SYSTEMATIC REVIEW

Interventions to Promote Rehabilitation Programmes for Youth with Violent Behaviours in Limpopo Province: A Systematic Literature Review

Tshilidzi O. Ramakulukusha1, *, Sunday S. Babalola2, Ntsieni S. Mashau1

Article Information

Identifiers and Pagination:

Year: 2022Volume: 15

E-location ID: e187494452202031

Publisher ID: e187494452202031

DOI: 10.2174/18749445-v15-e2202031

Article History:

Received Date: 17/7/2021Revision Received Date: 9/11/2021

Acceptance Date: 17/12/2021

Electronic publication date: 01/04/2022

Collection year: 2022

open-access license: This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Public License (CC-BY 4.0), a copy of which is available at: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/legalcode. This license permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Background:

A rehabilitation strategy aims to reshape the individual and prepare them to enter society with a different state of mind and start a new life after incarceration.

Objective:

The purpose of this systematic literature review was to identify and describe the intervention strategies to promote rehabilitation programmes for youth with violent behaviours, guided by Rodger’s evolutionary concept analysis framework.

Methods:

A comprehensive database search was conducted from 2010 to 2020. The review focused on quantitative and qualitative studies and reports obtained from GOOGLE SCHOLAR, SABINET, SAGE, EBSCO-HOST, and SCIENCE DIRECT. Keywords and search strategies were also taken into consideration. The researchers systematically reviewed the literature, and 250 articles and 25 reports were obtained; their content was screened for relevance, and 50 articles and 11 reports were found to be suitable and relevant; these were then reviewed. A thematic analysis was performed to identify antecedents, attributes, and consequences of rehabilitation on youth with violent behaviours. The study findings were then used to inform the development of the conceptual framework.

Results:

The results show that antecedents of these rehabilitation strategies on violent youth behaviours include family structure, increased bullying due to gangs, and gender and environmental factors. The identified attributes were motivation, contextual differences, transformation, opportunity, and ineffective rehabilitation programmes in addressing violent behaviours in youths.

Conclusion:

Youth is regarded as the most vulnerable group in society, holding a high percentage of the population. As a result, it is always vital to protect them.

1. INTRODUCTION

Youth violence is a significant public health problem that affects thousands of young people each day, and in turn, their families, schools, and communities. David-Ferdon et al. [1] report that youth violence occurs when young people between the ages of 10 and 24 intentionally use physical force or power to threaten or harm others. The same authors allude that youth violence can take different forms, including fights, bullying, threats with weapons, and gang-related violence. As a result, a young person can be involved in violence as a victim, offender, or witness.

Worldwide, several prevention strategies have been implemented to improve youth violent behaviours outcomes, such as rehabilitation strategies that play a major role in addressing youth violence. However, despite the availability of those strategies, violent youth behaviours continue to increase. Rehabilitation is defined as a process or a set of processes that are planned and are limited in time, having well-defined goals and means, of which professionals or services co-operate in assisting the individual user in their efforts to achieve the best possible functioning and coping capabilities and promoting independence and participation in society [2].

In literature, statistical data in many countries show that delinquency is essentially a group phenomenon. Between two-thirds and three-quarters of all offences committed by young people are committed by members of gangs or groups, which can vary from highly structured criminal organisations to less structured street gangs. It is further reported that even those young people who commit offences alone are more likely to be associated with groups. Youth violence is regarded as a severe challenge to the family, public safety, the lives of young people themselves, and law enforcement agencies [3]. Therefore, strategies are defined as plans designed and implemented to attain goals or objectives to achieve a long-term aim [4].

The Limpopo Province of South Africa is a largely rural province, with more than 87% of people in the province living in rural areas [5]. Limpopo is one of the provinces with a high rate of unemployment among young people. It is one of the most underdeveloped areas in South Africa; the province is made up of five district municipalities and 25 local municipalities [5]. The reasons for the increase in unemployment in this province are numerous. Still, the main one is that the formal sector of the economy has not been able to create enough job opportunities for its growing labour force.

Approximately 17% of the inhabitants of the province do not have a formal education. Inhabitants of Limpopo are employed by public sector institutions and the mining, trade, and agricultural sectors [5]. This study included two child and youth care centres (Bosasa-Mavambe) in the Vhembe District and (Bosasa-Polokwane) in the Capricorn District. The study was conducted to develop strategies to promote the implementation of rehabilitation programmes for youth in child and youth care centres in the Limpopo Province.

2. PURPOSE

The purpose of this systematic literature review is to identify and describe the interventions and strategies to promote rehabilitation programmes for youth with violent behaviours, guided by Rodger’s evolutionary concept analysis framework. The study further aims to develop a Conceptual framework (CF) that would guide research on interventions to promote rehabilitation programmes for youth with violent behaviours in the Limpopo province.

The study was conducted based on the assumptions that dysfunctional families, the influence of delinquent peers, substance misuse, and gangsterism may influence the involvement of youth towards violent behaviours. This study seeks to add to the literature on the intervention strategies meant to promote the rehabilitation programmes for youth with violent behaviours in the Limpopo Province. Thus, it will pay attention to the factors to prevent youth offences and the factors that will improve positive outcomes of rehabilitation programmes. Moreover, the study will enlighten the youth’s parents/guardians to take their full responsibility towards raising and providing for the basic needs of their children.

3. METHODS

3.1. Rodger’s Concept Analysis Framework

Rodger’s evolutionary concept analysis framework will guide this study. Rodger highlights that concepts develop over time and are influenced by the context in which they are used [6, 7]. He further argues that these concepts are constantly undergoing dynamic development, which redefines the analysis of a concept and related terms such as antecedents, attributes, and consequences. Antecedents are events that occur prior to a concept and influence the evolution of that concept; attributes are defined as characteristics of that specific concept in terms of addressing its intended issue; and consequences are the results of the concepts, which help in clarifying them more clearly [8, 9].

A total of 275 articles and reports were identified but after rigorous screening only 61 met the inclusion criteria. The studies were conducted between 2010 and 2020. The majority of the studies (n=13) were carried out in South Africa, United States of America (n=09), Iran (n=03), Turkey (n=03), China (n=02), Pakistan (n=02), Malaysia (n=02), Netherlands (n=02), Philippines (n=02), India (n=02), Nigeria (n=02), Ghana (n=02), Zimbabwe (n=01), Lesotho (n=01), Saudi Arabia (n=01), Angola (n=01), Kenya (n=02), Sweden (n=01), Israel (n=01), Philadelphia (n=01), Latin America (n=01), Los Angeles (n=01), Canada (n=01), Australia (n=01), United Kingdom (n=02), Brazil (n=01), and Spain (n=01).

Most of the studies (n=45) utilised a quantitative design, followed by some (n=16) that used a qualitative design. The majority (n=19) of the programmes were delivered in institutions, followed by school-based programmes (n=18), community-based studies (n=17), and lastly, family-based programmes (n=07).

3.2. Collection and Analysis of Data

3.2.1. Inclusion Criteria

In this systematic review, studies were included if they met the following criteria.

- Population: This study targets the youth considered to be young individuals under the age of 35. Therefore, all the articles that targeted these young people were included.

- Study setting:This work includes all the studies conducted in institutions/correctional facilities, families, schools, and community-based settings.

- Type of study: All studies such as qualitative, quantitative, mixed methods, randomised control trials, and quasi-experimental studies were included. Studies carried out all over the world have been included.

- Language of the publication: Peer-reviewed and Gray literature written only in English were included.

- Time period: All studies from 2010 to 2020 were included in this study.

- Other data All studies on rehabilitation programmes implemented from 2010 to 2020 that targeted young people meant to prevent violent behaviours were included.

The selected articles and reports had to pass the quality assessment criteria described in Table 1.

| Study | Setting & Country | Study Objectives | Study Design | Outcomes/Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Institutional Based Studies | ||||

| 1. Mantey EE, Dzetor G. Juvenile Delinquency: Evidence of Challenges in Rehabilitation. J Appl Sciences 2013; 15(6): 321-330. [3] | The juvenile detention centre, Ghana | To explore the procedure used in admitting inmates into juvenile detention facilities and challenges in rehabilitating them and recommend strategies based on findings to improve the rehabilitation system. | Quantitative Study. | -The findings indicated challenges that affect both caretakers and inmates at the centre regarding human resources, inadequate training period, facility to house inmates, and the proper procedure for admission into the correctional facility. -These challenges showed gaps in the rehabilitation process whose mission is to make delinquent children valuable members of society after they are released. Instead, many juvenile delinquents stand a high risk of becoming criminals in their adulthood. |

| 2. Gwatimba L, Raselekoane NR. An Evaluation of the Effectiveness of Diversion Programmes in the Rehabilitation of the youth and the promotion of Juvenile Justice in South Africa. J Gen & Behaviour 2018; 16(1): 11168 – 1118. [24] | Youth development centres, SA | -To evaluate the effectiveness of diversion programmes in the rehabilitation of the youth and promoting juvenile justice in South Africa. | Qualitative study. | -The study revealed that some young people continue to display antisocial behaviour even after being exposed to diversion programmes. -Follow-up services and tracking the young people during their reintegration into their communities would discourage them from sliding back into anti-social behaviour. |

| 3. Seyyed-Mohammad et al. A Behavioural Intervention for Changing the Attitude of Young Boys in Iranian Juvenile Detention Centres. Iran Rehabil Journal 2019; 17(3): 241-252. (Research Article) | Juvenile detention centres, Iran. | -For changing the attitudes of juveniles in conflict with the law. | Quasi-experimental study | -The efficiency of the model was evaluated. This model is effective in improving knowledge and skills and changing the attitude of delinquent juveniles. -Based on the findings of this study, a model was designed, using three principles of the Red Cross society, basic life skills, and first aid skills that can be effective in changing the attitudes and behaviour of people in juvenile detention centres. |

| 4. Reingle et al. A case-control study of risk and protective factors for incarceration among urban youth. J Adol Health 2013; 53(4): 471-477. (Research Article) | Correctional facility & school-based, USA | To examine the early risk factors for incarceration using a high-risk sample of urban youth. | Quantitative study | -The early risk factors for incarceration were age, having been sent to detention, the number of hours spent participating in a sport. |

| 5. Obioha, E.E. and Nthabi, A.M. Social Back-ground Patterns and Juvenile Delinquency Nexus in Lesotho: A Case Study of Juvenile Delinquents in Juvenile Training Centre (JTC), Maseru. Journal of Social Sciences.2011; 27(3): 165-177. https://doi.org/10.1080/09718923.2011.11892917. (Research Article) |

The juvenile training centre, Lesotho. | To investigate the social background patterns of juvenile delinquents to ascertain their contributions to juvenile delinquencies in Lesotho. | Quantitative study | Most delinquents come from broken homes; most delinquents are males; delinquency is higher in urban areas than in rural areas. Most delinquents are part of peer groups who engage in delinquent behaviours. Precisely, Maseru, the capital city of Lesotho and Leribe, were the districts with the highest rates of juvenile delinquency. It was also discovered that most of the juveniles have fathers who are employed in the mining industry. -The most committed offence across the country was robbery. The high rates of robbery, housebreaking, and stock theft indicate that poverty may be the factor behind the scene in Lesotho, which requires urgent attention from the government to tackle and eradicate poverty. |

| 6. Mambende et al. Factors Influencing Youth Juvenile Delinquency at Blue Hills Children’s Prison Rehabilitation Centre in Gweru, Zimbabwe: An Explorative Study. Int Jour Human Social Science and Education 2016; 3(4): 27-34. (Research Article) | Detention centre, Zimbabwe | To explore the factors influencing youth juvenile delinquency at Blue Hills Children’s Prison Rehabilitation Centre in Gweru. | Qualitative study | -Results indicated that juvenile delinquency was influenced by lack of parental attachment, broken homes, the authoritative parenting style, and poverty. It was concluded that the family and home environment greatly influence a child’s development and subsequently create a delinquent predisposition. |

| 7. Azade et al. Adolescent Female Offenders’ Subjective Experiences of How Peers Influence Norm-Breaking Behaviour. Chil and Adol Soc work Journal 2018; 35(1): 257–270. (Research Article) | The youth detention centre, Sweden |

To explore how young female offenders described their delinquent behaviours and, more specifically, their role in peer relations in committing or avoiding delinquent acts. | Qualitative study | -The finding was that the female offenders showed an awareness of the importance of pro-social peers and the need to eliminate delinquent friends from their peer network to help them refrain from deviant behaviours. |

| 8. Alamgir et al. Explore the factors behind Juvenile delinquency in Pakistan: A research conduct in juvenile jail of Rawalpindi, Pakistan. Int Jour of Scien & Engin Research 2018; 9(3): 1086-1091. (Research Article) | The juvenile detention centre, Pakistan |

-To identify the characteristics of juvenile delinquency, investigate psychological reasons for juvenile delinquency, and investigate the relationship between socio-economic instability and juvenile delinquency. | Quantitative study | -The following factors may be included: Socialisation, psychological factors, parental responsibilities, educational background, societal framework, economic conditions, and many other factors that motivate them to do so for the crime. |

| 9. Rathinabala I, Naaraayan SA: Effect of family factors on juvenile delinquency. Int Jour Cont Paediatrics’ 2017; 4(6): 2079-2082. (Research Article) | Adolescents detention centres and schools, India. | -To determine the effect of family factors on juvenile delinquency. | Randomised Control Trial | -Paternal age of more than 50 years, paternal smoking, maternal employment, and the single parent are significant independent risk factors of juvenile delinquency. |

| 10. Abella JL: Extent of the Factors Influencing the Delinquent Acts among Children in Conflict with the Law. J Chil and Adol Behaviours 2015; 4 (2): 1-4. (Research Article) | Children institution, Philippines | -To determine the influence of several factors in the commission of delinquent acts among children in conflict with the law. | Quantitative study. | This study found that external factors, including the environment outside the home, peer pressure, and community rule, greatly influence the lives of children in conflict with the law. -This study further holds that there has been a strong positive relationship between the internal factors and the external factors identified, which thereby influenced the respondents to commit delinquent acts |

| 11. Basson P, Mawson P. The Experience of Violence by Male Juvenile Offenders Convicted of Assault: A Descriptive Phenomenological Study. Indo-Pac Jour Phenomenology 2011; 11(1): 1-10. (Research Article) | The juvenile detention centre, SA. | To describe the experience of violence by male juvenile offenders convicted of assault to gain a deeper understanding of this phenomenon. | Qualitative study. | -The researchers found that the phenomenon of violence is characterised by the juveniles’ experience of external events that provoke a specific response manifesting itself in violent behaviour. -The responses described by the participants were primarily emotional and included emotions such as anger, rage, and fury. |

| 12. Ahmad Badayai et al. An exploratory study on symptoms of problem behaviours among juvenile offenders. J Psychology 2016; 30 (1): 69-79. (Research Article) | Juvenile institutions, Malaysia | To examine different types of symptoms of problem behaviours among juvenile offenders. | Quantitative study | -The results showed there were different symptoms of problematic behaviours among young offenders. Gender differences profile also showed mean differences in each symptom of problematic behaviours among juvenile offenders. -One-way ANOVA results showed significant differences in thought problem F (7) = 2.748, p< .01 and attention problem F (7) = 25.948, p < .01 among different types of delinquent behaviours. Moreover, t-test results revealed that gender differences were significant in social problem; t (402) = -2.710, p<.01, thought problems; t (402) = -2.476, p<.05, attention problem; t (402) = -4.841, p<.001, and aggressive behaviour; t (402) = -3.165, p<.001, p< .01. |

| 13. Matshaba TD. Risk-taking behaviour among incarcerated male offenders in South African Youth correctional centres. Sou Afri J of Criminology 2014; (1): 40-5 2. (Research Paper) | Youth Correctional Centre, SA. | -To establish and explore the youth tendencies and motivation to be involved in risky activities within correctional centres | Qualitative study. | -The results reveal that a significant number of inmates recognise that sexual activity is the highest form of risky behaviour inside correctional centres. The results also revealed that gang activities are rated as high-risk behaviour in youth correctional centres because inmates affiliate with various gangs to protect themselves against possible violations from other inmates. |

| 14. Ruigh et al. Predicting quality of life during and post detention in incarcerated juveniles. Quality of life research 2019; (28): 1813 -1823. (Research Paper) | Juvenile Justice Institutions, Netherlands |

To describe and predict QoL of detained young offenders up to 1 year after an initial assessment and examine whether QoL differs between youth who are still detained versus released. | Quantitative study | -Methods incorporating trauma-sensitive focus and relaxation techniques in treatment protocols in juvenile justice institutions may be of added value in improving the general functioning of these individuals. |

| 15. Milani et al. Effectiveness of Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT) in Reducing Aggression of Individuals at the Juvenile Correction and Rehabilitation Center. Int J of High-Risk Beh Addictions 2013; 2(3):126-31. (Research Article) | Juvenile Correction and Rehabilitation Centre, Iran | -The present study investigates the effectiveness of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy training (MBCT) in reducing aggression. | Quantitative study | -The results of ANCOVA showed that mindfulness-based cognitive training could significantly reduce aggression during post-test and follow-up test phases in the experimental group, compared to the control group (P < 0.01). According to the results of the present study, mindfulness-based cognitive training seems to be effective for reducing aggressive behaviours. |

| 16. Mbiriri M. To establish the relationship between sociodemographic characteristics and conduct disorder among girls incarcerated at Kirigiti and Dagoretti Rehabilitation Schools in Kenya. Int J of Soc Scie and Econ Research 2017; 02(08): 4147-4166. (Research Article) | Rehabilitation schools, Kenya | -To establish the relationship between sociodemographic characteristics and conduct disorder among girls incarcerated at Kirigiti and Dagoretti rehabilitation schools. | Quasi-experimental study | -The study suggests that the risk factors for adolescents in conflict with the law include poor socio-demographic status and psychological impacts of divorced parents. Negative peer group pressure was also a risk factor for incarcerated adolescents. These agreed with several studies that have found a consistent relationship between involvement in delinquent behaviours among girls and socio-economic background. It suggests that the factors need to be addressed in efforts to understand and address delinquency in girls. |

| 17. Alnasir FA, Al-Falaij AA. Factors Affecting Juvenile Delinquency in Bahrain. J of Gen Practice. 2016; 4(1):1-5. (Research Article) | Juvenile centre, Saudi-Arabia |

-To find out the factors that affect the juveniles in Bahrain. | Quantitative study | -The results indicate that there are relationships between juvenile delinquency and parental demographic characteristics. More delinquent subjects had illiterate fathers (47%) (p<0.05) and mothers (67%), (p<0 .001) than non-delinquent subjects. Fifty percent (n=15) of the non-delinquent subjects reported that their fathers were professional versus 21% of the delinquents (p<0.05). The familial relationships, conflicts, and practices were also related to the presence of delinquency |

| 18. Ntuli NP. Exploring Diversion Programmes for Youth in Conflict with the Law: Case Studies of the Youth Empowerment Scheme Programme at NICRO. 2017; Durban, South Africa. University of Kwazulu-Natal. Master of Social Sciences and Criminology. (Unpublished Dissertation) | Nicro-Institution, SA. | -To establish whether the youths’ understanding of their criminal behaviour had changed after completing the program to identify factors contributing to their criminal behaviour. | Qualitative study | Despite some success in reducing crime among youth who conflicted with the law by rehabilitating them in diversion programmes, some youth find it difficult to live their lives in harmony with the behavioural norms of their society and are often tempted to deviate due to their circumstances. -The illumination of the perspectives and understanding of youth is limited in the literature. However, much work has been done in recent years through diversion programmes. Efforts have been made to determine the effectiveness of diversion programmes |

| 19. Cole B, Chiphaca A. Juvenile delinquency in Angola. J of Crim & Criminal Justice 2014; 14(1): 61 –76. (Research Article) | Juvenile observation centre, Angola | -To explain these children’s offences based on their accounts of what they claimed was responsible for their offending behaviour. | Quantitative study | -The study indicates ways to address this problem; a proactive approach is required in Angola that supports youth, prevents violence, and enables sustainable neighbourhood development. |

| Family-Based Studies | ||||

| Setting & Country | Study Objectives | Study Design | Outcomes/Findings | |

| 20. De Vries et al. Practitioner Review: Effective ingredients of prevention programs for youth at risk of persistent juvenile delinquency recommendations for clinical practice. J Chil Psych and Psychiatry 2015; 56 (2): 108–121. (Research Article) | Family-based, Netherlands | -To examine the effectiveness of programs in preventing persistent juvenile delinquency and by studying which particular programme, sample, and study characteristics contribute to the effects. | Quasi-experimental study | -Prevention programs have positive effects on preventing persistent juvenile delinquency. In improving programme effectiveness, interventions should be behaviour-oriented, delivered in a family or multimodal format, and the intensity of the program should be matched to the level of risk of the juvenile. |

| 21. Lutya TM. The Importance of a Stable Home and Family Environment in the Prevention of Youth Offending in South Africa. Int J of Crim and Sociology 2012; 1(3): 86-92. (Research Article) | Family-based, SA. | -To present a strategy to prevent youth offending in South Africa. | Qualitative study | This paper argues that South Africa should consider the importance of a stable home and family environment to prevent youth offending. -Firstly, family planning is essential. Secondly, parental involvement in a child’s activities is vital to ensure proper supervision and monitoring. -Thirdly, in the absence of adequate parenting skills, efficacy and management parenting programmes could help parents learn a conforming manner of rearing their children. -Lastly, once they have been caught committing a crime, parents ought to take centre stage to ensure the child’s behavioural transformation. |

| 22. Chauke TA, Malatji KS. Youth experiences of deviant behaviours as portrayed in some television programmes: A case of the youth of 21st century. J of Gen & Behaviours 2018; 16(3): 12178 – 12189. (Research Article) | Family-based, SA. | -To explore how the portrayal of deviant behaviour in selected television programmes influences the youth to adopt similar behaviour in their lives. | Qualitative study | -This study’s findings revealed that the portrayal of deviant behaviour in some television programmes results in the following forms of deviant behaviour among young people: premarital sex, the perception of women as sex objects, the use of profane language, the abuse of drugs and alcohol, involvement in gangster activities, and sexual confusion. -The study recommended that parents should monitor and regulate what their children watch on the television. |

| 23. Karam et al. The Integration of Family and Group Therapy as an Alternative to Juvenile Incarceration: A Quasi-Experimental Evaluation Using Parenting with Love and Limits. Family Process 2015; 56 (2): 331-347. (Research Article) | Family-based, USA. | -To evaluate the effectiveness of Parenting with Love and Limits (PLL), an integrative group and family therapy approach. | Quasi-experimental study | -This study contributes to the literature by suggesting that intensive community-based combined family and group treatment effectively curbs recidivism among high-risk juveniles. |

| 24. Nowakowski E, Mattern K. An Exploratory Study of the Characteristics that Prevent Youth from Completing a Family Violence Diversion Program. J of Fam Violence 2014; 29(1): 143-149. (Research Article) | Family-based, USA | -To explore the characteristics of youth who perpetrate violence against a family member. | Qualitative study | -Findings indicated that delinquency characteristics, explicitly having a prior violent arrest and skipping school, carry significance in preventing youth from completing the Family Violence Intervention Program. -These findings support the current literature and address the need for a more tailored approach for treating and retaining youth in a family violence intervention program. |

| 25. Murray J, Farrington. Risk factors for Conduct Disorder and delinquency: Key findings from longitudinal studies. Can J Psychiatry 2010; 55 (10): 633-642. (Research Article) | Family-based, UK. | -To review the most critical individual, family, and social risk factors for conduct disorder and delinquency on young people aged between 10 and 17 years. | Quantitative study | Offenders differ significantly from nonoffenders in many respects, including thoughtlessness, low IQ, low school achievement, poor parental supervision, punitive or erratic parental discipline, cold parental attitude, child physical abuse, parental conflict, disrupted families, antisocial parents, large family size, low family income, antisocial peers, high delinquency rate schools, and high crime neighbourhoods. |

| 26. Olufemi M, Ojo DA. Sociological Review of issues on Juvenile Delinquency. J of Int Soc Research 2012; 5 (21): 468 - 482. (Research Article) | Family, School, and Community-based, Nigeria |

-To examine issues on juvenile delinquency and the juvenile justice system. | Quantitative study. | It is recommended that the government assist families. Schools must incorporate teachings on juvenile delinquency in their curricula and provide good counselling departments and assistance to the less privileged students. -The communities should be encouraged to provide recreational facilities for the youths and encourage the youths to join social clubs and associations. The governments should train and equip the police, court, and reformatory homes to meet international standards to handle the juvenile justice system. |

| School-Based Studies | ||||

| Setting & Country | Study Objectives | Study Design | Outcomes/ Findings | |

| 27. Turkmen et al. Bullying among High School Students. J of Clin Medicine 2013; 8(2): 143-152. (Research Article) | School-based, Turkey. |

-To investigate the prevalence of bullying behaviour, its victims, the types of bullying, and places of bullying among the adolescents. | Quantitative study. | -A multidisciplinary approach involving affected children, their parents, school personnel, media, non-governmental organisations, and security units are required to achieve a practical approach to prevent violence targeting children in schools as victims and perpetrators. |

| 28. Sadinejad et al. Frequency of Aggressive Behaviours in a Nationally Representative Sample of Iranian Children and Adolescents: The CASPIAN-IV Study. Int J of Prev Medicine 2015; 6(6): 1-7. (Research Article) | School-based, Iran | -To explore the frequency of aggressive behaviours among a nationally representative sample of Iranian children and adolescents. | Quantitative study | Findings emphasise the importance of designing preventive interventions that target the students, especially in early adolescence, and increasing their awareness of aggressive behaviours. -Implications for future research and aggression prevention programming are recommended. |

| 29. Khuzwayo et al. Prevalence and correlates of violence among South African high school learners in uMgungundlovu District Municipality, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Sou Afri med Journal 2016; 106 (12): 1216-1221. (Research Article) | School-based, SA. | -To investigate the prevalence of violence and the demographic factors associated with such violence among South African (SA) high school learners in the uMgungundlovu District, KwaZulu-Natal, SA. | Quantitative study | -There were higher odds of male learners carrying weapons than female learners (OR 5.9, 95% CI 2.0 -15.0). -Violence among learners attending high schools in uMgungundlovu District is a significant problem and has consequences for their academic and social lives. -Urgent interventions are required to reduce the rates of violence among high school learners. |

| 30. Shahnila M, Rukhsana, K. Exploring Dimensions of Deviant Behaviour in Adolescent Boys. J of Beh Sciences. 2018; 28(1): 105-126. (Research Article) | School-based, Pakistan. | -To explore the dimensions of deviant behaviour in adolescent boys through an indigenous developed deviant behaviour scale, based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manuals. | Quantitative study | -The analysis identified three factors of deviant behaviour scale (α=.87), namely conduct disorder (CD; α=.96), intermittent explosive disorder (IED; α=.95), and oppositional defiant disorder (ODD; α=.93). -The results were compared and discussed by Pakistani culture and adolescents’ behavioural patterns. |

| 31. Zhang et al. Impact of media violence on aggressive attitude for adolescents. J of Health 2013; 5 (12): 2156-2161. (Research Article) | School-based, China | -To examine the impact of media violence on aggressive attitudes among Chinese adolescents. | Quantitative study. | -The findings imply that violent movies could effectively affect aggressive attitudes for adolescents in China. |

| 32. Magidi et al. High school learners’ experiences of gangsterism in Hanover Park. The Social Work Practitioner Researcher 2016; 28 (1): 69- 84. (Research Paper) | School-based, SA. | -To explore the experiences of non-gang school-going adolescents regarding gangs and gangsterism in Hanover Park in the Western Cape. | Qualitative study | -The results have shown that the presence of gangs affects the learners’ school attendance, restricts their mobility, increases bullying at school, and seriously disrupts family and community life. |

| 33. Estefanía E, Moreno D. Aggressive behaviours in adolescence as a predictor of personal, family, and school adjustment problems. Jour of Piscothema 2018; 30 (1): 63-73. (Research Article) | School-based, Spain |

-To determine the extent to which aggressive behaviours towards peers predict greater personal, school, and family maladjustment in adolescent aggressors of both sexes. | Quantitative study | -In the school setting, aggressive behaviours were related to low scores in academic engagement, friends in the classroom, perception of teacher support, and a positive attitude towards school. -At the family level, significant relationships were observed between aggressive behaviours and high scores in offensive communication and family conflict, low scores in open communication with parents, general expressiveness, and family cohesion. |

| 34. Tugli AK. Investigating Violence-related Behaviours among Learners in Rural Schools in South Africa. Int J of Edu Science. 2015; 10(1): 103-109. (Research Article) | School-based, SA. | -To investigate violence-related behaviours among rural learners in ten rural secondary schools within the Vhembe district of South Africa. | Quantitative study | -The school-based management and governing bodies must be adequately empowered to handle violent situations and security issues within and outside the perimeter of the learning environments. |

| 35. Silva S. Factors Associated with Violent Behaviour among Adolescents in North-eastern Brazil. Sci Wor Journal 2014; 20 (14): 1-7. (Research Article) | School-based, Brazil | -To identify prevalence and factors associated with violent behaviours among adolescents in Aracaju and the Metropolitan region. | Quantitative study. | -For both sexes, association between violent behaviours and cigarette smoking (OR = 3.77, CI 95% = 2.06 – 6.92 and OR = 1.99, CI 95% = 1.04 to 3.81, male and female, resp.) and alcohol consumption (OR=3.38,CI95%=2.22 to 5.16 and OR=1.83, CI95%=1.28 to2.63, male and female, resp.) was verified. -It was concluded that violent behaviours are associated with consuming alcoholic beverages and cigarettes among adolescents. |

| 36. Hanımoğlu E. Deviant Behaviour in School Setting. J of Educ and Train Studies 2018; 6(10): 133-141. (Research Article) | School-based, Turkey. |

-To examine causes and effects of deviant behaviour and identify main strategies to combat the issue. | Qualitative study | - Correction of deviant behaviours among teenagers should be carried out both by parents and professional psychologists, individual or group settings using various methods, e.g., destruction of a negative type of a character, adjustment of a motivational sphere and self-consciousness, stimulation of positive behaviour, etc. |

| 37. Hendricks EA. The Influence of Gangs on the Extent of School Violence in South Africa: A Case Study of Sarah Baartman District Municipality, Eastern Cape. J of con and soc Transformation 2018; 7(2): 75-93. (Research Article) | School-based, SA. | -To explore the influence of gangs on the extent of school violence in South Africa: A case study of Sarah Baartman District Municipality, Eastern Cape. | Qualitative study | -The findings revealed constantly escalating rates of sexual violence, physical violence, and vandalism on school property inflicted by gang members from both inside and outside the selected schools. -Mainly, the types of violence mentioned are caused due to excessive levels of substance abuse amongst these gang affiliates. Therefore, it is recommended that school security be increased and that the South African Police Services frequently patrol areas in which the respective schools are located. |

| 38. Mykota DB, Laye A. Violence Exposure and Victimization Among Rural Adolescents. Can J of Sch Psychology 2015; 30(2): 136-154. (Research Article) | School-based, Canada | -To examine the rates of violence exposure and the relative risk for multiple exposures among adolescent youth living in rural communities. | Quantitative study | -The results confirm that adolescents who live in rural areas were frequent victims of violence exposure and that males were more likely to be the victims than females. Moreover, the relative risk for multiple exposures either indirectly, directly, or in combination reveals that risk amplifies in all instances. |

| 39. Chen et al. Community Violence Exposure and Adolescent Delinquency: Examining a Spectrum of Promotive Factors. J of Youth & Society 2016; 48 (1): 33-57. (Research Article) | School-based, USA. | -To examine whether promotive factors (future expectations, family warmth, school attachment, and neighbourhood cohesion) moderated relationships between community violence exposure and youth delinquency. | Quantitative study | -Results indicate that while promotive factors from family, school, and neighbourhood domains are related to lower delinquency rates, only future expectations served as a protective factor that specifically buffered youth from the risk effects of community violence exposure. |

| 40. Buckley L, Chapman RL. Resiliency in Adolescence: Cumulative Risk and Promotive Factors Explain Violence and Transportation Risk Behaviours. J of Yout & Society 2020; 52(3): 311-331. (Research Article) | School based, Australia | -To identify associations among specific injury-risk behaviours with experience of higher cumulative risk factors and lower cumulative promotive factors (testing the compensatory model of resiliency). | Randomised control trial | -Findings showed the presence of risk factors increased the odds of engagement in unintentional and intentional injury-risk behaviour, and the presence of promotive factors decreased the odds, supporting a compensatory model of resiliency. -An interaction term of cumulative risk by promotive factors was a significant predictor in logistic regression analyses, suggesting that a protective-factor resiliency model also applies. |

| 41. Bushman et al. Youth Violence: What We Know and What We Need to Know. American Psychological Association 2016; 71(1):17–39. (Research Paper) | School-based, USA. | -The differences between violence in the context of rare rampage school shootings and much more common urban street violence. | Quantitative study | -Acts of violence are influenced by multiple factors, often acting together. We summarise evidence on some significant risk factors and protective factors for youth violence, highlighting individual and contextual factors, which often interact. |

| 42. Jackson et al. A systematic review of interventions to prevent substance use and risky sexual behaviour in young people. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health 2011; 65(1): 733-747. (Research Article) | School-based, UK. | -To identify and assess the effectiveness of experimental studies of interventions that report on multiple risk behaviour outcomes in young people. | Quantitative study. | There is some, albeit limited, evidence that programmes to reduce multiple risk behaviours in school children can be effective. The most promising programmes are those that address multiple domains of influence on risk behaviour. -Intervening in the mid-childhood school years may impact risky behaviour later, but further research is needed to determine the effectiveness of this approach. |

| 43. Gulpinar A, Savci B. Tendency to Violence in Adolescents and the Affecting Factors. Int Jour of Car Sciences 2018; 11(1): 262-266. (Research Article) | School-based, Turkey | -To identify the tendency to violence and the factors affecting 9th and 10th-grade adolescents in a city located in the Eastern part of Turkey. | Quantitative study. | It is recommended that one avoid demonstrating oppressive and authoritative attitudes towards adolescents; parents/teachers should avoid committing violence and demonstrate attitudes that help adolescents express themselves comfortably. -Besides, the tendency to commit violence could be decreased through education programs that help adolescents learn effective problem-solving skills without resorting to violence |

| 44. Yang et al. Physical Fighting and Associated Factors among Adolescents Aged 13–15 Years in Six Western Pacific Countries. Int Jour of Env Res and Publ Health 2017; 14 (11): 1-5. (Research Article) | School-based, China |

-To examine the prevalence of adolescent physical fighting in selected low- and middle-income countries and its relations with potential risk factors | Quantitative study | -The high prevalence of physical fighting and the associations with risky behaviours emphasise the need for comprehensive prevention programs to reduce youth violence and associated risk behaviours |

| Community-Based Studies | ||||

| 45. Jomon et al. Management of at-risk behaviour of adolescents in India: Revisited. International Journal of Management and Sciences Research Review. 2015; 1(16): 1-6. (Research Article) | Community-based, India | -To review the various efforts to understand the prevalence of risky behaviour among Indian adolescents and evaluate the socioeconomic and emotional factors potentially influencing these behaviours. | Quantitative study | -The development of effective prevention and intervention strategies for health risk behaviours should include theory-driven models and hypotheses and the identification and evaluation of mediators and moderators involved in the behaviour change process. -This study attempts to pool together the various efforts in India in understanding health risk behaviours and behaviour change by resorting to secondary sources of information. |

| 46. Van Biljon et al. The influence of a Diversion Programme on the Psycho-social functioning of youth in conflict with the law in the North-West Province. Acta J of Criminology 2011; 24(2): 75-93. (Research Article) | Community-based, SA. | -To review the influence of diversions programmes among the youth. | Quantitative study | The research found an improvement within the psycho-social functioning of those who completed the diversion programme. |

| 47. Barnert et al. Incarcerated Youths’ Perspectives on Protective Factors and Risk Factors for Juvenile Offending: A Qualitative Analysis. Am J of Pub Health 2015; 105(7): 1365-1371. (Research Article) | Community-based, Los Angeles. | -To understand incarcerated youths’ perspectives on the role of protective factors and risk factors for juvenile offending. | Qualitative study | -The adolescent participants described their homes, schools, and neighbourhoods as chaotic and unsafe. -They expressed a need for love and attention, discipline and control, and role models and perspective. -Youths perceived that when home or school failed to meet these needs, they spent more time on the streets, leading to incarceration. |

| 48. Abinader et al. Trends and correlates of youth violence-prevention program participation. A J of Prev Medicines 2019; 56(5): 680-688. (Research Article) | Community-based, USA. | -To address the elevated rates of youth fighting and violence. | Quantitative study. | -Youth participation in violence-prevention programs decreased significantly from 16.7% in 2002 to 11.7% in 2016, a 29% relative decrease in participation. -A significant declining trend in participation over time was found across all sociodemographic subgroups examined and among youth reporting the use of violence and no use of violence in the past year. -Participation among black/African American youth was significantly greater than Hispanic youth, who, in turn, had significantly higher participation rates than white youth. |

| 49. Ukoha E. Media Violence and Violent Behaviour of Nigerian Youth: Intervention Strategies. Nigerian Educational Research and Development Council 2013; 21(3): 230-237. (Research Paper) | Community-based, Nigeria. |

-To review the result of research on the effects of media violence on youths and try to relate these to the increased exhibition violence among Nigerian youths. | Quantitative study. | -The paper recommends, among other things, that the mass media should be censored more seriously. -Age limits should be indicated on media programmes sold in the market. Parents, teachers, caregivers, and even youths should be educated on the harm of consuming large doses of violent media content. -Research should be done to investigate the relationship between media violence and the violent behaviour of Nigerian youths. |

| 50. Atienzo et al. Interventions to prevent youth violence in Latin America: A systematic review. Int J of Publ Health 2017; 62(2): 15–29. (Research Article) | Community-based, Latin America. | -To summarise evidence on the effectiveness of interventions to prevent youth violence in Latin America. | Quantitative study. | -Most of the interventions had some promising results, including the reduction of homicides within communities. -Community-based programmes were the most consistent regarding effectiveness to prevent violence. |

| 51. Brendon Duran Faroa Exploring experiences and self-explanations of antisocial offending behaviours of a group of South African emerging adults.2018; University of Western Cape, South Africa. Master of Psychology. (Unpublished Thesis) | Community-based, SA. | -To explore experiences of a group of South African emerging adults who have engaged in antisocial offending behaviours. | Qualitative study | The findings indicated that participants invoked multiple causes and explanations and highlighted several factors that motivated their engagement in antisocial offending behaviours. -Moreover, participants’ explanations overwhelmingly attributed their antisocial offending behaviours to external factors in the home and social spaces. |

| 52. Mudau et al. Investigation of the Socio-Economic Factors that Influences Deviant Behaviours Among the Youth: A Case Study of Madonsi Village, South Africa. J of Gen & Behaviours. 2019; 17(1): 12630-12648. (Research Article) | Community-based, SA. | -To reveal socio-economic factors that contribute to deviant behaviours of youth and identify mechanisms to eradicate them. | Qualitative study | The study findings revealed that socioeconomic factors such as poverty, peer pressure, lack of sporting activities, and dysfunctional family negatively impact their behaviour. - It results in a situation in which they behave in the following way; abuse drugs, get involved in premarital sex, and abuse alcohol. |

| 53. Waimaru MW. Perceived factors influencing deviant behaviour among the youth in the Njathaini community. 2013; Nairobi, Kenya. Kenyatta University Master of Science in community Resources management. (Unpublished Thesis) | Community-based, Kenya. | To determine the factors contributing to deviant behaviours among the youth aged between 15-35 years in Njathaini semi- slum. | Quantitative study | The study concludes a relationship between socio-psychological factors and deviant behaviour among the youths in the study area. In other words, there is a relationship between deviant behaviour and unemployment, poverty, lack of skills, peer influence, and family influence. |

| 54. Azmawati et al. Risk-taking behaviours among urban and rural adolescents in two selected districts in Malaysia. J of South Afric fam practice. 2015; 1(1): 1-6. (Research Article) | Community-based, Malaysia | -To compare the prevalence of risk-taking behaviour and its associated factors among urban and rural adolescents. | Quantitative study | -Parental background factors such as parents' education level, marital status, health status, and income were unrelated to risk-taking behaviour among adolescents. -The multiple logistic regression tests showed that being a male (AOR = 4.55, 95% CI = 228–9.07), inadequate number of bedrooms (AOR = 11.54, 95% CI = 1.48–8975), and presence of family conflict (AOR = 3.64, 95% CI = 1.49–8.89) were the predictors among adolescents for risk-taking behaviour in rural areas. |

| 55. Barnie et al. Understanding Youth Violence in Kumasi: Does Community Socialization Matter? A Cross-Sectional Study. J of Urb studies 2017; 20 (17): 1-10. (Research Article) | Community-based, Ghana. | -To assess the causes and consequences of youth violence in the Kumasi Metropolis. | Quantitative study | -Principally, the categories of youth violence were manifested in noise-making, rape, murder, stealing, drug addiction, obscene gestures, robbery, sexual abuse, and embarrassment. -Peer pressure and street survival coping approaches emerged as the pivotal factors that induced youth violence. |

| 56. Khoury-Kassabri M, Schneider H. The Relationship Between Israeli Youth Participation in Physical Activity Programs and Antisocial behaviour. Chil and Adol Soc work Journal 2018; 35(1): 357–365. (Research Article) | Community-based, Israel. |

-To explore whether youth participation in sport and physical activity programs reduces their involvement in delinquent behaviours. | Quantitative study | -The findings highlight the importance of including sports programs in the interventions provided for at-risk youth and call for further investigation of the factors that may increase the benefits provided by participation in physical activity programs. |

| 57. Boxer P. Negative Peer Involvement in Multisystemic Therapy for the Treatment of Youth Problem Behaviours: Exploring Outcome and Process Variables in “Real-World” Practice. J of Clin Chil & Adol Psychology 2011; 40(6): 848–854. (Research Article) | Community-based, USA. | -The effects of negative peer involvement on case closure status and treatment characteristics in a large sample of adolescents enrolled in Multisystemic Therapy services. | Quantitative study | -Findings suggest that negative peer involvement is significantly related to treatment failure, mainly when negative peer involvement is comprised of gang affiliation. |

| 58. David-Ferdon et.al. A Comprehensive Technical Package for the Prevention of Youth Violence and Associated Risk Behaviours. 2016; Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. (Research Paper) | Community-based, USA. | -To increase public health leadership to prevent youth violence and promote the widespread use of youth violence prevention strategies based on the best available evidence | Quantitative study | -Findings suggest that mentoring and after-school approaches can benefit youth in several ways, including reducing their risk for involvement in crime and violence. However, the evidence of effectiveness varies by model and program. |

| 59. Mrug S, Windle M. Prospective effects of violence exposure across multiple contexts on early adolescents’ internalising and externalising problems. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 2010; 51(2): 953–961. (Research Article) | Community-based, USA. | -To address the gap by examining independent and interactive effects of witnessing violence and victimisation in the community, home, and school on subsequent internalising and externalising problems in early adolescence. | Quantitative study | -Violence exposure at home and school had the most potent independent effects on internalising and externalising outcomes. -Witnessing community violence attenuated the effects of witnessing home violence on anxiety and externalising problems, perhaps due to desensitisation or different norms or expectations regarding violence. |

| 60. De Ramos et al. An Assessment on the factors that influence the commission of crimes among selected male children in conflict with the law. J of Art and Scie Psych Research 2015; 2 (2): 149-166. (Research Article) | Community-based, Philippines. | -To assess the factors instigating the children in conflict with the law to commit such an act. | Quantitative study | -The results show that all the factors except external environment influence, which resulted in being not influential at all, are slightly influential in the committing of the crime. |

| 61. Khurana et al. Media violence exposure and aggression in adolescents: A risk and resilience perspective. Journal of Aggressive behaviour 2019; 45 (1): 70-81. (Research Article) | Community-based, Philadelphia | -To examine Black and White differences in media exposure and its effects on risk behaviours. | Quantitative study | -Targeted preventive interventions that reduce family conflict, promote parental monitoring, and reduce exposure to violent media may be effective in reducing aggressive tendencies and related adverse outcomes. |

| Amstar Questions | Answers | Justification |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Was ‘apriori' design provided? The research question and inclusion criteria should be established before conducting the review. |

Yes | Prior to conducting the literature review, a review protocol was developed. |

| 2. Was there duplicate study selection and data extraction? There should be at least two independent data extractors, and a consensus procedure for disagreements should be in place. |

Yes | The researcher and her two supervisors reviewed the articles and reports, and a straightforward procedure was followed to reach a consensus. |

| 3. Was a comprehensive literature search performed? At least two electronic sources should be searched. The report must include years and databases used (e.g., Central, EMBASE, and MEDLINE). Keywords and/or MESH terms must be stated, and the search strategy should be provided where feasible. All searches should be supplemented by consulting current contents, reviews, textbooks, specialised registers, or experts in the field of study and reviewing the references in the studies found. |

Yes | The review focused on quantitative and qualitative studies and reports obtained from GOOGLE SCHOLAR, SABINET, SAGE, EBSCO, and SCIENCE DIRECT. Keywords and search strategy were also taken into consideration. |

| 4. Was the status of publication (i.e., grey literature) used as an inclusion criterion? The authors should state that they searched for reports regardless of their publication type. The authors should state whether they excluded any reports (from the systematic review) based on their publication status, language, etc. |

Yes | The inclusion and exclusion criteria are fully described, and only studies written in English were included in this study. |

| 5. Was a list of studies (included and excluded) provided? A list of included and excluded studies should be provided. |

No | The list is only provided for included studies but can also be available for excluded studies. |

| 6. Were the characteristics of the included studies provided? In an aggregated form such as a table, data from the original studies should be provided on the participants, interventions, and outcomes. The ranges of characteristics in all the studies analysed, e.g., age, race, sex, relevant socioeconomic data, disease |

Yes | These were summarised as (Tables 1-3) that summarised the literature contributions according to three of Rodger’s characteristics: antecedents, attributes, and consequences. |

| 7. Was the scientific quality of the included studies assessed and documented? 'A priori' assessment methods should be provided. For example, effectiveness studies, if the author(s) chose to include only randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies, or allocation concealment as inclusion criteria); for other types of studies, alternative items will be relevant. |

Yes | These were assessed using the 14-point quality assessment tool and Rodger’s Evolutionary Conceptual Framework. |

| 8. Was the scientific quality of the included studies used appropriately in formulating conclusions? The methodological rigour and scientific quality results should be considered in the analysis and the conclusions of the review and explicitly stated in formulating recommendations. |

Yes | The included studies were guided and met Rodger’s Evolutionary conceptual analysis framework requirements. |

| 9. Were the methods used to combine the findings of studies appropriate? For the pooled results, a test should be done to ensure the studies were combinable, to assess their homogeneity (i.e., Chi-squared test for homogeneity, I2). If heterogeneity exists, a random-effects model should be used and/or the clinical appropriateness of combining should be considered (i.e., is it sensible to combine?). |

N/A | The review had a guiding conceptual framework; therefore, the combination of articles was guided by this framework. |

| 10. Was the likelihood of publication bias assessed? An assessment of publication bias should include a combination of graphical aids (e.g., funnel plot, other available tests) and/or statistical tests (e.g., Egger regression test). |

N/A | Rodger’s Evolutionary Concept Analysis framework guided the review. However, limitations of this systematic review are presented. |

| 11. Was the conflict of interest stated? Potential sources of support should be acknowledged in both the systematic review and the included studies. |

Yes | The author declared that she did not have any conflict of interest. |

3.2.2. Exclusion Criteria

In this study, the exclusion criteria are:

- Studies that focus on people older than the age of 35 years.

- Publications not written in English.

- Studies published outside of the given time period.

- Studies that focus on the factors contributing to violent behaviours and rehabilitation programmes in other age groups.

3.2.3. Search Strategy

To achieve this, the researchers searched a variety of research databases on empirical and grey research literature. The review has focused on quantitative and qualitative studies and reports obtained from GOOGLE SCHOLAR, SABINET, SAGE, EBSCO-HOST, and SCIENCE DIRECT. Keywords and search strategy were also taken into consideration. Key concepts and search terms were developed to capture literature related to the rehabilitation of violent behaviours amongst the youth. The search strategy was used in collaboration with a health sciences librarian. An example of search terms used in Sabinet is: “Violent behaviours *or Deviant behaviours* AND therapy * or programmes* or interventions*” AND violence prevention and young people or adolescents.” Furthermore, additional references were found by systematically examining the reference lists of relevant papers and reviews.

3.2.4. Methods of Review

In this study, the titles and abstracts were reviewed to identify relevant articles and reports and then included. Full texts of these articles and reports that met the inclusion criteria were also reviewed, and their findings were discussed.

3.2.5. Data Extraction and Synthesis

A data collection form was developed, guided by Rodger’s Evolutionary Conceptual Analysis Framework, to collect data on antecedents, attributes, and consequences of Rehabilitation strategies on violent youth behaviours from the articles and reports that met the inclusion criteria. The findings from the reports and articles were then coded and thematically analysed to identify and explain the antecedents, attributes, and consequences of rehabilitation strategies on youths’ violent behaviours.

4. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

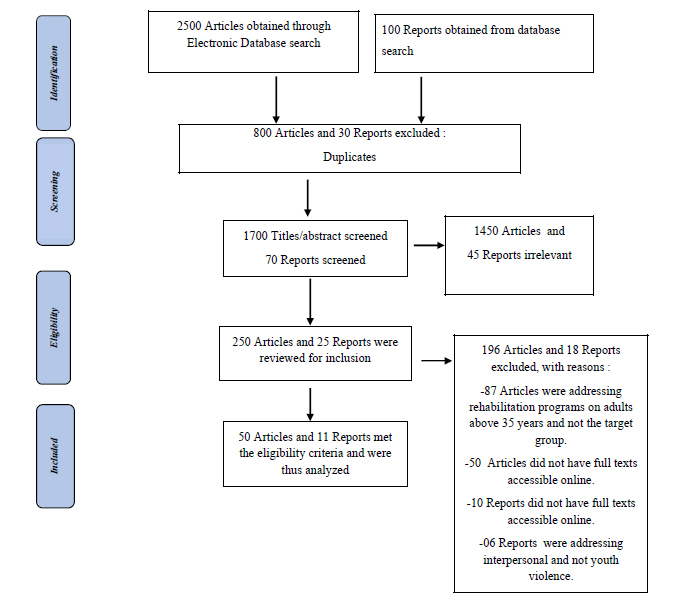

There were 2500 articles and 100 reports that were obtained through an electronic database search. After the screening of duplicates, 1700 articles and 70 reports were reviewed by titles and abstracts. Of these articles and reports reviewed, 1450 articles and 45 reports were excluded as they were irrelevant to the study.

|

Fig. (1). Adapted flow chart of the literature search for the included and excluded studies (Wu & Lin, Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group (2009)). |

The 250 articles and 25 reports were then reviewed to determine if they met the inclusion criteria. After reviewing articles and reports, it was found that 50 articles and 11 reports met the inclusion criteria and were then analysed. The results are summarised on the PRISMA flow chart diagram, as displayed in Fig. (1).

4.1. Quality Assessment

In this study, a quality evaluation tool was used to assess the quality of selected studies in line with Rodger’s Evolutionary Concept Analysis Framework [10]. The included reviews’ methodological quality was assessed using the AMSTAR quality assessment tool (a measurement tool to assess systematic reviews). The reports and articles were assessed for clarity in presenting antecedents, attributes, and consequences of rehabilitation strategies on violent youth behaviours.

The AMSTAR tool was developed to check the quality of a systematic review and determine whether the most important elements are considered, as shown in Table 2. A Prisma checklist was also completed to ensure that the study fulfilled the expectation of the review articles.

4.2. Timeline

The literature search was performed from January 2020 to May 2020. Quality appraisal then followed in June, and data extraction, synthesis, and writing up were done between March and July 2020.

4.3. Outcome of Quality Assessment Tools

The articles selected in this systematic review were subject to a 14-point quality assessment tool and met the minimum standard required. The reports and articles were assessed for clarity in presenting antecedents, attributes, and consequences of rehabilitation strategies on violent youth behaviours.

The AMSTAR tool was developed to check a systematic review’s quality and determine whether the most critical elements are reported. These findings are presented in Table 2.

5. DEFINITION OF VIOLENT BEHAVIOURS

Violent behaviour is defined as conduct un-approved by society, which means that such behaviours vary from one society to another. In addition, in most countries, young people constitute both the majority of perpetrators and victims of violence and offence, and violence prevention measures with a strong focus on youth have a great potential to reduce violence and offence rates across society. The prevention efforts can reduce youth’s susceptibility to violence and crime by addressing the root causes of youth violence and strengthening young people’s resilience to risk factors [11-13].

5.1. Antecedents, Attributes, and Consequences of Rehabilitation strategies with violent youth behaviour.

5.1.1. Antecedents

In this study, the antecedents that influence violent youth behaviours reported in the literature were: Family structure, increased bullying resulting from the gang, and gender and environmental factors. Literature sources reporting these antecedents are summarised in Table 3.

5.1.1.1. Family Structure

Family is regarded as the first institution in which an individual interacts. Most studies have found that children from broken families are more likely to deviate than intact families [14]. Violent behaviour is a likely outcome, especially when children continuously witness dysfunctional behaviour displayed by authority figures that they trust, particularly if it is not sanctioned or punished. Moreover, parenting serves the role of a root mechanism through which children learn appropriate and inappropriate behaviour as they come to understand the roles and norms of the communities [14].

Mambende et al. [15] add that family-related risk factors include poor parenting skills, family disruption, minimal attachment to parents, and parents or relatives with criminality or substance abuse problems. These findings are supported by World Youth Report, which claimed that dysfunctional family settings characterised by conflict, inadequate parental control, and weak internal linkages are closely associated with juvenile delinquency.

5.1.1.2. Increased Bullying as a Result of Gangs

Magidi et al. [16] highlight that gang presence increases the culture of violence and bullying and increases the victimisation and bullying of both learners and teachers. A report published in the New York Times supports the above statement by reporting that 4.5% to 7.5% of the students in the USA carry some weapon with them to school. The authors also confirm that using a variety of weaponry by gangsters in schools, such as guns, knives, bottles, and sharpened pencils, is used to threaten and control other learners [17].

The same authors further highlight that the availability of weapons in schools has a psychological effect on non-gang learners. As a result, they are conditioned to believe that violence is the way to resolve specific problems. In addition, these authors believe that the behaviour among gangs, such as responding to insults and offences through violence and weapons, leads to the normalisation and justification of carrying weapons by everyone, including non-gang-affiliated learners [17].

5.1.1.3. The influence of Gender and Environmental Factors

One study reported a higher frequency of physical fighting among boys than girls. This finding is in line with other studies that argued that boys’ engagement in occasional fighting might be because of the potential influence of gender norms on the involvement in physical fighting. However, the same study demonstrates that girls are more likely to fight in intimate relationships, whereas boys fight with strangers [18-21]. It is revealed that community disorganisation, economic inequality and relative deprivation, high unemployment rates, and the availability of alcohol and drugs in the neighbourhood may contribute to violent behaviour. This implies that the environment in which youth are reared can influence tendencies towards delinquency [22].

| Key Antecedents Factors | Supporting literature |

|---|---|

| Family structure | [14, 15] |

| Increased bullying as a result of gangs | [16, 17] |

| The influence of gender and environmental factors | [18-22] |

5.1.2. Attributes

Violent behaviour attributes obtained from the literature are motivation, contextual differences, transformation, opportunity, and ineffectiveness. Literature sources reporting these attributes are summarised in Table 3.

5.1.2.1. Motivation

Literature reports that youth with multiple characteristics are at greater risk for termination of programmes. The number one reason for this termination is non-participation in intervention services; thus, more incredible support is needed to ensure retention and successful programmes [23]. In Rehabilitation Strategies (RSs), the treatment options seem limited for violent delinquent youth, and a need exists for more research to create models of practice for working with such youth.

5.1.2.2. Contextual Differences

While the barriers and enablers to youth violent rehabilitation programmes were applicable in different societies, the literature reveals several contextual differences, including age, gender, culture, mode of delivery, financial resources, and location of services.

These contextual elements are important factors to consider when designing rehabilitation interventions in different countries [23]. Collective intervention is needed to address different societal values and differences.

5.1.2.3. Transformation

Literature also highlights that if parents can participate meaningfully in rehabilitation programs to transform their children’s offending behaviour, they can learn about the contribution of specific home and family circumstances to their children, particularly in criminal activities [14].

However, it is reported that in the absence of parents/guardians to constrain this behavioural expression carefully, adolescents’ deviant behaviour may progress to delinquency. Once parents are alerted about their children’s behaviours by the criminal justice authorities, they take things personally instead of finding good ways of resolving conflict [14].

5.1.2.4. Opportunity

Due to high-risk behaviour in youth correctional centres, such as gang activities, inmates’ affiliates to various gangs occurs to protect themselves against possible violations from other inmates. As a result, some young people continue to display antisocial behaviour even after being exposed to diversion programmes due to a shortage of staff members to monitor them in the institutions [24]. Follow-up services and tracking the young people during their reintegration into their communities would discourage young individuals from sliding back into anti-social behaviour.

5.1.2.5. Ineffectiveness

Due to different perceptions among the parents/guardians of the youth and the youth regarding the refusal of participating in family group conferencing, the programme becomes ineffective. In some cases, the parents did not seem to be ready to forgive the young offenders. Some young offenders attend rehabilitations programmes only to avoid prosecution, and such individuals have a negative attitude and are challenging to deal with [24]. Literature also highlights that it is problematic and challenging to work and achieve the intended goals with young offenders who can avoid prosecutions. As a result of these negative attitudes, the same young offenders will likely find themselves back in the centres in no time [24].

5.1.3. Consequences

This study reports the consequences of these antecedents and attributes in Table 3: Incompletion of youth intervention programs and low-income family intervention programmes.

5.1.3.1. Incompletion of Youth Rehabilitation Programmes

Literature reports that youth with more delinquency characteristics were less likely to complete the diversion program. It highlighted a need for a thorough assessment of family distinguishing socio-demographic and delinquency characteristics that contribute to violence and individualising treatment [25]. Diversion refers to the referral of youth offenders away from the criminal courts when appropriate, and it serves various purposes. These include encouraging the youth to take responsibility for their actions, allowing victims to express their views on the harm that the offender caused, and advocating reconciliation between the offender and the victim [26].

Studies highlight that youth with multiple delinquency characteristics are at the most significant risk for programme termination. There is a need for them to be connected to services that meet their individual needs for diversion to be successful. Terminated youth perpetrators have a history of more violent arrests, use more substances, and are more likely to skip schools than those who complete the programmes [22].

The number one reason for termination from the programme was non-participation in the intervention services. Thus, greater support is needed for those youth with multiple delinquency characteristics to ensure retention and successful completion of the programme. Treatment options seem limited for violent delinquent youth, and a need exists for more research to create models of practice for working with such youth. Furthermore, curricula and intervention components should be established based on data collected from research that examines programme participants [22].

5.1.3.2. Poor Family Involvement in Youth Programmes

According to certain studies [27, 28], some types of parenting increase the likelihood of a child committing offences. Poor parental supervision is usually the strongest and most replicable predictor of offending based on the child-rearing methods.

These authors further revealed that children who are not provided with support and authoritarian parents who tend to emphasise rules and harsh consequences also increase the probability of children returning to violent activities. It is paramount during the rehabilitation process that parents or guardians be involved in supporting their children at all costs. It is also essential for parents or family members to foster family cohesion, unity, and good parenting styles to combat youth violence [28].

|

Fig. (2). Conceptual Framework of Rehabilitation strategies and violent youth behaviours as informed by findings. |

6. DISCUSSION

6.1. Conceptual Framework

The conceptual framework based on the findings of this study is presented in Fig. (2) as a summarised model. In addition, the model also includes the proposed strategies found in the literature that are aimed at improving violent youth behaviours.

6.2. Proposed Strategies to Prevent Violent Youth Behaviours

6.2.1. Behaviour Modification in Schools

According to David-Ferdon et al. [1], school violence is preventable. Learners’ academic success and social well-being are a product of safe and supportive school and home environments, including healthy social relations. Since the children spend approximately half of their day at school, the schools also serve as the most crucial socialising environment after the home. Violent behaviour is associated with alcohol and cigarette consumption. Intervention in the school environment should be implemented, either in the continued preparation of teachers or in the development of curricula where these issues comprise the day-to-day lives of students. Furthermore, it was stated in the same literature that the school-based behaviour modification and intervention programmes designed with inputs from all stakeholders such as community structures, parents, educators, learners, and union representatives should be introduced in all schools and at all phases [16, 29].

6.2.2. Reduction of Media Violence Exposure

Media violence exposure is associated with aggressive outcomes in youth and adolescents. The portrayals of violence on TV and movies are often unrealistic, associated with rewards and negative consequences, reinforcing observational learning and making youth more likely to engage in similar behaviour in real life [30]. Literature reports that using active mediation strategies such as discussion of media content to understand the values better can have a protective influence on aggression by contextualising what children watch.

Zhang et al. [21] highlight that with the rapid development of the film industry, various violent movies indicated that numerous adolescents got easy access to violent movies in their daily lives. Thus, they are prone to forming aggressive cognition, attitude, and violent behaviour based on their brain plasticity from a developmental perspective. The same study suggests that media violence exposure is a significant risk factor for aggression in adolescents and operates with other risk factors. Targeted preventive interventions that help reduce exposure to violent media content, strengthen self-regulation, and promote parental monitoring could reduce adolescents’ aggression and related adverse outcomes [21].

6.2.3. Family Planning and Adequate Socialisation

Family planning results in few children being born in families, and as a result, parents, single or married, can rear their children adequately to prevent the development of criminal personality [14]. Furthermore, family planning prevents the adherence to traditional customs encouraging most women and men to give birth with limited or few financial resources. The same author also suggests that policymakers should emphasise family planning, parenting programmes, and parental involvement in children’s activities combined. These strategies will prevent violence and contribute to the financial growth of families [14].

6.2.4. Strengthening Youth Rehabilitation Programmes

The literature argues that diversion involves the referral of the youth offenders away from the criminal courts when appropriate, and it serves various purposes. These further include encouraging the youth to take responsibility for their actions, allowing victims to express their views on the offenders’ causes, and advocating reconciliation between the offender and the victim [31]. Diversion programmes give young people a chance to avoid criminal records while at the same time teaching them to acknowledge responsibility for their actions. As a result of these programmes, the youth involved in criminal activities turn into advocates and role models of positive behaviour for other young people.