RESEARCH ARTICLE

Linking Career Anxiety with Suicide Tendencies among University Undergraduates

Charity N. Onyishi1, *

Article Information

Identifiers and Pagination:

Year: 2023Volume: 16

Issue: Suppl-1, M2

E-location ID: e187494452302081

Publisher ID: e187494452302081

DOI: 10.2174/18749445-v16-230301-2022-HT21-4315-3

Article History:

Received Date: 28/09/2022Revision Received Date: 17/01/2023

Acceptance Date: 17/01/2023

Electronic publication date: 22/03/2023

Collection year: 2023

open-access license: This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Public License (CC-BY 4.0), a copy of which is available at: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/legalcode. This license permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Background:

Suicide is increasingly becoming a worldwide public health issue. The issue of suicide in universities is one of the most pressing concerns in Nigeria and the world. Yet, it has not been clear the factors that account for increased suicide among university students. This study investigated the link between career anxiety and suicidal tendencies among university undergraduates.

Methods:

The study was cross-sectional correlational and used a sample of 3,501 undergraduates in Nigeria. Career anxiety was measured using the two-factor career anxiety scale (CAS -2). At the same time, suicide tendencies were weighed using the Multi-attitude Suicide Tendency Scale (MAST), and Suicidal Ideation Attributes Scales (SIDAS).

Results:

Data collected were analyzed using percentages to interpret demographic data. Mean and standard deviation was presented for descriptive purposes. Linear regression was used to explore the links between career anxiety and suicidal tendencies at p < 0.05 level of significance. Results indicated that a high level of career anxiety was significantly correlated with increased suicidal tendencies, such as repulsion for life, attraction to death, and suicidal ideation. A low level of career anxiety was associated with decreased suicidal tendencies, characterized by an increased attitude toward attraction to life and repulsion to death.

Conclusion:

It was concluded that students with problematic career anxiety are likely to report a negative attitude toward life, which leads to increased suicidal ideation. Accordingly, career anxiety may cause one to seriously consider or contemplate suicide.

1. INTRODUCTION

The issue of suicide has been among the most pressing public health concerns in the world [1]. Suicide is responsible for 16 deaths per 100,000 people [2, 3]. This suggests that about 1.53 million death per year are due to suicide. Several studies have demonstrated that adolescents and young adults are at a higher risk for suicide tendencies [2, 4-7]. In recent years, suicide has been recognized as one of the top five mental health issues affecting university students worldwide (World Health Organization, 2019). Thus, suicide is the chief cause of death among university students [6, 8-12] and accounts for approximately 19% of all deaths in the undergraduate population [4].

It has been demonstrated in a number of studies that suicide is the primary or second leading cause of death among university students in various countries [1, 3, 5, 13]. A worldwide average of 32.7% of college students exhibit suicidal behavior. The number of college students who commit suicide each year is approximately 1100 (Abdu et al., 2020). Additionally, 6.4% to 9.5% of university students seriously consider suicide, and 1.3% to 1.5% attempt suicide by the end of the academic year [1]. According to recent studies conducted in South Africa [1, 2], 46.4% of university students had suicidal thoughts, 26.5% planned suicide, and 8.6% attempted suicide. According to the Ethiopian data, suicidal ideation, plan, and an attempt had life-time prevalence of 58.3%, 37.3%, and 4.4%, respectively, and the one-year prevalence of suicidal ideation was 34% [2]. Hence, suicide is a major cause of death among university students, with the tendency spreading with increasing life challenges in schools.

This study defined suicidal tendencies as all mental, physical, and behavioral propensities to commit suicide. It includes a multidimensional suicidal propensity, including suicidal ideation, planning, and attempts, as well as a multidimensional outlook on life and death [3, 10, 11, 14, 15]. An individual who has a suicidal tendency manifests one or more of the following suicidal behavior indices: (a) self-initiated, potentially lethal behavior [16-19]; (b) the presence of suicidal intent [20-23]; and (c) a nonfatal outcome [24] and related behaviors such as deliberate self-harm (DSH), non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI), suicidal threats, and suicidal gestures [10, 25]. Due to the recent increase in university student suicides in Nigeria, suicide research in Nigeria must pay attention to suicidal tendencies [26-28].

Additionally, indicators of suicidal tendencies are prevalent among university students in Nigeria [3, 27-29], including attempts to commit suicide and suicidal behaviors as well as other social risk behaviors such as drug overdose, poisoning, hanging, and well-jumping. Suicide ideation may be generated by some risk factors such as a stressful university experience that broken relationships may compound, the loss of loved ones, family mental health history, and feelings of failure, all of which contribute to depression and other co-occurring mental illnesses among students [30]. Further, the challenges of academic life, and the uncertainties associated with future career paths all may contribute to this phenomenon [26, 28]. University students can experience suicidal ideation at a critical time partly due to the transition from adolescence to young adulthood, or due to dissatisfaction with major life cursors such as career issues [30].

Research has investigated the protective and risk factors that contribute to a young person's suicidal ideation taking into consideration the multiple risk factors faced by university students [30]. Attempts made to investigate the biological, personal, and social causes of complete suicide have discovered that apart from academic stress [26, 28, 31] significantly predicting suicidal ideation, career issues may be of greater contributing influence among undergraduates [22]. Since suicide is a psychosocial/health issue in Nigeria, research [28] has recommended exploring variables such as social background, and other demographic variables, including career-related variables.

Suicidal behavior among university students in Nigeria is a national concern. This is because the university students are still at a productive age, and the population is extremely important to the nation's economic and social development. The rising incidence of suicide among the university thus threatens the future human capital and the country’s economy. Yet, it is my understanding that no study has examined the impact of career-related concerns on suicidal tendencies among Nigerian university students. Recent researchers are increasingly concerned about how career anxiety can contribute to the multi-faceted mental well-being of college students [32-36] and how it can contribute to increased suicide among students. Most young adults experience career anxiety at some point in their lives. Career anxiety may be most common among university students with occupational indecision and uncertain futures as they make life-altering decisions during their university years.

In such respect, anxiety arises from an individual's concerns about his or her academic and professional future, as well as fear of disappointing family members and being forced to move away from the expectations of family and friends [32-36]. In other words, the anxiety associated with career development may arise during university school in many different subjects, including failing to satisfy family expectations, not achieving the desired goals, not being able to select the preferred occupation, or failing to meet expectations associated with the desired career.

Career anxiety is defined in terms of family influence and choice of profession in studies conducted with high school students in Turkey [14, 27]. Consequently, for the dimension of “career anxiety for the influence of family”, Students in high school feared that their families would misunderstand their career goals or prevent them from pursuing them. Concerning the “career anxiety in relation to the choice of profession” component, high schoolers were worried about the suitability of the job they desired, their level of happiness, and the likelihood of dissatisfaction. In relation to the influence of family on career selection and outcome [14], the family effect can result in difficulties with decision-making [37], and anxiety for adolescents. Those having difficulty in making career or professional choices generally report career anxiety [38], and such condition appears to strengthen the opinion that family factors constitute a part of career anxiety.

Similarly, the choice of profession is a multi-dimensional process, and in the educational structure, it focuses mainly on academic success. Sometimes, career anxiety among university students may be born out of regrets of not meeting with admission into the choice cause, fear of disappointing family members on the choice made, academic challenges of course failures, being pushed by significant others into courses that do not align with the identified aptitude, or uncertainties about the prospects of their courses. As a result, the majority of university students experience career choice anxiety as one of the dimensions of career anxiety. It is believed that career anxiety is a form of social anxiety because it relates to an individual's status in society as a student or as a professional. Progressively, career anxiety increases throughout adolescence. Students are increasingly concerned about their career and academic futures [38, 39]. Career anxiety can either be an indicator of career indecision or a factor of it when it is more severe [39].

It is worthy of note that no matter the source, anxiety has been identified as one of the risk factors for suicide. Bentley et al. [40], indicated that anxiety is a statistically significant predictor of suicide ideation and attempts. Nepon et al. [41], found that 70% of individuals reporting a lifetime history of suicide attempts had an anxiety disorder. Other current studies have linked anxiety to suicide tendencies, including suicide ideation [6, 11, 42-44], suicide behaviours [31, 44, 45], and suicide attempts [5]. However, most studies focused on generalized anxiety disorders, which are rarely peculiar to university environments.

Relatedly, the increasing incidences of suicide in Nigerian universities call for increased efforts towards finding out the factors around university experiences that constitute the impending causes of suicide among undergraduate students. Regrettably, this area has been generally overlooked in Nigeria. This may be due to the culturally-based stigma associated with suicide and suicidal behaviors in Nigeria [27]. For instance, suicidal attempt is still a criminal offence and suicidal act is still a cause of high social stigma for the family victims in Nigeria [46]. In this regard, both policy and research tend to give less attention to the factors leading to suicide, due to the beliefs on the mystical explanation [47].

Hence, in spite of the increasing prevalence of suicide in the university students, it has remained a mystery as to whether such factors as career difficulties could account for increased suicide tendencies among undergraduates. The area of career anxiety is the most overlooked among the university-based risk factors of suicide. Additionally, no study to the best of my knowledge had inquired into whether career-related anxiety would predict university students’ propensity to commit suicide. This study investigated the predictive link between suicidal tendencies and career anxiety, with a view to establishing if anxiety associated with future career accounts for the increasing burden of suicide in university students.

1.1. Research Questions and Hypotheses

With the problem of suicide increasing in the Nigerian Universities, researchers are increasingly concerned about the peculiar factors that predispose university students to suicide. Such predisposing factors that can cause suicidal tendencies could be genetic psychological or environmentally generated potential risk factors. Prior studies have explored most of such factors such as psychosocial risk factors that predispose University students to suicide ideation such as Facebook addiction, depression, anxiety [43-45], as and family cohesion [48]. Other potential risk factors are additionally identified, including bullying experience, mental illness, a history of sexual assault by or to a close family member and underlying chronic illness [49]. A related study further showed that economic class, sexual orientation, religious practice, suicide attempts in the family and alcohol consumption were significantly associated with suicide ideation [50]. Career related issues are the least researched among the factors that could account for suicide. Though anxiety has been found to be significantly associated with suicide tendencies [43], most of such studies addressed generalized anxiety [43-48]. It is not clear whether specific anxiety about career path can be linked to suicidal tendencies. The current study investigated the link between career anxiety and suicidal tendencies. Thus, data were collected to answer the following questions: i) what are the relationships between career anxiety and dimensions of suicide tendencies? ii) to what extent can career anxiety predict suicide tendencies? It is further hypothesized that: i) there will be substantial positive linkages between the subscales career anxiety, and all dimensions of suicide tendencies; ii) career anxiety subscales will predict suicide tendencies.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Design and Ethics

This research was a cross-sectional study conducted with university undergraduates. Participating in the study was voluntary and before taking part in the study, prospective participants provided informed consent online. Additionally, the study was approved by the Ethics Committee of a university in Nigeria, with the reference Number: REC/ED/22/00017. Suicide prevention resources were made available to the participants that took part in this survey.

2.2. Participants and Procedure

A battery of online questionnaires was sent to university students. During the period of April 1-30, 2022, the questionnaires prepared with Google Forms were shared through WhatsApp. Inclusion criteria included full-time university students, including undergraduates, studying in Nigerian universities, with an average age of 20 years and 2.70 years. Eligibility criteria include that: i) prospective participants must be an undergraduate in a Nigerian University. ii) participant is willing to participate in the study, and signs consent form. Participants who did not complete the questionnaire were excluded from the study. The online questionnaire was completed by 3,501 students during the period of data collection.

2.4. Assessment of Career Anxiety

The university students’ career anxiety was measured using the two-factor career anxiety scale (CAS -2) version 2 used by Nalbantoğluand colleagues [51]. There are two factors and fourteen items in the Career Anxiety Scale. A 5-point Likert scale was used to assess the responses to the scale items ranging from ” 1-strongly disagree” to ” 5-totally agree”. Those with high scores on each dimension of the scale are more likely to experience career anxiety on that dimension. It consists of two factors, the first measuring career-related anxiety and the second measuring family-related anxiety. In order to establish the instrument's reliability, the Cronbach Alpha coefficient was calculated. In this study, the Cronbach Alpha internal consistency coefficient and the first factor's reliability coefficient were calculated. A reliability coefficient was determined for the first and second factor, which were 79 and 81, respectively.

The Multi-attitude Suicide Tendency Scale (MAST) is a 30-item scale that reflects 4 types of attitudes: attraction towards and repulsion to life and death [52]. MAST is measured on a 5-point scale of 1 = Strongly disagree‚ 2 = Don’t agree‚ 3 = Sometimes agree‚ Sometimes disagree‚ 4= Agree‚ 5= Strongly Agree. Individuals' attraction to life (AtL) is influenced by their sense of safety in social interactions, romantic relationships, need satisfaction, and self-esteem. AtL is also determined by ego-strength, coping mechanism. The individual's pain and suffering when confronted with unfathomable problems is reflected in feelings of aversion towards life, referred to as “Repulsion from Life (RFL)”. In general, RFL can be viewed as a drive toward self-harm.

Attraction to death (AtD) encapsulates the notion that death is superior to life and therefore is a better mode of emotional existence. This perspective encompasses the notion that all of one's passions are satisfied in death and that death is recoverable or a blissful, serene, and relaxing state. Teenagers frequently glamorize death and view it as a magical alliance with a universal entity that provides cover and vigor. These fantasies promote suicidality because they raise attraction to death and serve as a motivating force for self-destruction. Even among those with strong inclinations to self-destruction, aversion to death is prevalent; it stems from the realistic, terrifying perception of death as the irreversible cessation and annihilation of life but is also influenced by the individual's inner world. Consequently, an expectation of severe penalty after dying could be an expression of extreme guilt. Death's repugnance is a force that discourages self-destruction. Although intertwined, the four sentiments do not depict the same subjective feelings.This instrument was validated by Osman et al., (1993, 2000) [53] and showed good psychometric quality. Its overall reliability in this study (α= .88) was also strong.

2.5. Assessment of Suicide Ideation

Suicidal Ideation Attributes Scales (SIDAS) were utilized to assess suicidal ideation (Van Spijker et al., 2014) [15]. SIDAS was an 11-point Likert scale containing five questions regarding the frequency and intensity of suicidal thoughts, such as “In the past month, to what extent have you felt tormented by suicidal thoughts?” The scale includes the question, “How often have you had suicidal thoughts in the past month?” (0 Never, 1–9: unlabeled points, 10 Always); 2. “How much control have you had over these thoughts in the past month?” (0 No control/do not control, 1–9: unlabeled points, 10 Full control); 3. “How close were you to attempting suicide in the past month?” (0 Not even close, 1–9: unlabeled points, 10 Have attempted suicide) 4. “In the past month, to what extent have you been tormented by suicidal thoughts?” (0 Not at all, 1–9: unlabeled points, 10 Extremely); and, 5. “In the past month, to what extent have suicidal thoughts interfered with your ability to engage in daily activities, such as work, household chores, or social interactions?” (0 Not at all, 1–9: points without labels, 10 Extremely). Reverse-scoring was used to calculate a total score for the degree of suicidal ideation by adding the scores of each item. A participant with a higher total SIDAS score had greater suicidal ideation. Cronbach's alpha coefficient of 0.89 indicated that the convergent validity and internal consistency of the SIDAS were satisfactory.

2.6. Data Analysis

Percentages were used to interpret demographic data. Mean and standard deviation were presented for descriptive purposes. Links between career anxiety and suicidal tendencies were explored using logistic regression. The level of significance was set at p < 0.05 (two-tailed). SPSS version 24 was used to conduct the analyses. In the predictor effect model, career anxiety variables were the independent variables, suicide tendency concepts were dependent variable. All data were presented in tables.

3. RESULTS

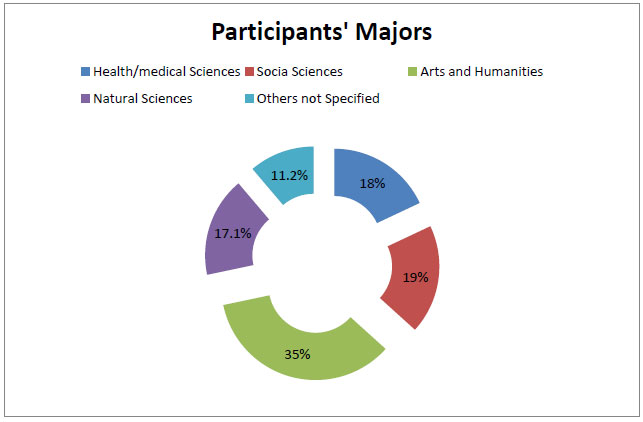

Participants’ demographic information is presented in figures and charts. Fig. (1) shows the distribution of the study participants according to their university majors. As shown in Fig. (1), 18.0% of the students were in the health/medical sciences, 18.7% were in Social Science, 35.0% were in arts and humanities, 17.1% were in Natural sciences, and 11.2% were in others not classified.

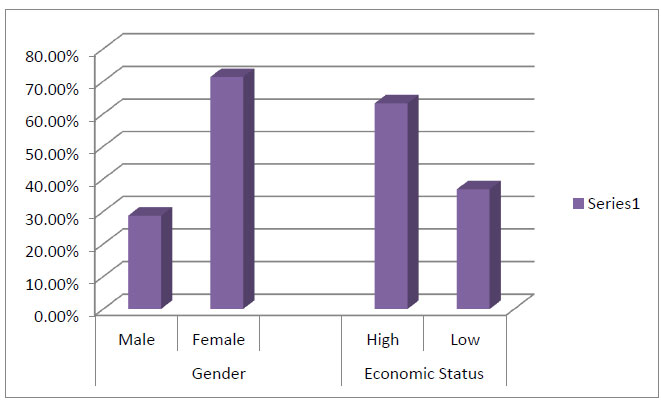

Further, the participants’ gender and economic status are shown in Fig. (2). It shows that 71.3% of the students who participated in the study were female, while 28.7% were males. Considering the economic status of the participants, 63.2% had balanced income/expenses (high economic status), while 36.8% were without income-expenses balance (low economic status) (Fig. 2).

Mean, standard deviations and correlation coefficients among Career anxiety, attraction / repulsion to life, attraction / repulsion to death, and suicidal ideation were shown in Table 1. As expected, increased career anxiety showed a significant correlation with greater attraction to life (r =-.31, and a significant decrease in the feeling of repulsion to life (r =-.31). A high level of career anxiety is further linked to an increased sense of attraction to death (r =.21) and decreased repulsion to death (r =-.61). Considering suicidal ideation, higher career anxiety was significantly associated with a stronger suicidal ideation score.

The results of regression analyses are presented in Table 2. CAS score was found to predict three subscales of the Multi-attitude Suicide Tendency Scale. According to Table 2, CAS was a significant negative predictor of attraction to life (B = -.22, t = -12.23, p < .001) and a positive predictor of repulsion to life (B = -.19, t = 3.38, p < .001).CAS as also a significant positive predictor of attraction to death (B = .23, t = 9.33, p < .001), and a non-significant predictor of repulsion to death (p > .001). These imply that a unit increase in career anxiety level causes. 22 reduction in students’ attraction to life score and .19 increase in repulsion by life. Further, a unit increase in the CAS score accounts for .23 increase in the score of attraction to death and .10 decrease in repulsion to death. These suggest that career anxiety id a significant risk factor for tendencies toward suicide.On the other hand, CAS score significantly predicted suicide ideation (B = .31, t = 23.11, p < .001) in the current sample of university students. This regression model showed that career anxiety accounted for .31 increase, which is also about 31% if the overall variance in suicidal ideation. These results suggest that career anxiety is a major risk factor for suicide ideation among university students in Nigeria.

|

Fig. (1). Graphic representation of participants’ university majors. |

|

Fig. (2). Bar chart showing participants’ gender and economic status. |

| Variable | Scale | Mean (SD) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAS | 1 | CAS Score | 42.38 | - | .23** | -.31** | .21** | .19 | 50*** |

| MAST | 2 | Attraction to life | 3.47 (1.33) | - | - | -.23** | -.61*** | .47*** | -.33*** |

| 3 | Feelings of repulsion by life | 2.39 (0.97) | - | - | - | -.55*** | .44*** | .54*** | |

| 4 | Attraction to death | 2.07 (.50) | - | - | - | - | -.53*** | .61*** | |

| 5 | Repulsion by death | 1.32 (.30) | - | - | - | - | - | -.66*** | |

| SIDAS | 6 | SIDAS score | 20.71 (5.80) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Independent Variable | Dependent Variable | B | SE | Β | T | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAS Score | Attraction to life | -.22 | .10 | -.23 | -12.23 | *** |

| - | Feelings of repulsion by life | .19 | .10 | .31 | 3.58 | *** |

| - | Attraction to death | .23 | .01 | .21 | 9.33 | *** |

| Repulsion by death | -.10 | .01 | -.59 | -1.76 | .450 | |

| SIDAS score | .31 | .11 | .49 | 23.11 | *** |

4. DISCUSSION

This study sought to inquire whether career anxiety could predict of suicidal ideation among undergraduate students in Nigeria. Suicidal tendencies were hypothesized to be significantly correlated with career anxiety. As predicted by our hypothesis, high levels of career anxiety were significantly correlated with increased suicidal tendencies, such as feelings of repulsion for life, attraction to death, and suicidal ideation. A low level of career anxiety was associated with decreased tendencies, characterized by an increased attitude toward attraction to life and repulsion of death. According to previous research, relatedness and suicidal tendencies are significantly correlated in both young and older adults [26, 54]. While no specific studies have investigated the relationship between career anxiety and suicidal tendencies, there is some evidence that suggests that anxiety disorders may be linked to suicide behaviors [5, 30, 40, 41, 44, 45]. Further, this study indicates an association between suicidal ideation and this association, as well as the high prevalence rate of suicidal ideation found in an earlier study [3, 55] may be justified.

Given the increasing suicide rates among university students in Nigeria over the past few decades, these findings are invaluable [3]. Students who are in late adolescence and in the critical phase of transitioning from adolescence to adulthood may develop an adverse outlook on life and death due to their experiences [56, 57]. There is a significant threat to young adults when they are surrounded by uncertainties regarding their future careers and independence/responsibility as adults (Hardie, 2009) [58]. According to previous research, career aspirations are generally invariant across age cohorts and over time [57], but they may become more anxiety-provoking during the transition from childhood to adulthood [7, 58]. During that period, students may come to realize that their career will affect their entire life and livelihood [39]. According to these results, I concur with prior studies in which it has been demonstrated that finding a rewarding and appropriate career gives youths a sense of mental and psychological stability [1, 38].

Hence, given that completed suicide states from negative outlook [1] and thoughts [42, 58]. This study provides evidence that suicide management should consider key factors that predispose university students to suicide. The outcomes of this study can be generalized across university students in Nigeria only as the socio-cultural and economic situation in Nigeria may have impacted the respondents. It may therefore be necessary to provide career counseling and support for university students in order to minimize suicide tendencies.

5. LIMITATIONS OF THE STUDY AND SUGGESTIONS FOR FURTHER STUDIES

There are cultural biases and stereotypes associated with suicide in Nigeria that may have influenced the outcome current study. It would therefore be reasonable to assume that the self-report measure may not have fully captured the details of the sample's intent toward suicide. Further studies may consider using special groups, such as those who have attempted suicide and ascertain their reasons for the attempt. Interviews may be considered for further research in order to establish positive relationships regarding students’ reasons for considering suicide.

This study only addressed career anxiety and suicide without considering other university-based factors such as academic achievement. Further studies could include educational stress scale to make a clear distinction about which factor most explains undergraduate suicidal propensity. Further studies can also consider comparing suicidal risk levels at different stages of life between university students and high school students to establish the influence of the adolescence stage and the process of transition to adulthood on suicide intentions. It would be helpful to know if the propensity for career anxiety and suicidal behavior starts in adolescent years and is only exacerbated at the university level by certain social risk behaviors, thus, a longitudinal study is recommended for future study to address a such concern. Further studies should investigate the in-depth university-based risk factors for suicide as the incidences are becoming overwhelming for the Nigerian university system, such as poverty, academic achievement, student-lecturer relationships, poor achievements, and others. Studies investigating the actual causes of pathological career anxiety may be helpful for policy and decision-making.

CONCLUSION

The purpose of this study was to examine the relationship between career anxiety and suicide tendencies among undergraduates in Nigeria for the first time. It was hypothesized that there would be There is a significant positive correlation between both career anxiety subscales and suicidal tendencies; ii) career anxiety predicts suicide tendencies. Therefore, students with problematic career anxiety are likely to report a negative attitude toward life, which leads to increased suicidal ideation. According to the present study, career anxiety accounted for 19% repulsion to life, 23% attraction to death, and 33% increase in suicidal ideation. According to the findings of the study, career anxiety may cause one to consider or contemplate suicide seriously.

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

This study was approved by the Faculty of Education committee, University of Nigeria, Nasukka. (REC/ED/22/00017).

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

No animals were used for studies that are the basis of this research. All the humans were used in accordance with the ethical standards of the committee responsible for human experimentation (institutional and national), and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2013 (http://ethics.iit.edu/ecodes/node/3931).

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Participating in the study was voluntary and before taking part in the study, prospective participants provided informed consent online.

STANDARDS OF REPORTING

STROBE guidelines were followed.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

The data supporting the findings of the article is available from the corresponding author [C.N.O] at reasonable request.

FUNDING

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The author declares no conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| MAST | = Multi-Attitude Suicide Tendency Scale |

| SIDAS | = Suicidal Ideation Attributes Scales |

| NSSI | = Non-Suicidal Self-Injury |

REFERENCES

| [1] | Pillay J. Suicidal behaviour among university students: A systematic review. S Afr J Psychol 2021; 51(1): 54-66. |

| [2] | Abdu Z, Hajure M, Desalegn D. Suicidal behavior and associated factors among students in Mettu University, South West Ethiopia, 2019: An institutional based cross-sectional study. Psychol Res Behav Manag 2020; 13: 233-43. |

| [3] | Owusu-Ansah FE, Addae AA, Peasah BO, Oppong Asante K, Osafo J. Suicide among university students: prevalence, risks and protective factors. Health Psychol Behav Med 2020; 8(1): 220-33. |

| [4] | Al Zoubi SM. The impact of exposure to English language on language acquisition. J Appl Linguist Lang Res 2018; 5(4): 151-62. |

| [5] | Chen H. The association between suicide attempts, anxiety, and childhood maltreatment among adolescents and young adults with first depressive episodes. Front Psychiatry 2021; 12: 745470. |

| [6] | Mackenzie S, Wiegel JR, Mundt M, et al. Depression and suicide ideation among students accessing campus health care. Am J Orthopsychiatry 2011; 81(1): 101-7. |

| [7] | Urme SA, Islam MS, Begum H, Awal Chowdhury NMR. Risk factors of suicide among public university students of Bangladesh: A qualitative exploration. Heliyon 2022; 8(6): e09659. |

| [8] | Turner JC, Leno EV, Keller A. Causes of mortality among American college students: A pilot study. J Coll Stud Psychother 2013; 27(1): 31-42. |

| [9] | Barrios LC, Everett SA, Simon TR, Brener ND. Suicide ideation among US college students. Associations with other injury risk behaviors. J Am Coll Health 2000; 48(5): 229-33. |

| [10] | Bridge JA, Goldstein TR, Brent DA. Adolescent suicide and suicidal behavior. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2006; 47(3-4): 372-94. |

| [11] | Nock MK, Borges G, Bromet EJ, Cha CB, Kessler RC, Lee S. Suicide and suicidal behavior. Epidemiol Rev 2008; 30(1): 133-54. |

| [12] | Rudd MD. The prevalence of suicidal ideation among college students. Suicide Life Threat Behav 1989; 19(2): 173-83. |

| [13] | Kisch J, Leino EV, Silverman MM. Aspects of suicidal behavior, depression, and treatment in college students: Results from the spring 2000 national college health assessment survey. Suicide Life Threat Behav 2005; 35(1): 3-13. |

| [14] | Brent DA. Risk factors for adolescent suicide and suicidal behavior: Mental and substance abuse disorders, family environmental factors, and life stress. Suicide Life Threat Behav 1995; 25: 52-63. |

| [15] | van Spijker BAJ, Batterham PJ, Calear AL, et al. The suicidal ideation attributes scale (SIDAS): Community-based validation study of a new scale for the measurement of suicidal ideation. Suicide Life Threat Behav 2014; 44(4): 408-19. |

| [16] | Dash S, Taylor T, Ofanoa M, Taufa N. Conceptualisations of deliberate self-harm as it occurs within the context of Pacific populations living in New Zealand. N Z J Psychol 2017; 46(3): 115-25. |

| [17] | De Leo D, Burgis S, Bertolote JM, Kerkhof AJFM, Bille-Brahe U. Definitions of suicidal behavior: Lessons learned from the WHo/EURO multicentre Study. Crisis 2006; 27(1): 4-15. |

| [18] | Gregory G. Queering suicide: Complicated discourses, compiled deviances, and communal directives surrounding LGBTQIA+ intentional self-initiated death. Honors Thesis. 2019. |

| [19] | Posner K, Brodsky B, Yershova K, Buchanan J, Mann J. The classification of suicidal behavior. In: The Oxford Handbook of Suicide and Self-Injury. Oxford University Press 2014; pp. 7-22. |

| [20] | Korn ML, Plutchik R, Van Praag HM. Panic-associated suicidal and aggressive ideation and behavior. J Psychiatr Res 1997; 31(4): 481-7. |

| [21] | Kumar M, Dredze M, Coppersmith G, De Choudhury M. Detecting changes in suicide content manifested in social media following celebrity suicides Proceedings of the 26th ACM conference on Hypertext & Social Media. 85-94. |

| [22] | Howard MC, Follmer KB, Smith MB, Tucker RP, Van Zandt EC. Work and suicide: An interdisciplinary systematic literature review. J Organ Behav 2022; 43(2): 260-85. |

| [23] | Beck AT, Kovacs M, Weissman A. Assessment of suicidal intention: The Scale for Suicide Ideation. J Consult Clin Psychol 1979; 47(2): 343-52. |

| [24] | De Choudhury M, Kiciman E, Dredze M, Coppersmith G, Kumar M. Discovering shifts to suicidal ideation from mental health content in social media Proceedings of the 2016 CHI conference on human factors in computing systems. 2098-110. |

| [25] | Brent DA, Kerr MM, Goldstein C, Bozigar J, Wartella M, Allan MJ. An outbreak of suicide and suicidal behavior in a high school. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1989; 28(6): 918-24. |

| [26] | Nkwuda FCN, Ifeagwazi CM, Nwonyi SK, Oginyi RC. Suicidal ideation among undergraduate students: Academic stress and self-esteem as predictive factors. Niger J Psychol Res 2020; 16(1) |

| [27] | Oyetunji TP, Arafat SMY, Famori SO, et al. Suicide in Nigeria: Observations from the content analysis of newspapers. Gen Psychiatr 2021; 34(1): e100347. |

| [28] | Sonia O. Suicidal ideation among Undergraduates in Nigeria: The predictive role of personality traits and academic stress. 9(2)2020; |

| [29] | Adewuya AO, Ola BA, Coker OA, et al. Prevalence and associated factors for suicidal ideation in the Lagos State Mental Health Survey, Nigeria. BJPsych Open 2016; 2(6): 385-9. |

| [30] | Simon NM, Zalta AK, Otto MW, et al. The association of comorbid anxiety disorders with suicide attempts and suicidal ideation in outpatients with bipolar disorder. J Psychiatr Res 2007; 41(3-4): 255-64. |

| [31] | Pandey GN. Biological basis of suicide and suicidal behavior. Bipolar Disord 2013; 15(5): 524-41. |

| [32] | Vignoli E. Career indecision and career exploration among older French adolescents: The specific role of general trait anxiety and future school and career anxiety. J Vocat Behav 2015; 89: 182-91. |

| [33] | Mallet P, Vignoli E. Intensity seeking and novelty seeking: Their relationship to adolescent risk behavior and occupational interests. Pers Individ Dif 2007; 43(8): 2011-21. |

| [34] | Vignoli E, Nils F, Parmentier M, Mallet P, Rimé B. The emotions aroused by a vocational transition in adolescents: why, when and how are they socially shared with significant others? Int J Educ Vocat Guid 2020; 20(3): 567-89. |

| [35] | Vignoli E, Croity-Belz S, Chapeland V, de Fillipis A, Garcia M. Career exploration in adolescents: The role of anxiety, attachment, and parenting style. J Vocat Behav 2005; 67(2): 153-68. |

| [36] | Career indecision and career anxiety in high school students: An investigation through structural equation modelling. Eurasian J Educ Res 2018; 18(78): 23-42. |

| [37] | Finding an appropriate and lucrative career gives mental and psychological stability to youths - Google Search. Available from: https://www.google.com/search?q=Finding+an+appropriate+and+lucrative+career+gives+mental+and+psychological+stability+to+youths&oq=Finding+an+appropriate+and+lucrative+career+gives+mental+and+psychological+stability+to+youths&aqs=chrome.69i57.1779j0j15&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8 |

| [38] | Akosah-Twumasi P, Emeto TI, Lindsay D, Tsey K, Malau-Aduli BS. A systematic review of factors that influence youths career choices—the role of culture. Front Educ 2018; 3: 58. |

| [39] | Mann A. Teenagers’ career aspirations and the future of work. OECD Publishing. 2020. Available from: https://www. oecd. org/education/dream-jobs |

| [40] | Bentley KH, Franklin JC, Ribeiro JD, Kleiman EM, Fox KR, Nock MK. Anxiety and its disorders as risk factors for suicidal thoughts and behaviors: A meta-analytic review. Clin Psychol Rev 2016; 43: 30-46. |

| [41] | Nepon J, Belik SL, Bolton J, Sareen J. The relationship between anxiety disorders and suicide attempts: Findings from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Depress Anxiety 2010; 27(9): 791-8. |

| [42] | Ajibola AO, Agunbiade OM. Suicide ideation and its correlates among university undergraduates in south western Nigeria. Int Q Community Health Educ 43: 0272884x2170049. |

| [43] | Mamun MA, Rayhan I, Akter K, Griffiths MD. Prevalence and predisposing factors of suicidal ideation among the University students in Bangladesh: A single-site survey. Int J Ment Health Add 20(4): 1958-71. |

| [44] | Sareen J, Cox BJ, Afifi TO, et al. Anxiety disorders and risk for suicidal ideation and suicide attempts: A population-based longitudinal study of adults. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005; 62(11): 1249-57. |

| [45] | Zhou SJ, Wang LL, Qi M, et al. Depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation in chinese university students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Psychol 2021; 12: 669833. |

| [46] | Alabi OO. Suicide and suicidal behaviours in Nigeria, a review. Dokita 2015; 5: 4. |

| [47] | Omomia OA. Religious Perceptions of Suicide and Implication for Suicidiology Advocacy in Nigeria. Int J Hist Philosop Res 2017; 5(2): 34-56. |

| [48] | Gençöz T, Or P. Associated factors of suicide among university students: Importance of family environment. Contemp Fam Ther 2006; 28(2): 261-8. |

| [49] | Alabi A A, Oladimeji O K, Adeniyi OV. Prevalence and factors associated with suicidal ideation amongst college students in the Nelson Mandela Bay Municipality, South Africa. South African Family Practice 63(1)2021; : e1-9. |

| [50] | Hugo S. Factors associated with suicidal ideation among university students. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem 2017; e25: e2878. |

| [51] | Nalbantoğlu Yılmaz F, Çetin Gündüz H. Measurement invariance testing of career anxiety scale by gender and grade level. Sakarya Univ J Edu 2022; 12(1): 95-107. |

| [52] | Orbach I, Milstein I, Har-Even D, Apter A, Tiano S, Elizur A. A multi-attitude suicide tendency scale for adolescents. Psychol Assess 1991; 3(3): 398-404. |

| [53] | Osman A, Barrios FX, Grittmann LR, Osman JR. The multi-attitude suicide tendency scale: Psychometric characteristics in an american sample. J Clin Psychol 1993; 49(5): 701-8. |

| [54] | Osman A, Gilpin AR, Panak WF, et al. The multi-attitude suicide tendency scale: Further validation with adolescent psychiatric inpatients. Suicide Life Threat Behav 2000; 30(4): 377-85. |

| [55] | Anny Chen LY, Wu CY, Lee MB, Yang LT. Suicide and associated psychosocial correlates among university students in Taiwan: A mixed-methods study. J Formos Med Assoc 2020; 119(5): 957-67. |

| [56] | Namazzi G, Hildenwall H, Mubiri P, et al. Prevalence and associated factors of neurodevelopmental disability among infants in eastern Uganda: A population based study. BMC Pediatr 2019; 19(1): 379. |

| [57] | Wood D. Emerging Adulthood as a Critical Stage in the Life Course. In: Handbook of Life Course Health Development. Cham: Springer 2018; pp. 123-43. |

| [58] | Hardie JH. How aspirations are formed and challenged in the transition to adulthood and implications for adult well-being - PhD Thesis, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. 2009. |