All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

A Systematic Review of the History of Judo in South Africa: Implication for the Future

Abstract

Introduction

There is a wide gap in judo participation between developing and developed countries. In South Africa (SA), there are only 2139 (0.00004% of the population) registered judokas compared to 122 000 (0,001% of the population) in Japan. This may be attributed to the fact that in developing countries such as SA, judo participation is dominated by a single race, generally the white race.

Methods

This disjuncture is said to be informed by a combination of factors, including affordability, preferences, and the legacy of apartheid. Interestingly, despite being a popular sport amongst the white population in SA, judo is practiced by more black people than whites in some provinces, namely, the Eastern and Western Cape. The purpose of the research is to reflect on how judo has navigated, and migrated to its current form and what the future holds. A substantial literature search was done using PubMed, SCOPUS, SportDiscuss, Google Scholar, and Web of Science (2001 - June 2020). The synthesis of the literature suggests that the management of judo requires more than just financial resources; it also needs a well-defined organizational strategy.

Results

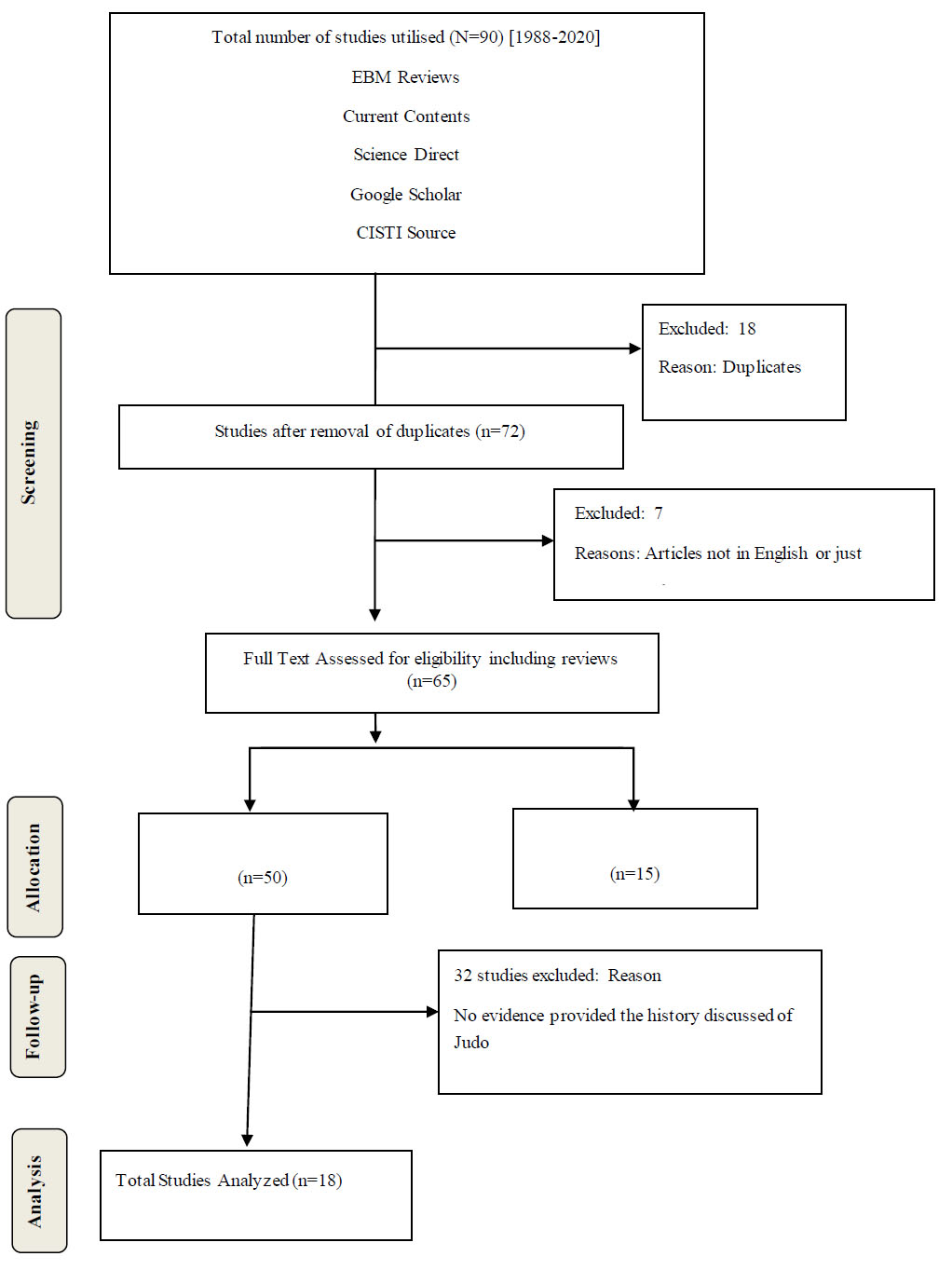

This study used 65 full-text English-language papers from 90 citations found through electronic searches. After removing duplicates and reviewing the full-text versions, 18 articles remained central to athlete success in the professionalization of federations. Federations that are run on a voluntary basis are seen as inefficient and unsustainable to successfully plan an athlete’s international success pathway.

Conclusion

Furthermore, there is a consensus amongst researcher’s that professionalism and commercialization are central to improving athlete’s performance, participation, and efficacy in the athlete’s management system. Evidently, financial resources, a clear long-term plan and full-time coaching and administration staff play a critical role in the successful management of any Federation.

1. INTRODUCTION

Judo is practiced in over 200 countries globally and is one of the most widespread Olympic sports in history [1]. Judo is a sport where one practices methods of offense and defense in randori (fighting) and kata (demonstration); it uses judo as physical education and for the benefit of society [2]. The aim of Judo is to throw your opponent to the ground and pin them down in a controlled manner [1]. This act requires a high level of skill and tactical prudence [3]. When judokas are fighting, they need a variety of complex and energy-demanding paradigm shifts to succeed. A study corroborates Henry’s definition and further points out that success is through the usage of both the strength of the mind and body, which he termed in Japanese as “Seiryoku Zenyo” in English, meaning maximum efficient use of energy [2].

In South Africa, judo is considered a non-priority sport and receives limited sport grants from the Department of Arts, Culture and Sport [4]. As a result, Judo South Africa (JSA) struggles to attract sponsorships, making it very challenging for the federation to sufficiently fund athletes who are selected to participate internationally. Furthermore, despite the South African population of more than 59 million, only 2138 judokas and technical officials are registered as members of JSA, as reflected in its information management system [5]. This is largely due to historical racial inequalities in Judo, which resulted from apartheid [6]. In that respect, Judo was practiced in separate communities and locations based on race and color in line with apartheid legislation, which dictated the laws of South Africa [6]. Carter & May [7], indicate that the survey they conducted in 1993 on one of the first national representative households found that half of all South Africans, particularly blacks, lived in poverty [7]. Mobilization of resources to support judokas is paramount and has been proven to be the key to the success of judokas [8]. In this respect, South Africa’s Inter-Ministerial Committee on Poverty and inequality, amongst others, established that Human Development Index (HDI) for black South Africans ranked between the DHI of Swaziland and Lesotho while that of white South Africans was between the HDI of Italy and Israel. When South Africa became a democratic country in 1994, all races were deemed equal before the law and could enjoy equal chances and opportunities to practice judo at locations and clubs of their choice [9]. Regrettably, reports indicate that the legacy of apartheid continues to undermine government sports development efforts [10].

Apartheid strategy worked against racial integration, which ensured separate determination and legally entrenched discrimination [11]. Post-apartheid, beyond 1994, the South African government realized the inequalities that still existed and introduced intervention strategies, inter alia, sports development plans and empowerment programmes for marginalized and impoverished communities [12]. Sports policies are meant to help sports organizations manage their sports business productively, aiming at ensuring that sport empowers and enhances peoples’ wellness [13]. These are facilitated within a structured policy framework, namely, tournament, referee, coaching and education, grading, and financial policy [14]. In South Africa, it is challenging to effectively implement sport development plans and policies as sports administrators work on a voluntary basis [15]. This voluntary context poses challenges as the demand for massification of sport and support for high performance continues to increase [15].

The fundamental challenge with volunteering arrangements is the time and availability volunteers have to provide the needed service [16]. Sam [17] argues in favor of modernization of national sports bodies to address efficacy challenges, ensuring sound governance, better recruitment of members, and full utilization of presented sponsorship opportunities [16]. Furthermore, national sports bodies are managed and equipped with qualified individuals with the purpose of helping communities build a better social capital for the betterment of regional and national sports [16]. Minikin [18] corroborates Sam’s [17] ideas on the notion of modernizing sport as a key to ensuring efficacy and improved governance. The involvement of athletes in decision-making processes ensures improved quality of decision making and legitimacy. Minikin [18] further argues that sports organizations should establish an athlete commission to ensure that athletes, as major stakeholders, participate in the affairs of sport. Carter & May [7] argue that International Olympic Committee’s (IOC) athlete commissions are not independent as they are not sufficiently involved in the decision-making within IOC bodies.

2. METHODOLOGY

2.1. Search Strategy

A literature search was conducted on five electronic databases, namely, Google Scholar, PubMed, SCOPUS, SportDiscuss and Web of Science. Literature was reviewed from 2001 to June 2020 through JSA policy documents, documentary reviews, JSA notices to members and International Judo Federation open access website, www.ijf.org. MeSH headings were not used to influence the magnitude of the research. The literature search, however, was limited to articles published in English.

The initial search included publications from 2001 to June 2020. All references retrieved throughout the search were uploaded to a shared Endnote library. Two independent authors executed the search, elimination of duplicates, examination of titles and abstracts, and screening of the full texts. Any conflicts of opinion that surfaced during the analysis were forwarded to another author for resolution. The entire versions of the studies were then reviewed, and those that did not fit the inclusion criteria were excluded.

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

The search for the articles was conducted while taking into consideration the following inclusion criteria: (a) randomized and nonrandomized controlled trials, (b) available in the English language published journal studies or those that were published ahead of print were considered for this review, (c) articles specific to Judo history and judo training methods/protocols, (d) comparisons between individual/groups' national and international global recognition, (e) participation of both sexes and (f) athletes aged 18 years and older. The only studies included were those where Judo was practiced as a sport [19].

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

The following conditions were used to filter out articles from the search: (a) articles that investigated nutritional and pathological issues; (b) articles without a Judo reference; (c) articles that did not intervene or use Judo Sport as a training protocol; (d) articles without an English translation; (e) articles that used a pharmacological substance; and (f) articles that used nutritional supplementation.

flow diagram (Gurevitch et al. 2019).

2.4. Data Extraction and Synthesis

Tables were used to outline critical information on the included studies (Microsoft Word 2013, Microsoft, London, UK), and a narrative description was used to examine the included literature on the topic. Some of the studies in the table were given in narrative form, while others employed symbols that were explained in a legend, which offered information about a specific study that went beyond the tabular explanation narrated in the results section. The data gathered from the included publications addresses the influence of historical characteristics of judo and how they can, in turn, affect sports performance nationally and internationally.

2.5. Risk of Bias Assessment

The risk of bias was assessed using the Downs and Black checklist for quantitative research [20] and the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Appraisal Checklist for qualitative research [21], which evaluated the quality of original research articles included in the current review. The Downs and Black checklist consists of 27 'yes' or 'no' questions divided into five domains (Reporting, External Validity, Internal Validity—bias, Internal Validity— confounding, Power). The JBI Appraisal Checklist for Qualitative Research, on the other hand, consists of ten items with four alternative answers (Yes/No/Unclear/Not Applicable). For the included publications, two independent researchers completed the Downs and Black checklist [20] and the JBI for results standardization (Fig. 1).

3. RESULTS

The search yielded eighteen articles published between 2001 and 2022. The majority of the articles (three) emanated from South Africa, closely followed by the United States of America, Brazil, Spain and Japan, with two articles each. England, New Zealand, Britain, Australia, Canada, Turkey, Iran, and the United Kingdom produced one article each.

Seven studies were qualitative research sampling (two were purposeful sampling); two were mixed methods; two were databases; two were surveys; one was quantitative purposeful sampling; one was a comparative study; one was phenomenological; one was Science Citation Index and Social Science Citation Index; one was cross-sectional; and one was a case study.

Most authors focused on the history of judo and how it relates to various country’s strategies to improve the athlete’s performance internationally and women's participation in judo [22]. Interestingly, only South African authors Nolte and Burnett, reflected on South African judo in their comparative studies of the national federations, British Judo Association, JSA, and Judo Netherlands. Another study reflects on the current state of judo, highlighting the lack of popularity of judo in comparison to other sports, resulting in difficulties for judo to mobilize sponsorships. Whitley et al. [12] argue for an in-depth understanding of the socio-economic problems, cultures, and political matters contributing to sports challenges. Sam [17] suggests that in recognition of the judo unpopularity and related challenges, the sport should be taken to the next level through commercialization to enhance sponsorship opportunities. As evidenced by the body of knowledge, there is a consensus amongst a few authors that professionalism and commercialization are central to improving athlete’s performance, participation, and efficacy in athlete’s management systems [19] (Table 1).

| Article/Refs. | Objectives | Key Findings | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Turgut et al. (2020) [25] |

To present the successes of Turkish Judo Federation in senior Categories in the Olympic Games. | Despite decreased medals at international events, popularity increased. | |||

|

Nolte and Burnett (2020) [15] |

To reflect on the comparative analysis of the management of national elite judo systems between three nations, Judo bond, Nederland, British Judo Association and Judo South Africa. | Best practice in terms of management of elite sports systems is suggested to be adopted as a shift towards gradual specialization and long-term strategy. | |||

|

Callan (2018) [1] |

To showcase judo as a sport and way of life. | Judo is practiced globally by more than 200 countries and five continents. | |||

|

Nolte (2018) [26] |

To deeply reflect on the management of judo organizations and elite athletes at global events focusing on three nations. | The three nations used different elite and management systems. Adoption of full-time staff and coaching leading to professionalization and efficiency. | |||

|

Noudehi et al. (2017) [30] |

To test the management of allocated resources as it relates to optimal management of elite judo system within the SPLISS model | Optimal utilization of diverse resource allocation ensures successful performance pathways within a given sport system. | |||

| Demacena et al. (2017) [16] | To investigate what motivates people to play a particular sport, particularly judo. | Brazilians understand that martial arts positively influence, inter alia, self-image, mental health, and character | |||

|

Torres-Louque et al. (2016) [33] |

To test scientific literature on the physiological outlook of judokas’ maintenance of their weight loss or gain, and related anthropometrics. | Intense exercise training and energy loss leading to a reduction of weight before a competition negatively affects the physiology and psychology of judokas. | |||

|

Mazzei (2015) [13] |

To investigate and identify organizational factors that influence international judo success. | A sum of 878 textual components arose out of categorization process and emerging from those textual portions were arranged further into 44 sub-categories, which were viewed as organizational factors which influence international success in judo. | |||

|

Peset et al. (2013) [23] |

To analyze the generation of scientific judo material and its impact on judo. | Judo has a lower profile than other sports; however, judo has raised research interest in many research and science fields. | |||

|

Miarka (2011) [22] |

To reflect on the participation of women in judo in Japan given their historic non-participation. | Women in judo across the world are treated the same and given the same status as men judokas. | |||

|

Shishida (2010) [2] |

To explain the origins of Kano’s concept with respect to judo techniques performed from afar and to reflect its realization by Kenji Tomiki through main chronicled information. | Tomiki managed to integrate judo fighting (randori) and attacks to the body (Atemi) into a set of principles using judo basics. | |||

|

Sam (2009) [17] |

To propose that sport’s development manifest the attributes often aligned to wicket policy complications and to reflect on the challenges experienced in the partnership between the government and national sports federations | Corporate sponsorship and commercialization of sport are seen to take sport to the next level | |||

|

Thibault et al. (2010) [28] |

To indicate and discuss the expanding role of elite athletes in the development of policies in global sport organization. | Participation of elite athletes in international organization has increased in recent years; however, their impact is not yet known. | |||

|

Bennett (2009) [6] |

To evaluate and explore changes in the art of judo globally. | Judo has evolved over the years to align with world innovation and modernization. | |||

|

Bernard and Busse (2004) [8] |

To examine the country’s determinants of success at the Olympic level and how many a country is expected to win. | It is not only the country’s GDP that determines the number of medals a country wins at the Olympic Games, but athletes’ talent is also a factor and the hosting advantage. | |||

|

Carter and May (2001) [7] |

To evaluate and archive the level of poverty during apartheid and whether democracy and freedom moved people out of poverty. | The study found that, between 1993 and 1998, poverty levels increased from 27% to 43% (black household – KZN) freedom. |

4. DISCUSSION

This review reflects on the past, current, and envisaged future of judo. Gucciardi [24], proposed that a combination of sports science and medicine staff is critical in the examination, identification, and management of psychological, physiological, and social factors that are critical to athletes’ performance and well-being [25]. In the context of JSA, there are limited sports science resources and support for athletes due to capacity problems and volunteer practice of coaches and judokas, among others. As a result, coaches and judokas are inadequately socialized in physiological reactions to competition and psychological adjustments to their training with a view to structuring their fit-for-for-purpose training schedules [26]. Damaceno et al. [16] list these gains as self-image, mental health, and character. Concurrently, barriers such as time, resources, family support, and availability of training venues can occur [23, 25]. In this regard, lived experiences provide a better context to deeply understand what coaches feel about sports programs and the general feeling on the ground [26].

In addition to the limited sports science resources and support, the literature indicates that Judo has been faced with gender inequality. Shishiba et al. [2] reported a strained history of women judokas in Japan largely due to the past Japanese traditional and authoritative approaches to women in general. On the contrary, Miarka et al. [22] advise that women across the globe enjoy an equal status as men judokas. The contradicting views of the two authors can be associated with a tradition initiated by Professor Kano, the founder of judo, who prohibited women from participating in judo, a position which was not favored by European countries. In the final analysis, Japan opened for women judokas, and they now enjoy equal status with men judokas. Interestingly, in South Africa, there are no reports on gender-based barriers to participating in judo, but we still observe a gender gap, with a much lower number of women participating in competitive judo compared to men. For example, only three women in JSA, Ms. Tania Tallie, Ms. Henriette Moller and Ms. Michaela Whitebooi, ever participated at the Olympic Games, 2000 Sydney and 2004 Athens Olympics, and Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games, respectively [27]. Interestingly, there is more involvement of women in various commissions in the structure of JSA [5]. However, there are only two women in the national executive committee of JSA, a matter that is being recognized and is committed to being addressed. Thus, although not well reported, it is plausible to think that gender plays a role in participation in competitive judo [10, 27].

In an effort to bridge the gender gap and entice more young people to participate in Judo, the International Judo Federation (IJF) established gender and equality, athletes, and judo for children commissions, which stand for co-operation, values, and building a respectful society, respectively [27]. The framework for IJF shows great promise on paper; however, reports on the monitoring and evaluation of how these commissions have performed are sparse. Nonetheless, researchers have outlined some recommendations [8, 20]. Damacena et al. [16], in support of IJF endeavors, contend that enticement of athletes through ranking homologation, and quality of coaches help with retention of athletes. In addition, as Thibault et al. [28] suggest, the inclusion of athletes in policy decision-making ensures the legitimacy of decisions taken by international bodies [29]. In recent years, Judo has continued to grow in popularity [29]. As a result, the sport has sparked research interest among social and natural scientists alike [29].

In streamlining the research interest, Moreno et al. [29] state that modern technology provides fortuity and complexity to researchers and to mitigate this position, an ethical framework was developed to guide researchers. The framework ensures that decision making processes by researchers in respect of consent are informed [29]. In aligning with research praxis, JSA would explore further research on the suitability of coaching programs and elite sports systems [25, 30]. JSA is not the only federation struggling with the athlete’s performance at the international level [15]. To that effect, as reported by Noudehi et al. [30], the Iranian Judo Federation, since its inception in 1975, has not performed well at international competitions. The Iranian Judo Federation’s performance resulted in the judoka discontinuing playing the sport and failure to recruit new judo members [5]. JSA, as alluded to in the introduction, suffers a similar fate and struggles to increase participation and membership numbers [15]. Post-apartheid (beyond 1994), this situation should not be the case; however, Carter & May [7] proclaim that South Africa’s democratically elected government inherited a system premised on deep inequalities characterized by basic needs (food and water) as well as poor standards of living. More research in this area is needed; poor socio-economic conditions could be a barrier to participation in sports [23]. Despite historic challenges, coaches from formerly disadvantaged areas are constitutionally allowed to open clubs in areas previously restricted to do so [21]. However, participation in sports remains a continuous problem and is exacerbated by, amongst others, the lack of government funding for sports development and turning the situation would require professionalization and commercialization of sports organizations [5]. Similar to Sam’s assertion, Bernard & Busse [8] argued that the gross domestic product (GDP) of a country contributes 1.8% of the medal tally and is a reliable determinant of international performance, particularly the Olympic Games. Johnson & Ali [31] corroborate the ideas of Bernard & Busse [8], which shows that a growth of GDP by 11% per capital increases the Olympic medal tally [30, 25]. In the realization of commercialization, professionalization and growing GDP, Nolte [26] still contends that all will efficiently work if human resource management is addressed, suggesting an adoption of full-time staffing and coaching models at all levels of federation management.

Nolte further asserts that professionalization and commercialization are best practices in the management of elite sport systems aimed at specialization and long-term strategy to improve athletic performance [26]. Professionalization and commercialization of judo will assist JSA to function efficiently and be able to adequately provide significant contributions in the field of sports science research [26]. The body of knowledge, as articulated by researchers, indicates a need for a more professionalized approach to managing federations, athlete development and a clear strategy [21]. To that effect, JSA executive members, technical officials and coaches would be more effective if they run their federation on a full-time basis to appreciate globalized trends. In that respect, consideration for full-time coaches in existing high-performance areas would enhance the federation’s capabilities for sustainable athletes’ development pathways [26]. Moreover, the current volunteering coaching and administration approach will yield ineffective coaching and management systems since federation. In sustaining achieved objectives, Thibault et al. [28] reveal that such gains identified and socialized with sports participants to entice commitment and continuity.

There are numerous tools federations could be using to sustain a developmental trajectory; the Sports Policy Factors Leading to International Sporting Success (SPLISS) model provides an insight into how effective policy interventions could help federations, leading to international competitiveness in all spheres of governance and operations [32]. Suggested interventions to improve the management of federations depend on elected officials for implementation and concern exists as to whether elected representatives in federations place organizations’ interests before theirs. Minikin [18] argues that, in most instances, elected representatives place their selfish interests before that of the organization. It is, therefore, critical to ensure the election of credible and committed executive committee members in federations to ensure efficacy [2, 26]. The success of the Turkish Judo Federation (TJF) in the 1990s, winning medals at international competitions, could be attributed to the improved management of their federation. TJF collaborated and worked with other federations, namely Taekwondo, amongst others, to improve their management systems [33]. Turkish Judo Federation is very small compared to the most successful judo countries, namely Japan, France, and Russia. However, the Turkish Judo Federation is far bigger (111 160 registered members), constituting 0.001% of Turkey's population, than JSA (2139 registered members), constituting 0,00004% of the SA population. Informed by the disjuncture in the registration of judokas in the two countries, Turgut et al. [25], propose that the success of judo athletes is determined by the effectiveness of the talent identification process conducted by independent coaches' suitable coaching programs and not the number of registered athletes. In the light of management, athlete talent and coaching programs are the determinants of the federation’s performance. Sam [17] contends that the location of the country in relation to the international competition circuit has an impact on a country’s performance. The furthest country from the international competition circuit is negatively affected. In the interest of athletes, to mitigate this, the furthest countries should arrange international training camps linked to international competitions for their elite athletes. The body of knowledge suggests that performing Judo Federations do not employ the same strategies as outlined in the nine pillars of the SPLISS model; each federation identifies its weakest link or niche and adopts pillar categories that will enhance its performance position [23, 34, 35].

CONCLUSION

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first review to reflect on how judo has navigated and migrated to its current form and what the future holds. The authors acknowledge that the review is not without limitations. The articles reviewed were all in English, this may introduce bias since articles published in other languages may have been missed. Nonetheless, this review can conclusively report the consensus on the past, present, and future in that federations should improve their management systems to support elite athletes and run their administration on a full-time basis to afford athletes optimal attention as well as be able to mobilize resources to run federations efficiently. However, JSA does not seem to be playing in the same league as the rest of the world. The study authors recommend specialization and commercialization to optimize financial resources and athlete management systems.

AUTHOR’S CONTRIBUTION

It is hereby acknowledged that all authors have accepted responsibility for the manuscript's content and consented to its submission. They have meticulously reviewed all results and unanimously approved the final version of the manuscript.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis |

| JBI | Joanna Briggs Institute |

| GBP | Gross Domestic Product |

| SPLISS | Sports Policy Factors Leading to International Sporting Success |

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIAL

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The first author serves as the president of Judo South Africa. The remaining co-authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.