All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Examining Housing as a Determinant of Health: Closing the ‘Poverty Gap’ to Improve Outcomes for Women in Affordable Housing

Abstract

Background:

Access to housing is an important social determinant of health and has a positive influence on health outcomes. In one large municipal city in Western Canada, over 12,000 units of affordable housing are available to support low-income individuals.

Objectives:

However, little is known about resident experiences living in affordable housing, how affordable housing affects their movements through the housing continuum (i.e., from housing instability to stability), how affordable housing affects their lives and the lives of their families, and how gender factors into these questions.

Methods:

The current study, part of the larger quantitative project, involved a survey with 160 residents of affordable housing units in Calgary, Alberta, Canada.

Results:

The results show that few gender differences exist in demographic factors such as age, income, and ethnicity. However, important differences exist in the experiences of women versus men, including employment status, barriers to employment, parenting, trajectory of affordable housing residency, and reasons for accessing affordable housing in the first place.

Conclusion:

We argue that gendered supports to reduce barriers to sustainable employment must be embedded in affordable housing programs and coupled with low or no cost childcare and supports to heal from trauma in order to break cycles of dependency for women and their children. This research builds on the scant Canadian literature that examines characteristics and experiences in affordable housing using a gender-lens.

1. INTRODUCTION

Researchers argue that stable housing offered within a coordinated ‘system of care’ is the first and most important step to healthy families and healthy communities and that without housing, interventions to improve health outcomes, reduce poverty, improve access to education and employment are ineffective and often impossible [1]. In Canada, housing is considered “affordable” if it costs less than 30% of a household’s before-tax income. Affordable housing includes housing in private, public, and non-profit sectors in all forms (i.e., rental, ownership, co-operative, temporary, and permanent housing) [2]. As of 2018, over 1 in 10 renters (13.5%) or 628,700 Canadian households were living in affordable housing [3]. Other than temporary emergency benefits during the COVID-19 pandemic, there are no federal level housing subsidy policy/programs to support low-income people directly. Provinces and territories administer a large majority of the federal agreements with social housing providers, several of these operating agreements are set to expire in the next several years [4]. This creates some uncertainty for the future of these units and their tenants.

This study focuses on a large Western Canadian city, Calgary, Alberta. Seventy-five percent of Calgary households have insufficient income to buy a single-family house [5], and so access to affordable rental units is very important. Calgary’s market rental rates are among the highest in Canada and supply is limited, making rental units, particularly in the lower end of the spectrum, unaffordable and inaccessible for many. Currently, the income level required to afford the average rent for a two-bedroom apartment in Calgary (i.e., the rent is less than 30% of housing income), is $26.97 an hour or approximately $53,000.00 CAD annually. There are presently no neighbourhoods in the City of Calgary where someone working full time and earning a minimum wage could afford to rent a one-bedroom apartment [6].

There are approximately 43 agencies in the city of Calgary offering more than 12,000 units of affordable housing (AH). The largest provider has a waitlist of more than 4,000 individuals and families. The city estimates that 1 in 5 households are struggling to pay for shelter costs and that by 2025 there will be more than 100,000 households in housing need [7]. Many AH providers are only collecting data on the numbers of clients they house and turnover rates. Many are not collecting data on who they house, for how long, and most importantly, program, population or health outcomes.

Access to safe, stable and affordable housing is argued necessary for physical and social wellbeing. It is the place where children are raised and it creates ‘space’ for social and familiar networks and supports. It is important for living with dignity and helps shape identities and a sense of belonging [8]. However, literature on the impacts of living in AH is mixed. For example, some researchers have argued there is a ‘poverty trap’ meaning that living in AH creates dependency and significantly increases the probability of long-term dependency on government support for housing and social assistance or welfare and that children and youth who grow up in AH are at high risk for poverty and dependency in adulthood [9, 10]. Researchers have also argued that children in AH have poor health and education outcomes compared with peer groups in market housing [11].

Gender impacts housing access and experiences in affordable housing. Lone-parents in Canada are largely female-headed households and the need for housing is elevated for this group [12]. However, women’s perspectives have been largely left out of the affordable housing literature [13, 14]. This is problematic since we know that there are important inequities that disproportionately affect women. For instance, female single-parent families are more likely to spend a greater portion of their incomes on shelter than their male or dual parent familial counterparts [15]. Additionally, Canadian women have a higher rate of poverty than Canadian men overall in the age group 11-44 years of age and again after 65 years of age [16]. Women are typically the primary caregivers of their children and inaccessible or unaffordable childcare is a barrier that keeps women out of the workforce and out of education and training opportunities [17]. Women in poverty are at high risk of homelessness and women in homelessness report high rates of trauma, mental health issues like depression and high rates of sexual exploitation, violence, and assault [18]. Many also report interactions with multiple and disjointed systems in their attempt to ‘deal with’ or get support for the complex and intersecting issues they face [19]. Women from equity seeking groups face additional barriers related to racism and discrimination [20, 21].

Housing for women, in particular, is important for independence and can determine the capacity and opportunities a woman may have to make decisions about her and her children’s future [22]. A critical review focused on North American studies that examined housing and social issues showed that few of the articles the authors found focused on the gendered nature of affordable or public housing [23]. The authors located one study which discovered that residing in public housing significantly worsened a mothers’ health status. In terms of housing studies that take a gender-lens, much of the literature focuses on homelessness, not affordable housing [24-28].

A survey completed for the Canadian Mortgage and Housing Corporation in 2019, found that access to housing, physical safety and housing discrimination could all be better addressed by thoroughly applying a gender-based approach [29]. This survey found that while the housing system is meeting many of the needs of women, there are additional needs related to domestic violence, homelessness, and the need for supportive services (generally provided through other policy sectors) such as mental health, disability, and childcare that are largely under addressed [30]. The authors of the CMHC survey study also reviewed 29 publications and found there were diverse approaches to addressing women’s housing needs and that women’s housing needs were unique but that more research is needed to determine the most effective and meaningful ways to implement change.

With affordable housing being a sizable and necessary component of a city’s housing milieu, and an important social determinant of health, there is a need for exploration into the experiences of people who live in these units. Affordable housing, while a crucial part of the housing fabric in Canada, is not experienced equitably for all social, cultural and economic groups. The number and scope of studies on women’s experiences in AH are disproportionate to the stated need in demographic survey data [31-33].

This small quantitative study aims to help address this gap by focusing on affordable housing locations in Calgary, Alberta, Canada and examining how gender influences experiences and outcomes for tenants in these residences. The current study aims to investigate the following inter-related research questions: What are the experiences of individuals living in affordable housing in Calgary and do these experiences differ by gender? How does gender affect trajectories through housing? Are there gender-specific issues that need to be considered to better support families living in affordable housing and/or to support a move to market housing?

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Design

The study was a descriptive-cross-sectional survey administered online or in-person with tenants living in affordable housing units. One hundred and sixty-five people participated.

2.2. Data Collection

Individuals were eligible to participate if they were over 18 years of age, had lived in an AH unit for the last 6 months, and could respond to the questions in English. Recruitment for the questionnaire was done through posters and property managers within two of the city’s largest AH providers. Participants volunteered to complete the questionnaires online or in-person. Researchers visited multiple housing sites to provide the opportunity for in-person recruitment, attending community or on-site events. An accurate response rate is difficult to calculate as the research team did not reach out to individuals through an established contact list, rather we sought out volunteer participants by circulating information about the study through property managers. Volunteer participants received a $20 gift card to thank them for their time. The questionnaires were designed in collaboration with a Community Advisory Committee and included items on demographic information, housing trajectories, experiences in affordable housing for the individual and their children, plans for the future, and also gave participants an opportunity to give feedback on their affordable housing experience. Participants were required to self-report their data. If literacy was an issue, a research assistant was available to support the participant in completing the survey.

2.3. Data Analysis

One incomplete (unfinished survey) was removed from the database. Variables were cleaned and coded based on self-reported information from the surveys using Stata 12. Quantitative variables were coded into meaningful categorical or binary variables, depending on sample size and participant response. Qualitative responses (e.g., how would you define success?) were themed and re-coded into numeric responses. Because of the small sample size, data analysis was mainly descriptive, reporting proportions and 95% confidence intervals. To determine differences between groups, we conducted chi-squared tests; we deemed statistically significant differences to be evident if the probability level was less than 0.05. Metrics of importance for the research questions included gender differences in education and employment, incidence of lone-parent families with children, experiences of domestic violence and length of stay in AH.

2.4. Ethical Considerations

This study was approved by the University of Calgary Conjoint Health Ethics Review Board (REB 17-0816). The participants were given a detailed explanation of the purpose of the study and provisions for privacy and confidentiality. All participants provided signed consent. Participants were informed that they could discontinue at any given stage during the survey if they felt uncomfortable without any consequences to their current or future service delivery options.

2.5. Community Advisory Committee

To ensure relevant questions were asked through the survey and to facilitate data collection, the research team collaborated with a group of subject matter experts, academics, and service providers. Collectively termed the Community Advisory Committee, this group included individuals from local and provincial housing providers, policymakers, and academics from several departments at the University of Calgary. This group helped to build the survey items, decide on appropriate wording and categorization, and to provide insight into the interpretation of results.

3. RESULTS

Overall, this study reports the results of a small quantitative questionnaire conducted with 160 individuals between 2017 and 2019 in Calgary, Alberta, Canada. Table 1 denotes the demographic characteristics of the study sample. Overall, women and men in our sample were similar in age, household income, income source, and ethnicity. However, women were significantly more likely to have lower education and single compared to men.

| Female | Male | Significance Level | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Number of Participants | 135 (84.4%) | 25 (15.6%) | - | |

| Age | 18-34 years | 46 (34.6%, 26.4-42.8%) | 5 (20.8%, 4.1-37.6%) | p=0.363 |

| 35-49 years | 60 (45.1%, 36.6-53.7%) | 12 (50.0%, 29.4-70.6%) | ||

| 50+ years | 27 (20.3%, 13.4-27.2%) | 7 (29.2%, 10.4-47.9%) | ||

| Education | Some Secondary School | 12 (32.0%, 23.6-40.3%) | 3 (13.6%, 1.2-28.4%) | p=0.019 |

| High School Graduate | 30 (24.6%, 16.9-32.3%) | 7 (31.8%, 11.7-51.9%) | ||

| Some College/ University | 27 (22.1%, 14.7-29.6%) | 3 (13.6%, 1.2-28.4%) | ||

| College or University Graduate | 36 (18.9%, 11.8-25.9%) | 9 (22.7%, 4.7-40.8%) | ||

| Household Income | Less than $25,000 per year | 100 (76.9%, 69.6-84.3%) | 18 (78.3, 60.9-95.6%) | p=0.888 |

| More than $25,000 per year | 30 (23.1%, 15.7-30.4%) | 5 (21.7%, 4.4-39.1%) | ||

| Other (Pension, Child Tax Benefit) | 8 (6.8%, 2.2-11.5%) | 3 (12.5%, 1.1-26.1%) | ||

| Marital Status | Single, Divorced, or Widowed | 91 (71.1%, 63.1-79.0%) | 12 (50.0%, 29.4-70.6%) | p=0.042 |

| Married, Partnered, or Common-Law | 37 (28.9%, 21.0-36.9%) | 12 (50.0%, 29.4-70.6%) | ||

| Ethnicity | Caucasian | 51 (43.6%, 34.5-52.7%) | 13 (59.1%, 37.9-80.3%) | p=0.187 |

| African or African American | 24 (20.5%, 13.1-27.9%) | 6 (27.3%, 8.1-46.5% | ||

| Indigenous | 13 (11.1%, 5.3-16.9%) | 0 | ||

| Other | 29 (24.8%, 16.9-32.7%) | 3 (13.6%, 1.2-28.4%) | ||

Table 2 describes the financial and employment characteristics of the sample of tenants in affordable housing. Overall, there were no major differences by gender in household income. There were also no significant differences in income by household income and gender if the respondent was a single parent or not, nor if they had children or not. Source of income also did not vary by gender. Only 29.1% of women (95% CI: 20.7-37.4%) and 41.7% of men (95% CI: 21.3-62.0%) reported any employment. Approximately 20.5% of women and 25.0% of men were receiving Assured Income for the Severely Handicapped (AISH)1. As well, 43.6% of women and 20.8% of men were receiving financial support from Alberta Works Income Support2. Approximately one-third of the sample reported being unable to work. Of those respondents who reported being able to work, 39.5% of women and 25.0% of men were unemployed. Many reported barriers to employment; these did not have statistically significant differences by gender, except for childcare, which was reported as a barrier to employment by 25.2% of women and none of the men in our sample (p=0.005).

Family characteristics are described in Table 3. In terms of family, there were significant differences between men and women. Overall, 92.5% of the women (95%CI: 88.0-97.0%) and 56.0% (95%CI: 36.0-76.0%) of men had children (p<0.001). Approximately 74.1% of women and 44.0% of women had at least one child under the age of 18 years (p=0.003). As well, 44.4% of women who had children reported being single parent compared to only 4.0% of men (p<0.001). However, this analysis may be limited by small sample size.

| Female | Male | Significance | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Household Income | Less than $25,000 per year | 100 (76.9%, 69.6-84.3%) | 18 (78.3, 60.9-95.6%) | p=0.888 |

| More than $25,000 per year | 30 (23.1%, 15.7-30.4%) | 5 (21.7%, 4.4-39.1%) | ||

| Income Source | Assured Income for the Severely Handicapped (AISH) | 24 (20.5%, 13.1-27.9%) | 6 (25.0%, 7.1-42.9%) | p=0.202 |

| Alberta Works | 51 (43.6%, 34.5-52.7%) | 5 (20.8%, 4.1-37.6%) | ||

| Employment (full- or part-time) | 34 (29.1%, 20.7-37.4%) | 10 (41.7%, 21.3-62.0%) | ||

| Other (Pension, Child Tax Benefit) | 8 (6.8%, 2.2-11.5%) | 3 (12.5%, 1.1-26.1%) | ||

| Employed | Any employment | 30 (22.9%, 16.5-30.9%) | 9 (39.1%, 21.7-59.9%) | p=0.099 |

| Full-time employment | 8 (5.9%, 3.0-11.5%) | 4 (16.0%, 6.1-35.9%) | p=0.079 | |

| Part-time employment | 31 (23.0%, 16.6-30.9) | 7 (28.0%, 13.9-48.4%) | P=0.587 | |

| Ability to Work | Unable to work | 48 (37.2%, 29.3-45.9%) | 9 (37.5%, 20.7-58.0%) | p=0.252 |

| Able to work but unemployed | 51 (39.5%, 31.4-48.3%) | 6 (25.0%, 11.6-45.8%) | ||

| Able to work and employed | 30 (23.3%, 16.7-31.4%) | 9 (37.5%, 20.7-58.0%) | ||

| Barriers to Employment | Cannot find a job | 36 (26.7%, 19.8-34.8%) | 8 (32.0%, 16.8-52.3%) | p=0.583 |

| Cannot find childcare | 34 (25.2%, 18.5-33.2%) | 0 (N/A) | p=0.005 | |

| Ill or disabled | 34 (25.2%, 18.5-33.2%) | 3 (12.0%, 3.9-31.5%) | p=0.151 | |

| Language issues | 8 (5.9%, 3.0-11.5%) | 0 (N/A) | p=0.212 | |

| Worried about making too much money (not qualifying for low-income housing) | 7 (5.2%, 2.5-10.5%) | 1 (4.0%, 0.6-23.8%) | p=0.803 | |

| Female (n=135) | Male (n=25) | Significance | |

| Has Children | 124 (92.5%, 88.0-97.0%) | 14 (56.0%, 36.0-76.0%) | p<0.001 |

| Single parent | 60 (44.4%, 36.0-52.9%) | 1 (4.0%, 0.0-11.9%) | p<0.001 |

| Has at least one child under 18 years | 100 (74.1%, 66.6-81.6%) | 11 (44.0%, 24.0-64.0%) | p=0.003 |

| Children (less than 18 years) are in your care | 98 (95.1%, 88.8-98.0%) | 10 (90.9%, 55.6-98.8%) | p=0.550 |

| Female | Male | Significance | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of Housing before Moving into Current AH Unit | Homeless | 38 (29.9%, 21.9-38.0%) | 6 (27.3%, 8.1-46.5%) | p=0.506 |

| Another AH Building | 14 (11.0%, 5.5-16.5%) | 5 (22.7%, 4.7-40.8%) | ||

| With Family | 33 (26.0%, 18.3-33.7%) | 5 (22.7%, 4.7-40.8%) | ||

| Renting or Owned Market Housing | 42 (33.1%, 24.8-41.4%) | 6 (27.3%, 8.1-46.5%) | ||

| Main Reason for Moving into Affordable Housing | Domestic Violence | 20 (14.8%, 9.7-21.9%) | 0 | p=0.040 |

| Lost Job | 17 (12.6%, 7.9-19.4%) | 4 (16.0%, 6.1-35.9%) | p=0.643 | |

| Could not afford market housing | 88 (65.2%, 56.7-72.8%) | 16 (64.0%, 43.8-80.2%) | p=0.909 | |

| Poor Health | 17 (12.6%, 7.9-19.4%) | 2 (8.0%, 2.0-27.2%) | p=0.514 | |

| Ever Experienced Homelessness | 42 (32.8%, 24.6-41.0%) | 8 (36.4%, 15.6-57.1%) | p=0.744 | |

| Has extended family who live in affordable housing | 26 (21.7%, 14.2-29.1%) | 1 (5.0%, 0.0-14.9%) | p=0.080 | |

| Lived in affordable housing as a child | 13 (10.9%, 5.2-16.6%) | 5 (23.8%, 5.0-42.6%) | p=0.104 | |

Table 4 describes the participants’ trajectories into housing by gender. Overall, there were no significant differences in the types of housing the participants lived in before entering into their current affordable housing unit (p=0.506). Approximately one-third of participants were experiencing homelessness before moving into their current housing, one-quarter were living with family and one-third were living in market housing. However, women were more likely to indicate that their main reason for moving into affordable housing was domestic violence (p=0.040).

3.1. Experiences in Housing

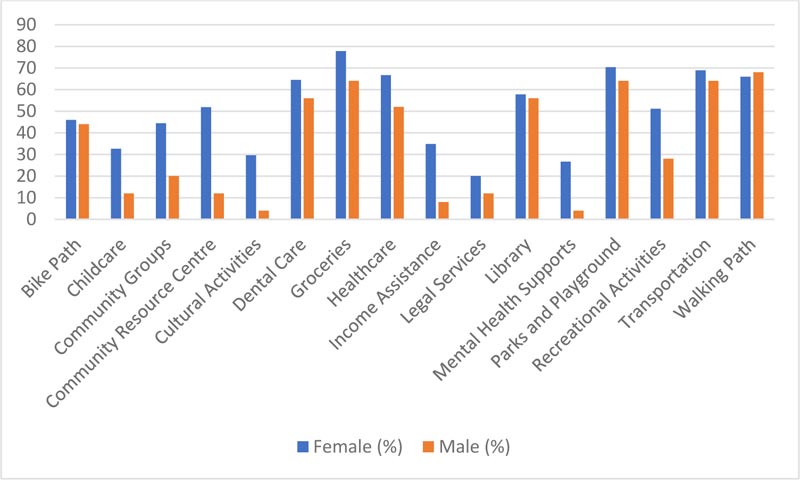

Overall, participants reported varying access to services within their neighbourhood (Fig. 1). Access to several services differed by gender, such as childcare (p=0.038), community groups (p=0.022), community resource centres (p<0.001), cultural activities (p=0.007), income assistance (p=0.008), mental health services (p=0.034), and recreational activities (p=0.034).

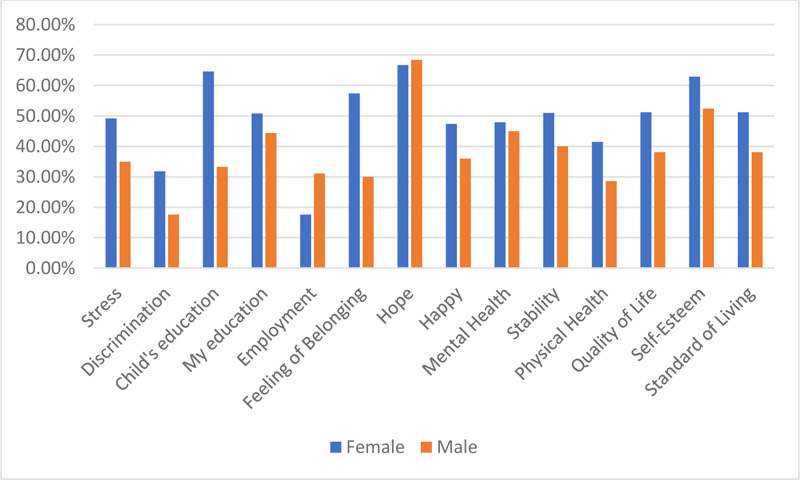

Overall, 80% (59.8-91.5%) of men respondents and 85.2% (78.1-90.3%) of women respondents said they had experienced a positive change in at least one domain since moving into affordable housing (Fig. 2) (domains included: self-esteem, hope, education for self or for child, employment, safety, standard of living, feelings of belonging, stress, physical health, mental health, and quality of life). No statistical difference was seen between genders for any domains.

| - | Female | Male | Significance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time spent in Current Housing | Less than 1 year | 13 (9.7%, 5.7-16.1%) | 3 (12.5%, 4.1-32.6%) | p=0.672 |

| 1-2 years | 17 (12.7%, 8.0-19.5%) | 5 (20.8%, 8.9-41.5%) | ||

| 2-5 years | 41 (30.6%, 23.3-39.0%) | 7 (29.2%, 14.5-50.0%) | ||

| 5+ years | 63 (47.0%, 38.7-55.5%) | 9 (37.5%, 20.7-58.0%) | ||

| Length of Time Expected in Affordable Housing | Less than 1 year | 5 (4.1%, 1.7-9.6%) | 1 (4.8%, 0.7-27.5%) | p=0.618 |

| 1-2 years | 19 (15.7%, 10.2-23.4%) | 1 (4.8%, 0.7-27.5%) | ||

| 2-5 years | 32 (26.4%, 19.3-35.1%) | 6 (28.6%, 13.3-51.0%) | ||

| 5+ years | 65 (53.7%, 44.7-62.5%) | 13 (61.9%, 40.1-79.8%) | ||

| Expectations for Housing in Next 2 years | In Affordable Housing | 87 (70.2%, 61.5-77.6%) | 12 (63.2%, 40.1-81.4%) | p=0.757 |

| In Market Housing (Rented) | 24 (19.4%, 13.3-27.3%) | 4 (21.1%, 8.1-44.8%) | ||

| In Market Housing (Owned) | 13 (10.5%, 6.2-17.3%) | 3 (15.8%, 5.1-39.4%) | ||

3.2. Domestic Violence

Overall, 37.0% of women (95%CI: 28.5-45.5%) and 22.7% of men (95%CI: 4.7-40.8%) reported having experienced domestic violence (p=0.195). Women were more likely to report that domestic violence was a factor in moving into affordable housing (p=0.019). In fact, no men reported that domestic violence was a factor in moving their family into affordable housing compared 31.0% of women (95% CI: 20.9-41.0%). This is likely due in part to the small sample size of men in our study but also highlights the increased likelihood of victimization for women, especially those living in poverty.

3.3. Options for Moving Forward

We found no significant differences between genders regarding the length of time that participants had spent in their current housing (Table 5). Approximately 10% of participants had lived in their housing unit for less than 1 year. Conversely, 47.0% of women and 37.5% of men had lived in their AH unit for five years or more. Over two-thirds of participants expected to live in affordable housing for the next two years and over half of the participants expected to live in affordable housing for the next five years or more, indicating a lack of movement into market housing.

4. DISCUSSION

This small quantitative research study is one of few in Canada to examine demographic characteristics and experiences in affordable housing. Women in our study reported lower education levels and were more likely to be unemployed than men. These findings support other researchers' arguments whereby, women report exacerbated barriers to gainful employment and a living wage [34] and that women are disproportionately represented in low income statistics [35]. We also found that women living in AH were more likely to have children, to be single parents, and to see childcare as a barrier to employment. With the additional burden of childcare placed on women, women may require substantial support for themselves and their families if they are to change their trajectories. The findings regarding childcare are similar to other studies, which found that childcare was a unique need for women [36, 37] and that the burden of childcare largely still sits with women [38].

This study found that 37% of the women participants reported having experienced domestic violence. Women in this study were more likely to report that domestic violence was a factor in moving into affordable housing, whereas none of the men reported this to be the case. This could be due to higher overall rates of violence against women than men, men having many barriers to reporting domestic violence due to gendered norms [39] or could simply be because fewer men were involved in the study. The impacts and effects of DV are trauma related mental health issues like post-traumatic stress disorder and suicidal ideation [40, 41]. Several studies have also shown a strong relationship between DV and homelessness for women in particular [42-44].

As previously argued, competition for affordable housing is a systemic barrier specifically for women experiencing homelessness [45]. This is relevant to the current research since affordable housing and homelessness both exist on the housing continuum and women can experience both and often transition back and forth several times in their lives [46].

Men and women did not differ in the types of housing they lived in before their current housing and approximately 33% of participants came to affordable housing from homelessness. Living with unstable or precarious housing has a similar impact as living in homelessness, including high rates of chronic physical and mental health issues [47]. Other researchers have argued that the experience of homelessness exacerbates the trauma that many women have already faced and that homelessness itself is a form of trauma [48].

Women in our study tended to stay longer in affordable housing units than men and almost half reported living in AH for five years or longer, with half reporting an expectation of a need for AH long-term (an additional five years). This result is particularly troubling given results from previous studies that argue that AH creates dependency and a ‘poverty trap’ and that children and youth living in AH have poor outcomes and are at high risk of repeated or intergenerational poverty and dependency. Participants also reported varying experiences accessing services and supports in their communities.

While more women in the current research tended to report a positive change in at least one domain of living since moving into affordable housing, and a large majority of both women and men reported this to be the case (85.2% and 80% respectively), reported differences in education levels and access to employment, the presence of children and different reasons for the need for AH (e.g., experiences of violence) are gendered differences that must be addressed. These differences highlight the additional struggles that women face when aiming to move out of affordable housing and into market housing. These differences are inequities and are occurring because they are women.

The ‘gender gap’, or structural differences in employment participation and poverty appear among most industrialized countries. However, Sweden and the Netherlands have been able to close the gap on poverty [49]. Generous government transfers and supports designed specifically for women to gain employment were shown to positively impact women’s economic security. Some researchers have argued that if labour force participation rates were comparable to those in countries like Sweden, the gender poverty ratio would be reduced by as much as 60% [50]. This means we can effectively eliminate the feminization of poverty if responses are rooted in the gendered differences that women face. The result is not just a ‘good’ outcome for women, but supports to promote labour force participation, improve overall economic growth and positively impact the outcomes for children, effectively reducing and preventing intergenerational dependency [51].

Gendered differences necessitate gendered responses. This means that women in AH should have barrier free access to education and employment training. These supports must be offered in conjunction with low or no cost childcare. This requires funding from varying levels of government and inter- departmental collaboration since employment and education supports often fall within different ministries or government departments than those for childcare. Given the high rates of women with reported DV and homelessness, supports to heal from trauma must also be offered. Ensuring that AH providers themselves are funded to provide these services will increase the likelihood that women can access them and would reduce the likelihood that women would ‘slip though the cracks’ during a referral process.

4.1. Limitations

While this study adds to the Canadian affordable housing literature, it has several limitations that require acknowledgement. This study had a small sample size which may limit its representativeness of the larger affordable housing environment. In our recruitment, the majority of our participants were women, limiting our statistical power to determine with certainty differences between groups and to analyze this data using more robust modelling.

We were also limited in our report on gender diversity. No one in our questionnaire reported their identity to be other than male or female. This limits our findings in that we are unable to speak to these groups’ experiences. However, future research should embed the need for representation from men and non-binary participants in recruitment strategies.

Limitations with self reported data include participant bias and differences in interpretation of the meaning of the questions. While the research team did meet in person with several participants, several also participated through the online option.

There is a need for more qualitative research to complement existing quantitative knowledge to better understand the nuances and unique experiences of this population. Including a focus on race and culture and the ways in which these identities intersect with gender should be a primary focus of future studies. Women from equity seeking groups face compounding issues, including stigma, racism and discrimination and are more likely to live in poverty [52].

Finally, data in this study were collected before the COVID-19 pandemic. Given the studies that argue that in times of a public health crisis, poverty and dependency levels rise [53], a retrospective study of the impact of the global pandemic on both poverty and its implications could highlight important health, social and economic inequities that are exacerbated by public health emergencies.

CONCLUSION

Recognizing and outlining how the experiences of affordable housing are shaped by one’s gender is an important addition to the public health literature. The current study can inform future policy and decision-making around trajectories into, supports while inhabiting, and trajectories out of affordable housing. Canada’s housing market is competitive and having affordable housing options for those who need it is imperative for safety and stabilization but access to AH without gender appropriate supports to break cycles of trauma and poverty and effectively support lone parent women into sustainable employment with a living wage will likely not lead to accessible market housing. Given the ‘mixed’ results on the positive impacts of AH alone, supported by our study, AH should be viewed as an important first step into stable housing and a critical intervention point for services and supports to heal from trauma and build skills to improve labor force participation for women. These should not be implemented without access to low or no cost child care. AH in and of itself is not a panacea and should not be viewed as the long term outcome, rather, our goal should be to close the gender poverty gap so women can be empowered to create and sustain their own economic security and ensure brighter futures for themselves and their children.

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

Ethics approval for this project was received from the University of Calgary’s Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board (REB 17-0816).

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

IRISS (Institutional Research Information Services Solution) is an online system that manages all human ethics and animal care protocols for the University of Calgary. No animals were used in this study. All human research procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the committee responsible for human experimentation (institutional and national), and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2013.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

All participants provided signed informed consent.

STANDARDS OF REPORTING

STROBE guidelines and methodologies were followed in this study.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

The study data and materials are not publicly available due to the confidentiality and privacy of the participants.

FUNDING

Based within the University of Calgary, make Calgary is a multi-faculty collective that supports research-based exploration of the links between municipal policies, urban planning/design/architecture, equity, and public health. Make. Calgary provided a research grant and supported opportunities for knowledge exchange for this project. Grant number: 2017-MC02.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest financial or otherwise.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the staff and residents of the affordable housing units where we collected data. Without their collaboration and support, this project would not have been possible.