way travel from Chitral city. During the fieldwork of this critical ethnographic research, there were various unexpected scenarios and environmental risks, including unstable roads in the mountainous region, landslides during my road travel to villages having a disaster-affected community, extended hours of travel i.e. four to six hours per day through an unstable mountainous region, recurrent earthquake tremors of more than five on the Richter scale, placement of disaster relief camps far from cities (on top of the hills), risks of massive destruction of roads and/or airport in the case of aftershocks, and non-availability of health care services in case of injury or sickness. Figs. (3 and 4) depict unstable roads in the mountainous region of Chitral, Pakistan.

In ethnographic research, a researcher is expected to immerse into the culture for a prolonged period fully. However, in view of the active disaster in the region, the risk of political instability, and the non-availability of safe accommodation (hotel or motel) in the villages (field sites where disaster relief camps were located), I had to limit my stay in the field to seven to eight hours per day and travel back to Chitral city to a safe location (hotel). Moreover, in view of the environmental risks, after gathering sufficient data from in-depth interviews and field observations in the lower Chitral, I left the field site and moved to a safer city. Prioritizing and caring for my safety, I could not collect data from villages in the upper Chitral that were also severely affected by recurrent natural disasters. I captured these experiences in my journal:

"The road travel on unstable mountainous roads was scary. Land sliding was actively happening on those mountainous roads. There were no hospitals or healthcare settings around. There were many army check posts on the way. I had to show my national identification card to prove my identity and share the purpose of my visit at each check post. The army officers kept my national identification card with them as collateral. They shared that I would be directly responsible in case any act of terrorism happens in that region during my visit. I had no choice but to keep my identification card with them. I finally reached a place where a temporary shelter was located at the top of the mountain. I learned that besides natural disasters, this area often becomes politically unstable as it is situated near an Afghan-Pakistan border. I climbed the mountain for around 10 minutes and finally reached a shelter. During the in-depth interview with the mother, all of a sudden, earthquake and sandstorms started. The shelter started to shake badly. Young children, older people in the shelter and cattle started to panic to find a safer spot in the shelter. The sandstorm made it difficult to see anything in the surrounding. The earthquake made me dizzy and I felt the shelter would fall from the mountain and no one would survive. During that time, I heard yells, cries and recitation of religious verses in the household. After a few seconds, when the earthquake tremors stopped, I found that there was no major physical damage. However, the psychological impact of this event is still in my mind. The community mobilizer [representative of the relief agency] who accompanied me as an interpreter suggested we should leave this place as the post-earthquake event could happen anytime and be more dangerous than this one. Being an outsider, I had the option to leave this place and move to a safer site. I felt bad that unfortunately, leaving this place is not an option for the families residing in those disaster-affected areas, which call this place their homeland. (Research journal; Hirani, 2018)".

1.4. Ethics

Irrespective of if an ethnographer is an outsider or insider, common ethical challenges critical researchers may encounter are related to positionality, power, and knowledge construction, especially if there is any difference in race, color, gender, social class, culture, or status of the researcher and participants [12-14]. I approached this critical ethnographic study as a partial insider. I was an insider to this research because I am a Pakistani female proficient in the national language (Urdu). I am a mother, nurse, and lactation consultant with prior experience conducting research in Pakistan's low-income, rural and semi-urban settings, particularly with vulnerable women. However, simultaneously I approached this research as an outsider because I was born, raised, and lived in an urban city in Pakistan. I am an educated Muslim female from an upper-middle-class family, pursuing my PhD in nursing during my fieldwork, and living in Canada for two years before data collection. I have no prior personal experience of being internally displaced and managing to breastfeed while residing in a disaster relief camp. The sub-culture, socio-economic class, provincial language, and religion of many of the participants were different from mine. Being a partial outsider, I could not fully understand the local language (Khowar) and other local languages. In the initial phase of my fieldwork, I felt that these differences were directly/indirectly affecting my direct communication with the gatekeepers, community people and participants speaking local languages. I was worried that these differences may affect my rapport building with the community/participants and my ability to understand participants’ perspectives (worldviews) fully. I captured these feelings in my journal:

"During my fieldwork, I wished that I could talk to all my participants in their local language. This would have helped me to build trust, sense their emotions, know them better, and know all their cultural norms to understand their worldview better. Although many things were common between us, still many things were different. (Research journal; Hirani, 2018)"

1.5. Logistics

In the post-disaster setting, it was challenging to find a noise-free setting for the in-depth interviews as many people around and mothers lived in overcrowded temporary housing (shelters and tents). Interviews were conducted at the shelters allotted to the disaster-affected community. Although I was assigned a corner of a shelter where in-depth interviews were undertaken, it was challenging to stop the movement of uninvited people (family members, neighbours, relatives, children, and friends) entering the shelter without seeking permission. In Chitral, women highly valued privacy while breastfeeding their babies, preferred covering their bodies with long scarves (dupatta) and considered breastfeeding a private matter, hence avoiding talking about it in public or in front of their family members. Due to a lack of privacy, many participants felt shy and hesitant to share their ‘breastfeeding experiences’ during the in-depth interviews. The recorded observation in my journal is as follows:

"The shelter (temporary housing) was too small for a family of 10-12 people, including a breastfeeding mother, her husband, three to five children, and her in-laws i.e., mother-in-law, father-in-law, sisters-in-law, brothers-in-law. I observed that in those overcrowded shelters, mothers preferred covering themselves and were hesitant to breastfeed in front of family members, relatives or neighbours. During the interview, out of shyness, many mothers either changed the topic as soon as any family member entered the shelter. During interviews, many of these participants initially responded to my questions in short sentences without mentioning any details and a few were covering their mouths with their scarfs out of shyness after providing a brief answer to my questions. It was a great struggle to interview mothers when people were around. (Research journal; Hirani, 2018)."

1.6. Strategies Utilized to Overcome Challenges during Fieldwork in Post-Disaster Setting

As a critical ethnographer, I adapted a variety of strategies during my fieldwork in Chitral. Those strategies included the demonstration of a reflective approach, critical consciousness, cultural immersion, mindfulness of positionality, trust-building strategies, and practical wisdom. Each of these strategies is discussed below.

1.7. Reflective Approach

A critical ethnographer plays a significant role in assuring that the research process proves mutually beneficial for the researchers and participants [15]. Throughout the research process, a critical ethnographer assumes an ethical responsibility and adopts a reflective approach to studying sources of domination while engaging with the participants [15]. In view of this approach, during the conduct of this critical ethnographic study, I practiced self-reflexivity throughout the fieldwork by reflecting on and writing down my self-perceptions, beliefs, feelings, and actions that may create a barrier in the process of communication. To overcome the challenges surrounding power differences and logistics, I maintained a trusting relationship with the disaster-affected community, demonstrated cultural sensitivity, informed participants about all aspects of the study, maintained their confidentiality throughout the research process, valued their preference in choosing a venue for the in-depth interviews, and involved participants in the iterative process of data collection and analysis.

1.8. Critical Consciousness

Critical ethnographers often hold power and positionality differences from the participants, demonstrating critical consciousness is an essential ethical consideration during the research process [16]. Critical consciousness aims to respect the autonomy of study participants, assure reciprocity in the research process, maintain transparency while handling any ethical challenges, and assure methodological and ethical rigor of the undertaken research [16]. Moreover, a critically conscious researcher maintains transparency in the research process and is involved in self-reflexivity, enabling them to present research findings that are reflective of reality and the participants' voices [16, 17]. During all phases of this critical ethnographic study, I critically assessed and analyzed ethical challenges affecting the study participants' lives. During this study, I was involved in self-introspection by maintaining a journal. For instance, during my fieldwork, I refrained from judging mothers who were not continuing breastfeeding or were using formula milk despite their ability to sustain their breastfeeding practices. Instead, I used these situations as an opportunity to uncover barriers that negatively affect the maternal agency and result in the discontinuation of breastfeeding practices.

1.9. Practical Wisdom (Phronesis)

Phronesis involves intellectual engagement with the participants and research context and demonstrates a critical understanding of the moral and ethical implications of decisions [18, 19]. As ethnographers often encounter unexpected ethical dilemmas or situations requiring them to undertake ethical decisions, phronesis facilitates an ethnographer to demonstrate awareness of their values and to trust self-intuition about the implications of a decision in immediate and future situations [19, 20]. Phronesis facilitated my ability to ensure my safety during the fieldwork. I consulted key stakeholders of the relief agency to identify villages in Chitral, checked weather conditions, and looked into the condition of roads before travelling from Chitral city to the villages located in the remote areas of Chitral. As advised by the relief agency's key stakeholders, considering the region's unstable political situations (rise in homelessness, armed conflict and disputes based on nationality) and the possible threat to my safety, I refrained from disclosing that I am currently residing in Canada. At all times, I communicated in the national language of Pakistan. I also always carried my Pakistani national identification card to prove my status as a Pakistani citizen when entering villages having security check posts managed by the Pakistani army and Chitral scouts. These interventions facilitated me in meeting security requirements and in gaining access to the villages. I also used practical wisdom (phronesis) to make methodological decisions about the sample size, manage the resources and time during the fieldwork, undertake field observations, and modify the interview guide as the fieldwork unfolded.

1.10. Cultural Immersion

In critical ethnography, cultural immersion brings new insight into the phenomenon of interest and facilitates the ethnographer to critically examine the social structures that contribute to oppression, inequality, and domination [21]. During the research process, the researcher immerses into the culture through fieldwork and an iterative process of data collection and analysis [22]. Data gathered through this process is neither objective nor subjective but “intersubjective” in nature because it represents a mutual effort of the researcher and the study participants within a particular cultural context [23]. Cultural immersion begins with the process of gaining, building, and maintaining a trusting relationship with the key stakeholders and the target group [24]. Being a partial outsider, I learned about the participants’ culture, practiced their ways of meeting and greeting, demonstrated respect for their cultural norms and practices, demonstrated a non-judgmental attitude, and adapted their ways of dressing. I valued participants’ opinions, respected their worldviews and preferences, and sought their views on the phenomenon of interest, considering them as experts and equal partners in meaning-making from the gathered data. Cultural immersion facilitated me in negotiating the power and positionality differences and overcoming possible challenges in the conduct of this research. It also facilitated me in the process of building and maintaining a trusting relationship with the gatekeepers, stakeholders, and participants and producing trustworthy findings in collaboration with the internally displaced mothers facing breastfeeding barriers.

1.11. Mindfulness of Positionality and Assumptions

During my fieldwork, upon encountering a different reality than anticipated, I decided to remain mindful of my positionality and assumptions. Mindfulness of my positionality and assumptions as a partial insider and partial outsider allowed me to embrace new knowledge, perspectives, and diverse aspects of the culture during data collection. To uncover the reality without imposing my assumptions, during my fieldwork, I remained mindful of my assumptions, practiced reflexivity through journaling, used more than one data collection method to validate the truths, and continuously asked for clarification from the participants and other stakeholders. These efforts were also instrumental in overcoming the power and positionality differences and most importantly, my personal biases being a nurse and lactation consultant. My positionality as a Pakistani female who knows the Pakistani culture and communicates in the national language of Pakistan (Urdu), as well as the involvement of a local female Chitral community mobilizer who has a sound understanding of local languages and context, facilitated and navigated the challenges related to language comprehension and cultural interpretation during the fieldwork. Moreover, during the fieldwork, this collaboration facilitated access to a variety of information, such as the background of the shelter program, facilities available in the community, the region's political context, and the community's cultural norms. It also supported validating the data gathered through field observation and in-depth interviews with participants.

1.12. Trust-building Strategies

During my fieldwork, I followed Kauffman’s five phases [24] as a strategy to build trusting relationships and negotiate the power differences between the participants and myself. The phases included: impressing, behaving, swapping, belonging, and chillin’ out [24].

1.13. Impressing

During the initial phase of “impressing”, the researcher spends a few weeks in the field to gain insight into the cultural context of the participants and the characteristics of the myths and then practices the research topic. Being a critical ethnographer, before entering the field, I first learned about the Chitrali culture, ways of behaving, and customs through available resources on the mass media. Moreover, I established connections with the key stakeholders of the humanitarian relief agency and reviewed available documents on their website to gain knowledge about the context. At the beginning stage of my fieldwork, I adopted the customs (ways of meeting and greeting), followed the community’s way of dressing, and established rapport with the healthcare team in the setting of disaster relief camps. I maintained a trusting relationship with the community mobilizer who accompanied me to different villages during my fieldwork in Chitral and guided me on a specific way of behaving. I followed etiquette practiced locally (for example, saying Asalam-o-alikum, which means ‘may peace and integrity be upon you’) and wore the traditional dress of Pakistan i.e., Shalwar kameez, to earn respect and approval of the community.

1.14. Behaving

During the second phase, “behaving”, I undertook field observations and noted the layout of temporary housing (shelters and tents) provided to disaster-affected families by the relief agencies. During this phase, I continuously evaluated my actions while undertaking field observations and interacting with the gatekeepers, stakeholders (healthcare team and members of the humanitarian relief agency) and participants. While strengthening my rapport with the community, I ensured that my social class did not serve as a barrier during formal and informal interactions with the participants in the identified setting.

1.15. Swapping

During the third phrase, “swapping”, I engaged in meaningful dialogues and discussions with the participants through one-to-one in-depth interviews while using a semi-structured interview guide. During all my initial interactions with the participants, I ensured I sat at their level (mainly on the floor); introduced myself; asked for their consent before interviewing them; maintained the flow of communication at their pace; and allowed them to talk more, ask questions, or seek clarifications. I was mindful to identify any sign of emotional distress during the in-depth interview. I maintained field notes and reflexive journals throughout this phase.

1.16. Belonging

The fourth phase is “belonging,” during which I built rapport and trusting relationships with the participants, facilitating them to talk and discuss challenges associated with their breastfeeding practices without hesitation or shyness. As a gesture of hospitality, I was offered tea and asked to join the family for their lunch meal, during which I got an opportunity to have informal conversations with the family members of the displaced mothers, including mothers-in-law, fathers-in-law, sisters-in-law, and elder children. These informal interactions enabled me to explore challenges encountered by the family to place a tent or get transitional shelter; identify family routines and dynamics; note the quality, quantity, and type of food available to the family during lunch time; explore the responsibilities of women within the household; observe the nature of social ties that the family members and neighbors were maintaining, and observe the type of childcare support offered to the displaced mothers by their family members and neighbors.

1.17. Chillin’ Out

The fifth phase is “chillin’ out” during which the researcher and participants gain a deeper understanding and acceptance of each other [24]. At that time, I reflected on various aspects of my fieldwork. Due to accessibility issues, political instability, and recurrent disasters happening in the region, I could not stay in each of the villages for an extended period and had to end my fieldwork sooner. Although I had the option to exit from the region as an outsider, the displaced mothers and their family members had no such choice. They still had to live in that region as it was their hometown and were hopeful that something good would happen soon. At the time of my exit from the field, I thanked all my study participants and discussed analyzed findings with the stakeholders as a way forward to improve breastfeeding support in that region. I acknowledged the contributions of all the stakeholders, members of relief agencies and health services which are risking their lives each day to offer services in challenging circumstances and are committed to improving the quality of life of many displaced families in the mountainous region of Chitral.

CONCLUSION

Conducting research in the post-disaster setting encompasses several challenges for the researchers. Encountered fieldwork challenges in the post-disaster settings of a low-middle-income country included issues surrounding the researcher’s safety, ethics, and logistics.

Although some of these challenges were anticipated during the conception phase of this study, the actual fieldwork was riskier than anticipated due to the complex and unpredictable nature of the post-disaster setting, mainly due to aftershocks in the mountainous region, political unrest in the region after a sudden rise in homelessness, displaced communities having diverse cultural backgrounds, and remote nature of the setting having inadequate public facilities (healthcare, roads, washrooms, public transportation and safe place to stay). In post-disaster settings, the use of a reflective approach (self-reflexivity), critical consciousness, practical wisdom, cultural immersion, mindfulness of positionality, and trust-building strategies are recommended during each phase of the study.

Researchers who engage in global health initiatives on disaster relief must critically analyze and attend to safety, ethics, and logistics challenges throughout the research process. Before entering into the field, it is imperative that researchers critically analyze their assumptions and avoid over-relying on information shared on mass media. Future researchers planning to undertake ethnographic studies in post-disaster settings must involve the local community members of the disaster-affected community as patient partners starting from the conception phase of their studies. This will help gain insight into the reality of such vulnerable settings, overcome power differences, examine the phenomenon of interest from the lens of disaster-affected communities, and co-design need-based interventions. Involvement of the humanitarian relief organizations (governmental and non-governmental) as a collaborator and knowledge users is recommended to gain access to the disaster-affected communities, seek support in times of uncertainty, and for successful execution of the need-based programs, policies and practices in the post-disaster settings. The role of interdisciplinary and collaborative research in the post-disaster setting is vital in identifying need-based programs, policies and practices to improve the quality of life of the internally displaced population. The healthcare curriculum must include a preparatory course on disaster management to prepare the next generation of healthcare professionals and researchers who can demonstrate cultural competence and cultural humility during their fieldwork in post-disaster settings.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, [S.H], on special request.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the International Development Research Center (IDRC) [Grant#108544-007], Sigma Theta Tau International Small Research Grant (STTI) [Grant#13566], and the Canadian Institute of Health Research (CIHR) Vanier Canada Graduate Scholarship awarded to the author.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Dr. Shela Hirani is the Associate Editorial Board Member of the journal The Open Public Health Journal.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This paper is based on research conducted by the author in the post-disaster settings of Chitral, Pakistan. The author acknowledges the support of the Aga Khan Agency for Habitat (AKAH) and the thesis supervisory committee, including Dr. Solina Richter, Dr. Bukola Salami, and Dr. Helen Vallianatos.