All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

The Status of Integrating Children and Adolescents’ Mental Health Care Services into Primary Health Care in South Africa: Scoping Review

Abstract

Background:

Many children and adolescents who need mental health care services in South Africa find it difficult to access these services. The PHC approach is the foremost strategy adopted by the South African government to improve access to health care services in the country. Therefore, the integration of children and adolescents mental health care services into primary health care should greatly improve access.

Objective:

The objective of this review is to describe and interrogate the status of integrating children and adolescents’ mental health care services into primary health care in SA.

Methods:

The scoping literature review was conducted following the framework of identifying the research question, identifying relevant studies, selecting studies, charting data, and finally collating, summarising, and synthesising the results. The databases used are APA, PsychINFO, Medline, Cabinet Discover, and Africa-Wide Informatio. Thematic analysis was used to qualitatively analyse the findings of the studies reviewed.

Results:

Six studies were selected for inclusion in this research. The analysis yielded three themes : challenges to integrating child and adolescent mental health care, services into primary health care, the need for health care systems to enable integration of child and adolescent mental health services into primary health care, and the lack of child and adolescent mental health care services.

Conclusion:

The integration of child and adolescent mental health care services into primary health care in South Africa is far from realisation. Recommendations are made for practice, education, and research.

1. INTRODUCTION

Adolescence is the most challenging period in human life. Apart from physiological changes, adolescents undergo psychological and social metamorphosis. Adolescents start developing an interest in the opposite sex, need to establish independence, and their relationships with peers become more important and intense [1, 2]. These changes contribute to the susceptibility of adolescents to peer pressure and various challenges such as substance use and/or abuse, unplanned pregnancy, and risky behaviour [3, 4]. These challenges, in turn, increase the risk of mental disorders among adolescents.

A national survey in 2017 in England found that at least one in eight children and adolescents aged 5 to 19 years had one mental disorder, while one in 20 had two mental disorders [5]. Sadler et al. [5] further indicate that the most common mental disorders in these age groups of 5 to 19 years were emotional in the form of depression, mania, anxiety, and bipolar. These disorders were more common in girls than in boys. The disorders listed here were followed by disorders characterised by violent behaviour, such as conduct and defiant disorders, which were more common in boys than girls [5].

Schizophrenia, anxiety disorders, bipolar, and depression are some of the conditions found among adolescents in the Danish study [6]. According to Thorup et al. [6], the main attribute that makes these adolescents susceptible to such mental disorders is genetics. In Norway, it was found that children and adolescents aged between 7 and 13 years had one or more neurodevelopmental disorders, with attention deficit hyperactivity as the most common, followed by tic disorder and autism spectrum disorder [7].

Although it is common knowledge that neurodevelopmental disorder commences in infancy, the literature indicates that mental disorders usually have their onset at an early age. As much as 50% of mental disorders commonly afflict children and adolescents have onset by 14 years, and 75% manifest by 24 years [8]. Fusar-Poli et al. [8] further state that mental disorders could be detected by 11 years of age among individuals who are diagnosed by the age of 26 years. Sadler et al. [5] point out that children as young as 2 to 4 years of age have been found to have a mental illness, but those aged 17 to 19 years were three times more likely to have a mental disorder than those aged 2 to 4 years.

It is evident that children and adolescents suffer from mental disorders at a very early age, yet there is a delay in intervention. Initiation of treatment for a child or adolescent with an anxiety disorder has been shown to delay for 9 to 23 years [8]. On the other hand, the delay in initiating treatment for those with mood disorders is 6 to 8 years [8]. This delay was established in a study conducted in England. Sadler et al. [5] indicate that only two-thirds of 5 to 19-year-olds in England had access to professional services, and only 25.2% of them through a mental health specialist. These authors further explain that one in five children and adolescents with mental disorders had to wait more than six months to access a mental health specialist [5]. This indicates that many children and adolescents do not have access to mental healthcare services.

Most research on child and adolescent mental healthcare services seems to be done mostly in developed countries, and the discussion thus far paints a gloomy global picture of child and adolescent mental healthcare. This generates a rationale to explore how South African (SA) experiences could be mapped and described. One can only expect it to be worse due to various problems in the country. The monitoring of mental health, especially among children and adolescents, is currently very poor, resulting in the scarcity of recent statistics [9]. The South African Stress and Health (SASH) study, a national survey conducted in 2009, indicated 30.3% of the lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in SA. The study indicated that among 4351 respondents, 11% had two or more mental disorders, and about 3.5% had three or more of these disorders [10]. The most common were anxiety disorders, with a 15.8% prevalence, followed by substance use disorders at 13.3% and mood disorders at 9.8% [10]. This prevalence is for adults aged 18 years and above. Nonetheless, it highlights two important things: the first is that the trend of mental disorders in SA is similar to the global trend, and the second is that, given the fact that the majority of mental disorders (75%) onset by the age of 24 years, almost similar statistics could be expected among adolescents in SA. Furthermore, it is important to note the serious gap in the literature on mental health problems among children and adolescents, except for one study conducted in the Western Cape province published in 2006, which indicates that 17% of children in that province have a diagnosable mental disorder [11]. The dearth of recent literature on the extent of mental disorders underscores the need to focus on child and adolescent mental health.

This also brings us to the question of mental healthcare services for children and adolescents in SA. Some studies in SA have emphasised that mental healthcare services for children and adolescents in SA are lagging. Hunt et al. [12] show impaired access to mental healthcare services for this at-risk population by indicating that 6.8% of inpatients and 5.8% of outpatients were people below the age of 18 years. The same authors further clarify that only three of nine South African provinces had a child psychiatrist in the public health sector [12]. Sorsdahl et al. [9] also posit that South African adolescents have under-utilized mental healthcare services.

Can this poor access to mental healthcare services among children and adolescents be improved by integrating mental healthcare into primary healthcare (PHC)? Petersen et al. [13] argue that integrating mental health in the PHC could improve access to mental healthcare. This is the main aim of this paper. The integration of mental healthcare into the PHC has been introduced by the World Health Organisation (WHO) as far back as 1994 [14]. Since then, numerous scholars have argued for integrating mental healthcare into the PHC [15, 16].

Children and adolescents have poor access to mental healthcare services, yet, they are the most vulnerable population to mental disorders [9]. Furthermore, mental disorders and utilisation of mental healthcare services among children and adolescents do not seem well-monitored and recorded in SA [12]. Integrating mental health into PHC is one possible solution to counter all these challenges [17]. This scoping review, therefore, seeks to explore and describe the status of integrating children and adolescents’ mental healthcare services into PHC in SA.

2. METHODS

Given the shortcomings in children and adolescent mental health challenges in SA, the researchers deemed scoping review the most suitable type of study for this research. The scoping review examines the depth, range, degree, and landscape of research activity on a specific topic [18, 19]. It also identifies gaps in the literature, collates, summarises, and disseminates research findings, making these accessible to researchers in the field [20, 21]. Furthermore, it does not necessarily call for a quality assessment of available literature [20], making it favourable when one should include other documents such as policies and guidelines, which may also help in unearthing the available information that should bridge what is missing in the body of knowledge pertaining a specific phenomenon. The scoping review was therefore seen as the most suitable type of study because it allowed the reviewers to examine the intent and nature of the research on integrating child and adolescent mental healthcare services into the PHC in SA. Knowing this extent should assist in summarising the available knowledge and guiding the focus of future researchers, critiquing and suggesting robust research methods that may have the desired impact on children and adolescent mental healthcare projects.

The commonly used framework in conducting scoping reviews are the five stages outlined by Arksey and O’Malley [19], which are 1) identifying the research question, 2) identifying relevant studies, 3) study selection, 4) charting the data, and finally 5) collating, summarising and reporting the results. These five stages are followed in this review and act as the framework for this review.

2.1. Research Question

The question that guided this scoping review was: what is the status of integrating children and adolescents’ mental healthcare services into PHC in South Africa?

This question was addressed through secondary questions as follows:

What are the challenges of integrating children and adolescents’ mental healthcare services into PHC in SA?

To what extent are child and adolescent mental healthcare services integrated into PHC in SA?

2.2. Identifying Relevant Literature

The databases used in this scoping review are APA PsychINFO, Medline, Sabinet Discover, and Africa-Wide Information. These databases are relevant to mental health and coverage of various research, especially those published in Africa and South Africa. The time frame for the search was from 1994 to 2022 to ensure broad coverage of studies and policies relevant to the research question. In this article, adolescence refers to a stage in one’s life characterized by a sequence of hormonally induced physiological, social, and psychological growth and development which bring emotional and behavioural changes starting in the early teen years to the early 20s and adolescence suggests any person aged from 12 to 20 years while a child is a person aged younger than 18 years. Children and adolescent mental healthcare services are defined as those establishments and personnel aimed at assessing, treating, and rehabilitating persons aged 20 years or younger who experience behavioural, emotional, psychological, or any other mental health problems. The term primary healthcare refers to healthcare services that are accessible across the clock, geographically and financially, for all persons and communities, and PHC facilities refer to PHC clinics that operate eight or 12 hours a day and community health centres that operate 24 hours a day.

The keywords used were ‘mental health, ‘integration,’ ‘primary healthcare,’ and ‘South Africa.’ Synonyms such as the ‘Republic of South Africa’ for ‘South Africa’ were also utilised in the search. The keywords “children and adolescents” were not used to widen the search because some articles covered child and adolescent mental health without including them in the title. Nonetheless, the reviewers used “children,” “adolescents,” and synonyms like “teenagers” and “young adults” in the final stages of assessing the full texts to ensure that the target population was selected. The search was guided by the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The reviewers used a Boolean search strategy using the operators “And” and “OR.” The operator “NOT” was not used, and the setting on fields was set at “all fields” because the reviewers did not want to limit the search in any way. The combination of terms was mental health OR mental health services And integration AND South Africa OR the Republic of South Africa. In addition to this search, the reviewers set the field to “abstract” and repeated the search to make the search more comprehensive.

2.3. Study Selection

The selection of the studies included was based on the following criteria.

Inclusion criteria

The articles were published from 1994 to 2022,

The article should include “children and adolescents” as its population or one of its populations or focus on or cover children and adolescent mental healthcare;

The articles were published in English and focused on South Africa as its context.

2.4. Exclusion Criteria

Articles that focused on integrating mental healthcare into the PHC but did not cover “children and adolescent mental healthcare” were not included.

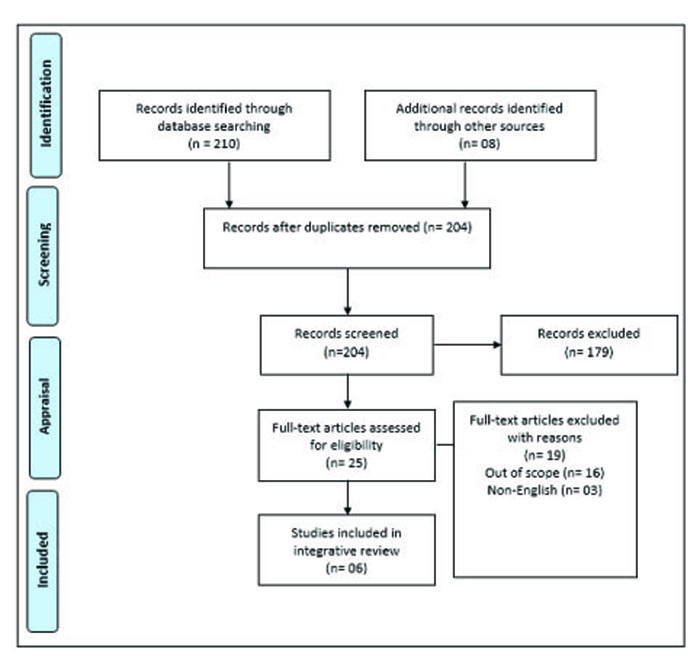

The search of the four databases yielded 210 articles, and the bibliography search of the six included studies yielded eight articles, all of which were already found in the search of the databases. After a screening of all articles, only six satisfied the inclusion criteria. The selection process of the articles is summarised in Fig. (1).

2.5. Data Extraction

The data extraction was conducted independently by two reviewers. The two reviewers reviewed one article together to ensure consistency, then reviewed the remaining five independently. The two reviewers then met to discuss the extractions and identify discrepancies until they reached a consensus. The extracted data was then checked against the six sources by all reviewers.

2.6. Data Analysis

The data was analysed using thematic data analysis. The reviewers first read through the six articles to be familiar with the sources and then generated codes by labelling different notable information from the six articles. Then the reviewers developed themes by assessing the generated codes to look for similarities and overlaps. Then decided which needed to be combined/ grouped and named these different themes bearing in mind the review question, aim and objectives. The themes were reviewed, then defined and named to finalise the themes.

3. RESULTS

This scoping literature review sought to describe the status of integrating child and adolescent mental healthcare services in the PHC in South Africa. The screening process included six studies, the analysis of which yielded three themes and sub-themes.

3.1. Charting Data

Six studies were included in this scoping review. Most studies are mixed-method research studies, and most use mental healthcare practitioners as participants or as part of the target population. The studies covering child and adolescent mental healthcare services in the PHC were conducted only in three out of nine provinces, and most were carried out in the Kwa-Zulu Natal province. It is important to note that the researchers in the current study did not find any studies that focused specifically on integrating child and adolescent mental health care services into PHC. However, some studies in SAf focus on integrating mental health into the PHC, with a minute number covering child and adolescent mental healthcare. The studies that were included in this review are summarised in Table 1. The two studies were mixed methods, two were qualitative, and the remaining two were situational analysis and a report paper, respectively. Four of the studies used the stakeholders as a target population. Some described which stakeholders were involved and indicated that the stakeholders were mental health practitioners, PHC practitioners, teachers, non-profit organisations and officials from the department of health and basic education. It is important to note that none of the six studies has adolescents as participants, and all five articles used adults, without specifying their age, as participants.

| Study | Design | Population & Context | Data collection | Data analysis | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gerber (2018), Practitioners’ experiences of the integration of mental health into primary healthcare in the West Rand district, South Africa [18] | Mixed method exploratory descriptive | PHC practitioners, Gauteng province | Structured questionnaire & Semi-structured individual interviews |

Mixed method analysis | The lack of child mental health resources in the PHC is one of the challenges identified (139) |

| 2. Babatunde, Bhana and Petersen (2020), Planning for child and adolescent mental health interventions in a rural district of South Africa: A situational analysis [22] | Situational analysis | Stakeholders (psychiatrists, psychiatric nurses, medical officers, sychologists, social workers, operational managers, and community volunteers) and hospital records, Kwa-Zulu Natal province | Semi-structured interviews and situational analysis tool | Excel, descriptive statistics for quantitative data, framework analysis for qualitative data | There are no specialists for children and adolescent mental health services. The lack of task-sharing mechanisms due to the lack of specialists decreases access to CAMH. There is a need to expand CAMH specialists and ensure a functional system of care. The CAMH services are not provided in the PHC facilities due to a lack of training and supervision. 49 -52). |

| 3. Lund et al. (2011) Challenges facing South Africa’s mental healthcare system: Stakeholders’ perceptions of causes and potential solutions [23] | Qualitative study | Stakeholders (healthcare professionals, teachers, police officers, academics, religious and traditional leaders., Kwa-Zulu Natal province | Individual interviews with 99 participants and 14 focus group discussions | Framework analysis | There is a need for a national mental health policy that covers different populations, including children and adolescents. |

| 4. Petersen et al. (2009) Planning for district mental health services in South Africa: A situational analysis of a rural district site [24] | Mixed methods | Stakeholders, Kwa-Zulu Natal province | WHO-AIMS for quantitative data, semi-structured interviews and focus group discussions | Simple descriptive statistics for quantitative and framework analysis for qualitative data. | There are no specialised services for children and adolescent mental health services. Children were only referred for disruptive behaviour and as a result of abuse. |

| 5. Franz et al. (2018) Providing early detection and early intervention for autism spectrum disorder in South Africa: Stakeholder perspective from the Western Cape province [25] | Qualitative study | Stakeholders from departments of health, social development, education, and non-profit organisations. Western Cape province | Semi-structured individual interviews | Content analysis | Integrating mental healthcare for children into existing systems of care is necessary. |

| 6. Kleintjies et al. (2021) strengthened the national health insurance bill for mental health needs a response from the Psychological Society of South Africa [26] | Report paper | Not applicable | Not applicable | Not applicable | The funding for children and adolescent mental health services should be prioritised. |

3.2. Collating, Summarising, and Reporting the Results

Three themes emerged from the thematic analysis of the included studies: challenges to integrating children and adolescent mental health into PHC, the need for healthcare systems to enable integration of children and adolescent mental healthcare into the PHC, and the lack of child and adolescent mental healthcare services. The first and second themes have three subthemes each, while the third has two sub-themes, summarised in Table 2.

| Themes | Sub-themes |

|---|---|

| Challenges to integrating children and adolescent mental health into PHC | Lack of specialists |

| Lack of resources | |

| Lack of training and support for PHC practitioners | |

| The need for healthcare systems to enable the integration of children and adolescents into mental healthcare and the PHC | Need for specialised team for children and adolescent mental health |

| Need for functional healthcare systems | |

| Need for prioritised funding | |

| Lack of children and adolescent mental healthcare services | Lack of specialised mental health services for children and adolescents |

| Poor referral system for children and adolescents with mental disorders |

4. DISCUSSION

The first theme challenges integrating children and adolescent mental healthcare services into the PHC, which alludes to different impediments regarding integrating children and adolescent mental healthcare services into the PHC in SA. As indicated in these studies, the first of these challenges is the lack of child and adolescent mental health specialists. Babatumbe, Bhana and Petersen [22] established that in one rural district, which generally resembles the situation in various rural districts in SA, no mental health specialists were dedicated to children and adolescents. Furthermore, very few specialists had to cater to adults and children, which increased their workload and impeded optimum mental health care for children and adolescents. These impediments complicate the accessibility of mental healthcare services for children and adolescents. This lack of child and adolescent mental health specialists led to a paucity of task-sharing, where a mental health practitioner has to do many therapeutic tasks for the wellbeing of the mental healthcare user alone [22]. This, in turn, contributed to reduced access for children and adolescents to mental healthcare services.

The second sub-theme is the lack of child and adolescent mental healthcare resources. Gerber [17] found that PHC practitioners experienced the non-availability of child and adolescent psychiatric resources and a lack of mental health care users’ records or access to these records. Lack of mental healthcare resources is one of the perennial problems in low and middle-income countries such as SA, which is one of the reasons why integrating mental health into PHC has been advocated for in these countries [27].

The third and last sub-theme blocking integrating children and adolescent mental healthcare services into PHC is the lack of training and support for PHC practitioners [22]. The PHC practitioners indicated they lack competence in delivering child and adolescent mental healthcare services because they are not trained for it. Because they lack robust training, they do not receive sufficient supervision for implementing that [22]. This is further complicated by the lack of children and adolescent mental health specialists because, ideally, these specialists should provide support and supervision to these PHC practitioners.

The second theme concerns health care systems' status to enable the integration of children and adolescent mental healthcare into the PHC. This theme indicates that there are systems that are necessary to enable the integration of children and adolescent mental healthcare services into the PHC.

The first sub-theme is the need for specialised teams for children and adolescent mental health. The mental healthcare practitioners in the Western Cape province of SA indicated the need for a specialised child and adolescent mental health team [22]. They alluded that such a team existed in their context and proved it could effectively provide access to mental healthcare for children and adolescents, but it needed to be expanded [22]. The existence of multi-disciplinary teams in specialised mental healthcare institutions such as psychiatric hospitals attests to the need for such specialised teams for children and adolescents [28]. Furthermore, Ireland established multidisciplinary Community Mental Health Teams in 1984 when they decided that mental healthcare should be provided within communities rather than centralised in psychiatric hospitals [29].

The second sub-theme is the need for functional healthcare systems. Stakeholders from the departments of health, social development and education, as well as those from non-profit organisations, indicated that children and adolescent mental healthcare services should be built into the systems of care that are already in existence and running [25]. An example of existing systems of care included special schools for children with autism spectrum disorders [25]. Arguably, the PHC in SA can also be regarded as one existing and running system of care into which children and adolescent mental healthcare services could be integrated.

The third sub-theme is the need for prioritised funding for children and adolescent mental health. This recommendation is proffered by the Psychological Society of South Africa in line with the anticipated National Health Insurance in SA [26]. The SA national and provincial health departments allocate extremely low amounts of funding towards mental health compared to general hospitals [30].

The third theme is the lack of specialised child and adolescent mental health services, which concerns the fact that no specialised child and adolescent mental healthcare service is provided, even in the many hospitals in SA.

The first sub-theme is the lack of specialised mental healthcare services for children and adolescents. Pertersen et al. [24] conducted a situational analysis of district mental health in a rural district and verified that district did not have specialised services for children and adolescent mental health. This indicates that integrating children and adolescent mental health into the PHC is still quite remote in rural districts, far more than in urban/ developed districts in SA.

The last sub-theme is a poor referral system for adolescents with mental disorders. The systematic review showed that children and adolescents referred for mental healthcare were only those who displayed disruptive behaviour and those who were victims of abuse [24]. The overall picture painted by these results is that child and adolescent mental healthcare services in SA are very poor, and for integration into the PHC to be realised sooner, there should be an immediate and radical change.

In the general view of literature on the integration of children and adolescent mental healthcare services into the PHC, there is still a need for conducting more substantive studies. South African scholars have also indicated the importance of integrating mental healthcare into the country's PHC; others even trialed it. For example, Petersen et al. [13] piloted integrating mental healthcare into chronic disease management in the PHC in the North-West Province (NWP) and found that PHC nurses could identify mental disorders such as depression. In the Kwa-Zulu Natal (KZN) province, a lack of training in mental health for PHC practitioners and inadequate resources impeded the integration of mental health into the PHC [31]. Gerber [17] found that the integration of mental healthcare in Gauteng Province was feasible but had challenges like perceived increased workload and resistance from the PHC practitioners. In the Western Cape, Jacob and Coetzee [32] found that factors that blight the integration of mental health into the PHC were the high burden of disease, stigma, and poor staff training. It is important to note that these studies assessed mainly the integration of mental healthcare into the PHC in general, not specifically for children and adolescents. However, one of the studies suggests that the lack of available child psychiatric resources was a barrier to integrating mental health services into the PHC in Gauteng province [17]. This shows that children and adolescent mental healthcare services in PHC have not received the attention they deserve in SA. This is emphasised by the fact we found only one study focusing on children and adolescent mental healthcare services conducted in SA thus far. This calls for more focus from South African scholars on mental healthcare services for children and adolescents.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the literature that focuses on integrating child and adolescent mental healthcare services into the PHC is limited in the South African context. Scholars have only considered this niche area in three of the nine South African provinces. Nonetheless, this review demonstrates that child and adolescent mental healthcare services in SA are very poor. The review also showed that children and adolescent mental healthcare services have hardly been integrated into the PHC in the context of SA, thereby endorsing the need for immediate measures that could facilitate the integration of children and adolescent mental healthcare services into the PHC in SA. There are a few recommendations derived from the results of this review.

It is recommended that, at the practice level, the PHC practitioners be trained in children and adolescent mental healthcare so that they can provide such service at the PHC level. The Department of Health should send various PHC practitioners, especially professional nurses, for advanced qualifications in child and adolescent mental health, such as child psychiatric nursing, just as they currently send them for advanced midwifery training. The mental health specialists should be allocated weekly visits to the PHC facilities to attend to the PHC clients, including children and adolescents. These specialists should also be allocated at least a day a month to supervise and support PHC practitioners who do not have mental health specialisation in providing mental healthcare to PHC clients, including children and adolescents. A clear and easy-to-follow referral system for adolescents with mental health problems should be developed for PHC practitioners.

Health science education institutions and such nursing education institutions should ensure that children and adolescent mental health are adequately covered during basic training of health professionals so that the healthcare professionals allocated to PHC can provide basic mental healthcare services to various PHC clients, including children and adolescents.

The policy developers and health authorities in the Department of Health should develop PHC-specific policies for integrating mental healthcare services for various populations, including children and adolescents, into the PHC. They should also allocate sufficient funding for developing and providing child and adolescent mental healthcare services in the PHC.

Scholars and researchers across all provinces of SA are urged to conduct more research on child and adolescent mental health, including but not limited to common mental disorders, determinants of healthcare service utilisation, and the ultimate integration of children and adolescent mental healthcare services into the PHC.

LIMITATIONS OF THE STUDY

The study strove to identify and critique articles written in English, which may have led to the exclusion of studies in other languages that archive important information on integrating children and adolescent mental health services into the PHC.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable.

STANDARDS OF REPORTING

PRISMA guidelines and methodology were followed.

FUNDING

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

PRISMA checklist is available as supplementary material on the publisher’s website and the published article.