All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

‘I asked myself why I was having this difficult child’: Care Burden Experiences of Black African Mothers Raising A Child with Autistic Spectrum Disorder

Abstract

Introduction:

There is increasing recognition that raising a child with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is stressful and challenging, particularly for mothers in resource-constrained countries. The aim of this study was to learn more about the experiences of black African mothers raising children with ASD and to gain a better understanding of the care burden.

Methods:

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with nine purposively recruited mothers of children with ASD and analysed using interpretative phenomenological analysis.

Results:

The findings revealed that caring for children with ASD puts a tremendous psychological, emotional, and financial strain on mothers. Mothers commonly faced social judgment and stigma, which manifested as internalized self-blame, isolation, and social exclusion for both themselves and their children.

Conclusion:

The findings highlight the critical need to increase psychosocial support for mothers of children with ASD who live in resource-constrained countries.

1. INTRODUCTION

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a complex neurological disorder with growing global health concerns [1]. ASD is characterized by impaired neurodevelopment in social interaction and communication [2]. In addition, children with ASD have difficulty in developing appropriate relationships and they exhibit a variety of maladaptive functioning with restrictive patterns of behaviour, interest, and activities. The number of children affected by ASD has risen dramatically over the years [3]. Globally, one out of every 160 children is estimated to have ASD and while the burden of ASD in Africa is still unclear, the evidence does suggest that ASD is a major contributor to the burden of disability worldwide [4]. Despite limited research on the prevalence of ASD in Africa, it is estimated that approximately two percent of the South African population has ASD. South Africa remains the center of most ASD research in sub-Saharan Africa, and the evidence suggests that there is a progressive increase in the incidence of ASD [5].

ASD is often co-morbid with other developmental disorders, such as intellectual impairment, disruptive behaviour, attention difficulties, aggression, epilepsy, and psychomotor coordination difficulties [6]. In sub-Saharan Africa, intellectual disability, epilepsy, and attention deficit disorder were the most common co-morbid diagnoses for children with ASD [5].

Family caregivers play an important role in managing different aspects of the care of children with autism. Some researchers described ASD as a debilitating disorder that requires a lifetime commitment of care from parents due to the demanding and overwhelming nature of the disorder [7]. Mothers are much more involved in the raising of children and hold much of the caregiving responsibility. As such, there is growing interest regarding the caregiver burden of mothers raising children with autism spectrum disorders. Previous research has shown the developmental, health, and behavioural difficulties associated with ASD are not only challenging for the affected children but also for mothers raising children with ASD [8].

The evidence shows that caring for a child with ASD can be very costly for mothers’ mental, emotional, social, and physical health. Notably, mothers of children with ASD endure greater burdens in the form of fatigue, high levels of stress, anxiety, and depression compared to mothers of healthy, neurotypically developed children or chronically ill or disabled children [9]. Several studies showed that mothers raising children with ASD reported various challenges, including guilt, shame, and self-blame [10]; the strain on spousal relationships and typical developing siblings [8]; decreased social support [11]; worry, stress, and fear [12]. Moreover, mothers raising children with ASD perceived and experienced stigma that is associated with loneliness, social isolation, and exclusion [13, 14], which influenced their parental self-esteem and self-worth as caretakers of children with a disability [10, 15].

Previous research showed that many families confront financial difficulties in covering the expenses of raising a child with special needs. For example, the lifelong expenditure of ASD, including special schooling, medication, and psychological treatment costs, has been shown to be an important contributor to parenting stress and caregiver burden [16, 17]. The research showed that raising a child with ASD costs at least twice the cost of raising a neurotypically developing child [18]. Several studies from both developed and resource-constrained countries showed that having a child with ASD placed a high load on family finances, and even more so on families with no or limited financial resources and decreased access to public health services [5, 19-21]. For mothers raising children with ASD, the financial burden is often worsened because many of them are unable to work outside the home due to the extensive need for care of their children [18].

As the primary caregivers of children with ASD, mothers face tremendous parenting stress [22]. The added responsibilities of care brought on by ASD can be especially overwhelming and daunting for mothers. In South Africa [23], like many other low-middle-income countries [24], services specifically designed for children with ASD are not readily available in the public sector, which may impose additional strain on mothers. Although the healthcare service needs of children with ASD may be similar across the world, the nature of the resources needed by African children and the availability of supportive resources to African families are comparably different in high-income countries [25]. Thus, South African mothers of children with ASD are expected to experience greater caregiving burdens.

Notably, research on the lived experiences of mothers raising children with ASD in South Africa is largely unexplored, and more specifically, the caregiving burden has rarely been addressed. Caregiving burden [26], defined as the strain of providing care to family with disability, has been shown to have a negative impact on caregivers’ social, occupational, and personal roles and health outcomes. It is important to gain insight into mothers’ lived experiences since raising a child on the autism spectrum has been shown to be associated with a greater caregiving burden and negative health outcomes for mothers and their children [27].

2. METHODOLOGY

2.1. Aim and Objectives

The present study aimed to explore the caregiving burden experiences of mothers raising children with ASD in South Africa. The deliberate one-sided focus on burden is an important area of research to gain insight into the demands mothers experience caring for children with autism, and discover efficacious interventions that can promote the psychosocial and health needs of mothers of children with ASD in South Africa.

2.2. Research Approach and Design

The study adopted an exploratory qualitative approach to gain insight into the lived experiences and caregiving burdens of black African mothers raising children with ASD. Through interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA), the in-depth interviews of each of the participants were evaluated to capture both distinct and shared expressions (such as feelings and beliefs) about the challenges of raising a child with ASD [28].

2.3. Participants

A non-probability sample comprising nine mothers, all of whom were raising a child with a confirmed DSM-5 diagnosis of ASD aged four to 11 years, was included in the study. All of the mothers self-identified as black African and were between the ages of 30 and 51 years old. As seen in Table 1, almost two-thirds of the participants (6 out of 9) had a son, while three mothers had a daughter with ASD. Only twenty-two percent of the children had comorbid diagnoses. Of the nine participants, four were married, while three were single mothers raising children with ASD. Most participants were mothers who were employed (n = 8). Most (n = 5) had more than one child. To ensure that the narratives of the participants reflected the mothers' experiences rather than an account of adjusting to the initial diagnosis of their child’s ASD, mothers of children who had received a diagnosis of ASD less than one year prior to the data collection were not included in the study.

2.4. Data Collection Procedure

First, all the participating mothers completed a sociodemographic questionnaire (e.g., age, age of the child, gender of the child, marital status, etc.) that provided relevant background information about the families.

| Mothers’ Data | Children Data | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participants (Pseudonyms) (MASDC) | Age | Marital Status | Profession | Child’s Gender | Child’s Age | Comorbid Diagnoses | Birth Order |

| Ntsiki | 45 | Married | Environmentalist | Male | 11yrs | VI | Last of 3 children |

| Moleboheng | 36 | Married | Unemployed | Male | 6yrs | No | Last of two children |

| Nokuzola | 34 | Single | Banker | Female | 7yrs | No | Only child |

| Thandiwe | 38 | Divorced | Human Resources | Male | 11yrs | No | 2 boys (both have ASD) |

| Mamsie | 30 | Single | Administrator | Male | 5yrs | No | Only child |

| Deliwe | 51 | Widowed | Cleaner | Male | 11yrs | Epilepsy | Last born of 3 children |

| Lwandle | 30 | Married | HR Clerk | Male | 7yrs | No | 1st of 2 children |

| Bongi | 35 | Married | Logistic Coordinator | Female | 11yrs | No | Only child |

| Lebo | 30 | Single | Online English teacher | Female | 4yrs | ADHD | Only child |

Second, to obtain qualitative data, mothers participated in a semi-structured interview focusing on their personal experiences of raising a child with ASD. In keeping with the principles of IPA, the interview schedule was developed by exploring existing literature on the influence of ASD on families. The interview schedule was comprised of open-ended questions that were specifically designed to probe mothers’ thoughts, feelings, and parenting behaviours. Mothers were asked to describe in their own words the impact of raising a child with ASD (e.g., “Tell me about your experience as a mother caring for a child with ASD?”) on their personal lives (e.g., ” How does care for a child with ASD impact on your personal relationships?”); family life (e.g., “What is the impact of your child’s ASD on the family?”); social life (e.g., “How has autism impacted your social life?”); and psychosocial wellbeing (e.g., “How has autism impacted you emotionally and psychologically?”). Careful prompts and follow-up questions enabled the researcher to get rich details of the mothers’ experiences of raising children with ASD.

The interviews were conducted at a venue that was convenient for the participants, such as the participants’ homes or at a mutually agreed venue. To ensure quality and accuracy, we decided to conduct the interviews over the weekend to minimise potential external distractions. As a result, most of the interviews were conducted on a Saturday since it was not a working day and the mothers were able to arrange for the children to be looked after. In addition, external distractions were also controlled by selecting quiet and private venues. Interviews lasted between 45 and 90 minutes and were conducted in either English, isiZulu, SePedi, or Setswana, the languages the participants and the researcher were fluent in. The interviews were audio-recorded with the consent of each participant, transcribed verbatim, translated into English, and anonymised.

2.5. Ethics

Ethical approval to conduct the study was received from the Sefako Makgatho University Research Ethics Committee (SMUREC/M/207/2018: PG). Written permission was received from the director of the NPO to distribute the study information leaflet to the mothers at the centre. Mothers who were interested in the study contacted the researcher directly. At the interview, consent was discussed with the mothers. Mothers were informed that participation was voluntary, and they had the right to withdraw from the study at any point. Issues of confidentiality and researchers’ ethical responsibilities were also part of the conversation. They were informed that should they agree to participate, pseudonyms would be used to protect their identities in all written publications and verbal discussions. All participants provided written informed consent to participate in the study by signing the consent form. The study adhered to the guidelines and principles of the Declaration of Helsinki [29]. For preparation of this manuscript, pseudonames were used in order to conceal the true identity of the participants.

2.6. Data Analysis

The verbatim transcripts were analysed in accordance with the principles and guidelines of IPA that allowed for an inductive and iterative analytical process [28]. IPA was deemed useful and suitable since it allowed for an in-depth inductive analysis that captured the subjective meaning and revealed the distinct understanding of the mothers’ experiences of raising a child with ASD, as well as a theoretically informed perspective of the challenges attached to the experience.

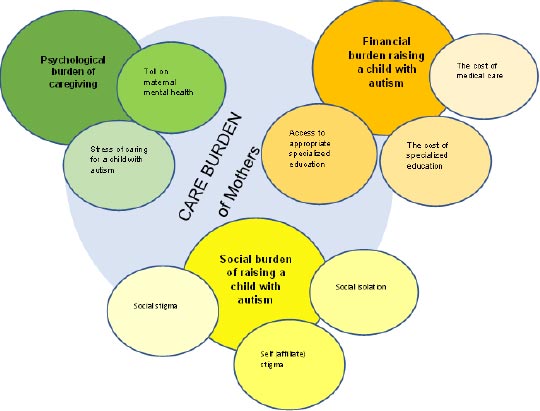

First, verbatim transcripts were loaded onto the software program NVivo 11. Next, a simultaneous listening of audio recordings and reading of each participant's transcript separately for a number of times to become immersed in the data led to noting salient observations on the participants’ thoughts and feelings in the form of comments. This ultimately generated the initial coding frame [30]. In the next step, the initial codes were evaluated for connections across each transcript and developed into descriptive, linguistic and conceptual themes. The fourth step, the emerging themes were connected, detected patterns across cases and clustered into potential superordinate themes. In a fifth step, the first and third authors reviewed the emerging themes to check if they formed a coherent pattern and if they are accurate representations of superordinate themes on the mothers’ experiences raising a child with ASD. Less central codes were removed and final structure of superordinate and subordinate was created. Findings are described as themes of all the participants (Fig. 1), supported by verbatim extracts from the mothers’ narratives.

| Superordinate Themes | Subordinate Themes |

|---|---|

| Psychological burden of caregiving | Stress of caring for a child with autism |

| - | Toll on maternal mental health |

| Financial burden raising a child with autism | The cost of medical care |

| - | The cost of specialised schooling Access to appropriate specialised education |

| Social burden of raising a child with autism | Social isolation |

| - | Self (affiliate) stigma Social stigma |

We ensured qualitative rigor by incorporating methodological procedures to ensure trustworthiness [31]. We addressed the credibility of our findings through triangulation, and written reflexive field notes. The data analysis involved multiple researchers. For example, the second author independently coded the interviews. The codes were reviewed and discussed with the first and third authors until a consensus was reached, which enhanced the analysis. Moreover, personal biases in the data analyses were reduced through ongoing reflexive discussions between all the authors. Dependability was addressed since all the authors are clinical psychologists with experience in IPA.

3. RESULTS

As seen in Table 2, three main themes were identified during the analysis that described the mothers’ burden of caring for a child with ASD. The first theme reflects the psychological impact of caring for a child with ASD. The second theme highlights the financial burden associated with caring for children with ASD, while the third theme that emerged is related to the social impact of raising a child with ASD, which is associated with isolation and exclusion from society.

3.1. Psychological Burden of Caregiving

Caring for a child with a neurodevelopmental disorder can be very strenuous, thereby leading to stress and poor psychological well-being for the caregivers. The mothers highlighted their challenges, ranging from experiencing high levels of emotional stress to more serious psychological problems associated with caring for their children with ASD.

Stress of caring for a child with autism. All mothers reported experiences of distress, including feelings of despair and feelings of being overwhelmed by the daily challenges of caregiving. Some of the mothers, like Thandiwe, reported:

“This illness [ASD] has destroyed so many things, the things that I'm going through. Just so many struggles every day.”

While Deliwe had the following to say:

“I get hurt on the inside and to the point that I fear that I might collapse, it’s just too difficult to manage this condition of my child.”

Likewise, Mamsie reported:

“I don’t have the right words to explain the magnitude of the hardness.”

Caregiving stress was also exacerbated for some mothers because of the child's having a dual or comorbid diagnosis. Apart from having to deal with the ASD diagnosis of children, they also had to deal with their child’s comorbid health problems or disability. This was particularly a major difficulty for Thandiwe:

“My child was born blind and then diagnosed with Autism. The issue with the child was not Autism only, so you go to Autism school and they say only if he was not blind, we would take him. Then you go to the school for the blind and then they say if he was only blind and not having Autism, we would take him. I don’t know which school I didn’t go to, it made me emotional.”

Similarly, Lebo indicated that apart from having to manage her child’s ASD there are additional challenges of disruptive behaviour as her child had a comorbid diagnosis of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). She said the following about her experience:

“After we found out about the diagnosis of Autism [Thato] was later diagnosed with ADHD. It’s difficult for me really because she’s just busy. She’s touching things, and I’ll be constantly running after her and I can’t relax.”

For Deliwe, her experience of caring for her child who is suffering from co-morbid seizures has made her caregiving experience especially stressful. As she said:

“On top of Autism, [Nkosi] is experiencing seizures. I remember walking on foot in the wee hours of the morning trying to get to the hospital and get help for him. The seizures can happen two times a day. I have been through a lot with this child and it hurts me…I am always stressed and worried.”

Toll on maternal mental health. All of the mothers revealed that the stress of caring for an autistic child took a toll on their mental health. For four mothers, the daily challenges and stress associated with caregiving escalated to being diagnosed with clinical depression in the past. In Ntsiki’s case, the child’s behavioural problems led to her developing and being diagnosed with depression. She said:

“I went through depression; I asked myself why I was having this difficult child. His behaviour drained me, the meltdowns. I think that’s what took me to depression.”

Similarly, Thandiwe said:

“I was depressed by the stress of raising two autistic children. I went through depression.”

For Mamsie, the constant rumination about her child’s illness eventually took a toll on her mental health. She noted:

“I’d be sitting at home and I’d be thinking about my child’s illness, I sank into depression.”

While Bongi’s self-blame for her inability to emotionally connect with her daughter eventually led to her being depressed. She said:

“I blamed myself for her behaviour to the point of developing depression. There were times when I felt I had no connection with her, and then I would try to reach out and she would shut me out. And not even want a hug.”

3.2. Financial Burden of Raising A Child with Autism

The caregivers in this study highlighted that caring for children with ASD has many financial needs, and most of the time, they cannot cover all the costs. In particular, the cost of accessing medical care and specialised education for their children with ASD were highlighted as major financial burdens for the mothers.

The cost of medical care. Eight out of the nine mothers spoke about the substantial healthcare expenses associated with the care of their autistic child. Most of the mothers struggled to cope with the cost of medical care. Thandiwe shared her experience of the high cost of medical care for her children:

“I have two autistic children; their medication is expensive. I spend around R2000 per month on both of them. It’s too much I can’t even cope.”

Moreover, seven mothers noted that they could not afford the costly medication despite having medical aid. It was not uncommon for mothers to pay for medication out-of-pocket even though they had medical aid cover. Ntsiki said:

“The medical aid is expensive and it would be exhausted within six months. I mean, there was a time when his medication would cost R500 per month and we had to pay that from my pocket.”

Likewise, Mamsie said:

“[ Sihle’s] dad is not working at the moment, so I have to pay for the medical aid. Even that comes with its own challenges. The medical aid does not cover for Autism. So, what’s the point of having medical aid, if it’s not going to cover for the illness.”

The cost of specialised schooling. Six of the mothers spoke about the costly educational expenses and expressed concern over the lack of government-funded specialised schools for children with ASD. Specialised schools for ASD were not only extremely limited but also only available as privately run schools that were situated outside the children’s’ neighbourhoods and were extremely expensive.

Ntsiki’s sentiments are that of all the mothers:

“There are no government schools for kids with Autism.”

While Lwandle expressed concern over the cost of schooling:

“We found the schools to be very expensive.”

Similarly, Lebo shared the same sentiments on the cost of schooling:

“They day care fees are expensive. I never thought in my life that I would spend more than R2000 per month on day care.”

Access to appropriate specialised education. Some mothers indicated the need for appropriate educational provision for their children. For example, Lwandle said:

“The only problem was finding the appropriate school. Because the normal day care could not handle or manage him…but there are no schools for autism children in my area…”

On the other hand, for Ntsiki, not having access to specialised education due to the costly expense meant keeping her child at home:

“One of the challenge is finding proper care for the child that specialises or has experience in caring for children with special needs. There was a time when I kept my child at home for three years because I couldn’t afford to pay for the fees...”

3.3. Social Burden of Raising A Child with Autism

Most of the mothers reported that they had experienced stigma by virtue of being parents of a child with ASD. The mothers reported that society neither accepts nor understands their children. Most of the time, people stare at their children, and as a result, they avoid social interaction and are forced to remain at home in isolation.

Social Isolation. Most of the mothers isolated themselves by not attending social events and, in some instances, excluded their children with ASD from attending social gatherings.

The negative impact on the social life of mother’s are shown:

“I don't have a social life at the moment, we don’t go anywhere with my children.”(Mamsi)

“I can’t go anywhere with him…I can’t do your normal/typical day at the mall, play games.” (Lwandile)

“When you have a child with Autism, your social life becomes non-existent because you take care of the child.” (Ntsiki)

In other instances, the mothers reported being excluded or rejected from social gatherings by others (i.e., family and friends, etc.),

“You take your child to church you are always going to be isolated because the child is going to make noise. I mean, they make noises, they flip their hands at times and they bang their heads.” (Ntsiki)

Also, some mothers sheltered their children. For example, they kept the children from attending social gatherings out of fear that they might be at risk of being harmed or taken advantage of by others (ridiculed). Mamsie reported:

“Because he cannot speak, I fear that maybe someone will snatch him because they know that he can’t speak. I wish I could build a retaining wall around him. I am scared, especially with these kidnappings and mutilations.”

Similarly, Lebo indicated:

“With us, most of the time, with black communities, we usually host our parties at home. The gate is open, there are cars driving around on the streets and some of them are very fast. So, that becomes a safety concern, that she might go out of the yard and be bumped by a car. Or, she will do something and hurt herself, because we had an incident like with her at school. Where she, before the diagnosis, where she was just running around quickly and couldn’t stop herself and she hit a swing, and she had to get surgery as a result of that.”

Self (affiliate) stigma. For most of the mothers, the self-isolation from social spaces highlighted the social pressure that they experienced as a result of internalised or self (affiliate) stigma. Several mothers reported feeling embarrassed by their children’s atypical behaviour. For instance, Bongi reported:

“At times I feel embarrassed by my child’s behaviour. We went to a party and she removed and tore down most of the balloons and other decorations. And the other children started crying because of all that, so ja it’s also frustrating.”

Thandiwe reiterated this sentiment:

“I make excuses for not attending party invites or braais. Initially, I will accept the invitation and later on create an excuse for not going. It’s difficult to be around people with my child.”

Some mothers made reference to how stressful the child’s disruptive and challenging behaviour was and how it prevented them from socially engaging with others. Deliwe reported:

“He causes a scene in public: he cries and screams, sometimes he would leave the house and roams around and we would not know where he is. At times, he goes to people’s house, people that we don’t even know. This worries me.”

While Thandiwe reported:

“He messes himself; sometimes, he would take the faeces and smear them all over the walls with his hands. He also harms himself, at times he takes a fork or spoon and insert it into his rectum, he would not stop until he sees blood and now his rectum is injured. I don’t want people to see that. It’s embarrassing.”

Externalised stigma. Some mothers reported avoiding taking their children to public places out of fear of being stigmatised by others. Four of the mothers reported having experienced ill-treatment by others and being made to feel ashamed of the child’s behaviour. Bongi reported:

“I was invited to a party and this guy didn’t know about my child’s condition. So, my child was busy jumping and making funny sounds and then he said to her ‘What are you doing? Are you crazy? You know shouting at her.”

Other mothers reported feeling judged because of their children’s autistic behaviour that people misinterpret and misattribute. Lwandle reported feeling ashamed of her child’s behaviour:

“In a taxi, especially in the taxi that’s where this whole thing would pop out. He would just scream and talk loud; I would be like…please keep quiet. And it was embarrassing that people could see that he was old but he cannot talk properly. and I felt like people were giving me that” what is wrong with your child.”

For some mothers, community members viewed or perceived the children as cursed and under attack by supernatural forces. Ntsiki reported:

“The child is labelled as crazy or is demon-possessed.”

While Bongi reported:

“Some people thought my child was possessed by some spirit.”

Similarly, Lebo indicated:

“A few people said I must take her to church to be prayed for…we should get anointing oil.”

Some mothers shared how they were more impacted the society’s perception of the child’s behaviour than the actual behaviour displayed by the child. A common perception among the parents was that others tended to judge their children as “naughty” or “crazy” children. One mother, Bongi said:

“One parent said to my child: “What are you doing? Are you crazy?” and I decided not to ever go with my child in spaces where she would be treated like that.”

Some mothers shared how people mistake the autistic behaviour for ineffective or bad parenting. For instance, Ntsiki said:

“He throws tantrums and the people are looking at you as if you are not disciplining the child.”

Similarly, Bongi indicated:

“Because I couldn’t control him. And he wouldn’t listen to me when I tell him to keep quiet. And it’s the embarrassment of gore (that) other parent around me, they see me as a bad mother that can’t discipline her child.”

The lack of understanding of the child’s behaviour by others poor treatment, and unfair social evaluations resulted in caregivers refraining from social activities to avoid social judgments.

4. DISCUSSION

The findings show how the mothers in this study make sense of their experience of caring for a child with ASD. The mothers' stories provided insight into an especially challenging caregiving experience. Using IPA, the findings of this study revealed that black African mothers in South Africa had considerable psychological, financial, and societal burdens as a result of caring for a child with ASD. Previous research has indicated that raising a child with autism is associated with a high care load [32, 33].

The study showed that the experiences of mothers caring for children with autism involved a number of stressors that were significant sources of psychological burden. Feelings of worry, frustration, despair, and being overwhelmed associated with the practice of raising a child with ASD contributed to the psychological burden that mothers experienced in this study. Consistent with existing research, the findings from this study showed that mothers experienced emotional problems, especially depression [12]. Ingersoll and colleagues showed that mothers of children with ASD endorsed significantly higher levels of depressed mood and parenting stress than mothers of children without ASD in the US [34]. Similar findings from three major cities across South Africa showed that mothers experienced significant psychological stress associated with the parenting of a child with ASD when compared to fathers [23].

Mothers in the current study attributed their depressed mood to their lack of understanding of their children’s developmental deficits and their inability to effectively manage their children’s behavioural difficulties. These findings suggest that the child’s behavioural problems have negative effects on the mothers’ psychological well-being [22]. The mothers in this study were left feeling helpless and powerless, which in turn had a negative impact on the care they provided to their children; a finding supported by Simelane [23]. Based on prior research, several factors have been shown to work in concert to increase stress in mothers of children with autism spectrum disorder, which may help to explain the vulnerability to maternal depression in this study. First, the realisation that the disorder is incurable increases maternal stress. Second, feelings of guilt and self-blame in mothers of children with ASD correlate with maternal stress and depression. Third, aspects of the child’s behaviour, specifically the difficulty and lack of control in managing associated behaviour, seem to be linked to increased maternal stress and depression [12]. Fourth, as primary caregivers of children with autism, mothers usually face a variety of problems, including heavy financial burden, discrimination, and stigma, which have been found to be associated with increases in parenting stress and depression [35]. Finally, in addition to caring for the autistic child, mothers bear the majority of the family's responsibilities, including household management, caring for the needs of other children and family members, and a variety of other caregiving duties [36]. These caregiving responsibilities have a significant impact on maternal emotional well-being.

This study showed that mothers caring for children with ASD experienced great financial burdens. Financial difficulties and a need for additional financial support for the child’s medical care, including costly specialised education expenses, emerged as the most important financial burdens in this study. Consistent with previous research, mothers in this study were exposed to out-of-pocket costs and high costs for specific treatments available only in private hospitals, as well as access to specialized schooling facilities that were only available in the private sector [36].The cost of ASD-specific care, medical and education appeared to make the financial situation of ASD families worse, especially for mothers of children with limited income who could not afford it all. This finding is consistent with existing research [16, 20], suggesting that raising a child with ASD adds additional financial strain from the high cost of medical care, specialised education, and supportive care expenses. In a previous study conducted among Chinese children with ASD, Ou and colleagues [16] found that families with ASD children carry a heavy financial burden associated with the overall care of a child with ASD. They found the financial cost of raising a child with autism compared to a neurotypical developed Chinese child to be exponentially higher. Similar findings were observed in Nigeria [24], South Africa [37], Egypt and Kenya [38]. In South Africa and other sub-Saharan countries inadequate healthcare services and lack of supportive services for children with disabilities and their families, extenuate this burden [5]. For example, children with ASD receive limited services from health or social care services within the South African public sector. Moreover, documented evidence showed there is a lack of available psychologist and psychiatrist, especially those treating ASD in most African countries, including South Africa [5]. For mothers of children with ASD, barriers in access to required medical care or supportive educational or rehabilitative public services, in the context of limited financial resources, may be major sources of stress and poor maternal mental health.

Similar to other qualitative studies conducted in sub-Saharan Africa [5], China [39], South Korea [40], and India [41], mothers in this study expressed considerable social burden. Notably, the mothers’ social burdens were expressed in relation to affiliate (internalised) and social stigma, and the impact of ASD on their social lives. Based on the current findings, mothers often internalised external criticism as internalised or affiliated stigma, resulting in feelings of self-blame, guilt, shame, embarrassment, and helplessness, believing that they have little or even no control over their children’s condition and corresponding social prejudices and discrimination. Tilahun et al. [17] conducted a study among 102 caregivers of children with ASD and intellectual disability in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia that demonstrated the pervasive nature of stigma. The research found that over 40 percent of mothers worried about being treated differently; 46 out of 102 felt embarrassed or ashamed about their child’s condition; about 27 percent felt the need to hide the child’s condition from others and made an effort to keep it secret, while close to 50 percent felt responsible or at fault for the child’s condition [17]. In addition, mothers in this study described experiences involving social stigma, a finding that is consistent with research conducted in high-income countries [9], as well as, low-and middle-income countries [42].

Consistent with previous qualitative research [9, 37], the mothers in this study experienced stigma related to the mislabelling of their children as ‘crazy’ or ‘naughty’ or ‘demon-possessed’; and were criticized for not possessing competent parenting skills to control or discipline their children when they displayed socially inappropriate behaviour in public. As a result, mothers in this study often avoided socially engaging activities to escape social judgment and minimise worry about the child’s potential behavioural outburst in public- leading to (self) isolation and loneliness that is supported in previous research [43]. According to a recent scoping review, social isolation and loneliness have negative effects on the health and well-being of mothers [44]. Studies that examined loneliness and isolation found it to be associated with parenting burnout, increased stress, and depression [43]. The findings also support the research [45] that showed mothers of children with ASD are frequently excluded or marginalised from community participation and may be particularly isolated when others are not accepting of their children. Marginalisation deprives mothers of children with ASD of accessing social support in their communities and may lead to further parenting stress and poor mental health [45]. This finding extends existing literature that shows that mothers experience stigma by association with their children and assume responsibility for their children’s stigmatic condition. This is an important finding because previous research showed that stigma is associated with poorer mental health and quality of life among mothers of children with ASD. Both self (affiliate) stigma and social stigma are associated with exacerbated psychological distress and have an adverse effect on the parenting experience since they undermine the competency of the mother to effectively parent the child with ASD [10]. Research suggests that the damaging impact of stigma on the parenting practices of mothers raising children with ASD is mediated by diminished self-esteem and self-efficacy [46]. The quality of caregiving is important in the early years of a child’s development, so it is important to address any stigma and its consequences of emotional distress and isolation among mothers of children with ASD. Because maternal emotional well-being is important to the child’s development.

CONCLUSION

This explorative study offered valuable insight into the mothers’ lived experiences of raising a black African child with autism in South Africa. Our findings showed that the burden of raising a child with ASD is a response to psychological, financial, and social stressors associated with the mothers’ parenting experiences. Maternal caregiving stress was largely described in relation to the difficulties mothers had in managing their children’s atypical development and behaviour problems and the intersecting feelings of self-blame and guilt brought on by experiences of stigma by the community towards their children’s condition. Importantly, the caregiving burden on these mothers may lead to social isolation and significant psychiatric problems in both mothers and their children. The implication is that mothers of children with autism require special attention from mental health professionals and psychosocial support during the parenting process.

IMPLICATIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

The findings suggest that healthcare professionals and social service providers should recognize that parenting responsibilities and burdens are complex, demanding, and have significant implications for the overall well-being of mothers raising children with ASD.

The challenges of raising a child with autism require interventions that are aimed at maximizing caregiver support. There is a need for psychosocial interventions with a family-centered approach that can provide mothers with the knowledge and skills pertinent to the care they are providing for their children.

Mental health practitioners must focus on tailoring psychosocial interventions that specifically aim to improve the mothers' ability to manage stressful emotions and enhance their parenting skills. Mental health practitioners may provide psychoeducation that can provide mothers with accurate knowledge to challenge stigmatised views about ASD. Community-based interventions, in the form of support groups for mothers and offered by mothers raising children with disabilities, may be a cost-effective and helpful way in which mothers can access social support.

In a low-resource setting, such as South Africa, community-based psychosocial interventions delivered by non-specialists are a viable strategy to scale up support for families with children with ASD. South African public primary health care facilities provide a viable option where psychological counsellors and community health care workers can offer non-specialist intervention to families within the community. The South African government should subsidise low-income families to access these needed services privately to ease the financial burden on families.

LIMITATIONS

There are several limitations to the present study that should be noted. First, the mothers of children diagnosed with ASD lived primarily in urban areas and were recruited through non-probability sampling procedures by a non-profit organization. In addition, the study was biased towards mothers of children with ASD from slightly higher economic backgrounds who had access to certain resources. This limits the extent to which the findings may be generalised to more rural settings and low-income families that cannot afford the cost of such needed resources. Further investigation with a cross-cultural and inter-country comparison is needed before these findings can be generalised. An investigation that aims at the whole family, including the father and the siblings, will help expand knowledge about the impact of ASD on the family in South Africa. An exploration of the parenting experience of raising a child with autism across different developmental stages would be invaluable since the caregiving burden may be influenced by various challenges across developmental and social transitions.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

A.G.L. was responsible for the study design, manuscript preparation and writing. T.M. was responsible for study design and data collection, data capturing and writing the manuscript. M.P.M. was responsible for study design, manuscript preparation and writing of the manuscript.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| ASD | = Autism spectrum disorder |

| IPA | = Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis |

| ADHD | = Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder |

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

Ethical approval to conduct the study was received from the Sefako Makgatho University Research Ethics Committee (SMUREC/M/207/2018: PG).

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

No animals were used in this research. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of institutional and/or research committee and with the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki, as revised in 2013.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Participants were made aware during the informed consent phase that this work will be published and agreed to that. It is the researchers’ responsibility to ensure that at all times the participants will be protected and all their details will be kept anonymous at all times, hence the use of pseudonames.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

The datasets that generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available as the authors do not have consent from all participants to distribute the raw data. The other reason is that, during the interview, participants' real names were used. For the preparation of this manuscript, pseudo names were used for confidentiality purposes.

STANDARDS OF REPORTING

COREQ guidelines were used.

FUNDING

Partial financial assistance was obtained from the Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences University research fund.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

There is no competing interest in this manuscript. The views expressed in this submitted article are those of the authors and not of the institutions they are affiliated with or the funder.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge the participants who took the time to share their experiences of caring for a child living with an autism spectrum disorder.