All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Psychosocial Risk Factors and Absenteeism: A Multivariate Case Study in a Metalworking Company in Ecuador

Abstract

Introduction

Psychosocial risks are key determinants of occupational absenteeism, yet their role in Ecuador’s manufacturing sector remains underexplored. This study aimed to examine the relationship between psychosocial risk factors and absenteeism in a metalworking company through multivariate analysis.

Materials and Methods

A cross-sectional, quantitative, and correlational design was applied to all 60 employees of INMEDECOR S.A. (Quito, Ecuador). Psychosocial risks were assessed with the validated National Psychosocial Risk Questionnaire, covering eight dimensions. Absenteeism data were obtained from company records between July 2023 and June 2024, excluding scheduled leaves. Spearman correlations and multiple linear regression were conducted to determine associations between psychosocial dimensions and absenteeism rates.

Results

The company reported an absenteeism rate of 3.83%. The regression model explained 77.1% of the variance in absenteeism. Among the eight psychosocial dimensions, three showed statistically significant associations: workload and work pace (B = -0.331, p = 0.000), recovery (B = -0.168, p = 0.000), and double presence (work–family) (B = -0.418, p = 0.000).

Discussion

Findings confirmed that psychosocial risks significantly influence absenteeism. Recovery and double presence represented the highest perceived risks, reflecting difficulties in work–life balance and insufficient recovery. Workload and work pace also emerged as central predictors, consistent with international evidence.

Conclusion

Absenteeism in the analyzed metalworking company was strongly associated with psychosocial risk factors. Targeted interventions in workload management, recovery promotion, and work–life balance policies are crucial to reduce absenteeism and safeguard employee well-being in industrial contexts.

1. INTRODUCTION

The impact of psychosocial risks on work absenteeism has become a growing concern in occupational health research, as these demands may trigger not only harmful physical conditions but also significant mental health disorders [1]. According to the International Labor Organization, absenteeism is defined as failure to report to work as scheduled [2]. This can lead to decreased productivity, increased workload for remaining employees, and increased operating costs [3]

Although physical health problems are often cited as primary causes, there is extensive evidence that psychosocial factors in the work environment play a key role in absenteeism [4]. These factors include excessive workload, low job control, low organizational support, inadequate leadership, and work-life conflict. When these unfavorable conditions or stressors persist, they can lead to physical and emotional exhaustion, resulting in poor health, which in turn increases the likelihood of absenteeism.

In developing countries, and particularly in Latin America, the intrinsic relationship between psychosocial factors in the workplace and absenteeism remains an under-explored area, despite its undeniable and growing relevance to employee productivity and well-being [5, 6]. In this region, many organizations face persistent structural and cultural challenges that can increase exposure to psychosocial stressors, such as limited access to mental health services, rigid working conditions, and high levels of job insecurity [7, 8]. Such conditions not only impact individual health but also generate significant costs for businesses and national economies.

In this context, Ecuador's manufacturing sector plays a vital role in the national economy, contributing significantly to employment, industrial production, and exports. However, the working conditions inherent to this sector are often characterized by high physical demands, repetitive tasks, long shifts, rigid schedules, and constant pressure to meet production targets [9, 10]. All these factors increase workers' exposure to psychosocial risks, as they can lead to limited control over their tasks, insufficient recovery time, and considerable difficulties in balancing work and personal responsibilities [7].

Despite these persistent challenges and their potential impact on the workforce, empirical research specifically addressing the psychosocial determinants of absenteeism in Ecuadorian manufacturing environments is notably scarce [11, 12]. Most studies available in the region have traditionally focused on physical risk factors or general occupational health outcomes, leaving a critical gap in the understanding of the psychological and organizational drivers of absenteeism [7, 8, 13, 14]. This study attempted to address this gap by applying a multivariate analysis to examine which psychosocial risk factors are significantly associated with absenteeism in a metalworking company in Ecuador.

Furthermore, at the industrial level, workforce stability is critical for manufacturing companies to meet production quotas and maintain operational efficiency. Consequently, absenteeism in this context can have disproportionately negative effects, such as production delays, quality issues, and increased workload for existing staff. Despite these economic and well-being implications, psychosocial risks in the manufacturing industry have received comparatively less attention in occupational health research than in sectors, such as healthcare or education. Therefore, research on these risks in the manufacturing sector is essential to develop effective interventions to reduce absenteeism, improve working conditions, and safeguard the mental and physical well-being of workers in one of the most economically strategic sectors [15].

Leading international organizations, such as the International Labor Organization (ILO), the European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (EU-OSHA), and the Institute for Work and Health (IWH), have repeatedly emphasized the critical importance of addressing psychosocial risks in the workplace. Their goal is to prevent adverse outcomes, such as burnout, decreased performance, and absenteeism, by consistently promoting the systematic assessment of psychosocial risks and organizational-level interventions as key strategies for occupational health. Research conducted in numerous high-income countries has provided substantial evidence of the direct link between psychosocial factors and absenteeism [16, 17].

However, at the Latin American level, there is still a considerable lack of solid empirical information [18]. This limitation restricts the ability of policymakers and employers to design and implement solutions that are culturally and contextually appropriate to the realities of the region. This gap underscores the urgency of conducting empirical research in Latin American contexts to fully understand how psychosocial risks manifest themselves in various work environments and influence employee behavior [19].

To respond specifically to the need for culturally relevant assessment tools in the Latin American context, given the importance of methodological adaptation and regional particularities [20, 21], at the local level, the Ecuadorian Ministry of Labor has developed a National Psychosocial Risk Assessment Questionnaire [22]. This instrument is specifically designed to reflect the organizational and sociocultural particularities of the country. It is extremely important to note that it has undergone rigorous large-scale psychometric validation, demonstrating high internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha = 0.967) and satisfactory construct validity in its eight dimensions. Its use is mandatory in medium and large companies in Ecuador, providing a standardized and robust framework for assessing psychosocial risks in various work environments and, crucially, for the present study.

The main objective of this study was to examine the relationship between psychosocial risk factors, measured specifically with the National Psychosocial Risk Assessment Questionnaire, and absenteeism in the manufacturing sector in Ecuador. Specifically, it aimed to identify, through multivariate analysis, which psychosocial dimensions of the national tool are significantly associated with absenteeism. In doing so, this study sought to provide robust empirical evidence from a Latin American context, inform organizational practices in the Ecuadorian manufacturing sector, and ultimately support the development of specific, evidence-based interventions to reduce absenteeism through the improvement of psychosocial working conditions.

2. METHODS

This study adopted a quantitative, descriptive, and correlational cross-sectional design. It sought to analyze the relationship between psychosocial risk factors and absenteeism in a specific manufacturing sector in Ecuador.

The target population comprised all eligible employees of the metalworking company INMEDECOR S.A., located in Quito, Ecuador. Inclusion criteria were full-time employees with at least three months of seniority; those on probation or with temporary contracts were excluded. The eligible population consisted of 60 workers across operational and administrative areas. All 60 agreed to participate (response rate = 100%), thus constituting a census of the target population.

In addition to the main study variables, basic sociodemographic data were collected from each participant, including age, gender, educational level, job title or area of work, and length of service at the company. This information was used to characterize the study population.

2.1. Psychosocial Risk Assessment

The assessment of psychosocial risk factors was carried out using the Psychosocial Risk Questionnaire of the Ecuadorian Ministry of Labor [22], a mandatory tool for companies with more than 10 employees in the country. This tool consists of 58 items organized into eight key dimensions: workload and work pace, development of competencies, leadership, margin for action and control, work organization, recovery, support and assistance, and other important points (e.g., workplace harassment, working conditions, double presence). Responses were formulated on a 4-point Likert scale, where “strongly agree” was scored as 4 and “disagree” as 1. Higher scores on the questionnaire indicate a lower perceived psychosocial risk (i.e., a more favorable psychosocial condition), and vice versa.

Although not directly derived from internationally recognized frameworks, such as the Job Content Questionnaire (JCQ) or the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire (COPSOQ), the Ecuadorian tool was designed to reflect the organizational, legal, and cultural realities of the country, while maintaining conceptual alignment with several of their dimensions. Importantly, a large-scale validation study involving 4,346 employees from 385 public and private organizations demonstrated excellent internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.967) and acceptable item–total correlations (r > 0.30), confirming its reliability and construct validity for the Ecuadorian workforce.

Its use in this study has been justified not only by its legal and institutional relevance in the local context but also by its capacity to capture psychosocial risk dimensions comparable to international instruments. This cultural specificity has reinforced the ecological validity of the findings, while the strong psychometric evidence has supported the robustness of the associations examined between psychosocial risks and absenteeism.

2.2. Assessment of Absenteeism

To quantify absenteeism, a consolidated database provided by the company was used, which recorded employee absences during the period between July 2023 and June 2024. It is important to note that absences due to vacations, scheduled suspensions, and leave (e.g., maternity/paternity or training) were excluded from the analysis, as they are not directly related to worker behavior or unscheduled psychosocial risk factors.

Absenteeism was calculated as the percentage of days absent for each employee in the last year, using Eq. (1) as follows:

2.3. Statistical Analysis

To evaluate the relationship between psychosocial risk dimensions (independent variables) and absenteeism (dependent variable) in the company, IBM SPSS Statistics 26 statistical software was used.

The assumptions of multiple linear regression were verified, including the linearity of the relationship between variables, the constant variance of errors, the normality of residuals, and the absence of significant multicollinearity among predictor variables.

The existence and strength of the relationship between the variables were evaluated using a multiple linear regression model. This model allowed us to determine the joint and individual impact of multiple independent variables on a dependent variable, assuming a functional relationship expressed by Eq. (2) as follows [23]:

Where,

• γn: dependent variable

• χ1…χn: independent variables

• β0: constant of the model

• β1β2β3β4: coefficients of each of the dimensions

• ϵ: error

The regression coefficients (β), their standard errors, the associated p-values, and the coefficient of determination (R2) were reported to evaluate the explanatory power of the model.

2.4. Ethical Considerations

This study primarily utilized secondary data provided by the participating manufacturing company, consisting of aggregated absenteeism records and fully anonymized responses from the National Psychosocial Risk Assessment Questionnaire.

| Work area | Administrative | 8 |

| Operative | 52 | |

| Sex | Female | 4 |

| Male | 56 | |

| Age | 25-34 years | 43 |

| 35-43 years | 14 | |

| 44-52 years | 3 | |

| Education level | Elementary school | 19 |

| High school degree | 28 | |

| Technical/technological | 8 | |

| College | 5 | |

| Time spent working in the company | 0-2 years | 14 |

| 3-10 years | 39 | |

| 11-20 years | 5 | |

| Equal to or more than 21 years old | 2 |

To maintain individual-level anonymity while enabling data linkage, the human resource department of the company internally performed a pre-coding process. Absenteeism data were provided to the research team in aggregate form, previously coded by the company using anonymous identifiers that prevented any direct or indirect identification of employees. The responses to the psychosocial risk questionnaire were linked to the absenteeism records by the company's internal staff prior to the anonymization process. In this way, the research team received only a consolidated database without personally identifiable information, ensuring confidentiality and compliance with national data protection regulations.

Ethical approval from an institutional review board or ethics committee was not required for this specific study, as researchers had no direct contact with employees or access to personally identifiable information at any stage of the research. Prior to data provision, informed consent for the use of anonymized data for research purposes was obtained from the company leadership, ensuring their agreement with the study's objectives and data handling protocols. This approach minimized any potential risk to individuals while maintaining the integrity and validity of the research findings.

3. RESULTS

Table 1 presents sociodemographic data of the study population. The sample consisted of 60 employees of INMEDECOR S.A., with 100% participation. Of the total, 93.3% were male, and the predominant age group was 25 to 34 years old (71.7%). Regarding educational level, 53.3% had secondary education. Lastly, 86.7% of the staff worked in operational areas.

3.1. Assessment of Exposure to Psychosocial Risk Factors

The results of the psychosocial risk assessment by dimension are detailed in Table 2. A high prevalence of risk was found across several dimensions, with high-risk levels notably present in recovery (20% of participants), double presence (25%), and workplace harassment (bullying) (1.7%). Additionally, a significant portion of the workforce perceived a medium level of risk in workload and work pace (83.3%) and margin of action and control (95%).

| Dimensions | Questionnaire Dimensions |

Low Risk (%) |

Medium Risk (%) |

High Risk (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Workload and work pace | 16.7 | 83.3 | 0.0 |

| 2 | Development of competencies | 55.0 | 45.0 | 0.0 |

| 3 | Leadership | 75.0 | 25.0 | 0.0 |

| 4 | Margin of action and control | 5.0 | 95.0 | 0.0 |

| 5 | Work organization | 98.3 | 1.7 | 0.0 |

| 6 | Recovery | 10.0 | 70.0 | 20.0 |

| 7 | Support and assistance | 8.3 | 91.7 | 0.0 |

| 8 | Other important points: | 98.3 | 1.7 | 0.0 |

| 8.1 | Discriminatory harassment | 53.3 | 46.7 | 0.0 |

| 8.2 | Workplace harassment (bullying) | 25.0 | 73.3 | 1.7 |

| 8.3 | Sexual harassment | 98.3 | 1.7 | 0.0 |

| 8.4 | Work addiction | 98.3 | 1.7 | 0.0 |

| 8.5 | Working conditions | 48.3 | 51.7 | 0.0 |

| 8.6 | Double presence (work–family) | 28.3 | 46.7 | 25.0 |

| 8.7 | Job and emotional stability | 53.3 | 46.7 | 0.0 |

| 8.8 | Self-perceived health | 88.3 | 11.7 | 0.0 |

| Work Area | Number of Employees | Number of Planned Hours | Number of Absent Hours | Absenteeism Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Administrative | 8 | 15120 | 211 | 1.40% |

| Operative | 52 | 114400 | 2780 | 2.43% |

| Total | 60 | 129520 | 2991 | 3.83% |

3.2. Assessment of Absenteeism

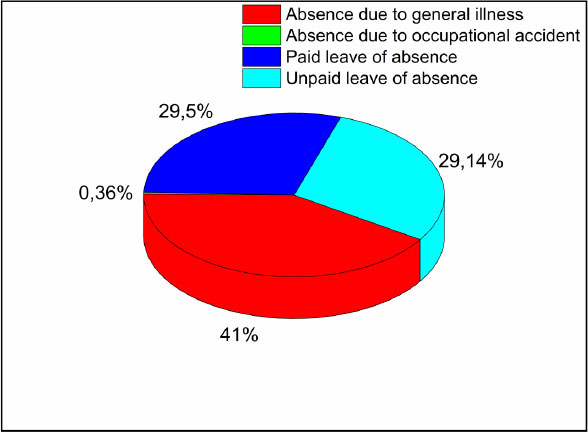

As shown in Table 3, the company recorded 2,991 hours of unscheduled absences between July 2023 and June 2024, corresponding to an absenteeism rate of 3.83%. The operational area had the highest number of absences, and the primary cause was general illness, which represented 41% of all cases (Fig. 1).

3.3. Statistical Analysis of the Relationship between Variables

As shown in Table 4, the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test revealed that both the psychosocial dimensions and the absenteeism rate exhibited a non-normal distribution (p<0.05). This finding justified the use of nonparametric and multivariate statistical tests for the analysis [24, 25].

Spearman's correlation coefficient (ρ) was used to evaluate the bivariate relationships between the absenteeism rate and the dimensions of psychosocial risk. As shown in Table 5, negative and statistically significant correlations (p < 0.01) were identified between absenteeism and four dimensions of psychosocial risk: double presence (work-family) (ρ = -0.810), workload and work pace (ρ = -0.749), recovery (ρ = -0.667), and workplace harassment (bullying) (ρ = -0.544). The negative β coefficients observed in the regression models should be interpreted as follows: as the perception of psychosocial conditions improves (higher scores, lower risk), absenteeism decreases. Conversely, lower scores (higher perceived risk) are associated with higher absenteeism rates. This clarification is critical to prevent any misinterpretation regarding the directionality of the regression coefficients. The remaining dimensions of the questionnaire did not show significant correlations with the absenteeism rate.

Proportion of causes of absenteeism from work.

| - | Kolmogórov-Smirnov | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Statistical | gl | Sig. | |

| Absenteeism rate | 0,139 | 60 | 0,006 |

| Workload and work pace | 0,169 | 60 | 0,001 |

| Development of competencies | 0,281 | 60 | 0,001 |

| Leadership | 0,227 | 60 | 0,001 |

| Margin of action and control | 0,482 | 60 | 0,001 |

| Work organization | 0,535 | 60 | 0,001 |

| Recovery | 0,141 | 60 | 0,005 |

| Support and assistance | 0,328 | 60 | 0,001 |

| Discriminatory harassment | 0,187 | 60 | 0,001 |

| Workplace harassment (bullying) | 0,267 | 60 | 0,001 |

| Sexual harassment | 0,427 | 60 | 0,001 |

| Work addiction | 0,171 | 60 | 0,001 |

| Working conditions | 0,290 | 60 | 0,001 |

| Double presence (work–family) | 0,271 | 60 | 0,001 |

| Job and emotional stability | 0,188 | 60 | 0,001 |

| Self-perceived health | 0,315 | 60 | 0,001 |

| Absenteeism Rate | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Rho de Spearman | Absenteeism rate | Correlation coefficient | 1,000 |

| Sig. (bilateral) | |||

| N | 60 | ||

| Workload and work pace | Correlation coefficient | -0,749** | |

| Sig. (bilateral) | 0,000 | ||

| N | 60 | ||

| Development of competencies | Correlation coefficient | -0,147 | |

| Sig. (bilateral) | 0,262 | ||

| N | 60 | ||

| Leadership | Correlation coefficient | -0,205 | |

| Sig. (bilateral) | 0,116 | ||

| N | 60 | ||

| Margin of action and control | Correlation coefficient | -0,105 | |

| Sig. (bilateral) | 0,425 | ||

| N | 60 | ||

| Work organization | Correlation coefficient | 0,094 | |

| Sig. (bilateral) | 0,474 | ||

| N | 60 | ||

| Recovery | Correlation coefficient | -0,667** | |

| Sig. (bilateral) | 0,000 | ||

| N | 60 | ||

| Support and assistance | Correlation coefficient | -0,240 | |

| Sig. (bilateral) | 0,065 | ||

| N | 60 | ||

| Discriminatory harassment | Correlation coefficient | -0,077 | |

| Sig. (bilateral) | 0,558 | ||

| N | 60 | ||

| Workplace harassment (bullying) | Correlation coefficient | -0,544** | |

| Sig. (bilateral) | 0,000 | ||

| N | 60 | ||

| Sexual harassment | Correlation coefficient | 0,204 | |

| Sig. (bilateral) | 0,118 | ||

| N | 60 | ||

| Work addiction | Correlation coefficient | 0,119 | |

| Sig. (bilateral) | 0,127 | ||

| N | 60 | ||

| Working conditions | Correlation coefficient | -0.048 | |

| Sig. (bilateral) | 0.717 | ||

| N | 60 | ||

| Double presence (work–family) | Correlation coefficient | -0,810** | |

| Sig. (bilateral) | 0,000 | ||

| N | 60 | ||

| Job and emotional stability | Correlation coefficient | 0,031 | |

| Sig. (bilateral) | 0,816 | ||

| N | 60 | ||

| Self-perceived health | Correlation coefficient | -0,162 | |

| Sig. (bilateral) | 0,217 | ||

| N | 60 |

A multiple linear regression model was developed to estimate the combined influence of the significantly correlated dimensions on absenteeism. The initial model included the four dimensions that showed significant correlations in Spearman's analysis: workload and work pace, recovery, workplace bullying, and double presence (work-family). The results of the model summary are presented in Table 6 and the corresponding regression coefficients in Table 7.

The multiple correlation coefficient, R = 0.886, indicated a strong relationship between the predictor variables and the absenteeism rate. A value close to 1 suggested a strong linear relationship [26]. The coefficient of determination (R squared = 0.785) suggested that 78.5% of the variability in the absenteeism rate can be explained by the psychosocial risk dimensions included in this model, whose value also reflected a good fit of the model. The adjusted R-squared (0.769) confirmed a good fit of the model. The low standard error (0.6144%) indicated accuracy in the estimates.

The results in Table 7 indicate that the dimensions workload and pace (B = -0.339, p<0.001), recovery (B = -0.159, p<0.001), and double presence (work-family) (B = -0.384, p<0.001) showed negative and statistically significant coefficients. Consistent with the scale's interpretation established previously, these negative coefficients confirmed a better perception of psychosocial conditions (higher scores, lower risk) to be associated with a decrease in the absenteeism rate. In contrast, the dimension workplace harassment (bullying) was not statistically significant (B = -0.098, p=0.488) in this initial model.

An adjusted multiple linear regression analysis was performed, excluding the dimension of workplace harassment (bullying). The results of this adjusted model are presented in Table 8 (model summary) and Table 9 (coefficients).

| Model | R | R square | Adjusted R-squared | Standard Error of Estimation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0,886a | 0,785 | 0,769 | 0,6144% |

b. Dependent variable: absenteeism rate

| Model | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | t | Sig. | 95.0% Confidence Interval for B | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Desv. Error | Beta | Lower Limit | Upper Limit | ||||

| 1 | (Constant) | 10,675 | 0,817 | 13,063 | 0,001 | 9,037 | 12,312 | |

| Workload and work pace | -0,339 | 0,074 | -0,396 | -4,606 | 0,001 | -0,487 | -0,192 | |

| Recovery | -0,159 | 0,046 | -0,272 | -3,412 | 0,001 | -0,252 | -0,065 | |

| Workplace harassment (bullying) | -0,098 | 0,141 | -0,057 | -0,698 | 0,488 | -0,380 | 0,184 | |

| Double presence (work–family) | -0,384 | 0,110 | -0,342 | -3,499 | 0,001 | -0,603 | -0,164 | |

| Model | R | R Square | Adjusted R-Squared | Standard Error of Estimation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0,885a | 0,783 | 0,771 | 0,612% |

b. Dependent variable: absenteeism rate

| Model | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | t | Sig. | 95.0% Confidence Interval for B | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Desv. Error | Beta | Lower Limit | Upper Limit | ||||

| 1 | (Constant) | 10,302 | 0,615 | 16,743 | 0,000 | 9,069 | 11,535 | |

| Workload and work pace | -0,331 | 0,072 | -0,386 | -4,574 | 0,000 | -0,476 | -0,186 | |

| Recovery | -0,168 | 0,044 | -0,288 | -3,802 | 0,000 | -0,257 | -0,080 | |

| Double presence (work–family) | -0,418 | 0,097 | -0,373 | -4,295 | 0,000 | -0,613 | -0,223 | |

The adjusted model (Table 8) yielded an R-squared value of 0.783 and an adjusted R-squared value of 0.771, indicating that the remaining three dimensions accounted for approximately 77.1% of the variability in the absenteeism rate. The coefficients in Table 9 confirm that workload and pace, recovery, and double presence (work-family) remained significant and negative predictors of absenteeism. Taken together, these factors explained a substantial proportion of the variance in absenteeism within the studied context.

Based on the B coefficients and the constant provided in Table 9, the equation of the adjusted multiple linear regression model is given as Eq. (3):

4. DISCUSSION

The results of this study showed psychosocial factors to have a significant association with work absenteeism among workers at the metalworking company analyzed. This relationship was supported by multivariate statistical models, which indicated dimensions, such as workload and work pace, recovery, and double presence (work-family), to be significant predictors of absenteeism behavior, thus confirming the objective proposed in this work.

The results of the psychosocial risk assessment (Table 2) identified recovery (20% high risk) and double presence (work-family) (25% high risk) as the dimensions with the highest level of risk among INMEDECOR S.A. employees. These findings have been found to be particularly concerning in a manufacturing sector characterized by high physical demands and rigid schedules [10], which can make it difficult to disconnect from work and balance personal and work responsibilities [27]. The perception of insufficient recovery from work-related stress, coupled with the tensions of balancing personal and professional spheres, is a known factor contributing to burnout and chronic stress [28, 29]. This suggests that, although the questionnaire measures risk perception, a high-risk score in these dimensions implies that employees feel they cannot recover adequately or that their work and family life are in conflict, which is detrimental to their well-being.

The workload and work pace, as well as the margin for action and control, did not reach a high-risk level; however, they showed a considerable proportion of employees at “medium” risk (83.3% and 95.0%, respectively). This highlights the constant production pressure and limited autonomy often inherent in manufacturing environments [7]. As pointed out by Mansor et al. [30], a well-managed workload is crucial for work-life balance, while an excess can lead to conflicts and affect mental and physical health, impacting productivity and engagement.

With regard to absenteeism, the overall rate of 3.83% at INMEDECOR S.A. is an important indicator. The differences observed between the administrative area (1.40%) and the operational area (2.43%) suggest that the particularities of the work environment and the demands of each area may influence absenteeism patterns. The higher prevalence of absences in the operational area could be linked to greater physical demands, the repetitive nature of tasks, and exposure to risks inherent to the sector [9, 10].

An analysis of the causes of absenteeism (Fig. 1) revealed general illness as the main reason for absence (41%). While many illnesses may not be directly related to the work environment, their high prevalence underscores the need for health and wellness promotion programs in the workplace, given that general health is influenced by multiple factors, including physical activity, which has been shown to reduce absenteeism [31, 32]. The high proportions of unpaid leave (29.14%) and paid leave (29.50%) highlighted the need for work-life balance and the importance of flexible policies. Chungo and Anyieni [33] emphasize that employees need time for personal and family matters, and the implementation of paid leave can improve satisfaction and productivity [34]. The low percentage of absences due to work-related accidents (0.36%) is a positive indicator of the effectiveness of the safety measures implemented in this metalworking company.

The results of Spearman's correlation analysis (Table 5) established significant relationships between absenteeism and various psychosocial dimensions. Specifically, significant negative correlations were found between the absenteeism rate and workload and work pace (p = −0.749), recovery (p = −0.667), workplace harassment (bullying) (p = −0.544), and double presence (work-family) (p = −0.810). It is important to interpret these negative correlations in the context of the questionnaire: a higher score on the dimension (which, according to the instrument, indicates a lower perception of risk or a more favorable situation in that dimension) is associated with a lower absenteeism rate. These findings are consistent with the vast literature that has linked adverse psychosocial factors (such as high workload, lack of recovery, harassment, and work-life imbalance) with increased absenteeism [35-37].

The adjusted multiple linear regression model (Tables 8 and 9) confirmed and deepened these findings, demonstrating workload and work pace, recovery, and double presence (work-family), together, to explain a substantial 77.1% of the variability in the absenteeism rate. This underscores that absenteeism is not a random event, but a direct and significant consequence of psychosocial conditions in the work environment.

The interpretation of the negative regression coefficients in the adjusted model was consistent with the correlations. The workload and work pace coefficient (B = -0.331) indicated that when employees perceive less overload or experience a more manageable work pace, absenteeism decreases. This has been found to be consistent with the findings of Tentama et al. [38], who linked high workload and lack of control to increased stress and absenteeism. Similarly, the recovery coefficient (B = -0.168) suggested that greater opportunity for rest and disconnection is associated with lower rates of absence, as supported by the study of Kim et al. [28] on the role of recovery in mitigating stress and tension.

The dimension with the most significant predictive weight in the model was dual presence (work-family) (B = -0.418). This finding has been found to be particularly relevant, indicating that a better balance between work and family responsibilities is a key factor in reducing absenteeism. This aligns with social exchange and reciprocity theory, where employees respond positively to organizational benefits, such as work-life balance policies, which improve job satisfaction and reduce behaviors, such as absenteeism [39, 40]. Thus, a healthy work-life balance not only benefits the employee but also fosters their commitment and reduces absences.

Finally, although workplace harassment (bullying) showed a significant correlation in the bivariate analysis, it did not maintain its significance in the multiple regression model. This suggests that, while harassment may be an influential factor in itself, its impact on absenteeism in this sample could be mediated or less direct when other psychosocial dimensions with greater predictive weight are considered simultaneously.

4.1. Study Limitations

This study has presented several methodological limitations that should be acknowledged.

Its cross-sectional design restricted the ability to establish causal relationships between psychosocial risk factors and absenteeism. The associations observed should therefore be interpreted as correlations rather than cause-and-effect dynamics.

Additionally, the study was conducted in a single metalworking company (a case study), limiting the generalizability of the findings to other organizations or industrial sectors. Although the company represented typical working conditions in Ecuador’s manufacturing context, the results should be viewed as case-specific evidence.

Furthermore, while the use of the National Psychosocial Risk Assessment Questionnaire strengthens the local validity and standardization of the measurements, its self-reported nature may introduce response bias, as participants might under- or overestimate certain psychosocial dimensions.

Finally, absenteeism data, though obtained from objective company records, were analyzed only in aggregate form (as a rate). This limitation prevented a deeper exploration of individual trajectories or the role of potential moderating variables, such as age, tenure, or specific job position, which warrants investigation in future studies.

4.2. Recommendations

The strong predictive power of the established model (77.1% of variance explained) highlights the need for an integrated intervention program within the studied organization and comparable manufacturing entities. This program should specifically address the three significant dimensions [workload and work pace, recovery, and double presence (work–family conflict)] through evidence-based organizational policies. Practical measures include the redistribution of tasks to prevent work overload, the promotion of micro-breaks and digital disconnection to enhance recovery, and the implementation of flexible scheduling and family-supportive initiatives to alleviate work-family conflict. Strengthening leadership training to identify early signs of psychosocial strain can further sustain employee well-being and reduce absenteeism.

From a research perspective, future studies should adopt longitudinal or pre-post intervention designs across multiple industrial sites to establish causal relationships and measure the real impact of psychosocial interventions. Additionally, incorporating moderating variables, such as age, gender, and tenure, will refine the understanding of absenteeism dynamics and improve the precision of targeted organizational actions.

CONCLUSION

Psychosocial risk factors have been found to have a statistically significant association with work absenteeism in the metalworking company analyzed. The dimensions of workload and work pace, recovery, and double presence (work-family) were the most relevant, both in terms of their level of risk and their correlation with annual records of absences.

Multivariate analysis showed workers with negative perceptions in several psychosocial dimensions to be more prone to absenteeism, reinforcing the usefulness of complex statistical approaches for understanding multifactorial phenomena in the organizational setting.

The dimensions of recovery and double presence (work-family) were identified as representing the highest levels of psychosocial risk perceived by employees. This highlights the difficulty of effectively disconnecting from work and balancing work demands with personal responsibilities, factors that are critical in industrial environments with high demands and structured schedules.

Statistical analysis revealed workload and work pace, recovery, and double presence (work-family) to be significant predictors of absenteeism. Together, these three dimensions accounted for approximately 77% of the variability observed in absenteeism within this company.

However, given the cross-sectional design and the single-site sample, these findings should be interpreted as case-specific associations rather than generalizable causal relationships. Future research should extend this analysis to larger and more diverse samples to confirm these patterns and guide evidence-based interventions for improving psychosocial working conditions and reducing absenteeism.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: J.D.I.L.: Study conception and design; D.J.L.Q.: Methodology; E.V.Y.C.: Data collection. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| OIT | = International Labor Organization |

| EU-OSHA | = European Agency for Safety and Health at Work |

| IWH | = Institute for Work and Health |

| JCQ | = Job Content Questionnaire |

| COPSOQ | = Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire |

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Informed consent was obtained from the collaborating company's leadership before the provision of data.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors gratefully acknowledge the institutional support and facilities provided by the Universidad Técnica Particular de Loja for the successful completion of this research study.

AI TOOL DISCLOSURE

The authors declare that ChatGPT (GPT-4), developed by OpenAI, was used exclusively for editing and improving the grammar and fluency of the manuscript. This tool was not used in the study design, data collection, analysis, or interpretation. Responsibility for the content and conclusions expressed in this manuscript rests entirely with the authors.