All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Students’ Knowledge of HIV/AIDS and Stigmatisation of People Living with HIV/AIDS at a Semi-rural South African University

Abstract

Introduction

Research on HIV/AIDS remains a necessity as millions of people still live with the disease, and it continues to have a high impact on many communities in South Africa.

To investigate knowledge of HIV/AIDS and stigmatisation of People Living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) amongst a sample of tertiary education students.

Methods

In this investigation, a quantitative approach was used with a cross-sectional survey design. The aim of the study was to investigate knowledge of HIV/AIDS and stigmatisation of PLWHA amongst a sample of tertiary education students. Data were collected using a questionnaire consisting of three sections. The first section collected demographic information. Thereafter, two standardised and validated survey tools were used, namely the HIV/AIDS Knowledge Scale (α=0.75) and the HIV/AIDS Stigma Scale (α=0.81).

Results

In this study (N=180), 59.4% were male and 40.6% female. Overall, 61% demonstrated adequate/good knowledge of HIV/AIDS, while 39% had poor/inadequate knowledge. Chi-square tests indicated no significant gender difference in knowledge (x2=0.25, p=0.05), but a significant gender difference in stigma was found (x2=3.95, p=0.01). Effect sizes were small to moderate (Cramér’s V=0.12–0.18).

Discussion

It must be noted that the cross-sectional design precludes causal inference. Findings are associations only and may be influenced by unmeasured confounding variables. Nonetheless, the study findings suggest that there are gaps in students’ knowledge about HIV/AIDS. This may explain that students with adequate to good knowledge pertaining to HIV/AIDS stigmatise PLWHA. This is because their overall knowledge about HIV/AIDS is likely to be incomplete, although generally good.

Conclusion

It is recommended that HIV/AIDS workshops on the campus take place, and more research in different educational contexts, such as schools, is required in South Africa.

1. INTRODUCTION

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) continue to have a significant effect on public health worldwide [1]. On the African continent, around 25 million people live with the disease. Moreover, in 2020, an estimated million persons died from HIV related illnesses, even though it is a manageable disease [2]. Although there have been many efforts to address the threat posed by HIV, the youth remain vulnerable in South Africa [3].

According to [4], the first case of AIDS was reported in the early 1980s. In 2018, it was estimated that 770,000 persons had died from HIV related illnesses, while in 2023, it was over a million [2]. During this period, there were 38 million PLWHA, with over 1.7 million becoming infected annually. Moreover, Africa has the highest number of PLWHA, with over 26 million persons living with the disease. This is supported by [5], who report that the HIV epidemic has been severe in many African countries where infections are reported in a significant portion of the population, particularly young women. In 2020, around 410,000 people [6] between the ages of 10–18 years were infected with HIV. It was also noted that sub-Saharan Africa is among the most affected regions.

The concept of HIV stigmatisation can be defined as the negative attitudes and beliefs directed towards people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) [7]. Specific HIV knowledge that can result in a stigmatizing behaviour includes the inaccurate notions on how the virus is transmitted. The misconceptions, such as the belief that HIV can be transmitted by handshaking, hugging, or sharing utensils, can lead to fear of virus acquisition and subsequent stigmatizing behaviour [7].

According to [8], stigma is a significant barrier to HIV treatment and management. HIV remains a highly stigmatized condition because of what are considered high-risk or taboo behaviours associated with its transmission, such as multiple and concurrent sexual partnerships, homosexual intercourse, drug use, and sex work. HIV-related stigma can be experienced as social or internalized self-stigma.

Furthermore [9], indicated that there was a problem in HIV testing and starting antiretroviral therapy during the Covid-19 pandemic in South Africa, although treatment for those receiving the drugs was mostly continued. This may well have caused the disease to progress in some individuals. In this regard [10], postulate that long-term interventions, learned from responses to the HIV/AIDS pandemic, could be useful when applied to future epidemics. A study amongst dental students in India by [11] revealed that they generally knew more about COVID-19 than HIV/AIDS. Moreover, it was suggested that poor knowledge about HIV/AIDS could be problematic if, for instance, they were not aware of ‘blood’ protocols when treating patients with HIV infection. The Social Identity Theory (SIT) was applied from the outset as the theoretical framework to explain group-based stigma processes.

According to the report of [12], in their research, which was conducted in Nigeria, most nursing students had high levels of knowledge about HIV/AIDS. However, 64% of the sample (N=150) had moderately discriminatory attitudes to PLWHA, with 74% engaging in low discriminatory practices and 26% high discriminatory practices towards PLWHA. The study conducted by [13] indicated that HIV/AIDS- related stigma is one of the biggest problems in society, because it affects people’s attitudes towards PLWHA, which leads to their marginalisation and exclusion. That author suggests that the blaming of individuals for becoming infected with HIV helps society excuse itself from the responsibility of caring for and looking after them.

Ominously, the COVID-19 pandemic has relegated the fight against HIV/AIDS and discrimination against PLWHA to the forefront of public opinion. This is a challenge in South Africa as the fight against HIV/AIDS is a long way from being over [14].

Interestingly, early research highlighted a direct relationship between an individual's knowledge of HIV/AIDS and their attitudes towards PLWHA [15-17].

2. STATEMENT OF THE PROBLEM

The research question guiding this study was: 'Does knowledge of HIV/AIDS influence the likelihood of stigmatisation towards PLWHA among students at a semi-rural university?' Two hypotheses were tested: (1) Students have adequate knowledge of HIV/AIDS; (2) Stigmatisation differs significantly by gender.

HIV/AIDS-related stigma is a complex, life-altering social phenomenon, and it was therefore deemed appropriate for the researchers to look at it post the acute COVID-19 pandemic. This study explored whether students’ beliefs and attitudes towards PLWHA are associated with levels of HIV/AIDS knowledge. This led to stigmatising attitudes amongst the rural university community. There is little information about the knowledge of HIV/AIDS and the stigmatisation of PLWHA. To address the issue, it is imperative to acquire a contextualised understanding of how tertiary students view this stigma. In this study, the researchers sought to find out if knowledge of HIV/AIDS has any influence on the stigmatisation of PLWHA. It was also anticipated that by completing the questionnaires, respondents may gain insight into how they think about HIV/AIDS.

This phenomenon has been found to be a major source of stress and a major obstacle to PLWHA care, prevention, and treatment, all of which have an impact on their quality of life. Even though university students' specific knowledge of HIV/AIDS has been thoroughly studied [18], stigma and discrimination against many PLWHA still persist. There are still knowledge gaps, according to other studies [19, 20].

At a rural university in Limpopo Province [18], looked at students’ knowledge and misconceptions about HIV/AIDS. They found that there were many gaps in knowledge and misunderstandings about HIV transmission and prevention. Institutions of higher learning are high-risk sites for HIV infection and spread of the disease, as students often engage in high-risk sexual behaviours [21]. Furthermore [3], report that although students at a medical university in Gauteng, South Africa were found to have good knowledge about HIV/AIDS, many still had multiple sexual partners and did not always wear condoms, which often occurred when they drank alcohol or used substances.

3. AIM OF THE STUDY

The aim of the study was to investigate knowledge of HIV/AIDS and stigmatisation of PLWHA amongst a sample of tertiary education students.

4. LITERATURE REVIEW AND THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

In previous decades many investigations into the level of knowledge that university students have about HIV/AIDS indicated that they had a high level of knowledge. This included general HIV/AIDS knowledge as well as understanding about how HIV is transmitted and prevented [22, 23]. However, in contemporary society, this is not necessarily the case, and many students have inadequate knowledge about HIV/AIDS [24, 18]. According to [14], one of the reasons for this is that COVID-19 has eclipsed the HIV/AIDS pandemic.

According to [25], a study in Ghana reported that HIV stigmatisation occurs in different social domains. Moreover, in their research HIV positive youth felt fear, loneliness, and experienced being devalued as human beings. They also self-internalised aspects of HIV stigma. It was recommended that different societal levels, such as schools and homes, should be targeted with interventions to prevent HIV stigmatisation. In the United Kingdom (UK) [26] reported that people of Caribbean descent experienced HIV stigma emotionally, financially, economically, physically, and socially. Furthermore, they noted that stigma and discrimination cannot be addressed purely through education and that work within cultures is required in terms of exploring traditional concepts of sexuality. Moreover [27], report a negative linear relationship between stigma and HIV knowledge amongst a sample of college students in the United States of America (USA). They recommended that the college should embark on educational interventions to expand knowledge to prevent discrimination and stigmatisation. In a South African study conducted in Tshwane, Gauteng by [28], it was found that the stigmatisation of PLWHA was likely to destabilize HIV/AIDS treatment and intervention plans. Additionally, results indicated that members of the community who were more likely to stigmatise PLWHA were elderly males.

A mixed-methods South African study undertaken by [20] looked at student knowledge, beliefs, and attitudes towards HIV/AIDS at a medical university. They found that although students had fair to good knowledge about HIV/AIDS, there were some gaps. For instance, the majority believed that homosexuals were more likely to have the disease than heterosexuals, which shows bias and discrimination, as the disease is mainly heterosexual in the country. A third of this sample believed that children who play with an HIV positive child are likely to get the disease. Most of the sample (81%) reported stigmatisation of PLWHA.

In another South African study, conducted at a private higher education institution in Johannesburg [29], it was found that female students had significantly less knowledge about the transmission of HIV through unprotected anal sex than males, but there were no significant differences between the genders regarding general HIV/AIDS knowledge. However, this sample was found to have positive attitudes towards PLWHA.

Negative attitudes towards PLWHA remain a major challenge in communities in the fight against HIV/AIDS [30]. Additionally, families and friends of PLWHA also experience stigmatisation. In South Africa, this process has led to the erosion of communal values among Africans. As a result of discrimination, many HIV positive individuals engage in self-stigmatisation. The study conducted by [31] in Durban, South Africa, found that students noted that perceived HIV stigma affected PLWHA negatively in healthcare environments. Furthermore [32], reports that because of discrimination, many HIV positive individuals engage in self-stigmatisation. Fundamentally, this means that they internalize the prejudices and stereotypes that occur in society and feel shame and guilt because of their positive HIV status.

Social Identity Theory (SIT) was used as a theoretical framework for this research, as it provides a platform with which to understand differences in how individuals stigmatise different groups. In addition [33], Tajfel and Turner propose that social behaviours are determined by an individual’s characteristics as well as by the group to which an individual belongs. This theory provides an understanding of people’s beliefs in that they stereotype by exaggerating within-group similarities and the differences between groups [34]. According to this author, SIT is grounded in how individuals (and groups) categorize persons in their social environment. He also states that this happens when people adopt the values and beliefs of the group they belong to and conform to its notions. Moreover, if individuals want to keep their self-esteem positive, they compare themselves favourably with other groups. The group they do not belong to is seen in a negative light. SIT thus helped the researchers to understand how discrimination and stigmatisation occur.

Stigma plays a key role in producing and reproducing relations of power and control, and it causes some groups to be devalued and others to think that they are superior in some way [16]. Therefore, stigma is linked to issues of in-group and out-group perceptions in relation to PLWHA in this research. Again, in the context of this study, this relates to the stigmatisation of PLWHA by students who have adequate, inadequate, poor, or good knowledge about HIV/AIDS.

5. MATERIALS AND METHODS

In this investigation, a quantitative approach was used.

5.1. Research Design

The study utilized a cross-sectional survey design. This type of design is used when data are collected at one point in time [35].

5.2. Population and Area

The study population was undergraduate and post-graduate male and female African students registered at a semi-rural university in Limpopo Province, South Africa.

5.3. Sampling

A convenience sampling method was used. No a priori power analysis was conducted, and the sample was gender-unbalanced (107 males, 73 females). This limitation was acknowledged in the study. A purposive sample was drawn from undergraduate and post-graduate students at the institution. Posters were put up on noticeboards around the institution and in residences, and students were asked to enrol if they were interested in participating in the study by contacting the email address provided. Two hundred of these students responded to the invitation. The final sample was 180, as 20 questionnaires were discarded as they were not completed correctly. One hundred and seven (107) respondents were males, and (73) females. The participants were self-selected to participate in the study since non-probability sampling methods are less objective than probability techniques; hence, purposeful sampling was applied [36].

The study followed the Sex and Gender Equity in Re search guidelines (SAGER) to ensure appropriate inclusion and reporting of sex-related data.

5.4. Procedure

The students who agreed to participate sent their email addresses to the researchers, who emailed them a questionnaire, which was in English, the language of teaching at the institution. The protocol comprised a demographic section and the HIV knowledge and HIV stigma scales. These took an estimated 15 minutes to complete. The completed questionnaires were returned electronically to the researchers, who then analyzed them. Respondents were advised that if they felt uncomfortable in any way after completing the protocols, they could contact the researchers and be referred to a counsellor, who had agreed to help and was based on the campus. No respondents took up this offer. All ethical requirements, such as informed consent and confidentiality agreements, were adhered to. This study obtained ethical clearance from the Turfloop Research Ethics Committee (TREC/90/2021: IR).

5.5. Data Collection Instruments

The instruments were standardised, which negated any bias or ambiguity in the questions, and have proven reliability in cross-cultural contexts. They were therefore deemed appropriate for use in this research. The first part of the questionnaire asked demographic questions such as age, ethnicity, and sex.

5.5.1. HIV/AIDS Knowledge Scale

The HIV/AIDS knowledge scale developed by [37] was used. It is a 12-item scale that measures knowledge about HIV transmission, prevention, and consequences. An example of questions on the scale is: “If a man pulls out right before orgasm (coming), condoms do not need to be used to protect against the AIDS virus.” According to [38], the Cronbach Alpha, which is a measure of internal consistency, i.e. how items on the scale are related to each other, is acceptable to good (α=0.75) when used in multi-cultural contexts.

5.5.2. HIV/AIDS Stigma Scale

A 24-item HIV/AIDS stigma scale developed by [39] was used in the research. The scale measures four separate domains of stigmatisation, namely: (1) fear of transmission and disease; (2) association with shame, blame, and judgment; (3) personal support of discriminatory actions or policies; and (4) perceived community support of discriminatory actions or policies against PLWHA. The scale was found to be valid and reliable in cross-cultural contexts. The Cronbach Alpha for the overall scale was very good at α=0.81.

5.6. Data Analysis

In addition to descriptive statistics (mean, SD), inferential tests included chi-square, cross-tabulations, and correlation analyses (Pearson’s/Spearman’s). Effect sizes (Cohen’s d, Cramér’s V) and confidence intervals were reported to complement p-values.

The collected data were analysed using descriptive statistics, namely, frequencies, percentages, correlations, cross-tabulations, and graphs. According to [37, 40], descriptive statistics are used to describe and summarise data by condensing them in an organised manner. A chi-square test was used to find any significant differences between males and females, and HIV knowledge and stigmatisation in the sample.

Analysis of convenience sample results can only be applied to the study participant group. It is important that associations and effects found with a convenience sample cannot be generalized to a target population [36].

6. RESULTS

6.1. Demographic Results

Respondents were 59.4% male (107) and 40.6% female (73). In terms of age, 51.7% of the sample were 18–20 years of age, 47.8% were aged 20–29 years, and 1 participant (0.6%) was aged 30–39 years. Single respondents made up 96.7% of the sample, cohabiting respondents made up 2.2% (4), and married respondents made up 1.1% (2). One hundred and fifty-two (152) respondents (84%) were registered in undergraduate programmes, and 15.6% (28) were registered in post-graduate studies (Table 1).

| Characteristic | Category | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 107 (59.4%) |

| Female | 73 (40.6%) | |

| Age | 18–20 years | 93 (51.7%) |

| 20–29 years | 86 (47.8%) | |

| 30–39 years | 1 (0.6%) | |

| Marital Status | Single | 174 (96.7%) |

| Cohabiting | 4 (2.2%) | |

| Married | 2 (1.1%) | |

| Level of Study | Undergraduate | 152 (84%) |

| Postgraduate | 28 (15.6%) |

6.2. Knowledge of HIV and AIDS and Stigmatisation

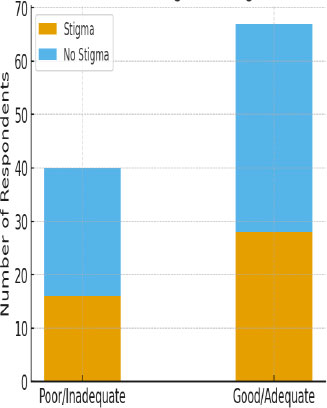

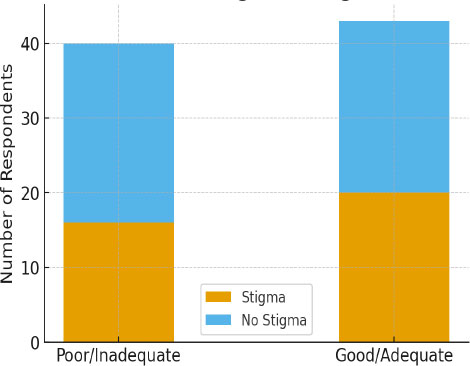

Interestingly, 70 (39%) of the overall sample (n=180) had poor or inadequate knowledge about HIV/AIDS, while 110 respondents (61%) were knowledgeable. A cross-tabulation of knowledge of HIV and AIDS and stigmatisation according to gender revealed the following. A total of 40 (37%) males (n=107) had poor or inadequate knowledge about HIV and AIDS, and of these, 16 (15%) respondents attached stigma to PLWHA while 24 (22%) did not. Sixty-seven males (63%) had good knowledge, but 28 (16%) attached stigma to PLWHA, while 39 (36%) did not. A total of 30 (41%) of the female respondents (n=73) had poor or inadequate knowledge about HIV/AIDS. Of these 24 (33%), none stigmatized PLWHA as compared to 16 (22%) who did. Forty-three of the female respondents had good or adequate knowledge about HIV/AIDS. Of these 20 (27%) stigmatised PLWHA as compared to 23 (32%) who did not see (Figs. 1 and 2).

Correlation between knowledge and stigmatisation of PLWHA (males).

Correlation between knowledge and stigmatisation of PLWHA (females).

Table 2 presents the cross-tabulation of gender × knowledge × stigma scores. These results confirm that although knowledge levels were generally adequate, stigmatisation was more prevalent among female students (57%) than males (31%). Chi-square analysis confirmed significance at p=0.01.

| Gender | Knowledge Level | Stigma (n, %) | No Stigma (n, %) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Poor/Inadequate (n=40, 37%) | 16 (15%) | 24 (22%) | 40 (37%) |

| Male | Good/Adequate (n=67, 63%) | 28 (26%) | 39 (36%) | 67 (63%) |

| Female | Poor/Inadequate (n=30, 41%) | 16 (22%) | 24 (33%) | 30 (41%) |

| Female | Good/Adequate (n=43, 59%) | 20 (27%) | 23 (32%) | 43 (59%) |

6.3. Chi-square Tests (Level of Significance p=0.05)

A chi-square test (level of significance p=0.05) looking at overall knowledge of HIV/AIDS and stigmatisation revealed that there were no significant differences between males and females (df=1; p=0.05). This suggests that stigmatisation towards PLWHA in this sample was not dependent on the knowledge they had about the illness. Conversely, a chi-square test looking at the level of stigmatisation of PLWHA between males and females in the sample found a significant difference between females and males. Females were found to be more stigmatising than males in the sample (df=1; p=0.01). Males had a slightly higher level of knowledge as compared to females, as seen in the descriptive statistics, but this was not at a level of significance (df=1; p=0.05) (Table 3).

| Comparison | df | Chi-square (x2) | p-value | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge of HIV/AIDS × Gender | 1 | 0.25 | 0.05 | Not significant |

| Stigmatisation × Knowledge | 1 | 0.13 | 0.05 | Not significant |

| Stigmatisation × Gender | 1 | 3.95 | 0.01 | Significant (Females more stigmatising) |

7. DISCUSSION

It must be noted that the cross-sectional design precludes causal inference. Findings are associations only and may be influenced by unmeasured confounding variables. There are two levels of discussion, namely knowledge about HIV/AIDS amongst the sample, and male and female stigmatisation of PLWHA. These are discussed in terms of the hypotheses supported by relevant literature and the theoretical framework of the study.

7.1. Knowledge About HIV/AIDS

The first hypothesis states that students have good or adequate knowledge about HIV/AIDS. This is mostly supported, as 61% (n=110) of the overall sample had good or adequate knowledge. However, 39% (70) of the entire sample had poor or inadequate knowledge about HIV/AIDS. This is in line with previous studies, which have found that although many students display adequate or good knowledge about HIV/AIDS [3, 22], there are a growing number that have inadequate or poor knowledge in specific areas [18, 24]. In this research, students who had good or adequate knowledge about HIV/AIDS and those who had poor or inadequate knowledge both stigmatised PLWHA. This is contrary to previous research, which found that educated people were less likely to stigmatise PLWHA [28, 41].

The study findings suggest that there are gaps in students’ knowledge about HIV/AIDS. This may explain, in part, the result that students with adequate to good knowledge pertaining to HIV/AIDS stigmatise PLWHA. This is because their overall knowledge about HIV/AIDS is likely to be incomplete, although generally good.

7.2. Stigmatisation of PLWHA According to Sex

The second hypothesis states that knowledge of HIV/AIDS and stigmatisation differ in terms of sex (males and females). Of the overall sample, 80 respondents (44%) showed stigmatisation towards PLWHA. Fifty seven percent (57%) of the females’ sample showed stigmatising tendencies towards PLWHA as compared to males with 31%. In the chi-square test, looking at significant differences in stigmatising tendencies between males and females, there was a significant difference between the sexes. Females showed more stigmatising tendencies towards PLWHA as compared to males (p=0.01). This finding is consistent with those found in other studies [42, 43]. According to [43], this may be because women suffer many more social consequences than their male counterparts in terms of their sexual behaviour and, as a result, stigmatise any behaviours related to sexuality.

In terms of SIT, the social behaviours of students are not only influenced by their own beliefs but by the group to which they belong [33]). They may belong to a group that stigmatises difference, for instance, PLWHA. Students remain in this type of group because it bolsters their self-esteem as they feel superior to PLWHA. They are very likely to highlight and exaggerate perceived differences in behaviours between their group [34] and PLWHA, which is not based on actual knowledge of HIV/AIDS. For instance, sexual behaviours that are seen as amoral and result in HIV infection may be based on the norms and values in their socio-cultural context, which are difficult to change [28]. Thus, they discriminate against and stigmatise people who are HIV infected or who have AIDS.

8. RECOMMENDATIONS

The research indicates the need for workshops about HIV/AIDS on the campus where the investigation took place. It is likely that existing programmes in the institution need revisions to reflect the current social climate in the country. The need for more and ongoing research in both schools and institutions of higher learning about HIV/AIDS and stigmatisation is still needed.

9. RESEARCH STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS

9.1. Research Strengths

The sample was homogeneous in terms of ethnicity and education. The research process was properly documented and can easily be repeated.

The population categories were sufficiently comprehensive to allow meaningful subgroup comparisons within themselves that were comparatively dissimilar from each other and could not be representative of one another [44].

9.2. Research Limitations

The study was not randomised, meaning that inferential statistics could not be used, and therefore results could not be generalised to other student populations. The sample of males and females was not stratified according to gender; there were more male respondents than females. Additional limitations include potential measurement bias (self-report), social desirability bias in responses, and possible non-response error. These factors may have influenced the observed associations.

9.3. Area for Future Research

Future studies should employ multivariate regression or structural equation modelling (SEM) to explore predictors of stigma and examine mediating/moderating effects. Longitudinal or mixed-method designs would also strengthen causal interpretations.

Also, a larger mixed-methods study on stigmatising attitudes, knowledge, and gender should be undertaken amongst a larger, randomised sample of students. The research should be undertaken in institutions across South Africa to ensure holistic results. A qualitative study looking into the reasons for individual and group stigmatisation of PLWHA is also suggested.

CONCLUSION

In general, the results suggest that the level of knowledge does not influence the stigmatisation of PLWHA by students. However, the differences in stigmatising tendencies towards PLWHA suggest that individual and group stereotyping exists, which is underpinned by concepts within social identity theory. Results from this study indicate that students who endorsed stigmatising views were not necessarily those with poor or inadequate knowledge about HIV/AIDS.

Despite its limitations, this study provides important information about HIV-related knowledge and stigma amongst students. Baseline data are important since the prevalence rate of HIV/AIDS and its related stigma are increasing in South Africa. The need for adequate responses and proper management of the HIV/AIDS pandemic in the country is very important. The HIV/AIDS pandemic has been overshadowed by the COVID-19 pandemic. As such, the present research has shed light on the need to plan and implement new strategies for educating students (and the public generally) about HIV/AIDS, which is rampant amongst the youth in South Africa.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

AJN and KN contributed to the study’s concept, design, data collection, data analysis, and performed the interpretation. DSKH drafted the manuscript and was further involved in revisions. All the authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| HIV | = Human immunodeficiency virus |

| AIDS | = Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome |

| PLWHA | = People living with HIV/AIDS |

| UK | = United Kingdom |

| USA | = United States of America |

| STI | = Social Identity Theory |

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

The study received ethical approval from the Turfloop Research Ethics Committee, South Africa (TREC/90/2021: IR).

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of institutional and/or research committees and with the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki, as revised in 2023.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Informed consent was required from undergraduate and post-graduate male and female African students registered at a semi-rural university in Limpopo Province, South Africa.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIAL

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this research are available within the article.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors want to thank the University in Limpopo for giving us permission to conduct the study. We also want to express our gratitude to the undergraduate and post-graduate male and female African students registered at that semi-rural university.