All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Social Environment as a Precursor to Coronary Artery Disease in a Small, Resource-Limited Country

Abstract

Background:

Coronary artery disease has been the most prevalent chronic disease over the last two decades. In Trinidad and Tobago—a small, high-income, resource-limited country the median age of presentation of, and premature death from, acute myocardial infarction is more than 12 years earlier to that in high-income, developed countries. This may be attributed to the increased risk of coronary artery disease that stem from the presence of precursors in the social environment.

Objective:

We aimed to explore the association between “social environment” and coronary artery disease in Trinidad and Tobago.

Methods:

This is a descriptive ecological study that assessed secondary data. Data were collected from multiple search engines and websites. Data on Trinidad and Tobago’s social environment were also accessed from the World Databank and the Central Intelligence Agency fact book and analyzed.

Results:

Coronary artery disease was fueled by personal choices that were influenced by the social environment (“fast food” outlets, inadequate sporting facilities, increased use of activity-saving tools [vehicles, phones, and online activities], smoking and alcohol accessibility, and social stressors [murder, family disputes, divorce, child abuse, kidnapping, and rape]). Food imports, as a percentage of merchandise imports, were at 11.42% (2015); the level of physical activity was low (<600 MET-minutes per week; 38 in 2016), and social stressors were high.

Conclusion:

The social environment has encouraged a “cardiotoxic” or “atherogenic” environment influencing behavior, eventually resulting in a continued high risk of coronary artery disease, presenting at a younger age.

1. INTRODUCTION

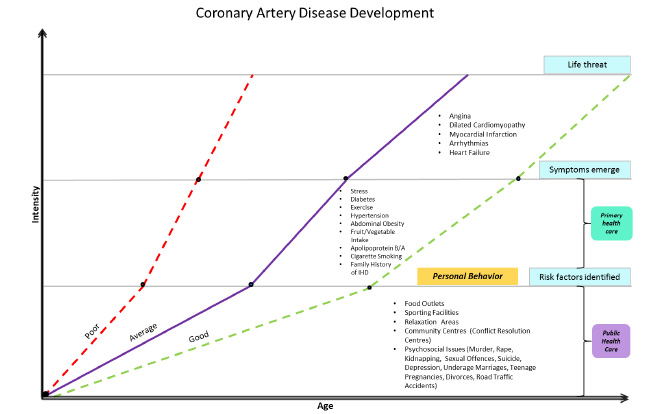

Coronary artery disease (CAD), like aging, is inevitable. However, CAD is accelerated by a multitude of risk factors, both modifiable and non-modifiable. Genetic engineering [1] that aims to minimize CAD risk is still in the early stages and is unlikely to achieve the desired targets. Much of the current research efforts have aimed to identify, modify, and treat cardiovascular (CV) risks [2] at an individual level. This was emphasized by Levenson et al., who reported that to reduce the impact of the global explosion in CV diseases (CVDs), it is important to understand and reduce the global increase in CVD risk [3]. CV risk development varies according to genetic transmission, individual behavior, and the social environment [4]. Trinidad and Tobago’s financial investment and health interventions have focused mainly on the individual’s responsibility to decrease the prevalence and improve or control CV risks. Interventions, such as the “Fight the Fat campaign,” “avoiding sweets,” and “exercising”, are commonly echoed in educational forums to change behaviors and decrease CV risk [5]. This practice of individual responsibility continues despite the recommendation of Trinidad and Tobago’s National Strategic Plan for non-communicable diseases [6], which requires that individuals take advantage of an enabling environment to control, improve, and maintain physical, mental, social, and spiritual well-being. Social determinants as a cause of CAD have been described by Kreatsoulas and Anand [2], Albus [7], and Bhatnagar [4]. These social determinants or environmental public health issues are the “root causes” that contribute to an atherogenic environment and the resultant increase in CAD risk and CAD [7] (Fig. 1).

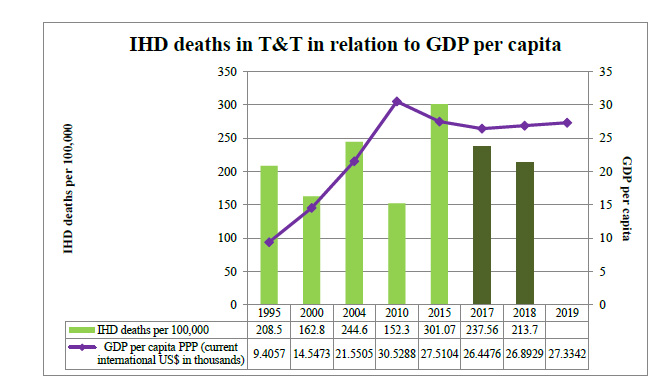

In societies where geographic, environmental, and other socioeconomic problems are scarce [8], there is a lower chance of the early development of CAD; for example, in France, with its excellent public health system, there is a high life expectancy and low CVD mortality rate. In Trinidad and Tobago, with its high incidence of ischemic heart disease (IHD) and CAD, the main causes of death over the previous two decades (Fig. 2), the young age of presentation and premature death resulting from acute myocardial infarction (AMI) [9] have led to IHD being a major cause of concern. This study explores the social environment and its role in CAD development in a small, resource-limited country.

IHD, ischemic heart disease; T&T, Trinidad and Tobago; GDP, gross domestic product; PPP, purchasing power parity.

Data retrieved from “The ministry of health. (2016). Healthgovtt. Retrieved 10 August, 2016, from http://www.health.gov.tt/downloads/DownloadItem.aspx?id=33” and “Healthdataorg. (2017). Healthdataorg. Retrieved 10 July, 2017, from http://www.healthdata.org/trinidad-and-tobago”

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

This is a descriptive ecological study. This study analyzes secondary data from 1990 to 2021, comparing local data with two first-world countries, namely the USA and the UK. Data were obtained using various search engines: Google, PubMed, EBSCOHOST, and the websites of the Pan American and World Health Organizations. Data (published and unpublished) were also obtained from the Ministry of Health, World Databank, and the Central Intelligence Agency fact book websites. Local statistical data were obtained from the Ministry of Health and the Central Statistical Office of Trinidad and Tobago.

Search terms, such as “infrastructure,” “social determinants,” “CVD,” “CAD,” and “society”, were used. Local data included information on national health indicators, CAD risks, and environmental public health or social environment. CAD risks included diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, smoking, alcohol use, and psychosocial factors. Environmental public health precursors [4], such as food outlets, sporting facilities, and social determinants, were identified in the local context. Research assistants assisted in data collection.

We analyzed CAD risks and the social environment to determine any links between them. The results are presented as graphs and tables. Due to limited resources and lack of funding, data collection was mainly confined to the local context. Nevertheless, the collected data were useful for understanding the associations likely existing between environmental public health issues and CAD risks.

3. RESULTS

The prevalence of abdominal obesity (48.1% in 2016) and diabetes mellitus (12.5% in 2016) in Trinidad and Tobago was much higher than that in the UK and the USA (Table 1). However, the prevalence of hypertension (45% in 2018) was higher in the USA than in Trinidad and Tobago. The prevalence of CV lifestyle risk factors (insufficient vegetable intake, sedentary activity) and psychological risks (stress) was higher in Trinidad and Tobago than in the USA and UK. Smoking prevalence (approximately 14% in 2019) in Trinidad and Tobago was similar to that in developed countries, like the USA and the UK.

3.1. Social Environment

The social environment influences our behavior: “Where to go? What to eat? Should I exercise? How to utilize spare time? How can social conflict be dealt with?” In this study, there was observed a remarkable increase in the social environmental factors (non-activity-related pastimes/sedentary activities, fast food outlets, smoking and alcohol outlets, and social stressors). Fast food outlets per million population have increased from 119 in 2012 to 142 in 2017, with the food import bill as a percentage of merchandise imports increasing from 8.31 in 2000 to 11.42 in 2015 [34]. The increase in the use of electronic devices (cell phones, vehicles) and the decrease in the number of playgrounds have also encouraged a sedentary lifestyle. Social stressors are high and are increasing. Generally, the rates of stress, depression, unemployment, murder, rape, divorce, suicide, traffic congestion, and road traffic deaths have fluctuated over the last decade; however, they remain high. The unemployment rate has also fluctuated (an average of 18.52% in 1991 and a decrease to 6.7% in 2020) [35]. Over the years, there has been a high level of murders (396, or 28.2 per 100 000, in 2020) [36] with low detection levels (lower than 26%). There has also been a high prevalence of teenage pregnancies, child marriage, divorce, abortions, incest, family conflicts, income discrepancies/inequity, major life events, and job losses (Table 2).

| Risk Factor | Measure of Risk Factor | Prevalence by Year |

UK Values % |

USA Values % |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1990 | 2000 | 2005 | 2010 | 2015 | 2020 | 2016-2020 | 2016–2020 | ||

| Cigarette smoking | Smoking prevalence in the adult population (%) [10] | n.a. | 11.67 | 12.94 | 14.45 | 14.04 (2016) | n.a. | 14.1 (2019) [11] | 14 (2019) [12] |

| Hypertension | Hypertension (% adult population) | n.a. | n.a. | 30.4 (2008) [13] | 27 (2011) [14] | 28 (2016) [15] | n.a. | 26.2 (2017) [16] |

45 (2018) [17] |

| Diabetes | (% of population aged 20–79 years) | n.a. | 12.7 (2001) [18] | n.a. | 11.7 [19] | 12.5 (2016) [20] |

11.0 (2019) [19] | 7 (2020) [21] |

5.2 (2020) [22] |

| Abdominal obesity | Overweight/obesity (share of adults [%]) [23] | 25.90 | 33.60 | 37.60 | 42.00 | 47.10 | 48.10 (2016) | 28.0 (2019) [24] | 42.4 (2017–2018) [25] |

| Lack of daily consumption of fruits and vegetables and fat consumption |

Fruit consumption per capita (kg/year) [26] | 57.15 | 64.81 | 73.63 | 75.68 | 111.85 (2013) |

50.91 (2017) |

89.60 (2017) | 90.00 (2017) |

| Vegetable consumption per capita (kg/year) [27] | 20.99 | 31.90 | 35.82 | 30.26 | 35.68 | 36.09 (2017) | 82.91 (2017) | 113.41 (2017) |

|

| Daily per capita dietary fat supply (grams per person per day) [28] | n.a. | n.a. | 79.33 | 82.30 | 89.93 (2016) | 88.93 (2017) | 141.03 (2017) | 167.21 (2017) | |

| Lack of daily exercise | Low level of physical activity (<600 MET-minutes per week) | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 45.4 (2011) [13] | 38 (2016) [15] | n.a. | 25 (2017–2018) [29] |

>15 (2020) [30] |

| Family history of IHD | - | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| Excess use of alcohol | Share of population with an alcohol disorder (%) [31] | n.a. | 1.57 | 1.65 | 1.73 | 1.73 | 1.72 (2017) | 8.7 (2016) [32] | 5.8% (2020) [33] |

| Social and Psychosocial Factors | Year | US | UK | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1990 | 2000 | 2005 | 2010 | 2015 | 2020 | (2017–2021) | (2017–2021) | ||

| Major fast food outlets (n) [37] (per million population) | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 118.6 (2012) | n.a. | 142 (2017) | 599.8 (2021) [38] |

>386.9 (2018) [39] | |

| Food imports (% of merchandise imports) [40] | 15.427 (1991) | 8.313 | 9.02 | 11.19 | 11.42 | n.a. | 15 (2019) [41] |

9.1549 (2019) [42] |

|

| Daily per capita dietary fat supply (grams per person per day) [43] | 65.00 | 76.32 | 79.33 | 82.30 | 92.50 | n.a. | 167.21 (2017) |

141.03 (2017) | |

| Vehicles registered, per 1000 [44] | n.a. | n.a. | 351.0 | 361.0 | 397.0 | 1016.26 (2017) [45] | 838.7 (2019) [46], [47] |

487.19 (2019) [48], [49] | |

| Internet users (% of the population) [50] | 0 | 7.721 | 28.977 | 48.5 | 69.198 | 77.326 (2017) | (>85%) (2020) [51] | 92.517% (2019) [52] | |

| Mobile cellular subscriptions (per 100) [53] | 0 | 12.774 | 71.276 | 142.623 | 154.954 | 155.109 (2019) | 134.459 (2019) [54] | 119.898 (2019) [55] | |

| Unemployment rate (% of the working population) [56] | 18.52 (1991) | 12.1 | 7.9 | 5.9 | 3.4 | 6.7 | 5.9 (2021) [57] |

4.8 (2021) [58] | |

| Pupils attaining tertiary education (%) [59] | 6.615 (1991) | 6.061 | 11.951 (2004) | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 19.6 million (2019) [60] | 2.38 million (2018/ 2019) [61] | |

| Murder (per million people) [62] | 102.1 (1994) | 84.3 | 275.7 | 346.4 | 292.9 | 282.9 | 58.1 (2019) [63] | 10.7 (2019/2020) [64] | |

| Rape (per million people) [65] | n.a. | 186.4 | 238.6 | 155 | 128.6 | 65.7 (2019) [66] |

98213 (2019) [67] | 62200 (2019/2020) [68] | |

| Kidnapping (per million people) [69] | n.a. | n.a. | 41.4 [62] | 80 (2013) |

75.7 | 46.4 | n.a. | 85.1 (2020/2021) [70] |

|

| Sexual offences (per million people) [71] | n.a. | 202.9 | 288.6 | 343.6 | 495 (2014) | >394.3 (2019) [66] |

1393.9 (2019) (rape and sexual assault) [72] | >2663.7 (2019/2020) [73] | |

| Suicide rate per 100,000 [74] | n.a. | 16.3 | 12.7 | 11.3 | 10.2 | 8.7 (2019) | 16.1 (2019) [75] | 7.9 (2019) [75] | |

| Depression (%) [76, 77] | 2.97 | 3.38 | 3.49 | 3.56 | 3.57 | 3.57 (2017) | 4.84% (2017) [78] |

3.96% (2017) [79] |

|

| Underage marriages (per million people) [80] | n.a. | n.a. | 49.3 (2006) | 49.3 | 7.1 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | |

| Teenage pregnancies (per million people) [81] | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 532.1 | 269.3 (2018) | n.a. | 760.3 (2018) [82] | |

| Divorces (per million people) [83] | n.a. | n.a. | 1798.6 | 2087.1 | 2010 | n.a | 2267 (2020) [84] | 1752 (2019) [85] | |

| Road traffic deaths (per million people) [86] | n.a. | n.a. | 134.3 (2006) | 129.3 (2011) | 146 | 96 | 36096 (2019) [87] |

1752 (2020) [88] | |

4. DISCUSSION

This study reveals the continued high prevalence of CV risk. The main thrust of the Ministry of Health was to change the individual’s effort/behavior (the “ability to change deeply entrenched habits and accept personal responsibility for our health status” [6]) and the presence of supportive public health regulations. The public health measures are as follows:

(i) The Tobacco Control Act (which banned smoking in public spaces and prohibited the promotion and sale of tobacco products to children)

(ii) The Tobacco Control Regulations, 2013

(iii) The National Policy on Alcohol

(iv) Breathalyzer legislation (to prevent drunk driving)

(v) Campaigns targeting healthy eating and active living (2008 to present)

(vi) The National School Health Policy

(vii) Health Promotion Policy for Public Sector Agencies in the Workplace

(viii) The Fight the Fat Campaign, 2012–2014 [6]

However, public health laws on smoking, alcohol use, and calorie documentation are seldom adhered to [89]. This also applies to many other regulations (littering, child protection, speeding, and seat belt regulations) [90]. This has created an environment where there is a lack of enforcement of public health regulations and a focus on individual’s efforts, thereby leading to a largely uncontrolled “social environment.” There has been observed a higher prevalence of diabetes mellitus and obesity in Trinidad and Tobago than in the USA and the UK, which may have resulted from the social environment with its abundance of fast food outlets, sedentary lifestyle activities/jobs, and social stressors. Apart from the increase in food consumption, our food content has revealed high levels of sugar, saturated fats, and carbohydrates, and there is a growing use of alcoholic beverages and low fruit and vegetable intake [91], encouraging the development of atherosclerosis [92].

The social environment with high traffic density, and the use of mobile phones and the internet, have encouraged a sedentary lifestyle. Vehicular traffic was high and ranked 41st in the world in 2007 [93]. The 2019 traffic survey results revealed that the citizens of Trinidad and Tobago spent at least 2-3 hours per day in traffic, resulting in lower work productivity levels, while stress affected family life [94] and increased the risk of CVDs [4]. The high incidence of crime and violence has further limited the use of the outdoor sporting facilities and leisure parks. Physically active people have an improved quality of life and a reduced risk of premature death [95]. Physical activities have shown improvements with the use of environmental designs in terms of modes of transportation (bicycles and cars) [96] and individuals’ choices to exercise [97].

The prevalence of social stressors in Trinidad and Tobago is high. However, the high levels of depression (3.57% in 2017) [98], suicide (8.7 per 100,000 population in 2019) [99], and divorce (2814 in 2015) [83] are not unique to this country. In the UK, the occurrence of depression (3.96% in 2017) [100], suicide (7.9 per 100,000 population in 2019) [101], and divorce (108,421 in 2019) [102] is comparable. Depression [103], anxiety, anger, hostility, acute and chronic life stressors [104], downward social mobility [105, 106], and lack of social capital [107, 108] are associated with risks of CVDs. Alcohol abuse as a social stressor also results in associated road traffic accidents, domestic violence, and medical problems [109]. With two-thirds of households consuming alcohol, the sequelae of psychological, physical, and social problems contribute to coronary artery plaque build-up [110].

This study has some limitations and “epistemic gaps” [111, 112]. It has used mainly secondary data, most of which could not be independently verified. Because of the limitations in time and resources, it did not include data on either socioeconomic status or the “exposome” (e.g., noise and chemical pollutants, [113, 114]), which are all implicated in the development of CAD.

CONCLUSION

The social environment (eating places, playing fields, and psychosocial stressors), a precursor to CAD, may be responsible for the continued high levels of CAD risk and CAD, young age of AMI presentation, and AMI death. Further studies are required to elucidate the type and degree of influence on behavior.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| AMI | = Acute Myocardial Infarction |

| CAD | = Coronary Artery Disease |

| CV | = Cardiovascular |

| CVD | = Cardiovascular Disease |

| IHD | = Ischemic Heart Disease |

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

MB designed the study, collected and supervised the data collection, and wrote and edited the manuscript.

AUTHOR INFORMATION

MB is a specialist medical officer and part-time lecturer at the University of the West Indies (Mount Hope, Trinidad and Tobago).

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

Not applicable.

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

Not applicable.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

The data supporting the findings of the article are available from the corresponding author [M.B] upon request.

FUNDING

None.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The author declares that there are no competing interests.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author would like to thank the premedical students Esther Ramlackhan and Alexia Mahadeo, who assisted in the data collection.