All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Prevalence and Associated Risk Factors of Gingivitis among Primary School Children (7-11 Years) in Al-Najaf, Iraq: A Cross-sectional Study

Abstract

Introduction

Gingivitis represents the most prevalent form of periodontal disease in children worldwide, characterized by reversible gingival inflammation without loss of connective tissue attachment. Despite its preventable nature, gingivitis affects a substantial proportion of school-age children globally, with prevalence rates that vary significantly across different populations and geographic regions. Limited contemporary data exist regarding gingivitis prevalence among Iraqi children, particularly in the post-conflict era in which healthcare systems and oral health promotion programs have faced significant challenges. The purpose of this study was to determine the prevalence of gingivitis and identify associated risk factors among primary school children aged 7–11 years in Al-Najaf city, Iraq.

Materials and Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted among 531 children (200 boys and 331 girls) from four randomly selected primary schools in Al-Najaf city between December 2021 and January 2022. Clinical examinations included assessment of gingival inflammation using the Löe and Silness Gingival Index and plaque accumulation using the Silness and Löe Plaque Index. Data on oral hygiene practices, sociodemographic factors, and dental care utilization were collected through structured questionnaires. Statistical analysis involved descriptive statistics, chi-square tests, and multivariate logistic regression to identify associated factors.

Results

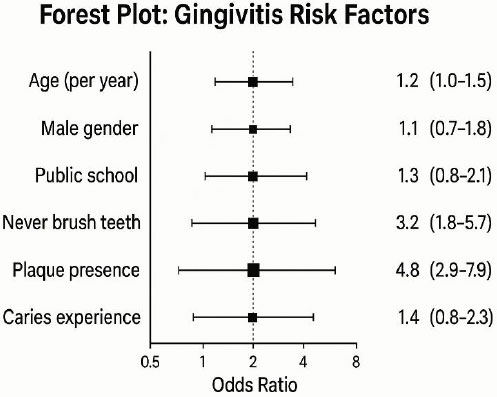

The overall prevalence of gingivitis was 16.6% (88/531), with 83.4% of children showing healthy gingiva. Mild gingivitis was observed in 13.0% of participants, moderate gingivitis in 2.8%, and severe gingivitis in 0.8%. Significant associations were found between gingivitis and toothbrushing frequency (p < 0.001), plaque accumulation (p < 0.001), and dental caries experience (p < 0.05). Children who never brushed their teeth had 3.2 times higher odds of developing gingivitis compared to those who brushed twice daily (OR = 3.2, 95% CI: 1.8-5.7). The presence of dental plaque was the strongest predictor of gingivitis (OR = 4.8, 95% CI: 2.9-7.9).

Discussion

The 16.6% prevalence aligns with global epidemiological data, positioning gingivitis as a significant local health issue. The strong predictive power of plaque presence and lack of toothbrushing confirms that the disease in this cohort is overwhelmingly linked to modifiable hygiene practices. This finding is particularly critical given that over a third of the children reported never brushing, highlighting a substantial gap in basic oral self-care that directly contributes to the observed disease burden. These findings underscore the urgent need for targeted public health interventions, such as school-based oral health programs, to address these modifiable risk factors and improve the oral health of children in this post-conflict region.

Conclusion

The prevalence of gingivitis among schoolchildren in Al-Najaf is consistent with global estimates and shows significant associations with modifiable risk factors. Enhanced oral health education programs and improved access to preventive dental care are essential for reducing the burden of gingival disease in this population.

1. INTRODUCTION

Gingivitis, characterized by reversible inflammation of the gingival tissues without loss of connective tissue attachment, represents the most prevalent form of periodontal disease affecting children and adolescents worldwide [1]. This inflammatory condition manifests clinically as erythema, edema, and bleeding upon probing, typically developing as a consequence of bacterial plaque accumulation along the gingival margin [2]. While gingivitis is generally painless and reversible with appropriate oral hygiene measures, its progression to more severe forms of periodontal disease can result in irreversible tissue destruction and tooth loss if left untreated [3].

Recent global epidemiological data indicate that gingivitis affects approximately 20% of children up to 12 years of age, with significant variations observed across different geographical regions and socioeconomic populations [4]. A comprehensive study by Olczak-Kowalczyk et al. (2024) involving 3,558 children aged 3–7 years reported a gingivitis prevalence of 12.25%, demonstrating the substantial burden of this condition in pediatric populations [1]. Similarly, contemporary research from various countries has documented prevalence rates ranging from 10% to 40%, highlighting the persistent global challenge of maintaining optimal gingival health in children [5, 6]. The etiology of gingivitis in children is multifactorial, with dental plaque serving as the primary etiological factor [7]. The accumulation of bacterial biofilms along the gingival margin triggers an inflammatory response characterized by increased vascular permeability, neutrophil infiltration, and the release of inflammatory mediators [8]. Contributing factors include inadequate oral hygiene practices, dietary habits, socioeconomic status, access to dental care, and individual susceptibility factors [9]. Recent investigations have highlighted the crucial role of oral hygiene behaviors, specifically toothbrushing frequency and technique, in influencing gingival health outcomes in pediatric populations [10].

The school-age period represents a crucial developmental phase for establishing lifelong oral health behaviors and preventing the onset of periodontal diseases [11]. Children aged 7–11 years are particularly vulnerable to gingival inflammation due to several factors, including the mixed dentition period, developing motor skills for effective plaque removal, and varying levels of parental supervision regarding oral hygiene practices [12]. Furthermore, this age group often experiences increased consumption of cariogenic foods and beverages, which can contribute to both dental caries and gingival inflammation [13].

In the Middle Eastern context, limited contemporary data exist regarding the prevalence and associated factors of gingivitis among schoolchildren. Iraq, in particular, has experienced significant challenges in healthcare delivery and oral health promotion due to ongoing socioeconomic difficulties and the long-term effects of conflict [14]. The country’s healthcare system has been severely weakened by decades of war, sanctions, and instability, leading to disruptions in preventive healthcare services and a decline in public health infrastructure [15]. This post-conflict environment creates unique challenges for oral health, as access to dental care, availability of oral hygiene products, and health education programs are often limited. Therefore, prevalence data from a post-conflict region like Al-Najaf is crucial for understanding the specific oral health needs of the population and for developing targeted interventions. Al-Najaf, one of Iraq’s prominent cities with a population exceeding 1.2 million, serves as an essential setting for understanding the oral health status of Iraqi children [14, 15]. Previous studies from the region have suggested varying prevalence rates of gingival diseases, but comprehensive, methodologically rigorous investigations remain scarce [16].

The identification of modifiable risk factors associated with gingivitis in children is essential for developing targeted prevention strategies and public health interventions [17]. Recent systematic reviews have highlighted the effectiveness of school-based oral health education programs in improving gingival health outcomes, emphasizing the importance of early intervention and health promotion activities [18, 19]. Understanding the local epidemiology of gingivitis and its determinants can inform evidence-based policy decisions and resource allocation for pediatric oral health programs.

Given the limited contemporary data on gingivitis prevalence among Iraqi schoolchildren and the need for evidence-based oral health planning, this study aimed to determine the prevalence of gingivitis and identify associated risk factors among primary schoolchildren aged 7–11 years in Al-Najaf City, Iraq. The findings of this investigation will contribute to the growing body of literature on pediatric periodontal epidemiology and provide valuable insights for developing targeted oral health promotion strategies in similar populations.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Study Design and Setting

This cross-sectional epidemiological study was conducted to assess the prevalence of gingivitis and its associated factors among primary school children in Al-Najaf, which is located approximately 160 kilometers southwest of Baghdad and is the fifth-largest city in Iraq, with a population of 1,221,248 according to 2011 census data [20]. The city serves as an essential educational and cultural hub in the region, with a well-established primary education system that includes both public and private institutions.

The study was conducted between December 2021 and January 2022, following approval from the local education authorities and the institutional review board. The timing was selected to avoid major religious holidays and examination periods that might affect school attendance and participation rates.

2.2. Study Population and Sampling

The target population consisted of healthy children aged 7–11 years (±3 months) attending primary schools in Al-Najaf city. A two-stage cluster sampling method was employed to ensure the representative selection of participants. In the first stage, four primary schools were randomly selected from different geographical areas of the city, including two public schools and two private schools, to represent diverse socioeconomic backgrounds. The selected schools were stratified by location (urban center vs. semi-remote areas) to capture potential variations in oral health status and access to dental care.

In the second stage, all classes containing children within the target age range were identified, and systematic random sampling was used to select participants from each grade level. The sampling frame included all children enrolled in grades 1–5 who met the inclusion criteria.

2.3. Sample Size Calculation

A sample size calculation was performed using the formula for cross-sectional studies with a finite population correction. Based on a previous regional study by Rodan et al. (2015) suggesting a gingivitis prevalence of approximately 30% among schoolchildren [21], with a desired precision of 3% and a 95% confidence level, the minimum required sample size was calculated as 512 participants. To account for potential non-response and incomplete examinations, the target sample size was increased to 550 children.

2.4. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.4.1. Inclusion Criteria

• Children aged 7-11 years (±3 months).

• Regular school attendance (defined as attending school for at least 80% of school days in the current academic term, verified through school attendance records).

• Parental/guardian consent and child assent.

• Cooperative behavior during the examination.

2.4.2. Exclusion Criteria

• Children with systemic diseases affecting periodontal health

• Current use of medications known to influence gingival tissues

• Presence of orthodontic appliances

• Developmental dental anomalies

• Recent dental treatment (within 2 weeks)

• Uncooperative behavior prevents adequate examination

2.5. Clinical Examination Procedures

All clinical examinations were performed by a single, calibrated examiner (a dental student) under standardized conditions, using artificial lighting, dental mirrors, periodontal probes, and tweezers. Before data collection, the examiner underwent calibration exercises on 20 children not included in the main study to ensure the consistency and reliability of measurements. The intra-examiner reliability for the gingival and plaque indices was assessed using the Kappa coefficient, which was 0.85, indicating excellent agreement. All clinical examinations were conducted in the school setting, utilizing designated rooms with adequate lighting and privacy. Portable dental examination equipment was used, including dental mirrors, periodontal probes, and portable LED examination lights, to ensure standardized conditions across all examination sites.

2.5.1. Gingival Assessment

Gingival health was evaluated using the Löe and Silness Gingival Index (GI) [22], which assesses the severity of gingival inflammation on a scale of 0-3:

0: Normal gingiva (no inflammation, no color change, no bleeding)

1: Mild inflammation (slight color change, slight edema, no bleeding on probing)

2: Moderate inflammation (redness, edema, glazing, bleeding on probing)

3: Severe inflammation (marked redness and edema, ulceration, spontaneous bleeding). Six index teeth were examined (upper right first molar, upper right lateral incisor, upper left first premolar, lower left first molar, lower left lateral incisor, and lower right first premolar), with four sites per tooth (mesial, distal, buccal, and lingual). The highest score for each tooth was recorded, and the mean GI score was calculated for each participant.

2.5.2. Plaque Assessment

Dental plaque accumulation was assessed using the Silness and Löe Plaque Index (PI) [23] on the same six index teeth:

0: No plaque

1: A Thin film of plaque adhering to the free gingival margin, recognizable only by running a probe across the tooth surface

2: Moderate accumulation of soft deposits within the gingival pocket or on the tooth and gingival margin, visible to the naked eye

3: Abundance of soft matter within the gingival pocket and/or on the tooth and gingival margin

2.6. Data Collection Instruments

A structured questionnaire was administered through face-to-face interviews with the children by the calibrated examiner to collect information on:

• Sociodemographic characteristics (age, gender, school type)

• Oral hygiene practices (tooth brushing frequency, use of fluoride toothpaste, interdental cleaning)

• Dietary habits (frequency of sugar consumption, snacking patterns)

• Dental care utilization (previous dental visits, reasons for visits)

• Parental education level and family income (when available)

The questionnaire was pre-tested on a pilot group of 30 children and modified based on feedback to ensure clarity and comprehensibility.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Data were analysed using SPSS version 23.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive statistics were calculated for all variables, including frequencies, percentages, means, and standard deviations. The prevalence of gingivitis was calculated as the proportion of children with GI scores >0. Categorical variables were compared using the chi-square test or Fisher's exact test, as appropriate. Continuous variables were analysed using independent t-tests or the Mann-Whitney U test, depending on the data distribution. Continuous variables (age, mean plaque index, mean gingival index) were analysed using independent t-tests for normally distributed data or the Mann-Whitney U test for non-normally distributed data. The primary outcome variable (presence/absence of gingivitis) was analysed as a binary categorical variable using chi-square tests for bivariate analysis and logistic regression for multivariate analysis.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to identify independent risk factors associated with gingivitis. Variables with p-values <0.20 in univariate analysis were included in the multivariate model. Odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05 for all analyses.

2.8. Ethical Considerations

The study protocol received approval from the Institutional Review Board of the University of Kufa, College of Dentistry (Ethical Approval Number: UoK-DENT-2021-087, dated November 15, 2021) and the Al-Najaf Education Directorate (Permission Letter: ANJED-2021-234, dated November 20, 2021). Written informed consent was obtained from parents or guardians, and verbal assent was secured from all participating children before their examination. The study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki (2013 revision) and to local ethical guidelines for research involving minors.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Participant Characteristics

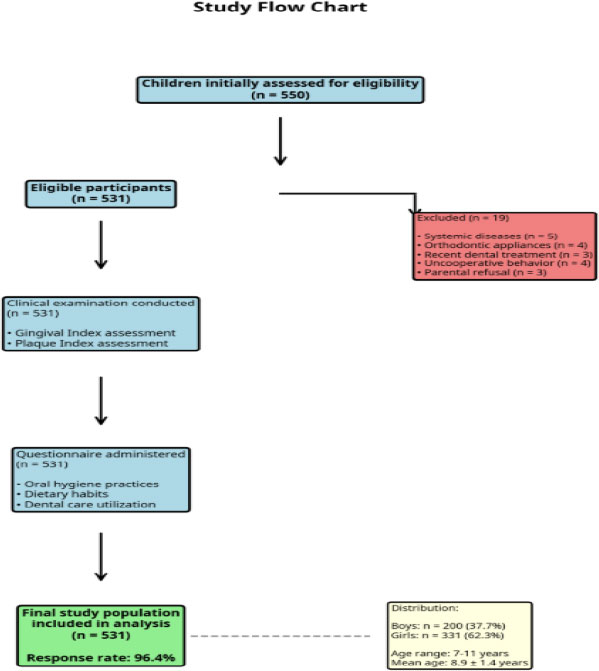

A total of 531 children participated in the study, representing a response rate of 96.4% (Fig. 1). The study population comprised 200 boys (37.7%) and 331 girls (62.3%), with ages ranging from 7 to 11 years (mean age: 8.9 ± 1.4 years). The distribution by age group was as follows: 7-year-olds (n = 89, 16.8%), 8-year-olds (n = 134, 25.2%), 9-year-olds (n = 142, 26.7%), 10-year-olds (n = 118, 22.2%), and 11-year-olds (n = 48, 9.0%). The majority of participants (n = 312, 58.8%) attended public schools, while 219 (41.2%) were enrolled in private institutions Table 1.

3.2. Prevalence of Gingivitis

The overall prevalence of gingivitis (GI score > 0) was 16.6% (88/531), with 443 children (83.4%) exhibiting healthy gingiva (GI score = 0), as shown in Table 1. Among those with gingivitis, the distribution by severity is detailed in Table 2: mild gingivitis (GI score = 1) in 69 children (13.0%), moderate gingivitis (GI score = 2) in 15 children (2.8%), and severe gingivitis (GI score = 3) in 4 children (0.8%). The mean gingival index score for the entire study population was 0.21 ± 0.52.

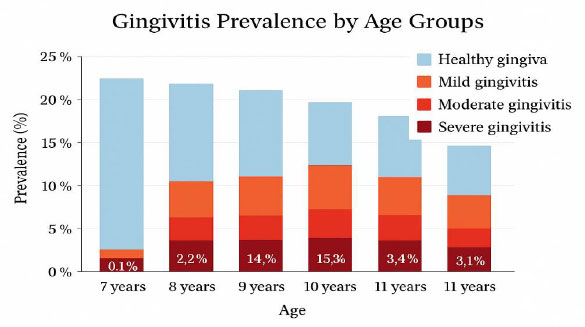

Gender-specific analysis showed that boys had a slightly higher prevalence of gingivitis compared to girls (18.5% vs. 15.4%), although this difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.34), as shown in Table 1. Age-stratified analysis revealed an increasing trend in gingivitis prevalence with age, clearly illustrated in Fig. (2): 7-year-olds (12.4%), 8-year-olds (14.9%), 9-year-olds (17.6%), 10-year-olds (19.5%), and 11-year-olds (22.9%) (p for trend = 0.03).

3.3. Plaque Accumulation Patterns

Assessment of dental plaque revealed that 447 children (84.2%) had no visible plaque (PI score = 0), while 84 children (15.8%) showed varying degrees of plaque accumulation, as detailed in Table 2. Among those with plaque, 53 children (10.0%) had mild plaque accumulation (PI score = 1), 24 children (4.5%) had moderate accumulation (PI score = 2), and 7 children (1.3%) had severe plaque accumulation (PI score = 3). The mean plaque index score was 0.19 ± 0.51 for the entire study population.

| Characteristic | n (%) |

Gingivitis Present n (%) |

Gingivitis Absent n (%) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 0.03* | |||

| 7 | 89 (16.8) | 11 (12.4) | 78 (87.6) | |

| 8 | 134 (25.2) | 20 (14.9) | 114 (85.1) | |

| 9 | 142 (26.7) | 25 (17.6) | 117 (82.4) | |

| 10 | 118 (22.2) | 23 (19.5) | 95 (80.5) | |

| 11 | 48 (9.0) | 11 (22.9) | 37 (77.1) | |

| Gender | 0.34 | |||

| Male | 200 (37.7) | 37 (18.5) | 163 (81.5) | |

| Female | 331 (62.3) | 51 (15.4) | 280 (84.6) | |

| School Type | 0.04* | |||

| Public | 312 (58.8) | 60 (19.2) | 252 (80.8) | |

| Private | 219 (41.2) | 28 (12.8) | 191 (87.2) | |

| Overall Prevalence | 531 (100.0) | 88 (16.6) | 443 (83.4) |

Study flow chart showing participant recruitment and selection process. A total of 550 children were initially assessed for eligibility, of whom 19 were excluded for various reasons, resulting in a final study population of 531.

Prevalence of gingivitis by age groups and severity. The chart shows an increasing trend in gingivitis prevalence with age, from 12.4% in 7-year-olds to 22.9% in 11-year-olds. Most cases were classified as mild gingivitis, with moderate and severe cases being relatively uncommon.

| Index Score | Gingival Index n (%) | Plaque Index n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Score 0 (None/Normal) | 443 (83.4) | 447 (84.2) |

| Score 1 (Mild) | 69 (13.0) | 53 (10.0) |

| Score 2 (Moderate) | 15 (2.8) | 24 (4.5) |

| Score 3 (Severe) | 4 (0.8) | 7 (1.3) |

| Mean ± SD | 0.21 ± 0.52 | 0.19 ± 0.51 |

A strong positive correlation was observed between plaque accumulation and gingival inflammation (Spearman's rho = 0.68, p < 0.001). Among children with no plaque, only 6.7% (30/447) had gingivitis, compared to 69.0% (58/84) of those with any degree of plaque accumulation (p < 0.001), as shown in Table 3.

3.4. Oral Hygiene Practices

Analysis of toothbrushing habits revealed considerable variation in oral hygiene practices, as presented in Table 3. A total of 195 children (36.7%) reported never brushing their teeth, 215 children (40.5%) brushed their teeth once daily, 81 children (15.3%) brushed them twice daily, and 40 children (7.5%) brushed them more than twice daily. Among those who brushed their teeth, 267 children (79.5%) used fluoride toothpaste, while 69 children (20.5%) used non-fluoride toothpaste or were uncertain about fluoride content.

The relationship between toothbrushing frequency and gingivitis was statistically significant (p < 0.001), as shown in Table 3. Children who never brushed their teeth had the highest prevalence of gingivitis (31.3%), followed by those who brushed once daily (12.1%), twice daily (6.2%), and more than twice daily (5.0%). This indicates a clear dose-response relationship between brushing frequency and gum health.

3.5. Associated Factors Analysis

Univariate analysis identified several factors significantly associated with gingivitis prevalence, as summarized in Table 4. Age showed a positive association, with older children having higher odds of developing gingivitis (OR = 1.3 per year increase, 95% CI: 1.1–1.6, p = 0.02). School type was also associated with gingivitis, with children attending public schools having a higher prevalence compared to those attending private schools (19.2% vs. 12.8%, p = 0.04), as shown in Table 1.

Dental caries experience, measured by the dmft/DMFT index, was significantly associated with the presence of gingivitis Table 4. Children with caries experience (dmft/DMFT > 0) had 2.1 times higher odds of having gingivitis compared to caries-free children (95% CI: 1.3–3.4, p = 0.003). The mean dmft/DMFT score was significantly higher in children with gingivitis compared to those with healthy gingiva (2.8 ± 2.1 vs. 1.4 ± 1.8, p < 0.001).

| Variable | n (%) |

Gingivitis Present n (%) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tooth Brushing Frequency | <0.001* | ||

| Never | 195 (36.7) | 61 (31.3) | |

| Once daily | 215 (40.5) | 26 (12.1) | |

| Twice daily | 81 (15.3) | 5 (6.2) | |

| More than twice daily | 40 (7.5) | 2 (5.0) | |

| Fluoride Toothpaste Use (among brushers, n=336) | 0.12 | ||

| Yes | 267 (79.5) | 21 (7.9) | |

| No/Uncertain | 69 (20.5) | 8 (11.6) | |

| Previous Dental Visit | <0.001* | ||

| Never | 298 (56.1) | 63 (21.1) | |

| At least once | 233 (43.9) | 25 (10.7) | |

| Plaque Presence | <0.001* | ||

| No plaque (PI=0) | 447 (84.2) | 30 (6.7) | |

| Any plaque (PI>0) | 84 (15.8) | 58 (69.0) |

Forest plot showing adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for factors associated with gingivitis. Plaque presence was the strongest predictor (OR=4.8), followed by never brushing teeth (OR=3.2). The vertical dashed line represents OR=1.0 (no association).

3.6. Multivariate Analysis

Multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to identify independent predictors of gingivitis after adjusting for potential confounding variables, with results presented in Table 4 and visualized in Fig. (3). The final model included age, gender, school type, toothbrushing frequency, plaque accumulation, and caries experience. The results showed that plaque accumulation was the strongest independent predictor of gingivitis (OR = 4.8, 95% CI: 2.9–7.9, p < 0.001), followed by toothbrushing frequency. Children who never brushed their teeth had 3.2 times higher odds of developing gingivitis compared to those who brushed twice daily (95% CI: 1.8–5.7, p < 0.001). Age remained a significant predictor in the multivariate model (OR = 1.2 per year, 95% CI: 1.0–1.5, p = 0.04), as illustrated in the forest plot (Fig. 3).

| Variable | Crude OR (95% CI) | p-value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (per year increase) | 1.3 (1.1-1.6) | 0.02* | 1.2 (1.0-1.5) | 0.04* |

| Gender (Male vs Female) | 1.2 (0.8-1.9) | 0.34 | 1.1 (0.7-1.8) | 0.62 |

| School Type (Public vs Private) | 1.6 (1.0-2.6) | 0.04* | 1.3 (0.8-2.1) | 0.28 |

| Tooth Brushing Frequency | ||||

| Twice daily | Reference | Reference | ||

| Once daily | 2.1 (0.8-5.4) | 0.13 | 1.8 (0.7-4.6) | 0.22 |

| Never | 6.8 (2.7-17.1) | <0.001* | 3.2 (1.8-5.7) | <0.001* |

| Plaque Presence (Any vs None) | 32.4 (18.2-57.6) | <0.001* | 4.8 (2.9-7.9) | <0.001* |

| Caries Experience (dmft/DMFT >0) | 2.1 (1.3-3.4) | 0.003* | 1.4 (0.8-2.3) | 0.19 |

3.7. Dental Care Utilization

Assessment of dental care utilization patterns revealed that 298 children (56.1%) had never visited a dentist, while 233 children (43.9%) had at least one previous dental visit, as shown in Table 3. Among those who had visited a dentist, the primary reasons were dental pain (n = 156, 67.0%), routine check-up (n = 45, 19.3%), and dental trauma (n = 32, 13.7%). Children who had never visited a dentist showed a significantly higher prevalence of gingivitis compared to those with previous dental visits (21.1% vs. 10.7%, p < 0.001), as presented in Table 3.

The time since the last dental visit varied considerably among those with previous dental experience. Approximately 89 children (38.2%) had visited a dentist within the past year, 78 children (33.5%) had visited 1–2 years ago, and 66 children (28.3%) had their last visit more than 2 years ago. A trend toward higher gingivitis prevalence was observed with increasing time since the last dental visit, although this relationship did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.08).

4. DISCUSSION

This cross-sectional study offers important current evidence on the prevalence and determinants of gingivitis among primary school children in Al-Najaf, Iraq. The overall prevalence of gingivitis at 16.6% aligns with global estimates and shows that gingival inflammation continues to be a significant oral health issue in this population. This finding is particularly noteworthy when compared to the comprehensive study by Olczak-Kowalczyk et al. (2024), which reported a 12.25% prevalence among younger children (3–7 years) in Poland, suggesting that gingivitis prevalence may increase with age during the primary school years [1]. The strong links found between gingivitis and modifiable risk factors, especially dental plaque buildup and toothbrushing frequency, underscore the preventable nature of this condition and the potential for targeted interventions to improve oral health outcomes.

The World Health Organization's recent estimates, indicating approximately 20% prevalence in children up to 12 years of age, further support the validity of our findings within the global context [4].

The age-related increase in gingivitis prevalence observed in this study, from 12.4% in 7-year-olds to 22.9% in 11-year-olds, reflects important developmental and behavioral changes occurring during the primary school period. This trend is consistent with previous epidemiological investigations and can be attributed to several factors, including the transition from primary to mixed dentition, increased independence in oral hygiene practices, and potential changes in dietary habits and parental supervision [24]. The mixed dentition period, characterized by the presence of both primary and permanent teeth with varying eruption stages, creates anatomical challenges for effective plaque removal and may contribute to increased susceptibility to gingival inflammation [25]. Furthermore, as children mature, they often assume greater responsibility for their oral hygiene routines, which may result in less consistent or effective plaque control compared to parental supervision in younger children. The increase in gingivitis prevalence with age during the primary school years emphasizes the importance of early intervention and establishing effective oral hygiene habits during this critical developmental period.

The strong association between dental plaque accumulation and gingivitis observed in this study reinforces the fundamental role of bacterial biofilms in the pathogenesis of gingival inflammation. The finding that 69.0% of children with any degree of plaque accumulation had gingivitis, compared to only 6.7% of those without visible plaque, demonstrates the critical importance of effective plaque control in maintaining gingival health. This relationship is well-established in the periodontal literature and has been consistently reported across different populations and age groups [26]. The correlation coefficient of 0.68 between plaque and gingival indices in our study is comparable to values reported in recent pediatric studies, indicating that plaque remains the primary modifiable risk factor for gingivitis in children [27].

The findings reveal significant deficiencies in oral hygiene practices, with over one-third of children never brushing their teeth and limited access to preventive dental care. The finding that 36.7% of children never brush their teeth is concerning and substantially higher than rates reported in developed countries, where regular toothbrushing is more universally practiced [28]. This disparity may reflect socioeconomic factors, limited access to oral hygiene products, inadequate oral health education, or cultural differences in oral hygiene practices. These observations highlight the urgent need for comprehensive oral health promotion strategies that address both individual behaviors and systemic barriers to optimal oral health. The clear dose-response relationship between toothbrushing frequency and gingivitis prevalence, with a progressive reduction in inflammation from 31.3% in non-brushers to 5.0% in frequent brushers, underscores the preventive potential of improved oral hygiene behaviors.

Recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses have consistently demonstrated the effectiveness of regular toothbrushing with fluoride toothpaste in preventing and reducing gingival inflammation in children [29, 30]. The observation that 79.5% of children who brushed their teeth used fluoride toothpaste is encouraging, as fluoride provides additional benefits beyond mechanical plaque removal, including antimicrobial effects and enamel remineralization [31]. However, the substantial proportion of children with inadequate brushing frequency highlights the need for targeted interventions to improve oral hygiene practices in this population. From a clinical perspective, the results support the implementation of evidence-based prevention strategies, including regular toothbrushing with fluoride toothpaste, professional oral health education, and improved access to preventive dental services. The school setting represents an ideal platform for delivering population-based interventions that can reach large numbers of children and potentially reduce oral health inequalities.

The association between dental caries experience and gingivitis observed in this study reflects the shared risk factor approach to oral diseases, where common determinants such as poor oral hygiene, dietary factors, and limited access to preventive care contribute to multiple oral health conditions simultaneously [32]. Children with caries experience had 2.1 times higher odds of having gingivitis, which is consistent with findings from recent epidemiological studies demonstrating clustering of oral diseases within individuals [33]. This relationship has important implications for preventive strategies, as interventions targeting common risk factors can potentially address multiple oral health problems concurrently, improving cost-effectiveness and population health outcomes.

The socioeconomic gradient observed in this study, with higher gingivitis prevalence among children attending public schools compared to private institutions, reflects broader health inequalities that affect oral health outcomes. This disparity likely encompasses multiple factors, including family income, parental education, access to dental care, and availability of oral hygiene resources [34]. Recent research has emphasized the importance of addressing social determinants of health in oral disease prevention, recognizing that individual behavioral interventions alone may be insufficient to eliminate health inequalities [35]. The finding that 56.1% of children had never visited a dentist further illustrates the challenges in accessing preventive dental care in this population and highlights the need for improved healthcare delivery systems.

The multivariate analysis results provide valuable insights into the independent contributions of various risk factors to gingivitis development. The identification of plaque accumulation as the strongest predictor (OR = 4.8) confirms the primacy of bacterial factors in gingivitis etiology and supports the continued emphasis on plaque control in prevention strategies. The persistent significance of toothbrushing frequency in the multivariate model (OR = 3.2 for never brushing vs. twice daily) demonstrates that behavioral factors remain important even after accounting for plaque levels, suggesting that brushing frequency may serve as a proxy for overall oral health awareness and self-care behaviors.

Contemporary research has increasingly focused on developing and evaluating school-based oral health interventions, recognizing schools as ideal settings for reaching large numbers of children and implementing population-level prevention strategies [36]. Recent studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of supervised toothbrushing programs, oral health education initiatives, and fluoride varnish applications in school settings [37, 38]. The findings of this study support the potential value of such interventions in the Al-Najaf context, where significant proportions of children exhibit poor oral hygiene practices and limited access to dental care [39, 40].

The study's strengths include its representative sampling methodology, standardized clinical examination procedures, and comprehensive assessment of potential risk factors [41, 42]. The use of established indices for gingival and plaque assessment ensures comparability with international studies, facilitating meta-analyses and systematic reviews. The relatively large sample size provides adequate statistical power to detect meaningful associations and supports the generalizability of the findings to the broader population of schoolchildren in Al-Najaf.

Several limitations should be acknowledged when interpreting the findings of this study. The cross-sectional design precludes the establishment of causal relationships between risk factors and gingivitis, limiting our ability to determine temporal sequences in disease development. The reliance on self-reported data for oral hygiene practices and dietary habits may have introduced recall bias and social desirability bias, potentially affecting the accuracy of behavioral assessments. Additionally, the study was conducted in a single city (Al-Najaf), which may limit the generalizability of findings to other regions of Iraq or countries with different socioeconomic, cultural, and healthcare contexts.

The public health implications of these findings extend beyond individual clinical care to encompass policy development and healthcare system strengthening. The high proportion of children with no previous dental visits indicates the need for expanded access to preventive services and the integration of oral health into broader healthcare delivery systems. Investment in oral health promotion programs, particularly those targeting school-age children, could yield significant long-term benefits for population health and healthcare cost reduction.

Future research directions should include longitudinal studies to better understand the natural history of gingivitis in children and identify critical periods for intervention. Investigating the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of various prevention strategies in the local context would provide valuable evidence for policy decision-making. Additionally, research examining the role of social determinants of health in oral disease patterns could inform more comprehensive approaches to addressing health inequalities.

CONCLUSION

This cross-sectional study offers important current evidence on the prevalence and determinants of gingivitis among primary school children in Al-Najaf, Iraq. The overall prevalence of gingivitis at 16.6% aligns with global estimates and shows that gingival inflammation continues to be a significant oral health issue in this population. The strong links found between gingivitis and modifiable risk factors, especially dental plaque buildup and toothbrushing frequency, underscore the preventable nature of this condition and the potential for targeted interventions to improve oral health outcomes.

The findings reveal significant deficiencies in oral hygiene practices, with over one-third of children never brushing their teeth and limited access to preventive dental care. These observations highlight the urgent need for comprehensive oral health promotion strategies that address both individual behaviors and systemic barriers to optimal oral health. The increase in gingivitis prevalence with age during the primary school years emphasizes the importance of early intervention and establishing effective oral hygiene habits during this critical developmental period.

From a clinical perspective, the results support the implementation of evidence-based prevention strategies, including regular toothbrushing with fluoride toothpaste, professional oral health education, and improved access to preventive dental services. The school setting represents an ideal platform for delivering population-based interventions that can reach large numbers of children and potentially reduce oral health inequalities.

The public health implications of these findings extend beyond individual clinical care to encompass policy development and healthcare system strengthening. The high proportion of children with no previous dental visits indicates the need for expanded access to preventive services and the integration of oral health into broader healthcare delivery systems. Investment in oral health promotion programs, particularly those targeting school-age children, could yield significant long-term benefits for population health and healthcare cost reduction.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| ANJED | = Al-Najaf Education Directorate |

| CDC | = Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

| CI | = Confidence Interval |

| CPITN | = Community Periodontal Index of Treatment Needs |

| DMFT | = Decayed Missing, Filled Teeth (permanent dentition) |

| GI | = Gingival Index |

| IBD | = Inflammatory Bowel Disease |

| OR | = Odds Ratio |

| PI | = Plaque Index |

| SD | = Standard Deviation |

| SPSS | = Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

| UoK | = University of Kufa |

| WHO | = World Health Organization |

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

The authors contributed to this manuscript as follows: H.J.A.: Conceptualization was performed; B.M.A.: Methodology; Z.S.M.: Validation; S.M.I.: Investigation; H.J.A.: Resources provided; B.M.A.: Data curation; Z.S.M.: Original draft preparation.; S.M.I.: Review and editing; and S.M.I.: Supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

The study protocol received approval from the Institutional Review Board of the University of Kufa, College of Dentistry (Ethical Approval Number: UoK-DENT-2021-087, dated November 15, 2021) and the Al-Najaf Education Directorate (Permission Letter: ANJED-2021-234, dated November 20, 2021)

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or research committee, the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki, as revised in 2013, and local ethical guidelines for research involving minors.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

The data and materials generated and analyzed during this study are accessible upon reasonable request.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank the school administrators, teachers, parents, and children who participated in this study. We also acknowledge the support of the Al-Najaf Education Directorate for facilitating access to the schools.