All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Markov Model Predicting Impact of Restriction on the Sale of Flavored Tobacco

Abstract

Introduction

Flavored tobacco restrictions provide an opportunity to reduce tobacco product initiation. However, this policy raises concerns about the decrease in cessation of combustible tobacco due to decreased transition to e-cigarettes.

Methods

We developed a Markov model using transition rates between inhaled tobacco product use states derived from the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) study to assess how a flavored tobacco restriction may impact current users and those at risk of starting tobacco products. This quasi-experimental cohort study assesses the potential impact of flavored restrictions on primary and secondary prevention strategies, providing a cohort and population assessment of flavored tobacco restrictions.

Results

The model predicts that for every million adolescents at risk of starting tobacco, a restrictive flavor policy will have 121,000 fewer people ever using tobacco, with a decrease in every use state. After 10 years of policy for every million people over 21 years old, the model predicts 25,200 fewer tobacco product users and 19,200 fewer combustible tobacco users.

Discussion

We demonstrated that a flavored tobacco restriction would see a short-term increase in combustible use from a substitution effect, before seeing a long-term downward trend in all tobacco product use is largely driven by a reduction in initiation among the youth cohort. Current users would see little to no long-term change in combustible use rates compared to a permissive flavor policy.

Conclusion

These findings support a restrictive flavor policy by showing that current combustible users face minimal to no harm, with significant improvements in tobacco use rates across the population leading to improved community health.

1. INTRODUCTION

Tobacco use remains one of the leading causes of preventable morbidity and mortality worldwide, with cigarette smoking contributing to an estimated 480,000 deaths annually in the United States [1]. Over the past decade, the landscape of tobacco consumption has evolved with the emergence of electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS), commonly referred to as e-cigarettes. Marketed as a less harmful alternative to combustible tobacco, ENDS have gained significant traction, particularly among adolescents and young adults [2].

A key factor driving e-cigarette adoption is the availability of flavored tobacco products, which are particularly appealing to youth [3, 4]. Flavored ENDS play a substantial role in initiation, with research indicating that adolescents and young adults overwhelmingly prefer flavored products over unflavored or tobacco-flavored alternatives [5]. Because nicotine product addiction primarily starts in adolescents [6], primary prevention has targeted flavors in hopes of reducing initiation [7].

Consequently, policymakers have expressed concerns that flavored tobacco products may serve as a gateway to long-term nicotine addiction and potential transition to combustible tobacco use [8], leading to several jurisdictions implementing or proposing restrictions on the sale of flavored tobacco products as a measure to curb youth initiation and reduce overall tobacco consumption [9].

While such restrictions may be effective for primary prevention, they may also have unintended consequences for secondary prevention efforts. Current tobacco users, particularly those who have switched from combustible cigarettes to flavored ENDS, may revert to cigarette smoking if their preferred substitutes are no longer available [10]. This risk also exists for exclusive ENDS users who find unflavored products unpalatable. Even in the presence of flavored ENDS, there is an increased risk of transition to combustible tobacco over non-users [11], which may offset concerns about the secondary prevention benefits of flavored ENDS. The substitution effect between ENDS and combustible tobacco raises concerns about the net impact of flavored tobacco bans, as potential declines in youth initiation must be weighed against the risk of relapse or continued dual use among current users [12, 13].

There is an ongoing debate regarding the role of ENDS as a harm reduction tool, as the long-term health effects of ENDS remain insufficiently characterized. While ENDS are generally considered less harmful than combustible tobacco [14], emerging evidence suggests potential risks related to respiratory and cardiovascular health [15].

This study employs a Markov model to assess the impact of flavored tobacco policy restrictions on tobacco use initiation in adolescents and young adults, and transitions among current users. Markov models use probabilities to transition between states and assume the future state probability is determined only by the present state [16]. By modeling the probability of individuals transitioning between different tobacco use states under both status quo (flavored tobacco permitted) and restrictive policy scenarios (flavored tobacco prohibited), this quasi-experimental study seeks to provide an understanding of the potential benefits and trade-offs associated with restrictions on the sale of flavored tobacco in an idealized complete flavored tobacco restriction scenario that is absent significant black and grey market products. The model utilizes Markov

Transition probabilities were derived by Brouwer et al., who used the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) study [17, 18]. The findings will contribute to ongoing discussions on tobacco control policy, balancing the goal of reducing youth initiation with the need to minimize unintended harm among existing users.

2. METHODS

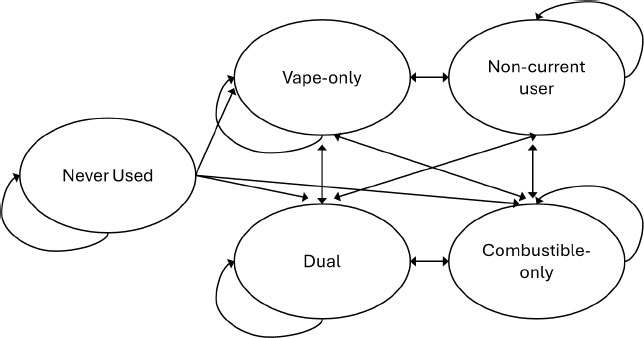

We developed a Markov model to evaluate the impact of flavored tobacco policies on tobacco use patterns within two cohorts: Youth and Adult. Both models incorporate five use states: Never, Non-Current, Exclusive-ENDS, Exclusive-Combustible, and Dual-Use. Transitions between any state occur once each cycle, which is approximately one year, except the Never state, which can only be exited. Figure 1 demonstrates the possible transitions between states. During analysis and comparison of the adult and youth cohorts, each age represented in the model is assumed to have the same number of people (Youth Cohort: 10 years of people, Adult Cohort: 35 years of people). This will be used to assess the prevalence of inhaled tobacco product use among the adult population, defined as over 21 years.

TreeAge Pro 2024 (TreeAge Software, Williamstown, MA) was used to construct and analyze the decision-analytic model. The Markov cycle length was one year, with transitional probabilities extracted from the literature, as will be outlined. Traditional half-cycle.

A correction was used to create a more linear event incidence. Probabilities were entered asbeta distributions with a mean and standard deviation calculated from the mean and a range Table 1.

2.1. Policy Scenarios

Restrictive flavor policy is expected to have two impacts on use patterns. Current users will change their use patterns due to the disruption of available products, which would decrease the likelihood of using flavored products (in this model, ENDS and dual users). This will consequently increase the transition to combustible and non-current states for ENDS users. The second impact will be on the number of young people initiating tobacco products. Because nearly all adults start using before turning 21, it will only have an impact on the youth cohort.

The state transition model illustrates the health states of the youth and adult markovmodels.

| Initial State | End State | Youth Model Transitions | Initial | Prevalence | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Permissive Model | Restrictive Model | Permissive and Restrictive Year 1 | Restrictive | ||||

| Rate | Sensitivity Range | Rate | Sensitivity Range | ||||

| Never | Never | 0.95 | 0.947, 0.953 | 0.958 | 0.955, 0.961 | 0.821 | Y2: 0.8568 |

| Non-Current | 0.021 | 0.019, 0.023 | 0.021 | 0.019, 0.023 | Y3: 0.8926 | ||

| Exclusive Combustible | 0.017 | 0.015, 0.019 | 0.0186 | 0.017, 0.021 | Y4: 0.9284 | ||

| Exclusive ENDS | 0.01 | 0.008, 0.012 | 0.2 | 0.001, 0.003 | Y5+: 0.9646 | ||

| Dual | 0.002 | 0.0005, 0.003 | 0.0004 | 0, 0.0001 | |||

| Non-Current | Non-Current | 0.712 | 0.701, 0.723 | 0.7509 | 0.738, 0.762 | 0 | 0 |

| Exclusive Combustible | 0.224 | 0.202, 0.246 | 0.2363 | 0.213, 0.259 | |||

| Exclusive ENDS | 0.046 | 0.04, 0.058 | 0.0092 | 0.007, 0.011 | |||

| Dual | 0.018 | 0.007, 0.028 | 0.0036 | 0.003, 0.005 | |||

| Exclusive Combustible | Non-Current | 0.132 | 0.123, 0.141 | 0.1426 | 0.134, 0.152 | 0.036 | Y2: 0.0288 |

| Exclusive Combustible | 0.777 | 0.771, 0.783 | 0.8392 | 0.832, 0.845 | Y3: 0.0216 | ||

| Exclusive ENDS | 0.018 | 0.015, 0.02 | 0.0036 | 0.003, 0.004 | Y4: 0.0144 | ||

| Dual | 0.073 | 0.068, 0.078 | 0.0146 | 0.014, 0.016 | Y5+: 0.0072 | ||

| Exclusive ENDS | Non-Current | 0.313 | 0.274, 0.351 | 0.656 | 0.574, 0.735 | 0.125 | Y2: 0.1 |

| Exclusive Combustible | 0.109 | 0.094, 0.124 | 0.2284 | 0.196, 0.26 | Y3: 0.075 | ||

| Exclusive ENDS | 0.456 | 0.423, 0.491 | 0.0912 | 0.085, 0.097 | Y4: 0.05 | ||

| Dual | 0.122 | 0.106, 0.139 | 0.0244 | 0.213, 0.277 | Y5+: 0.025 | ||

| Dual | Non-Current | 0.083 | 0.077, 0.091 | 0.1505 | 0.14, 0.165 | 0.018 | Y2: 0.018 |

| Exclusive Combustible | 0.413 | 0.385, 0.44 | 0.7487 | 0.702, 0.793 | Y3: 0.0144 | ||

| Exclusive ENDS | 0.13 | 0.108, 0.15 | 0.026 | 0.022, 0.03 | Y4: 0.0072 | ||

| Dual | 0.374 | 0.349, 0.399 | 0.0748 | 0.069, 0.079 | Y5+: 0.0036 | ||

| Never | Never | 0.9706 | 0.966, 0.975 | 0.972 | 0.969, 0.976 | 0.644 | |

| Non-Current | 0.0169 | 0.015, 0.019 | 0.0169 | 0.015, 0.019 | |||

| Exclusive Combustible | 0.0106 | 0.007, 0.014 | 0.0107 | 0.01, 0.012 | |||

| Exclusive ENDS | 0.0018 | 0.001, 0.026 | 0.0004 | 0.0001, 0.0014 | |||

| Dual | 0.0001 | 0, 0.0001 | 0 | 0, 0.0001 | |||

| Non-Current | Non-Current | 0.9101 | 0.905, 0.916 | 0.9188 | 0.913, 0.923 | 0.209 | |

| Exclusive Combustible | 0.0746 | 0.07, 0.08 | 0.0782 | 0.071, 0.084 | |||

| Exclusive ENDS | 0.0117 | 0.01, 0.014 | 0.0023 | 0.001, 0.003 | |||

| Dual | 0.0036 | 0.003, 0.005 | 0.0007 | 0.0005, 0.002 | |||

| Exclusive Combustible | Non-Current | 0.0861 | 0.08, 0.092 | 0.0899 | 0.084, 0.096 | 0.102 | |

| Exclusive Combustible | 0.8621 | 0.855, 0.868 | 0.8997 | 0.892, 0.905 | |||

| Exclusive ENDS | 0.01 | 0.008, 0.011 | 0.002 | 0.001, 0.003 | |||

| Dual | 0.0418 | 0.039, 0.045 | 0.0084 | 0.006, 0.01 | |||

| Exclusive ENDS | Non-Current | 0.1843 | 0.159, 0.206 | 0.6122 | 0.536, 0.686 | 0.032 | |

| Exclusive Combustible | 0.0719 | 0.062, 0.082 | 0.2388 | 0.205, 0.273 | |||

| Exclusive ENDS | 0.6032 | 0.573, 0.633 | 0.1209 | 0.115, 0.127 | |||

| Dual | 0.1406 | 0.125, 0.16 | 0.0281 | 0.024, 0.032 | |||

| Dual | Non-Current | 0.0388 | 0.035, 0.043 | 0.0713 | 0.039, 0.046 | 0.013 | |

| Exclusive Combustible | 0.4494 | 0.337, 0.562 | 0.8264 | 0.658, 0.744 | |||

| Exclusive ENDS | 0.0871 | 0.065, 0.109 | 0.0174 | 0.036, 0.052 | |||

| Dual | 0.4247 | 0.399, 0.449 | 0.0849 | 0.079, 0.089 | |||

We analyzed both cohorts under two policy conditions: a Permissive Flavor Policy (control) and a Restrictive Flavor Policy (variable). For this model, we assumed ENDS products are exclusively flavored, and the impact of this policy, and that combustible tobacco is not. The Restrictive Flavor Policy assumes an 80% reduction in ENDS use, affecting transitions into and maintenance of Exclusive-ENDS and Dual-Use states [19, 20]. The decreased transition probability to ENDS and Dual-Use is redistributed to Never, Non-Current, and Exclusive-Combustible states, which were increased proportionately to the Control state’s baseline transition probabilities. We believe this approach minimizes bias in the absence of higher-quality data. The result of this policy would therefore increase Non-Current and Exclusive-Combustible while also decreasing transition out of the Never state.

The second impact is a change in the initiation rate for at-risk individuals Youth Cohort. The model decreases the initial rate over the course of 5 cycles to the target of 80% representing a decrease in initiation.

The target of 80% was selected based on youth surveys indicating 80% would attempt to quit ENDS in the absence of flavors [19, 20]. This rate is considerably higher than what’s been reported following some local or state flavor restrictions; however, prior reports on local and state restrictions are limited by both the short duration of restrictive policy and ease of access for flavored tobacco products within the restricted jurisdiction [21], or the substitution effect dominates the effect in cases of incomplete flavor restrictions [22]. Experience in Massachusetts and New Jersey describes a reduction in sales of non-tobacco flavored ENDS from 83 to 99%, a reduction in tobacco flavored cigarettes by 13 to 22%, and a reduction in menthol cigarettes by 95% in Massachusetts following their sales restrictions [23]. We believe these findings generally support the proposed transition changes in the model.

A challenge with early assessment of flavored tobacco restriction in the literature is the short duration and ease of access to grey market, black market, or legal products sold despite regulations, and those states with incomplete flavor restrictions. Because of this, we do not believe that early data on local or state restrictions accurately reflect changes in use patterns, especially initiation among youth.

2.2. Adult Cohort Model

The Adult cohort consists of individuals aged 21 to 55 at model initiation, ending the model 31 to 65. We assume each age year is equally populated. Initial use state distributions were assigned based on national tobacco use survey data [24-26]. Since age influences transition probabilities, the model incorporates weighted probabilities derived from Brouwer et al., integrating transition probabilities for the 18–24, 25–34, and 35–55 age groups to reflect the cohort’s aging distribution over the study period.

Brouwer provided several transition rates for various demographic groups. We selected age-based groups for two reasons. First, our model is cohort by age, so this naturally added simplicity to the model. Second, age includes all demographics and other risk factors found within the PATH population; therefore, if the PATH study population is representative of the general population, any variation in risk from individual factors should be represented by these values.

2.3. Youth Cohort Model

The Youth cohort differs from the Adult model due to the dynamic nature of tobacco initiation risk between ages 10 and 20 (the cohort's age at model initiation). Initial use rates for the Permissive Flavor Policy are from population surveys [24-26] and remain static through the model. In contrast, the Restrictive Flavor Policy will gradually affect initiation and transition rates. Older adolescents exposed to a permissive policy for a greater proportion of their adolescence are assumed to have a higher risk of initiating tobacco use compared to younger adolescents who experience a restrictive policy for more of their teen years. Furthermore, as tobacco initiation risk is primarily concentrated in mid-to-late adolescence, the Youth cohort cannot be treated as a homogeneous group across the model duration, and data on transition rates for young teens are not known.

To account for these variables, we made two key adjustments to account for these complexities. First, individuals enter the Youth model at age 20 in yearly waves, with initial use states (time = 0) assigned based on population survey data. Once entered, transitions occur annually between use states according to the model’s Markov probabilities, creating >a total of 10 equal sub-cohorts. Each new cohort year is added to the model sequentially, with each sub-cohort running for 10-n years (where n is the number of years since model initiation).

Second, in the Restrictive Policy scenario, initiation rates decline at a linear rate over the first four years of implementation (Years 1–4) until reaching the target reduction level.

From Year 5 onward, initiation rates remain static.

2.4. Transition Probabilities

Markov models assume that transition probabilities depend only on the current state. Transition probabilities were derived from Brouwer et al., with age-stratified estimates applied to each cohort [17]. The Youth model utilized unmodified transition probabilities for the 18–24 age group for the permissive policy state, which were modified for the restrictive policy state as described above in Policy Scenarios. In contrast, the Adult model applied weighted probabilities from the 18–24, 25–34, and 35–55 age groups to reflect the changing age composition of the cohort over time for the permissive policy state, which were modified for the restrictive policy state as described above in Policy Scenarios (Table 1).

3. RESULTS

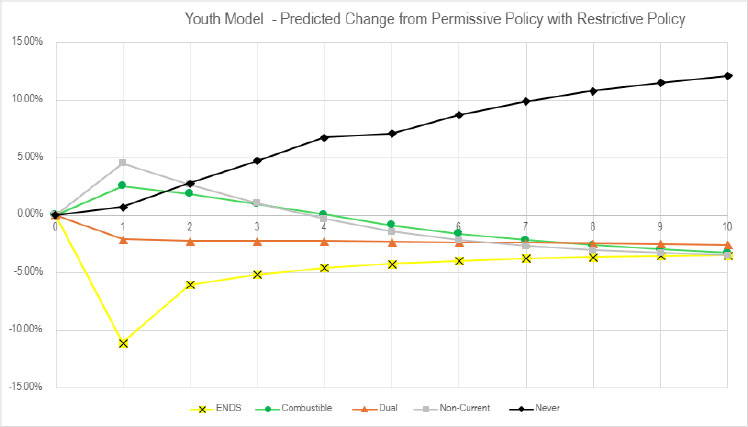

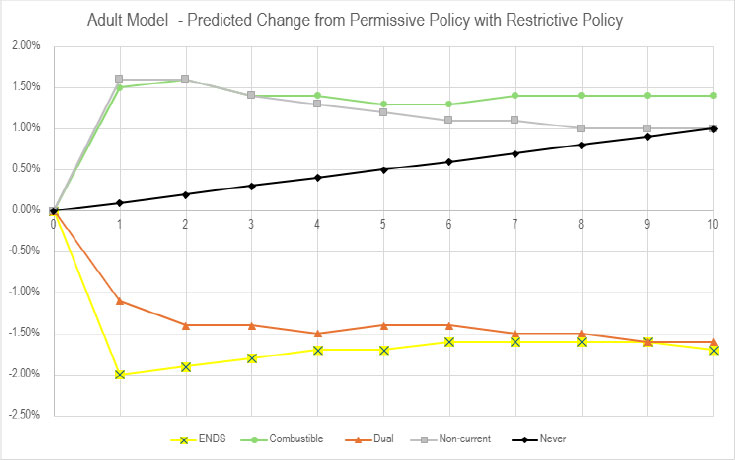

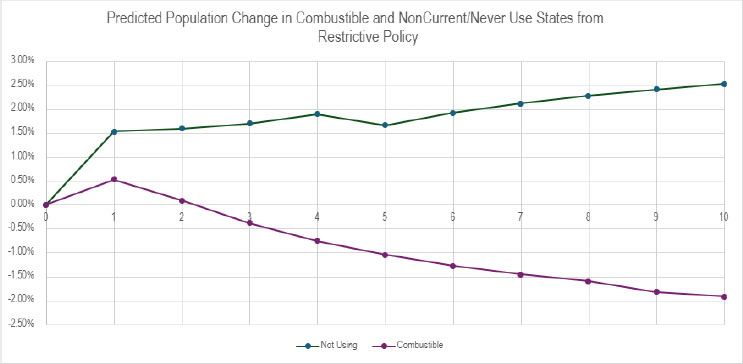

Figures 2 through 5 illustrate the predicted changes in tobacco use states under a restrictive flavor policy, represented as the difference in prevalence in use states between the restrictive and permissive policy scenarios.

Figures 2 and 3 depict the projected impact of a restrictive policy on tobacco use among youth and adult cohorts, respectively.

In the Youth Model, implementing a restrictive policy is predicted to result in an initial increase in combustible tobacco use compared to the permissive scenario, followed by a gradual decline over subsequent years, ultimately leading to a net decrease. We observed a similar trend for the Non-Current use state. The model predicts that the proportion of individuals in the Exclusive-ENDS and Dual-Use states declines sharply following policy enactment and stabilizes thereafter. Conversely, the Never-Use state is projected to increase consistently throughout the modeled period.

Youth Model: Predicted difference by year from permissive policy to a restrictive policy by current use state. The Y axis describes the change in the percentage of the cohort in each use state. X-axis: Time (years), Y Axis: Percentage change between models.

Adult Model: Predicted difference by year from permissive policy to a restrictive policy by current use state. X-axis: Time (years), Y Axis: Percentage change between models.

This predicts that for every million persons in the youth cohort, a restrictive flavor policy would increase the number of Youth in the Never-Use state by 121,000, with a decrease in Exclusive-ENDS by 35,000, Exclusive-Combustible by 32,800, Dual-Use by 25,800, and Non-Current use by 35,300.

In the Adult Model, a restrictive policy predicts a sustained decline in the Exclusive-ENDS and Dual-Use states, accompanied by an increase in Exclusive-Combustible and Non-Current use states over time. The Never-Use state will experience a modest linear increase post-policy enactment. Notably, the increase in Non-Current use is less than the combined decrease in Exclusive-ENDS and Dual-Use, suggesting a shift of users from Exclusive-ENDS and Dual-Use states to the Exclusive-Combustible use state.

For every million adults, this would predict an increase of Never and Non-Current users by 10,000 each, an increase in Exclusive-Combustible users by 14,000, a decrease in Exclusive-ENDS by 17,000, and Dual-User by 16,000.

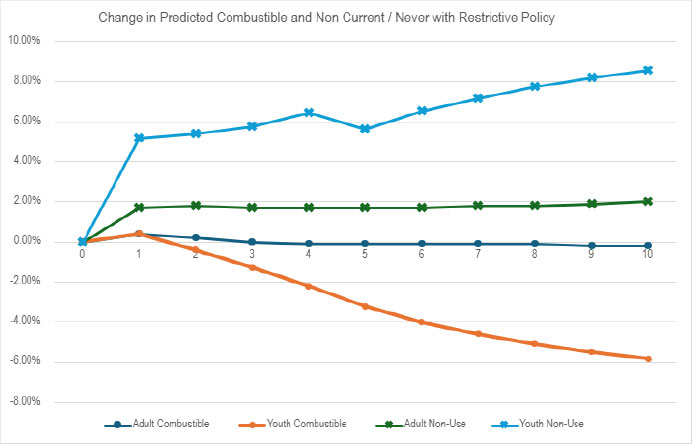

As shown in Fig. (4), combustible tobacco use initially increases after implementing a restrictive flavor policy, followed by a decline over time in both cohorts. Among youth, this decline is projected to be more substantial and continuous. In contrast, the adult cohort is expected to experience minimal change in combustible use, with population-level differences remaining within a narrow range (-0.1% to -0.2%). The projected changes in non-use states (Never and Non-Current) indicate a net increase in non-users across both cohorts. A reduction in ENDS use among adults drives this increase. In contrast, among the youth cohort, reductions in both ENDS and combustible tobacco use contribute to the net increase in non-use states.

Figure 5 accounts for differences in cohort population size, showing the cumulative population-level impact of the policy. The model predicts that a restrictive policy would see a sustained increase in Non-Current and Never users over time. Simultaneously, we project a decline in the proportion of individuals in combustible use states (Exclusive- Combustible and Dual-Use), indicating an overall reduction in smoking prevalence at the population level, demonstrating the net benefit of restrictive policy on population health by reducing use states and increasing non-use states.

The model predicts that a restrictive flavor policy would increase the number of people not using any tobacco product by 25,200 and decrease combustible use by 19,200 for every million people.

Any combustible use state (Exclusive and Dual) and any non-current use state (Never and Non-Current) for Youth and Adult Cohorts, Change in use rates from restrictive flavor policy. X-axis: Time (years), Y Axis: Percentage change between models.

Predicted change in Combustible use (Exclusive-Combustible and Dual-States) and Non-Use State (Never and Non-Current States) for both cohorts adjusted for cohort size. X-axis: Time (years), Y Axis: Percentage change between models.

4. DISCUSSION

Most studies on flavored tobacco policy have focused on initiating tobacco use using local, state, or national population surveys [26] or how flavored ENDS may improve cessation efforts, including a Cochrane review on the topic [27]. Due to study design, these studies have a myopic view of how flavors impact public health due to an appropriate focus on their study population, which creates controversy regarding the net impact of a policy beyond the study population.

To further complicate the question, the relative risk of ENDS when compared to combustible or other tobacco products is not known [28]. However, it is suspected to confer a reduced risk of disease and mortality when compared to combustible tobacco [29]. The probable but uncertain risk reduction for current combustible users should be weighed against multiple complex factors: increased youth ENDS initiation [3, 4], increased risk of youth transition to combustible or oral tobacco products [30], emergence of illicit black and gray markets [31], and the time-value impact on multiple future generations.

Our model addresses the problem of narrow focus, allowing for a dynamic comparison of all stakeholder groups focused on the variable of restrictive flavor policy. The model predicts that the percentage using combustible tobacco will fall by an additional 1.9% over 10 years, and the percentage of children who begin and maintain tobacco product use into adulthood will decrease by 12.1%. Considering all use states in both cohorts, this estimates that the percentage of the population using will decrease by an additional 2.52% in the presence of a restrictive flavor policy.

When focusing on the adult cohort, our model predicts an increase in the Exclusive- Combustible state, which was entirely offset by a decline in Dual-Use for a net decline of 0.2% of any combustible use by the end of the model. Should this reflect the in-situ impact of a flavor restriction, the population-level concerns about harm reduction efforts for current combustible users heavily outweigh the harm caused by the predicted increased number of ENDS and combustible users in the Youth Cohort, even before considering a long-term multigenerational impact.

Our model used a relatively short time frame of 10 years. Restrictive flavor policy has a long-term, multigenerational view with a goal of significantly reducing initiation. In contrast, harm reduction focuses on the short-term goal of improving the health of current users. Even absence of a multigenerational outlook, the model suggests that a population benefit could be seen with restrictive policy in as few as 3 years.

With less than 20 years of widespread ENDS use, we lack outcomes data on disease, disability, and death, making the population break-even point when considering healthcare costs and the burden of disease for ENDS vs. combustible tobacco unclear. Regardless, should this policy be given enough time and initiation rates for ENDS and combustible tobacco decline, a restrictive flavor policy would benefit the population.

Early data is mixed in local and state jurisdictions that have passed and implemented restrictions on flavored tobacco sales. Massachusetts saw a decline in sales overall [32], but sales in neighboring states trended upward. However, unadjusted sales did not differ from sales patterns in non-Massachusetts border states [33]. Evaluation of the short-term impact of flavor restrictions has shown an increase in combustible use in adolescents and adults [9, 13, 34]. Whether this increase represents a change in initiation patterns or a short-term substitution effect primarily impacting already addicted current users is important. A sustained upward trend in initiation of combustible tobacco from restrictive flavor policy would support a permissive stance. However, suppose this is a short-term substitution effect like the one predicted in this model. In that case, comparing this change to the long-term increased risk of transition from ENDS to combustible over the non-user and the yet-to-be-determined health impact of long-term ENDS use.

5. LIMITATIONS

The PATH study provided transition variables for model inputs, as described by Brouwer [17, 18]. However, these transition variables covering waves 1–4 may not accurately represent the broader population.

The control group exhibited a trend toward combustible tobacco use and away from ENDS across multiple age groups, differing from population-level surveys. The underlying cause of this discrepancy is unclear but may be attributed to the limited number of waves or differences between the PATH study sample and the general U.S. population.

Consequently, we do not believe the model fully reflects expected population-level outcomes. Despite this, the observed differences between the control and variable groups offer valuable insights into potential changes in use patterns following a flavored tobacco restriction.

Our model assumes that youth and adult cohorts respond similarly to flavored tobacco restrictions. This assumption is uncertain as tobacco use states become more stable with age, suggesting that older adults may be less likely to transition to a non-current use state in response to policy changes. Youth surveys suggest that roughly 80% would attempt to quit if no flavors were available for ENDS products [19, 20]. However, adult surveys suggest a potentially different reaction, with 17% believing they would stop ENDS and transition to combustible tobacco, 12.9% planning to quit, 28% planning to vape with available flavors, and another 28% attempting to get a banned flavor [35]. Flavor restrictions may not evenly impact youth and well-established adult tobacco product users.

To minimize personal bias and uncertainty, we applied existing transition rates and proportionally increased them without more precise data. However, this approach likely overestimates youth transitions to combustible tobacco use, which tend to be less stable in youth, while also overestimating adult transitions to non-current use, as use

states are generally more fixed in older populations, as suggested by the aforementioned surveys.

Based on surveys by Harrel and Sidhu, we assumed an 80% reduction in use [19, 20]. Early studies on flavor restrictions support this assumption, but long-term market responses remain uncertain. The tobacco industry continuously introduces new products designed to attract adolescent and young adult users [36]. Our model does not account for potential market-disrupting products that could alter user preferences and local attitudes toward tobacco and nicotine products.

The model does not account for the potential impact of flavor restrictions on flavored combustible tobacco use. Menthol cigarettes, flavored cigarillo, hookah (water pipes), and pipe tobacco users may modify their use patterns, with some transitioning away from tobacco use entirely [37]. This omission may lead to an underestimation of the overall impact of flavor restrictions on use patterns. Should there be a significant decrease in the demand for ENDS, scarcity or lack of availability in certain regions could be an additional external force for transitioning from ENDS to a combustible or non-current use state.

Our model focuses exclusively on combustible and ENDS products, excluding potential transitions to oral tobacco products such as chewing tobacco, snus, and oral nicotine pouches, which is currently infrequent [38]. Although oral tobacco products represent a minority of tobacco use [39, 40] they could serve as substitutes for ENDS users who seek alternatives to combustible tobacco but are unable to quit altogether. Incorporating oral tobacco transitions into the model would be warranted if transition rates between inhaled and oral tobacco products become available. Furthermore, many jurisdictions include oral tobacco in restrictive flavor policies [41, 42], which could decrease the substitution effect of oral tobacco products.

Markov models assume that prior states do not influence the transition probability to subsequent states [16]. However, this assumption is probably not entirely true. The likelihood of transition is related to age and duration of use [43, 44]. However, our transition probabilities treat these groups equivalently. The absence of data to construct a more complex model incorporating multiple former-use states limits the accuracy of our predictions.

CONCLUSION

According to this model, implementing comprehensive restrictions on flavored ENDS products could lead to a significant reduction in tobacco use over 10 years. This reduction would be primarily driven by a decrease in youth initiation and a modest decline in combustible tobacco use. While short-term increases in combustible tobacco use may occur among current ENDS users, these effects are outweighed by sustained declines in both ENDS and combustible tobacco initiation in adolescents and young adults, highlighting the potential long-term benefits of these restrictions.

Uncertainty remains regarding how users will ultimately adapt to flavor restrictions over longer time horizons and whether emerging products or illicit markets will mitigate intended policy effects. The absence of long-term outcomes data on ENDS-related morbidity and mortality further complicates the evaluation of relative risk and population-level health impact. Nonetheless, the findings from this modeling exercise reaffirm the potential public health benefit of policies aimed at reducing flavored tobacco availability at the population level, primarily driven by the impact on adolescent initiation. This should instill confidence in the proposed policy, as it demonstrates no to minimal impact on adult use patterns compared to a non-restrictive state.

Future work should incorporate additional data on adult behavioral responses, the potential substitution of oral nicotine products, and the impact of enforcement effectiveness on market dynamics. It is crucial to consider these factors, along with further study of health outcomes associated with sustained ENDS use, in refining policy approaches. This will ensure that policies balance harm reduction for existing users with the prevention of tobacco initiation in future generations.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

Study Concept and design, Data collection, Analysis, Interpretation of results, Draft of Manuscript: Bishara, Model Design, and Processing, Draft of Manuscript: Evers. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| PATH | = Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health |

| ENDS | = Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems |

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

The OHSU IRB determined that the proposed activity is not research involving human subjects. IRB review and approval is not required, STUDY00027880.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

All the data and supporting material are available within the article.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.