All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Perceptions and Experiences of Males who have Sex with Men Regarding Sexual and Reproductive Health Services in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe

Abstract

Background:

Sexual and Reproductive Health services are a cornerstone for each nation to achieve Sustainable Development Goal Number 3, which challenges nations to ensure healthy lives and promote the well-being of all ages, including access to SRH services. Generally, stigma and policies against men who have sex with men have heightened the risk of getting and spreading sexually transmitted diseases in this key population. This study, therefore, sought to explore men who have sex with men's perceptions and experiences of sexual and reproductive health services offered in Bulawayo in Zimbabwe.

Methods:

An exploratory, descriptive qualitative study was conducted on twenty-four (24) purposively selected men who had sex with men identified through Sexual Rights Centre in Bulawayo. The study participants responded to unstructured interview questions that probed on their lived experiences and perceptions of sexual and reproductive health services offered by health facilities in the city of Bulawayo. The interviews were recorded, transcribed verbatim, coded, and thematically analyzed on MAXQDA Version 20 Pro.

Results:

Findings suggested that men who had sex with men sought a wider range of sexual and reproductive health services that ranged from voluntary counseling and testing, treatment of sexually transmitted infections, and obtaining pre-exposure prophylaxis tablets, among other issues. However, men who had sex with men faced discrimination, stigma, and hostile treatment by some health service providers. This scenario, in some instances, is perceived to have fueled their vulnerability and led to internalized homophobia.

Conclusion:

In pursuit of Sustainable Development Goal Number 3, which challenges all nations to ensure healthy lives and promote well-being at all ages, men who have sex with men are not fully accorded their rights. Therefore, there is a need to reorient health services and align policies to ensure the inclusion of this key population in accessing and utilizing sexual and reproductive health services.

1. BACKGROUND

Sexual and Reproductive Health (SRH) services are a cornerstone for each nation to succeed in moving toward the attainment of Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) Number 3, which challenges nations to ensure healthy lives and promote the well-being of all ages, including access to SRH services [1, 2]. Therefore, it is enshrined in most countries' constitutions that every citizen has a right to access health care services, including decent SRH services, regardless of social and economic status [3]. The global burden of Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs) is very high, with an incidence estimated at 769.85 million worldwide in 2019, thus calling for realistic and effective interventions that would reduce the cost on different aspects of social and economic fronts [4]. Most countries have called for a reorientation of the health systems to be as inclusive, accommodating and integrated as possible to ensure access to SRH services that foster safe sexual practices [5, 6].

Issues of Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights (SRHR) are a matter of urgency deserving meticulous attention by all stakeholders [7-9]. SRHR entails sexual pleasure, safe sexual living, and the right to decide when and how to have children [7, 10]. The minimum package of SRHR services is anticipated to, among others, include comprehensive sexuality education, counseling on SRHR, interventions to prevent and/or respond to sexual and gender-based violence and coercion, effective methods for contraception, safe and effective abortion services, prevention, diagnosis and treatment of Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs) including Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), safe antenatal, maternal and postnatal care and male circumcision [8, 10].

Globally, men who have sex with men (MSM) experience prejudice, stigma, discrimination and differential treatment within the SRH system [11]. It has also been reported that the prevalence of STIs (including Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV)) is high in this key population as they shun hostile health care service providers [12, 13]. Gay and bisexual men have additional challenges compared to the general population because of factors related to the social determinants of health: social, political, economic, and healthcare-related [14]. This amplifies existing health inequities, including mental health challenges [14]. Negative attitudes about same-sex relations can harm gay and bisexual men's health, leading to internalized homophobia that often catalyzes and interacts with other areas of their lives where they experience discrimination [15]. Depending on the country or context in which they live, stigma and discriminatory consequences of racism, tribalism, economic inequities, and belonging to a sexual minority can cause adverse health outcomes [15]. Sixty-nine countries criminalize consensual same-sex sexual behavior between consenting adults. Some countries, such as Iran, even permit the death penalty for those convicted of engaging in same-sex acts [16].

In Zimbabwe, MSM are stigmatized, and the policies put in place do not fully recognize their rights leading to the majority shunning health services meant to improve their sexual health outcomes [17]. They are usually called unacceptable names that are derogatory and directly attack their sexual orientation [17, 18]. Generally, MSM are left behind in programs meant to improve their sexual health outcomes and contribute to SDG Goal 3. In Bulawayo, there is a lack of critical and contextualized information on experiences and perceptions of MSM and their needs such that programmers consider these and inform policies so that they are as inclusive as possible. Against this backdrop, this study sought to explore men who have sex with men's perceptions and experiences of sexual and reproductive health services offered in Bulawayo in Zimbabwe.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Study Area

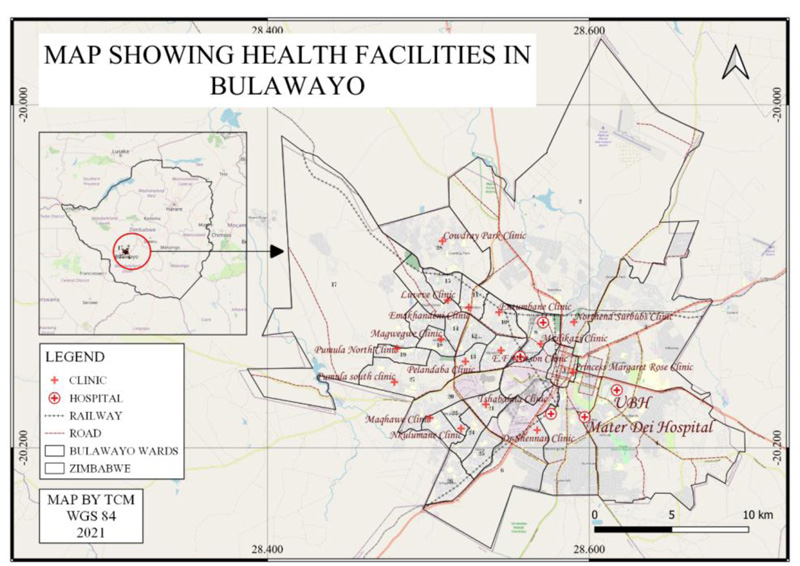

The study was conducted on MSM as captured on the Sexual Right Centre's clientele. Bulawayo is the second capital city in Zimbabwe and has an estimated population of 640 000 in 2021 based on the 2012 censures and the population growth rate of 1.56 per annum [5, 19]. The city is serviced by private and public health facilities, with most of these facilities being public and owned by the government. The city has many clinics run by the Ministry of Health and Child Care (sometimes in collaborative efforts with Non-Governmental Organizations and Donors) and three referral health facilities that is, United Bulawayo hospitals, Mpilo Central Hospital and a mental institution Ingutsheni Hospital. The private sector also runs several health facilities in the city. The map of the study area is presented in Fig. (1).

2.2. Study Design

An exploratory, descriptive qualitative study was conducted on selected participants and probed their lived experiences. This study design was appropriate as it enabled the researchers to get in-depth information about the participants' lived experiences and how these subsequently shaped their perceptions about access to SRH services in Bulawayo [20, 21]. The innermost beliefs and deliberations based on their lived experiences paint a clearer picture of how specific issues of concern are perceived [20]. Therefore, this study design enabled an in-depth understanding of the services available for MSM and their experiences and perceptions of these services [22, 23].

2.3. Study Population and Sampling

The study targeted MSM in the Sexual Rights Centre databases and came out about their sexual orientation and preferences. The participants were purposively selected to participate in the study, and the total number of participants required was determined by data saturation. One of the key inclusion criteria was that the MSM had visited health facilities searching for SRH services within the last 12 months before this research was conducted. The participants were sensitized first before participating in the study. These participants were the youth registered with the Sexual Rights Centre and within the age range of 18-35 and had come out in the open about their sexual orientation.

2.4. Data Collection and Tools

The study participants responded to piloted unstructured interview questions (Face to Face) that probed on their experiences and perceptions of sexual and reproductive health services in Bulawayo. The interviews were guided using an interview guide that enabled the collection of relevant data through the inquiry of lived experiences and the exploration of the participant's perceptions of the services offered and received in the health facilities. The interviews were recorded using a tape recorder after the participants gave consent before recording. The interviews took between 20 and 40 minutes to administer by the authors in a place of choice by participants where they felt comfortable. Researchers ensured that only the participant was present to ensure confidentiality and a conducive and free environment. The interviews were conducted in English, isiNdebele or Shona (depending on the participants' preferences), as these are the three major languages spoken in Zimbabwe.

2.5. Data Management and Analysis

The recorded data were transcribed verbatim, and the transcripts were exported to MAXQDA Version 20 Pro (software used for qualitative data coding and theme development) for coding and thematic analysis. Thematic analysis is a method for analyzing qualitative data and entails searching across a data set to identify, analyze, and report repeated patterns of specific phenomena [24]. It is a method for describing data but also involves interpretation in selecting codes and constructing themes [24]. Two independent coders coded the data. Superordinate and subordinate themes were identified for presentation to answer the study's objectives.

3. RESULTS

The participants' ages ranged from 18 to 35 years. They reported that there are either in gay relationships or are engaged in bisexual relations where they have sex with both men and women. These demographic characteristics are presented in Table 1.

| Respondent # | Age | Sexual Orientation | Education Level | Employment Status | Marital Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P-01 | 28 | Gay | Gay Hons Degree Employed In a same-sex relationship | Employed | In same-sex Relationship |

| P-02 | 28 | Bisexual | Hons Degree | Employed | Single |

| P-03 | 35 | Bisexual | Post Grad | Employed | In a relationship |

| P-04 | 33 | Bisexual | Post Grad | Freelancer | Married to a female partner |

| P-05 | 24 | Bisexual | Undergrad Student | Student | In a relationship with female and male partners |

| P-06 | 31 | Gay | National Certificate | Intern | Single |

| P-07 | 33 | Gay | Master of Philosophy | Employed | Engaged |

| P-08 | 35 | Gay | O level | Self-employed | In a same-sex relationship |

| P-09 | 30 | Gay | Hons Degree | Volunteer | Single |

| P-10 | 27 | Gay | 2 Post Grads | Employed | In a same-sex relationship |

| P-11 | 26 | Gay | Diploma | Employed | In a same-sex relationship |

| P-12 | 24 | Bisexual | O level | Unemployed | In a relationship with a man and a woman |

| P-13 | 27 | Bisexual | Diploma | Employed | In a relationship with a woman |

| P-14 | 33 | Gay | O level | Unemployed | In a same-sex relationship |

| P-15 | 26 | Gay | O level | Volunteer | In a same-sex relationship |

| P-16 | 33 | Gay | O level | Self-employed | In a same-sex relationship |

| P-17 | 26 | Bisexual | O level | Employed | Married to a woman. |

| P-18 | 21 | Gay | O level | College student | In a same-sex relationship |

| P-19 | 18 | Bisexual | O level | College Student | In a same-sex relationship |

| P-20 | 29 | Gay | Hons Degree | Employed | In a same-sex relationship |

| P-21 | 22 | Gay | A level | Undergrad Student | In a same-sex relationship |

| P-22 | 31 | Bisexual | Hons Degree | Employed | Single |

| P-23 | 23 | Bisexual | College Diploma | Unemployed | Single |

| P-24 | 21 | Bisexual | O level | College student | In a same sex relationship |

| Themes | Subthemes |

|---|---|

| Experiences of men who have sex with men in accessing SRH services. |

Types of services sought and needs Types of services sought and needs Access to services Access to services Positive experiences when looking for these services Positive experiences when looking for these services Challenges experienced in accessing the services Challenges experienced in accessing the services |

| Perceptions of gay and bisexual men regarding SRH services in Bulawayo |

Understanding of SRHR services Understanding of SRHR services Acceptability and accessibility of the services Acceptability and accessibility of the services Health care worker’s attitudes toward MSM Health care worker’s attitudes toward MSM Health System Bureaucracies Health System Bureaucracies Discrimination Discrimination Internalized homophobia Internalized homophobia |

3.1. Emerging Themes

Ten subordinate themes emerged under the two superordinate themes (Experiences of men who have sex with men in accessing SRH services; Perceptions of gay and bisexual men regarding SRH services in Bulawayo). These themes are summarized in Table 2 and will be discussed in detail in this section.

3.1.1. Experiences of Men who have Sex with Men in Accessing SRH Services

A total of four subordinate themes arose from this superordinate theme. Participants detailed their experiences regarding access and utilization of SRH services across the city. These subordinate themes are described in detail in the subsections that follow:

3.1.1.1. Types of Services Sought and Needs

Participants cited several SRH services that they sought from health facilities. It emerged those services such as access to Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP), voluntary counseling and testing. Participants cited that they have varied needs since they have anal sex. These ranged from seeking information about different conditions and understanding how the health service providers could assist and exploring the available options of SRH services. The participants

Participants said:

“…unprotected sex, and you are not sure of your partners, status, but also because there's now been the rollout of services such as prep…. So, when you meet someone, and someone suggests that they like you, the reality is you might just want to please them and have sex with them in the anticipation that you will probably have a relationship. Still, for our LGBT community, it's always different because people want to pass each other around and have a taste of what's new. So, the safest measure I could have is probably to take PrEP just in case I get into a situation where I sleep with someone without using protection”.(P-01).

“… I went to test, and there is pre and post-test counselling services that are offered …” (P-08).

“Okay, so I think the first thing probably has accessible sexual reproductive health resources. For example, let's say condoms. Even when I want to check my prostate, if I want to go and even get maybe checked because, you know, sometimes, many things happen. Sometimes you can have piles, but you don't know exactly what this is. And because primarily, we do have anal sex. You get that fear. So, I think we must have a comprehensive package where people can go without fear of getting anything checked. Be it's the one to access even circumcision or things like that it's important for it's to be done in a space where a person is comfortable. Right now, yes, we do know that they offer mobile services and everything, but I'll never be comfortable enough just to tell them that I want to get circumcised they come to my house and, or they just come in, they say to get into the kind, let's do this and things like that, I will need to have a space where it is friendly, where people can access services”. (P-17).

3.1.1.2. Access to Services

Participants cited that their rights were sometimes being violated as they are given negative attitudes once they declare that they have sex with other men. It also emerged that this situation was improved by providing dedicated clinics for the LGBTIQ+ community, which were sensitive to their needs. Participants further cited that their privacy is sometimes infringed on, which then influences them from not utilizing the services as their issues are discussed by the health service providers in front of their family members, particularly for those that are bisexual. It also emerged that the service they sometimes get is rushed as many health service providers are not comfortable with MSM and would generally want to dismiss them as soon as possible.

Participants said:

“Okay, um, that's a tough one because our rights practically have always been violated because of maybe constitutionalism. And if it wasn't for the fact that we now have specific places where we go to that have been sensitized, I think that right now, it would still be difficult for the ordinary, gay or bisexual men to access services”.(P-01).

“Let's take, for example, bisexual men, and them probably going, and maybe let's say that in accessing services, maybe with their wives and everything, and then one day, they go to that particular place where they accessed services, and they've got maybe anal watts. It would be a terrifying experience because the clinicians would ask. Still, we've always seen you with your wife; how do you have anal watts, so the experience will probably be uncomfortable and challenging”. (P-04).

“So, it's just like, I remember there was a time when we went as mystery clients to a health facility. When we got there, well, the nurse wasn't bad. But then there were some other services I thought she just did in a hurry. I didn't get the worth of that service. For example, we were two, and when we got there, she took our blood samples; we were in the same room, and there was no privacy. When the results were out, there were just announced, and I got to know my friend's results, and he saw mine. I felt shortchanged and not satisfied with the quality of service. And for that, that would ring a red light for me not to go back to that institution because there is no privacy in itself”.(P-05).

3.1.1.3. Positive Experiences when Looking for these Services

Participants cited that some health facilities and organizations have been sensitized and treated with respect and dignity, thus encouraging more MSM to visit those specific welcoming and sensitive health facilities. Participants further elaborated that despite the availability of these services, there are still difficulties that they face:

One participant said:

“If it wasn't for the fact that we now have specific places where we go to, that have been sensitized, I think that right now, it would still be difficult for the ordinary, gay or bisexual men to access services.”(P-13).

3.1.1.4. Challenges Experienced in Accessing the Services

Participants cited that most health care workers ill-treat them and have an attitude toward them. It emerged that MSM is usually discriminated against with harsh words being said to their faces, including demonizing them. Participants further cited that their constitutional rights have always been violated, exacerbated by the attitudes that most service providers have toward MSM and usually treat them in manners that do not uphold their dignity. Participants further elaborated that because they prefer to go to the same health facilities for continuity, there is always a likelihood of being judged or confronted; for example, if someone is bisexual and has presented with a wife at some point at the facility, it becomes a challenge to now bring a male partner to the same health facility. Participants also cited that most health facilities are not inclusive; therefore, they have preferences of a few facilities that have been sensitized thus raising concerns transport costs as some would be far from their residential areas.

Participants said:

“My first experience there was really bad because obviously, they are questions asked during post counseling such as being asked about your partner history, your sexual life history, and I thought that I was in a safe space and there was going to be no judgment I mentioned that I was gay. The responses were amazing in a negative way because the health service provider blatantly said, “you know that these are demons, right, and you are aware that probably your parents didn't pray hard enough”. (P-07).

“Okay, um, well, that's a tough one, because our rights practically have always been violated because of maybe constitutionalism.”(P-12).

Let's take, for example, a bisexual man, and them probably going, and maybe let's say that in accessing services, maybe with their wives and everything, and then one day, they go to that particular place where they access and they've got maybe anal watts; obviously, it would be a terrifying experience, because the clinicians would ask no, but we've always seen you with your wife, how do you have anal watts, so the experience is probably going to be it would have always been challenging”. (P-13).

“I have preferences of facilities to go to, for example, and those run under Population Services International (PSI). But in the real world, that would have been inclusive. Sometimes it's tough, and when I stay in Thorngrove to go all the way to town, I can simply go to Mpilo or Mzilikazi clinic, which is near but because Mzilikazi clinic right now has been sensitized. They know us and things like that. I would prefer to go to a place that's accessible where I don't need to run away from my community. And when accesses are far because I'm afraid, because yeah, so I would want that”.(P-14).

3.1.2. Perceptions of Gay and Bisexual Men Regarding SRH Services in Bulawayo

Six superordinate themes emerged from this superordinate theme. These are summarized in Table 2 and are discussed in detail in the following subsections.

3.1.2.1. Understanding of SRH Services

Participants knew it was within their rights to have access to SRH services, and they understood that access to these services enables them to have better health outcomes. Participants further cited that it is the responsibility of health service providers to enable them access to these services and ensure that their health outcomes are improved. It also emerged that participants are aware of the SRH services there are supposed to get from the health facilities though sometimes their expectations are not met. Participants further highlighted that they would need facilities to be as inclusive as possible to feel comfortable acquiring those services. They felt that they should be reading materials and pamphlets in the waiting rooms that also address issues on MSM so that they feel included.

One participant said:

“Okay. So, for example, if I walk into a hospital, I need to see posters that also show inclusiveness, a poster with a rainbow flag, and any other flag that's part of the LGBTI. And even pamphlets that are there, all the desks that even if I'm waiting for my service, I can still be reading about things that concern me specifically. Because when we look at even back in the day, it was always part of the binary narrative, that is always going to be signage, and it's the woman's name, all the information is based on the man and woman. But for me, I cannot consume that material because I don't relate to it. So, I would need those things also to be part of that experience. So that even if I want to take a home a pamphlet or take it even to my friends that are also afraid to go, I can easily show them that this place is inclusive”.(P-01).

3.1.2.2. Acceptability and Accessibility of the Services

Participants perceived the services as acceptable due to the awareness campaigns done at the community level to aid inclusion. Participants hinted that though some have not sought the services of late, they have a general feeling that there has been an improvement due to intensive awareness campaigns and sensitization of health service providers in specific health facilities to ensure they have a supportive environment to deal with the needs of MSM.

One participant said:

“Okay, I think access right now is improved. And there have been drastic changes, which have also been mostly community-led”.(P-21).

3.1.2.3. Health Care Workers' Attitudes toward MSM

Participants highlighted that most health service providers in health facilities that were not sensitized to deliver services to the LGBTIQ+ community were very hostile and judgmental to MSM. Participants also highlighted that they felt generally shortchanged as most of the services offered are rushed and dismissed without getting the quality they think they deserved. However, some were unsure what they should expect from the health facilities.

Participants said:

“It's not been an easy road; I don't want to lie. I remember there was a time when I went to Population Services International because they had been rolling out the MSM program, which is the minimum Sex with Men program. I already thought it would be a safe space for me to even interact with counselors and share my experiences in terms of my sexual life. But I was grossly disappointed by the first time I went to test, and in as much, as there's always been the narrative that that particular counselor is old fashioned and doesn't want to understand and will also be asleep probe questions in the not most palatable way”.(P-01).

“…The responses were amazing in a negative way because she blatantly just said that you know that these are demons, right. And you are aware that probably your parents didn't pray hard enough”. (P-07).

3.1.2.4. Health System Bureaucracies

Participants felt that the systems, particularly in public institutions, do not have standardized procedures or services that are inclusive and cater for MSM needs.

One participant said:

“The services offered in institutions are not generalized; some institutions are friendly and sensitized to MSM while some have judgmental and hostile staff members that would call you all sorts of names.”(P-05).

3.1.2.5. Discrimination

Participants expressed their opinions that they felt they were not being treated the same as those in heterosexual relationships. Participants cited that they generally feel discriminated especially when they disclose that they are either gay or bisexual, while seeking health services.

One participant said:

“So we see poor seeking behaviors, we also experience quite a lot of self-stigma, self-stigma, especially when it related to sexual related health problems, STIs, you know, somebody feels so shy to come open and say I have an STI and I want treatment, intimate partner violence, we men are still finding it very difficult to open up in-depth discussions around that, especially for men who are in same-sex sexual relationships, the violence is very high, but we were do not talk about It.”(P-04).

3.1.2.6. Internalized Homophobia

Participants explained that they are sometimes treated in a manner that could affect the mental status of the MSM seeking help. Participants cited that how they are treated could lead to some of the MSM hating themselves or having low self-esteem due to the treatment and disheartening words they receive from the judgmental health service providers. Therefore, the participants felt or perceived this to be one of the key drivers that could lead to low self-esteem and internalized homophobia.

Participants said:

“And, to hear someone like that saying something like that, it's probably disheartening. Because probably, maybe I'm a tough person. And you can imagine the number of people that have gone through that same counselor each day, and being told things like that, and how it can help, like affect their mental health”.(P-01).

“…In one approach, there is a lot of stigma and discrimination, especially its public service providers who have not been sensitized on LGBTI and sex worker issues. This results in low self-esteem among the MSM and self-hate”.(P-10).

4. DISCUSSION

Generally, it emerged that the services that MSM was seeking were slightly different from those sought by those individuals in heterosexual relationships. It emerged that similar services were sought that included getting access to condoms, PrEP, HIV and AIDS counseling and testing over and above. MSM will seek access to curative services if they have conditions associated with anal sex. Generally, the demand for sexual and reproductive health services is reported to be lower than that of heterosexuals [25]. The study further reported that some participants reported that they explored the available options that were available for them in health facilities. It is reported that same-sex couples normally have the worst sexual health outcomes as the available services in health facilities are not tailored in a way that is meant to respond to their unique needs (and they are not standardized to offer consistent services). They are more often than not comprehensive enough to respond to the needs of individuals who are in same-sex relationships [26].

The study further revealed that though the SRH services are available for them to utilize, there were sometimes inaccessible as they were given attitudes and called all sorts of degrading names because of their sexual orientation. In Zimbabwe, policies and legislative frameworks do not recognize same-sex relationships. This scenario has created an environment where the sexual rights of different populations under the LGBTIQ+ umbrella are violated [26]. The absence of policies that regulate or promote the inclusion of these key populations in the planning and implementation of SRH services has created a vacuum where the needs and access to specific services by the MSM have been neglected. This creates a scenario where their demands or needs are not met as the services are not tailored in a way that aids their inclusion. It is critical that services are tailored to be as inclusive as possible if acceptable sexual health outcomes are to be realized, including in MSM [27-29].

It also emerged that some positive outcomes or experiences were reported by the participants in pursuing sexual health services in different facilities they visited. They reported that visiting facilities that work with Non-Governmental Organizations meant to promote access to sexual health services by the LGBTQI+ populations were sensitized and treated with dignity and respect. This scenario facilitated SRH services and encouraged the MSM to seek and enjoy the available services in a comfortable environment. It is reported in the literature that health services seekers that are treated with respect and dignity are usually satisfied with the services that would have been provided to them, thus creating more demand for those specific services in those specific facilities, thus translating to improved sexual health outcomes [30-32]. It further emerged that even though these dedicated facilities have been sensitized, there were still some challenges in accessing the services as the right attitudes by the health service providers toward MSM have not been fully attained. This is consistent with other findings in different studies that show that change is a process and does not manifest overnight; thus, there is a need for the change process to be given more time and awareness campaigns consistently done [33, 34].

This study showed that some health service providers have a negative attitude toward MSM, thus ill-treating and discriminating against the MSM who would be seeking SRH services in some health facilities. It also emerged that some health facilities are friendly to MSM. This scenario leads to the MSM seeking services in those specific health facilities even though some are far from their areas of residence, leading to increased expenditure on transport. It has been reported that distance from health facilities is also a factor that influences health-seeking negatively [30, 35]. This generally leads the MSM to seek services late when there are already some complications, fearing being victimized and stigmatized in areas where they stay [11, 12]. It is reported that stigmatization has led to attacks on MSM in some parts of the world [14]. The study's findings also show that the way health service providers treat MSM could lead to internalized homophobia where MSM may feel less worth and hate themselves, thus predisposing them to mental instabilities that might lead to them committing suicide or falling into depression. Studies suggest that self-hate can lead to low self-esteem and thus hinder those affected from living socially fulfilling lives, thus increasing the probability of those affected committing suicide [36-38].

5. STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY

The study focused on participants in the urban setup of Bulawayo. They had ties or relations with the Sexual Rights Centre and came out about their sexuality. This could have led to those that had not disclosed being left out and their voices not being heard. Therefore, the participants who participated in this study had already made their sexuality preferences known, had been sensitized generally about their rights and were readily available to share their experiences with the health systems in seeking SRH services.

CONCLUSION

From the findings of this study, it can be concluded that the absence of inclusive policies has made MSM vulnerable as far as SRH outcomes are concerned. The attitudes reported as being exhibited by some health service providers discouraged those seeking SRH services and thus reduced the demand for those services. This scenario also led to participants having preferences in the health facilities they utilized, particularly those sensitized to be inclusive. Therefore, inclusive policies must be crafted such that the services offered to MSM are standardized regardless of the facility one visits. These policies should be crafted to promote inclusivity and ensure that those in need of SRH services have access without hindrances to improve their sexual health outcomes. There is also a need to train health service providers on providing conducive environments that would aid access and acceptability of services rendered to MSM.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| LGBTQI | = Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, Intersex |

| HIV | = Human Immunodeficiency Virus |

| MSM | = Men who have sex with men |

| PrEP | = Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis |

| SRH | = Sexual and Reproductive Health |

| SRHR | = Sexual and Reproductive Health Rights |

| STIs | = Sexually Transmitted Infections |

AUTHORS' CONTRIBUTIONS

TM conceptualized the research idea as a BSc dissertation topic. The author designed the methodology and data collection tools and collected and conducted the initial analysis of the data. WNN was the supervisor who played a major role in refining, guiding the student, and drafting the actual manuscript. WNN drafted the manuscript and performed a thematic analysis (on MAXQDA Pro Version 20) to corroborate the initial analysis performed by TM. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

This study was approved by the Department of Environmental Science and Health at the National University of Science Technology, Zimbawe.

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

No animals were used that are the basis of this study.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

An information sheet detailing the purpose of the study was availed to the participant before seeking consent for their participation. Written consent was sought from the participants.

STANDARDS OF REPORTING

STROBE guidelines were followed.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIAL

The data supporting the finding of this study are available within the article.

FUNDING

The research was funded fully by the Sexual Rights Centre in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.

DISCLOSURE

TM is a Policy and Advocacy Manager at the Sexual Rights Centre in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe. The author was also a BSc in Environmental Science and Health Student in the Department of Environmental Science and Health at the National University of Science and Technology in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe. WNN is an Associate Professor in the Department of Environmental Science and Health at the National University of Science and Technology in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe and holds a PhD in Public Health. Both researchers were male.