All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Investigating the Professional Commitment and its Correlation with Patient Safety Culture and Patient Identification Errors: Evidence from a Cross-Sectional Study from Nurses' Perspectives

Abstract

Introduction

Nurses' professional commitment is crucial to their qualifications, impacting patient safety. This study aims to explore the relationship between nurses' professional commitment and patient safety culture, specifically focusing on patient identification errors.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted in 2022 involving 340 nurses working in educational medical hospitals in southern Iran. Data collection instruments included questionnaires on nurses' professional commitment, patient identification errors, and patient safety culture. Descriptive and inferential statistics, such as t-tests, ANOVA, Pearson's correlation coefficient, and multiple linear regression, were performed using SPSS software version 23, with a significance level set at p = 0.05.

Results

The mean scores for professional commitment, patient safety culture, and errors in patient identification, as perceived by the nurses, were 77.64 ± 14.32 (out of 130), 2.71 ± 0.78 (out of 5), and 16.41 ± 4.58 (out of 32), respectively. There was a statistically significant correlation between professional commitment and errors in patient identification (r = -0.577, p < 0.001) as well as patient safety culture (r = 0.456, p < 0.001). Regression analysis revealed that nursing job satisfaction, understanding of nursing, self-sacrifice for the nursing profession, and engagement with the nursing profession were predictors of patient safety culture and errors in patient identification (p < 0.05).

Conclusion

Nurses' professional commitment was found to be at a moderate level. Furthermore, the dimensions of professional commitment significantly influenced patient safety culture and errors in patient identification. To enhance nurses' professional commitment, and subsequently improve patient safety culture and reduce identification errors, it is recommended to implement management mechanisms that increase job satisfaction, understanding, engagement, and professional self-sacrifice among nurses.

1. INTRODUCTION

Nurses are recognized as one of the largest professional groups in healthcare systems, playing a vital role in improving the overall health of communities [1, 2]. Professional commitment among nurses is characterized by intrinsic satisfaction with assigned responsibilities, leading to a strong willingness to continue their profession and perform their duties to the best of their abilities [3]. Committed individuals in their profession serve as a source of energy and capability, working towards the ideals and goals of their profession [4]. Conversely, a lack of commitment among human resources not only hampers progress towards goals but also contributes to indifference towards professional issues, resulting in decreased quality of performance, job turnover, and dissatisfaction [5]. Hence, professional commitment is considered one of the most influential factors determining an individual's professional behavior [6].

Professional commitment in nurses is regarded as a key professional competency [7, 8]. This commitment leads to reduced work fatigue, increased job satisfaction, career longevity, and ultimately improved quality of patient care [5, 9]. However, enhancing and increasing professional commitment among nurses has become a significant challenge for nursing managers in the present era [5, 10]. Having committed human resources with sustainable commitment is considered an indicator of organizational excellence [11]. Nurses with high levels of commitment demonstrate a better understanding of their profession, a high level of responsibility, and selflessness and sacrifice for their profession [12].

Several studies have emphasized the critical role of professional commitment in nursing, with findings suggesting that nurses with higher professional commitment have a reduced intention to leave their profession [13]. Moreover, professional commitment has been shown to have a positive impact on nurses' intent to stay in the profession, with factors such as job stability, family support, professional adaptability, and financial resources [14].

Furthermore, enhancing professional commitment has numerous beneficial consequences for both nurses and patients. These include reducing patient falls [15], improving patient safety [16, 17], increasing nurses' job satisfaction [18], promoting self-evaluation among nurses [19], fostering appropriate citizenship behavior when dealing with patients [20], and enhancing nurses' job performance [21, 22]. Another area related to nurses' professional commitment and its potential impact is accurate patient identification and adherence to patient safety culture [16, 23-25]. Proper identification of patients is a crucial step in providing safe therapeutic interventions [26]. Errors in patient identification can have serious implications, such as administering the wrong medication, performing incorrect treatment procedures, misdiagnosis, mislabeling of tissue samples, and issuing incorrect discharge instructions [27-30]. These mistakes underscore the significance of patient safety and the observance of patient safety culture.

Improving patient safety is a key priority for healthcare facilities, including hospitals, as clinical errors continue to occur worldwide, leading to substantial financial and human costs [31, 32]. Safety conditions in patient care have been found to be inadequate in some studies, emphasizing the need for improving processes and treatment protocols [33]. Establishing a patient safety culture and fostering an open reporting environment for mistakes can contribute to enhancing patient safety [34-36]. Nurses with high professional commitment are more likely to accurately report incidents and adhere to a culture of patient safety [37]. Conversely, a decline in nurses' professional commitment can negatively impact the quality of care and patient safety [16]. Furthermore, Teng's study demonstrated a positive association between nurses' professional commitment and the patient safety culture, as well as compliance with patient safety indicators [23]. Similarly, Bishop et al. reported that promoting nurses' professional commitment was linked to improved quality of patient communication, enhanced care, and increased patient safety [25].

Understanding the relationship between professional commitment, identity recognition, and patient safety culture can assist hospital managers in establishing and promoting commitment as a key goal for their staff [16]. Considering the significance of identifying factors that influence error occurrence in patient identity recognition and patient safety culture as safety indicators, along with the crucial role of nurses' professional commitment in identifying and fostering these elements, this study aimed to investigate nurses' professional commitment and its correlation with identity recognition and patient safety culture in educational, medical hospitals affiliated with the Shiraz University of Medical Sciences in southern Iran in 2022.

2. METHODS

2.1. Design and Setting

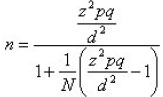

This descriptive-analytical study was conducted cross-sectionally in educational, medical hospitals affiliated with the Shiraz University of Medical Sciences in southern Iran from March to June 2022. The study population consisted of nurses working in the 10 educational medical hospitals. The total population (N) of nurses was 2,943. To determine the sample size, a 5% margin of error was considered, resulting in an estimated sample size of 340. The required sample size for each hospital was calculated by dividing 340 by 2,943 and multiplying the result by the number of nurses in each hospital. Details of the hospitals included in the study, the total frequency of nursing staff, and the sample size for each hospital are presented in Table 1.

where,

P=q=0.5

d=0.05

z= 1.96

N=2943

| Hospitals | Frequency of Nursing Staff | Sample Size |

|---|---|---|

| Namazi | 1047 | 121 |

| Shahid Faghihi | 491 | 56 |

| Hazrat Ali Asghar (AS) | 197 | 23 |

| Shahid Chamran | 264 | 30 |

| Zeinabieh | 145 | 17 |

| Khalili | 74 | 9 |

| Hafez | 117 | 14 |

| Ebn-e-Sina | 71 | 8 |

| Shahid Rajaei | 441 | 51 |

| Shahid Dastgheib | 96 | 11 |

| Total | 2943 | 340 |

In each hospital, participants were initially selected based on the number of nurses in each ward. To ensure representation from different departments, a stratified random sampling method was employed. Nurses were randomly selected using their personnel codes and a random number table. The inclusion criteria for participation in the study were a willingness to participate and current employment in various clinical wards of the hospital. Conversely, the exclusion criteria included a lack of willingness to participate and involvement in non-clinical wards, such as the administrative and financial departments of the hospital.

2.2. Instruments

The data collection tool used in this study was a four-section questionnaire. The first section included demographic information about the nurses, such as age, gender, level of education, work experience, type of employment relationship, marital status, number of shifts per month, and number of patients under their care in each shift.

The second part of the questionnaire consisted of Lachman et al.'s standard questionnaire on nurses' professional commitment, which comprised 26 items categorized into four domains: “perception of nursing” (6 items), “job satisfaction with nursing” (4 items), “engagement with the nursing profession” (6 items), and “self-sacrifice for the nursing profession” (10 items). The questionnaire was translated into Persian by Jolaee et al. (2015), and its validity and reliability were assessed [38, 39]. The validity of the questionnaire was confirmed (37, 38), and its reliability was established using the Cronbach's alpha coefficient (α = 0.74) [39]. Responses to this section were recorded on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” (score 1) to “strongly agree” (score 5). The total score range of 26-130 was used to categorize the average level of nurses' professional commitment as weak (26-52), moderate (53-78), acceptable (79-104), and highly acceptable (105-130) [40].

The third section of the questionnaire was developed by Shali et al. to collect data on the occurrence of incidents related to patient identification errors [27]. It comprised eight items, including failure to identify the patient before laboratory tests, failure to recognize the patient before imaging, administering medication without patient identification, sending the patient to the operating room without identification, sending the patient to the operating room without an identity wristband, inaccuracies in providing the patient's information to the nutrition unit and incorrect dietary regimens, failure to cross-check patient information with recorded information on blood products, and discharging the patient (infant, elderly, etc.) to the wrong family. Nurses' responses were recorded on a 4-point scale: “never” (score 1), “1-5 times” (score 2), “6-10 times” (score 3), and “more than 10 times” (score 4). The questionnaire was scored from 8 to 32, with higher scores indicating a higher occurrence of errors. The average status of patient identity identification based on error occurrence was categorized as very good (8-14), good (15-20), moderate (21-26), and poor (27-32) [28]. The validity and reliability of this questionnaire were confirmed by Shali et al., with a Cronbach's alpha coefficient of 0.81 [27].

The fourth section of the questionnaire included the standardized Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture (HSOPSC) developed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) in 2004 [41]. This section comprised 42 questions distributed across 12 domains, such as overall staff perception of safety, supervisor expectations and actions promoting safety, organizational learning, teamwork within units, open and transparent communication, feedback and communication about errors, non-punitive response to errors, staffing, hospital management support for patient safety, teamwork across hospital units, handoffs and transitions of patients, and frequency of reported events. Responses to this section were recorded on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree.” Scores were assigned based on the positive or negative connotations of the options, with higher scores indicating a more positive patient safety culture. The classification for patient safety culture and each dimension was divided into excellent (positive score >75%), acceptable (positive score between 75% and 50%), and undesirable or unacceptable (positive score <50%) [36]. This section of the questionnaire has undergone extensive validation procedures to establish its reliability and validity in assessing patient safety culture. It has been validated in Iran through various methods, including textual analysis, cognitive testing, and factor analysis [42, 43].

2.3. Procedures and Statistical Analysis

To collect the data, two researchers (ARY & PA) visited the hospitals on different days of the week, covering morning, afternoon, and night shifts. They distributed and collected the questionnaires during these visits. Ethical considerations were strictly followed, and nurses' participation in the study and completion of the questionnaire was entirely voluntary. Participation was only undertaken if the nurses were willing. The researchers explained the study's objectives, ensured the confidentiality of participants' responses, and obtained verbal consent before distributing the questionnaires. The completed questionnaires were collected on the same day. The collected data were then entered into SPSS software version 23 for analysis. Pearson's correlation coefficient was employed to examine the relationships between professional commitment, identity recognition errors, patient safety culture, and the nurses' age and work experience. T-tests were used to assess mean differences in the three main variables of the study based on gender, marital status, and level of education. ANOVA was conducted to investigate mean differences in professional commitment, identity recognition errors, and patient safety culture regarding variables such as employment type, number of shifts, and number of patients under care. Lastly, multiple linear regression was utilized to examine the simultaneous effects of different dimensions of nurses' professional commitment on identity recognition errors and patient safety culture.

3. RESULTS

The nurses’ mean age was 30.23 ± 6.46 years, and a majority of them (52.65%) were in the age group of < 30 years. Their average work experience was 7.23 ± 6.45 years, and most of them (63.82%) had < 10 years of experience. Moreover, 60.88% were female, and the rest were male. A majority of respondents had a bachelor's degree (90.59%), were project-based staff (37.36%), and had >20 shifts per month (70%). For most nurses under study, the number of patients under their care in each shift was >3 (80.59%) (Table 2).

| Variable | Category | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Age (Year) |

30< 30-40 40> |

179 117 44 |

52.65 34.41 12.94 |

| Work experience (year) | 10< 10-20 20> |

217 101 22 |

63.82 29.71 6.47 |

| Gender | Male Female |

133 207 |

39.12 60.88 |

| Marital status | Single Married |

146 194 |

42.94 57.06 |

| Level of education | Bachelors Master’s |

308 32 |

90.59 9.41 |

| Type of employment | Formal Contractual Contract-Based Project Corporate |

62 71 54 127 26 |

18.23 20.88 15.88 37.36 7.65 |

| Shifts per month | 10< 10-20 20> |

55 47 238 |

16.18 13.82 70.00 |

| Number of patients under supervision per shift | 2 3 3> |

43 23 274 |

12.65 6.76 80.59 |

| Dimensions of Professional Commitment | Range of Scores | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Understanding of nursing | 6-30 | 22.69 | 4.17 |

| Satisfaction with nursing job | 4-20 | 11.08 | 3.26 |

| Involvement in nursing profession | 6-30 | 18.39 | 3.92 |

| Sacrifice for the nursing profession | 10-50 | 25.48 | 5.38 |

| Total score of professional commitment | 26-130 | 77.64 | 14.32 |

| Errors in Patient Identification | Range of Scores | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Failure to identify the patient before performing laboratory tests | 1-4 | 2.33 | 0.35 |

| Failure to identify the patient before imaging | 1-4 | 2.26 | 0.41 |

| Giving medicine without identifying the patient | 1-4 | 2.07 | 0.19 |

| Sending the patient to the operating room before identification | 1-4 | 2.04 | 0.28 |

| Sending the patient to the operating room without an identity wristband | 1-4 | 2.69 | 0.23 |

| Inaccuracies in giving the patient's information to the nutrition unit and providing the wrong diet to the patient | 1-4 | 2.19 | 0.44 |

| Failure to check the patient's profile with the profile recorded on the blood products | 1-4 | 1.83 | 0.63 |

| Discharge of the patient (infant, elderly, etc.) to the wrong family | 1-4 | 1.09 | 0.71 |

| Total score of errors in identifying the patient's identity | 8-32 | 16.41 | 4.58 |

According to the results, the mean score of nurses' professional commitment was 77.64 ± 14.32 (out of 130), indicating a moderate level of professional commitment. Among the different dimensions of professional commitment, the highest and lowest mean scores were for the dimensions of “self-sacrifice for the nursing profession,” with a mean of 25.48 ± 5.38 (out of 50), and “job satisfaction in nursing,” with a mean of 11.08 ± 3.26 (out of 20), respectively (Table 3).

The findings of this study also showed that the mean error score in identifying the patient's identity was 16.41 ± 4.58 (out of 32), indicating that the identification of the patient was in an acceptable condition based on the number of reported errors. Among the errors of identifying the patient's identity, the most and the least errors were related to the errors of “sending the patient to the operating room without an identity wristband” and “discharging the patient (infant, elderly, etc.) to the wrong family” (Table 4).

According to the results, the mean score of the patient's safety culture was 2.71 ± 0.78 (out of 5). The total percentage of positive responses to the 12 dimensions of patient safety culture was 61.71%, negative responses were 23.03%, and neutral responses were 15.26%, indicating the acceptable status of safety culture in the studied hospitals. On the other hand, the highest score in positive responses was for the dimension of organizational learning and continuous improvement (85.69%), and the lowest score was for the dimension of sufficient personnel (29.46%) (Table 5).

| Dimensions | Positive (%) | Neutral(%) | Negative(%) |

Mean±SD (From 5) |

Condition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General understanding of the staff towards patient safety | 59.08 | 11.56 | 29.36 | 2.49 ± 0.45 | acceptable |

| Supervisor's expectations and performance to promote patient safety | 74.84 | 9.60 | 15.56 | 2.85 ± 0.24 | acceptable |

| Organizational learning and continuous improvement | 85.69 | 7.02 | 7.29 | 3.16 ± 0.36 | Excellent |

| Team work within units | 78.81 | 12.81 | 8.38 | 3.08 ± 0.41 | Excellent |

| Open and transparent communication | 66.42 | 16.44 | 17.14 | 2.67 ± 0.29 | acceptable |

| Feedback and communications on errors | 74.86 | 10.74 | 14.40 | 2.90 ± 0.38 | acceptable |

| Non-punitive responses to errors | 30.43 | 19.84 | 49.73 | 1.89 ± 0.71 | unacceptable |

| Sufficient staff | 29.46 | 20.64 | 49.90 | 1.78 ± 0.68 | unacceptable |

| hospital manager's support for patient safety | 55.05 | 21.08 | 23.87 | 2.36 ± 0.55 | acceptable |

| Teamwork among hospital units | 54.79 | 19.67 | 25.54 | 2.28 ± 0.58 | acceptable |

| How to transfer patient across wards | 63.17 | 18.88 | 17.95 | 2.61 ± 0.49 | acceptable |

| frequency of reported incidents | 67.95 | 14.91 | 17.14 | 2.73 ± 0.19 | acceptable |

| Patient safety culture (total) | 61.71 | 15.26 | 23.03 | 2.71 ± 0.78 | acceptable |

| Nurses' Professional Commitment | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Understanding of Nursing | Satisfaction with the nursing profession | Engagement with the Nursing Profession | Self-sacrifice for the Nursing Profession | Total Professional Commitment |

| Error in patient identification | r = - 0.483 P= 0.003 |

r= - 0.668 P<0.001 |

r=- 0.611 P<0.001 |

r=- 0.544 P= 0.002 |

r=- 0.577 P<0.001 |

| Patient safety culture | r= 0.449 P<0.001 |

r= 0.527 P<0.001 |

r= 0.406 P=0.004 |

r= 0.439 P= 0.001 |

r= 0.456 P<0.001 |

As the results show, there is a statistically significant correlation between professional commitment with errors in patient identification (r= -0.577 and P<0.001) and patient safety culture (r= 0.456 and P<0.001). Thus, with the improvement of professional commitment, the error in identifying the patient's identity was reduced, and the observance of patient safety culture was improved (Table 6).

The results of multiple linear regression analysis, aimed at determining the simultaneous effect of various dimensions of nurses' professional commitment on errors in patient identification and patient safety culture, reveal that the significant variables in the model, determined in order of importance using the Enter method, are job satisfaction, understanding of nursing, self-sacrifice for the nursing profession, and engagement with the nursing profession. Table 7 presents the β values for the influential variables, indicating the priority of their impact on errors in patient identification and patient safety culture. Furthermore, this test demonstrated that the coefficients of determination of the adjusted model (R2 Adjusted) for errors in patient identification and patient safety culture are 0.66 and 0.57, respectively. This indicates that 66% and 57% of the variations in the error scores for patient identification and patient safety culture can be explained by the variables in the model. The linear equations for the error scores in patient identification and patient safety culture can be elucidated by the variables in the model. These equations were obtained based on multiple regression analysis as follows:

Ya= 3.519 - 0.793X1 - 0.741X2 - 0.736X3 - 0.664X4

Yb= 2.374 + 0.718X1 + 0.692X2 + 0.675X3 + 0.634X4

where,

Ya: Error score in the identification of patients

Yb: Patient safety culture score

X1,2,3,4: Variables affecting the error in identifying the identity of patients and patient safety culture (Table 7).

According to the findings of the study, the mean score of nurses' professional commitment had a statistically significant relationship with the work experience (P=0.03). Thus, with an increase in nurses' work experience, the mean score of their professional commitment increased. Also, the mean score of nurses' professional commitment was significantly different regarding gender (P =0.002), marital status (P =0.04), and type of employment (P=0.04). As such, the mean score of professional commitment in female nurses (78.33 ± 15.26 out of 130), married (79.25 ± 15.59 out of 130), and official employment (79.78 ± 15.24 out of 130) was higher than others.

According to the findings, the mean error score in identifying the patient's identity had a significant correlation with the nurses' age (P=0.002) and work experience (P=0.01). Thus, with increasing age, the error in identifying the identity of patients increased, and on the other hand, it was more in nurses with less than 10 years of work experience than others. The mean score of error in identifying the identity of patients is also different regarding the level of education (P =0.04), type of employment (P =0.002), number of shifts (P=0.001), and number of patients under observation in each work shift (P =0.03). Accordingly, the mean score of error in identifying the identity of patients in the nurses (17.62 ± 5.03 out of 32), with bachelor's degree (16.58 ± 4.27 out of 32), with more than 20 shifts per month (17.53 ± 4.85 out of 32) and more than three patients under observation in each work shift (16.80 ± 4.78 out of 32) were more than other groups.

| Variable | Unstandardized Coefficients |

Standardized Coefficient β |

P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Std. Error | |||||

| Error in identification of patients | --- | Constant value | 3.519 | 1.201 | --- | 0.03 |

| X1 | Satisfaction with nursing job | 0.793 | 0.149 | 0.774 | <0.001 | |

| X2 | Understanding of nursing | 0.741 | 0.144 | 0.661 | <0.001 | |

| X3 | Sacrifice for nursing profession | 0.736 | 0.134 | 0.652 | 0.004 | |

| X4 | Involvement with nursing profession | 0.664 | 0.127 | 0.576 | 0.006 | |

| Patient safety culture | --- | Constant value | 2.374 | 1.119 | --- | 0.01 |

| X1 | Satisfaction with nursing | 0.718 | 0.164 | 0.777 | <0.001 | |

| X2 | Understanding of nursing | 0.692 | 0.159 | 0.746 | <0.001 | |

| X3 | Sacrifice for nursing profession | 0.675 | 0.156 | 0.724 | 0.001 | |

| X4 | involvement with the nursing profession | 0.634 | 0.151 | 0.699 | 0.003 | |

| Variables | Categories | Professional Commitment |

Errors in Patient Identification |

Patient Safety Culture | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| - | Mean±SD (From 180) |

P-Value | Mean±SD (From 120) |

P-Value | Mean±SD (From 210) |

P-Value | |

| Age | 30> | 74.98 ± 14.58 | 0.08 | 17.06 ± 4.84 | 0.002 | 2.49 ± 0.79 | - |

| - | 30-40 | 78.73 ± 14.64 | 16.02 ± 4.36 | 2.68 ± 0.74 | 0.002 | ||

| 40˂ | 79.21 ± 15.03 | 16.14 ± 4.47 | 2.96 ± 0.68 | - | |||

| Work experience | 10˃ | 75.52 ± 14.36 | 0.03 | 16.84 ± 4.77 | 0.01 | 2.56 ± 0.83 | - |

| - | 10-20 | 78.49 ± 14.88 | 16.16 ± 4.51 | 2.67 ± 0.76 | 0.001 | ||

| 20˂ | 78.91 ± 14.13 | 16.21 ± 4.46 | 2.91 ± 0.82 | - | |||

| Gender | Male | 76.95 ± 14.83 | 0.002 | 16.55 ± 4.32 | 0.10 | 2.64 ± 0.76 | 0.02 |

| Female | 78.33 ± 15.26 | 16.27 ± 4.71 | 2.78 ± 0.78 | - | |||

| Marital status | Single | 76.03 ± 14.11 | 0.04 | 16.49 ± 4.18 | 0.12 | 2.89 ± 0.74 | 0.07 |

| Married | 79.25 ± 15.59 | 16.33 ± 4.66 | 2.53 ± 0.79 | - | |||

| Level of education | Bachelors’ | 78.84 ± 15.64 | 0.11 | 16.58 ± 4.27 | 0.04 | 2.68 ± 0.71 | 0.05 |

| Master’s | 76.44 ± 14.42 | 16.24 ± 4.85 | 2.74 ± 0.83 | - | |||

| Type of employment | Formal | 79.78 ± 15.54 | 0.04 | 15.59 ± 4.24 | 0.002 | 2.84 ± 0.69 | - |

| - | Contractual | 78.81 ± 14.71 | 15.76 ± 4.47 | 2.82 ± 0.64 | |||

| Contract-Based | 76.84 ± 13.57 | 16.01 ± 4.71 | 2.79 ± 0.68 | 0.10 | |||

| Project | 77.01 ± 14.73 | 17.62 ± 5.03 | 2.45 ± 0.52 | - | |||

| Corporate | 75.74 ± 14.33 | 17.07 ± 4.63 | 2.66 ± 0.56 | ||||

| Number of shifts per month | 10˃ | 77.61 ± 14.14 | 0.19 | 15.69 ± 4.44 | 0.001 | 2.94 ± 0.79 | - |

| - | 10-20 | 78.87 ± 14.62 | 16.01 ± 4.42 | 2.81 ± 0.73 | 0.04 | ||

| 20˂ | 76.44 ± 14.42 | 17.53 ± 4.85 | 2.39 ± 0.80 | - | |||

| Number of patients under observation per work shift | 2 | 77.53 ± 14.56 | 0.07 | 16.12 ± 4.38 | 0.03 | 2.79 ± 0.74 | - |

| - | 3 | 79.46 ± 15.13 | 16.31 ± 4.52 | 2.77 ± 0.76 | 0.02 | ||

| 3˂ | 75.93 ± 14.87 | 16.80 ± 4.78 | 2.58 ± 0.79 | - | |||

Also, the mean score of patient safety culture increased significantly with increasing age (P=0.002) and work experience (P=0.001). The mean score of patient safety culture was different in terms of gender (P=0.02), number of shifts (P=0.04), and number of patients under observation in each work shift (P=0.02). Accordingly, the mean score of patient safety culture was higher in female nurses (2.78 ± 0.78 out of 5) than in male nurses. Also, this mean was higher in nurses with less than 10 shifts per month (2.94 ± 0.79 out of 5) and with two patients under observation per work shift (2.79 ± 0.74 out of 5) than in other groups (Table 8).

4. DISCUSSION

The findings of the present study showed a moderate level of the nurses’ professional commitment. According to Moradi et al. [44], the professional commitment of most of the studied nurses (70.8%) was estimated as moderate. Jolaee et al. [45] showed the professional commitment of nurses at a high level. In Rafiee's study [40], the nurses had a moderate level of professional commitment. In Lu et al.'s study, the nurses’ level of professional commitment in Taiwan was high [46]. Shali et al. reported that the professional commitment score was also higher than the average [15]. Geraminejad et al. [47] revealed a high level of professional commitment among nurses. In Nogueras et al.’s study, 84% of nurses showed a high level of professional commitment [48]. In Karimi et al.'s study, nurses' professional commitment was above average [49]. Al-Hamda also reported the professional commitment of nurses working in private and public centers of educational and therapeutic hospitals in Jordan at an average level [17]. The inconsistencies in the level of professional commitment of nurses in different studies might have been caused by factors such as satisfaction, religious beliefs, conscience, ethics, culture, sense of belonging, economic status, personality traits, level of education, working hours, working environment conditions, and number of personnel [50, 51]. Regarding the average level of professional commitment among the nurses in this study, we can refer to the role of nursing in the procedure of applying theoretical content in the clinical field, gaining clinical experience, and professional growth, as well as ensuring the quality of nursing care for patients [52]. According to the American Nurses Association, graduates should be ready to perform their duties due to rapid changes in the health system and the market [53]. Moreover, the American National Union of Nurses suggests that changes in health service delivery systems and market demand, as well as reforms in professional nurse education, are of paramount importance [54].

According to the findings, the nurses’ errors in identifying the patient's identity were evaluated to be acceptable. In Shali et al.’s study, the mean occurrence of errors in identifying the patient's identity by nurses was evaluated as low [15]. The findings of a study in the United States of America indicated the occurrence of errors such as 24 surgeries on a wrong patient due to the lack of accurate identification of patients, 67 surgeries performed on the wrong body organ of patients, and 16 use of the wrong surgical method for the patient [55]. In another study conducted using the self-report method over one year on NICU patients, the risk of error in identifying the identity of hospitalized patients was estimated to range from 20.6 to 72.9%, and There also were 132 cases of errors in laboratory tests of patients due to errors in the identification of patients because of errors in labeling patient samples, errors in sending patient information electronically to the laboratory unit, and taking samples from wrong patients [56].

The highest mean error in identifying the patient's identity was related to “sending the patient to the operating room without an identity wristband.” Shali et al. also reported sending the patients without identification and identity wristbands as one of the factors causing errors in the identification of the patients [15]. Bartlovas's study showed that the most common type of prevention for incorrect surgery was patient identification in the operating room using medical documentation. Moreover, in the present study, more than 90% of nurses reported that they used identity wristbands for all patients [57]. Cengiz et al.'s study in Turkey showed that the lack of information about the importance of identity wristbands among patients and the lack of knowledge of the medical staff about when, where, and by whom the patient's identity wristbands should be used were the weaknesses of hospitals [58]. In their study, Smith et al. concluded that wristbands are not fully used for patient identification [59]. This finding in the present study indicating not using wristbands, the lack of use of information technologies in the admission of the patient in the operating room [59, 60], and the average professional commitment of the nurses were the cases of sending patients to the operating room without identification wristbands are [27].

The findings of the present study also indicated the acceptable level of compliance with the patient safety culture from the nurses' viewpoint. Assessing the patient safety culture is the beginning of creating a safety culture in the hospital because it helps medical centers in determining their strategies and educational planning [61]. In line with our findings, Rafiee [40], Ebadi Fard Azar et al. [62], Amiran et al. [63], Pourshareiati and Amrollahi [64], Almasi et al. [64], and Afshari et al. [65], reported that the hospitals’ safety culture were at the medium level. Accordingly, in the existing culture governing hospitals, it is necessary to design interventions to nurture the culture according to the characteristics of each hospital and geographical location [65].

Among the components of patient safety culture, the highest mean score was for organizational learning and continuous improvement. In Afshari et al.'s study, the evaluated hospital was at a high level in terms of organizational learning and continuous improvement [66]. Consistent with the results of the present study, Pourshareiati and Amrollahi [64], Ebadi Fard Azar et al. [62], El-Jardali et al. [67], Alahmadi [68] also found the highest mean score for organizational learning. In Amiran et al.'s study, unlike the findings of the present study, the lowest mean score was for organizational learning [63]. The high mean score of organizational learning indicates the continuation of implementing learning programs and continuous improvement of security in the hospital [64]. Accordingly, individual and organizational learning, gaining experience from errors, and sharing these experiences with other colleagues are among the methods effective in improving patient safety. This requires appropriate leadership in the care team and the existence of a culture to facilitate the processes. In an organization whose employees are blamed for their errors and mistakes, mistakes happen and are not revealed, and as a result, no one learns anything, and the process is not improved [63].

Among the components of patient safety culture, the lowest mean score was for adequate personnel. In Pourshareiati and Amrollahi’s study, the component of staff issues obtained a weak score [64]. In a similar vein, Chen et al. [69] and Al-Ahmadi [68] showed that staff issues were one of the weakest components, which can be caused by insufficient nursing staff to perform work on the patient's bed, which increases the possibility of errors. Since employees are known as the predictors of patient safety, it seems necessary to have a strong and motivated workforce, which is one of the main challenges facing hospitals [70].

The findings of the present study indicated a significant reverse correlation between the professional commitment of nurses and errors in identifying the patient's identity. Moreover, there was a statistically significant direct (positive) correlation between nurses' professional commitment and patient safety culture. According to Rafiee, there was a significant relationship between the patient safety culture and the professional commitment of the nursing staff, so the higher the professional commitment of the nursing staff, the more improved the patient safety [40]. In Nehrir et al.'s study, people with a high level of professional commitment have more favorable professional ethics, and their personal performance in patient care increases compared to others [71]. Teng, et al.'s study, entitled “Professional Commitment, Patient Safety, and Patient‐Perceived Care Quality” in Taiwan also showed that the nurses with a lower level of professional commitment had a higher percentage of errors in a long study period and that the patient's safety was not also acceptable [16]. Jolaee et al. examined the relationship between professional commitment and the occurrence of medication errors, which is one of the effective dimensions. Regarding the level of patient safety, they did not report a significant statistical difference between professional commitment and medication errors. The necessity of training nurses, on the one hand, and establishing accurate error reporting and recording systems, on the other hand, can prevent and reduce the complications of errors to a large extent and consequently improve the safety of patients in the health service delivery system [45]. In their study, Bishop et al. reported that improving nurses’ professional commitment is associated with improving the quality of communication with patients and better and safer care of patients, and increasing professional commitment also increases the quality of providing safe services to patients [25]. Jabari et al.'s study showed a significant and direct relationship between nurses' professional behavior and patient safety culture [72].

According to the multiple linear regression results, the dimensions of nurses' professional commitment, including job satisfaction, perception of nursing, self-sacrifice for the nursing profession, and involvement with the nursing profession, were the predictors of errors in identifying the patients’ identity and observing the safety culture of patients. The linear regression results of Rafiee's study revealed a significant relationship between different dimensions of professional commitment and patient safety culture [40]. In his study in Canada, Graham concluded that a decrease in nurses' job satisfaction could be the main reason for an increase in patient mortality [51]. Obviously, an increase in mortality is one of the main reasons for the low level of patient safety culture in medical centers [73]. Regarding self-sacrifice for the nursing profession in predicting the patient safety culture, it should be acknowledged that nurses, considering the nature of their field and the humanities and professional ethics training they received during their education and service period, always fight against difficulties and spare efforts to save human lives [40].

The findings of the present study also indicated a direct correlation between professional commitment and nurses' work experience; as such, with increasing work experience, nurses' professional commitment increases. Also, the mean score of nurses' professional commitment was significantly different in terms of gender, marital status, and type of employment. In this regard, the mean score of professional commitment was higher in female nurses compared to males, married than single, and nurses with official employment relationships compared to other employment relationships. In Shohani et al.'s study, there was no significant relationship between demographic findings, including age, gender, employment status, and employment type with professional commitment [74]. Yoder et al. reported a significant relationship between age, background, and work experience with professional commitment [75]. Another study also found no significant relationship between work experience and nurses' awareness of ethical issues [76]. Moradi et al. concluded a statistically significant relationship between age and gender with the level of professional commitment in nurses, so the average level of professional commitment in women was higher than that of men, and the level of professional commitment in nursing staff increased with age. However, no statistically significant relationship was observed between work experience, marital status, employment status, shift work, and the level of professional commitment among nurses [44]. Khoshab et al.'s study revealed no significant correlation between empathy and professional commit- ment and demographic variables such as age, gender, and level of education [77]. Similarly, Soltani et al. reported no relationship between professional commitment and age, gender, job satisfaction, and job performance [78]. In Nogueras's study, with increasing age, work history, work experience and education level, the nurses’ level of professional commitment increased significantly. How- ever, there was no significant relationship between gender and the level of professional commitment [48]. Regarding the correlation between work experience and the level of professional commitment of nurses, it can be acknowledged that increasing work experience can help to increase nurses' understanding of various aspects of professional commitment and make them more professional in their profession.

According to the findings of this study, an error in identifying the patient's identity had a positive correlation with age and a negative correlation with work experience. The mean error score in identifying the identity of patients was also different regarding the level of education, type of employment, number of shifts, and the number of patients under observation in each work shift. In this regard, the mean error score in identifying the patients’ identity was higher in project-oriented nurses than in other employment types and in nurses with a bachelor's degree than a master's degree. Moreover, with an increase in the number of nurses' shifts per month, and the number of patients under observation in each work shift, the errors in identifying the patients’ identity increased. Seynaeve and Jorens showed that most medication errors occurred in the evening and night shifts due to a decrease in the number of nurses and an increase in their workload [79]. According to Julaee et al., there was a significant relationship between nurses' medication errors and their working conditions [80]. According to Zoladl et al., the rate of procedure and operation errors in the age group of 36 years and older, male nurses, married nurses, and nurses with management experience, was higher than in other nurses [81]. According to the present study, the average number of errors increased with increasing age, which can be a reason for the difficulty of nursing work and physical fatigue caused by patient care measures. Shams et al. determined a significant direct relationship between errors and the nurses’ age [82] Tang et al.'s study showed that with increasing age, the number of nurses’ errors decreases, which is contrary to the findings of this study [83]. Taheri et al. reported no significant relationship between age and errors, indicating that age did not play a role in the occurrence of nursing errors [84].

In Zoladl et al.'s study, the incidence of procedural and operational errors based on the employment type was significant, and the mean score of procedural and operational errors in permanent personnel was higher than in contractual personnel. Contractual personnel were higher than corporate-based personnel, and contractual personnel were higher than project-based personnel [81]. In a study conducted by Matin et al., there was a significant relationship between employment status and errors, as the errors were more frequent in permanent nurses, which is not consistent with the findings of this study [85]. However, in Sadat Yousefi et al.’s study, the relationship between the number of errors and the employment relationship was not significant [86]. It can be concluded that the type of employment, along with other causes, affects the rate of errors, and in general, by ensuring employment, the number of errors decreases.

Finally, the mean score of patient safety culture increased with increasing age and work experience. Moreover, the mean score of patient safety culture was higher in female nurses than in male nurses. Furthermore, compliance with the patient safety culture decreased with an increase in the number of nurses' shifts per month, and the number of patients under observation in each work shift. Almasi et al. also showed that the total score of safety culture among employees had no significant statistical relationship with gender; however, there was a positive correlation between work history and the total score of patient safety culture. Moreover, the employees’ safety culture had no significant statistical relationship with the type of education. However, employees with diplomas had higher scores than general practitioners and those with associate degrees and bachelor’s degrees [65]. Arab et al. reported that personnel with work experience of 6-10 years obtained the best score for patient safety culture [87]. Izadi et al.’s study, personnel with 1-5 years of work experience obtained the lowest score of patient safety culture. Regarding the level of education, nurses and midwives are more aware of patient safety culture than the secretaries of the wards and assistants [88]. According to Pourshareiati and Amrollahi, there was a significant relationship between the nurses’ gender and the level of patient safety culture. Moreover, there was a significant relationship between work history and the patient's safety culture status [64].

The limitations of this study are the cross-sectional survey, the collection of self-reported information that may have had an effect on the nurses’ reports, the use of a questionnaire, and the non-generalizability of the findings to other societies and cultures. Accordingly, interventional, qualitative, and longitudinal studies with larger sample sizes in research settings with different cultures and in other hospitals are recommended. It is also recommended that the frame of this study be considered in order to do further research on other health professions such as physicians, physical therapists, paramedics, and pharmacists.

CONCLUSION

It is important to improve the professional commitment of nurses in the studied hospitals in different aspects by using different policy and management mechanisms to promote nurses’ satisfaction. The mechanisms include improving the working conditions and environment, increasing various motivational mechanisms, matching the number of nurses and the number of patients under the supervision of each nurse to increase mutual understanding, engagement, and professional dedication of nurses, and enhancing the management skills of nursing managers such as reinforcing and improving communication among nurses, reinforcing communication between patients and nurses, and holding training courses according to the nurses’ needs. It is also necessary to use new information technologies to improve patient identification errors, promote the safety culture of the studied hospitals, establish a suitable organizational environment by improving nurses’ professional commitment to prevent fear of providing error reports, and consider appropriate incentive mechanisms for self-reporting errors and fostering a proper culture of patient safety.

ABBREVIATIONS

| HSOPSC | = Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture |

| AHRQ | = Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality |

ETHICAL STATEMENT

This study is approved by the Shiraz University of Medical Sciences Ethics Committee with the ID number of IR.SUMS.REC.1397.163.

Also, the Helsinki Declaration has been followed for involving human subjects in the study.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

All the data is presented as a part of tables or figures. Additional data can be requested from the corresponding author [S.B].

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was extracted from a research project approved by the Shiraz University of Medical Sciences (ID: 97-01-62-18812). The researchers would like to thank the respected managers of the investigated hospitals as well as the nurses participating in the study whose care and spiritual assistance made this research possible.